Abstract

Objective:

This scoping review aims to comprehensively map the existing literature on Patient Involvement (PI) in mental health education (MHE), identify the needs of mental health (MH) educators, students, and patients with lived experiences of MH challenges and develop a checklist for successful implementation of PI in MHE.

Methods:

Conducted between November 2023–January 2024, this review followed PRISMA-ScR guidelines in databases PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and WHO. Eligibility criteria adhered to PICOS guidelines, and screening was done via Covidence. Content analysis was carried out to develop a checklist.

Results:

Eleven qualitative articles were found, revealing two superordinate stakeholder needs categories: Interpersonal and Course Needs. Interpersonal Needs included Self-determination, Communication and Collaboration, Recognition and Support, and Holistic approach. Course Needs comprised Content, Organisational, and Teaching. A checklist was developed to support PI in MHE.

Conclusion:

Guidelines for successful PI in MHE should prioritize patient autonomy, foster collaboration, provide support, ensure inclusive course content, and promote patient involvement in educational processes. Study limitations, such as potential bias, underscore the need for future research to enhance evidence-based practices in MHE.

Introduction

Mental health education (MHE) is evolving to integrate the perspectives of individuals with firsthand mental health service (MHS) experience. This signifies a shift from a traditional passive role towards an active involvement of patients in students’ clinical education. In consonance with the findings of Simmons et al. and Costa et al. about individuals receiving mental health treatment, the word patient is used consistently throughout this review report and when an original article occupies a different name to indicate patients [1, 2]. This approach of Patient Involvement (PI) in MHE views mental health patients as experts by experience, (EBE) who contribute positively to students’ and EBE’s attitudes and wellbeing [3–5]. PI has historically received more attention in physical health education than in MHE [6]. In clinical and communication skills teaching, PI began in the late 1970s with role-play patients, evolving into symptomatic PI programs by the 1980s by Stillman to enhance medical student examination [7]. PI disappeared from clinical education but resurged with the shift to the biopsychosocial model, emphasising patient expertise and collaboration [8, 9].

According to the prevailing model of PI of Towle and colleagues, three guiding principles shape patient inclusion in teaching [9]. First, the knowledge patients possess by experience cannot be generated by faculty. Second, for authentic inclusion of patients, power relations should be balanced. Third, patients should have a say in how and what to teach. Towle et al. also propose a hierarchical structure or taxonomy of PI [9]. The taxonomy ranges from 1 (low participation) to 6 (high participation): wherein 1) the patient is studied as a case; 2) the patient volunteers in clinical tutorials; 3) the patient shares experiences within a pre-established module framework; 4) the patient is actively teaching and evaluating students; 5) the patient contributes to curriculum development; 6) the patient has sustainable membership within the educational institute. When patients do take an active role within the curriculum of MHE, patients mostly take on the role of teacher, taking up a lower-to intermediate-level of involvement [10].

From the health professionals’ perspective, barriers to more active PI in MHE include the view that patients may not be fit for collaboration in decision-making (often in the case of severe mental illness), a lack of conceptual clarity of PI, increasing demands on health professionals’ time, and the biomedical model’s tendency to focus on patient’s limitations rather than strengths [11]. Despite these perceived barriers, professionals from multiple MH fields are increasingly willing to involve PI in MHE programmes [4].

PI in healthcare education has different meanings depending on the stakeholder’s perspective. For this reason, an assessment of the benefits and shortcomings of PI within healthcare education is lacking [11]. This knowledge gap leaves MHE curriculum developers lacking predefined guidelines for implementing PI and, with this, limiting the potentially positive effects of PI by minimising its implementation in educational programmes [4, 11]. This also reflects the lack of consensus of the definition of PI in MHE [12].

While policymakers and MHS administrators may also have important roles to play in PI implementation, stakeholders such as students, educators, and patients are directly involved in the MHE process and have a profound impact on its outcomes. Identifying their needs is crucial for tailoring educational approaches to address specific challenges or enhance positive aspects of PI in MHE [13]. This information is needed to lay the groundwork for developing an evidence-based fundament for PI implementation within MHE and identify areas where understanding and utilising PI is still underexplored. This fundament can be used by curriculum developers, educators and policymakers to establish guidelines for successful PI implementation in MHE programmes. In short, this study aims to a) comprehensively map the existing literature on PI in MHE, b) systematically analyse and identify the needs of the three main stakeholders of PI in MHE, and c) develop a checklist based on these identified needs.

The following review question has been formulated using the PICOS framework to reach the previously mentioned benefits of conducting a scoping review [14].

“What are the needs of students, mental health professionals and patients in PI in MHE?.”

Methods

Scoping review was selected as the method due to the broad scope of the research topic and to highlight gaps in the existing literature to encourage future research in this dynamic and growing interdisciplinary field [15]. The scoping review protocol was based on established guidelines ([16], further refined by 15) and adheres to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [17]. This methodological framework and the prescribed reporting guideline aim to heighten the scoping review process’s replicability, and overall quality.

The literature research for this scoping review was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. For this literature review, PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and World Health Organization databases were systematically searched to ensure a comprehensive perspective on the literature. Both grey literature and peer-reviewed sources were explored to enhance data comprehensiveness, capturing a broader spectrum of specific PI-related experiences. This provides a more holistic view of PI, which aligns with the study’s goals [18]. The ProQuest Dissertations and Theses and World Health Organization search engines were used to identify literature sources not findable in scientific databases for this purpose.

The eligibility criteria in Table 1 were used to screen articles included in this scoping review. The screening process consisted of 2 phases: 1) title and abstract screening and 2) full-text screening, both undertaken by MK in consultation with YN. Criteria refinement was an iterative process informed by preliminary literature searches, with ongoing adjustments based on ambiguities during screening. Both review phases were conducted using the Covidence screening software [19]. A standardised data extraction form based on the PRISMA-ScR guidelines was used to capture the concepts of interest within each article [20]. Reference snowballing, using both forward and backward searches, was employed to extend the database searches.

TABLE 1

| Aspect | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Students, educators and patients who uptake an active role in MHE | Patients are not actively involved in education (level 1 or 2 in Towle et al. [9]’s taxonomy |

| Context and scope | PI in MHE is addressed | General healthcare education or pharmacy education |

| Outcomes | Focus on the needs of stakeholders concerning PI: exploration of practical implications and experiences of PI in MHE | No mention of implicit or explicit needs of students, patients or educators |

| Types of Evidence | Qualitative and quantitative studies, mixed-methods research, systematic reviews, grey literature, dissertations, conference abstracts/proceedings, case studies, study protocols, and professional organization reports | None |

Eligibility criteria (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

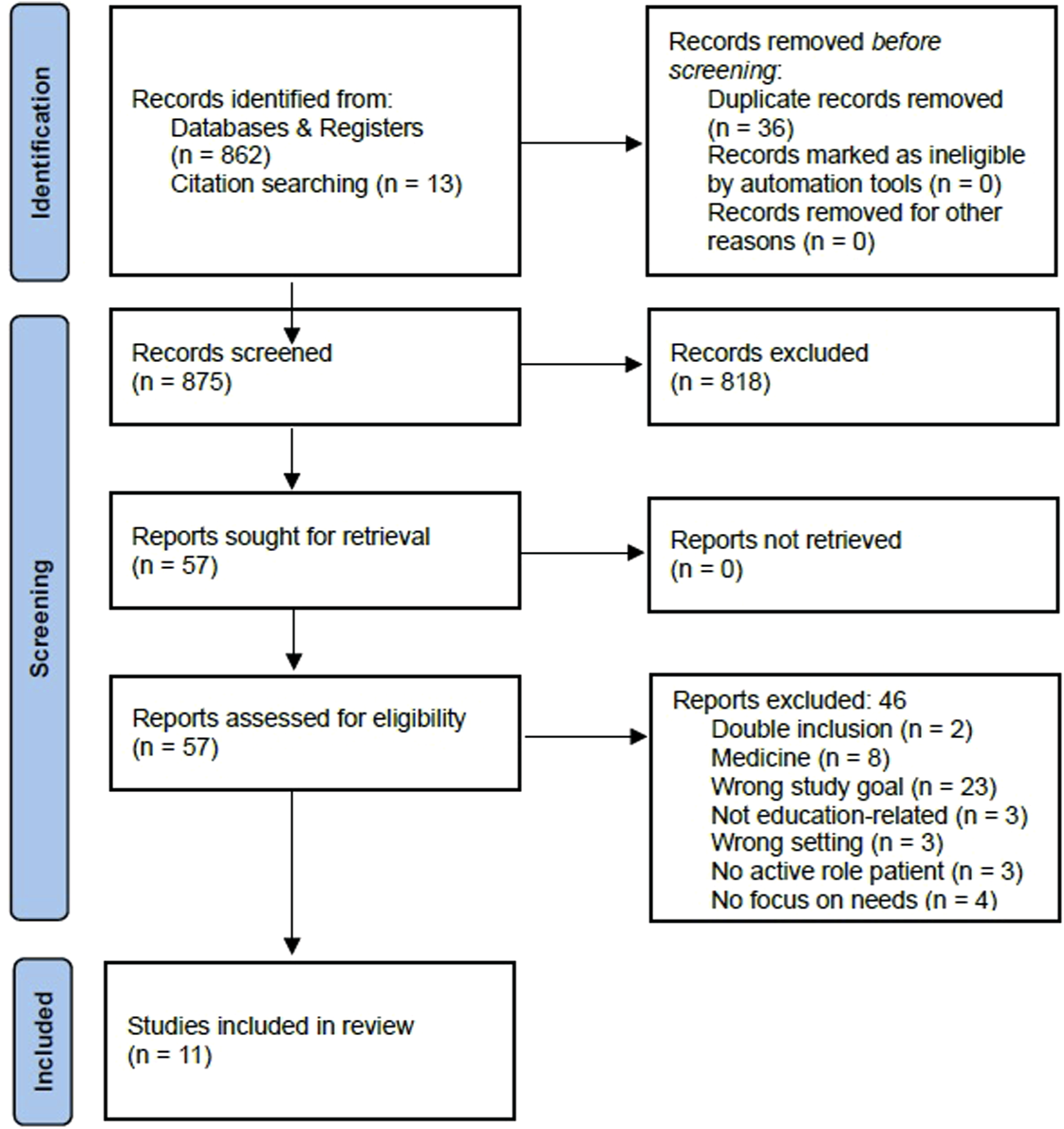

A pilot literature search by MK in PubMed established the initial keywords which were refined by YN. The search strategy (Table 2) included general search terms and specific search strings tailored for each database. PI in MHE encompasses various terms used for similar concepts, such as “patient involvement,” “consumer involvement,” and “service user involvement,” among others. Similarly, MHE spans diverse domains including clinical psychology, therapist training, and psychiatric nursing education. By formulating a search string that incorporates these terms and their synonyms, inclusivity and breadth is achieved. There were no predetermined restrictions on the studies’ publication date and geographic location, ensuring a thorough exploration of historical and contemporary literature. The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1, in which the number of excluded articles per step and the reason for exclusion are mentioned. The remaining articles were imported into the online study screening software Covidence [19].

TABLE 2

| Key words and boolean operators |

|---|

| (“patient involvement” OR “consumer involvement” OR “service user involvement” OR “expert* by experience” OR “lived experience” OR “mental health patient*” OR “mental health service user*” OR “mental health survivor*” OR “mental health consumer*” OR “psychiatric survivor*” OR “client involvement” OR “patient engagement” OR “EBE”) AND (“mental health education” OR “clinical psychology program*” OR “clinical psychology training” OR “clinical psychology curriculum” OR “psychology education” OR “psychology training” OR “psychology program*” OR “psychology curricul*” OR “psychology learning” OR “psychology teaching” OR “psychology student* perspective*” OR “therapist training” OR “therapist education” OR “therapist program*” OR “therapist curricul*” OR “Mental Health Training” OR “Psychology Education” OR “Mental Health Counseling” OR “Psychiatric Nursing Education” OR “Mental Health Professional Training” OR “Therapist Education” OR “Counseling Psychology Training” OR “Psychotherapy Training” OR “Community Mental Health Training” OR “Recovery-Oriented Training” OR “Mental Health Worker Training”) AND (“need*” OR “requirement*” OR “expectation*” OR “desire*” OR “necessit*”) |

Search string (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flowchart of study selection (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

The data charting form was developed within Covidence. Here, the study goal, the specific stakeholder that the article focuses on, the level of patient involvement (according to the model of Towle et al. [9]) and the identified needs for successful PI in MHE by the stakeholder education, were extracted from the articles. These categories were chosen to facilitate the comparison of data relevant for answering the research question. Data were gathered by reading the methods, results, and discussion sections of the 11 selected studies. The data extraction table is displayed in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Study ID | Participant Info |

Study objective | Stake-holder | Level of PI | Needs of investigated stakeholder(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell and Wilson [21] | 5 patients selected for participation Professional educators with >15 years of mental health service experience Ireland |

To explore the experiences of service users participating in a clinical psychology training course. The aim was to address limitations identified in previous research and supplement existing knowledge by employing IPA to understand the psychological processes involved in such initiatives | Patients | 2,3,4 | To be acknowledged as colleagues rather than subjects of study Educators and students value lived experiences over academic knowledge in contributing to the training of MH professionals Having power and influence Use of forum to express needs and views in a respectful atmosphere Transformation, both of self and the MH systems |

| Clarke et al. [22] | 10 randomly selected educators United Kingdom |

Review benefits and barriers to PI | Educators | Various active levels | Genuine and integral involvement rather than tokenistic approaches Importance of strategic involvement at the management level for effective change Integration of PI with other aspects of course Equality between stakeholders; colleague educators are open to new experiences Enough personal, financial resources and less bureaucracy in Universities. Enhance accessibility of course for individuals outside the MH field |

| Happell et al. [23] | Educator group (n = 34) Patient group (n = 12) Australia |

Present the perspectives and experiences of nurse academics and consumer educators regarding the feasibility and support for consumer participation roles in education for MH nursing | Educators and patients | Various active levels to ensure diversity | Reliability Need for organised and reliable patients Equality to general educational staff Vulnerability Recognise the burden on consumer and wellbeing issues and reduce tokenistic approach Patients that can handle vulnerability Support Systemic support and structured emotional support Seen as Griping Positive orientations are needed to gain a broader view Realistic and positive patients but not only those with ideas corresponding with views of academics |

| Happell et al. [24] | 51 students, 43 female, 8 male Finland, Australia, Ireland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway |

To gather and present student feedback regarding their experiences with Experts by Experience (EBE) in the context of mental health education | Students | 3,4 | More incorporated EBE-led sessions to enhance understanding of mental distress. Correct planning within schedule to maximise benefits of the programme Greater consistency between patient content and assessments More structure within the course programme Include multiple perspectives. More balanced presentation of positive and negative experiences from patients |

| Happell et al. [25] | 14 patients Finland, Australia, Ireland, Iceland, Netherlands, Norway |

To examine the experience of being an EBE from the perspective of EBEs involved in the design, development and delivery of an EBE-led mental health nursing module | Patients | 4,5 | Collaboration with and support from nursing educators Autonomy in presenting patient perspective and presenting views inconsistent with those of academics. Emotional and practical support by formal and informal support mechanisms, team meetings, help in navigating (digital) systems and open-door policies Establish and maintain boundaries in sharing personal stories. Be able to consider purpose of the narrative and be selective about the details shared Adapt to needs of individual students at different educational stages |

| Horgan et al. [37] | 50 patients participating in focus groups Iceland, Ireland, Finland, Netherlands, Norway and Australia |

To develop a learning module based on service users’ perspectives, experiences and opinions about service user involvement in mental health nursing education | Patients | Involved in teaching (n = 3) not further defined | Support; including external supervision, teamwork, and debriefing. Support for students who find working with patients distressing Facilitate emotional, communicational and personal developments of students by course. Practical content to aid holistic understanding of mental illness More than one patient involved in teaching: diverse range of experiences. Stories that balance positive and negative aspects of experience Longer periods of involvement spread over the years for deeper engagement and reflection |

| Kang et al. [26] | 98 psychiatry students at Semyung university, South Korea | To understand the impact of consumer involvement on nursing students’ attitudes towards mental health, their reflections on life, the learning experiences gained, and the preparation it provides for their future nursing careers | Students | 3 | Relating to lived experience to integrate theoretical knowledge and apply it More sessions with multiple patients, extended sessions and group discussions to improve own understanding More info about hospitalised consumers, more focus on nursing education and interaction with clinical experts in practice also to be integrated into the course |

| Kerry and Collett [27] | patient group of 10 + Group of 19 first-year trainee clinical psychologists in doctorate programme completing a survey United Kingdom |

To examine the level and impact of EbE involvement in teaching on a UK DClinPsych course. It sought to gather information to generate change ideas and recommendations for EbE involvement in teaching | Patients and students | 3, 4 | Patients Further training in teaching and utilising online platforms Emotional support in boundary-keeping and handling distressing challenges to feeling empowered in teaching Bring about changes in themselves, students and future clients. Bringing purpose to lived experiences. Students Relating to intimidating lived experiences to gain confidence More informal contact with patients, and opportunities to ask questions Balance of positive and negative presented experiences, hearing different views Early exposure to emotional content to optimise skills and knowledge Emotional support for distressing patient content. Time to reflect on presented experiences Hearing wide range of perspectives, more diversity in the patient population and presented experience |

| Lea et al. [28] | Focus group of 8 patients (4 men, 4 women) 5 clinical psychology trainees (4 women, 1 mam) 5 members of course staff (5 women) United Kingdom |

To elicit service users’, students’ and staff’s perceptions of the objectives and potential outcomes of service user involvement in clinical psychology training, in order to inform future questionnaire development | Patients, Educators, Students | 3 | Stay human through emotional intelligence development in educating students to ensure respectful future practice with cultural sensitivity Compassion for lived experience and emotional understanding, valuing lived experience more than academic knowledge Safe spaces to learn, learn from dealing with emotional experience and relating to it Learn how to instil meaning in life and self-determination; holistic approach (positive psychology approach). Reduction of the “them-us” divide Active role for patients in selection of the right patient for involvement Avoiding use of jargon |

| Meehan and Glover [29] | 95 patients (mean age = 47.2, 54% women) involved in teaching in the London medical school psychiatry course | Explore the experiences of former MH consumers who have participated in the education and training of MH staff and students | Patients | 4 | Prevention from feeling exposed by presenting lived experience; not being asked inappropriate questions or seen as practice doll for diagnosing Educators needs to value contribution of patients; prevention of tokenistic approach Patients want to know what is expected from them in educational programmes |

| Walters et al. [30] | 20 patients 12 educators 14 students All demographical diverse United Kingdom |

To evaluate the impact of patient involvement in undergraduate medical education, specifically in the context of teaching medical students in community settings, with a focus on patients with common mental disorders | Patients, Educators, Students | 3 | Students show sympathy for patient Patients need distress relief by debriefing and prevention of intrusive questions by students and educators Patients need solid boundaries to decrease the experienced increased obligation |

Data extraction table (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

To analyse the data, content analysis was employed to identify patterns and themes, as well as systematically categorise and synthesise the data [31]. Content analysis is particularly suitable for the exploratory nature of a scoping review, providing a foundational understanding of the topic, accommodating and conceptually mapping the diverse data available in the included studies [32]. The coding process, conducted in ATLAS.ti 23.4.0 for Windows, involved iterative refinement as more data were analysed. A trustworthiness checklist was followed to ensure analytical rigour [33].

Data analysis was conducted inductively to identify essential concepts and facilitate analysis and mapping [34]. In the preparation phase, the results sections of the 11 selected articles underwent probability sampling due to the large volume of text with low relevance to the analysis theme [34]. In the organisation phase, the coding process started with open coding to create categories and abstract the data. Then, axial coding was used to group similar concepts into new themes. Finally, selective coding was used to adjust and finalise the coding scheme, forming a general description of the main contents within the articles [35]. The analysis aimed to achieve thematic saturation, with further analysis unlikely to yield substantial new information or significantly alter identified content themes [36]. Coding guidelines were established to extract different stakeholders’ (patients, educators and students) implicit and explicit needs from the articles, enhancing research transparency and trustworthiness, as well as facilitating systematic data exploration (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Type of expressed need | Description of need | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Needs | Direct statements expressing needs. These are often straightforward and leave little room for interpretation | “A more equal relationship, not them thinking they are above you” [28] |

| Implicit Needs | Implicit needs may be implied or hinted at in the text. You may need to read between the lines to infer the needs of participants | “I’m waiting to see, that as I say our good faith in terms of how we’re involved and how we’re contributing is recognised.” [21]. |

| Descriptive Language | Indicates dissatisfaction or gaps, as these may point to underlying needs | “I think if there was too much kind of input or steering me in one direction that’s not giving authentic service user view” [25] |

| Expressed Preferences | Preferences indicate needs | “to learn more about the whole person, rather than the ill person they see in hospital or here in the services” [37] |

| Problem Statements | Problem statements point to opposing needs | “In one case this experience was attributed to a lack of sympathy of the student” [30] |

| Calls for Improvement | Indications for improvements or changes in existing programmes indicate unmet needs | “There could be more opportunity on placement for learning about service user perspectives and working with self-help/community groups’ [22] |

Guidelines for extracting needs from articles (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

Based on the results of the content analysis, a checklist was developed by YN and refined by EdB. An evidence-based checklist development approach was used, and refinement followed an expert-based approach [33, 38]. First the frequency of the codes was reviewed, then the themes and subthemes were re-interpreted based on the relevance to MHE.

Results

The inductive content analysis revealed two superordinate themes related to the needs of stakeholders concerning PI in MHE: interpersonal needs and course needs (see Table 5). The needs of patients, educators and students are presented holistically since many themes have relationships with two or all stakeholders in slightly different ways, although reporting the nature of the relationships was beyond the scope of our interpretive strategy. Most themes highlight the needs of patients since most research on PI in MHE is conducted on patients.

TABLE 5

| Superordinate theme | Subordinate theme | Individual codes |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Needs | Self-determination | Autonomy [21, 22, 25, 28] Being valued and recognised [21, 25, 27–29] Bring about change [21, 22, 25, 27, 28] Coming to terms with problems [30] Empowering patients [22, 25, 27, 28] Having hope [28] Learning to use own experiences [28] |

| Communication and collaboration | Collaboration with mental health institutes [26] Collaborative approach between stakeholders [22, 25–27, 30, 37] Equality between patients and educators [21, 27, 28] Openness to other views [22, 25, 27, 28] Relationship development [21, 23, 24, 30] Trust [22, 28] |

|

| Recognition and Support | Being ensured of employment [27] Companionship [21, 23] Debriefing [21, 23, 27, 28, 30] Emotional support [23, 25, 27, 37] Intellectual support [28, 37] Positive feedback or affirmation [21, 27] Practical support [23, 25, 27] Reduction of us-them thinking [22], [28] Relating to lived experience [22, 26–28] Take into account vulnerability [21, 23, 27, 29] |

|

| Holistic approach | Holistic view on patients [26, 28, 37] Humanising patients [26–29] Positive psychology viewpoint [28, 29] Purposefulness consideration of personal story [22, 25, 27, 30] Self-help or community involvement [22] |

|

| Course Needs | Content Needs | Applicable knowledge [26, 27] Balance positive and negative experiences [22, 24, 25, 27, 37] Communicating authentic stories [25, 37] Discussion of therapies [24, 26, 28] Diversity of presented experiences [22, 24, 27] Early exposure to emotional content [27] Focus on emotional intelligence enhancement [27, 28, 37] Incorporate content into assessments [24, 28] Information on mental health journey [27] Learning from uncomfortable teaching [28] More course content [22, 24, 26, 37] Prioritise EBE lessons in the course [22, 24] Promote understanding of mental distress by students [27, 28, 37] Promotion of understanding of broad influence mental health problems [27, 28, 37] Value lived experience above knowledge [26–29] |

| Organisational Needs | Address limitations by illness [23] Extend PI content outside of MH education [22, 24, 25, 37] Group discussion with all stakeholders [26–28] Information on mental health journey [27] Make PI course mandatory [24] More integration into the course [22, 22, 27–29] More interaction with students [21, 25, 26, 37] Need for continuous improvement [30] Online education opportunities [27] Practical and organisational resources [22] Prevention of tokenism [21–23, 29] Safe learning spaces to learn together [28] Time to reflect on PI content [25, 27, 37] Involve the right patient [28] |

|

| Teaching Needs | Adapting to student’s knowledge and experiences [25, 37] More interaction with students [21, 25, 26, 37] Avoiding the use of jargon [28] Training in teaching [22, 27, 29] Good communication skills [21, 28] Learning gains from uncomfortable teaching [28] |

Discovered themes of needs of stakeholders concerning PI in MHE (Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders for Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education, Netherlands, 2024).

Interpersonal Needs

The superordinate theme of Interpersonal Needs in the context of PI in MHE encompasses the interpersonal dynamics between patients, educators, and the broader educational system.

The subordinate category of Self-Determination depicts the need for autonomy, highlighting the importance of control within the educational contributions of patients. This autonomy extends to decisions regarding the content they share, how they share it, and the impact they hope to make [21, 22, 25, 28]. A quote from a patient from the research of Campbell et al. illustrates this: “I’m waiting to see, that as I say our good faith in terms of how we’re involved and how we’re contributing is recognised.” (p. 343). Patients seek influence in decision-making as well as feelings of empowerment after their involvement in the educational process, desiring a sense of capability and influence. Empowerment enables them to actively contribute to the educational process and contribute to a positive impact on MHE [25].

Another subordinate category of Interpersonal Needs is Communication and Collaboration between patients and educators (and MHE institutions). Clear communication of shared goals and vision for MHE is often seen as crucial by all stakeholders. This is underscored multiple times by patients’ desire to be seen as equal to educators within the educational process [21, 27, 28]. This equality involves ensuring that patients’ voices, perspectives, and lessons are treated equally to those of educators and MH professionals, which students also acknowledge as necessary. As a student pointed out in Lea et al. [28], “A more equal relationship, not them thinking they are above you” (p. 6). This requires a dialogue that values the input of both parties, and entails acknowledging patients’ expertise and recognising that effective collaboration relies on a reciprocal exchange of trust and understanding [22]. Also, fostering positive relationships between patients, educators, and MH professionals is emphasised. Building trust and rapport creates a conducive environment for effective collaboration, enabling sharing of experiences and knowledge in a respectful environment [21, 23, 24, 30].

A third subordinate category of Interpersonal Needs is Recognition and Support for PI in MHE, which relates to an often-perceived lack of support for all stakeholders within the educational field. Lived experiences presented by patients may be distressing for all stakeholders, emphasising a need for emotional support opportunities [23, 25, 27, 28, 37]. A proposed way of providing emotional support was to have more time after educational sessions for patients to talk about the lesson and to support each other, as pointed out by students in the research of Horgan [37]. Intellectual support complements this by fostering the intellectual growth of all stakeholders through the lessons taught by patients, ensuring that their contributions are both emotionally validated and intellectually stimulating. Practical support includes assistance in navigating the practical aspects of the course, such as educational systems and software [37]. Stakeholders express a desire for positive feedback and affirmation, depicting the need for explicit recognition of patients’ efforts by both students and educators [21, 27]. Patients’ need for authentic connections with students and educators underscores the importance of valuing personal backgrounds in patient education, fostering empathy and understanding among learners and educators [22, 26–28]. The reduction of us-them thinking centres on breaking down binary distinctions and fostering a sense of shared identity and collaboration. In the context of patient educators, this means dismantling perceived divisions between educators, learners, and individuals with lived experiences [22, 28]. An example of this is the perspective of a patient pointed out by Clarke and Holttum [22]: “It helps develop a different mindset for the trainee (student) - experiencing the other differently but not ‘othering’.” (p. 5).

The final subordinate category of Interpersonal Needs is Holistic Approach, which includes acknowledging patients as multifaceted individuals, recognising the interconnectedness of their lives beyond MH issues [26–28, 37]. The purposeful consideration of personal stories involves recognising the power of narrative in MHE [22, 25, 27, 28, 30]. In the research by Lea et al. and Meehan et al., there is a recurrent theme of needs, emphasizing a positive psychology viewpoint [28, 29]. This viewpoint underscores strengths, resilience, and wellbeing, and thus departs from deficit-focused approaches to one that highlights the strengths of patients in PI in MHE.

Course Needs

The superordinate Course Needs theme encompasses a commitment to providing a comprehensive, relevant, and empathetic educational experience for students, educators, and patients. The subordinate theme Content theme addresses requirements for MHE content, including relevance, balancing positive and negative experiences, authentic storytelling, and therapeutic approaches. When during teaching patients share both successful treatment elements and negative experiences, this can positively impact MHE [22–25, 27, 37]. The quotes of a patient and a student in the research of Kerry et al. illustrate this vividly [27]. Patient: “I hoped that, by discussing good and bad experiences, we could influence future outcomes for clients in a similar position to us.” Student: “I also found it helpful to hear some of their more negative experiences of services, as I have tried to bear those in mind and avoid similar practice on placement.” (p.4). Also, students emphasize the importance of diversity (various life experiences, cultural backgrounds, and cognitive perspectives beyond the neurotypical) in the patient population and lived experiences [22–24, 27]. An example of this is pointed out by a student in Kerry et al.’s research: “it would have been substantially helpful to hear from individuals with lived experience who may not quite fit specific diagnostic criteria, or who may have had alternative reflections on diagnoses.” (p.7) [27]. Furthermore, stakeholders stressed the need for expanded course content and increased integration of patient-led lessons into the curriculum, alongside mandatory PI courses for MH students. This highlights the importance of prioritising PI in MHE beyond current practices. Patients should not merely share their stories as an adjunct to the course; rather, their educational contributions should be seamlessly integrated into the broader curriculum and assessment methods [22–25, 27–29].

The subordinate theme Organisational Needs reflects the acknowledgement of specific requirements and considerations needed for successful PI courses at the organisational level. It encompasses how the courses with PI need to be planned, organised, and shaped, such as planning enough time to reflect on PI content and enhancing the integration of the PI content into an overarching course. Prevention of tokenism is a critical aspect of the organisational needs and relates to the subordinate category of Interpersonal Need to be recognised and supported as a patient educator. Tokenism occurs when individuals from underrepresented groups are included merely to give the appearance of diversity without truly valuing their contributions [39]. The course has to prevent a tokenistic approach to enable the interpersonal needs discussed above. Thoughtful selection of patients should align their experiences with learning objectives, fostering meaningful contributions and should be selected (by patient educators) based on these requirements [21–23, 29].

The subordinate theme Teaching Needs encompasses requirements for impactful learning. This involves adapting teaching methods to suit diverse student experiences and promoting active engagement and collaborative learning. Patients should possess adequate communication skills for teaching [28]. Stakeholders also advocate for PI in the selection of educators to maintain group momentum [21]. Furthermore, training in teaching is pointed out as essential. Acknowledging the value of uncomfortable teaching experiences fosters personal growth, encouraging the navigation of challenging situations and reconsidering assumptions [28].

A Comprehensive Checklist for Implementing PI in MHE

Based on the findings described above (also see Table 5), we developed a checklist (see Supplementary Material) for potential stakeholders to incorporate more frequent and more active PI in MHE. This checklist can serve as an evidence-based starting point for educators and curriculum developers in MHE to expand and assess PI in MHE. The checklist is compiled with the two main themes, and their subthemes that emerged from the review as described above: Interpersonal Needs consisting of Self-determination, Communication and Collaboration, Recognition and Support, and Holistic approach, and Course Needs consisting of Content, Organisational, and Teaching. For each theme, a comprehensive list of questions is provided that ensures a thorough check of all aspects of implementing or augmenting PI in MHE. This is the first comprehensive checklist for implementing PI in MHE based on a comprehensive literature review.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to comprehensively map the existing literature on PI in MHE and analyse and identify the needs of MH educators, students, and patients with lived experiences of MH challenges and develop a checklist for successful implementation of PI in MHE. This scoping review contributes to the field by providing a preliminary map of evidence and providing a checklist for stakeholders aiming to incorporate PI in their MHE programmes.

Implications for MHE

The primary research questions, focusing on the needs of stakeholders in MHE, were addressed by an inductive content analysis and revealed two superordinate themes. These are Interpersonal Needs, consisting of the subordinate themes of Self-determination, Communication and Collaboration, Recognition and Support and a Holistic Approach, and Course Needs, consisting of Content Needs, Organisational Needs and Teaching Needs. Based on these themes, our checklist for successful PI in (MHE) emphasises patient autonomy, collaboration, and communication among all stakeholders with mutual respect and equality. Providing emotional and intellectual support for all parties, along with practical assistance for patients, is crucial. Additionally, adopting a positive psychology perspective that portrays patients as multidimensional individuals beyond their symptoms (see e.g., [40]) is essential for fostering positive interpersonal relations. In terms of the course, guidelines should focus on creating balanced and inclusive content that integrates patient stories effectively. Patients should also receive training for teaching and play an active role in selecting suitable candidates for MHE.

Implications for Research

The literature on PI in MHE reveals several gaps that need further research. There is a lack of standardised methods in research on PI in MHE, hindering the reliability of findings in this field. Standardised methods and consistent procedures could fill this gap.

The contextual variations present within different programmes and institutions in MHE are not adequately researched and thus present one of the literature gaps. For example, MH nursing and psychiatry involve medically schooled students and educators. Both disciplines fall between the social sciences and medical sciences, taking a different stance than clinical psychology students and educators who are social scientists [41]. Consequently, it becomes crucial for research efforts to not only acknowledge these contextual nuances but also actively seek to identify and address the specific challenges and opportunities they present. For instance, a PI intervention that proves successful in one psychiatric or MH training program may encounter obstacles or require modifications when implemented in a clinical psychology curriculum. Understanding these differences is necessary for tailoring PI strategies to suit the needs of each educational context, ultimately heightening the effectiveness of PI initiatives across various fields within MHE. Important criteria for developing these guidelines could be e.g., the relevance of the course content and assessment criteria to the specific educational needs per field. Our checklist is a preliminary attempt, yet more comprehensive guidelines need further research. Interpersonal needs criteria that may be researched are the possible differences in communication and collaboration between stakeholders in the field. Research on the differences between stakeholder needs in various fields of MH could include a programme-specific needs assessment and a qualitative exploration of stakeholder needs. After this, future research could explore strategies to adapt PI initiatives to meet the specific needs of different MHE programmes to tackle programme-specific challenges.

In this scoping review, PI mainly centred on presenting patients’ own lived experiences. Patients at higher levels of involvement (level 5 or 6 according to Towle et al.) are expected to express less desire for further involvement, empowerment, autonomy, and collaborative approaches, as these aspects are fundamental to their active educational role. Further research is needed to explore the needs of patients at different levels of Towle et al.’s taxonomy. Nonetheless, we recognise that since cutoff of our search, more studies with focus on PI in MHE have been published [42], including a qualitative systematic review, albeit with a different focus [43]. We acknowledge that we are situated in a dynamic research field and that there is the need for regular and rapid reviews to synthesize the knowledge produced in this emerging arena.

Limitations of the Study

One limitation of the current study is the subjective nature of the inductive content analysis and checklist development, wherein implicit references were extracted to uncover stakeholders’ underlying needs. The initial review and data analysis process relied for a large part on the perspective of MK who was inherently involved in PI in MHE as a clinical psychology intern at the time of data analysis. Additionally, supervision and checklist development were undertaken by YN and EdB, clinical psychology practitioners, researchers and educators, who are themselves stakeholders. This positionality underscores the potential for bias in extracting and synthesising information, as individual perspectives may influence the identification and interpretation of stakeholders’ needs [44]. To address this, future research could validate these findings through qualitative studies guided by the same research question, involving multiple researchers [45].

The absence of a quality assessment of the included studies, due to scoping nature of the review, constitutes another limitation. This absence of methodological evaluation may have led to the inclusion of methodologically flawed studies, potentially impacting the overall reliability of the findings. This limitation underscores the need for caution in generalising the identified needs, as the quality and validity of the included studies were not systematically appraised, and furthermore underscores the need for studies in this field with a sound methodological approach.

Furthermore, the analytical strategy employed in this study did not permit interpreting the interconnectedness of relationship between the needs of the different stakeholders. The relational nature of education, especially professional education, implies that the needs of one stakeholder is inherently connected to the needs of another. Additionally, due to the power differentials within the hierarchical structure of MHE, one stakeholder may be responsible for meeting the needs of the other. A full relational analysis was beyond the scope of this study. Future research studies could employ analytical approaches such as Situational Analysis to allow for a more comprehensive relational and positional analysis [46].

Lastly, there is a possibility that publications were not captured although efforts were made to include a diverse range of databases. The inclusion criteria also focused on English-language studies, potentially leading to the exclusion of relevant non-English literature that could provide valuable cross-cultural insights. This is likely, considering the high inclusion of UK, Ireland, and Australia studies. The overrepresentation of research from the Happell et al. group suggests potential publication bias. To enhance understanding, future research should include diverse patient perspectives from additional countries and cultures. Comparative studies examining caregivers’ viewpoints can also contribute to a comprehensive understanding of PI [47].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on PI in MHE and identifies the needs of stakeholders, including students, MH professionals, and patients with lived experiences for successful PI implementation in MHE. Through an inductive content analysis, two overarching themes emerged: Interpersonal Needs and Course Needs, each comprising several subordinate themes. A checklist was constructed based on the content analysis findings. These offer valuable insights and practical tools for curriculum developers, educators, policymakers, and researchers, laying the groundwork for evidence-based guidelines to enhance PI in MHE. Addressing the identified gaps, such as standardising research methods, understanding contextual variations across MHE programs, and including diverse patient perspectives, presents opportunities for future research and practice in this area. Despite limitations, including the subjective nature of the analysis and potential publication bias, this study’s comprehensive approach contributes to advancing our understanding of PI in MHE and underscores the importance of collaborative efforts to promote patient-centred education and practice in mental health.

Statements

Author contributions

YN and MK shaped the research question. MK and YN were responsible for the design and conceptualisation of the review. EB significantly contributed to the conceptualisation. MK conducted the search and screening. MK drafted the initial manuscript. YN and EB revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2025.1608124/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Simmons P Hawley CJ Gale TM Sivakumaran T . Service User, Patient, Client, User or Survivor: Describing Recipients of Mental Health Services. Psychiatrist (2010) 34(1):20–3. 10.1192/pb.bp.109.025247

2.

Costa DSJ Mercieca-Bebber R Tesson S Seidler Z Lopez AL . Patient, Client, Consumer, Survivor or Other Alternatives? A Scoping Review of Preferred Terms for Labelling Individuals Who Access Healthcare across Settings. BMJ Open (2019) 9(3):e025166. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025166

3.

Arblaster K Mackenzie L Willis K . Mental Health Consumer Participation in Education: A Structured Literature Review. Aus Occup Ther J (2015) 62(5):341–62. 10.1111/1440-1630.12205

4.

Happell B Donovan AO Warner T Sharrock J Gordon S . Creating or Taking Opportunity: Strategies for Implementing Expert by Experience Positions in Mental Health Academia. Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2022) 29(4):592–602. 10.1111/jpm.12839

5.

Namer Y Drüke F Razum O . Transformative Encounters: A Narrative Review of Involving People Living With HIV/AIDS in Public Health Teaching. Public Health Rev (2022) 43:1604570. 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604570

6.

Adam HL . A Personal Perspective on Patient Involvement in Educating Health Care Providers: From Two Lenses. J Patient Experience (2021) 8:2374373521996959. 10.1177/2374373521996959

7.

Stillman PL Ruggill JS Rutala PJ Sabers DL . Patient Instructors as Teachers and Evaluators. Acad Med (1980) 55(3):186–93. 10.1097/00001888-198003000-00005

8.

Halabi IO Scholtes B Voz B Gillain N Durieux N Odero A et al “Patient Participation” and Related Concepts: A Scoping Review on Their Dimensional Composition. Patient Education Couns (2020) 103(1):5–14. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.001

9.

Towle A Bainbridge L Godolphin W Katz A Kline C Lown B et al Active Patient Involvement in the Education of Health Professionals. Med Education (2010) 44(1):64–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x

10.

Dijk SW Duijzer EJ Wienold M . Role of Active Patient Involvement in Undergraduate Medical Education: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open (2020) 10(7):e037217. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037217

11.

Jørgensen K Rendtorff JD . Patient Participation in Mental Health Care – Perspectives of Healthcare Professionals: An Integrative Review. Scand Caring Sci (2018) 32(2):490–501. 10.1111/scs.12531

12.

Tambuyzer E Pieters G Van Audenhove C . Patient Involvement in Mental Health Care: One Size Does Not Fit All. Health Expect (2014) 17(1):138–50. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00743.x

13.

Khalil AI Hantira NY Alnajjar HA . The Effect of Simulation Training on Enhancing Nursing Students’ Perceptions to Incorporate Patients’ Families into Treatment Plans: A Randomized Experimental Study. Cureus (2023) 15:e44152. 10.7759/cureus.44152

14.

Thomas J Kneale D McKenzie JE Brennan SE Bhaumik S et al Determining the Scope of the Review and the Questions It Will Address. In: HigginsJPTThomasJChandlerJCumpstonMLiTPageMJ, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 1st ed. Wiley (2019). p. 13–31. 10.1002/9781119536604.ch2

15.

Arksey H O’Malley L . Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Social Res Methodol (2005) 8(1):19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616

16.

Levac D Colquhoun H O’Brien KK . Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implementation Sci (2010) 5(1):69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

17.

Tricco AC Lillie E Zarin W O’Brien KK Colquhoun H Levac D et al PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med (2018) 169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850

18.

Benzies KM Premji S Hayden KA Serrett K . State-Of-The-Evidence Reviews: Advantages and Challenges of Including Grey Literature. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs (2006) 3(2):55–61. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x

19.

Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence - Better Systematic Review Management (2023). Available from: https://www.covidence.org/ (Accessed October 29, 2024).

20.

Page MJ Moher D Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 372:n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160

21.

Campbell M Wilson C . Service Users’ Experiences of Participation in Clinical Psychology Training. JMHTEP (2017) 12(6):337–49. 10.1108/jmhtep-03-2017-0018

22.

Clarke SP Holttum S . Staff Perspectives of Service User Involvement on Two Clinical Psychology Training Courses. Psychol Learn and Teach (2013) 12(1):32–43. 10.2304/plat.2013.12.1.32

23.

Happell B Bennetts W Platania‐Phung C Tohotoa J . Consumer Involvement in Mental Health Education for Health Professionals: Feasibility and Support for the Role. J Clin Nurs (2015) 24(23–24):3584–93. 10.1111/jocn.12957

24.

Happell B Waks S Horgan A Greaney S Bocking J Manning F et al Expert by Experience Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: Nursing Students’ Perspectives on Potential Improvements. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2019) 40(12):1026–33. 10.1080/01612840.2019.1631417

25.

Happell B Warner T Waks S O’Donovan A Manning F Doody R et al Becoming an Expert by Experience: Benefits and Challenges of Educating Mental Health Nursing Students. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2021) 42(12):1095–103. 10.1080/01612840.2021.1931583

26.

Kang KI Shin S Joung J . Consumer Involvement in Psychiatric Nursing Education: An Analysis of South Korean Students’ Experiences. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2023) 44(5):418–24. 10.1080/01612840.2023.2194992

27.

Kerry E Collett N Gunn J . The Impact of Expert by Experience Involvement in Teaching in a DClinPsych Programme; for Trainees and Experts by Experience. Health Expect (2023) 26(5):2098–108. 10.1111/hex.13817

28.

Lea L Holttum S Cooke A Riley L . Aims for Service User Involvement in Mental Health Training: Staying Human. JMHTEP (2016) 11(4):208–19. 10.1108/jmhtep-01-2016-0008

29.

Meehan T Glover H . Telling Our Story: Consumer Perceptions of Their Role in Mental Health Education. Psychiatr Rehabil J (2007) 31(2):152–4. 10.2975/31.2.2007.152.154

30.

Walters K Buszewicz M Russell J Humphrey C . Teaching as Therapy: Cross Sectional and Qualitative Evaluation of Patients’ Experiences of Undergraduate Psychiatry Teaching in the Community. BMJ (2003) 326(7392):740. 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.740

31.

Hsieh HF Shannon SE . Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res (2005) 15(9):1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687

32.

Elo S Kyngäs H . The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J Adv Nurs (2008) 62(1):107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

33.

Elo S Kääriäinen M Kanste O Pölkki T Utriainen K Kyngäs H . Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness. Sage Open (2014) 4(1):2158244014522633. 10.1177/2158244014522633

34.

Kyngäs H . Inductive Content Analysis. In: KyngäsHMikkonenKKääriäinenM, editors. The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 13–21. 10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6_2

35.

Williams M Moser T . The Art of Coding and Thematic Exploration in Qualitative Research. Int Manag Rev (2019) 15(1):45–72.

36.

Saunders B Sim J Kingstone T Baker S Waterfield J Bartlam B et al Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual Quant (2018) 52(4):1893–907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

37.

Horgan A Manning F Donovan MO Doody R Savage E Bradley SK et al Expert by Experience Involvement in Mental Health Nursing Education: The Co‐Production of Standards Between Experts by Experience and Academics in Mental Health Nursing. Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2020) 27(5):553–62. 10.1111/jpm.12605

38.

Hettinga AM Denessen E Postma CT . Checking the Checklist: A Content Analysis of Expert- and Evidence-Based Case-Specific Checklist Items: Content Analysis of Checklist Items. Med Education (2010) 44(9):874–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03721.x

39.

Linkov V . Tokenism in Psychology: Standing on the Shoulders of Small Boys. Integr Psych Behav (2014) 48(2):143–60. 10.1007/s12124-014-9266-2

40.

Westerhof GJ Keyes CLM . Mental Illness and Mental Health: The Two Continua Model Across the Lifespan. J Adult Dev (2010) 17(2):110–9. 10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y

41.

Singh A Singh S . Psychiatrists and Clinical Psychologists. Mens Sana Monogr (2006) 4(1):10–3. 10.4103/0973-1229.27599

42.

Bradley SK Fowley A McDonald D Norton M Sulej M Smyth S . Embedding Service User Experience (‘Experts by Experience’) into Undergraduate Mental Health Nursing Education: A Co‐Production Research Project. Int J Ment Health Nurs (2025) 34(1):e13500. 10.1111/inm.13500

43.

Stanyon M Ryan K Dilks J Hartshorn K Ingley P Kumar B et al Impact of Involvement in Mental Health Professional Education on Patient Educators: A Qualitative Systematic Review. BMJ Open (2024) 14(2):e084314. 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084314

44.

Willig C . Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology: Adventures in Theory and Method. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open university press (2008).

45.

Michalos AC , editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (2014). 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5

46.

Clarke AE Friese C Washburn R . Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Interpretive Turn. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE (2018). p. 426.

47.

Dalton JE Bolen SD Mascha EJ . Publication Bias: The Elephant in the Review. Anesth and Analgesia (2016) 123(4):812–3. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001596

Summary

Keywords

patient involvement, mental health education, scoping reviews, checklist, content analysis

Citation

Klarenbeek M, de Bruin E and Namer Y (2025) Exploring the Needs of Stakeholders For Successful Patient Involvement in Mental Health Education. Public Health Rev. 46:1608124. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2025.1608124

Received

01 November 2024

Accepted

11 February 2025

Published

12 March 2025

Volume

46 - 2025

Edited by

Katarzyna Czabanowska, Maastricht University, Netherlands

Reviewed by

Ana Cruz, University of Porto, Portugal

One reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Klarenbeek, de Bruin and Namer.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Yudit Namer, y.namer@utwente.nl

This Review is part of the PHR Special Issue “Transformative Public Health Education”

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.