Abstract

Objectives:

The following scoping review aims to identify and map the existing evidence for HIT interventions among women with DV experiences in the United States. And provide guidance for future research, and facilitate clinical and technical applications for healthcare professionals.

Methods:

Five databases, PubMed, EBSCOhost CINAHL, Ovid APA PsycINFO, Scopus and Google Scholar, were searched from date of inception to May 2023. Reviewers extracted classification of the intervention, descriptive details, and intervention outcomes, including physical safety, psychological, and technical outcomes, based on representations in the included studies.

Results:

A total of 24 studies were included, identifying seven web-based interventions and four types of abuse. A total of five studies reported safety outcomes related to physical health. Three studies reported depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder as psychological health outcomes. The effectiveness of technology interventions was assessed in eight studies.

Conclusion:

Domestic violence is a major public health issue, and research has demonstrated the tremendous potential of health information technology, the use of which can support individuals, families, and communities of domestic violence survivors.

Introduction

Domestic violence (DV) is a significant yet frequently underreported public health concern that menaces individuals’ physical and mental wellbeing globally [1]. As defined by the United States (U.S.) Office on Violence against Women, DV encompasses a pattern of abusive behavior within any intimate relationship that one partner uses to sustain or maintain control over another partner [2]. An array of abuse that could happen within a household includes physical, psychological, sexual, and financial towards the children, elderly, or intimate partner [2]. One in three women encounters physical violence from an intimate partner every minute, resulting in approximately 10 million abuse survivors annually in the U.S. [3]. Moreover, DV exerts a significant financial burden with an estimated cost of $103,767 per female affected by intimate partner violence (IPV) [4].

Compared to men, women exhibit a significantly elevated vulnerability to experiencing DV in a lifetime [5]. Persistent experience of DV is associated with an array of detrimental effects on physical and mental health, including hypertension, diabetes [6], depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [7–9], AIDS/HIV infection [10], sleep disturbances [11], and suicide attempts [12]. Nevertheless, the profound impact of DV on women is often underestimated due to its intricate nature, the prevalence of revictimization, and intergenerational victimization [13].

Intervention studies are pivotal in empowering survivors to overcome their challenges and enhancing their physical and mental wellbeing. However, conducting studies involving women with DV experiences often encountered substantial challenges. Previous research highlighted the difficulties faced when approaching DV survivors in person due to societal stigma, shame, guilt, alienation, and judgment [14–16]. Traditional intervention methods such as focus group, one-to-one in-person interviews, and individual/group therapy require substantial time for participants’ recruitment and are susceptible to confidentiality issues among participants. Recently, health information technology (HIT) has been gaining traction in DV research, such as developing more precise and effective screening tools and improving the overall wellbeing for DV survivors. HIT refers to the utilization and application of information processing that includes both computer hardware and software, across the spectrum of data storing, retrieving, sharing, and using healthcare information, health-related data from both patients or healthcare providers, and knowledge for effective healthcare communication and decision-making in certain disease journey [17]. HIT interventions (e.g., guided online support) offer an anonymous environment that allows survivors to access information and seek help without the time and location constraints [18]. Women with DV experiences face additional vulnerabilities due to limited access to resources and the societal-asserted feminine duties on childcare and housework tasks. The use of HIT intervention allows these women to reach resources and seek help from the virtual space without restrictions. Also, studies indicated that women survivors tend to be more emotional and prefer text-based communication with healthcare providers as it provides them with a sense of anonymity and security [19].

With HIT accessible through mobile devices, women may easily acquire a wealth of health information and increase their likelihood of disclosing their abusive experience [20]. Studies also show the use of HIT interventions can improve health outcomes among the DV population. However, to the best of our knowledge, current reviews have only examined HIT interventions for mental health [21], child maltreatment [22], and peer aggression [23]. Although the application of HIT in the DV population has surged unprecedentedly, no evidence summarized the current state of the science of HIT interventions particularly in women with DV experiences.

As such, this scoping review aims to identify and map the available evidence for HIT interventions among women with DV experiences in the United States. This review can guide future research and advance the clinical and technological applications available to healthcare professionals.

Methods

Search Strategy

Four bibliographic databases were searched from date of inception to May 2023 (PubMed, EBSCOhost CINAHL, Ovid APA PsycINFO, Scopus). Initial searches were run in Oct 2018 and search updates were run in May 2023. Searches were also run in Google Scholar. To ensure comprehensive coverage, a health sciences librarian (blinded) designed the PubMed search strategy and then adapted that search strategy for use in other databases. The search strings utilized a combination of natural language and, where applicable, controlled vocabulary to cover the concepts of “technology” and “family or domestic violence.” In instances where possible, the search results were limited to articles published in the English language. The full list of search strings from different databases is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Search engine | Search string |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (("Mobile Applications"[Mesh] OR "Internet"[Mesh] OR "Cell Phone"[Mesh] OR "Videoconferencing"[Mesh] OR "Crowdsourcing"[Mesh] OR smartphone[tiab] OR app[tiab]) AND ("Intimate Partner Violence"[Mesh] OR "Gender-Based Violence"[Mesh] OR "Domestic Violence"[Mesh] OR intimate partner violence[tiab] OR domestic violence[tiab] OR child abuse[tiab] OR spouse abuse[tiab] OR elder abuse [tiab])) |

| PsycINFO | ((online social networks/OR social media/OR online community/OR mobile application*.ti,ab. OR exp mobile devices/OR text messaging/OR computer applications/OR exp electronic communication/OR (smartphone* or app).ti,ab.) AND (domestic violence/or child abuse/or elder abuse/or emotional abuse/or intimate partner violence/or marital conflict/or partner abuse/OR (domestic abuse or domestic violence or intimate partner violence or child abuse or spouse abuse or elder abuse).ti,ab.)) NOT (0200.pt. OR 0240.pt. OR 0280.pt. OR 0400.pt.) |

| CINAHL | ((TI mobile application* OR AB mobile application* OR TI app OR AB app OR TI smartphone* OR AB smartphone* OR TI facebook OR AB facebook OR TI Twitter OR AB Twitter OR TI social media OR AB social media OR TI social network* OR AB social network* OR MH "Mobile Applications" OR MH "Cellular Phone" OR MH "Text Messaging" OR MH "Smartphone+" OR MH "Crowdsourcing" OR MH "Online Services") AND (TI domestic violence OR AB domestic violence OR TI domestic abuse OR AB domestic abuse OR TI intimate partner violence OR AB intimate partner violence OR TI spouse abuse OR AB spouse abuse OR TI child abuse OR AB child abuse OR AB elder abuse OR MH "Domestic Violence+")) NOT PT dissertation |

| Scopus | ("domestic violence" OR "domestic abuse" OR "intimate partner violence" OR "spouse abuse" OR "child abuse" OR "partner abuse" OR "gender based violence" OR “elder abuse”) ("mobile application*" OR app OR smartphone* OR "cell*phone*" OR "text messag*" OR "smartphone*" OR "crowdsourcing") |

| Google Scholar | "Mobile Applications" OR "Internet"OR "Cell Phone" OR "Videoconferencing" OR "Crowdsourcing" OR ''smartphone'' OR ''app'' AND "Intimate Partner Violence" OR "Gender-Based Violence" OR “Elder abuse” |

Search string from different search engines (Worldwide publications, from date of inception to May 2023).

Definition of DV

In this article, abuse that could happen in a household setting in the United States, including child abuse, IPV and elder abuse, regardless of the relationship between survivors and perpetrators will be considered as DV. Specifically, DV can occur between a parent and child, or siblings, while IPV can only occur between romantic partners who may or may not be living together in the same household.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria include 1) health information technology interventions applied 2) women with DV experiences (including IPV, child abuse and elder abuse) 3) published between January 2008 and May 2023. Studies related to dating violence and social media were excluded because the settings could be out of the household in the United States. Editorials, commentaries, non-peer reviewed articles, study protocols, conference abstracts, and non-English articles were also excluded.

Review Process

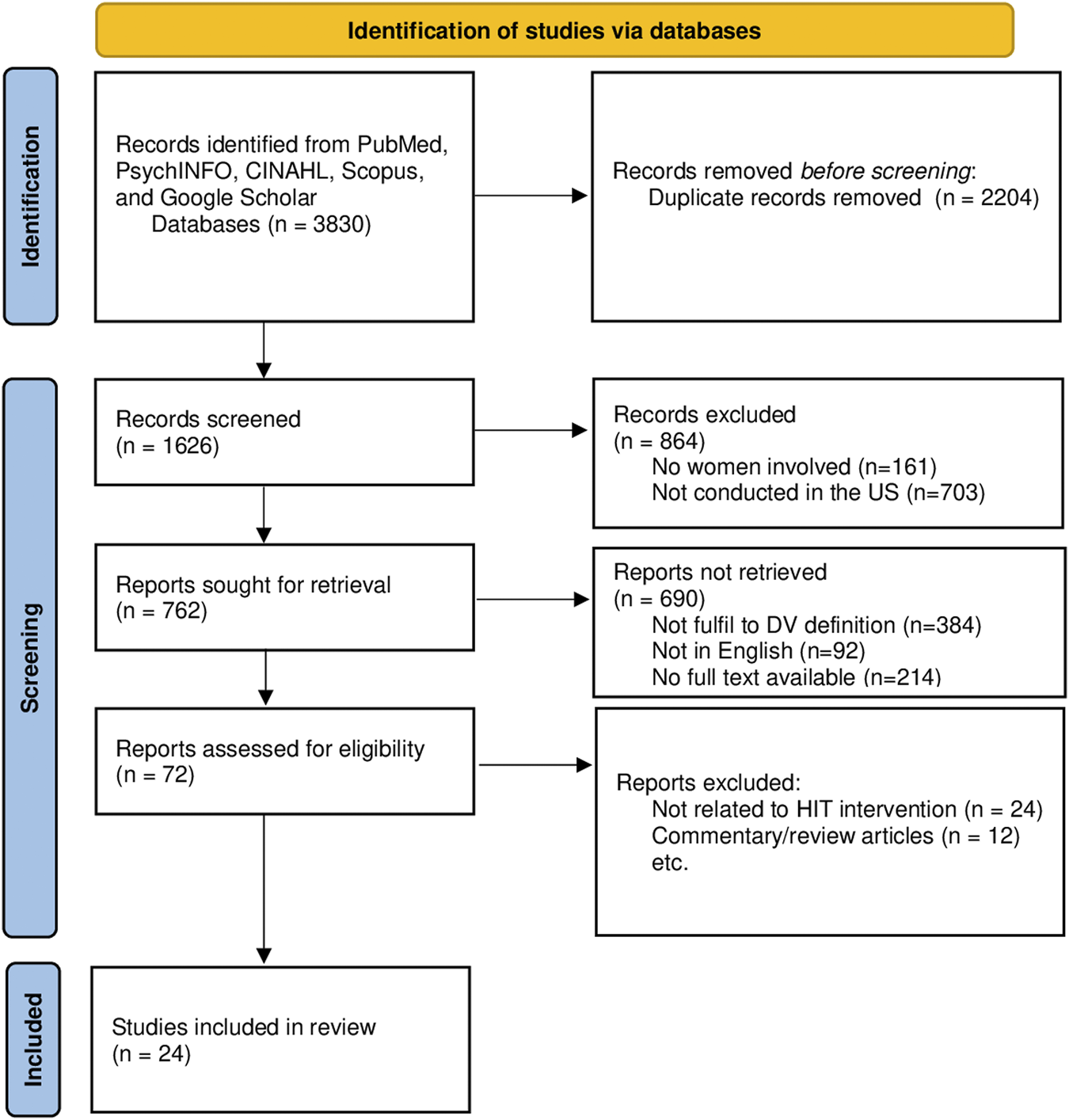

In the initial phase (Figure 1), articles were assessed based on their titles and abstracts, specifically examining their relevance to technology interventions for DV. Articles did not include women, or not conducted in the United States were not retrieved. Subsequently, in the second stage, full-text documents were obtained and subjected to qualitative review, guided by inclusion criteria. Prior to screening, a training session was conducted where reviewers evaluated a set of sample records together. A 75% inter-rater agreement was achieved among reviewers on this initial set before proceeding to the formal screening. During the formal screening, two independent reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of the records and categorized them as “included,” “excluded” or “uncertain” based on the relevancy to HIT interventions for DV. The reasons for exclusions include not related to HIT intervention, review articles, or any commentary articles. For any uncertain records, a senior researcher (BLINDED) resolved the status of the record.

FIGURE 1

Preferred reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Worldwide publications, from date of inception to May 2023).

Data Abstraction

Two reviewers independently charted data from each eligible articles. Any disagreements were resolved through group discussions or adjudication by a third author. The variables in the spreadsheet were organized into three categories: 1) classification of the intervention (including study purpose, technology, type of intervention, and abuse), 2) descriptive details (such as sample size, location, and settings), and 3) intervention outcomes (including physical safety, psychological, and technological outcomes). This scoping review followed the guidelines from Arksey and O’Malley [24].

Results

A total of 3,830 articles were identified from four academic databases, as well as from Google Scholar. 2,204 duplicates and irrelevant articles were removed, and 72 articles underwent a more detailed screening based on the abstract and titles. 48 articles were subsequently removed due to irrelevance to the research questions or ineligibility to the predefined criteria (e.g., non-intervention studies, exploratory studies conducted in non-U.S. territory). Finally, twenty-four articles (N = 24) met all of the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Figure 1). Table 2 listed the participant characteristics, purpose of study, purpose of intervention and types of technology, while Table 3 described the outcomes of interventions measured across studies.

TABLE 2

| No. | Authors (Year) | Purposes of the study | Types of technology | Purpose of intervention | Participants characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Location | Races | Age (mean) | |||||

| 1 | Bacchus, et al (2016) | Explore perinatal home visitor’s and women’s perceptions and experiences of the Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE) using mHealth technology or paper-based method. | Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE) mHealth Technology | Exploration | N = 26 | Metropolitan area | White, Black, Mixed |

20–27 mainly |

| 2 | Bloom, et al (2014) | Evaluate the feasibility of Internet-based safety planning for rural and urban abused pregnant women and practicality of recruitment procedures for future trials. | Online safety planning intervention | Prevention | N = 46 | N/A | White | 25 |

| 3 | Blumling, et al (2018) | Evaluate a standardized patient simulation experience depicting a victim of IPV on undergraduate nursing student knowledge and confidence in assessment and intervention of IPV | Standardized patient simulation | Education | N = 57 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | Choo, et al (2016) | Examine the feasibility and acceptability of a computer-based program and telephone booster for drug-using women reporting IPV. | Web-based BSAFER intervention and booster phone calls | Education | N = 40 | Metropolitan area | Non-white, Hispanic/Latino | 25 |

| 5 | Constantino, et al (2015) | Compare the effectiveness of online, face-to-face and waitlist control intervention of the HELPP based on personal, interpersonal and community level | Online, face-to-face, Wait-list control HELPP intervention “Email” |

Education | N = 32 | Metropolitan area | White, Black, Asian | 40 |

| 6 | Eden, et al (2015) | To test the effectiveness of a safety decision aid compared with usual safety planning (control) delivered through a secure website, using a multistate RCT design. | Internet safety decision aid | Prevention | N = 708 | Metropolitan area | White Black Asian Native American Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Other Multi-racial |

33 |

| 7 | Ejaz, et al (2017) | Comparing the managers’ knowledge change after receiving educational online training modules about the background of abuse, screening and reporting abuse. | Online training modules | Education | N = 453 | Metropolitan area | N/A | N/A |

| 8 | Glass, et al (2017) | To compare safety and mental health outcomes at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months among abused women randomized to (1) a tailored, internet-based safety decision aid or (2) control website. | Internet safety decision aid | Prevention | N = 672 | Metropolitan area | White Black Asian Native American Hawaiian or Pacific Islander Other Multi-racial |

33 |

| 9 | Goldman, et al (2019) | Examine the knowledge level and feasibility of using a smartphone application to identify victims of sexual exploitation. | SART START smartphone application | Assessment | N = 103 | N/A | White Asian Black Other |

31–40 mainly |

| 10 | Gur, et al (2016) | Explore the use of GPS for domestic violence or Intimate Partner Violence in pretrial programs | GPS | Exploration | N = 114 | Metropolitan and rural areas | White | 70% were 40 or older |

| 11. | Harris, et al (2009) | Evaluate the costs and effectiveness of promoting online CME about IPV training to physicians. | Free CME online program | Education | N = 1869 | Metropolitan area | N/A | N/A |

| 12 | Hassija, et al (2010) | To evaluate the effectiveness and feasibility of videoconferencing technology to provide evidence-based treatment to rural domestic violence and sexual assault populations | Videoconferencing | Prevention | N = 13 | Metropolitan and rural areas | White | 30 |

| 13 | Ibarra, et al (2014) | To examine “styles of surveillance” among community corrections officers using Electronic monitoring, by employing a specific and comparative analysis from GPS in DV in the context of pretrial supervision | GPS | Exploration | N = 50 | Metropolitan and rural areas | N/A | N/A |

| 14 | Jabaley, et al (2011) | Examine the iPhone™ when used as an assessment tool and an enhancement to an evidence-based, in-home child safety intervention. | iPhone™ | Assessment | N = 3 families | Metropolitan area | N/A | N/A |

| 15 | Lefever, et al (2008) | Assess the feasibility of using cell phone interviews to learn more about the quality of daily parenting and child neglect. | Cell phone interview | Screening | Study 1:N = 45 Study 2: N = 544 |

Metropolitan area | African European Hispanic, other ethnic |

Adolescent mother: 17.5 Adult mother: 26.5 |

| 16 | MacLeod, et al (2009) | To assess whether the telemedicine would increase the ability of the rural provider to perform a complete and accurate sexual assault examination. | Telemedicine video-conferencing | Assessment | N = 42 | Rural area | N/A | 7 |

| 17 | McAndrew, et al (2014) | To determine whether the dentistry’s online tutorial on domestic violence is effective for dental students poised to embark on their professional careers | Online tutorial | Education Prevention Detection |

N = 25 | Metropolitan area | N/A | N/A |

| 18 | Paranal, et al (2012) | To discuss the benefits and limitations of conducting online organizational trainings from the perspective of participants, including what participants found effective, what challenges were most commonly encountered, and trainee perspectives of the program’s overall impact | Online training | Education | N = 218 | Metropolitan area | N/A | N/A |

| 19 | Rothman, et al (2009) | To assess the proportion of battered women’s shelter residents who use e-mail in communication | Assessment | N = 57 | Metropolitan area | White Black Hispanic Asian, others |

30 | |

| 20 | Sargent, et al (2016) | To assess the effects of an online program (Change A Life) designed to educate individuals about children’s exposure to domestic violence, and to increase individuals’ self-efficacy for providing support to children exposed to DV. | Online program | Education Prevention |

N = 255 | Metropolitan and rural area | White, Black, Hispanic Asian |

39 |

| 21 | Thraen, et al (2008) | Evaluate the usability and satisfaction differences on a Web-based application developed for the remote sharing of child maltreatment assessment. | Web-based application TeleCAM |

Assessment | N = 11 | Metropolitan area | White African American |

N/A |

| 22 | Abujarad, et al 2021 |

Developed and evaluated the usability of a self-administered digital health tool, VOICES, that can be used to screen, educate, and motivate older adults to self-report elder abuse. | A tablet-based self-administrated digital health tool | Education Assessment Self-identification Interview |

N = 38 | Metropolitan area | African, American Asian White Other |

61–98 |

| 23 | Agu, et al 2020 |

Improve intimate partner violence service delivery. | Two days of interactive sessions, six webinars, testing strategies using the improvement model (Plan-Do-Study-Act) and three online surveys | Education Assessment |

N = 98 (IPV home visitors) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 24 | Bagwell-Gray, et al 2021 |

Adapt and test the myPlan web app intervention for Native American women. | Smartphone application | Exploration | N = 83 | Metropolitan and rural areas | N/A | N/A |

Literature summary of critical findings among 24 studies from 2008 to 2023 (Worldwide publications, from date of inception to May 2023).

TABLE 3

| No. | Authors (Year) | Types of abuse | Study design | Intervention outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical safety outcomes | Psychological outcomes | Technology outcomes | ||||

| 1 | Bacchus, et al (2016) | IPV | Qualitative Interviews | N/A | N/A | “The computer tablet viewed as a safe and confidential way for DV women to disclose their experiences; tablet helped to establish trust and rapport between victim and providers; The technology helped reduce the anticipated stigma associated with disclosing abuse.” “Both methods of screening were positively influenced by factors like having established trust and rapport, and good interpersonal communication.” |

| 2 | Bloom, et al (2014) | IPV | Feasibility | Danger assessment score indicated severe danger in the abusive relationship. (M = 16.1) | N/A | The average time to completion was 10.3 days (SD = 16.3 days, range = 0–68 days), with rural women taking an average of 2.2 days longer than urban women (11.6 vs. 9.4 days, respectively). A higher percentage of rural women (63.2%) reported using a home computer compared with their urban counterparts (48.4%). A lower percentage of rural women used a computer at a friend’s or family member’s house (25.3% vs. 34.3, respectively) 20% of e-mail contacts from potential participants originated from a mobile device. 19.5% of the women completed the baseline session from a mobile device. |

| 3 | Blumling, et al (2018) | IPV | Cross-sectional study | N/A | N/A | The simulation technology demonstrated significant increase in confidence (p < 0.001), and knowledge (p < 0.001). |

| 4 | Choo, et al (2016) | IPV | RCT | Past month drug use, the occurrence of psychological, physical, and sexual violence. | N/A | The web-based intervention plus telephone is highly feasible in the emergency care setting; High acceptability, satisfaction, and usability in the web-based intervention evaluation Mean System Usability Scale (SUS) for the BSAFER Web program was 84 (95% CI 78–89) of 100; mean Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) was 28 (95% CI 26–29) of 32. |

| 5 | Constantino, et al (2015) | IPV | Sequential, transformative mixed-methods design | N/A | Significant improvement in anxiety (p = 0.01), depression (p < 0.001) and social support (p < 0.001) in the pre-test score and post-test score for each of the groups; Online intervention may lessen social risks and inhibitions, enhances sharing of unwelcome thoughts and painful feelings. | |

| 6 | Eden, et al (2015) | IPV | RCT | Intervention-group women had a greater reduction in total decisional conflict, uncertainty and feeling unsupported than control participants (p < 0.05). | N/A | N/A |

| 7 | Ejaz, et al (2017) | Elder abuse | Feasibility study | N/A | N/A | Significant improvement in knowledge for abuse background and report system (67%); The module “Screening of abuse” is the weakest module as it lacks illustrations relating to various types of self-neglect (environmental, health-related, and behavioral) |

| 8 | Glass, et al (2017) | IPV | RCT community-based | Women who left the abuser had higher baseline risk (p =0.003); they found the safety behaviors more helpful (p = 0.037) and experienced less decisional conflict (p = 0.042). | Women in intervention group had greater reductions in psychological IPV (p = 0.001) and sexual IPV (p = 0.001). | N/A |

| 9 | Goldman, et al (2019) | Child abuse | Feasibility | N/A | N/A | Knowledge increased significantly in smartphone application intervention group; the application reported as easy to use (59%), useful (63.9%) and preferred to obtain information than traditional printed materials (85%). |

| 10 | Gur, et al (2016) | IPV DV |

Feasibility | N/A | N/A | The GPS in DV is important in providing enhanced supervision (96%), keeping victim safer (94%), allowing defendants to live in the community while awaiting trial (86%), receiving satisfaction monitoring information and supervising their clients easier for officers (51%); GPS technology facilitated asking’ hard questions and help guiding client’s decision making (92%). |

| 11. | Harris, et al (2009) | IPV | N/A | N/A | N/A | The overall quality of the online CME program was rated highly in knowledge improvement (M = 4.52/5); Direct email was the most effective, cost efficient, and common strategy of online intervention recruitment. |

| 12 | Hassija, et al (2010) | DV | N/A | N/A | Participants exhibited large reductions on PTSD severity checklist (M = 32.20, SD = 12.68, d = 1.17). And depressive symptoms (M = 13.07, SD = 9.07, d = 1.24); Clients’ reports of satisfaction with the provision of psychological services via videoconferencing (M = 52.93, SD = 2.43). | Videoconferencing is effective in providing specialized, evidence-based psychological services to rural domestic violence and sexual assault populations. |

| 13 | Ibarra, et al (2014) | DV | Qualitative interview/comparative analysis | N/A | N/A | The GPS is useful in tracking location, building trustful relationship, facilitating the interviews, and being a source of solace against the threat of false accusation. |

| 14 | Jabaley, et al (2011) | Child abuse | N/A | Observation System: The Home Accident Prevention Inventory-Revised (HAPI-R) demonstrated significant decrease in hazards among families (Range: 74%–97%); Parents considered their homes safer and expressed confidence in recognizing and securing hazards. |

N/A | Communication via iPhone on logistical questions or reminders demonstrated good results; 86% Reported with favorable reactions to the iPhone texting communication. |

| 15 | Lefever, et al (2008) | Child Abuse | Longitudinal study | Higher parenting essentials associated with higher knowledge of child development, higher scores on the parenting styles measure, lower child abuse potential, and lower scores on the history of neglect measure. | N/A | Cell phone offers greater level of mobility and convenience at a lower cost than landline phones; reported as useful in intervening with mothers at risk of suboptimal parenting and child neglect. |

| 16 | MacLeod, et al (2009) | Child abuse | N/A | N/A | Rankings of practitioners’ skills and the telemedicine consultation effectiveness were high, with 82% of cases. | Telemedicine consultations showed good scores in the use of the multimethod examination technique and the use of adjunct techniques. The mean duration of the consultations was 71 min (range: 25–210 min). The consultations resulted in changes in interview methods (47%), the use of the multimethod examination technique (86%), and the use of adjunct techniques (40%). There were 9 acute sexual assault telemedicine consults that resulted in changes to the collection of forensic evidence (89%). Rankings of practitioners’ skills and the telemedicine consult effectiveness were high, with 82% of cases scoring ≥5 on a 7-point Likert scale. |

| 17 | McAndrew, et al (2014) | IPV | Quasi-experimental | N/A | N/A | “The online tutorial was effective in increasing the participants’ perceived preparation, knowledge, and self-efficacy and decreasing perceptions of provider constraints in managing victims of IPV.” |

| 18 | Paranal, et al (2012) | Child abuse | Non-equivalent group design | N/A | N/A | Individual participants rated the training content (9.13) and found the training format interesting (8.88), useful (8.9) and ease of use above neutral (6.4). 80% of the participants viewed all the video clips. Organization perceived online training as easy to administer to staff (Mean:7.6), prefer online training (Mean:7.25); Effective in teaching adults about child abuse (Mean:8.97). |

| 19 | Rothman, et al (2009) | IPV | N/A | N/A | N/A | Most shelter residents have email accounts (80%), prefer using email as communication and keep in touch with the advocates; 88% reported as a safe method. |

| 20 | Sargent, et al (2016) | DV | RCT | N/A | Knowledge about DV consequences, self-efficacy, and how to help children exposed to DV reported as significant improvement in intervention group. | Online program is effective to reach large numbers of people inexpensively and quickly raise public awareness of DV effectively, offer a cost-effective way and allow participants to move through the program at their own pace. |

| 21 | Thraen, et al (2008) | Child abuse | Mixed methods | N/A | N/A | 85% Participants used desktop PCs on a regular basis; reported the easiness to save and upload images from Web browser (81%); able to download and install plug-ins (72%); E-mail used for assessing child maltreatment (55%). |

| 22 | Abujarad, et al 2021 |

Elder abuse | Mixed methods | N/A | N/A | Overall scored the VOICES usability score of 86.6, while 93% participants indicated the willingness to recommend digital VOICES tool to others and 100% indicated full understanding of health information and content. |

| 23 | Agu, et al 2020 |

IPV | Mixed methods | N/A | N/A | From baseline to final survey, participants reported accurate knowledge (change: 2.3%–34.8%), confidence (change: 31.8%–37.9%), system awareness (change: 22.7%–53.5%), and increased IPV screening rate (change: 88.0%–91.0%) and referrals (change: 43.0%–100.0%). |

| 24 | Bagwell-Gray, et al 2021 |

IPV | Qualitative interview | N/A | N/A | By understanding IPV’s culture specific risks and protective factors, the web-based safety app called myPlan (renamed ourCircle) can better provide IPV Native American women with culturally specific safety priorities and security strategies. |

Literature summary of critical findings among 24 studies from 2008 to 2023 (Worldwide publications, from date of inception to May 2023).

Note: DV, domestic violence; IPV, intimate partner violence; M, mean; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Types of Technology

Seven web-based interventions were identified; five of them collected data from a stand-alone website [25–29]. Four online trainings were designed for multidisciplinary healthcare professionals [30–33]. Five studies leveraged mobile devices to provide intervention [34–38]. Two studies used email as an intervention tool [31, 39]. Another two studies used Global Positioning System (GPS) as interventions [40, 41]. One article used videoconferencing as intervention [42], and another study utilized simulation technology to tackle domestic violence [30].

Types of Intervention

Four studies focused on prevention [25–27, 42], and ten focused on education [28, 30–33, 37, 39, 43–45]. Five studies delineated the effectiveness of HIT intervention [34, 40, 41, 46, 47] and three focused on various types of DV assessment [29, 35, 48]. Only one study emphasized screening for patients [36].

Participant Characteristics

Different types of DV survivors or potential survivors were captured in this review, such as adolescent mothers [36], abused women [27, 42], pregnant women [25, 46], and battered women [47]. Simultaneously, participants were extended to various professions like nurses [30], physicians [31], dental students [32], and law enforcement officers [34]. Among twenty-four studies, the sample sizes were ranged from 11 to 1,869. The sample characteristics and demographics were diversified. The majority of studies recruited participants from designated clinical settings (e.g., hospitals, clinics), community centers (e.g., non-governmental organizations, shelters), schools, and criminal justice services departments. A mean age of 7–40 was found across studies.

The review studies include people of diverse ethnic backgrounds, including Whites, African Americans, Hispanic Latinos, Asians, and others; however, the samples were predominantly White (N = 13). Only one article was conducted in rural areas [48] compared to fourteen articles in metropolitan areas [26, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35–37, 39, 43–47]. Another five articles have been discussed domestic violence in both metropolitan and rural areas [28, 38, 40–42].

Types of Abuse

Four types of abuse were included. Twelve studies focused on intimate partner violence (IPV) [25–27, 30–33, 38, 39, 43, 46, 47], six highlighted child abuse [29, 34–36, 45, 48], four illustrated DV [28, 40–42], and two studies targeted on elder abuse [37, 44].

Study Designs

Various research methods are used, including randomized controlled trials (N = 5) [26–28, 43, 46], and longitudinal (N = 1) [36], mixed methods (N = 5) [29, 33, 37–39], feasibility tests (N = 5) [25, 30, 34, 40, 44], non-equivalent group design (N = 1) [45], quasi-experimental design (N = 1) [32], as well as qualitative studies (N = 1) [41].

Intervention Outcomes

Physical Safety Outcomes

Physical safety outcomes were reported in five studies [25–27, 36, 43]. Only one study assessed the abuse score for physical sexual violence [43], while the other one evaluated the neglect score among children at a home setting [36]. Both studies indicated a decrease in scores for both neglect and abuse. Moreover, three other studies showed improvement in danger assessment, safety strategies, and safety behaviors using different types of measurements [25–27].

Psychological Outcomes

Depression, anxiety, and PTSD were reported as psychological health outcomes in three articles [25, 39, 42]. Bloom et al. (2014), Constantino et al. (2015), and Hassija et al. (2010) showed improvement in depression [25, 39, 42], Constantino et al. (2015) and Bloom et al. (2014) also reported improvement in PTSD and anxiety outcomes in their studies [25, 39]. Choo et al. (2016) and Lefever et al. (2008) illustrated the abuse reduction as an outcome measure [36, 43]. Only one article reported improved social support [39].

Technological Outcomes

Technological interventions effectiveness was evaluated in eight studies, which demonstrated strong feasibility, usability, and acceptability [25, 29, 34, 36, 37, 42–44]. Bloom et al. (2004), Choo et al. (2016), Thraen et al. (2008), and Abujarad et al. (2021) measured the usability [25, 29, 37, 43], while Bloom et al. (2014), Choo et al. (2016), Ejaz et al. (2017), Goldman et al. (2019), Hassija et al. (2010), and Lefever et al. (2008) measured feasibility [25, 34, 36, 42–44], and Choo et al. (2016) measured the acceptability of the technological intervention [43].

Discussion

Our study synthesized research articles on the technology interventions, research designs, and reports on the overall state of DV technology over the past decade. The results demonstrated the diverse application of technological interventions among women with DV experiences. Seven types of technology interventions were identified for DV (e.g., mobile applications, online training, web-based intervention, Global Positioning System (GPS), emails, videoconferencing, and simulation), and the majority of studies assessed usability, acceptability, and participants’ satisfaction. Several studies assessed psychological wellbeing outcomes, including stress levels, quality of life, sleep quality, and emotional needs.

HIT Interventions Dominant in IPV

Our results highlight that HIT interventions focused on different types of abuse within families, with Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) being the most common and elder abuse being the least. Research has demonstrated that young and educated people were the population group more willing to accept and adopt HIT interventions in clinical and community settings, while older adults staying at home were unwilling to use these health interventions due to perceived barriers, such as inertia, cognitive impairment, and physical disabilities [49, 50]. However, this situation might decline because of aging and the rise of computer literacy among the elderly. According to Internet World Statistics, over 89 percent of the U.S. population were internet users in 2019 [51]. The web-literate population has been growing and constantly surging with the increasing reliance on technology, machine learning, and artificial intelligence in our daily lives. Fleming (2015) delineated that over 60% of people older than 50 used technologies to browse social networking sites, take photos, and communicate in text messages [52]. Although those older than 65 may have more perceived barriers to using health technology, such as hearing deficit and cognitive impairment, they will accept new technologies when the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. There has been a proliferation of research concerning the utilization of technology in addressing elder abuse, highlighting its significant feasibility, accessibility, and effectiveness in monitoring neglect or physiological changes among elder abuse survivors, both at home and in clinical settings [53]. Therefore, it is anticipated that computer literacy and the implementation of HIT interventions among the elderly will continue to grow, leading to the expansion of interventions targeting aging in the forthcoming decades.

HIT Interventions Thrives in Urban and Rural Areas

The findings of our study also revealed that the use of HIT had been employed to assist DV survivors residing in both urban and rural settings. Due to limited access to healthcare services, women residing in rural areas experiencing DV face difficulties in effectively addressing their DV situation [54]. Previously, individuals from rural areas who were DV survivors may not have benefitted from technological advancements and treatments due to the inadequate support available to them [54]. However, our review demonstrates that digital devices in rural areas hold promise for telemedicine, providing an interactive means of delivering care, making referrals, and offering diagnosis and screening for DV survivors who may be able to meet healthcare professionals physically in a clinic or hospital. As the digital literacy rate has consistently improved over the past decade, it is expected that the limitations of technical support (such as limited wireless devices, unstable Internet, and restricted access to technical assistance) are no longer hindrances to implementing HIT interventions in rural areas. The current body of research has explored the utilization of videoconferencing, interventions pertaining to medical appointments, counseling services, and danger assessments, all of which should be expanded to rural areas through digital platforms or means. It is anticipated that the utilization of teleconferencing and online counseling services will become even more prominent, as indicated by the expanding coverage of health insurance plans for online services and consultations that aimed at addressing the mental health needs of women with DV experiences.

Web-Based Interventions Provide Better Platform for Self-Disclosure

The utilization of web-based interventions has emerged as a growing trend in DV prevention and education. HIT offers several advantages, including convenience, interactive design, and the creation of an anonymous environment facilitated by the Internet. Given that DV survivors may be reluctant to engage in face-to-face social interactions due to fear of stigmatization, shame, guilt, and judgment [16], web-based interventions provide an anonymous platform that encourages survivors to disclose their traumatic experiences more vividly and seek help proactively. It is well-documented that the sense of anonymity and social distance feeling created by the online platform fosters candid, sensitive and traumatic conversations [55, 56]. It is noteworthy that effective patient-provider communication remains the linchpin of positive intervention outcomes, particularly when addressing sensitive topics such as DV. Technological advancements promise to promote truthful or effective communication between DV survivors and healthcare professionals.

While utilizing technology for DV was predominantly applied at the patient level, the application also extends to healthcare professionals’ training. Previous literature highlighted the lack of training provided for healthcare providers to screen DV cases, thereby weakening their ability to probe DV questions and the lack of empathic listening skills during consultations. As such, DV survivors easily suffer from delayed treatment or referral from physicians [57]. For future endeavors, DV training development can extend the targeted participants to more healthcare professionals who might be poorly equipped, such as new nursing staff, social workers, or counselors during the orientation program.

HIT Intervention Improved Physical Safety and Psychological Outcomes

HIT interventions have evaluated physical safety and psychological outcomes of women with DV experience. For instance, technology-based interventionshave heightened the awareness of safety strategies among women with DV experience, strengthening their sense of security and capacity to defend themselves from perpetrators within their households [27]. Mobile applications and online training programs have evaluated the current danger level for women, thereby increasing their prompt recognition and engagement in modifying their safety strategies [25]. By leveraging the use of technology, women can actively participate in reassessing their danger level and adapting their contingency plans [27]. They feel safer and find it easier to evaluate their situation on their smartphone [35]. Moreover, online platforms, emails, and messaging systems could reduce the risk of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among women experiencing DV [25, 39]. Technology provides a valuable platform for women to share and discuss their experiences with other survivors, aligning with previous research indicating that computer-based interventions can significantly improve social support, self-efficacy, and alleviate feelings of loneliness among rural women [58]. Consequently, HIT interventions can contribute to developing a stronger social support network for women facing DV.

There is a wealth of evidence showing the importance of emotional health towards women with DV experiences. However, our review indicated limited HIT intervention studies on assessing the emotional aspects of survivors’ experiences. For example, World Health Organization (WHO) demonstrated that women with IPV experience could have a higher demand for mental health services and an increased likelihood of psychological distress [59]. Women could experience emotional breakdown easier or the need to express themselves after traumatic experiences like DV. The anonymity and instant communication facilitated by mobile devices and the Internet, have provided opportunities for women to seek emotional support through texting through online platforms [60, 61]. This avenue enables better adaptations and enhances the quality of life following traumatic experiences caused by abusive relationships. Future HIT research endeavors could focus on improving the emotional status of survivors, thus promoting more favorable mental health outcomes.

Despite the positive outcomes reported in the literature, adopting HIT interventions for DV population is not without demerits. Several articles have delineated the limitations of using a technical device across community, clinical, and household settings [62, 63]. With reference to the power and control theory of DV, Baddam (2017) believes that the use of technology may exacerbate DV conditions as perpetrators can install tracker applications with GPS and blame the survivors for concealing the DV-related on their smartphones [64]. Perpetrators can turn out to be digital stalkers and constitute a significant threat to the victim, thereby permanently menacing psychological harm to the victim’s life [65].

HIT interventions have predominantly focused on raising awareness and building a digital platform for women to communicate. However, the evaluation of most interventions has typically been limited to pre-and post-test assessments, without consistently tracking long-term performance across multiple time points, such as 3, 6, and 9 months follow-up. Besides, existing research weights physical wellbeing higher than emotional wellbeing. There is currently no standardized measurement for assessing emotions via technology. It is suggested that incorporating advanced machine learning data analytics could be beneficial in extracting emotional needs and delivering emotional support through virtual messaging, such as natural language processing. Further research can capitalize on data analytics to develop an emotional terminology dictionary (e.g., terms related to resilience or distress) that provides a measurable benchmark for extracting and systematically quantifying emotional text data (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Implications | |

|---|---|

| For research | ➢ Evaluate at different time points ➢ Measure emotion condition ➢ Build ontology and leverage natural language processing to provide intervention ➢ Phase II and III trials (RCT) ➢ Multiple sites RCT |

| For practice | ➢ Web-based interventions in outpatient departments, pre-and-post natal visits, and home visits are more effective than other settings to reach potential women at risk for DV. ➢ Healthcare providers should be trained on DV screening like identifying women’s need in shelter, law protection, child care and family conflict solving. ➢ Technical support should be provided to organizations and clinicians |

| For policy | ➢ Translate the research into clinical and community settings. ➢ More funding is recommended to advance care via technology. ➢ Government should devise a policy to encourage a harmonious, respectful, and amicable environment in our families, workplaces, and communities. |

Literature summary on implications for practice, policy and research among 24 studies From 2008 to 2023 (Worldwide publications, from date of inception to May 2023).

Furthermore, it is important to direct future research avenues towards conducting phase II and III randomized controlled clinical trials to evaluate the preliminary effect size, side effects, and efficacy of the technology within a specific context. The majority of studies reviewed primarily focused on intervention design, feasibility, and prototype intervention. The subsequent step should involve an initial test of intervention in comparison with an appropriate alternative option. To identify outcomes and determine whether the measurement tools can detect the anticipated changes, a small sample size of 40–60 randomized controlled trials should be conducted, enabling the calculation of effect sizes for the intervention [66]. Future research can assess technological interventions by RCT in multiple settings or within a targeted setting to evaluate the efficacy.

This review also provides clinical insights into the context and environment of DV technology interventions. There are abundant web-based interventions, supported by theoretical and empirical evidence of their efficacy and feasibility, to raise awareness, enhance knowledge, and evaluate the specific needs of survivors. The utilization of web-based interventions in outpatient departments, prenatal or postnatal clinics, and home visits yield greater effectiveness compared to other settings. Moreover, existing literature highlights the importance of prioritizing victim’s needs during family conflict. Healthcare providers should be well-informed and trained in addressing the common application procedures and criteria for DV shelter, safety planning, law protection, and childcare through technology (i.e., online training, and case study from online).

The resolution of this public health concern necessitates the implementation of policy modifications or reforms. From a policy standpoint, it is crucial to facilitate the translation of research findings into practical applications in clinical and community settings. In accordance with the socioecological model, the prevention of DV should involve interventions targeting individuals, interpersonal relationships, societal structures, and community dynamics. The government and other relevant stakeholders should join forces and support to violence prevention research endeavors. Additionally, it is recommended to allocate increased funding towards research and innovative technologies to enhance the provision of nursing care and social services through technological interventions. Furthermore, the government should formulate policies to foster an atmosphere of harmony, respect, and amicability within families, workplaces, and communities.

Limitations

Studies included in this review have methodological considerations regarding the sample size, demographic characteristics, and design that should be noted with caution. Our included studies generally with small sample size, with several studies even being characterized as pilot or exploratory studies. Although the geographical settings from our studies include rural, suburban, urban, clinical, and community areas, the demographic characteristics still predominantly comprise a white population, which affected the overall generalizability of this study. Given the inconsistent reporting of study location among studies, we categorized them as either metropolitan or rural areas based on the current metrics from the U.S. Census Bureau (2016) [67]. Notably, only four studies took place in rural areas; future research should strive to clarify the definition or characteristics of locations where the interventions were conducted. Also, this review did not capture which forms of abuse were experienced by the DV survivors, which could influence the adherence to HIT intervention. We accept this trade-off for this scoping review as the adherence data was not provided in most of the studies. To maintain consistency and precise comparison in the analysis, this review specifically excluded dating violence, and articles using social media to collect data for DV. Therefore, it is possible that certain HIT interventions in DV populations were missed from this review.

Conclusion

By and large, DV remains a significant public health issue characterized by repetitive trauma within a vicious cycle, especially in the United States. This review highlights the current scope of HIT interventions in addressing DV. Our synthesized literature demonstrates substantial heterogeneity in intervention modalities, target populations, as well as study designs. HIT interventions offer an opportunity to reach potential survivors from underserved rural and suburban areas where access to healthcare services and DV support may be limited. Moreover, the range of HIT interventions for DV encompasses interventions at the patient and provider levels. Implementing online training modules for multidisciplinary healthcare practitioners shows promise in improving outcomes, as demonstrated by pre- and post-intervention assessments. While not all physical health outcomes were measured, the findings emphasize technology’s immense potential in reaching a broader and more heterogeneous sample base. Leveraging HIT can support DV survivors across individuals, families, and communities.

Statements

Author contributions

VH conceptualized the idea for the scoping review. BZ and BJ undertook the search strategy and ran the database searches. MK provided guidance on methodology. VH, BZ, and BJ screened abstracts and titles for inclusion/exclusion and full text articles for inclusion/exclusion. Data was extracted by VH, BZ, and BJ. VH, BZ, and BJ contributed to interpretation of results. Writing was completed by VH and BZ. KW and YL reviewed the manuscript and provided overall direction and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare(s) that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The main results of this study have been published as a PhD dissertation thesis and the approval to republish the data has been obtained.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Sugg N . Intimate Partner Violence: Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Intervention. Med Clin North Am (2015) 99:629–49. 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.012

2.

Department of Justice. Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) (2019). Available from: https://www.justice.gov/ovw (Accessed April 1, 2023).

3.

Black MC Basile KC Breiding MJ Smith SG Walters ML Merrick MT et al The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report (2011) (2011). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf (Accessed April 1, 2023).

4.

Peterson C Kearns MC McIntosh WL Estefan LF Nicolaidis C McCollister KE et al Lifetime Economic Burden of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. Am J Prev Med (2018) 55:433–44. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049

5.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infographic Based on Data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Nisvs): 2010-2012 State Report (2017). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS-infographic-2016.pdf (Accessed April 1, 2023).

6.

Dolezal TA McCollum DL Callahan MJ. Hidden Costs in Health Care: The Economic Impact of Violence and Abuse. MN: Academy on Violence and Abuse (2009).

7.

Carlson BE McNutt LA Choi DY . Childhood and Adult Abuse Among Women in Primary Health Care: Effects on Mental Health. J interpersonal violence (2003) 18:924–41. 10.1177/0886260503253882

8.

Golding JM . Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J Fam violence (1999) 14:99–132. 10.1023/a:1022079418229

9.

Hathaway JE Mucci LA Silverman JG Brooks DR Mathews R Pavlos CA . Health Status and Health Care Use of Massachusetts Women Reporting Partner Abuse. Am J Prev Med (2000) 19(4):302–7. 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00236-1

10.

Li Y Marshall CM Rees HC Nunez A Ezeanolue E Ehiri J . Intimate Partner Violence and HIV Infection Among Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Int AIDS Soc (2014) 17(1):18845. 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18845

11.

Breiding MJ Chen J Black MC. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States—2010. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21961 (Accessed April 1, 2023).

12.

Devries K Watts C Yoshihama M Kiss L Schraiber LB Deyessan N et al Violence Against Women Is Strongly Associated With Suicide Attempts: Evidence From the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women. Soc Sci Med (2011) 73(1):79–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006

13.

Desai S Arias I Thompson MP Basile KC . Childhood Victimization and Subsequent Adult Revictimization Assessed in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women and Men. Violence and victims (2002) 17(6):639–53. 10.1891/vivi.17.6.639.33725

14.

Choo E Ranney M Wetle T Morrow K Mello M Squires D et al Attitudes Toward Computer Interventions for Partner Abuse and Drug Use Among Women in the Emergency Department. Addict Disord their Treat (2015) 14:95–104. 10.1097/ADT.0000000000000057

15.

Suler J . The Online Disinhibition Effect. Cyberpsychol Behav (2004) 7:321–6. 10.1089/1094931041291295

16.

Tarzia L Iyer D Thrower E Hegarty K . “Technology Doesn’t Judge You”: Young Australian Women’s Views on Using the Internet and Smartphones to Address Intimate Partner Violence. J Technol Hum Serv (2017) 35:199–218. 10.1080/15228835.2017.1350616

17.

Thompson TG Brailer DJ . The Decade of Health Information Technology: Delivering Consumer-Centric and Information-Rich Health Car. Med Benefits (2004) 21:12.

18.

Ranney ML Choo EK Cunningham RM Spirito A Thorsen M Mello MJ et al Acceptability, Language, and Structure of Text Message-Based Behavioral Interventions for High-Risk Adolescent Females: A Qualitative Study. J Adolesc Health (2014) 55:33–40. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.017

19.

Gilroy H McFarlane J Nava A Maddoux J . Preferred Communication Methods of Abused Women. Public Health Nurs (2013) 30:402–8. 10.1111/phn.12030

20.

Al-Alosi H . Fighting Fire With Fire: Exploring the Potential of Technology to Help Victims Combat Intimate Partner Violence. Aggression Violent Behav (2020) 52:101376. 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101376

21.

Boydell KM Hodgins M Pignatiello A Teshima J Edwards H Willis D . Using Technology to Deliver Mental Health Services to Children and Youth: A Scoping Review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2014) 23(2):87–99. 10.1016/j.avb.2020.101376

22.

Tiwari A Recinos M Garner J Self-Brown S Momin R Durbha S et al Use of Technology in Evidence-Based Programs for Child Maltreatment and its Impact on Parent and Child Outcomes. Front digital Health (2023) 5:1224582. 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1224582

23.

Vandebosch H Botezat A Amodeo AL Pabian S Plichta P Puharić Z et al A Scoping Review of Technological Interventions to Address Ethnicity-Related Peer Aggression. Aggression violent Behav (2022) 67:101794. 10.1016/j.avb.2022.101794

24.

Arksey H O'Malley L . Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2005) 8(1):19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616

25.

Bloom TL Glass NE Case J Wright C Nolte K Parsons L . Feasibility of an Online Safety Planning Intervention for Rural and Urban Pregnant Abused Women. Nurs Res (2014) 63:243–51. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000036

26.

Eden KB Perrin NA Hanson GC Messing JT Bloom TL Campbell JC et al Use of Online Safety Decision Aid by Abused Women: Effect on Decisional Conflict in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Prev Med (2015) 48:372–83. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.027

27.

Glass NE Perrin NA Hanson GC Bloom TL Messing JT Clough AS et al The Longitudinal Impact of an Internet Safety Decision Aid for Abused Women. Am J Prev Med (2017) 52:606–15. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.014

28.

Sargent KS McDonald Rvu NL Jouriles EN . Evaluating an Online Program to Help Children Exposed to Domestic Violence: Results of Two Randomized Controlled Trials. J Fam Violence (2016) 31:647–54. 10.1007/s10896-016-9800-8

29.

Thraen IM Frasier L Cochella C Yaffe J Goede P . The Use of TeleCAM as a Remote Web-Based Application for Child Maltreatment Assessment, Peer Review, and Case Documentation. Child Maltreat (2008) 13(4):368–76. 10.1177/1077559508318068

30.

Blumling A Kameg K Cline T Szpak J Koller C . Evaluation of a Standardized Patient Simulation on Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Knowledge and Confidence Pertaining to Intimate Partner Violence. J forensic Nurs (2018) 14:174–9. 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000212

31.

Harris JJM Novalis‐Marine C Amend RW Surprenant ZJ . Promoting Free Online CME for Intimate Partner Violence: What Works at what Cost?J Contin Educ Health Professions (2009) 29:135–41. 10.1002/chp.20025

32.

McAndrew M Pierre GC Kojanis LC . Effectiveness of an Online Tutorial on Intimate Partner Violence for Dental Students: A Pilot Study. J Dent Educ (2014) 78:1176–81. 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2014.78.8.tb05789.x

33.

Agu N Michael-Asalu A Ramakrishnan R Birriel PC Balogun O Parish A et al Improving Intimate Partner Violence Services in home Visiting: A Multisite Learning Collaborative Approach. J Soc Serv Res (2019) 46:439–51. 10.1080/01488376.2019.1582452

34.

Goldman S Goyal D . Knowledge Regarding Child Victims of Commercial Sexual Exploitation and the Feasibility of Using a Smartphone Application: A Pilot Study. J forensic Nurs (2019) 15:103–9. 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000240

35.

Jabaley JJ Lutzker JR Whitaker DJ Self-Brown S . Using iPhones™ to Enhance and Reduce Face-To-Face home Safety Sessions Within SafeCare®: An Evidence-Based Child Maltreatment Prevention Program. J Fam Violence (2011) 26:377–85. 10.1007/s10896-011-9372-6

36.

Lefever JB Howard KS Lanzi RG Borkowski JG Atwater J Guest KC et al Cell Phones and the Measurement of Child Neglect: The Validity of the Parent-Child Activities Interview. Child Maltreat (2008) 13:320–33. 10.1177/1077559508320680

37.

Abujarad F Ulrich D Edwards C Choo E Pantalon MV Jubanyik K et al Development and Usability Evaluation of VOICES: A Digital Health Tool to Identify Elder Mistreatment. J Am Geriatr Soc (2021) 69:1469–78. 10.1111/jgs.17068

38.

Bagwell-Gray ME Loerzel E Dana Sacco G Messing J Glass N Sabri B et al From Myplan to Ourcircle: Adapting a Web-Based Safety Planning Intervention for Native American Women Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. J Ethnic Cult Divers Soc Work (2021) 30:163–80. 10.1080/15313204.2020.1770651

39.

Constantino RE Braxter B Ren D Burroughs JD Doswell WM Wu L et al Comparing Online With Face-To-Face HELPP Intervention in Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2015) 36:430–8. 10.3109/01612840.2014.991049

40.

Gur OM Ibarra PR Erez E . Specialization and the Use of GPS for Domestic Violence by Pretrial Programs: Findings From a National Survey of US Practitioners. J Technol Hum Serv (2016) 34:32–62. 10.1080/15228835.2016.1139418

41.

Ibarra PR Gur OM Erez E . Surveillance as Casework: Supervising Domestic Violence Defendants With GPS Technology. Crime, L Soc Change (2014) 62:417–44. 10.1007/s10611-014-9536-4

42.

Hassija C Gray MJ . The Effectiveness and Feasibility of Videoconferencing Technology to Provide Evidence-Based Treatment to Rural Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Populations. Telemed e-Health (2011) 17:309–15. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0147

43.

Choo EK Zlotnick C Strong DR Squires DD Tapé C Mello MJ . BSAFER: A Web-Based Intervention for Drug Use and Intimate Partner Violence Demonstrates Feasibility and Acceptability Among Women in the Emergency Department. Substance abuse (2016) 37:441–9. 10.1080/08897077.2015.1134755

44.

Ejaz FK Rose M Anetzberger G . Development and Implementation of Online Training Modules on Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation. J elder abuse neglect (2017) 29:73–101. 10.1080/08946566.2017.1307153

45.

Paranal RK Washington T Derrick C . Utilizing Online Training for Child Sexual Abuse Prevention: Benefits and Limitations. J Child Sex Abus (2012) 21:507–20. 10.1080/10538712.2012.697106

46.

Bacchus LJ Bullock L Sharps P Burnett C Schminkey DL Buller AM et al Infusing Technology Into Perinatal Home Visitation in the United States for Women Experiencing Intimate Partner Violence: Exploring the Interpretive Flexibility of an mHealth Intervention. J Med Internet Res (2016) 18:e302. 10.2196/jmir.6251

47.

Rothman EF Meade J Decker MR . E-Mail Use Among a Sample of Intimate Partner Violence Shelter Residents. Violence Against Women (2009) 15:736–44. 10.1177/1077801209332188

48.

MacLeod KJ Marcin JP Boyle C Miyamoto S Dimand RJ Rogers KK . Using Telemedicine to Improve the Care Delivered to Sexually Abused Children in Rural, Underserved Hospitals. Pediatrics (2009) 123:223–8. 10.1542/peds.2007-1921

49.

Jimison H Gorman P Woods S Nygren P Walker M Norris S et al Barriers and Drivers of Health Information Technology Use for the Elderly, Chronically Ill, and Underserved. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (2008) 175:1–1422.

50.

Lober WB Zierler B Herbaugh A Shinstrom SE Stolyar A Kim EH et al Barriers to the Use of a Personal Health Record by an Elderly Population. AMIA Annu Symp Proc (2006) 2006:514–8.

51.

Internet World Stats © Copyright. Miniwatts Marketing Group (2019). Available from: http://internetworldstats.com/ (Accessed April 8, 2019).

52.

Fleming G Reitsma R Pappafotopoulos T Duan X Birrel R. The State of Consumers and Technology Benchmark 2015. US. Cambridge, MA: Forrester (2015).

53.

Beach SR . The Role of Technology in Elder Abuse Research. In: DongX, editor. Elder Abuse: Research, Practice and Policy. Cham: Springer (2017). p. 201–14.

54.

Peek-Asa C Wallis A Harland K Beyer K Dickey P Saftlas A . Rural Disparity in Domestic Violence Prevalence and Access to Resources. J Womens Health (Larchmt) (2011) 20:1743–9. 10.1089/jwh.2011.2891

55.

Cantrell MA Lupinacci P . Methodological Issues in Online Data Collection. J Adv Nurs (2007) 60:544–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04448.x

56.

Wharton CM Hampl JS Hall R Winham DM . PCs or Paper-And Pencil:online Surveys for Data Collection. J Am Diet Assoc (2003) 103:1458–60. 10.1016/j.jada.2003.09.004

57.

Gillespie K Branjerdporn G Tighe K Carrasco A Baird K . Domestic Violence Screening in a Public Mental Health Service: A Qualitative Examination of Mental Health Clinician Responses to DFV. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs (2023) 30:472–80. 10.1111/jpm.12875

58.

Weinert C Cudney S Hill WG . Rural Women, Technology, and Self-Management of Chronic Illness. Can J Nurs Res (2008) 40:114–34.

59.

Ellsberg M Jansen HA Heise L Watts CH Garcia-Moreno C, WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Intimate Partner Violence and Women's Physical and Mental Health in the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence: An Observational Study. The lancet (2008) 371:1165–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X

60.

Kivran-Swaine F Brody S Diakopoulos N Naaman M . Of joy and Gender: Emotional Expression in Online Social Networks. In: PoltrockS, editor. Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work Companion. New York, NY, United States: Association for Computing Machinery (2012). p. 139–142.

61.

Hui V Constantino RE Lee YJ . Harnessing Machine Learning in Tackling Domestic Violence—An Integrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2023) 20(6):4984. 10.3390/ijerph20064984

62.

Murray CE Pow AM Chow A Nemati H White J . Domestic Violence Service Providers’ Needs and Perceptions of Technology: A Qualitative Study. J Technol Hum Serv (2015) 33:133–55. 10.1080/15228835.2014.1000558

63.

Southworth C Finn J Dawson S Fraser C Tucker S . Intimate Partner Violence, Technology, and Stalking. Violence Against Women (2007) 13:842–56. 10.1177/1077801207302045

64.

Baddam B . Technology and its Danger to Domestic Violence Victims: How Did He Find Me?Alb LJ Sci Tech (2017) 28:73.

65.

Melander LA . College Students' Perceptions of Intimate Partner Cyber Harassment. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw (2010) 13:263–8. 10.1089/cyber.2009.0221

66.

Gitlin LN . Introducing a New Intervention: An Overview of Research Phases and Common Challenges. Am J Occup Ther (2013) 67:177–84. 10.5014/ajot.2013.006742

67.

U.S. Census Bureau. Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey and Geography Brief (2016). Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/ua/Defining_Rural.pdf (Accessed April 1, 2023).

Summary

Keywords

health information technology, domestic violence, scoping review, women’s health, domestic abuse

Citation

Hui V, Zhang B, Jeon B, Wong KCA, Klem ML and Lee YJ (2024) Harnessing Health Information Technology in Domestic Violence in the United States: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev 45:1606654. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2024.1606654

Received

21 September 2023

Accepted

20 May 2024

Published

21 June 2024

Volume

45 - 2024

Edited by

Raquel Lucas, University Porto, Portugal

Reviewed by

Shirin Shahbazi Sighaldeh, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Sara Soares, University Porto, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Hui, Zhang, Jeon, Wong, Klem and Lee.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms. PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Vivian Hui, vivianc.hui@polyu.edu.hk

† Present address: Mary Lou Klem, Health Sciences Library System, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.