Abstract

Objectives: A Rapid Realist Review of social prescribing in Higher Education (HE) was undertaken to determine what works, for whom, how, why, and within what circumstances. The review resulted in the development of a Realist Programme Theory articulating the way in which social prescribing can be implemented within the HE environment.

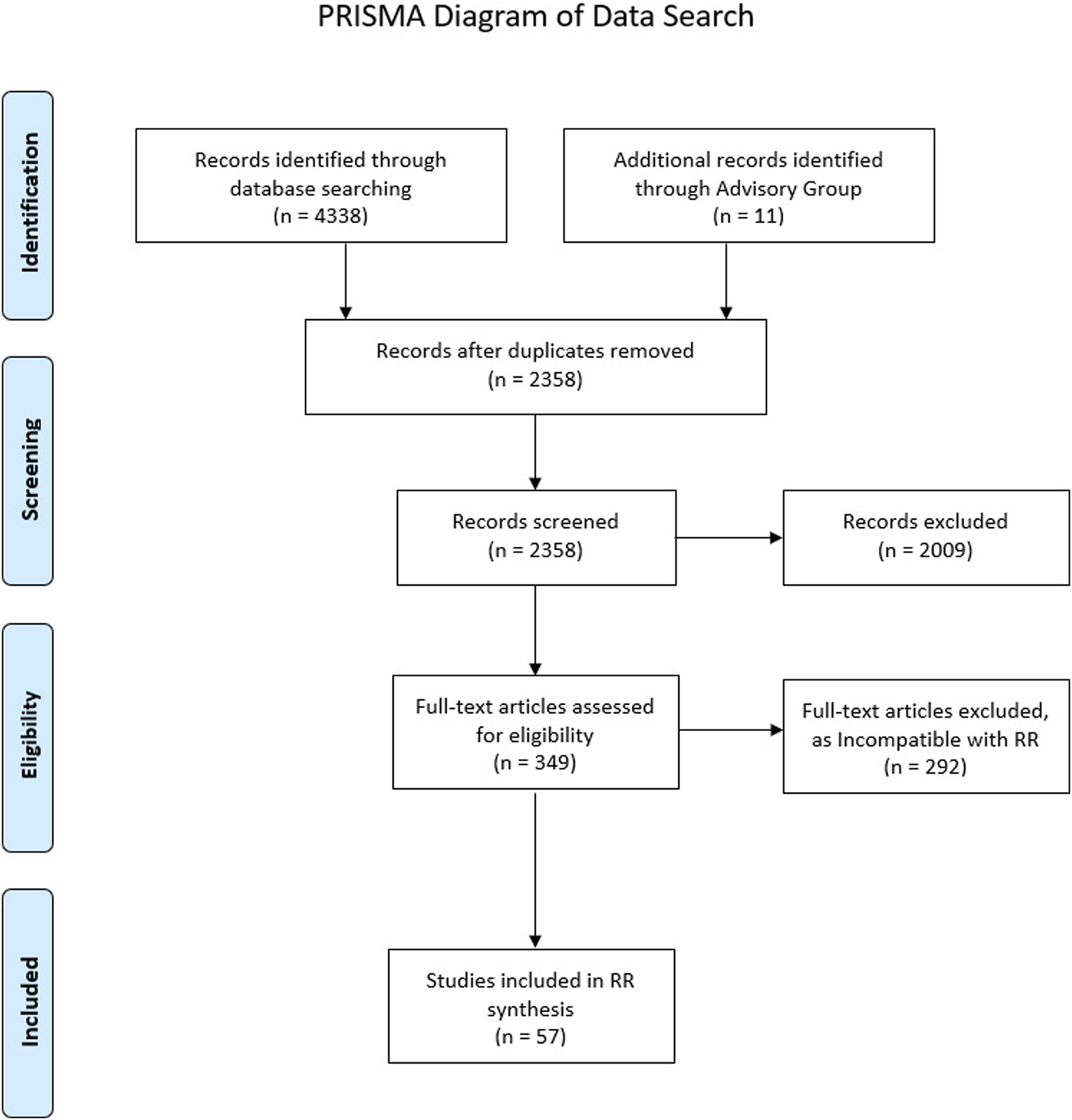

Methods: Searches of 12 electronic databases were supplemented by citation chaining and grey literature surfaced by the Project Advisory Group. The RAMESES Quality Standards for Realist Review were followed, and the retrieved articles were systematically screened and iteratively analysed to develop Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configurations (CMOCs) and an overarching Realist Programme Theory.

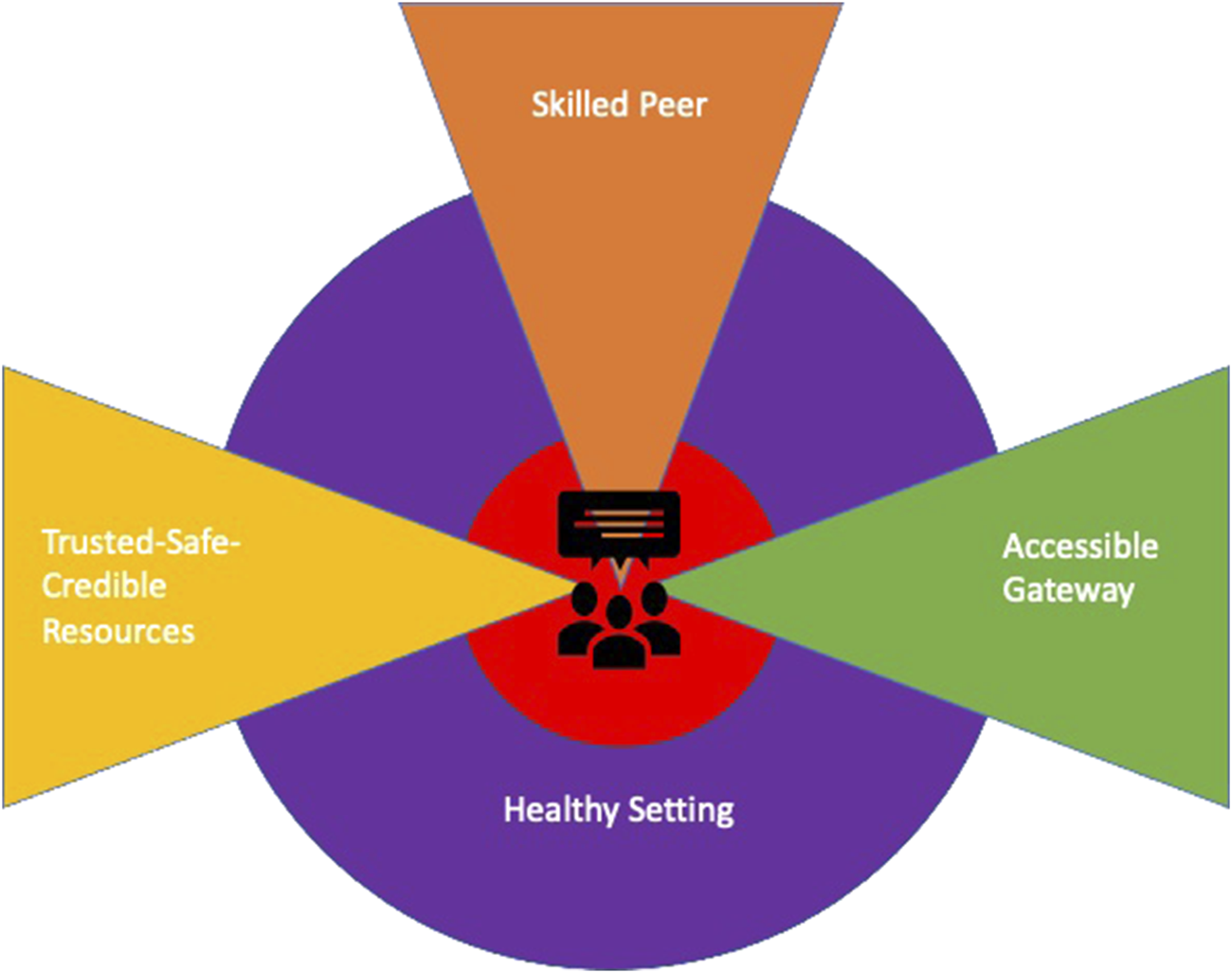

Results: A total of 57 documents were included. The overarching programme theory was developed from the analysis of these documents and comprised of a social prescribing pathway with the following components: (1) An Accessible Gateway, (2) A Skilled Peer, (3) Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources, and (4) A Healthy Setting.

Conclusion: A Realist Programme Theory was developed—this model and associated principles will provide a theoretical basis for the implementation of social prescribing pathways within higher education. Whilst the direct project outputs are of particular significance to the UK HE audience, the underpinning principles can support practice within the global arena.

Introduction

Within the United Kingdom (UK), it is estimated that up to 20% of Primary Care appointments are for social or economic, rather than medical reasons [1–3]. Mental health issues are now more prevalent within the general population, a situation that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 5]. UK policy and legislative documents have called for new and innovative services to address these challenges [6–8], indicating that resources should deliver holistic support for citizens which promote health and wellbeing.

Social prescribing is a globally evolving initiative [9] which has the potential to address these pressures and prevent future ill health. Models of social prescribing are heterogeneous and highly complex [10, 11], varying in structure, intensity of service provision, and complexity [12]. Models typically comprise a link worker, also known as a community connector, navigator, or wellbeing advisor, who works with an individual to identify goals and needs and connect them with non-medical community resources [13, 14]. A range of models have emerged over the past decade, varying in structure, complexity, and intensity of provision [15]. Services include informal signposting to community resources and assets, through to holistic support where link workers work closely and co-productively with the individual over a series of appointments to identify resources to meet their needs [12].

Social prescribing interventions have been targeted at a range of population groups and conditions including people who are socially isolated, older individuals experiencing sensory impairment, and those with long term health issues [14, 16–20], but Higher Education (HE) students and young people remain a demographic where further investigation regarding the implementation of social prescribing is warranted. Student wellbeing levels are considerably lower than the general population [21], and marked increases in student wellbeing issues have been observed in recent years [22]. Factors including change of locality, the pressures of independent living and learning, new personal responsibilities all contribute to reduced wellbeing and challenges of adjustment are particularly amplified for mature students, those with declared disability, and learners from Black and Asian Minority Ethnic groups [21, 23–25].

In addition, the student population continue to be considerably affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, impacting on social isolation, stress, anxiety, loneliness, social interactions, and wellbeing [26–28]. Whilst several strategies have been developed [29], effectively supporting student wellbeing remains difficult. Given the struggles experienced by this specific group and the large and increasing number of individuals attending HE [25], the potential for social prescribing within this environment merits further exploration.

This Rapid Realist Review seeks to evaluate social prescribing in HE—informing the development of a service model which will effectively meet the varying needs of a range of individuals. To achieve this aim, five specific review questions were devised:

1. What forms of social prescribing interventions are specifically targeted at HE students?

2. How do HE students access social prescribing interventions targeting them?

3. When do HE students access social prescribing interventions?

4. For whom do social prescribing interventions work?

5. To what extent does social prescribing work for HE students?

Methods

Conventional approaches to the evaluation of interventions such as the systematic review focus predominantly upon outcome, i.e., what works [30]. In order to understand how a scalable social prescribing pathway may be developed for students in HE, it is imperative to appreciate the impact of context; to understand how, why, for whom, to what extent, and in what context the intervention works [31]. Realist methodology satisfies these demands; it is a theory-driven approach to the synthesis of evidence, the goal of which is to build a programme theory that explicates what the intervention is, and how it can be expected to work. The Realist Review method is grounded within generative causation, meaning that to infer a causal relationship between an intervention (I) and outcome (O), one must understand the underpinning mechanism (M) connecting them, as well as the context (C) in which they occur. Using the Realist approach, we have unpacked the Context-Mechanism-Outcome configurations (CMOCs) underpinning existing pathways, and in doing so, have built a Realist programme theory of social prescribing for students in HE.

Developing the Project Scope

Refining the focus of the review and developing scope took place collaboratively with an Advisory Group [32] comprising key student services personnel, student representatives, content experts, 3rd Sector partners, and members of the research team from across both institutions. A Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO), and search strategy were developed (Table 1), and informal scoping of existing evidence and policy was undertaken to pilot test search terms and build familiarity with existing knowledge relating to social prescribing. Whilst these initial searches indicated that literature focusing specifically upon the use of social prescribing with HE students was limited, examining similar interventions in which social prescribing had been employed, allowed the detection of demi-regularities [33, 34] or causal patterns that formed the basis of CMOCs within this project.

TABLE 1

| PICO framework | |

|---|---|

| Patient/Population Under Study | HE Students |

| Intervention | Social Prescribing |

| Comparison | Students sourcing own wellbeing interventions |

| Outcome | Impact of specified Social Prescribing model upon overall student wellbeing |

| Search Terms | |

| Search Term | Alternate |

| Wellbeing | Wellbeing, Wellbeing, Wellness, |

| Resilience | Resilien*, Hardiness, Reserve, Coping, |

| Isolation | Isolat*, Separat*, Lonel*, Remot*, Living Away, Social Isolation |

| Relationships | Relationship*, Connection*, |

| Local Community | Locality, Neighbourhood, Community Group, |

| Lifestyle | Physical Health, Mental Health, Healthy Living, |

| Social Prescribing | Social Prescr*, Link Worker*, Link Navigator, Link Coordinator, Community Refer*, Community Connect*, Community Coordinator, Community Navigator, Community Champion, First Contact Practitioner, Local Area Coordinator, Social Capital, Community Asset*, |

| Student | Student*, Learner*, Part-time Student*, Rural Student*, Liberation Groups, Mature Student*, Students with Declared Disabil*, |

| Higher Education | HE, FE in HE, University, Tertiary Education |

| Self-Efficacy | Self-Management |

| Literature Sources | |

| Documents | |

| Primary Care Hub (2018) Social Prescribing in Wales: Final Report. Cardiff: Public Health Wales | |

| Social Services and Wellbeing (Wales) Act 2014 | |

| Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act, 2015 | |

| Welsh Government (2018) A Healthier Wales: Our Plan for Health and Social Care. Cardiff: Welsh Government | |

| Databases | |

| ASSIA, British Education Index, CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, ProQuest Psychology Journals, PsychInfo, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Social Care Online, Web of Science | |

| Grey Literature | |

| Local Authority Websites, Third Sector Websites, University Websites, HE Sector Policy Documents, ‘OpenGrey’ | |

| Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria | |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| English language | Students in FE or Continuing Education |

| Published literature | |

| Grey literature | |

| Students in HE | |

| Date Range | |

| All available entries up to April 2020 | |

| Search Strings | |

| Concept 1 Wellbeing | |

| Wellbeing OR “Wellbeing” OR “Wellbeing” OR Wellness | |

| Concept 2 Resilience | |

| Resilien* OR Hardiness OR Reserve OR Coping | |

| Concept 3 Isolation | |

| Isolat* OR Separat* OR Lonel* OR Remot* OR “Living Away” Or “Social Isolation” | |

| Concept 4 Relationships | |

| Relationship* OR Connection* | |

| Concept 5 Local Community | |

| “Local Community” OR Locality OR Neighbourhood OR “Community Group” | |

| Concept 6 Lifestyle | |

| Lifestyle OR “Physical Health” OR “Mental Health” OR “Healthy Living” | |

| Concept 7 Social Prescribing | |

| “Social Prescr*” OR “Link Worker*” OR “Link Navigator” OR “Link Coordinator” OR “Link Co-ordinator” OR “Community Refer*” OR “Community Connect*” OR “Community Coordinator” OR “Community Co-ordinator” OR “Community Navigator” OR “Community Champion*” OR “First Contact Practitioner” OR “Local Area Coordinator” OR “Local Area Co-ordinator” OR “Social Capital” OR “Community Asset*” | |

| Concept 8 Student | |

| Student* OR Learner* OR “Part-Time Student*” OR “part time student*” OR “Rural Student*” Or “Liberation Groups” OR “Mature Student*” OR “Students with Declared Disabil*” | |

| Concept 9 Higher Education | |

| “Higher Education” OR HE OR “FE in HE” OR “Tertiary Education” OR University NOT FE | |

| Concept 10 Self Efficacy | |

| “Self Efficacy” OR “Self-Efficacy” OR “Self Management” OR “Self-Management” | |

| Search Outcomes | |

| Total Hits | 4,338 |

| Duplicates Removed | 2,347 |

| Including Grey Literature from Advisory Group | 2,358 |

| For Abstract Screen | 349 |

PICO & Literature Searches (University of South Wales, United Kingdom. 2022).

Search Strategy

An Initial Programme Theory (IPT) should be the starting point within any Realist Review—encapsulating views of the research team and Advisory Group regarding how and why an intervention should work [35]. Search terms encompassing the IPT were initially drafted in conjunction with the Advisory Group, executed, and refined iteratively as the IPT was developed. Following further consultation with an information specialist, twelve databases were searched (Table 1). Grey literature obtained from Local Authority and 3rd Sector websites from the UK were additionally interrogated, and further documents were provided by the Advisory Group. Citation chaining was also used to identify other relevant documents throughout the review; however given that a Rapid Realist Review was being undertaken [36], there were limited opportunities to add documents to the review in this way. The search results were exported and de-duplicated within EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia PA, USA) before being fully extracted into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA, USA) for the research team to have full access. A PRISMA diagram outlining the search is presented within Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

PRISMA diagram (University of South Wales, United Kingdon. 2021).

Selecting Documents

Documents were selected based on the degree to which they addressed the research questions, and ultimately contributed to the development of a Refined Programme Theory. Inclusion decisions were made by the full review team based upon relevance - how these data might contribute to theory building, and rigour—the degree to which the methods used to generate these data are plausible and trustworthy [34]. Titles retrieved from the searches were initially screened by MD for salience; any deemed irrelevant were excluded at this stage. An abstract screening tool was developed by the project team and utilised to screen the remaining documents and determine if they met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Where it was unclear if the abstracts met the inclusion criteria, the full text document was retained for screening. Abstract screening was undertaken by MD and CW; ME ensured inter-rater reliability by screening 10% of the overall abstracts. Full text screening was completed by MD and CW to establish the final data set for inclusion, and this was transferred to NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for coding. Again, 10% of the documents were screened by ME, and any disagreements were resolved through engagement and discussion with the project Advisory Group.

Existing evidence was interrogated to further confirm, refine or refute the IPT, leading to the development of an abstracted model explaining how and why our programme works, for whom, to what extent, and in what circumstances [34]. Through an iterative process of data collection, analysis and synthesis [32], CMOCs were built that continued to shape the emerging programme theory. Whilst qualitative appraisal frameworks such as the CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [37] may have significant utility within conventional systematic reviews, they must be applied cautiously in a Realist Review in order to avoid excluding documents which could significantly impact upon programme theory development [32] - even documents that lack methodologically robustness may still potentially contain “nuggets” that could advance the theory building process [38]. Discussing the content of any potentially problematic document within the research team and Advisory Group was helpful in this respect, as was following the RAMESES Quality Standards for Realist Synthesis [39] and selecting literature that provided ‘conceptually rich’ accounts of phenomena [40].

Extracting and Organising the Data

Once the data set was finalised (Table 2), full text documents were sourced and located within a shared drive accessible by all team members and transferred to NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for coding. A data extraction tool using Microsoft MS Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA, USA) was also employed to collate information regarding the authors, date, source, nature of intervention, potential CMOCs, overall themes and any reference to substantive theory.

TABLE 2

| Authors | Date | Article title | Country | Study design | Sample/Setting | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas, M. A. Eliyana, P. A. Ekowati, D. D. Saud, M. M. Raza, M. A. Wardani, M. R. | 2020 | Data set on coping strategies in the digital age: The role of psychological wellbeing and social capital among university students in Java Timor, Surabaya, Indonesia | Indonesia | Survey questionnaire | University students | To examine the effects of technology on coping strategies & psychological wellbeing |

| Agadullina, E. R. Lovakov, A. Kiselnikova, N. V. | 2020 | Does quitting social networks change feelings of loneliness among freshmen? An experimental study | Russia | Experimental design | Freshman psychology students | To examine the impact of quitting social networks upon loneliness and isolation |

| Alizadeh, Z. Safaian, A. Mahmoodi, H. Shaghaghi, A. | 2018 | Pathways between authentic happiness and health promoting lifestyle profiles of the university students in Tabriz, Iran | Iran | Cross-sectional study | Iranian university students | To explore the relationship between and other health promoting behaviours |

| Altinyelken, H. K. | 2018 | Promoting the psychosocial wellbeing of international students through mindfulness: A focus on regulating difficult emotions | Netherlands | Qualitative study | International students at a Dutch university | To explore the potential of a mindfulness programme for providing psycho-social support to international students in higher education |

| Anderson, S. Fast, J. Keating, N. Eales, J. Chivers, S. Barnet, D. | 2017 | Translating knowledge: Promoting health through intergenerational community arts programming | Canada | Community participatory research project | Older adults and university students | To explore the health and wellbeing benefits of participation in an intergenerational community arts programme |

| Ashbaugh, K. Koegel, R. Koegel, L. | 2017 | Increasing social integration for college students with autism spectrum disorder | United States | Experimental design | University students with a confirmed diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder | To assess whether a structured social planning intervention would increase social integration for college students with Autistic Spectrum Disorder |

| Bailey, K. M. Frost, K. M. Casagrande, K. Ingersoll, B. | 2020 | The relationship between social experience and subjective wellbeing in autistic college students: A mixed methods study | United States | Mixed methods study | University students who had identified themselves to the college’s disability resource centre | To explore the relationship between the college social experience and subjective wellbeing in autistic student in the Midwestern United States |

| Barsell, D. J. Everhart, R. S. Miadich, S. A. Trujilo, M. A. | 2018 | Examining health behaviours, health literacy, and self-efficacy in college students with chronic conditions | United States | Survey questionnaire | Undergraduate students from a Mid Atlantic US university with a self-identified chronic health conditions lasting >3 months | To examine associations between health literacy, self-efficacy, and health behaviours in a sample of college students with chronic conditions |

| Bertotti, M.Frostick, C. Hutt, P. Sohanpal, R. Carnes, D. | 2018 | A Realist Evaluation of social prescribing: an exploration into the context and mechanisms underpinning a pathway linking primary care with the voluntary sector | United Kingdom | Realist Evaluation | Users of social prescribing services | To use a Realist approach in order to evaluate a social prescribing pilot in the areas of Hackney and City in London. |

| Bird, A. Pincavage, A. | 2016 | A curriculum to foster resident resilience | United States | Case study | Medical students | To evaluate the impact of a ‘resilience curriculum’ upon resilience and wellness |

| Boda, Z. Elmer, T. Voros, A. Stadtfeld, C. | 2020 | Short-term and long-term effects of a social network intervention on friendships among university students | Switzerland | Field experiment & observational study | Undergraduate university students | To investigate the short-term and long-term effects of randomized first contact opportunities on friendship networks in an emerging community of first-year undergraduate students |

| Bouteyre, E. Maurel, M. Bernaud, J. | 2006 | Daily hassles and depressive symptoms among first year psychology students in France: The role of coping and social support | France | Survey questionnaire | First year undergraduate university students | To explore the impact of coping strategies upon daily hassles and depressive symptoms |

| Brunsting, N. C. Zachry, C. Liu, J. Bryant, R. Fang, X. Wu, S. Luo, Z. | 2019 | Sources of perceived social support, social-emotional experiences, and psychological wellbeing of international students | United States | Structural equation modelling | Graduate and undergraduate students | To test whether specific social influences could enhance international students’ belonging and wellbeing and attenuate loneliness |

| Budzynski-Seymour, E. Conway, R. Wade, M. Lucas, A. Jones, M. Mann, S. Steele, J. | 2020 | Physical activity, mental and personal wellbeing, social isolation, and perceptions of academic attainment and employability in university students: The Scottish and British active students’ surveys | United Kingdom | Cross sectional surveys | University and college students in Scotland and the United Kingdom | To explore the relationships between physical activity and personal wellbeing within UK university students |

| Byrom, N. | 2018 | An evaluation of a peer support intervention for student mental health | United Kingdom | Cohort study | Students within 8 UK universities | To identify students likely to attend peer support and evaluate the acceptability and impact of the intervention |

| Chandler, G. E. Kalmakis, K. A. Chiodo, L. Helling, J. | 2020 | The efficacy of a resilience intervention among diverse, at-risk, college athletes: a mixed-methods study | United States | Mixed methods study | US college athletes | To assess the efficacy of a strengths-based resilience intervention upon perceptions of stress, resilience, emotional awareness, and belonging among student-athletes. |

| Chow, K. M. Tang, W. K. Chan, W. H. Sit, W. H. Choi, K. C. Chan, S. | 2018 | Resilience and wellbeing of university nursing students in Hong Kong: A cross sectional study | China | Cross sectional descriptive correlation design | Chinese undergraduate nursing students | To explore resilience levels in nursing students and its relationship with wellbeing |

| Karishma, C. Armstrong, S. Bean, S. | 2018 | Supporting students facing mental health challenges | United States | Survey questionnaire | Graduate and undergraduate students | To assess anxiety levels in university students and consider potential support strategies |

| Daddow, A. Cronshaw, D. Daddow, N. Sandy, R. | 2019 | Hopeful cross-cultural encounters to support student wellbeing and graduate attributes in Higher Education | Australia | Qualitative programme evaluation | University students | To evaluate an extracurricular programme that enabled interfaith and cross-cultural dialogue |

| Denovan, A. Macaskill, A. | 2017 | Stress, resilience and leisure coping among university students: Applying the broaden-and-build theory | United Kingdom | Structural equation modelling | University students | To investigate whether resilience predicts leisure coping and positive affect and whether this relationship is predictive of higher levels of wellbeing |

| Donoghue, J. O’Rourke, M. Hammond, S. Stoyanov, S. O’Tuathaigh, C. | 2020 | Strategies for enhancing resilience in medical students: a Group Concept Mapping analysis | Ireland | Group Concept Mapping analysis | Undergraduate medical students | To use GCM software to explore and categorise resilience strategies employed by third year undergraduate medical students |

| Dunn, L. B. Moutier, C. | 2008 | A conceptual model of medical student wellbeing: Promoting resilience and preventing burnout | International | Literature Review | Undergraduate medical students | To review the literature on medical student stress, coping, and wellbeing in order to develop a model of medical student coping termed the “coping reservoir.” |

| Enrique, A. Mooney, O. Salamanca-Sanabria, A. Lee, C. T. Farrell, S. Richards, D. | 2019 | Assessing the efficacy and acceptability of an internet-delivered intervention for resilience among college students: A pilot randomised control trial protocol | Ireland | Randomised control trial (protocol) | University students | To evaluate a newly developed internet-delivered intervention for resilience provided with human or automated support |

| Galante, J. Dufour, G. Vainre, M. Wagner, A. P. Stochl, J. Croudace, T. J. Benton, A. Howarth, E. Jones, P. B. | 2016 | Provision of a mindfulness intervention to support university students’ wellbeing and resilience to stress: preliminary results of a randomised controlled trial | United Kingdom | Randomised control trial | University students | To assess the efficacy of an 8 week mindfulness course versus usual mental health provision |

| Gee, K. A. Hawes, V. Cox, N. A. | 2019 | Blue Notes: Using songwriting to improve student mental health and wellbeing. A pilot randomised controlled trial | United Kingdom | Wait-list randomised control trial | University students with self-identified anxiety | To assess the efficacy of a weekly songwriting programme versus no intervention |

| Gieck, D. J. Olsen, S. | 2007 | Holistic wellness as means to developing a lifestyle approach to health behaviour among college students | United States | Cohort study | University students | To examine the influence of a holistic model of wellness on activity level among obese and sedentary college students |

| Haas, J. Pamulapati, L. G. Koenig, R. A. Keel, V. Ogbonna, K. C. Caldas, L. M, | 2020 | A call to action: Pharmacy students as leaders in encouraging physical activity as a coping strategy to combat student stress | United States | Commentary paper | Undergraduate pharmacy students | This commentary is a call to action for student pharmacists to take shared ownership over improving the current crisis of student wellbeing - empower their students to guide the improvement of wellness. |

| Rand Health | 2016 | Campus Climate Matters: Changing the Mental Health Climate on College Campuses Improves Student Outcomes and Benefits Society. | United States | Research brief | University students | To discuss a CalMHSA prevention & early intervention programme targeting health and wellbeing |

| HEFCW | 2019 | HE for a Healthy Nation: Student Wellbeing and Health | United Kingdom (Wales) | Report | University students | Report examining a range of student wellbeing strategies. |

| Harrer, M. Adam, S. H. Baumeister, H. Cuijpers, P. Karyotaki, E. Auerbech, R. P. Kessler, R. C. Bruffaerts, R. Berking, M. Ebert, D. D. | 2019 | Internet interventions for mental health in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis | International | Systematic review and meta-analysis | University students | To search for randomized trials examining psychological interventions for the mental health, well‐being, and functioning of university students |

| Herrero, R. Adriana, M. Giulia, C. Etchemendy, E. Banos, R. Garcia-Palacios, A. Ebert, D. D. Franke, M. Berger, T. Schaub, M. P. Goerlich, D. Jacobi, C. Botella, C. | 2019 | An Internet based intervention for improving resilience and coping strategies in university students: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial | International | Randomised control trial (protocol) | University students | To evaluate the efficacy of an unguided internet-based intervention to enhance resilience in university students |

| Holt, M. Powell, S. | 2017 | Healthy Universities: a guiding framework for universities to examine the distinctive health needs of its own student population | United Kingdom | Survey questionnaire | University students | To examine the student health behaviours of one university so that future initiatives can be tailored to its own student population |

| Husk, K. Blockley, K. Lovell, R. Bethel, A. Lang, I. Byng, R. Garside R. | 2019 | What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A Realist Review | United Kingdom | Realist Review | Users of social prescribing services | To develop a programme theory articulating the ways in which social prescribing works, for whom, and in what circumstances |

| Hussain, R. Guppy, M. Robertson, S. Temple, E. | 2013 | Physical and mental health perspectives of first year undergraduate rural university students | Australia | Survey questionnaire | Rural university students | To examine the physical and mental health issues for first year Australian rural university students and their perception of access to available health and support services |

| Kampel, L. Orman, J. O’Dea, B. | 2017 | E-mental health for psychological distress in university students: A narrative synthesis on current evidence and practice | Australia | Narrative synthesis | University students | To outline the current knowledge and application of e-mental health programs, and to discuss ways that prevention and intervention programs delivered via the Internet and smartphones can be taken to scale to reach a larger number of students to improve their mental health |

| Knight, A. LaPlaca, V. | 2013 | Healthy Universities: taking the University of Greenwich Healthy Universities Initiative forward | United Kingdom | Commentary paper | University students | The paper sets out the background to the national Healthy Universities initiative, briefly outlines a pilot initiative; and ends by considering the broader developments in policy and practice |

| Lattie, E. G. Adkins, E. C. Winquist, N. Stiles-Shields, C. Wafford, E. Graham, A. K. | 2019 | Digital mental health interventions for depression, anxiety, and enhancement of psychological wellbeing among college students: systematic review | International | Systematic review | University students | To review the literature on digital mental health interventions focused on depression, anxiety, and enhancement of psychological wellbeing among samples of college students to identify the effectiveness, usability, acceptability, uptake, and adoption of such programs |

| Montagni, I. Cosin, T. Sagara, J. A. Bada-Alonzi, J. Horgan, A. | 2020 | Mental health-related digital use by university students: a systematic review | International | Systematic review | University students | To summarize and critique studies of mental health-related digital use by students worldwide, to support the implementation of future digital mental health interventions targeting university students. |

| Murr, A. H. Miller, C. Papadakis, M. | 2002 | Mentorship through advisory colleges | United States | Case study | Medical students | To outline the development and implementation of an advisory college system that supports medical student wellbeing |

| Oades, L. G. Robinson, P. Green, S. Spence, G. B. | 2011 | Towards a positive university | Australia | Commentary paper | University students | The paper explores the concept of the “Positive University.” |

| Owens, A. R. Loomes, S. L. | 2010 | Managing and resourcing a program of social integration initiatives for international university students: what are the benefits? | Australia | Mixed methods | International students studying at Australian universities | To report the results of a survey of 446 CQUniversity international students who have had access to enhanced social integration opportunities for integration as well as a focus-group discussion with staff and students |

| Palma-Gomez, A. Herrero, R. Banos, R. Garcia-Palacios, A. Castaneiras, C. Fernandez, G. L. Llull, D. M. Torres, L. C. Barranco, L. A. Cardenas-Gomez, L. Botella, C. | 2020 | Efficacy of a self-applied online program to promote resilience and coping skills in university students in four Spanish-speaking countries: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial | International | Randomised control trial (protocol) | University students | To evaluate the efficacy of an unguided internet-based intervention to enhance resilience in university students |

| Papadatou-Pastou, M. Campbelll-Thomas, L. Barley, E. Haddad, M. LaFarge, C. McKeown, E. Simeonov, L. Tzotzoli, P. | 2019 | Exploring the feasibility and acceptability of the contents, design, and functionalities of an online intervention promoting mental health, wellbeing, and study skills in Higher Education students | United Kingdom | Cohort study | Graduate and undergraduate students | To evaluate the effectiveness of this intervention protocol in comparison with an active control condition targeting healthy lifestyle, and a waiting list control condition |

| Primary Care Hub | 2018 | Social Prescribing in Wales: Final Report | United Kingdom (Wales) | Report | Users of social prescribing services | A report providing an overview of the evolution, efficacy, and implementation challenges of social prescribing in Wales |

| Randstad | 2020 | A Degree of Uncertainty: Student Wellbeing in Higher Education | United Kingdom | Survey | University students | To explore the perceptions of students regarding their perceived levels of support whilst studying in UK universities |

| Ray, E. C. Arpan, L. Oehme, K. Perko, A. Clark, J. | 2019 | Helping students cope with adversity: a test of the influence of a web-based intervention on students’ self-efficacy and intentions to use wellness-related resources | United States | Randomised control trial | Undergraduate university students | To assess the efficacy of an online student wellness intervention versus usual provision |

| Short, B. Lambeth, L. David, M. Ryall, M. A. Hood, C. Pahalawatta, U. Dawson, A. | 2019 | An immersive orientation programme to improve medical student integration and wellbeing | United States | Mixed methods | Medical students | To evaluate an immersive orientation programme aimed at promoting student wellbeing through social connectedness |

| Sibley, S. Sauers, L. Daltrey, R. | 2019 | Humanity and Resilience Project: The development of a new outreach program for counselling centres at colleges and universities | United States | Case study | University students | To present an overview of a programme developed to increase resilience by encouraging social connection within students at a US university |

| Stalman, H. M. | 2019 | Efficacy of the My Coping Plan mobile application in reducing distress: A randomised controlled trial | Australia | Randomised control trial | University students with self-reported elevated levels of distress | To assess the efficacy of an online strengths-focused coping plan app versus usual provision |

| Thomas, K. Bendsten, M. | 2019 | Mental Health Promotion Among University Students Using Text Messaging: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Mobile Phone-Based Intervention | Sweden | Randomised control trial (protocol) | University students | To test the efficacy of a mobile phone–based intervention on positive mental health |

| Thomas, S. S. | 2009 | Top 10 Strategies for Bolstering Students’ Mental Resilience | United States | Commentary paper | University students | Commentary paper outlining a series of strategies that may be effective in increasing student resilience levels |

| Thorley, C. | 2017 | Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities | United Kingdom | Report | University students | A report outlining setting forth the challenges surrounding student mental health and wellbeing, and outlining a series of interventions that may be helpful in addressing these |

| Tierney, S. Wong, G. Roberts, N. Boylan, A. Park, S. Abrams, R. Reeve, J. Williams, V. Mahtani, K. R. | 2020 | Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a Realist Review | United Kingdom | Realist Review | Users of social prescribing services | To understand how such social prescribing connector schemes work, for whom, why and in what circumstances |

| Wawera, A. S. McCamley, A. | 2019 | Loneliness among international students in the UK | United Kingdom | Mixed methods | International students at UK universities | To explore loneliness in an international student population in a single university |

| Webster, N. L. Oyebode, J. R. Jenkins, C. Bicknell, S. Smythe, A. | 2020 | Using technology to support the emotional and social wellbeing of nurses: A scoping review | United Kingdom | Scoping review | Undergraduate nursing students | To review the literature on the use of technology to offer emotional and social support to nurses |

| Welsh Government | 2018 | A Healthier Wales: Our Plan for Health and Social Care | United Kingdom (Wales) | Strategy Document | Population of Wales | The document sets out a long term future vision of a whole system approach to health and social are which is focussed upon health and wellbeing, and on preventing illness |

| Wiljer, D. Johnson, A. McDiarmid, E. Abi-Jaoude, A. Ferguson, G. Hollenberg, E. Van Heerwaarden, N. Tripp, T. Law, M. | 2017 | Thought Spot: Co-Creating Mental Health Solutions with Post-Secondary Students | Canada | Case study | University students | To explore the development, utilisation, and impact of a web-based platform that supports students in seeking mental health and wellbeing support |

Final Data Set (University of South Wales, United Kingdom. 2022).

Synthesizing the Evidence and Building the Programme Theory

Full text was first examined by MD who identified initial themes or tentative ‘bucket codes’ that may reflect a Context, Mechanism, Outcome, or any combination of these. This process continued iteratively as CMOCs were developed, allowing the emerging Programme Theory to be supported, refined, or refuted. CW simultaneously double coded 20% of the data set and both reviewers discussed and agreed the emerging CMOCs. The process was further supported by ME, who was involved in all discussions regarding coding, the development of CMOCs, and the Refined Programme Theory.

The initial bucket codes remained very broad but proved to be a useful stepping-stone as we transitioned from analysis to synthesis. Three key reasoning strategies were employed synergistically to facilitate data analysis, synthesis, and theory building. Careful “observation” of the data resulted in the inductive generation of codes, whilst themes or propositions from the initial programme theory/substantive theory were tested against the data in a deductive manner to build CMOCs. Finally, retroductive reasoning involved using both induction and deduction as well as drawing on one’s owns insights in a manner consonant with the abductive reasoning of Peirce [41] in order to elucidate causal mechanisms [42]. A full list of CMOCs can be found within Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Theme | CMOC No (Paper): | CMOC |

|---|---|---|

| Accessible Gateway | 23 | When interventions and/or services are perpetually available online (C), Students feel that there is always support (M), and this increases their sense of safety and overall wellbeing (O) |

| 49 | When students have access to an app that enables them to view a range of alternative wellbeing provision (C), They will engage with healthy coping resources (M) and develop an individual coping plan (O) | |

| 57 | When a Social Prescribing pathway is linked to existing IT platforms (C), stakeholders will perceive it as easy to use (M) and engage more readily (O) | |

| 38 | When services provide HE students who are vulnerable with useful digital resources (C) they are more likely to engagement with these (O), because they do not feel judged or stigmatised by anyone (M) | |

| 46 | When web-based interventions link students into campus resources (C), the students feel less stigmatized (M), and there is greater uptake of Mental Health and Wellbeing services | |

| 29 | When resources are made available on-site simultaneously from the university and other partners (C), students feel a greater sense of agency (M) becoming aware of the support available (O) | |

| 29 | When student wellbeing champions are present at high traffic student ‘hotspots’ (C), there is a sharing of resources (M), an increased awareness of the help that is available (O) | |

| Skilled Peer | 51 | When the student is confident that their needs will be met (M) by a Gatekeeper’s knowledge of early interventions (C), they will engage with the service (O) |

| 57 | When navigators demonstrate a genuine desire to help by offering personalised support (C), users will believe that they can benefit from the interaction (M) and engage with the service and subsequent Social Prescription (O) | |

| 52 | When trusted friends, tutors and parents are involved when students are struggling with wellbeing (C), there is a normalising of stressful experiences (M) and a subsequent building of resilience and improved wellbeing (O) | |

| 57 | When establishing the Social Prescribing pathway (C), third sector and community services will buy into the navigator role (O), if they believe that the referrals received are appropriate (M) | |

| 57 | When a user perceives the navigator to be part of a formal mental health or social services structures (C), a fear of stigmatising (M) may prevent them engaging with the services (O) | |

| 52 | When peer support is provided by student volunteers (C), there is an externalising of MH and wellbeing issues (M), and students deal more effectively with mental health & wellbeing challenges (O) | |

| 16 | When student volunteers provide wellbeing peer support (C), they share coping strategies (M), building and maintains positive mood (O) | |

| 27 | When students engage in peer-led wellness activities (C), they feel a shared connection and view the activities to be authentic and trustworthy (M), and this increases engagement (O) | |

| 57 | Developing systems providing supervision or peer support (C), enables anxieties regarding the role to be shared and explored (M), buffering the psychological pressure the navigator may experience (O) | |

| Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources | 38 | When credible digital resources are provided (C) students will have confidence and trust in them (M) with consequent high levels of uptake and sustained engagement (O) |

| 34 | When a library of online self-help resources is provided (C), students will believe that self-improvement is possible (M), and their agency and self-efficacy will increase (O) | |

| 56 | When students digitally curate community-based wellbeing resources (C), they share their knowledge with peers (M), building support networks and increasing social capital | |

| 07 | When students and older community members come together and collaborate on a shared activity (C), social connections are built between the university and wider community (M), and there is increased social capital and associated wellbeing for all parties (O) | |

| 58 | When a referral is made to a community asset (C), the service user has opportunities to meet and share experience with those within and beyond the university (M), building their social capital | |

| 57 | When developing a Social Prescribing pathway (C), third sector and community services should be active co-producers of the scheme (M), as this enables them to feel like valued partners (O) | |

| A Healthy Setting | 36 | When organisations adopt a settings-based approach in which university structures, policies, and processed are integrated with wider community health promotion (C), members will feel empowered to make healthy choices within a supportive environment (M), resulting in increased satisfaction & productivity for the whole university community (O) |

| 28 | When organisations create a positive and enabling campus environment where mental health and wellbeing are supported (C), Students feel confident that they will not be stigmatized for accessing support (M) and engage readily with campus services (O) | |

| 32 | When organisations using a Healthy University approach (C), identifying the needs of their specific student populations (M), relevant programmes and interventions are developed (O) |

CMOC List (University of South Wales, United Kingdom. 2022).

Results

Document Characteristics

Overall, 57 documents were included in this Realist Review; none made explicit reference to social prescribing pathways operating within higher education. A range of mental health and wellbeing interventions were however identified; some of these functioned in isolation, whilst others were part of a broader initiative. Documents were from the United Kingdom (n = 18), United States (n = 17), Europe (n = 10), Australia (n = 6), Canada (n = 2), Asia (n = 2), Russia (n = 1) and Iran (n = 1).

Main Findings

The focus of this review was to develop a programme theory explicating how social prescribing might be most optimally introduced to maximise benefit for both those using the services, and the organisations within which the pathways are hosted. Whilst literature relating directly to the use of social prescribing for HE students was limited, several studies articulated processes or pathways that were analogous to elements of the social prescribing process. Examples included using digital systems that linked those with wellbeing or mental health issues with services, mapping assets or resources within the university or wider community, and providing those undertaking a link worker role with effective training and support. Developing CMOCs from the literature also provided opportunities to examine social prescribing pathways created for other groups, e.g., older people living with chronic conditions, identifying demi-regularities [33, 34] that informed the programme theory developed within this project. Analysis of the data surfaced a programme theory in which four specific themes were supported by CMOCs, i.e., An Accessible Gateway, A Skilled Peer, Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources, and a Healthy Setting.

An Accessible Gateway

When examining the literature surrounding systems or pathways for those experiencing mental health or wellbeing issues, the issue of routes into support begin to clearly surface as both an issue, and an area for careful consideration. The need for an accessible provision delivered both physically and virtually emerge as a means of reducing stigma associated with services, sharing resources, and (through a process of sharing experiences) developing positive coping strategies [11]. When services are delivered conventionally, students may find accessing these more difficult, particularly if they are not living on campus and only physically attend for limited periods during a week—issues that are further amplified in the current COVID-19 pandemic period. Web-based provision that includes an automated component may be useful in providing support for these groups [43, 44]. The range of provision is not always readily discernible when users are initially attempting to access the pathway, and this can be particularly problematic if services are offered by a range of departments within the university and beyond.

This issue was highlighted in a study examining the inception of social prescribing pathways within Primary Care, indicating that in order to increase engagement for all stakeholders, pathways should be integrated with existing systems as far as is reasonably practicable [11].

The range of mental health and wellbeing resources continues to increase [45], but those wishing to use the services may not be aware of the scope of provision, or appropriateness of pathways; a single platform in which these are located may be particularly useful in this respect [44, 46].

A number of documents in the review highlight the stigma associated with formally seeking support [24, 47–51], and this is increased for international students, or those from deprived socio-economic backgrounds [52]. These CMOCs indicate that digital or web-based resources may be particularly useful in ameliorating this issue, empowering students to access support without fear of negative perceptions or judgements.

Discussions around accessibility within the literature focus predominantly upon digital or web-based resources, but CMOCs within this theme also relate to the physical location, highlighting a number of considerations for any physical hubs [49]. Whilst there is a need to mirror digital provision in terms of centralising information regarding resources, the data also highlight the role that fellow students can play in raising awareness of wellbeing resources. Although physically locating student wellbeing services in one physical space may be convenient, the literature suggests that locating peers with knowledge of wellbeing resources within student-centric spaces such as cafés, libraries, or social learning spaces may increase fluency with the services that are available within and potentially beyond the institution [49].

A Skilled Peer

The second theme emerging from this review focuses upon those facilitating the social prescription. The link worker or navigator role is complex, multifaceted, and continually evolving [15, 53], requiring a wide range of attributes including mental health first aid, safeguarding, advanced interpersonal skills and motivational interviewing, in addition to a comprehensive knowledge of the resources available locally [10, 54]. There is also significant variation in scope, ranging from the “signposting” of services through to a “holistic” model involving significant engagement with clients and intense support throughout the pathway [12]. The CMOCs developed within this theme reflect these challenges—highlighting the knowledge of the navigator, and the importance of trust and confidence in building a supportive relationship between user and link worker [11, 55]. Such attributes are not only integral in building relationships with users of the social prescribing pathway. In order to achieve “Buy In” from those who receive the referral, the navigator must also be viewed as skilled, competent, and capable of generating appropriate referrals to services [11].

When developing a social prescribing pathway within this setting, the value of peer involvement also emerges strongly; the sense of connection and sharing of a common experience translating into the normalising of mental health and wellbeing issues, and development of resilience [52]. The literature also surfaces the potentially stigmatising effect of engagement with conventional mental health services, indicating that a less ‘formal’ pathway with peer involvement may ameliorate this issue.

Peer input into a social prescribing pathway is viewed as accessible & authentic, facilitating the externalisation of wellbeing issues, and affording a sharing of coping strategies with the pathway user [56, 57].

Whilst the potential efficacy of a peer-led service is supported by the data, the literature also recognises not only the need for effective training, but the potential psychological pressure associated with the navigator role—with processes such as clinical supervision highlighted as important in buffering against these [11]. The review indicates that those undertaking the navigator role must be able to facilitate trusting relationships with those using the services and possess a knowledge of the available interventions. They must also have the ability to select interventions that are appropriate for each user of the pathway; failing to do this effectively will result in a loss of “buy in” and reduced engagement not only from users of the service, but also those providing social prescribing assets within the wider community. The potential psychological burden for those undertaking the navigator role is acknowledged, and buffering systems must be in place. The review data advocates peer involvement within a pathway, but how this may be operationalised is less clear given the issues around training and support.

Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources

The literature and associated CMOCs here illustrate not only the importance of developing a pathway that is accessible and facilitated by an individual with a specific set of attributes, but also the quality of resources and assets that a user may be linked with. A basic web search for wellbeing or mental health resources will generate a significant number of hits, and the nature, scope, and quality of these is particularly challenging for those seeking support [50, 58]. Therefore, a need for resources that have been in some way curated and legitimised emerges from the review. Having access to resources that are perceived as being trustworthy not only increases engagement with services, but also contributes to an individual’s sense of agency and self-efficacy [59]. Consonant with findings in earlier themes, peer involvement within this curation process also emerges as being important for both resource sharing and network building—which then contributes to an increase in the social capital of individuals [46]. Other CMOCs supporting this theme relate to co-productive activity involving both users of the service and those providing assets and resources beyond the university. Cultivating these wider support networks increases the social capital of pathway users, embeds the university within the broader community, and acknowledges and values the contributions of partners [11, 60, 61].

This broader relationship between CMOCs may be perceived within this theme. Co-productive working between the university and wider asset/resource providers not only brings those using services together, but also fosters closely working relationships between those delivering them—developing networks, building social capital, and fostering a common sense of value and ambition. Providing credible resources that are peer-collated and shared, further contributes to this network building whilst increasing agency and overall self-efficacy for those using the pathway.

A Healthy Setting

The final theme emerging from the review focuses upon the macro level institutional climate, articulating how this may impact upon the implementation and ongoing operation of a social prescribing pathway. A number of CMOCs developed echo the “Settings-based Approach” to health promotion outlined within the Ottawa Charter [62], and the “Healthy University” movement that emerged from this [63, 64]. The literature recognises that universities are environments in which a wide range of health and wellbeing initiatives are delivered; the “Healthy University” movement recognises this and focuses upon connecting potentially disparate strategies and mapping and connecting a diverse range of stakeholders within and beyond an organisation to address health and wellbeing. It is also worthy of note that the “Healthy University” movement, and the “Whole University Approach” [65, 66] associated with them not only highlight the importance of connected services within the organisation, but also across the wider community in which the university is situated—a finding that is highly congruent with the fundamental ethos of social prescribing [67].

The challenges faced by universities in terms of engaging students with services has emerged repeatedly within this review, particularly the sense of stigma experienced by those who may be accessing services, and the data highlights the enabling impact of a Healthy Setting upon this [68]. One must of course recognise that although key universal principles may be inducted from the literature, the profile of the organisation and its constituent community must also be carefully considered [63]. Thus, this final theme indicates that a social prescribing pathway will function most effectively when situated within a wider organisational culture that is settings-based and actively champions mental health and wellbeing. Services must be co-ordinated (both within the organisation and across the wider community in which the university is situated), and interventions and approaches must be responsive to the needs of the specific student population.

The Refined Programme Theory

The diagram presented within Figure 2 brings the themes discussed together into a Realist Programme Theory of social prescribing in HE. The student enters the system through an Accessible Gateway that may be physical or digital, and it is here that the individual providing the social prescription is initially encountered. The literature is replete with terms to classify both the scope and nature of this complex and multifaceted function [11, 54], but within this review the term “Navigator” is used. This Skilled Peer facilitates the social prescription through the “What Matters” conversation and/or signposts the student to a repository of Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources. These may include university services, curated information, assets located within the wider community, or a combination of these. Finally, the theory indicates that the social prescribing pathway sits within a wider Healthy Setting context that embodies a core ethos of accessibility, inclusivity, support, and empowerment for all members of the university community.

FIGURE 2

The refined programme theory (University of South Wales, United Kingdom. 2022).

Discussion

We sought to develop a Realist Programme Theory articulating the implementation of a social prescribing pathway within a HE environment. Whilst a range of isolated interventions that may be broadly captured as containing elements of a social prescription surfaced within the literature examined, e.g., an intergenerational arts project involving students and older adults from a local community [60], an online platform that allowed students to crowdsource wellbeing advice [46], we were unable to identify any bespoke pathways for university students. The review therefore represents a novel synthesis and application of the approach. Returning to the Refined Programme Theory (Figure 2), key findings may be drawn from the four themes within the review—relating to the pathway entry point, qualities of the social prescription “provider,” nature and scope of the resources that are available, and broader institutional context within which the pathway is situated. The key findings may be summarised.

The Gateway

This is the first point of contact with the social prescribing pathway, and accessibility was a fundamental consideration. The review data indicate that there is a very strong preference for online access to wellbeing support which should be available at any time and from any location. As large and complex organisations, universities are comprised of many departments offering a range of services; the review acknowledges this, recommending that the social prescribing gateway be linked as seamlessly as possible with existing services—if a bespoke social prescribing IT solution is employed, this should be able to interface with existing systems. For the corresponding physical gateway, attention should be paid to the location. The literature highlights the stigma associated with accessing support for mental health and wellbeing [47, 49–51], and locating a physical hub within a “student owned” space such as a library or café will significantly ameliorate this issue.

The Social Prescriber

The individual instigating a “What Matters” conversation and facilitating the subsequent social prescription is a pivotal component of the pathway. Several of the projects interrogated within the review involved mental health and wellbeing support provided by other students. However, the literature also recognises both the overall complexity and psychological challenges associated with the social prescriber role, and using volunteers in this way would be neither efficacious for the student or nascent social prescriber. Other ways in which peer support can be leveraged may therefore need to be considered when implementing social prescribing pathways, e.g., through peer-led wellness activities [57], or in some form of signposting or advisory capacity [12]. In considering the skills set of the social prescriber, the importance of a knowledgeable individual and well-developed interpersonal skills was evident [61]. However, one must also be cognisant that a social prescribing service requires the nurturing of community assets that exist beyond the university, and if “buy in” is to be achieved from these assets, then the prescriber will also need to cultivate significant Relational Social Capital [69–71], lest the pathway be no more than a signposting system [12] to services within the institution.

The Resources

The third component of the model relates to the trusted and credible resources to which a user of the pathway is referred. The resources made available to the student may consist of services within the university (e.g., finance, counselling, student-run groups), local community assets (e.g., theatre groups, craft groups), digital resources (e.g., apps, online wellness platforms), or any combination of these. Asset mapping is a key process here; the social prescriber identifies potential support systems from within or beyond the university. The online space is also replete with support systems of variable quality, and the review indicates that attempting to discern what may be of genuine value can also be problematic when one is seeking support. For this reason, the review indicates curation of online resources to which those with lower levels of need may be signposted. Providing students with an opportunity to source, curate, and rate both physical and online assets can increase the sense of trust and authenticity for those using the services [46].

The Wider Institutional Setting

The social prescribing pathway here sits within a wider institutional setting. The review data indicates that for a pathway to become more than a “pet” project or series of disparate interventions, the overarching institution must embody a clear commitment to physical and psychological wellbeing, as well as recognising its position as part of the wider community. Adopting such an approach may be challenging for some HEIs, but there is now a ground shift where the importance of a settings-based approach to physical and psychological wellbeing is recognised [63, 67,68].

Revisiting the Review Questions

What Forms of Social Prescribing Interventions are Specifically Targeted at HE Students?

No specific social prescribing pathways directly targeting HE students were surfaced within this Realist Review. Several isolated interventions that contained elements of a social prescription were however identified, and these were drawn upon in terms of developing CMO configurations. The quality of any resources made available to students through social prescribing (Trusted-Safe-Credible Resources) features strongly within the review and has become an integral component of the Programme Theory.

How do HE Students Access Social Prescribing Interventions Targeting Them?

The need for an Accessible Gateway that spans the physical and virtual environments is pivotal here. Likewise, if one is to effectively gain access to social prescribing and its associated assets, the individual functioning in a social prescriber capacity must be a Skilled Facilitator who adopts a holistic approach; cultivating a meaningful relationship through a “what matters” conversation to co-produce a student-centred solution.

When do HE Students Access Social Prescribing Interventions?

The review data indicated that flexibility is paramount; this being particularly well served by the provision of both physical and virtual gateways.

For whom do Social Prescribing Interventions Work?

The interventions that were drawn upon to build the CMOCs and associated Programme Theory spanned a broad range of groups. It is therefore not possible at this stage to discern with any confidence for whom social prescribing interventions work.

To what Extent Does Social Prescribing Work for HE Students?

The extent to which social prescribing works for UK HE students was not discernible from the review data. The Realist Programme Theory here was subsequently tested with participants, and the findings will be reported within a future publication.

Strengths and Limitations

This Rapid Realist Review explores the application of social prescribing within HE. This is a nascent area, and the data indicate the principles of social prescribing may impact positively upon student wellbeing, whilst also facilitating closer working relationships between universities and the wider communities within which they are situated. However, given the limited use of social prescribing approaches within HE, the range of literature and associated CMOCs was sparse, and there was a requirement to draw significant upon demi-regularities [33, 34] i.e., analogous processes functioning within other student wellbeing interventions. Whilst the direct generalisability of findings is confined to the UK Higher Education environment, it is anticipated that the underpinning principles can support the development of practice within the global arena.

Conclusion

Contemporary literature suggests that supporting student with psychological wellbeing is an ongoing challenge; the review undertaken here indicates that leveraging the principles of social prescribing may be one strategy that could be used to ameliorate this. The review has resulted in the induction of a Realist Programme Theory of causation and implementation; articulating a pathway that functions specifically within the UK HE content. The underpinning principles may however be useful in the development of cognate approaches at a global scale.

Statements

Author contributions

MD prepared the initial protocol, developed the search strategy, facilitated the advisory group, undertook the main searches and document screening at title, abstract and full-text level, carried out the coding and development of CMOCs and refined programme theory and prepared the final manuscript. ME supported development of CMOCs and the refined programme theory, contributed to the interpretation of findings and revised the final report. ME reviewed and commented on the manuscript. SW contributed to the formal search strategies, carried out consistency checks on documents in screening and provided practice expertise and perspective. SW reviewed and commented on the manuscript. CW contributed to the development of the protocol and search strategy, carried out consistency checks on document screening and coding, developed and refined the programme theory and CMOCs and revised the final report. CW reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Higher Education Funding Council for Wales funding for PRIME Centre Wales, Wales School for Social Prescribing Research, and the Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Project Advisory Group, and the students and staff at Wrexham Glyndwr University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Social Prescribing Network. Report of the Annual Social Prescribing Network Conference. Pontypridd: University of South Wales (2016).

2.

Torjesen I . Social Prescribing Could Help Alleviate Pressure on GPs. BMJ (2016) 352:i1436. 10.1136/bmj.i1436

3.

Polley M Bertotti M Kimberlee R Pilkington K Refsum C . A Review of the Evidence Assessing Impact of Social Prescribing on Healthcare Demands and Cost Implications. London: University of Westminster (2017).

4.

Johnson S Dalton-Locke C Vera San Juan N Foye U Oram S Papamichail A et al Impact on Mental Health Care and on Mental Health Service Users of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Methods Survey of UK Mental Health Care Staff. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2021) 56(1):25–37. 10.1007/s00127-020-01927-4

5.

O'Connor RC Wetherall K Cleare S McClelland H Melson AJ Niedzwiedz CL et al Mental Health and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Analyses of Adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing Study. Br J Psychiatry (2020) 218(6):1–8.

6.

NHS. NHS Long Term Plan. London: National Health Service (2019).

7.

Welsh Government. A Healthier Wales: Our Plan for Health and Social Care. Cardiff: Welsh Government (2018).

8.

DDCMS. A Connected Socety: A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness - Laying the Foundations for Change. London: Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (2018).

9.

Morse DF Sandhu S Mulligan K Tierney S Polley M Chiva Giurca B et al Global Developments in Social Prescribing. BMJ Glob Health (2022) 7(5):e008524. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008524

10.

Husk K Blockley K Lovell R Bethel A Lang I Byng R et al What Approaches to Social Prescribing Work, for Whom, and in What Circumstances? A Realist Review. Health Soc Care Community (2020) 28(2):309–24. 10.1111/hsc.12839

11.

Tierney S Wong G Roberts N Boylan AM Park S Abrams R et al Supporting Social Prescribing in Primary Care by Linking People to Local Assets: A Realist Review. BMC Med (2020) 18(1):49. 10.1186/s12916-020-1510-7

12.

Kimberlee R . What Is Social Prescribing?Adv Soc Sci Res J (2015) 2(1). 10.14738/assrj.21.808

13.

Chatterjee HJ Camic PM Lockyer B Thomson LJM . Non-Clinical Community Interventions: A Systematised Review of Social Prescribing Schemes. Arts Health Int J Res Pol Pract (2018) 10(2):97–123. 10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002

14.

Carnes D Sohanpal R Frostick C Hull S Mathur R Netuveli G et al The Impact of a Social Prescribing Service on Patients in Primary Care: A Mixed Methods Evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res (2017) 17:835–9. 10.1186/s12913-017-2778-y

15.

Frostick C Bertotti M . The Frontline of Social Prescribing - How Do We Ensure Link Workers Can Work Safely and Effectively Within Primary Care?Chronic Illn (2019) 17(4):404–15. 10.1177/1742395319882068

16.

Bird EL Biddle MSY Powell JE . General Practice Referral of 'at Risk' Populations to Community Leisure Services: Applying the RE-AIM Framework to Evaluate the Impact of a Community-Based Physical Activity Programme for Inactive Adults With Long-Term Conditions. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):1308. 10.1186/s12889-019-7701-5

17.

Kellezi B Wakefield JRH Stevenson C McNamara N Mair E Bowe M et al The Social Cure of Social Prescribing: A Mixed-Methods Study on the Benefits of Social Connectedness on Quality and Effectiveness of Care Provision. BMJ open (2019) 9(11):e033137. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033137

18.

Loftus AM McCauley F McCarron MO . Impact of Social Prescribing on General Practice Workload and Polypharmacy. Public Health (2017) 148:96–101. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.03.010

19.

Poulos RG Marwood S Harkin D Opher S Clift S Cole AMD et al Arts on Prescription for Community-Dwelling Older People With a Range of Health and Wellness Needs. Health Soc Care Community (2019) 27(2):483–92. 10.1111/hsc.12669

20.

Vogelpoel N Jarrold K . Social Prescription and the Role of Participatory Arts Programmes for Older People With Sensory Impairments. J Integrated Care (2014) 22(2):39–50. 10.1108/jica-01-2014-0002

21.

Blackman T What Affects Student Wellbeing? Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute (2020).

22.

NICE. Clinical Knowedge Summaries: Mental Health in Students. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020).

23.

GuildHE. Wellbeing in Higher Education. London: GuildHE (2018).

24.

Randstad A . Degree of Uncertainty: Student Wellbeing in Higher Education. London: Randstad (2020).

25.

Universities UK. Minding Our Futures: Starting a Conversation About the Support of Student Mental Health (2018).

26.

Elmer T Mepham K Stadtfeld C . Students Under Lockdown: Comparisons of Students' Social Networks and Mental Health Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One (2020) 15(7):e0236337. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

27.

Lopez-Valenciano A Suarez-Iglesias D Sanchez-Lastra MA Ayan C . Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students' Physical Activity Levels: An Early Systematic Review. Front Psychol (2020) 11(3787):624567. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.624567

28.

Savage MJ James R Magistro D Donaldson J Healy LC Nevill M et al Mental Health and Movement Behaviour During the COVID-19 Pandemic in UK University Students: Prospective Cohort Study. Ment Health Phys Activity (2020) 19:100357. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357

29.

Thorley T . Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities. London: Institute for Public Policy Research (2017).

30.

Baker H Ratnarajan G Harper RA Edgar DF Lawrenson JG . Effectiveness of UK Optometric Enhanced Eye Care Services: A Realist Review of the Literature. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt (2016) 36(5):545–57. 10.1111/opo.12312

31.

Pawson R Greenhalgh T Harvey G Walshe K . Realist Review-A New Method of Systematic Review Designed for Complex Policy Interventions. J Health Serv Res Pol (2005) 10(1):21–34. 10.1258/1355819054308530

32.

Wong G Westhorp G Pawson R Greenhalgh J . Realist Synthesis: RAMESES Training Materials. London: The RAMESES Project (2013).

33.

Lawson T . Economics and Reality. London: Routledge (1997).

34.

Pawson R . Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage (2006).

35.

Pawson R . The Science of Evaluation: A Realist Manifesto. London: SAGE (2013).

36.

Saul JE Willis CD Bitz J Best A . A Time-Responsive Tool for Informing Policy Making: Rapid Realist Review. Implement Sci (2013) 8(1):103. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-103

37.

University of Oxford. CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. University of Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Oxford: University of Oxford (2018).

38.

Pawson R Digging for Nuggets: How ‘Bad’ Research Can Yield ‘Good’ Evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2006) 9(2):127–42. 10.1080/13645570600595314

39.

Wong G Greenhalgh J Westhorp G Pawson R . Quality Standards for Realist Synthesis. Oxford: The RAMESES Project (2014).

40.

Pearson M Chilton R Wyatt K Abraham C Ford T Woods HB et al Implementing Health Promotion Programmes in Schools: A Realist Systematic Review of Research and Experience in the United Kingdom. Implement Sci (2015) 10:149. 10.1186/s13012-015-0338-6

41.

Peirce CS . Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce: Volumes I-VI. Harvard MA: Harvard University Press (1974).

42.

Greenhalgh T Pawson R Wong G Westhorp G Greenhalgh J Manzano A et al Retroduction in Realist Evaluation. Oxford: The RAMESES II Project (2017).

43.

Enrique A Mooney O Salamanca-Sanabria A Lee CT Farrell S Richards D . Assessing the Efficacy and Acceptability of an Internet-Delivered Intervention for Resilience Among College Students: A Pilot Randomised Control Trial Protocol. Internet Interv (2019) 17:100254. 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100254

44.

Stallman HM . Efficacy of the My Coping Plan Mobile Application in Reducing Distress: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Clin Psychol (2019) 23(3):206–12. 10.1111/cp.12185

45.

Webster NL Oyebode JR Jenkins C Bicknell S Smythe A . Using Technology to Support the Emotional and Social Well-Being of Nurses: A Scoping Review. J Adv Nurs (2020) 76(1):109–20. 10.1111/jan.14232

46.

Wiljer D Johnson A McDiarmid E Abi-Jaoude A Ferguson G Hollenberg E et al Thought Spot: Co-Creating Mental Health Solutions With Post-Secondary Students. Stud Health Technol Inform (2017) 234:370–5.

47.

Chandler GE Kalmakis KA Chiodo L Helling J . The Efficacy of a Resilience Intervention Among Diverse, At-Risk, College Athletes: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc (2020) 26(3):269–81. 10.1177/1078390319886923

48.

NICE. Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Mental Health in Students. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020).

49.

HEFCW. HE for a Healthy Nation: Student Wellbeing and Health. Cardiff: HEFCW (2019).

50.

Montagni I Tzourio C Cousin T Sagara JA Bada-Alonzi J Horgan A . Mental Health-Related Digital Use by University Students: A Systematic Review. Telemed J E Health (2020) 26(2):131–46. 10.1089/tmj.2018.0316

51.

Ray EC Arpan L Oehme K Perko A Clark J . Helping Students Cope With Adversity: The Influence of a Web-Based Intervention on Students' Self-Efficacy and Intentions to Use Wellness-Related Resources. J Am Coll Health (2019) 69:444–51. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1679818

52.

Thorley C . Not by Degrees: Improving Student Mental Health in the UK’s Universities. London: IPPR (2017).

53.

Wildman JM Moffatt S Penn L O'Brien N Steer M Hill C . Link Workers’ Perspectives on Factors Enabling and Preventing Client Engagement With Social Prescribing. Health Soc Care Community (2019) 27(4):991–8. 10.1111/hsc.12716

54.

Wallace C Elliott M Thomas S Davies-McIntosh E Beese S Roberts G et al Using Consensus Methods to Develop a Social Prescribing Learning Needs Framework for Practitioners in Wales. Perspect Public Health (2020) 141:136–48. 10.1177/1757913919897946

55.

Thomas SS . Top 10 Strategies for Bolstering Students' Mental Resilience. Chronicle Higher Edu (2009) 55(36).

56.

Byrom N . An Evaluation of a Peer Support Intervention for Student Mental Health. J Ment Health (2018) 27(3):240–6. 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437605

57.

Haas J Pamulapati LG Koenig RA Keel V Ogbonna KC Caldas LM . A Call to Action: Pharmacy Students as Leaders in Encouraging Physical Activity as a Coping Strategy to Combat Student Stress. Curr Pharm Teach Learn (2020) 12(5):489–92. 10.1016/j.cptl.2020.01.001

58.

Lattie EG Adkins EC Winquist N Stiles-Shields C Wafford QE Graham AK . Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res (2019) 21(7):e12869. 10.2196/12869

59.

Papadatou-Pastou M Campbell-Thompson L Barley E Haddad M Lafarge C McKeown E et al Exploring the Feasibility and Acceptability of the Contents, Design, and Functionalities of an Online Intervention Promoting Mental Health, Wellbeing, and Study Skills in Higher Education Students. Int J Ment Health Syst (2019) 13:51. 10.1186/s13033-019-0308-5

60.

Anderson S Fast J Keating N Eales J Chivers S Barnet D . Translating Knowledge: Promoting Health Through Intergenerational Community Arts Programming. Health Promot Pract (2017) 18(1):15–25. 10.1177/1524839915625037

61.

Bertotti M Frostick C Hutt P Sohanpal R Carnes D . A Realist Evaluation of Social Prescribing: An Exploration into the Context and Mechanisms Underpinning a Pathway Linking Primary Care With the Voluntary Sector. Prim Health Care Res Dev (2018) 19(3):232–45. 10.1017/S1463423617000706

62.

WHO. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: First International Conference on Health Promotion. Ottawa, Canada (1986).

63.