- 1Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

- 2Department of Sociology, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

- 32gether 4 SRHR, United Nations Population Fund, Johannesburg, South Africa

Objectives: There is a need to hone reproductive health (RH) services for women who sell sex (WSS). The aim of this review was to collate findings on non-barrier contraception, pregnancies, and abortion amongst WSS in Eastern and Southern African (ESA).

Methods: A scoping review methodology was employed. Inclusion criteria were: 1) empirical papers from 2) ESA, 3) published since 2010, and 4) addressing WSS in relation to 5) the identified RH issues.

Results: Reports of rates of non-barrier contraceptive usage varied from 15% to 76%, of unintended pregnancy from 24% to 91%, and of abortion from 11% to 48%. Cross-cutting factors were alcohol use, violence, health systems problems, and socio-economic issues. Pregnancy desire was associated with having a non-paying partner. Barriers to accessing, and delaying, antenatal care were reported as common. Targeted programmes were reported as promoting RH amongst WSS.

Conclusion: Programmes should be contextually relevant, based on local patterns, individual, interpersonal and systemic barriers. Targeted approaches should be implemented in conjunction with improvement of public health services. Linked HIV and RH services, and community empowerment approaches are recommended.

Introduction

Women who sell sex (WSS) receive money or goods in exchange for sexual services, either regularly or occasionally. Sex work varies in nature from formal and organised to informal. It constitutes consensual transactional sex between adults [1]. Given the nature of the work, it is unsurprising that WSS have special reproductive health (RH) needs [2]. For example, women who sell sex in sub-Saharan Africa are at higher risk of maternal morbidity and mortality than the general population because of their high rates of HIV, unintended pregnancies, and abortions [3].

The importance, thus, of honing sexual and reproductive health services to meet the needs of women who sell sex (WSS) is being increasingly recognised [4]. In 2014, Dhana and colleagues [5] published a review describing clinical and non-clinical facility-based sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for WSS in Africa. The review revealed a narrow focus on HIV prevention, counselling and testing, and STIs; in addition, most interventions were localised and small-scale, operated with little coordination nationally or regionally, and had scanty government support. Broader SRH needs such as contraception services, antenatal care and abortion were generally ignored.

Women who sell sex in Africa generally experience limited economic options, many dependents, marital disruption, and low levels of education. Their work may involve violence, criminalisation, high mobility and hazardous substance use [6]. These factors, together with the occupational contexts of their work, have highlighted their vulnerability to HIV, about which a reasonable amount of research has been conducted [7]. Less, however, is known about WSS in relation to their reproductive health needs and desires. The aims of the review are to identify the following issues in relation to reproductive health amongst WSS in Eastern and Southern Africa: non-barrier contraceptive usage prevalence, and associated factors; unintended pregnancy prevalence and associated factors, pregnancy desires, antenatal care; abortion prevalence and associated factors; access and barriers to services; and positive service delivery programmes.

We take a reproductive health rights approach in this paper. The World Health Organization’s constitution envisages “the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being” [8] (emphasis added). A reproductive health rights approach means that states should ensure access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care of appropriate quality. Such an approach is essential in designing broad-based programmes to address the reproductive health needs of marginalised communities, such as WSS.

Methods

Scope

The scoping review methodology employed by Arksey and O’Malley [9] was used in this project. This consists of the following stages: 1) identifying the research question; 2) identifying relevant studies; 3) study selection; 4) charting the data; and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. This method is designed to systematically map the subject field.

Publication Selection and Data Extraction

The following electronic databases were searched in April 2021: Academic Search Premier; Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition; Medline; PsyArticles; PsyINFO; SocIndex; Sabinet; Web of Science; PubMed; and Google scholar. The keyword search for studies was: Female sex workers1 OR sex workers AND contraception OR family planning OR reproduct* OR pregnan* OR antenatal care OR abortion AND [list of countries] OR Eastern Africa OR Southern Africa. The search was restricted to the last 10 years to ensure that the information is current. No language restriction was placed on the search, in case there were relevant papers in another language (most likely French or Portuguese). The search, however, only surfaced papers written in English.

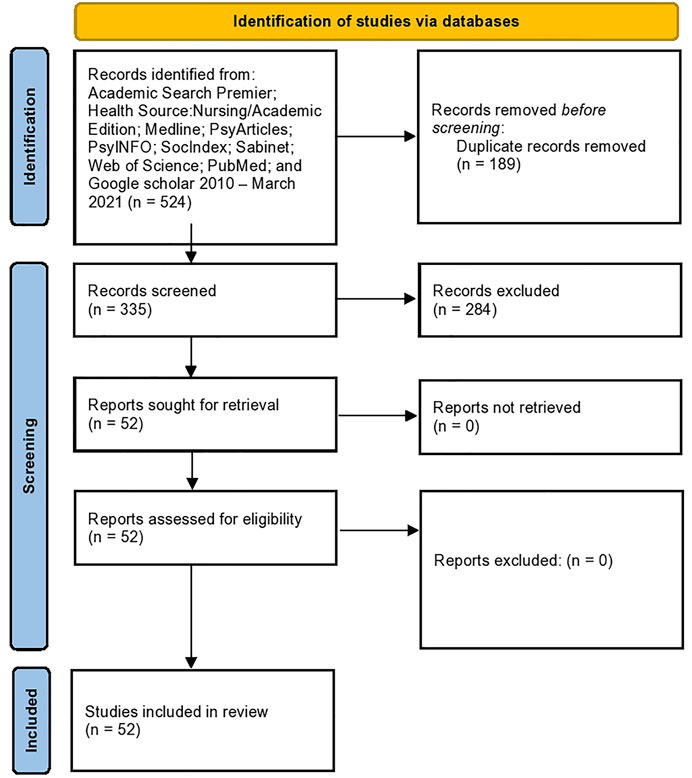

The initial search produced 524 papers. After duplicates were removed, the two authors went through the papers independently, determining whether the identified studies were relevant to the research aims. Inclusion criteria were that the papers should: 1) be empirical papers; 2) specifically address WSS in relation to 3) the identified RH issues and 4) be conducted in ESA countries. Each author’s assessments were compared. Differences were resolved through discussion. The papers were quality checked through use of the Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [5]. No studies were discarded following this assessment. No further papers were found on checking the reference list of downloaded papers. The result was 53 papers. The process is displayed in an adapted PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. PRISMA diagram, Women Who Sell Sex in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Scoping Review of Non-Barrier Contraception, Pregnancy and Abortion (scoping review, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010-2020).

The studies were charted as follows. First, eligible studies were summarized, including the following information for each publication: author(s); year of publication; study location; programme researched (where relevant); study populations; aims of the study; data collection method; important results; study recommendations. Second, attention was paid to the distribution of the studies in relation to country and SRH issue (non-barrier contraception, pregnancy, antenatal care, abortion). Third, the literature and information on programmes was organized thematically using the research aims provided above as a template for analysis.

Results

Fourteen of the studies were conducted in Kenya [10–23], eight in South Africa [13, 14, 24–29], eight in Uganda [30–37], six in Mozambique [13, 14, 38–40], five in Tanzania [41–45], three in Eswatini [46–48] and in Malawi [49–51], two in Ethiopia [52, 53], in Zambia [54, 55], and in Zimbabwe [56, 57] and one each in Democratic Republic of Congo [58], Lesotho [59], Rwanda [60], and online (Australia, Brazil, El Salvador, France, Kenya, Malawi, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Tanzania, the United States of America, and Zimbabwe) [56]. Thus, knowledge production concerning WSS in relation to non-barrier contraception, pregnancy and abortion is dominated by studies conducted in Kenya. There are many countries in which no published studies have been conducted. Non-barrier contraception usage was the most researched topic. In contrast, there were few studies concentrating specifically on abortion.

In the following, we outline findings in relation to non-barrier contraception, pregnancies, abortion, needs and barriers in relation to health services, and promising programme developments.

Non-Barrier Contraception

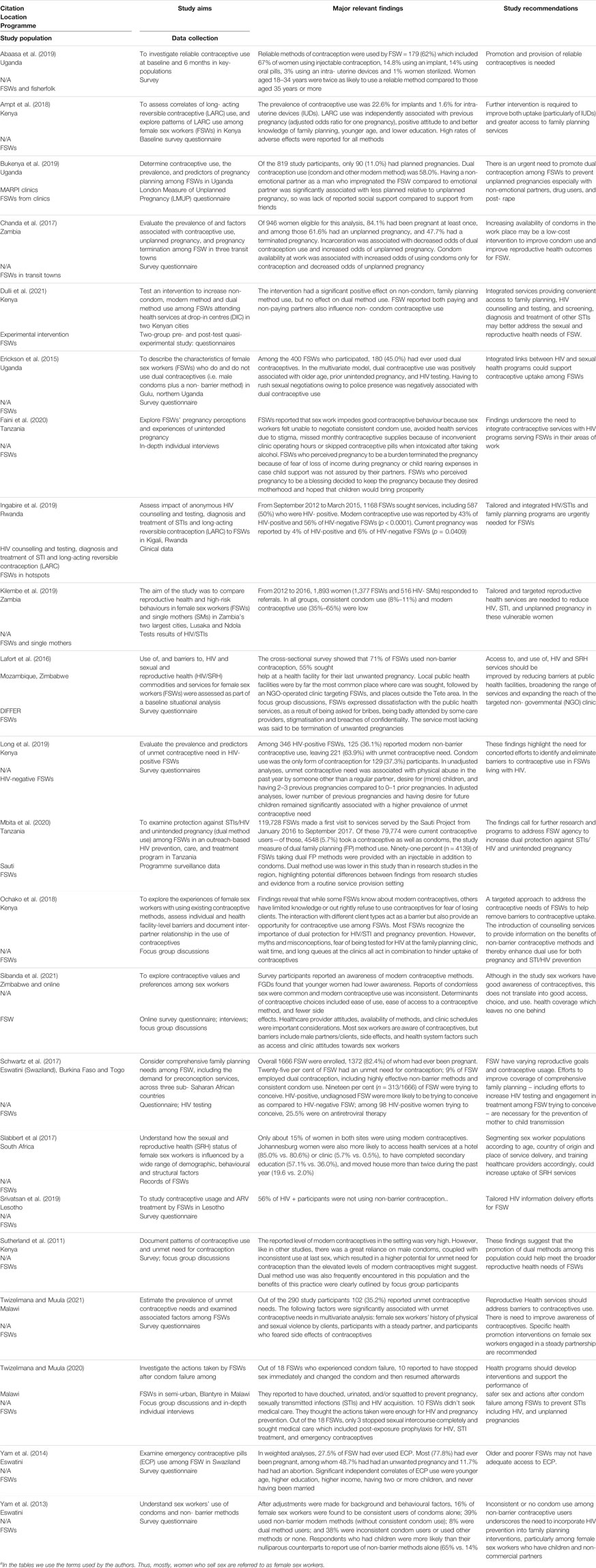

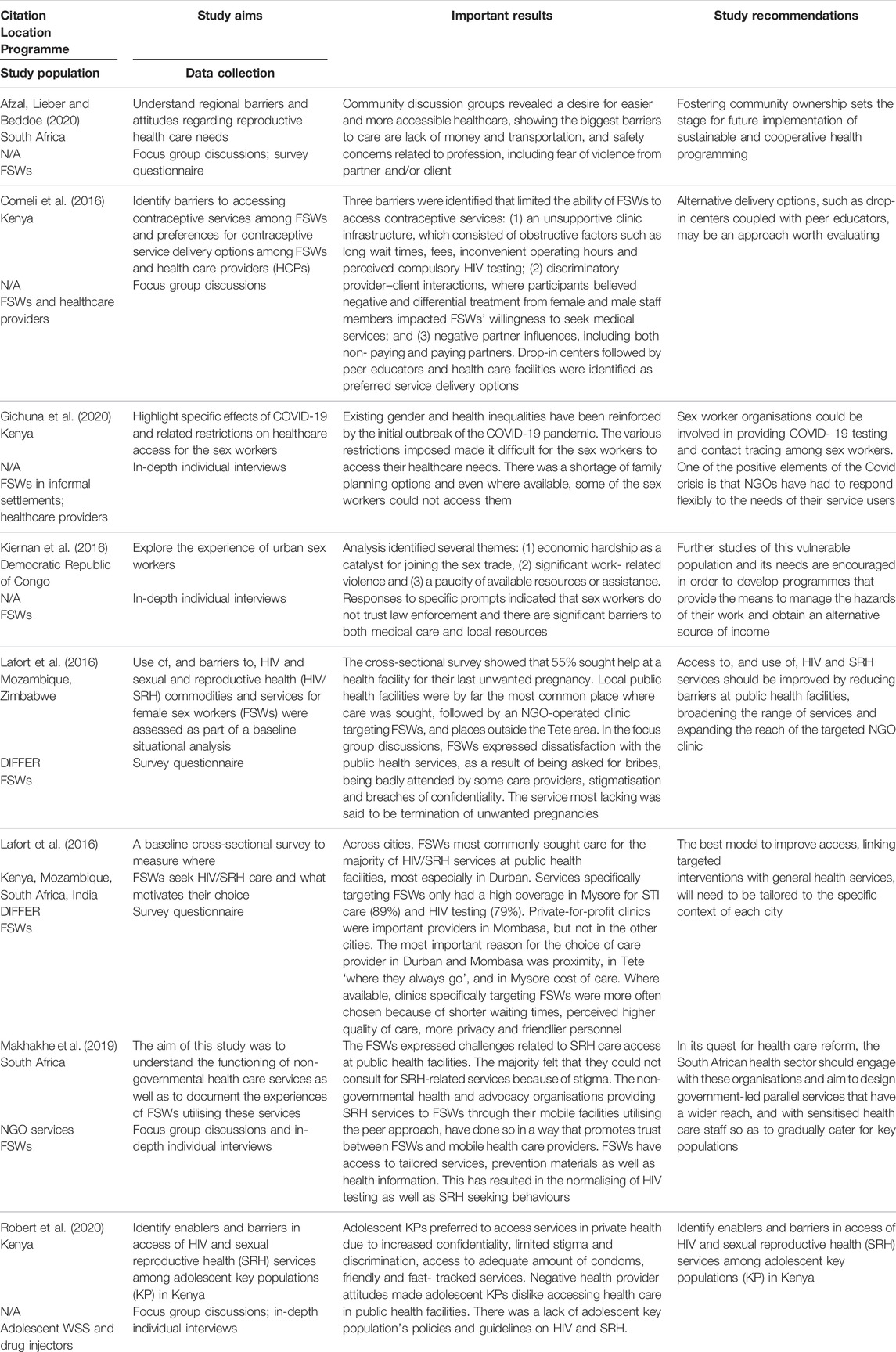

Table 1 provides an overview of the major findings and recommendations of studies that concentrated specifically on non-barrier contraceptive usage.

TABLE 1. aStudies’ findings and recommendations for women who sell sex and non-barrier contraception (Women Who Sell Sex Project, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010–2021).

Reports of the use of non-barrier modern contraception varied considerably across studies. The lowest was 15% in a South African study [24]. The highest was 76.3% in one site in a Kenyan study [10]. The former study accessed records of WSS attending regular services across two cities, while the latter reported on baseline data of a targeted intervention in towns where tourists, migrant workers and military personnel have attracted a high number of WSS. This may account for the differences noted. One study was conducted in the context of a targeted intervention (in Rwanda), and reported usage of 43% by HIV-positive participants and 56% by HIV-negative participants [19]. The rest of studies, using respondent-driven survey data or longitudinal data, reported usage somewhere between 30% and 71%: 36.1% and 30.5% in two Kenyan studies [11, 16]; 39% in a study conducted in Eswatini [13]; between 35% and 41% in a Zambian study [54]; 47.5% in a different site in the above-mentioned Kenyan study [14]; 56% amongst HIV-positive WSS in Lesotho [59];; 66.6% in Zambian study [55]; 71% in a study conducted in Mozambique [38].

A study focussing on long-acting reversible contraception in Kenya found that 22.6% of participants used implants and 1.6% IUDs. Dual contraception usage was reported as low in some studies—5.7% in the context of a targeted programme in Tanzania [41]; 8% in Eswatini (respondent-driven survey) [46]; 9% in Eswatini (combined study with Togo and Burkina Faso—respondent driven survey) [48]. However, others reported higher rates—43.4% in a Malawian study (systematic sampling survey) [49], 58% in a Ugandan study (survey in context of targeted services) [30], 30.7% and 50.5% in two sites in Kenya (baseline for targeted service) [10]; 38% in another Kenyan study (respondent-driven survey) [17]. Only one Eswatini study (respondent-driven survey) focused on emergency contraception: 27.5% of study participants had ever used emergency contraception [47].

Various studies addressed variables associated with non-use of non-barrier contraceptive. Studies did not necessarily use the same variables. We therefore list all found (noting that some may not apply in certain areas, while others may apply but were not included in the study). Variables include: personal factors – fear of side effects [10, 51]. desire for (more) children [11], being nulliparous [46], history of incarceration or arrest [55], intoxication [42], and being older than 35 [31]; interpersonal factors—male partners’ or clients’ disapproval [10], physical or sexual abuse [9, 16], having a steady partner [51]; and systemic issues—poor clinic access [10, 42], negative healthcare provider attitudes [10], and condom availability at work [55]. Use of non-barrier contraception was found in to be associated with ease of access, positive healthcare provider attitudes, conducive clinic schedules, fewer side effects [56], previous pregnancy, positive attitude to and knowledge of family planning, younger age, and lower education [18]. Independent correlates of emergency contraception use were younger age, higher education, higher income, having two or more children, and never having been married [47]. Dual contraception was positively associated in a Ugandan study with older age, prior unintended pregnancy and HIV testing. Rushing sexual negotiations owing to police presence was negatively associated with dual contraception usage [32]. In a qualitative study conducted in Kenya, Ochako and colleagues [19] found that most participants recognised the importance of dual contraception but that there were various barriers to use, including misconceptions (e.g. IUDs falling out), fear of being tested for HIV at family planning clinics, wait times and long queues.

Pregnancy and Antenatal Care

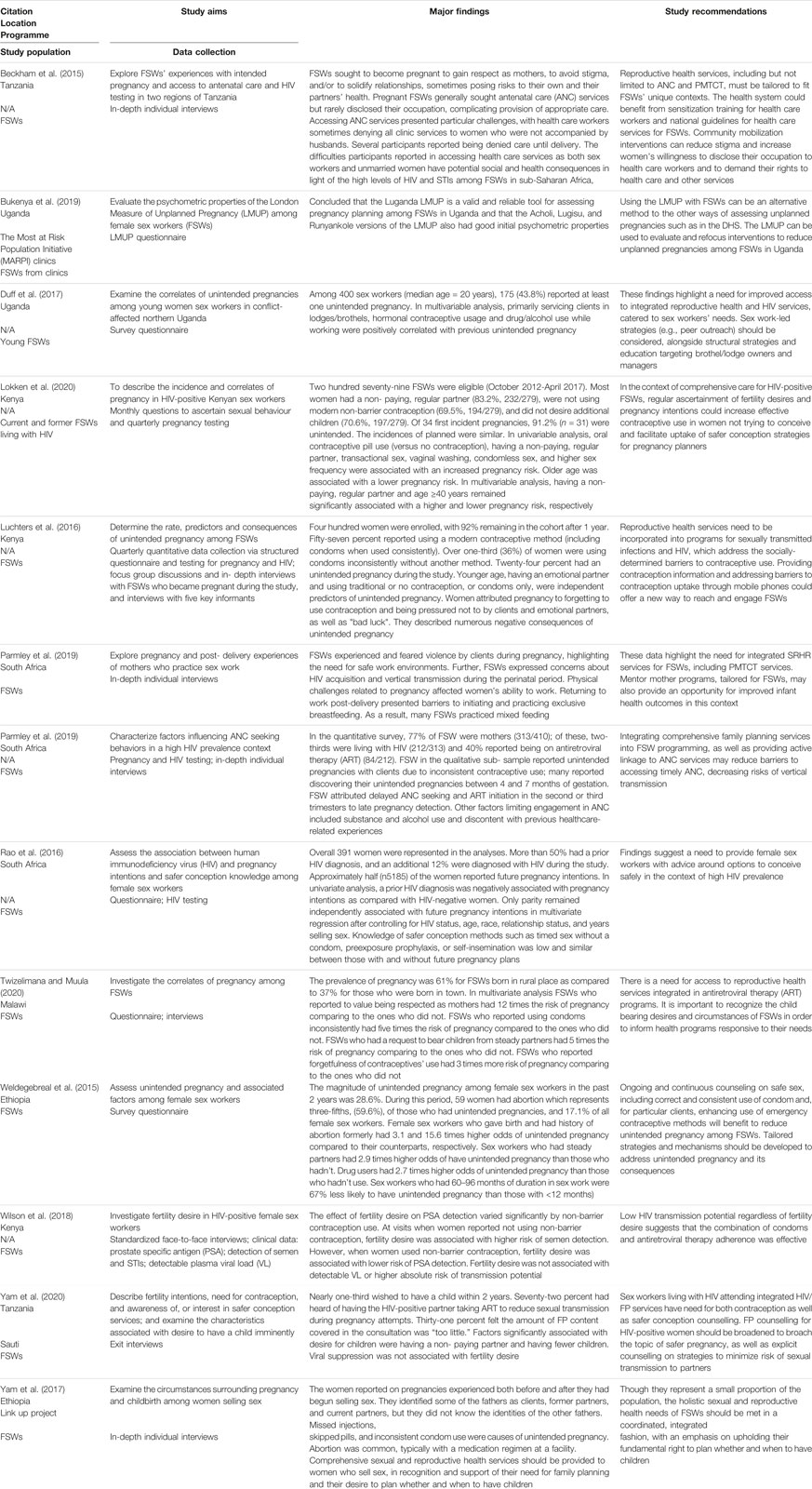

Table 2 outlines the studies’ findings and recommendations in relation to unintended pregnancies, pregnancy desire, and pregnancy care.

TABLE 2. Studies’ findings and recommendations for women who sell sex and pregnancy (Women Who Sell Sex Project, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010–2021).

Yam et al. [53] outline the challenges in meeting the reproductive health needs of pregnant sex workers, these being: “an entrenched societal aversion regarding FSWs [female sex workers] as pregnant women or mothers, the “siloed” nature of HIV and reproductive health programming and financing, and the challenges of balancing FSWs’ disease prevention needs with the childbearing desires” (p. 117).

The question of unintended pregnancies was addressed in a number of studies, with reports of rates varying. For example, the following rates were reported in Kenyan studies:

• Of those with first pregnancies in [16] study, 91.2% were reported as unintended.

• In a Sutherland’s study [17], unintended pregnancies were reported by 52% of participants.

• Luchters et al. [20] found that 24% of their Kenyan participants had an unintended pregnancy during the study conducted over 12 months

In a Zambian survey, Chanda et al. [55] report that of the respondents who had been pregnant, 61.6% had had an unplanned pregnancy. In Northern Uganda, Duff et al. [33] found an unintended pregnancy rate of 43.8%. None of these rates were collected in the context of a study about targeted services.

Factors associated with unintended pregnancies were: primarily servicing clients in lodges or brothels [33]; hormonal contraceptive (injections) usage [33]; drug or alcohol use during work [33, 52]; having four or more living children [34]; non-emotional partner as a man who fathered last pregnancy [34]; having had an abortion [34]; being unmarried [34]; having a steady non-paying partner [52]; and longer duration of sex work [52].

Twizelimana and Muula [50] emphasise the importance of considering the child bearing desires and circumstances of women who sell sex so that health programmes can respond to their needs. Non- paying partner request and being born in a rural area contributed to pregnancy desire for their Malawian participants. This is confirmed in a Tanzanian study [43]. in which just under one-third of participants desired having a child in the next 2 years. Having non-paying partners and fewer children were associated with this desire.

In South African study [25], about half the participants reported future pregnancy intentions. In univariate analysis, HIV diagnosis was negatively associated with pregnancy intentions as compared with HIV-negative women. But in multivariate analysis, only parity remained independently associated with future pregnancy intentions. In a three country study (Eswatini, Burkina Faso and Togo), Schwartz et al. [48] found that HIV-positive, undiagnosed sex workers were more likely to be trying to conceive than HIV-negative sex workers. Wilson et al. [21] noted that fertility desire could increase HIV transmission in HIV-positive sex workers. However, in their Kenyan study, they found that the combination of condoms and antiretroviral therapy adherence was effective in preventing this.

Knowledge of safer conception methods was investigated in two studies. In a South African study [25], 59.3% of women knew of ARV-based methods for safer conception, and 14.3% of non-ARV methods. In Tanzania [43], 90% of participants knew of one safer conception method, with 72% having heard of having the seropositive partner taking ART.

Delayed seeking of antenatal care was found in a South African study [27]. This was attributed to late pregnancy detection, alcohol and substance use, and discontent with previous healthcare-related experiences. Challenges accessing antenatal care were likewise revealed in a Tanzanian study [44]. Healthcare workers reportedly would sometimes deny clinic services to women not accompanied by their husbands. In addition, participants indicated that they rarely disclosed their occupation to healthcare workers, thereby jeopardising receiving appropriate care.

In a qualitative study conducted in Gqerbherha (formerly Port Elizabeth) [26], South Africa, sex workers indicated that they had experienced violence by clients during pregnancy. They expressed concerns about HIV acquisition and vertical transmission of HIV during the perinatal period. Physical challenges during pregnancy affected their ability to work, and work post-partum interfered with exclusive breast- feeding.

Abortion

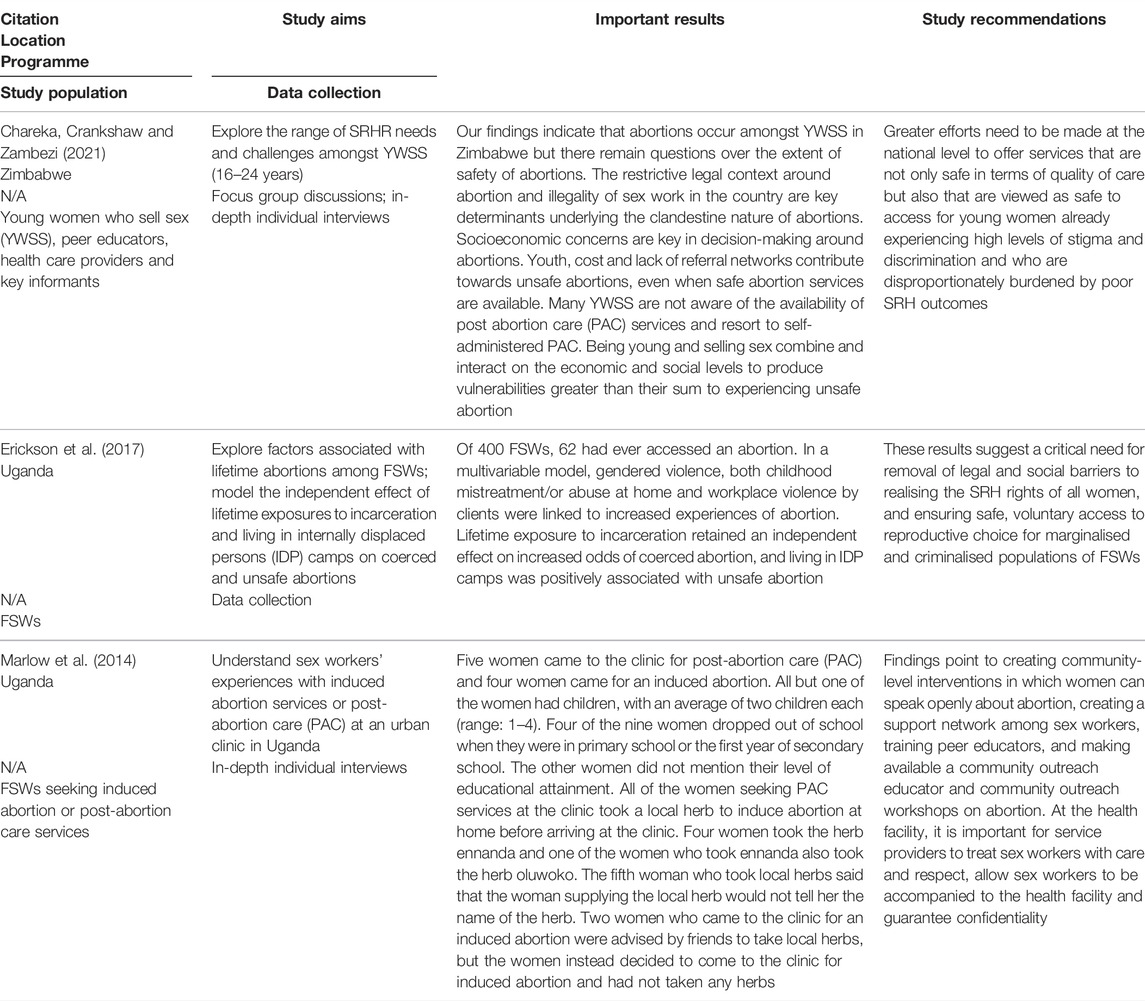

Only three studies in the dataset concentrated specifically on abortion. This is regrettable, given the fact that, as pointed out by Marlow and colleagues [35], sex workers’ need for safe abortion services is greater than that of other women of reproductive age because of their number of sexual contacts, and their increased risk of sexual violence. The major findings and recommendations from these studies are contained in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Studies’ findings and recommendations for women who sell sex and abortion (Women Who Sell Sex Project, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010–2021).

A number of studies do, however, refer to abortion in passing, confirming Marlow et al.’s assertion. A survey of WSS in Eswatini found that 48.7% had had an unwanted pregnancy, and 11.7% had undergone an abortion [47], while in an Ethiopian study [52], 59.6% of participants with an unintended pregnancy had an abortion, or 17.1% of all participants. Chanda et al. [55] report that of the sex workers who had been pregnant at least once in their Zambian survey, 47.7% had terminated an unplanned pregnancy. In a Kenyan study [10], 17.5% and 12.8% of respondents in two sites indicated that they had had an abortion. Participants in Lafort et al.’s [38] study in Mozambique reported that the most lacking service was for the termination of unwanted pregnancies. Sex workers in Tanzania reported terminating their pregnancies because of fear of loss of income during pregnancy or because of child rearing expenses [42].

Reasons for seeking abortions included not knowing the man responsible for the pregnancy, inability to raise an additional child, incest, wanting to continue with education [35], and socioeconomic concerns [57]. Gendered violence, including childhood maltreatment at home and workplace violence by clients were associated in a Ugandan study with abortions.

In a Zimbabwean study [57], youth, cost and lack of referral networks were reported as contributing to unsafe abortions, even when safe abortion services were available. Awareness of post abortion care (PAC) services was low, resulting in women having self-administered PAC. Marlow et al. [35] found in their Ugandan study that women took a local herb to induce abortion. The lower cost of taking herbs often swayed women in their decision. Erickson et al. [36] found that incarceration and living in internally displaced persons camps were associated with coerced and unsafe abortions respectively. 37.

Health Services Needs and Barriers

Table 4 outlines major findings and study recommendations for studies focussing specifically on health services needs and barriers for women who sell sex.

TABLE 4. Studies’ findings and recommendations for women who sell sex and health services (Women Who Sell Sex Project, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010–2021).

A number of barriers to contraceptive services were identified in the studies. These include: long clinic wait times [22]; having to pay medical fees [22, 28]; being asked for bribes [38]; inconvenient clinic operating hours [22, 42]; perceived compulsory HIV testing at clinics [22]; discriminatory provider-client interactions [22]; inadequate care [38, 58]; paucity of available services [58]; stigmatisation [29, 38, 42]; breaches in confidentiality [38]; lack of transport [28]; negative partner influences [22, 28].

Gichuna and colleagues [23] conducted interviews with WSS and healthcare practitioners in Kenya regarding service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, they found that the sex workers struggled to access services, and “to accept the [resultant] harsh reality of carrying unwanted pregnancies” (p. 1430).

Lafort et al. [38] found that 55% of women who sell sex in Tete, Mozambique sought help at a health facility for their last unwanted pregnancy. Public health facilities were the most frequently used, followed by an NGO-operated clinic targeting sex workers. Likewise, in a Kenyan study [12], it was found that young WSS prefer accessing services in private healthcare on the basis of better confidentiality, limited discrimination and stigma, adequate commodities, and fast and friendly services. Drop-in centres and peer educators were identified as preferred service delivery options. Healthcare resources and service coverage in general are key issues in SRH services for WSS. By way of example, Lafort etal [39]. note that in the area in which they conducted their research, Tete, Mozambique, basic services were available, but not certain contraception methods and termination of pregnancy. Public facilities face serious challenges in terms of space, staff, equipment, regular supplies and adequate provider practices. Private clinics offer some services, but at commercial prices.

In a study of healthcare preferences of sex workers in Kenya, South Africa and Mozambique, Lafort et al. [13] found that the most common factors in choice of care provider (most often public health facilities) was proximity and familiarity. Where targeted services were available, they were chosen because of the shorter waiting times, perceived quality of care, more privacy and friendlier personnel.

Positive Service Delivery

In this section, we report on studies outlining the development and implementation on services that show promise. The Diagonal Interventions for Fast-Forward Health (DIFFER) is a programme developed and piloted in India, Kenya, South Africa and Mozambique. It was aimed at improving targeted services for WSS and public health services, as well as cooperation between the two. Findings from a qualitative evaluation of the DIFFER intervention in Mozambique showed a significant increase in non-barrier contraceptive usage, with this increase being attributed to the WSS-targeted outreach rather than utilization of public health clinics [61]. While some public health facilities were reported to be WSS- friendly, barriers such as stock-outs, bribery, and disrespectful treatment remained in many. Lafort et al. [14] report that in all cities in which DIFFER was implemented, the uptake of services increased – from 12.5% to 41.5% in Durban, 25%–40.1% in Tete, and 44.9%–69.1% in Mombasa. In Tete and Mombasa, the rise in SRH service use was almost entirely due to greater uptake of targeted services. It was only in Durban that there was an increase in public health facility use.

In a different paper, Lafort et al. [40] reflect on the feasibility of up-scaling the DIFFER programme. Interviews with key informants—policymakers, government employees, international development or NGO workers and community representatives – revealed that expansion of targeted services were hampered by financial constraints, institutional capacity and lack of buy-in. In addition, making existing public services friendlier to key populations was preferred to the targeted approach.

Makhakhe and colleagues [29] report a similar finding concerning targeted services in South Africa. Participants felt that they could not consult public SRH services because of stigma. Instead, non-governmental health and advocacy organisations providing SRH services through mobile facilities or through peer interactions were seen as promoting trust and providing tailored services. The authors caution, however, that these services are provided in urban areas, leaving those outside of these sites vulnerable to the health risks associated with a lack of access of tailored services.

Ampt et al. [15] report on a randomised control trial that tested the efficacy of a multifaceted short messaging service intervention concerning contraceptive knowledge and behaviours (WHISPER) in reducing unintended pregnancies. When compared to the control (SHOUT—nutrition focused messages), the intervention had no measurable effect on unintended pregnancies (15.5 per 100 person-years compared to 14.7 per 100 person-years). They argue that, when used in isolation, these kinds of interventions will not have a significant impact on unintended pregnancies amongst sex workers.

Service delivery for WSS has largely concentrated on the prevention of HIV. These services, however, can have an effect on non-barrier contraceptive usage as well. For example, in an investigation of the effect of the Shikamana HIV programme in Tanzania, Kerrigan et al. [45] found increases in the use of modern contraception in follow-up visits.

Rosenberg et al. [37] outline the findings from a pilot programme targeted at refugee women who sell sex in Uganda. They indicate that taking a community empowerment approach can facilitate access to a range of critical information, services and support options in these circumstances. This approach includes information on how to use contraceptives, referrals for friendly HIV testing and treatment, peer counselling and protective peer networks.

Gichuna and colleagues [23] emphasise the importance of innovative approaches to supporting the health of WSS. For instance, their partner NGO, Bar Hostess Empowerment and Support Programme (BHESP), uses online platforms and phone technology to deliver peer information, advice and advocacy for sex workers; this is being enhanced to reach women who are mobile and transient. The phone app is paired with a flexible outreach model, using a motorcycle to deliver essential medications to WSS.

Discussion

Higher rates of contraceptive usage may be expected in studies reporting on targeted services. However, reportage of non-barrier contraceptive usage and unintended pregnancies were not associated with whether the study reported on a targeted service. Thus, thee variability of rates of contraception usage and unintended pregnancies points to the need for contextually relevant programmes based on knowledge of local usage patterns and needs, including rates amongst the general population, which also varies considerably: lifetime contraceptive usage in sub-Saharan Africa varies from 30% to 76% [62].

Dual contraception and emergency contraception can greatly reduce the incidence of unintended pregnancies. But use of dual contraception, for the most part, and emergency contraception, where reported, was shown to be low. Future pregnancy intentions were associated with having a non-paying partner, but not with HIV status. Knowledge of safer conception varied. Lack of referral networks and living in displaced persons camps were associated with unsafe abortion. Incarceration was associated with coerced abortion. Awareness of post-abortion care was reportedly low.

Reports of unintended pregnancies vary across the studies, but for the most part are higher than the average rate of reported unintended pregnancies across sub-Saharan Africa, which stands at 29% [63]. It is important, however, that country specific rates be considered in comparisons. For example, Luchters et al. [20] describe the rate of unintended pregnancies found in their Kenyan study (24%) as high. However, Mumah et al. [64] of the Kenyan Population Council indicate that “Levels of unintended pregnancy among Kenyan women have changed little over the last 5 years, declining from 45 percent in 2003 to just 43 percent in 2008/09” (non-paginated) [The latest Kenyan Demographic and Health Survey does not list the prevalence of unintended pregnancies]. In this case, thus, the participants in Luchters et al.’s study had lower rates of unintended pregnancies than did the general population of women of reproductive age.

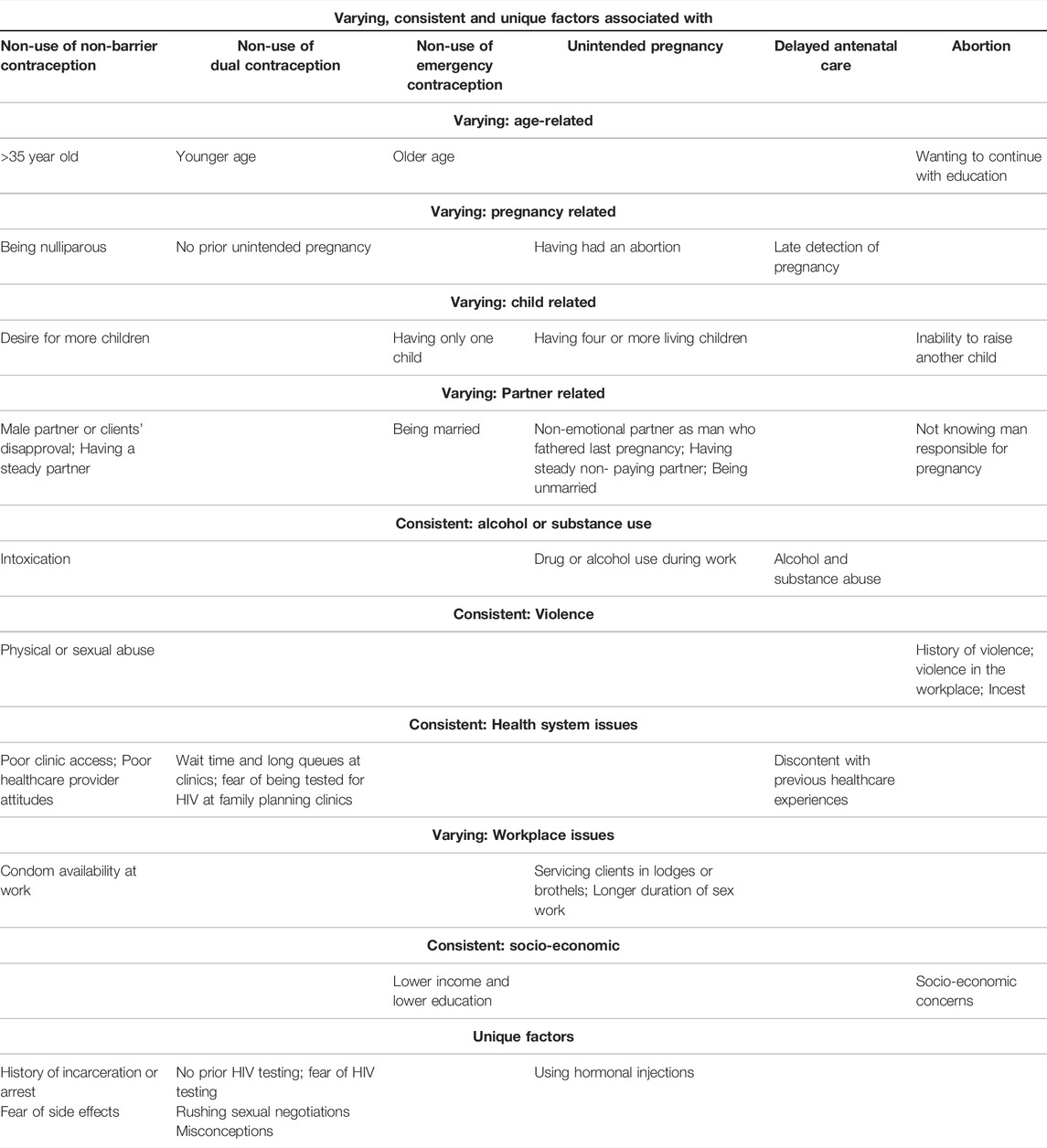

In Table 5, we consolidate the findings regarding factors relating to non-use of non-barrier, dual and emergency contraception, unintended pregnancies, delayed antenatal care, and abortion. It should be noted that some of the factors featured may apply in other areas, but were not featured in the studies under review. Varying factors refer to where the direction of the factor (e.g., older or younger age) is not consistent across the RH areas. Consistent factors are where the direction of the factor is the same across the areas. Unique factors feature in only one area (as outlined in the studies reviewed). Alcohol and substance use and abuse featured across three areas, violence over two, poor health systems over three, and socio-economic issues over two. This suggests that addressing alcohol use, violence, health systems problems across programmes may bear fruit, along with tackling poverty.

TABLE 5. Varying, consistent and unique factors (Women Who Sell Sex Project, Eastern and Southern Africa, 2010–2021).

Many barriers to services, probably exacerbated by COVID, were recorded. Some of these are systemic (e.g., long wait time, operating hours, paucity of available services), while other have to do with the service providers’ actions (e.g., WSS being asked for bribes, discrimination and stigmatisation against WSS). Some WSS reported experiencing violence by clients during pregnancy. Pregnancy affected their ability to work, while work negatively affected childcare.

Increase in non-barrier contraception usage was recorded in a diagonal intervention (targeted services together with improved public health services - DIFFER), but was attributed mainly to the targeted services. Focussed provision and promotion of non-barrier contraceptive methods in a simulated HIV vaccine efficacy trial led to significant increases in use.

Public Health Implications of Findings

Recommendations emanating from this review are as follows:

• Context is important in terms of designing services; this includes site of sex work, available public services, geographical location, and demographics of sex workers (e.g. age, mobility).

• Targeted approaches, including peer educators, outreach services, mobile clinics, phone apps, seem to bear fruit; given financial constraints in implementing these to scale, however, concurrent improvement of public health facilities’ services and access is important.

• Training of healthcare and social service providers in a rights-based approach to RH amongst WSS is important. This includes the creation of safe WSS friendly care.

• Counselling for safe conception and early pregnancy detection for women who desire children should be provided.

• Integrated links between HIV and sexual and reproductive health programmes should be created to support contraceptive uptake.

• Mentor mother programmes tailored for WSS should be developed.

• Programmes should address misconceptions regarding services (e.g., automatically being tested for HIV) and commodities (e.g., fear of contraceptive side effects).

• Community empowerment approaches are encouraged, including use of peer educators and the creation of joint strategies to reduce violence.

• Awareness of legal abortion services (within parameters allowed within the country), and of post-abortion care should be raised.

• Content and activities that are accessible to mobile WSS should be developed.

• Guidelines for accessing and servicing adolescent WSS should be developed.

• Alcohol and substance abuse, health system problems, and violence featured across a number of RH areas explored in this paper. This suggests that programmes tackling these issues may bear fruit.

In addition, research in under-served areas (e.g., rural areas), in countries in which there has been little or no knowledge production, and in relation to abortion is needed to flesh out context specific, comprehensive and relevant services.

Strengths and Limitations

This paper brings together the findings of many studies in relation to reproductive health amongst WSS. As such, it contributes to ongoing efforts to ensure that the reproductive rights of WSS are realised. It provides a road map for states as well as non-governmental organisations to ensure access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care of appropriate quality, in line with a reproductive rights approach.

There are, however, some limitations to this paper. Women who sell sex are a hard to reach population. Many of the studies reported on in this review drew on samples presenting at clinics, respondent-driven sampling, or convenience sampling. Possibilities for generalisation are thus limited. Additionally, studies were conducted in diverse contexts; caution should be taken in applying the findings across the region.

Conclusion

In line with a reproductive rights approach, women who sell sex are entitled to reproductive health services. This review has highlighted the multiple barriers that WSS experience in relation to these services, as well as the factors involved in non-use of contraception, unintended pregnancies, delayed antenatal care, and abortion. This information, along with studies showing what and how programmes targeted at WSS work, should be used to improve the reproductive health and rights of WSS in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Author Contributions

CM co-conceptualised the study, applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to identified papers, quality checked papers, co-conducted the analysis, wrote first draft of paper, finalised paper. JR conducted the search, applied inclusion/exclusion criteria to identified papers, quality checked papers, co-conducted the analysis, contributed to the write-up. RD co-conceptualised the study, commented on the first submission and contributed to revisions.

Funding

This work is based on research supported by the South African Research Chairs initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 20 87582), and the United Nations Population (UNFPA).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1Note of terminology: most public health publications use the term “female sex workers”. In this paper we prefer the person-first approach, using, line with others [65].

References

1.World Health Organization, Fund UNP. HIV/AIDS JUNP on, Implementing Comprehensive HIV/STI Programmes with Sex Workers. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

2. Starrs, AM, Ezeh, AC, Barker, G, Basu, A, Bertrand, JT, Blum, R, et al. Accelerate Progress-Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for All: Report of the Guttmacher- Lancet Commission. The Lancet (2018) 391:2642–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30293-9

3. Willis, B, Welch, K, and Onda, S. Health of Female Sex Workers and Their Children: A Call for Action. Lancet Glob Health (2016) 4:e438–e439. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30071-7

4. Ivanova, O, Dræbel, T, and Tellier, S. Are Sexual and Reproductive Health Policies Designed for All? Vulnerable Groups in Policy Documents of Four European Countries and Their Involvement in Policy Development. Int J Health Pol Manag (2015) 4:663–71. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.148

5. Dhana, A, Luchters, S, Moore, L, Lafort, Y, Roy, A, Scorgie, F, et al. Systematic Review of Facility-Based Sexual and Reproductive Health Services for Female Sex Workers in Africa. Glob Health (2014) 10:46–13. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-10-46

6. Scorgie, F, Chersich, MF, Ntaganira, I, Gerbase, A, Lule, F, and Lo, Y-R. Socio-demographic Characteristics and Behavioral Risk Factors of Female Sex Workers in Sub-saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav (2012) 16:920–33. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-9985-z

7. Shannon, K, Crago, A-L, Baral, SD, Bekker, L-G, Kerrigan, D, Decker, MR, et al. The Global Response and Unmet Actions for HIV and Sex Workers. The Lancet (2018) 392:698–710. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31439-9

8.World Health Organization (WHO). Human Rights and Health (2017). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health (Accessed Nov 13, 2021).

9. Arksey, H, and O'Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2005) 8:19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

10. Dulli, L, Field, S, Masaba, R, and Ndiritu, J. Addressing Broader Reproductive Health Needs of Female Sex Workers through Integrated Family Planning/HIV Prevention Services: A Non-randomized Trial of a Health-Services Intervention Designed to Improve Uptake of Family Planning Services in Kenya. PLoS One (2019) 14:e0219813–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219813

11. Long, JE, Waruguru, G, Yuhas, K, Wilson, KS, Masese, LN, Wanje, G, et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Unmet Contraceptive Need in HIV-Positive Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya. PLoS One (2019) 14:e0218291–1214. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218291

12. Robert, K, Maryline, M, Jordan, K, Lina, D, Helgar, M, Annrita, I, et al. Factors Influencing Access of HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Among Adolescent Key Populations in Kenya. Int J Public Health (2020) 65:425–32. doi:10.1007/s00038-020-01373-8

13. Lafort, Y, Greener, R, Roy, A, Greener, L, Ombidi, W, Lessitala, F, et al. Where Do Female Sex Workers Seek HIV and Reproductive Health Care and what Motivates These Choices? A Survey in 4 Cities in India, Kenya, Mozambique and South Africa. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0160730–14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160730

14. Lafort, Y, Greener, L, Lessitala, F, Chabeda, S, Greener, R, Beksinska, M, et al. Effect of a 'diagonal' Intervention on Uptake of HIV and Reproductive Health Services by Female Sex Workers in Three Sub-saharan African Cities. Trop Med Int Health (2018) 23:774–84. doi:10.1111/tmi.13072

15. Ampt, FH, Lim, MSC, Agius, PA, L'Engle, K, Manguro, G, Gichuki, C, et al. Effect of a mobile Phone Intervention for Female Sex Workers on Unintended Pregnancy in Kenya (WHISPER or SHOUT): a Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Glob Health (2020) 8:e1534–e1545. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30389-2

16. Lokken, EM, Wanje, G, Richardson, BA, Mutunga, E, Wilson, KS, Jaoko, W, et al. Brief Report: Incidence and Correlates of Pregnancy in HIV-Positive Kenyan Sex Workers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2020) 85:11–7. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000002402

17. Sutherland, EG, Alaii, J, Tsui, S, Luchters, S, Okal, J, King'ola, N, et al. Contraceptive Needs of Female Sex Workers in Kenya - A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur J Contraception Reprod Health Care (2011) 16:173–82. doi:10.3109/13625187.2011.564683

18. Ampt, FH, Lim, MSC, Agius, PA, Chersich, MF, Manguro, G, Gichuki, CM, et al. Use of Long‐acting Reversible Contraception in a Cluster‐random Sample of Female Sex Workers in Kenya. Int J Gynecol Obstet (2019) 146:184–91. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12862

19. Ochako, R, Okal, J, Kimetu, S, Askew, I, and Temmerman, M. Female Sex Workers Experiences of Using Contraceptive Methods: A Qualitative Study in Kenya. BMC Womens Health (2018) 18:105–10. doi:10.1186/s12905-018-0601-5

20. Luchters, S, Bosire, W, Feng, A, Richter, ML, King’ola, N, Ampt, F, et al. "A Baby Was an Added Burden": Predictors and Consequences of Unintended Pregnancies for Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya: A Mixed-Methods Study. PLoS One (2016) 11:e0162871–21. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162871

21. Wilson, KS, Wanje, G, Masese, L, Simoni, JM, Shafi, J, Adala, L, et al. A Prospective Cohort Study of Fertility Desire, Unprotected Sex, and Detectable Viral Load in HIV-Positive Female Sex Workers in Mombasa, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2018) 78:276–82. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000001680

22. Corneli, A, Lemons, A, Otieno-Masaba, R, Ndiritu, J, Packer, C, Lamarre-Vincent, J, et al. Contraceptive Service Delivery in Kenya: A Qualitative Study to Identify Barriers and Preferences Among Female Sex Workers and Health Care Providers. Contraception (2016) 94:34–9. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.004

23. Gichuna, S, Hassan, R, Sanders, T, Campbell, R, Mutonyi, M, and Mwangi, P. Access to Healthcare in a Time of COVID-19: Sex Workers in Crisis in Nairobi, Kenya. Glob Public Health (2020) 15:1430–42. doi:10.1080/17441692.2020.1810298

24. Slabbert, M, Venter, F, Gay, C, Roelofsen, C, Lalla-Edward, S, and Rees, H. Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes Among Female Sex Workers in Johannesburg and Pretoria, South Africa: Recommendations for Public Health Programmes. BMC Public Health (2017) 17:17–27. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4346-0

25. Rao, A, Baral, S, Phaswana-Mafuya, N, Lambert, A, Kose, Z, Mcingana, M, et al. Pregnancy Intentions and Safer Pregnancy Knowledge Among Female Sex Workers in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Obstet Gynecol (2016) 128:15–21. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001471

26. Parmley, L, Rao, A, Young, K, Kose, Z, Phaswana‐Mafuya, N, Mcingana, M, et al. Female Sex Workers' Experiences Selling Sex during Pregnancy and Post‐Delivery in South Africa. Stud Fam Plann (2019) 50:201–17. doi:10.1111/sifp.12090

27. Parmley, L, Rao, A, Kose, Z, Lambert, A, Max, R, Phaswana-Mafuya, N, et al. Antenatal Care Presentation and Engagement in the Context of Sex Work: Exploring Barriers to Care for Sex Worker Mothers in South Africa. Reprod Health (2019) 16:1–12. doi:10.1186/s12978-019-0716-7

28. Afzal, O, Lieber, M, and Beddoe, AM. Reproductive Healthcare Needs of Sex Workers in Rural South Africa: A Community Assessment. Ann Glob Heal (2020) 86:1–5. doi:10.5334/aogh.2706

29. Makhakhe, NF, Meyer-Weitz, A, Struthers, H, and McIntyre, J. The Role of Health and Advocacy Organisations in Assisting Female Sex Workers to Gain Access to Health Care in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res (2019) 19:1. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4552-9.10

30. Bukenya, JN, Wanyenze, RK, Barrett, G, Hall, J, Makumbi, F, and Guwatudde, D. Contraceptive Use, Prevalence and Predictors of Pregnancy Planning Among Female Sex Workers in Uganda: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2019) 19:1. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2260-4.11

31. Abaasa, A, Todd, J, Mayanja, Y, Price, M, Fast, PE, Kaleebu, P, et al. Use of Reliable Contraceptives and its Correlates Among Women Participating in Simulated HIV Vaccine Efficacy Trials in Key-Populations in Uganda. Sci Rep (2019) 9:1. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51879-2.10

32. Erickson, M, Goldenberg, SM, Ajok, M, Muldoon, KA, Muzaaya, G, and Shannon, K. Structural Determinants of Dual Contraceptive Use Among Female Sex Workers in Gulu, Northern Uganda. Int J Gynecol Obstet (2015) 131:91–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.029

33. Duff, P, Muzaaya, G, Muldoon, K, Dobrer, S, Akello, M, Birungi, J, et al. High Rates of Unintended Pregnancies Among Young Women Sex Workers in Conflict-Affected Northern Uganda: The Social Contexts of Brothels/Lodges and Substance Use. Afr J Reprod Health (2017) 21:64–72. doi:10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.8

34. Bukenya, JN, Nalwadda, CK, Neema, S, Kyambadde, P, Wanyenze, RK, and Barrett, G. Pregnancy Planning Among Female Sex Workers in Uganda: Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of the London Measure of Unplanned Pregnancy. Afr J Reprod Health (2019) 23:79–95. doi:10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i3.8

35. Marlow, HM, Shellenberg, K, and Yegon, E. Abortion Services for Sex Workers in Uganda: Successful Strategies in an Urban Clinic. Cult Health Sex (2014) 16:931–43. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.922218

36. Erickson, M, Goldenberg, SM, Akello, M, Muzaaya, G, Nguyen, P, Birungi, J, et al. Incarceration and Exposure to Internally Displaced Persons Camps Associated with Reproductive Rights Abuses Among Sex Workers in Northern Uganda. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care (2017) 43:201–9. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101492

37. Rosenberg, JS, and Bakomeza, D. Let's Talk about Sex Work in Humanitarian Settings: Piloting a Rights-Based Approach to Working with Refugee Women Selling Sex in Kampala. Reprod Health Matters (2017) 25:95–102. doi:10.1080/09688080.2017.1405674

38. Lafort, Y, Lessitala, F, Candrinho, B, Greener, L, Greener, R, Beksinska, M, et al. Barriers to HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health Care for Female Sex Workers in Tete, Mozambique: Results from a Cross-Sectional Survey and Focus Group Discussions. BMC Public Health (2016) 16. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3305-5

39. Lafort, Y, Jocitala, O, Candrinho, B, Greener, L, Beksinska, M, Smit, JA, et al. Are HIV and Reproductive Health Services Adapted to the Needs of Female Sex Workers? Results of a Policy and Situational Analysis in Tete, Mozambique. BMC Health Serv Res (2016) 16:1–10. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1551-y

40. Lafort, Y, Ismael De Melo, MS, Lessitala, F, Griffin, S, Chersich, M, and Delva, W. Feasibility, Acceptability and Potential Sustainability of a 'diagonal' Approach to Health Services for Female Sex Workers in Mozambique. BMC Health Serv Res (2018) 18. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3555-2

41. Mbita, G, Mwanamsangu, A, Plotkin, M, Casalini, C, Shao, A, Lija, G, et al. Consistent Condom Use and Dual Protection Among Female Sex Workers: Surveillance Findings from a Large-Scale, Community-Based Combination HIV Prevention Program in Tanzania. AIDS Behav (2020) 24:802–11. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02642-1

42. Faini, D, Munseri, P, Bakari, M, Sandström, E, Faxelid, E, and Hanson, C. "I Did Not Plan to Have a Baby. This Is the Outcome of Our Work": a Qualitative Study Exploring Unintended Pregnancy Among Female Sex Workers. BMC Women's Health (2020) 20:1–13. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-01137-9

43. Yam, EA, Kahabuka, C, Mbita, G, Winani, K, Apicella, L, Casalini, C, et al. Safer conception for Female Sex Workers Living with HIV in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: Cross-Sectional Analysis of Needs and Opportunities in Integrated Family Planning/HIV Services. PLoS One (2020) 15:e0235739–14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235739

44. Beckham, SW, Shembilu, CR, Brahmbhatt, H, Winch, PJ, Beyrer, C, and Kerrigan, DL. Female Sex Workers' Experiences with Intended Pregnancy and Antenatal Care Services in Southern Tanzania. Stud Fam Plann (2015) 46:55–71. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2015.00015.x

45. Kerrigan, D, Mbwambo, J, and Likindikoki, S. Let’s Stick Together: Community Empowerment Approach Significantly Impacts Multiple HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health Outcomes Among Female Sex Workers in Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc (2018) 21:e25148. doi:10.1002/jia2.25148

46. Yam, EA, Mnisi, Z, Mabuza, X, Kennedy, C, Tsui, A, and Baral, S. Use of Dual Protection Among Female Sex Workers in Swaziland. Ipsrh (2013) 39:069–78. doi:10.1363/3906913

47. Yam, EA, Mnisi, Z, Maziya, S, Kennedy, C, and Baral, S. Use of Emergency Contraceptive Pills Among Female Sex Workers in Swaziland. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care (2014) 40:102–7. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100527

48. Schwartz, SR, Papworth, E, Ky-Zerbo, O, Sithole, B, Anato, S, Grosso, A, et al. Reproductive Health Needs of Female Sex Workers and Opportunities for Enhanced Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission Efforts in Sub-saharan Africa. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care (2017) 43:50–9. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2014-100968

49. Twizelimana, D, and Muula, AS. Unmet Contraceptive Needs Among Female Sex Workers (FSWs) in Semi Urban Blantyre, Malawi. Reprod Health (2021) 18:1–8. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01064-w

50. Twizelimana, D, and Muula, AS. Correlates of Pregnancy Among Female Sex Workers (FSWs) in Semi Urban Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2020) 20:1–7. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03018-3

51. Twizelimana, D, and Muula, AS. Actions Taken by Female Sex Workers (FSWs) after Condom Failure in Semi Urban Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Womens Health (2020) 20:273–7. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-01142-y

52. Weldegebreal, R, Melaku, YA, Alemayehu, M, and Gebrehiwot, TG. Unintended Pregnancy Among Female Sex Workers in Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:1–10. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1366-5

53. Yam, EA, Kidanu, A, Burnett-Zieman, B, Pilgrim, N, Okal, J, Bekele, A, et al. Pregnancy Experiences of Female Sex Workers in Adama City, Ethiopia: Complexity of Partner Relationships and Pregnancy Intentions. Stud Fam Plann (2017) 48:107–19. doi:10.1111/sifp.12019

54. Kilembe, W, Inambao, M, Sharkey, T, Wall, KM, Parker, R, Himukumbwa, C, et al. Single Mothers and Female Sex Workers in Zambia Have Similar Risk Profiles. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses (2019) 35:814–25. doi:10.1089/aid.2019.0013

55. Chanda, MM, Ortblad, KF, Mwale, M, Chongo, S, Kanchele, C, Kamungoma, N, et al. Contraceptive Use and Unplanned Pregnancy Among Female Sex Workers in Zambia. Contraception (2017) 96:196–202. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.003

56. Sibanda, E, Shapiro, A, Mathers, B, Verster, A, Baggaley, R, Gaffield, ME, et al. Values and Preferences of Contraceptive Methods: a Mixed-Methods Study Among Sex Workers from Diverse Settings. Sex Reprod Health Matters (2021) 29:314–35. doi:10.1080/26410397.2021.1913787

57. Chareka, S, Crankshaw, TL, and Zambezi, P. Economic and Social Dimensions Influencing Safety of Induced Abortions Amongst Young Women Who Sell Sex in Zimbabwe. Sex Reprod Health Matters (2021) 29:121–32. doi:10.1080/26410397.2021.1881209

58. Kiernan, B, Mishori, R, and Masoda, M. 'There Is Fear but There Is No Other Work': a Preliminary Qualitative Exploration of the Experience of Sex Workers in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Cult Health Sex (2016) 18:237–48. doi:10.1080/13691058.2015.1073790

59. Srivatsan, V, Schwartz, S, Rao, A, Rolfe, J, Mpooa, N, Mothopeng, T, et al. Engagement in Antiretroviral Treatment and Modern Contraceptive Methods Among Female Sex Workers Living with HIV in Lesotho. Women's Reprod Health (2019) 6:204–21. doi:10.1080/23293691.2019.1619052

60. Ingabire, R, Parker, R, Nyombayire, J, Ko, JE, Mukamuyango, J, Bizimana, J, et al. Female Sex Workers in Kigali, Rwanda: a Key Population at Risk of HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and Unplanned Pregnancy. Int J STD AIDS (2019) 30:557–68. doi:10.1177/0956462418817050

61. Lafort, Y, Lessitala, F, Ismael de Melo, MS, Griffin, S, Chersich, M, and Delva, W. Impact of a "Diagonal" Intervention on Uptake of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services by Female Sex Workers in Mozambique: A Mixed-Methods Implementation Study. Front Public Health (2018) 6:1–12. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00109

62. Blackstone, SR, Nwaozuru, U, and Iwelunmor, J. Factors Influencing Contraceptive Use in Sub-saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Int Q Community Health Educ (2017) 37:79–91. doi:10.1177/0272684X16685254

63. Ameyaw, EK, Budu, E, Sambah, F, Baatiema, L, Appiah, F, Seidu, AA, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Unintended Pregnancy in Sub-saharan Africa: A Multi- Country Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. PLoS One (2019) 14 (8):e0220970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220970

64. Mumah, J, Kabiru, CW, and Izugbara, CO. Kenya Country Profile : A Status Check on Unintended Pregnancy in Kenya EVIDENCE BRIEF. Nairobi: Population Council (2014).

Keywords: pregnancy, sex workers, contraception, abortion, Eastern Africa, Southern Africa

Citation: Macleod CI, Reynolds JH and Delate R (2022) Women Who Sell Sex in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Scoping Review of Non-Barrier Contraception, Pregnancy and Abortion. Public Health Rev 43:1604376. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2022.1604376

Received: 30 July 2021; Accepted: 15 February 2022;

Published: 11 May 2022.

Edited by:

Paula Meireles, University Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Inês Baía, University of Porto, PortugalCopyright © 2022 Macleod, Reynolds and Delate. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Catriona Ida Macleod, Yy5tYWNsZW9kQHJ1LmFjLnphJiN4MDIwMGE7

Catriona Ida Macleod

Catriona Ida Macleod John Hunter Reynolds

John Hunter Reynolds Richard Delate3

Richard Delate3