- Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Deonar, India

Objective: Population aging is an ongoing challenge for global health policy and is expected to have an increasing impact on developing economies in years to come. A variety of community health programs have been developed to deliver health services to older adults, and evaluating these programs is crucial to improving service delivery and avoiding barriers to implementation. This systematic review examines published evaluation research relating to public and community health programs aimed at older adults throughout the world.

Methods: A literature search using standardized criteria yielded 58 published articles evaluating 46 specific programs in 14 countries.

Results: Service models involving sponsorship of comprehensive facilities providing centralized access to multiple types of health services were generally evaluated the most positively, with care coordination programs appearing to have generally more modest success, and educational programs having limited effectiveness. Lack of sufficient funding was a commonly-cited barrier to successful program implementations.

Conclusion: It is important to include program evaluation as a component of future community and public health interventions aimed at aging populations to better understand how to improve these programs.

Introduction

The global population is aging rapidly, with the number of older adults worldwide projected to more than double in the coming decades to more than 1.5 billion [1]. The aging population is increasing in all 195 countries in the world, with the fastest rate of aging shifting away from Europe and North America and toward China and India [2]. These trends have important implications for public health, as the burden of diseases related to older age, ranging from cardiovascular disease [3], to cancer [4], to diabetes [5], to dementia [6], are expected to continue to increase. In addition to the impact of these public health challenges on population well-being, they are expected to cause substantial increases in public and private expenditures on health care [1]. The global burden of these increases in health care demand are likely to have the most severe impact on low and middle income countries with less developed health care infrastructures [7]. However, countries at all levels of development are fundamentally impacted, making it essential to address solutions at a global level. To improve population health and decrease the costs of medical care in late life, governments around the world have undertaken programs aimed at addressing the specific medical needs of older adults. The purpose of this study is to systematically review the empirical literature at the global level evaluating government-funded community health programs addressing the health of older adults.

The Demographic Transition Model and Global Population Aging

Population change is a function of the rates of birth and mortality [8]. Advances in medical care and public health over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries resulted in globally declining mortality rates, and consequently to exponential increases in the world population [9]. It is estimated that it took until the year 1800 for the global population to reach 1 billion people; the global population subsequently more than doubled in the next 150 years [9] and reached 7 billion by 2011 [10]. However, this growth has not been uniform throughout the world. Regions seeing the earliest decreases in mortality rates also began to see subsequent decreases in birth rates, such that net natural population growth has halted or turned to decline in much of the global North [9]. In the global South, where changes in the mortality rate accrued later due to long-term structural economic and material inequalities, changes in birth rates have only started to begin to change [11]. As a result, it is estimated that the global population will reach a maximum of approximately 11 billion by the year 2100, before declining as the global birth rate falls below the global death rate [12].

In the interim, these population dynamics dictate that the age composition of the population is unequal between regions globally and remains in a state of long-term change throughout the world. These patterns have been identified for many decades and are collectively known as the demographic transition model [8]. In particular, the combination of declining birth rate and increasing life span in the global North has led to dramatic population aging, with the number of older adults exceeding the number of young people in some areas [9]. Meanwhile, a combination of falling mortality, rising life expectancy, and continued high birth rates in the global South have resulted in a sustained period of high population growth in these regions, with very young median ages [11]. The result has been countervailing population pressures in these two global regions. The large number of older adults relative to younger and middle adults in the global North has created a high dependency ratio, with relatively few working-age adults to support the population of pensioners, placing significant strain on social service and health care budgets [9]. In the global South, the large population of younger adults has created strains on educational and economic resources [13]. A result has been substantial population migration from the global South to the global North [12].

As demographic trends continue to evolve, new sources of strain can be anticipated. As inequalities in access to medical and educational resources in the global South have begun to be levelled, so too has the birth rate in these regions begun to decline, in a reflection of trends seen in previous generations in the global North [9, 12]. Thus, it can be anticipated that population aging will follow an analogous trajectory in these regions [14], with similar implications for increasing burdens of health care expenditures. Countries faced with the expectancy of these transitions have an interest in developing solutions to reduce the health care burdens associated with an aging population. For example, India began implementing the National Programme for the Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) during the last decade to provide integrated medical services to older adults through funding facilities improvements at the regional level [15]. The aim of this study is to systematically review all available evaluation studies of government-funded community health programs for older adults implemented. Based on the demographic transition model, it is anticipated that adoption of such programs in the global South has increased in recent years.

Methods

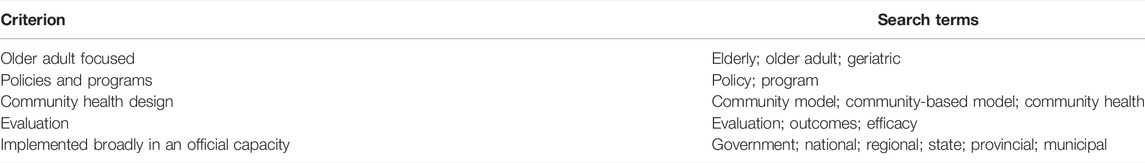

A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard, which were initially established in 2009 and has been endorsed by a large body of scientific journals and editorial consortia [16]. To identify qualifying publications, a literature search was conducted using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles were included in the review if they 1) reported on the evaluation of one or more community health programs 2) carried out by or with the support of a governmental body at the local, regional, or national level and 3) specifically serving an older adult population, and that 4) were published in English 5) between 2000 and December 31, 2020. Reports on single-institution clinical studies were excluded. Excluded item types included 1) theses or dissertations, 2) conference abstracts and proceedings, 3) theoretical papers, 4) comments or letters to the editor, and 5) previous reviews. To identify qualifying articles, a literature search was conducted in Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct, using a combination of search criteria specifying the scope each element of the review (see Table 1). These three databases were used because they collectively index of more than 30,000 journals in the medical and social sciences, providing comprehensive coverage of the relevant published literature.

Results

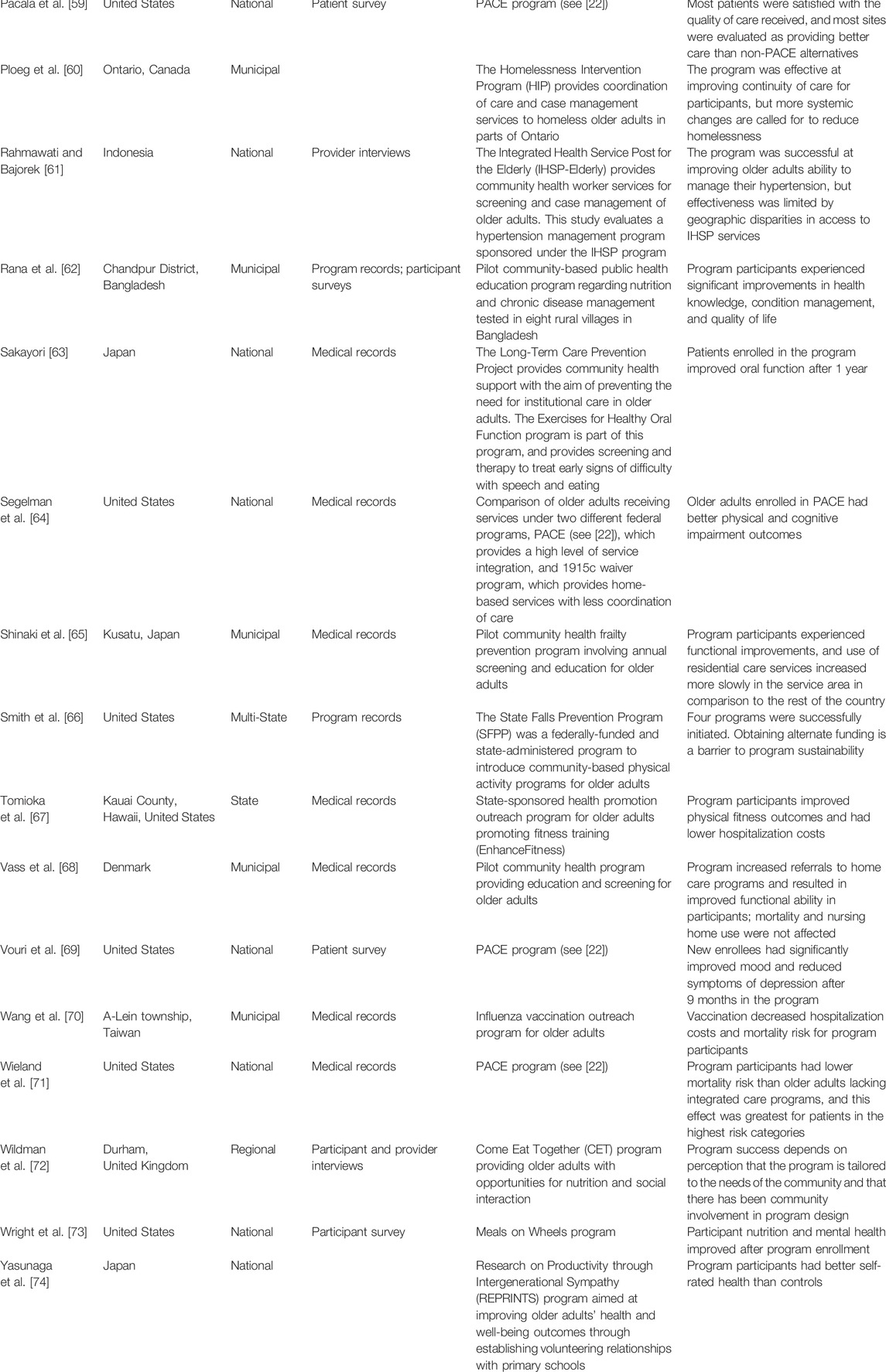

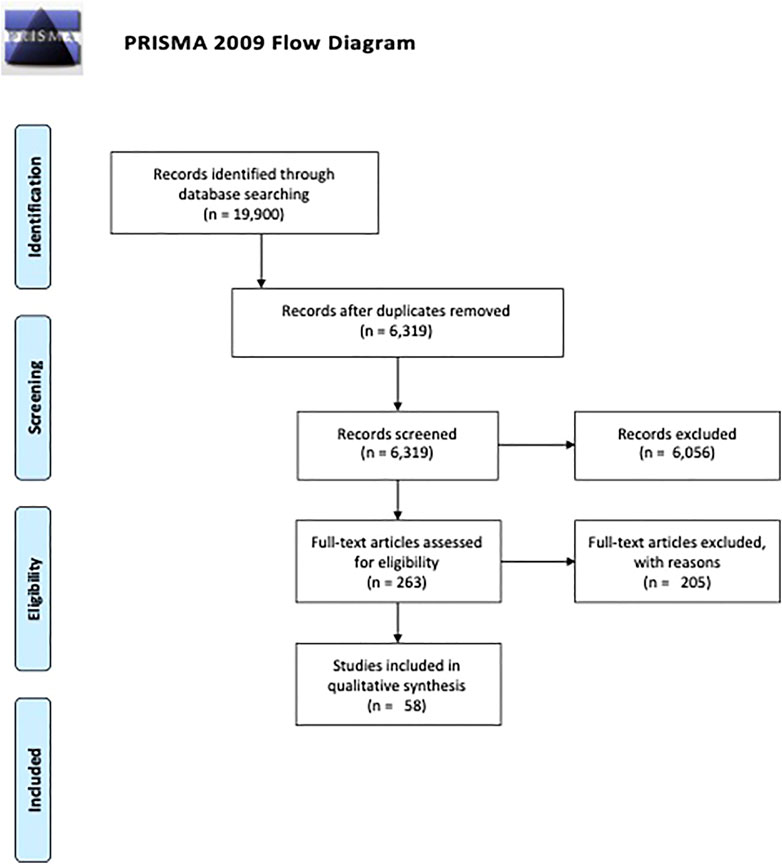

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the literature search and screening process. From an initial pool of 19,900 search results, a final sample of 58 articles meeting all of the review criteria were identified and included in this review. Details and key findings of these studies are summarized in Table 2. In terms of geography, 22 studies evaluated programs located in the United States (37.9%), 9 in Japan (15.5%), 6 were in Canada (10.3%), 3 each in Taiwan and Denmark (5.2% each), 2 each in Brazil, China, Indonesia, and Netherlands (3.5% each), and 1 each in Australia, Bangladesh, Mexico, Sweden, and United Kingdom (1.7% each). In terms of program scope, 23 were conducted at the community level (40.4%), 17 at the national level (29.3%), 11 at the State or Provincial level (19.3%), and 7 at the regional level (12.3%).

FIGURE 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses flow diagram (Global, 2000–2020).

A diverse range of evaluation methodologies were employed, with some studies implementing multiple evaluation techniques. The most commonly used evaluation tool was review of participant medical records to examine whether or not program participants had lower demand for health services and/or better health outcomes in comparison to others; this methodology was applied in 13 studies (22.4%). Other common methodologies included participant surveys (11 studies, 19.0%), program record reviews (10 studies, 17.2%), provider interviews (8 studies, 13.8%), and participant interviews (6 studies, 10.3%). Other studies employed prospective designs to evaluate pilot programs using randomized controlled trials (4 studies, 6.9%) or a case-control comparison with matched communities (4 studies, 6.9%). Six studies were primarily descriptive and enumerated program successes and failures without necessarily employing a formal evaluation methodology (10.3%). Other studies used economic analysis (4 studies, 6.9%), public opinion surveys including non-participants as well as program participants (2 studies, 3.5%), and examination of community-level health outcomes (2 studies, 3.5%).

Some programs were evaluated by multiple studies. In particular, 7 articles [17–23] addressed the PACE program, which is a longstanding federally sponsored health program in the US that encourages the establishment of coordinated care services for older adults. Several other programs were evaluated by two studies each, including the US Meals on Wheels program [24, 25], the Community Care Centres Plan (CCCP) in Taiwan [26, 27], the Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) in Ontario [28, 29], the Agita Sao Paulo Program in Brazil [30, 31], the Frailty Portal program in Nova Scotia [32, 33], and the Healthy Aging program in the Netherlands [34, 35]. In the last four of these cases, this represented an early descriptive evaluation of the program, followed by a second more formal evaluation.

The approach and range of services offered by the evaluated programs was very diverse. The most comprehensive programs were designed to establish centers providing comprehensive health care for older adults, usually with the goals of reducing the need for emergency medical intervention and allowing older adults to receive care in their own homes for as long as possible, rather than requiring residential nursing home care. There was a total of 9 studies examining these programs, including 8 addressing the PACE program in the US and 1 addressing the POSA program in Italy. Other programs with similar aims were designed to coordinate care between multiple existing health care and social service providers, rather than combining these services under the authority of a single center. There were also 9 studies of programs of this type, including 3 in the US, 3 in Canada, 2 in Japan, and 1 in Australia. A program based in Mexico was designed to facilitate coordination of care through the use of volunteer peer health navigators [36]. A conceptually related type of program aimed to create senior activity centers providing a combination of recreational, social, and health care services for older adults. Programs of this type were evaluated by studies located in Taiwan [26, 27] and Indonesia [37]. The distribution of countries represented here was derived from the literature search as described above, and represents the programs with qualifying published evaluations.

Other community health programs with more limited scope included health visitation and screening programs [38–43], mental health service programs [44], vaccination programs [45, 46], meal programs [24, 25, 47], and prevention of specific health problems including falls [48–51], hypertension [37, 52], and suicide [53]. Finally, less comprehensive and time-limited community health programs including education and fitness classes accounted for 18 of the programs evaluated (31.0%).

Discussion

This review highlights two important elements of community health intervention for older adults: the extent of program implementation throughout the globe, and the application of evaluation frameworks to these programs. Regarding the first issue, it is clear that governmental authorities throughout the world have acknowledged the importance of implementing programs aimed at serving the older adult population as a key element of addressing the challenges of population aging. The programs covered by the evaluations reviewed here represent five continents, including both developed and developing economies. Many of these programs are clustered in countries where population aging has been a longstanding concern, including Japan, Italy, Canada, and the US. Countries with younger populations tend to have less developed economies [1], making it difficult to determine whether the under-representation of these countries in the evaluations covered in this review may be due to prioritization of health promotion for other populations in these countries, lack of resources to implement community health programs, or both. Nevertheless, the representation of countries with younger populations and less developed economies (including Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Indonesia, Mexico, and Taiwan) is an indicator of the seriousness with which population aging is treated globally. Population pyramids in these countries are heavily skewed towards younger age categories, in contrast to countries representing the global North, but also are indicative of a shift towards falling birth rates, predicting accelerated future population aging[54]. Thus, it is consistent with the predictions of the population transition model that interest in programs addressing aging-related concerns is growing in countries where these conditions prevail.

The scope and nature of the community health programs evaluated is extremely variable, ranging from local health screening initiatives to national programs establishing elder-care focused health centers. While some disparities exist between developed and developing, it is noteworthy that large scale and relatively resource intensive programs were evaluated in Taiwan and Indonesia, which are both characterized as developing economies by the United Nations [55]. Some cultural differences are also evident in the design of programs for the care of older adults. For example, Japanese community health responses appear to place emphasis on strategies such as promoting family caregiving [43] and encouraging other community members to act as informal screeners identifying older adults with potential health problems [56], perhaps reflecting the nation’s relatively collectivistic cultural orientation. By contrast, approaches in Western nations such as the United States [24, 25], Canada [57], and Australia [42] appear to be more focused on providing support to allow older adults to continue living alone, perhaps reflective of their relatively individualistic cultural orientation.

Beyond the nature of the health interventions themselves, the other major issue raised in this review is the extent to which systematic program evaluation methodologies have been applied to these programs. It is evident that the number of evaluation studies identified for this review is likely to be small in relation to the number of programs that are likely to exist throughout the world. Because the primary audience for these evaluations is likely to be localized to the places where the corresponding programs are implemented, it is likely that at least some of this disparity can be accounted for by publication of evaluations in languages other than English (which fall outside of the inclusion criteria for this review). However, it is also likely that many programs either do not undergo formal evaluation or are evaluated internally without submission to a peer-reviewed publication. Both of these possibilities raise potential problems, because it makes it difficult to judge the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of these measures.

The evaluation methodologies used were highly varied, and it is important to acknowledge the ways in which the nature of the evaluation may impact judgements about program efficacy. For example, a program may have high participant satisfaction but fail to reduce medical service use. Most of the studies reviewed included evaluation of only a single program outcome or dimension. Because the evaluation methodologies applied were so highly varied, it is important to use caution when attempting to draw comparisons between programs in terms of efficacy. Broadly speaking, it appears that most of the evaluations were generally positive and that programs requiring a greater investment of resources tended to be the most successful. For example, programs bringing multiple types of care and/or other services into a single center [18–21, 26, 37, 50] appeared to be evaluated more positively on the whole than programs that focused on solely on case management to coordinate care between disconnected providers [21, 40, 42, 58–60]. This observation was also supported by one of the few studies to contrast evaluations of alternative programs, finding that participants in the PACE program had better outcomes than participants in another, less intensive, US federal program providing only coordination of care [21]. Narrowly-targeted interventions aimed at specific risks such as fall prevention [48–51] and suicide prevention [53] also appeared to have positive impacts. There was less evidence in support of educational programs in terms of impacting health outcomes.

Funding was a common barrier to program success cited in a wide variety of contexts. Evaluators as far removed as the United States [44], Italy [61], and Indonesia [62] all noted that a failure to fully fund specific programs for older adults prevented them from being fully implemented on the national level, and led to geographical disparities in program access. Others noted that uncertain availability of funding to continue a project beyond its pilot period put program sustainability in jeopardy [51]. Barriers to success noted in other studies included lack of public knowledge about program availability [17] and lack of awareness of aging issues among the older adult population [63].

India’s National Programme for the Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE) was not evaluated in any of the studies that met the criteria for inclusion in this review. The NPHCE is an ambitious public and community health program, which ultimately envisions the establishment of programs ranging from the local to the regional level, with diverse specific aims ranging from health education and case management to provision of geriatric facilities [15]. The legislative mandate for this program was established in 1999, but has seen only gradual implementation, as a result of budgetary constraints and other barriers [64]. Based on the experiences of programs initiated in other countries reviewed here, this would seem to be a promising set of approaches, although long-term evaluation will be necessary to establish its impact. For example, the NPHCE implementation plan shares similarities with the PACE [18] and HAN [65] programs in the United States, and the IHSP-Elderly program in Indonesia [37], which have been evaluated positively within the literature covered in this review.

These results can be construed as being consistent with the predictions of the population transition model. In particular, whereas the earlier literature is dominated by programs representative of the global North, there is greater evidence of interest in community health programs serving older adult populations in the global South in more recent years. This is likely to be reflective of nascent trends towards population aging in these contexts. As the global population continues to age, it is likely that these trends will continue and will expand further in regions where population aging has not yet begun to be in evidence. Consequently, it is especially important to learn from the programs currently implemented in these regionsin order toinform successful design in the future. Useful insights for gerontological practice may include the observations that the most effective programs appeared to be those that were either narrowly targeted at interventions in specific behavioral domains (e.g., fall prevention) or those that involved resource-intensive coordination of care across medical service domains. These may be areas of particular interest in terms of program development, in comparison with broader health education and case management programs, which tended to have more ambivalent evaluations.

Limitations of this study include the exclusion of sources not published in English and those published in sources other than peer-reviewed journals. This creates potential geographic limitations, as well as excluding evaluations that may have been disseminated internally within an organization, or externally in a report or other format not covered here. Additionally, it is not possible to account for the extent of publication bias. Researchers may be less likely to seek to publish negative or inconclusive evaluation results, particularly when they are involved directly in the design and/or implementation of the program in question. Finally, promising novel approaches such as voluntary banking systems in which younger adults “deposit” volunteer time providing services for older adults that they can “withdraw” were not evaluated in studies that qualified for inclusion in this review, but nevertheless may be valuable to consider in future research.

Nevertheless, this review highlights some important facets of the literature regarding community health programs aimed at older adults and their evaluation. First, programs outside of North America, Europe, and Japan are dramatically under-represented in the evaluation literature; more research outside of these contexts is called for. Second, many published evaluation projects in this area rely on a single methodology or a single outcome; the literature would be strengthened by research employing multiple methods and a broader set of outcomes when conducting this type of evaluation research. As the global population continues to age at a rapid pace, there will be an increasing demand for information about what approaches are most effective for enhancing care of older adults as well as for reducing the economic burden of providing that care. The literature reviewed in this paper provides substantive evidence in favor of some specific approaches, although much work remains to delineate the most effective approaches, particularly in under-represented global populations.

Conclusion

Community health programs have the potential to address some of the challenges associated with population aging, as supported by the findings of evaluations conducted in many different national contexts and summarized in this review. It is important to include program evaluation as a component of future community and public health interventions aimed at aging populations to better understand how to improve these programs and thereby help meet these needs as they evolve throughout the globe.

Author Contributions

AC and HT conceptualized the review, drafted search terms. AC conducted the literature search and framed the systematic review results, and contributed to manuscript writing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights. New York: United Nations (2019).

2. Li, J, Han, X, Zhang, X, and Wang, S. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Global Population Ageing from 1960 to 2017. BMC Public Health (2019) 19:127. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6465-2

3. Deaton, C, FroelicherESivaraja,, , Wu, LH, Ho, C, Shishani, K, and Jaarsma, T. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs (2011) 10:S5–13. doi:10.1016/S1474-5151(11)00111-3

4. Pilleron, S, Sarfati, D, Janssen-Heijnen, M, Vignat, J, Ferlay, J, Bray, F, et al. Global Cancer Incidence in Older Adults, 2012 and 2035: A Population-Based Study. Int J Cancer (2019) 144:49–58. doi:10.1002/ijc.31664

5. Bommer, C, Sagalova, V, Heesemann, E, Manne-Goehler, J, Atun, R, Bärnighausen, T, et al. Global Economic Burden of Diabetes in Adults: Projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care (2018) 41:963–70. doi:10.2337/dc17-1962

6. Brayne, C, and Miller, B. Dementia and Aging Populations—A Global Priority for Contextualized Research and Health Policy. PLOS Med (2017) 14:e1002275. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002275

7. Bloom, DE, Chatterji, S, Kowal, P, Lloyd-Sherlock, P, McKee, M, Rechel, B, et al. Macroeconomic Implications of Population Ageing and Selected Policy Responses. Lancet (2015) 385:649–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61464-1

8. Omram, AR. The Epidemiologic Transition: a Theory of the Epidemiology of Population Change. Bull World Health Organ (2001) 79:161–70.

9. Bongaarts, J. Human Population Growth and the Demographic Transition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci (2009) 364:2985–90. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0137

10. Scherbov, S, Lutz, W, and Sanderson, WC. The Uncertain Timing of Reaching 8 Billion, Peak World Population, and Other Demographic Milestones. Popul Dev Rev (2011) 37:571–8. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00435.x

11. Castro Torres, AF, Batyra, E, and Myrskylä, M. Income Inequality and Increasing Dispersion of the Transition to First Birth in the Global South. Popul Dev Rev (2022) 48:189–215. doi:10.1111/padr.12451

12.United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019. New York: Vol STESASE A424 Dep Econ Soc AffPopulDiv (2019).

13. Lowell, BL, and Findlay, A. Migration of Highly Skilled Persons from Developing Countries: Impact and Policy Responses. Int Migr Pap (2001) 44:1–45.

14. Powell, JL, and Taylor, P. The Global South: The Case of Populational Aging in Africa and Asia. World Sci News (2015) 12:44–54.

15. Verma, R, and Khanna, P. National Program of Health-Care for the Elderly in India: a hope for Healthy Ageing. Int J Prev Med (2013) 4:1103–7.

16. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Med (2009) 6:e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

17. Ackermann, RT, Williams, B, Nguyen, HQ, Berke, EM, Maciejewski, ML, and LoGerfo, JP. Healthcare Cost Differences with Participation in a Community-Based Group Physical Activity Benefit for Medicare Managed Care Health Plan Members. J Am Geriatr Soc (2008) 56:1459–65. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01804.x

18. Agarwal, G, McDonough, B, Angeles, R, Pirrie, M, Marzanek, F, McLeod, B, et al. Rationale and Methods of a Multicentrerandomised Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of a Community Health Assessment Programme with Emergency Medical Services (CHAP-EMS) Implemented on Residents Aged 55 Years and Older in Subsidised Seniors’ Housing Buildings in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open (2015) 5:e008110. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008110

19. Allen, K, Hazelett, S, Martin, M, and Jensen, C. An Innovation Center Model to Transform Health Systems to Improve Care of Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc (2020) 68:15–22. doi:10.1111/jgs.16235

20. An, R. Association of Home-Delivered Meals on Daily Energy and Nutrient Intakes: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr (2015) 34:263–72. doi:10.1080/21551197.2015.1031604

21. Bartels, SJ, Gill, L, and Naslund, JA. The Affordable Care Act, Accountable Care Organizations, and Mental Health Care for Older Adults: Implications and Opportunities. Harv Rev Psychiatry (2015) 23:304–19. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000086

22. Beeber, AS. Luck and Happenstance: How Older Adults Enroll in a Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Prof Case Manag (2008) 13:277–83. doi:10.1097/01.PCAMA.0000336691.00694.65

23. Belza, B, Altpeter, M, Smith, ML, and Ory, MG. The Healthy Aging Research Network: Modeling Collaboration for Community Impact. Am J Prev Med (2017) 52:S228–S232. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.035

24. Bernabei, R, Landi, F, and Zuccalà, G. Health Care for Older Persons in Italy. Aging Clin Exp Res (2002) 14:247–51. doi:10.1007/BF03324446

25. Chambers, LW, Kaczorowski, J, Dolovich, L, Karwalajtys, T, Hall, HL, McDonough, B, et al. A Community-Based Program for Cardiovascular Health Awareness. Can J Public Health (2005) 96:294–8. doi:10.1007/BF03405169

26. Cheadle, A, Egger, R, LoGerfo, JP, Schwartz, S, and Harris, JR. Promoting Sustainable Community Change in Support of Older Adult Physical Activity: Evaluation Findings from the Southeast Seattle Senior Physical Activity Network (SESPAN). J Urban Health (2010) 87:67–75. doi:10.1007/s11524-009-9414-z

27. Chiang, Y-H, and Hsu, H-C. Health Outcomes Associated with Participating in Community Care Centres for Older People in Taiwan. Health Soc Care Community (2019) 27:337–47. doi:10.1111/hsc.12651

28. de Vlaming, R, Haveman-Nies, A, Van’t Veer, P, and de Groot, LC. Evaluation Design for a Complex Intervention Program Targeting Loneliness in Non-institutionalized Elderly Dutch People. BMC Public Health (2010) 10:552. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-552

29. Duke, C. The Frail Elderly Community-Based Case Management Project. Geriatr Nurs (2005) 26:122–7. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.03.003

30. Forti, EM, and Koerber, M. An Outreach Intervention for Older Rural African Americans. J Rural Health (2002) 18:407–15. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00905.x

31. Goeree, R, von Keyserlingk, C, Burke, N, He, J, Kaczorowski, J, Chambers, L, et al. Economic Appraisal of a Community-wide Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program. Value Health (2013) 16:39–45. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2012.09.002

32. Gyurmey, T, and Kwiatkowski, J. Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): Integrating Health and Social Care since 1973. R Med J (2013) 102:30–2.

33. Honigh-de Vlaming, R, Haveman-Nies, A, Heinrich, J, van’t Veer, P, and de Groot, LCPGM. Effect Evaluation of a Two-Year Complex Intervention to Reduce Loneliness in Non-institutionalised Elderly Dutch People. BMC Public Health (2013) 13:984. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-984

34. Imamura, E. Amy’s Chat Room: Health Promotion Programmes for Community Dwelling Elderly Adults. Int J Nurs Pract (2002) 8:61–4. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172x.2002.00349.x

35. Ippoliti, R, Allievi, I, Falavigna, G, Giuliano, P, Montani, F, Obbia, P, et al. The Sustainability of a Community Nurses Programme Aimed at Supporting Active Ageing in Mountain Areas. Int J Health Plann Manage (2018) 33:e1100–11. doi:10.1002/hpm.2591

36. Kadar, KS, McKenna, L, and Francis, K. Scoping the Context of Programs and Services for Maintaining Wellness of Older People in Rural Areas of Indonesia. Int Nurs Rev (2014) 61:310–7. doi:10.1111/inr.12105

37. Kane, RL, Homyak, P, Bershadsky, B, Flood, S, and Zhang, H. Patterns of Utilization for the Minnesota Senior Health Options Program. J Am Geriatr Soc (2004) 52:2039–44. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52558.x

38. Kronborg, C, Vass, M, Lauridsen, J, and Avlund, K. Cost Effectiveness of Preventive home Visits to the Elderly: Economic Evaluation Alongside Randomized Controlled Study. Eur J Health Econ (2006) 7:238–46. doi:10.1007/s10198-006-0361-2

39. Larsen, ER, Mosekilde, L, and Foldspang, A. Determinants of Acceptance of a Community-Based Program for the Prevention of Falls and Fractures Among the Elderly. Prev Med (2001) 33:115–9. doi:10.1016/S0091-7435(01)80007-4

40. Lawson, B, Sampalli, T, Warner, G, Burge, F, Moorhouse, P, Gibson, R, et al. Improving Care for the Frail in Nova Scotia: An Implementation Evaluation of a Frailty Portal in Primary Care Practice. Int J Health Pol Manag (2019) 8:112–23. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2018.102

41. Lawson, B, Sampalli, T, Wood, S, Warner, G, Moorhouse, P, Gibson, R, et al. Evaluating the Implementation and Feasibility of a Web-Based Tool to Support Timely Identification and Care for the Frail Population in Primary Healthcare Settings. Int J Health Pol Manag (2017) 6:377–82. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2017.32

42. Li, X, Li, T, Chen, J, Xie, Y, An, X, Lv, Y, et al. A WeChat-Based Self-Management Intervention for Community Middle-Aged and Elderly Adults with Hypertension in Guangzhou, China: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16:E4058. doi:10.3390/ijerph16214058

43. Liang, C-C, Change, Q-X, Hung, Y-C, Chen, C-C, Lin, C-H, Wei, Y-C, et al. Effects of a Community Care Station Program with Structured Exercise Intervention on Physical Performance and Balance in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective 2-Year Observational Study. J Aging Phys Act (2017) 25:596–603. doi:10.1123/japa.2015-0326

44. Lindqvist, K, Timpka, T, and Schelp, L. Evaluation of an Inter-organizational Prevention Program against Injuries Among the Elderly in a WHO Safe Community. Public Health (2001) 115:308–16. doi:10.1038/sj.ph.1900786

45. Liu, M, Zhang, X, Xiao, J, Ge, F, Tang, S, and Belza, B. Community Readiness Assessment for Disseminating Evidence-Based Physical Activity Programs to Older Adults in Changsha, China: a Case for Enhance®Fitness. Glob Health Promot (2020) 27:59–67. doi:10.1177/1757975918785144

46. Lowe, M, and Coffey, P. Effect of an Ageing Population on Services for the Elderly in the Northern Territory. Aust Health Rev (2019) 43:71–7. doi:10.1071/AH17068

47. Luzinski, CH, Stockbridge, E, Craighead, J, Bayliss, D, Schmidt, M, and Seideman, J. The Community Case Management Program: for 12 Years, Caring at its Best. Geriatr Nurs (2008) 29:207–15. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.01.010

48. Martínez-Maldonado, Mde la L, Chapela, C, and Mendoza-Núñez, VM. Training of Mexican Elders as Health Promoters: a Qualitative Study. Health Promot Int (2019) 34:735–50. doi:10.1093/heapro/day026

49. Matsudo, SM, Matsudo, VR, Araujo, TL, Andrade, DR, Andrade, EL, de Oliveira, LC, et al. The Agita São Paulo Program as a Model for Using Physical Activity to Promote Health. Rev Panamsalud Publica Pan Am J Public Health (2003) 14:265–72. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892003000900007

50. Matsudo, V, Matsudo, S, Andrade, D, Araujo, T, Andrade, E, de Oliveira, LC, et al. Promotion of Physical Activity in a Developing Country: the Agita São Paulo Experience. Public Health Nutr (2002) 5:253–61. doi:10.1079/phn2001301

51. McCarrell, J. PACE: An Interdisciplinary Community-Based Practice Opportunity for Pharmacists. Sr Care Pharm (2019) 34:439–43. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2019.439

52. Mukamel, DB, Gold, HT, and Bennett, NM. Cost Utility of Public Clinics to Increase Pneumococcal Vaccines in the Elderly. Am J Prev Med (2001) 21:29–34. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00312-9

53. Murashima, S, and Asahara, K. The Effectiveness of the Around-The-Clock in-home Care System: Did it Prevent the Institutionalization of Frail Elderly? Public Health Nurs (2003) 20:13–24. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20103.x

54. Nakamura, Y, Matsumoto, H, Yamamoto-Mitani, N, Suzuki, M, and Igarashi, A. Impact of Support Agreement between Municipalities and Convenience Store Chain Companies on Store Staff’s Support Activities for Older Adults. Health Policy (2018) 122:1377–83. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.09.015

55. Nakanishi, M, Yamasaki, S, and Nishida, A. In-hospital Dementia-Related Deaths Following Implementation of the National Dementia Plan: Observational Study of National Death Certificates from 1996 to 2016. BMJ Open (2018) 8:e023172. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023172

56. Olivares-Tirado, P, Tamiya, N, and Kashiwagi, M. Effect of in-home and Community-Based Services on the Functional Status of Elderly in the Long-Term Care Insurance System in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res (2012) 12:239. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-239

57. Otaka, Y, Morita, M, Mimura, T, Uzawa, M, and Liu, M. Establishment of an Appropriate Fall Prevention Program: A Community-Based Study. Geriatr Gerontol Int (2017) 17:1081–9. doi:10.1111/ggi.12831

58. Oyama, H, Koida, J, Sakashita, T, and Kudo, K. Community-based Prevention for Suicide in Elderly by Depression Screening and Follow-Up. Community Ment Health J (2004) 40:249–63. doi:10.1023/b:comh.0000026998.29212.17

59. Pacala, JT, Kane, RL, Atherly, AJ, and Smith, MA. Using Structured Implicit Review to Assess Quality of Care in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). J Am Geriatr Soc (2000) 48:903–10. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06886.x

60. Ploeg, J, Hayward, L, Woodward, C, and Johnston, R. A Case Study of a Canadian Homelessness Intervention Programme for Elderly People. Health Soc Care Community (2008) 16:593–605. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00783.x

61. Rahmawati, R, and Bajorek, B. A Community Health Worker-Based Program for Elderly People with Hypertension in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis (2015) 12:E175. doi:10.5888/pcd12.140530

62. Rana, AKMM, Wahlin, A, Lundborg, CS, and Kabir, ZN. Impact of Health Education on Health-Related Quality of Life Among Elderly Persons: Results from a Community-Based Intervention Study in Rural Bangladesh. Health Promot Int (2009) 24:36–45. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan042

63. Sakayori, T, Maki, Y, Ohkubo, M, Ishida, R, Hirata, S, and Ishii, T. Longitudinal Evaluation of Community Support Project to Improve Oral Function in Japanese Elderly. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll (2016) 57:75–82. doi:10.2209/tdcpublication.2015-0035

64. Segelman, M, Cai, X, van Reenen, C, and Temkin-Greener, H. Transitioning from Community-Based to Institutional Long-Term Care: Comparing 1915(c) Waiver and PACE Enrollees. Gerontologist (2017) 57:300–8. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv106

65. Shinkai, S, Yoshida, H, Taniguchi, Y, Murayama, H, Nishi, M, Amano, H, et al. Public Health Approach to Preventing Frailty in the Community and its Effect on Healthy Aging in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int (2016) 16(1):87–97. doi:10.1111/ggi.12726

66. Smith, ML, Durrett, NK, Schneider, EC, Byers, IN, Shubert, TE, Wilson, AD, et al. Examination of Sustainability Indicators for Fall Prevention Strategies in Three States. Eval Program Plann (2018) 68:194–201. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2018.02.001

67. Tomioka, M, Sugihara, N, and Braun, KL. Replicating the EnhanceFitness Physical Activity Program in Hawai`i’s Multicultural Population, 2007-2010. Prev Chronic Dis (2012) 9:E74. doi:10.5888/pcd9.110155

68. Vass, M, Avlund, K, Lauridsen, J, and Hendriksen, C. Feasible Model for Prevention of Functional Decline in Older People: Municipality-Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc (2005) 53:563–8. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53201.x

69. Vouri, SM, Crist, SM, Sutcliffe, S, and Austin, S. Changes in Mood in New Enrollees at a Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly. Consult Pharm (2015) 30:463–71. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2015.463

70. Wang, C-S, Wang, S-T, and Chou, P. Efficacy and Cost-Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination of the Elderly in a Densely Populated and Unvaccinated Community. Vaccine (2002) 20:2494–9. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00181-0

71. Wieland, D, Boland, R, Baskins, J, and Kinosian, B. Five-year Survival in a Program of All-Inclusive Care for Elderly Compared with Alternative Institutional and home- and Community-Based Care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2010) 65:721–6. doi:10.1093/gerona/glq040

72. Wildman, JM, Valtorta, N, Moffatt, S, and Hanratty, B. “What Works Here Doesn’t Work There”: The Significance of Local Context for a Sustainable and Replicable Asset-Based Community Intervention Aimed at Promoting Social Interaction in Later Life. Health Soc Care Community (2019) 27:1102–10. doi:10.1111/hsc.12735

73. Wright, L, Vance, L, Sudduth, C, and Epps, JB. The Impact of a Home-Delivered Meal Program on Nutritional Risk, Dietary Intake, Food Security, Loneliness, and Social Well-Being. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr (2015) 34:218–27. doi:10.1080/21551197.2015.1022681

74. Yasunaga, M, Murayama, Y, Takahashi, T, Ohba, H, Suzuki, H, Nonaka, K, et al. Multiple Impacts of an Intergenerational Program in Japan: Evidence from the Research on Productivity through Intergenerational Sympathy Project. Geriatr Gerontol Int (2016) 16(1):98–109. doi:10.1111/ggi.12770

75.Population Pyramid. Population Pyramids of the World from 1950 to 2100. In: PopulationPyramid.net. Visual Capitalist (2022). Available at: https://www.populationpyramid.net/world/2019/ (Accessed April 21, 2022).

76.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Economic Situation and Prospects. New York: United Nations (2021).

Keywords: older adults, global health, program evaluation, aging, community health

Citation: Chandrashekhar A and Thakur HP (2022) Efficacy of Government-Sponsored Community Health Programs for Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Published Evaluation Studies. Public Health Rev 43:1604473. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604473

Received: 18 September 2021; Accepted: 02 September 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

Musa Abubakar Kana, Federal University Lafia, NigeriaCopyright © 2022 Chandrashekhar and Thakur. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Arun Chandrashekhar, Y2hhbmRyYXNoZWtoYXIuc0Bwcm90b24ubWU=

Arun Chandrashekhar

Arun Chandrashekhar Harshad P. Thakur

Harshad P. Thakur