- 1Institute of Food and Beverage Innovation, Life Sciences and Facility Management, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Wädenswil, Switzerland

- 2Molecular Nutritional Science, Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Objectives: The objective of this scoping review was to summarize and provide a visual overview of the present-day knowledge on ecological determinants of eating behavior in community-dwelling elderly persons in relation with nutrition communication, considering the evolution of the field. The second objective was to integrate results in recommendations for the development of nutrition communication strategies.

Methods: A literature review was performed on Medline, PubMed and Google Scholar, according with the PRISMA protocol for scoping reviews. An a-priori analysis was executed by categorizing determinants from the literature according with the different levels represented in the ecological framework and an a-posteriori analysis by using VosViewer for a chronological bibliometric mapping analysis.

Results: Of 4029 articles retrieved, 77 were selected for analysis. Initial publications focused more on individual determinants of eating behavior. Over time, there was a shift towards a holistic view of eating behavior considering the “food environment”, including social networks, physical settings and public policy.

Conclusion: Beyond the individual, all ecological levels are relevant when targeting eating behavior in the elderly. Nutrition communication strategies should be structured considering these influences.

Introduction

According to the European Commission, by 2060 the percentage of individuals over 65 years will have risen from 19.3% (in 2016) to about 29.0% [1]. This shift is thought to have tremendous impacts on society [1, 2]. Although life expectancy has increased, time of “healthy life” is not increasing to a similar extent. Older adults face various health issues that may be improved if “structural, economic and social drivers” of health are addressed [3]. To date, measures taken to tackle these often fail. A better understanding of the health challenges associated with aging may improve the odds for good health and life quality in the elderly [1].

One of the major determinants of healthy aging is nutrition [4, 5]. Epidemiological studies suggest that maintaining a healthy diet leads to a decrease in morbidity specially related to cognitive decline and metabolic diseases, which also translates to reduced healthcare costs [6, 7]. These findings reinforce the importance of creating adequate nutrition interventions that lead the elderly to adjust their food choices so that their cognitive and overall health is maintained, or even improves [8].

One of the main challenges for healthcare providers, scientists and policy makers is to develop communication strategies to successfully convey scientific information to older adults resulting in sustainable behavioral changes [9]. To create successful evidence-based nutrition communication strategies, it is important understand how various internal and external determinants influence older adults’ food choice [10]. Findings of several studies suggest that eating behavior results from a complex interaction of factors not only directly related to the individual but also the contextual environment [11].

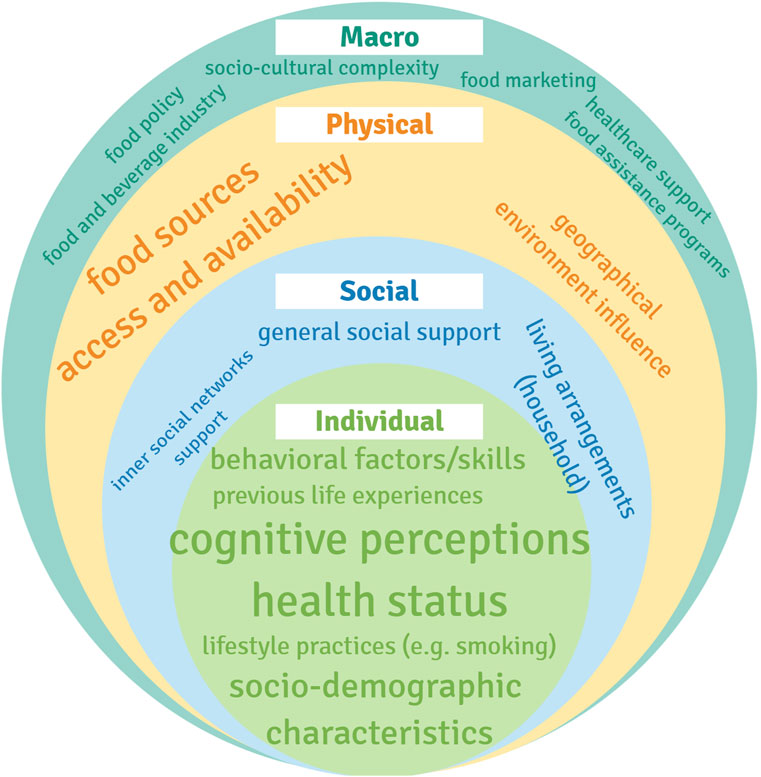

The contextual environment and its interaction with the individual are well portrayed in the “Ecological Framework”, a conceptual model composed of “spheres” that have an influence on human behaviors [12]. These spheres include individual, social, physical and macro level environments [12]. Furthermore, ecological determinants, and their interactions, that influence eating behavior in older adults need to be considered, while acknowledging that these are not static but may vary over time [13, 14]. Generally, this model is thought to be adequate for achieving a holistic understanding of eating behavior, thereby also laying the basis to the development of promising communication strategies focused on healthy eating [15].

Several studies investigated determinants of eating behavior in the elderly [4, 16–19]; however, study designs are heterogeneous both in methodology and determinants explored. There is a lack of an overview of the research performed. Undertaking a scoping review to provide a “map” of the body of literature in this field of research will be valuable to identify key findings and gaps for further investigation.

The objective of this scoping review with bibliometric mapping was to summarize and provide a visual overview about what is known regarding ecological determinants of eating behavior and food choice in older adults in relation with nutrition communication possibilities. The evolution of the field over time was considered as well. The second aim was to provide the basis for the development of novel, improved nutrition communication strategies targeting eating behavior in older adults.

There was a focus on literature after 2000 because the aging of the world population is a major trend of this period. Besides, during this century there was a huge advance in the use of digital technologies, which also affected food environments [20].

There is a need for an overview of what determines eating behavior in the elderly and how these determinants can be modulated towards healthier eating habits [21]. While the topic has been reviewed in some publications, the evolution of the field over time has not been studied so far. Besides, the subject has not been explored by using bibliometric mapping and the Ecological Framework [16, 21, 22].

Methods

Literature Search

This scoping review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Checklist and the framework for scoping reviews proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [23, 24]. Even though an internal review protocol was elaborated this was not registered in any open platform. The main research question was: What is known, from literature published from 2000 onwards, about ecological determinants of eating behavior in older adults that are important to consider for developing nutrition communication strategies?

The databases used for the search were Google Scholar, Medline (via ProQuest) and PubMed. The search expression used was: (elderly OR senior OR older OR age) AND (nutrition OR food OR eating OR meals OR feeding OR “eating behavior”) AND (communication OR education OR “health promotion” OR program) AND (determinants OR factors OR influence) NOT (child OR teenager OR adolescent OR student OR young). These terms were searched exclusively in the title of publications in Google Scholar, in the title and abstract in PubMed and anywhere except the full text in Medline. The ideal approach was to search in all databases “anywhere except full text”, however this was not possible. When possible, filters were applied so that only studies pertaining to humans, older than 65 years old were obtained. The age filter was added to reduce the number of hits obtained in the search to a feasible amount to analyze. The date of the last search was the 10th of June of 2021.

Firstly, duplicate articles were removed; afterwards the title and abstracts were examined, and articles selected according to the criteria for inclusion (Table 1) and exclusion (Table 2). The full text was read for the remaining articles to assess whether these fitted the criteria. If the full text was not available, the articles were excluded. Intervention studies were excluded because the goal was to obtain an overview of determinants of eating behavior in older adults’-built environment and not yet to explore how interventions targeted these. Selected publications were summarized according to the author(s), year of publication, origin, purpose, study characteristics, outcome measurements and results.

A-Priori and A-Posteriori Analyses

The a-priori analysis consisted of qualitatively extracting the ecological determinants of eating behavior mentioned in the literature by reading the publications. These determinants were grouped in categories and assigned to the levels of the Ecological Framework proposed by Story et al. [12]. Categories mentioned repeatedly in literature were given bigger font sizes than the ones mentioned less often.

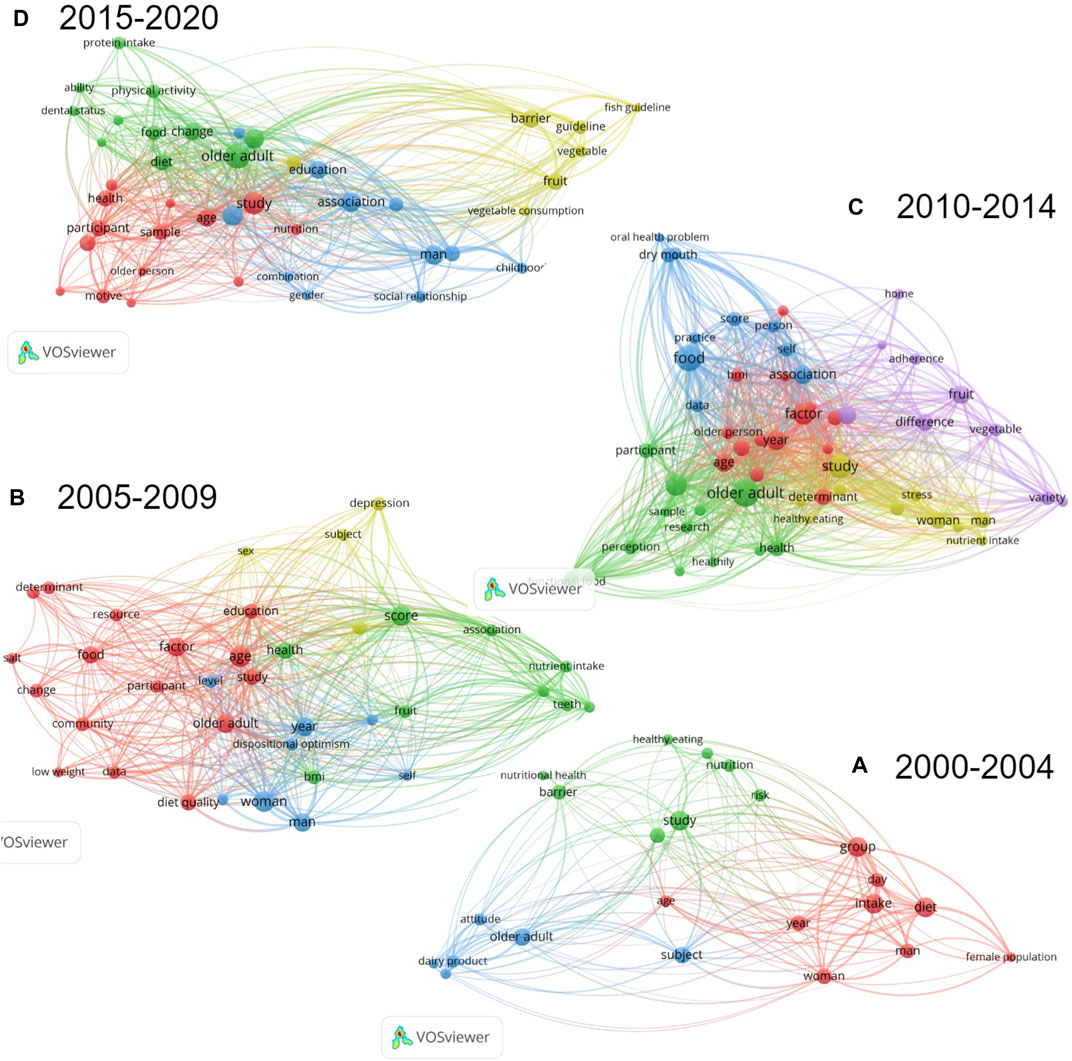

The software VosViewer was used for the a-posteriori analysis [25]. The software identified frequent terms among literature, these were considered to be the ones present in the title and abstract of the publications at least five times. As for the relevance score, no cut-off points were defined, the highest relevance scores obtained after the analysis were reported [25]. To analyze the evolution of research on this topic, publications were divided in four chronological periods: 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014 and 2015–2020.

Results

A total of 5,560 publications were identified in the search, which were reduced to 4,029 after removing duplicates. After screening the title and abstracts, there were 268 articles left. These were accessed for eligibility by reading the full text, 77 publications were selected for analysis (flow-chart in Figure 1). Despite of the use of the age filter, insightful studies with participants younger than 65 years were obtained. Hence an age range of 50 years or more was applied considering different definitions of older adult [21]. A summary of the publications selected can be found in Table 3. In Figure 2 is shown the Ecological Framework [12] with the categories of ecological determinants found in the literature and font sizes indicating more and less common categories. A more detailed overview of how determinants of eating behavior were grouped in categories can be found in the Supplementary Material (Ecological determinants of eating behavior in elderly grouped in categories, per period).

FIGURE 1. Flow-chart of the article selection process (scoping review, high-income countries, 2000–2020).

FIGURE 2. Ecological model adapted from the ecological framework proposed by Story et al. [12], with categories of determinants according with the literature analyzed (scoping review, high-income countries, 2000–2020).

When analyzing the 77 publications using VosViewer, relevance scores ranged between 0.04–3.17, 0.06–4.69, 0.08–3.38, 0.05–3.75 in the publications between 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014 and 2015–2020, respectively.

A total of 16 studies were published between 2000 and 2004. Among these, 23 terms co-occurred at least 5 times (Figure 3A). “Nutritional health” (3.17), “behavioral control” (2.45), “intention” (2.39) and “attitude” (1.93) were identified as frequent and relevant terms.

FIGURE 3. Cluster Visualization of Co-occurrence of Terms in Publications from (A) 2000–2004, (B) 2005–2009, (C) 2010–2014 and (D) 2015–2020, using Vosviewer [18] (scoping review, high-income countries, 2000–2020).

In the 14 articles published between 2005 and 2009, 37 terms co-occurred at least 5 times (Figure 3B) of which “functional dentition” (2.31) and “teeth” (1.92) were highly relevant. “Depression” (1.34) and “community” (0.79) also appeared frequently, however with a lower relevance score.

Among the 26 selected articles published between 2010 and 2014, a total of 58 terms co-occurred at least 5 times (Figure 3C). Herein, some of the most relevant terms were “information” (3.04), “oral health problem” (2.69) and “dry mouth” (2.08). “Food involvement” (0.84) also appeared although with a somewhat lower relevance score.

In the 21 studies published between 2015 and 2020, 43 terms occurred at least 5 times (Figure 3D) with “guideline” (2.81), “childhood” (2.20), “motive” (1.68), “dental status” (1.43) and “social relationship” (1.24) receiving quite high relevance scores.

The term “education” appeared first in the analysis of publications between 2005 and 2009; however, it had one of the lowest relevance scores and it kept appearing throughout all the periods with low relevance scores (0.11 or lower).

Some terms are not visible in Figure 3 as in case of lack of space the software automatically “hides” them.

Discussion

Research Between 2000–2004 Focused on Individual Determinants of Eating Behavior

When analyzing studies published between 2000 and 2004, it becomes apparent that publications focused mainly on individual determinants [26, 27]. Terms including “attitude”, “intention” and “behavioral control” were found to influence food choice among elderly individuals [27–30] (Figure 3A).

During this period, “nutritional health” was another term found in the bibliometric mapping. This was often explored as a result of individual characteristics as sex, (oral) health and ethnicity [28, 31–36]. Vitolins et al. [33] reported that African American men aged over 70 years consumed the lowest amounts of fruits and vegetables. Some studies published during this period also reported that education, marital status, social interaction and geographical differences were correlated with diet quality among older adults [26, 31, 37–41]. In a study from van Rossum et al. [38], lower educated individuals had a lower intake of fiber and a higher intake of saturated fat and cholesterol. “Resistance to change” was also referred to as an important determinant of food choice in elderly [27]. Studies further suggest that earlier life experiences may shape present food preferences. A study from Sindler et al. [29] investigating the effects in dietary habits of survivors of extreme life events like the Holocaust, found that this experience still shaped the eating behaviors at old age. Subjects reported having reserve foods at home and to avoid food waste [29]. Regarding geographical differences, Haveman-Nies et al. [37] reported that Southern European elderly had higher diet quality than Northern Europeans.

Research Between 2005–2009 Focused on the Effect of Social Determinants on Eating Behavior

In the following period (2005–2009), a more holistic view of determinants of eating behavior started to evolve, considering not only the individual but their built “food environment”, particularly community-related aspects. In this period, demographics as sex, ethnicity, education, income, living arrangements and geographic location continued to be reported as important determinants of quality of diet in elderly [16, 42–47]. However, these were often correlated with other collective determinants.

“Community” was a frequent term found in the publications between 2005 and 2009. It was reported that traditional foods typical of a community represent their identity and it is a complex task to replace these with healthier versions [48]. Payette and Shatenstein [16] reported that determinants of healthy eating were not only individual but also collective. Social interaction and support seem to positively influence older adults’ quality of diet, such as the intake of fruit and vegetables [16, 26]. The support of family, friends and healthcare professionals was mentioned as very important by elderly women at nutritional risk [49]. A study based in the Health Promotion model, reported that not only self-efficacy but also interpersonal support were associated with healthy eating in elderly people [50]. Underweight older adults stated that social contact during meals was crucial to maintaining healthy dietary patterns, loneliness was often associated with feelings of depression that led to lower appetite and the consumption of less balanced meals [51].

“Depression” was another term found among the literature. Payne et al. [52] compared the nutrient intake between a depressed group of elderly and a control group, the depressed group had higher intakes of alcohol and cholesterol when comparing with the control [52]. Furthermore, being positive about the aging process and perceiving fewer barriers to follow a healthy diet seemed to positively influence the consumption of healthy foods [53]. A study performed by Giltay et al. [53] reported that “dispositional optimist” in older men increased the likelihood of the consumption of healthy foods such as fruit, vegetables and whole-grain bread [53]. It has also been suggested that having food related goals as “cooking for others” were significant predictors of a varied diet [44].

“Teeth” and “functional dentition” were also frequent terms reported in the visual mapping from VosViewer. It has been shown that having a functional dentition significantly improves the consumption of fruits and vegetables in elderly males [54].

Research Between 2010–2014 Assessed Determinants of Food Choice as Life Experiences, Information and “Food Involvement”

Among publications between 2010 and 2014, “oral health problem” and “dry mouth” were oral health related terms that kept on appearing at the bibliometric mapping, these lead to problems as chewing difficulty and xerostomia [55–57]. It is likely that denture wearers and/or elderly with a low number of teeth either avoid foods that would create discomfort or use food modification techniques [55, 56, 58]. Quandt et al. [56] found a significant correlation between suffering from dry mouth and having a lower consumption of whole-grain foods. It has been proposed that taste and smell impairments that accompany the process of aging are related to sensory perception of food [59]. This in turn has been suggested to affect appetite [60, 61].

There were other recurring topics in the publications between 2010 and 2014. Attitudes and beliefs towards food were, once again, shown to influence eating behavior [62–64]. Individual motivations to eating healthy were described by Dijkstra et al. [65]. Elderly reported “Health”, “Feeling fit” and “Body weight” as the most important determinants of food choice [65]. Sex, socio-economic status, living arrangements, education, ethnicity and place of residence were also described as influencing eating behavior in elderly [59–61, 65–71]. It was reported that older adults with lower education level and income adhered less to vegetables and fish/fruit government guidelines respectively [71].

“Information” was another term that appeared between 2010 and 2014. In a study performed with elderly from several European countries it was reported that even though older adults are aware of information related to nutrition recommendations and open to follow them, they draw their own conclusions from these and try to make it fit their lifestyle, habits and culture [72]. Traditional and familiar foods, often resulting from family habits and other life-course experiences, have been shown to be the preferred by the majority of older adults [72]. Several studies reported that dietary patterns of older adults are bound to their cultural and ethnic background [61]. For instance, older adults living in Mediterranean countries typically have a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables when comparing with older adults from the United States [61]. Studies further suggest that open and curious elderly are more likely to adopt novel dietary habits [73]. Older adults report that advice and provision of information from healthcare professionals have the potential to highly influence their (functional) food consumption [74]. It seems that there is an opportunity for healthcare professionals to provide nutrition information to older adults with the potential to modulate their food choices, yet this needs to be tailored to the characteristics of each target group [74]. Furthermore, it is important to understand the process of interpretation of nutrition information of different sub-groups of elderly to communicate with them in a successful way [72].

The concept denominated “Food involvement” was another term reported in the bibliometric mapping. Sommers et al. [75] investigated this concept that is characterized as “the level of importance of food in a person’s life” [75]. Pleasure was found to be positively correlated with “food involvement” [75]. Additionally, studies suggest that higher perceived stress is positively related with unhealthy eating habits such as high intakes of saturated fats and sugars, further highlighting the importance to emphasize pleasurable aspects of eating to motivate older adults to follow healthy diets [75, 76].

Research Between 2015–2020 Assessed Social Determinants, the Effect of Previous Experiences on Food Choice and Barriers to Follow Government Nutritional Guidelines

When exploring the last cluster of publications, “dental status” was once again a frequent term among literature. There was a focus on micronutrient intake that was significantly lower among denture wearers without any natural dentition [77]. “Education” and other socio-demographic factors were, once more, recurring themes. Several studies, suggest that commonly, highly educated older adults tend to follow or adopt healthier dietary patterns [13, 78–83].

“Motive” was another term frequently present in the most recent literature. In a study performed by Rempe et al. [84], the so called “Eating Motivation Survey” was applied to determine these motivations in older adults [84]. According to the results of this study, “Health”, “Natural concerns” and “Weight control” are among the greatest food choice influences [84]. In a study by Bardach et al. [85], older adults were asked which factors would be important for them to change their nutrition and physical activity behavior. The study revealed three main individual factors: “perceptions of old age, personal motivation and perceived confidence in ability to make effective changes” [85]. It has been discussed that it is likely that older adults with health impairments that experienced the benefits of improving health behaviors are more motivated to follow a healthy diet than the ones that do not feel that an improvement is possible [85]. Employing the ‘Extended Parallel Process Model’ it was pointed out that if individuals do not believe that they can respond to a threat (e.g., health decline due to older age) they will come to terms with it instead of trying to aim for a change [85].

“Social relationship” was also among the frequent terms in the literature mapping. Rugel and Carpiano [86] hypothesize that emotional and informational support may enhance women’s motivation to eat in a healthy way by increasing their perception of self-efficacy and sense of purpose. A lack of social relationships, particularly when associated with low economic resources appeared to influence eating behavior in older adults, especially men, in a study performed in the United Kingdom [87]. A group of older adults living in a rural area reported “community support” to be of major importance in their food choices [88]. In fact, family influence was found to positively impact the consumption of fruit and vegetables among a group of older adults from the United States [89]. Participants were familiar with food sharing and trading with friends and family; peers were often relied upon as source of assistance [88, 90].

“Guideline” was another term appearing in the bibliometric mapping of publications between 2015 and 2020. It seems that participants from lower socio-economic status perceive more barriers to follow nutritional guidelines [80]. The high price of healthy foods is often referred to as a barrier for their consumption [80, 82]. Besides, sensory appeal is mentioned in literature as important for food choice [91]. It seems that disliking healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables constitutes a barrier for their consumption by older adults, particularly, the ones with lower incomes [80, 91].

“Childhood” was another frequent term found in literature published in this period. Studies suggest that in older men, an important factor that seems to influence food choice are childhood experiences [92]. This agrees with the findings reported above regarding the influence of life-course experiences on the eating behavior of the elderly. Traditional and familiar foods, often resulting from family habits and other life-course experiences, have been shown to be the preferred foods for the majority of older adults [88, 90]. Despite this, in recent years, the food industry has started the development of novel foods adapted to the needs of older adults e.g., being of softer consistencies and fortified; however, these kind of products may not be well accepted due to the stigmatization and even difficulty accepting new foods—food neophobia [93].

After 2010 Some Studies Investigated (Physical) Barriers for Healthy Eating

A physical determinant that affects the characteristics of food environments and food choices of older adults is the difference between rural and urban settings [94]. Epidemiological studies suggest that in rural settings older adults often suffer from limited infrastructures which hinders their access to healthy food [59, 61]. Studies also suggest that transportation reliability is an important factor for accessing food/food related programs [61, 63]. It is frequently mentioned by the elderly that cheaper food shops are not accessible to them, particularly for the ones that have impaired mobility [59, 61]. The characteristics of the place of residence, including the type of foods available, cost and proximity or availability of transport to food shops, seem to influence the food consumption of older adults [59, 63, 67, 94]. Furthermore, the environment where older adults prepare and eat their meals is also of relevance [95]. A study performed by Provencher et al. [95], reported that the elderly scored better at heating soup and cutting fruit at their own homes when compared to a kitchen in a clinic. Regarding community initiatives such as meal provision and government assistance, it was reported that low participation may result from lack of knowledge and stigma around these initiatives [88, 90, 94]. The fact that meals may not be tasteful or culturally sensitive has also been reported to lead to a lower utilization of these services [63].

Suggestions for Nutrition Communication Strategies

Several studies suggest that communication strategies need to be culturally tailored [82, 89]. A study performed by Howell [89] reported that the socio-cultural environment has a high influence on personal beliefs and attitudes towards diet. Moreover, studies suggest that the socio-cultural environment may widely vary between countries [46, 82, 89]. However, different neighborhoods may also need adapted communication strategies. A cross-sectional study from the United Kingdom investigated the influence on food choice of measures as food retail diversity, transport provision, marketing of unhealthy food and physical infrastructures that may affect mobility for older people [96]. In this study it was reported that “area (income) deprivation” is associated with the intake of fruit and vegetables among elderly [96].

Studies suggest that nutrition messages should be clear, short and targeted to the needs of specific target groups [59]. It further has been suggested that public policy interventions meant to improve the food choices of older adults should not only communicate the importance of maintaining a healthy diet but be actionable, explaining which actions can be taken by the elderly [97]. “Standalone” communication about healthy eating have been reported to be less effective than desired, but rather communication employing practical actions (e.g., nutrition workshops) may be more effective [59, 82]. Furthermore, it has been shown that interventions should focus on targeting older adults’ distrust of information sources such as food labels and media channels [74]. Additionally, it has been proposed that it is important to include the elderly in nutrition policy discussions in a citizen science approach, allowing them to share their perspectives [98].

Translation to Practical Communication Strategies

• Adapt for sex differences as older women and men typically eat differently and may even have differences in socioeconomic status.

• Consider hedonic characteristics of food simultaneously with practical matters as cost.

• Recognize oral health and other physiological impairments common at old age.

• Do not only communicate the importance of maintaining a healthy diet but explain which actions can be taken to achieve this.

• Create culturally tailored strategies, adapted by country and culture.

• Explore opportunities and barriers for using different communication channels, including digital channels.

• Use citizen science approaches in which older adults are included in the creation of communication strategies.

• Be dynamic and sensitive for changes in the food environment, it is essential to understand the past to target eating behavior in the present.

Conclusion and Future Research

Research about ecological determinants of eating behavior in older adults has evolved over time, leading to a holistic view of behavior including all ecological levels. As summarized in this review, studies have reported that within this age group there are differences regarding culture, living environment and socio-demographic characteristics. These have been proposed to shape older adults’ food choice. While various theories have been developed to explain eating behavior for different age groups, for elderly, tailored measures to communicate healthy nutrition are still limited. It is important to explore the perspective of elderly towards their own behaviors and consider how to target external barriers for healthy eating.

We live in a constantly changing society; hence it is important to understand how to use the available communication resources to improve the health of this growing segment in society.

Research about eating behavior in the elderly, and ecological determinants that influence it, is crucial to achieve health and quality of life in this group. As the food environment evolve throughout the years, future research should stay updated about how various periods and events affect older adults. This will help to gain insights into the best strategies to communicate about nutrition with older adults with diverse backgrounds and modulate their eating behaviors towards healthier ones if needed.

Limitations

As data about the effects of the pandemic on the eating behavior of the elderly is still limited, this review only focused on the period before that. Furthermore, only studies performed in community-dwelling older adults were included in this review. This choice was made as targeting institutionalized elderly would require investigating different stakeholders and determinants. The age range of the elderly in the studies included in this review is quite variable, yet it was decided to consider each study’s definition of older adult, as the objective of this scoping review was to gather information as broad as possible. Lastly, although an internal review protocol was elaborated, this was not registered in any open platform.

Strengths

It is challenging to deliver an understandable “picture” of the determinants of eating behavior in the elderly. Here, both a-priori and a-posteriori analyses were performed with the support of graphical representations to explore determinants of eating behavior in a holistic way, thereby creating a basis for the development of nutrition communication strategies focusing on this group. Based on an in-depth analysis of the literature, this review provides advice for the development of nutrition communication strategies for the elderly. It is important to acknowledge that the topic of this review is dynamic, hence it is necessary to capture past influences in eating behavior to understand the present and make future predictions. This was done by splitting the literature into periods and analyzing patterns emerging in those.

Author Contributions

ÍM and CB were responsible for the conception and design of the present research. ÍM is responsible for the acquisition of data through the literature search, the initial analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript. CB gave crucial suggestions for the improvement of the methods used. CB and IB were responsible for critically revising the manuscript and giving crucial suggestions regarding the content. All authors gave their final approval.

Funding

The authors declare that this project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 859890 (Innovative Training Network SmartAge). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of John Bennett in proof-reading the manuscript. This review is integrated in the Innovative Training Network SmartAge, with the aim of adding to a better understanding of the gut-brain-axis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2022.1604967/full#supplementary-material

References

1.European Commission. Active Ageing - Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion (2021). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=1062 (Assessed May 17, 2021).

2. Rudnicka, E, Napierała, P, Podfigurna, A, Męczekalski, B, Smolarczyk, R, and Grymowicz, M. The World Health Organization (WHO) Approach to Healthy Ageing. Maturitas (2020). 139:6–11. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.018

3.Eurostat. Ageing Europe - Statistics on Health and Disability (2020). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Ageing_Europe_-_statistics_on_health_and_disability (Assessed May 18, 2021).

4. Yannakoulia, M, Mamalaki, E, Anastasiou, CA, Mourtzi, N, Lambrinoudaki, I, and Scarmeas, N. Eating Habits and Behaviors of Older People: Where are We Now and Where Should We Go? Maturitas (2018). 114:14–21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.05.001

5. Bukman, AJ, Ronteltap, A, and Lebrun, M. Interpersonal Determinants of Eating Behaviours in Dutch Older Adults Living Independently: A Qualitative Study. BMC Nutr (2020). 6:55. doi:10.1186/s40795-020-00383-2

6. Lesáková, D. Health Perception and Food Choice Factors in Predicting Healthy Consumption Among Elderly. Acta Univ Agric Silvic Mendelianae Brun (2018). 66:1527–34. doi:10.11118/actaun201866061527

7. Robinson, SM. Improving Nutrition to Support Healthy Ageing: What are the Opportunities for Intervention? Proc Nutr Soc (2018). 77:257–64. doi:10.1017/S0029665117004037

8. Salazar, N, Valdés-Varela, L, González, S, Gueimonde, M, and de los Reyes-Gavilán, CG. Nutrition and the Gut Microbiome in the Elderly. Gut Microbes (2017). 8:82–97. doi:10.1080/19490976.2016.1256525

9. Pray, L, Boon, C, Miller, EA, and Pillsbury, L. Providing Healthy and Safe Foods as We Age: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2010). p. 113–4p.

10. Kok, G, Gottlieb, NH, Commers, M, and Smerecnik, C. The Ecological Approach in Health Promotion Programs: A Decade Later. Am J Health Promot (2008). 22:437–42. doi:10.4278/ajhp.22.6.437

11. Caperon, L, Arjyal, A, Puja, KC, Kuikel, J, Newell, J, Peters, R, et al. Developing a Socio-Ecological Model of Dietary Behaviour for People Living with Diabetes or High Blood Glucose Levels in Urban Nepal: A Qualitative Investigation. PLoS ONE (2019). 14:e0214142. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214142

12. Story, M, Kaphingst, KM, Robinson-O'Brien, R, and Glanz, K. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu Rev Public Health (2008). 29:253–72. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926

13. Shatenstein, B, Gauvin, L, Keller, H, Richard, L, Gaudreau, P, Giroux, F, et al. Individual and Collective Factors Predicting Change in Diet Quality over 3 Years in a Subset of Older Men and Women from the NuAge Cohort. Eur J Nutr (2016). 55:1671–81. doi:10.1007/s00394-015-0986-y

14. Swan, E, Bouwman, L, Aarts, N, Rosen, L, Hiddink, GJ, and Koelen, M. Food Stories: Unraveling the Mechanisms Underlying Healthful Eating. Appetite (2018). 120:456–63. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.005

15. Golden, SD, and Earp, JAL. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts: Twenty Years of Health Education & Behavior Health Promotion Interventions. Health Educ Behav (2012). 39:364–72. doi:10.1177/1090198111418634

16. Payette, H, and Shatenstein, B. Determinants of Healthy Eating in Community-Dwelling Elderly People. Can J Public Health Rev Can Sante Publ (2005). 96(Suppl. 3S27-31):S30–35. doi:10.1007/bf03405198

17. Dunneram, Y, and Jeewon, R. Determinants of Eating Habits Among Older Adults. Prog Nutr (2015). 17(4):274–83. doi:10.11648/j.ijnfs.20130203.13

18. Mohd Shahrin, FI, Omar, N, Omar, N, Mat Daud, ZA, and Zakaria, NF. Factors Associated with Food Choices Among Elderly: A Scoping Review. Mal J Nutr (2019). 25(2):185–98. doi:10.31246/mjn-2018-0133

19. Herne, S. Research on Food Choice and Nutritional Status in Elderly People: A Review. Br Food J (1995). 97(9):12–29. doi:10.1108/00070709510100136

20. Schneider, T, Eli, K, Dolan, C, and Ulijaszek, S. Digital Food Activism. London: Routledge (2018). p. 252.

21. Host, A, McMahon, A-T, Walton, K, and Charlton, K. Factors Influencing Food Choice for Independently Living Older People-A Systematic Literature Review. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr (2016). 35:67–94. doi:10.1080/21551197.2016.1168760

22. García, T, and Grande, I. Determinants of Food Expenditure Patterns Among Older Consumers. The Spanish Case. Appetite (2010). 54:62–70. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2009.09.007

23. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med (2018). 169:467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

24. Arksey, H, and O'Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2005). 8:19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

25. van Eck, NJ, and Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics (2010). 84:523–38. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

26. McDonald, J, Quandt, SA, Arcury, TA, Bell, RA, and Vitolins, MZ. On Their Own: Nutritional Self-Management Strategies of Rural Widowers. Gerontologist (2000). 40:480–91. doi:10.1093/geront/40.4.480

27. de Almeida, MD, Graça, P, Afonso, C, Kearney, JM, and Gibney, MJ. Healthy Eating in European Elderly: Concepts, Barriers and Benefits. J Nutr Health Aging (2001). 5:217–9.

28. Kim, K, Reicks, M, and Sjoberg, S. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Dairy Product Consumption by Older Adults. J Nutr Edu Behav (2003). 35:294–301. doi:10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60343-6

29. Sindler, AJ, Wellman, NS, and Stier, OB. Holocaust Survivors Report Long-Term Effects on Attitudes toward Food. J Nutr Edu Behav (2004). 36:189–96. doi:10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60233-9

30. Tucker, M, and Reicks, M. Exercise as a Gateway Behavior for Healthful Eating Among Older Adults: An Exploratory Study. J Nutr Edu Behav (2002). 34(Suppl. 1):S14–S19. doi:10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60306-0

31. Pryer, JA, Cook, A, and Shetty, P. Identification of Groups Who Report Similar Patterns of Diet Among a Representative National Sample of British Adults Aged 65 Years of Age or More. Public Health Nutr (2001). 4:787–95. doi:10.1079/PHN200098

32. Österberg, T, Tsuga, K, Rothenberg, E, Carlsson, GE, and Steen, B. Masticatory Ability in 80-Year-Old Subjects and its Relation to Intake of Energy, Nutrients and Food Items. Gerodontology (2002). 19:95–101. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2002.00095.x

33. Vitolins, MZ, Quandt, SA, Bell, RA, Arcury, TA, and Case, LD. Quality of Diets Consumed by Older Rural Adults. J Rural Health (2002). 18:49–56. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00876.x

34. Callen, BL, and Wells, TJ. Views of Community-Dwelling, Old-Old People on Barriers and Aids to Nutritional Health. J Nurs Scholarship (2003). 35:257–62. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00257.x

35. Palmer, CA. Gerodontic Nutrition and Dietary Counseling for Prosthodontic Patients. Dental Clin North Am (2003). 47:355–71. doi:10.1016/s0011-8532(02)00104-0

36. Johnson, CS, and Garcia, AC. Dietary and Activity Profiles of Selected Immigrant Older Adults in Canada. J Nutr Elder (2003). 23:23–39. doi:10.1300/J052v23n01_02

37. Haveman-Nies, A, Tucker, K, de Groot, L, Wilson, P, and Van Staveren, W. Evaluation of Dietary Quality in Relationship to Nutritional and Lifestyle Factors in Elderly People of the US Framingham Heart Study and the European SENECA Study. Eur J Clin Nutr (2001). 55:870–80. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601232

38. van Rossum, C, van de Mheen, H, Witteman, J, Grobbee, E, and Mackenbach, J. Education and Nutrient Intake in Dutch Elderly People. The Rotterdam Study. Eur J Clin Nutr (2000). 54:159–65. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600914

39. Corrêa Leite, ML, Nicolosi, A, Cristina, S, Hauser, WA, Pugliese, P, and Nappi, G. Dietary and Nutritional Patterns in an Elderly Rural Population in Northern and Southern Italy: (I). A Cluster Analysis of Food Consumption. Eur J Clin Nutr (2003). 57:1514–21. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601719

40. Rurik, I. Evaluation on Lifestyle and Nutrition Among Hungarian Elderly. Z Gerontol Geriatr (2004). 37:33–6. doi:10.1007/s00391-004-0152-2

41. de Castro, JM. Age-related Changes in the Social, Psychological, and Temporal Influences on Food Intake in Free-Living, Healthy, Adult Humans. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci (2002). 57:M368–M377. doi:10.1093/gerona/57.6.m368

42. Rurik, I. Nutritional Differences between Elderly Men and Women. Primary Care Evaluation in Hungary. Ann Nutr Metab (2006). 50:45–50. doi:10.1159/000089564

43. Shannon, J, Shikany, J, Barrett-Connor, E, Marshall, L, Bunker, C, Chan, J, et al. Demographic Factors Associated with the Diet Quality of Older US Men: Baseline Data from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study. Public Health Nutr (2007). 10:810–8. doi:10.1017/S1368980007258604

44. Dean, M, Raats, MM, Grunert, KG, and Lumbers, M. Factors Influencing Eating a Varied Diet in Old Age. Public Health Nutr (2009). 12:2421–7. doi:10.1017/S1368980009005448

45. Hunter, W, and Worsley, T. Understanding the Older Food Consumer. Present Day Behaviours and Future Expectations. Appetite (2009). 52:147–54. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.007

46. Savoca, MR, Arcury, TA, Leng, X, Bell, RA, Chen, H, Anderson, A, et al. The Diet Quality of Rural Older Adults in the South as Measured by Healthy Eating index-2005 Varies by Ethnicity. J Am Diet Assoc (2009). 109:2063–7. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.005

47. Ervin, RB. Healthy Eating Index Scores Among Adults, 60 Years of Age and over, by Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics: United States, 1999-2002. Adv Data (2008) 395, 1–16.

48. Smith, SL, Quandt, SA, Arcury, TA, Wetmore, LK, Bell, RA, and Vitolins, MZ. Aging and Eating in the Rural, Southern United States: Beliefs about Salt and its Effect on Health. Soc Sci Med (2006). 62:189–98. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.009

49. Tannenbaum, C, and Shatenstein, B. Exercise and Nutrition in Older Canadian Women: Opportunities for Community Intervention. Can J Public Health (2007). 98:187–93. doi:10.1007/BF03403710

50. Walker, SN, Pullen, CH, Hertzog, M, Boeckner, L, and Hageman, PA. Determinants of Older Rural Women's Activity and Eating. West J Nurs Res (2006). 28:449–68. doi:10.1177/0193945906286613

51. Martin, CT, Kayser-Jones, J, Stotts, NA, Porter, C, and Froelicher, ES. Factors Contributing to Low Weight in Community-Living Older Adults. J Amer Acad Nurse Pract (2005). 17:425–31. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2005.00073.x

52. Payne, ME, Hybels, CF, Bales, CW, and Steffens, DC. Vascular Nutritional Correlates of Late-Life Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry (2006). 14:787–95. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000203168.28872.21

53. Giltay, EJ, Geleijnse, JM, Zitman, FG, Buijsse, B, and Kromhout, D. Lifestyle and Dietary Correlates of Dispositional Optimism in Men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. J Psychosomatic Res (2007). 63:483–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.014

54. Ervin, RB, and Dye, BA. The Effect of Functional Dentition on Healthy Eating Index Scores and Nutrient Intakes in a Nationally Representative Sample of Older Adults. J Public Health Dent (2009). 69:207–16. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00124.x

55. Savoca, MR, Arcury, TA, Leng, X, Chen, H, Bell, RA, Anderson, AM, et al. Association between Dietary Quality of Rural Older Adults and Self-Reported Food Avoidance and Food Modification Due to Oral Health Problems. J Am Geriatr Soc (2010). 58:1225–32. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02909.x

56. Quandt, SA, Savoca, MR, Leng, X, Chen, H, Bell, RA, Gilbert, GH, et al. Dry Mouth and Dietary Quality in Older Adults in north Carolina. J Am Geriatr Soc (2011). 59:439–45. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03309.x

57. Ford, DW, Hartman, TJ, Still, C, Wood, C, Mitchell, D, Hsiao, PY, et al. Diet-related Practices and BMI are Associated with Diet Quality in Older Adults. Public Health Nutr (2014). 17:1565–9. doi:10.1017/S1368980013001729

58. Bethene Ervin, R, and Dye, BA. Number of Natural and Prosthetic Teeth Impact Nutrient Intakes of Older Adults in the United States. Gerodontology (2012). 29:e693–e702. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00546.x

59. Best, RL, and Appleton, KM. The Consumption of Protein-Rich Foods in Older Adults: An Exploratory Focus Group Study. J Nutr Edu Behav (2013). 45:751–5. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.03.008

60. Shatenstein, B, Gauvin, L, Keller, H, Richard, L, Gaudreau, P, Giroux, F, et al. Baseline Determinants of Global Diet Quality in Older Men and Women from the NuAge Cohort. J Nutr Health Aging (2013). 17:419–25. doi:10.1007/s12603-012-0436-y

61. Nicklett, EJ, and Kadell, AR. Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Maturitas (2013). 75:305–12. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.005

62. Mobley, AR, Jensen, JD, and Maulding, MK. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Barriers Related to Milk Consumption in Older, Low-Income Women. J Nutr Edu Behav (2014). 46:554–9. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.11.018

63. Munoz-Plaza, CE, Morland, KB, Pierre, JA, Spark, A, Filomena, SE, and Noyes, P. Navigating the Urban Food Environment: Challenges and Resilience of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J Nutr Edu Behav (2013). 45:322–31. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.01.015

64. Huy, C, Schneider, S, and Thiel, A. Perceptions of Aging and Health Behavior: Determinants of a Healthy Diet in an Older German Population. J Nutr Health Aging (2010). 14:381–5. doi:10.1007/s12603-010-0084-z

65. Dijkstra, SC, Neter, JE, Brouwer, IA, Huisman, M, and Visser, M. Motivations to Eat Healthily in Older Dutch Adults - A Cross Sectional Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2014). 11:141. doi:10.1186/s12966-014-0141-9

66. Irz, X, Fratiglioni, L, Kuosmanen, N, Mazzocchi, M, Modugno, L, Nocella, G, et al. Sociodemographic Determinants of Diet Quality of the EU Elderly: A Comparative Analysis in Four Countries. Public Health Nutr (2014). 17:1177–89. doi:10.1017/S1368980013001146

67. Tyrovolas, S, Haro, JM, Mariolis, A, Piscopo, S, Valacchi, G, Tsakountakis, N, et al. Successful Aging, Dietary Habits and Health Status of Elderly Individuals: A K-Dimensional Approach within the Multi-National MEDIS Study. Exp Gerontol (2014). 60:57–63. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2014.09.010

68. Harrington, JM, Dahly, DL, Fitzgerald, AP, Gilthorpe, MS, and Perry, IJ. Capturing Changes in Dietary Patterns Among Older Adults: A Latent Class Analysis of an Ageing Irish Cohort. Public Health Nutr (2014). 17:2674–86. doi:10.1017/S1368980014000111

69. Conklin, AI, Forouhi, NG, Suhrcke, M, Surtees, P, Wareham, NJ, and Monsivais, P. Variety More Than Quantity of Fruit and Vegetable Intake Varies by Socioeconomic Status and Financial Hardship. Findings from Older Adults in the EPIC Cohort. Appetite (2014). 83:248–55. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.038

70. Giuli, C, Papa, R, Mocchegiani, E, and Marcellini, F. Dietary Habits and Ageing in a Sample of Italian Older People. J Nutr Health Aging (2012). 16:875–9. doi:10.1007/s12603-012-0080-6

71. Dijkstra, SC, Neter, JE, Brouwer, IA, Huisman, M, and Visser, M. Adherence to Dietary Guidelines for Fruit, Vegetables and Fish Among Older Dutch Adults; the Role of Education, Income and Job Prestige. J Nutr Health Aging (2014). 18(2):115–21. doi:10.1007/s12603-013-0402-3

72. Lundkvist, P, Fjellström, C, Sidenvall, B, Lumbers, M, and Raats, M. Management of Healthy Eating in Everyday Life Among Senior Europeans. Appetite (2010). 55:616–22. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.015

73. Mõttus, R, McNeill, G, Jia, X, Craig, LCA, Starr, JM, and Deary, IJ. The Associations between Personality, Diet and Body Mass index in Older People. Health Psychol (2013). 32:353–60. doi:10.1037/a0025537

74. Vella, MN, Stratton, LM, Sheeshka, J, and Duncan, AM. Functional Food Awareness and Perceptions in Relation to Information Sources in Older Adults. Nutr J (2014). 13:44. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-44

75. Somers, J, Worsley, A, and McNaughton, SA. The Association of Mavenism and Pleasure with Food Involvement in Older Adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2014). 11:60. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-11-60

76. Barrington, WE, Beresford, SAA, McGregor, BA, and White, E. Perceived Stress and Eating Behaviors by Sex, Obesity Status, and Stress Vulnerability: Findings from the Vitamins and Lifestyle (VITAL) Study. J Acad Nutr Diet (2014). 114:1791–9. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2014.03.015

77. Watson, S, McGowan, L, McCrum, L-A, Cardwell, CR, McGuinness, B, Moore, C, et al. The Impact of Dental Status on Perceived Ability to Eat Certain Foods and Nutrient Intakes in Older Adults: Cross-Sectional Analysis of the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey 2008-2014. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2019). 16:43. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0803-8

78. Allès, B, Samieri, C, Lorrain, S, Jutand, M-A, Carmichael, P-H, Shatenstein, B, et al. Nutrient Patterns and Their Food Sources in Older Persons from France and Quebec: Dietary and Lifestyle Characteristics. Nutrients (2016). 8:225. doi:10.3390/nu8040225

79. Granic, A, Davies, K, Adamson, A, Kirkwood, T, Hill, TR, Siervo, M, et al. Dietary Patterns and Socioeconomic Status in the Very Old: The Newcastle 85+ Study. PLoS One (2015). 10:e0139713. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139713

80. Dijkstra, SC, Neter, JE, van Stralen, MM, Knol, DL, Brouwer, IA, Huisman, M, et al. The Role of Perceived Barriers in Explaining Socio-Economic Status Differences in Adherence to the Fruit, Vegetable and Fish Guidelines in Older Adults: A Mediation Study. Public Health Nutr (2015). 18:797–808. doi:10.1017/S1368980014001487

81. Andreeva, V, Allès, B, Feron, G, Gonzalez, R, Sulmont-Rossé, C, Galan, P, et al. Sex-Specific Sociodemographic Correlates of Dietary Patterns in a Large Sample of French Elderly Individuals. Nutrients (2016). 8:484. doi:10.3390/nu8080484

82. Hung, Y, Wijnhoven, H, Visser, M, and Verbeke, W. Appetite and Protein Intake Strata of Older Adults in the European Union: Socio-Demographic and Health Characteristics, Diet-Related and Physical Activity Behaviours. Nutrients (2019). 11:777. doi:10.3390/nu11040777

83. Mumme, K, Conlon, C, von Hurst, P, Jones, B, Stonehouse, W, Heath, A-LM, et al. Dietary Patterns, Their Nutrients, and Associations with Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle Factors in Older New Zealand Adults. Nutrients (2020). 12:3425. doi:10.3390/nu12113425

84. Rempe, HM, Sproesser, G, Gingrich, A, Spiegel, A, Skurk, T, Brandl, B, et al. Measuring Eating Motives in Older Adults with and without Functional Impairments with the Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS). Appetite (2019). 137:1–20. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2019.01.024

85. Bardach, SH, Schoenberg, NE, and Howell, BM. What Motivates Older Adults to Improve Diet and Exercise Patterns? J Community Health (2016). 41:22–9. doi:10.1007/s10900-015-0058-582

86. Rugel, EJ, and Carpiano, RM. Gender Differences in the Roles for Social Support in Ensuring Adequate Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Older Adult Canadians. Appetite (2015). 92:102–9. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.05.011

87. Conklin, AI, Forouhi, NG, Surtees, P, Wareham, NJ, and Monsivais, P. Gender and the Double burden of Economic and Social Disadvantages on Healthy Eating: Cross-Sectional Study of Older Adults in the EPIC-Norfolk Cohort. BMC Public Health (2015). 15:692. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1895-y

88. Byker Shanks, C, Haack, S, Tarabochia, D, Bates, K, and Christenson, L. Factors Influencing Food Choices Among Older Adults in the Rural Western USA. J Community Health (2017). 42:511–21. doi:10.1007/s10900-016-0283-6

89. Howell, BM. Interactions between Diet, Physical Activity, and the Sociocultural Environment for Older Adult Health in the Urban Subarctic. J Community Health (2020). 45:252–63. doi:10.1007/s10900-019-00737-3

90. Oemichen, M, and Smith, C. Investigation of the Food Choice, Promoters and Barriers to Food Access Issues, and Food Insecurity Among Low-Income, Free-Living Minnesotan Seniors. J Nutr Edu Behav (2016). 48:397–404. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2016.02.010

91. Kamphuis, CB, de Bekker-Grob, EW, and van Lenthe, FJ. Factors Affecting Food Choices of Older Adults from High and Low Socioeconomic Groups: A Discrete Choice experiment. Am J Clin Nutr (2015). 101:768–74. doi:10.3945/ajcn.114.096776

92. Atkins, JL, Ramsay, SE, Whincup, PH, Morris, RW, Lennon, LT, and Wannamethee, SG. Diet Quality in Older Age: The Influence of Childhood and Adult Socio-Economic Circumstances. Br J Nutr (2015). 113:1441–52. doi:10.1017/S0007114515000604

93. van den Heuvel, E, Newbury, A, and Appleton, K. The Psychology of Nutrition with Advancing Age: Focus on Food Neophobia. Nutrients (2019). 11:151. doi:10.3390/nu11010151

94. Johnson, MA. Strategies to Improve Diet in Older Adults. Proc Nutr Soc (2013). 72:166–72. doi:10.1017/S0029665112002819

95. Provencher, V, Demers, L, and Gélinas, I. Factors that May Explain Differences between home and Clinic Meal Preparation Task Assessments in Frail Older Adults. Int J Rehabil Res (2012). 35:248–55. doi:10.1097/MRR.0b013e3283544cb8

96. Hawkesworth, S, Silverwood, RJ, Armstrong, B, Pliakas, T, Nanchahal, K, Sartini, C, et al. Investigating the Importance of the Local Food Environment for Fruit and Vegetable Intake in Older Men and Women in 20 UK Towns: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Two National Cohorts Using Novel Methods. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2017). 14:1–14. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0581-0

97. Brownie, S, and Coutts, R. Older Australians' Perceptions and Practices in Relation to a Healthy Diet for Old Age: A Qualitative Study. J Nutr Health Aging (2013). 17:125–9. doi:10.1007/s12603-012-0371-y

Keywords: food environment, ecological model, bibliometric analysis, eating behavior, community-dwelling elderly, nutrition communication

Citation: Montez De Sousa ÍR, Bergheim I and Brombach C (2022) Beyond the Individual -A Scoping Review and Bibliometric Mapping of Ecological Determinants of Eating Behavior in Older Adults. Public Health Rev 43:1604967. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604967

Received: 31 March 2022; Accepted: 27 June 2022;

Published: 03 August 2022.

Edited by:

Ana Ribeiro, University Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Cláudia Raquel Jardim Santos, University of Porto, PortugalJesús Rivera Navarro, University of Salamanca, Spain

Margarida Pereira, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway

Copyright © 2022 Montez De Sousa, Bergheim and Brombach. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Íris Rafaela Montez De Sousa, aXJpc21vbnRlemRlc291c2FAZ21haWwuY29t

This Review is part of the PHR Special Issue “Neighbourhood Influcences on Population Health”

Íris Rafaela Montez De Sousa

Íris Rafaela Montez De Sousa Ina Bergheim2

Ina Bergheim2