- 1Unit of Clinical and Health Psychology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

- 2The Department of Psychology and Social Sciences, Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Jounieh, Lebanon

Objectives: The mental health crisis among young adults in Lebanon, worsened by events like the Beirut Blast and economic instability, requires urgent attention. Globally, 10%–20% of individuals aged 18–29 face mental health challenges, with many also experiencing physical pain. Despite growing evidence of the bidirectional relationship between mental health and pain, this intersection remains underexplored in Lebanon, especially compared to WEIRD countries. This scoping review examines the relationship between physical pain and mental health issues—anxiety, depression, and stress—among Lebanese youth.

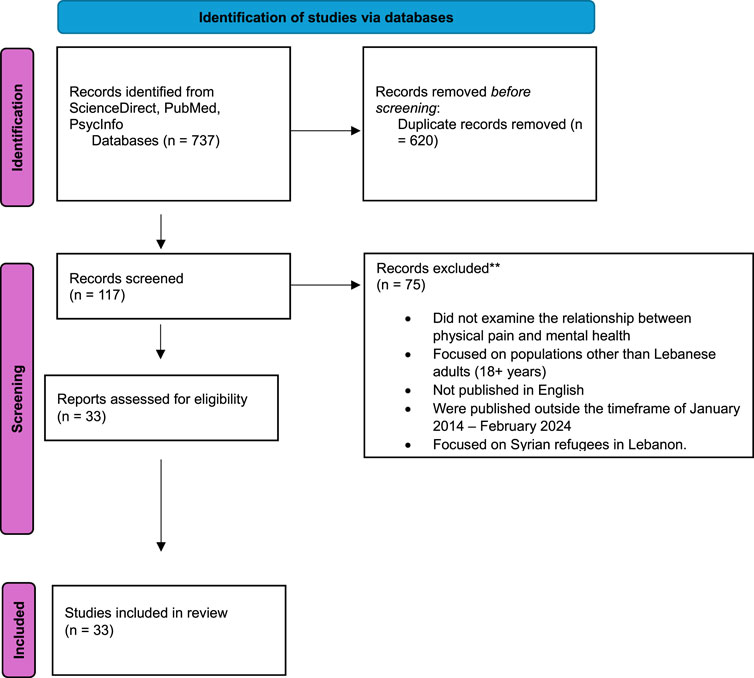

Methods: A systematic review of studies from January 2014 to February 2024 was conducted by screening PubMed, PsychInfo, and ScienceDirect. A total of 33 studies were included.

Results: The findings indicate a bidirectional link between mental health and physical pain. University students (36.1% of studies) were particularly impacted, and 81% of studies reported higher pain prevalence among females. Additionally, mindfulness meditation was identified as a potential protective factor, although it remains underexplored in Lebanon.

Conclusion: Addressing these gaps supports tailored interventions for Lebanese youth and enriches our understanding of mental health in non-WEIRD contexts.

Introduction

Mental health challenges among youth aged 18–29 have become a critical global concern, with 10%–20% of this demographic experiencing significant mental health issues [1]. This concern is particularly acute in Lebanon, where ongoing economic crises, political instability, and the aftermath of traumatic events such as the 2020 Beirut explosion and the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated mental health struggles among the youth [2]. Lebanese youth are increasingly affected by severe mental health problems, including stress, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3]. The International Labor Organization reports a staggering 23% unemployment rate among Lebanese youth [4], further adding to their financial and psychological burdens. Prior to the current crisis, approximately 25% of young adults in Lebanon experienced high rates of PTSD, with prevalent conditions such as depression (12.6%) and anxiety (16.7%) [5, 6]. Additionally, exposure to frequent violent conflict has left 70% of the population traumatized [7], with a significant proportion of young individuals reporting major depressive disorder, stress-related issues and other anxiety-related conditions [8].

In addition to mental health issues, physical pain has emerged as a major health problem among young populations globally, with around 54% of them reporting physical pain annually [9]. In WEIRD countries (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), common symptoms of physical pain were found to be headaches (8%–83%) and abdominal pain (4%–53%), followed by musculoskeletal pain (4%–40%) and back pain (12%–24%) [10]. According to the Global Burden of Disease, physical pain was the second-highest contributor to global disability in 2018, with 1.9 billion people affected by recurring conditions such as headaches, low back pain, and neck pain—recognized as leading causes of disability [11, 12].

Physical pain was shown to be often associated with mental health issues, such as stress, anxiety and depression [13]. Individuals with depression, stress or anxiety report experiencing physical pain, and the presence of physical pain can also hinder the treatment of mental health conditions [13, 14]. Pereira et al. found that individuals with physical pain were four times more likely to suffer from stress, anxiety or depression than those without pain (Odds ratio [OR] = 4.1) [15]. Conditions such as back pain and stress, anxiety or depression significantly increase the risk of disability, and the co-occurrence of these issues exacerbates this risk [16, 17]. Most of the research on the relationship between mental health and physical pain has been well-documented in the WEIRD cultural contexts where healthcare access, cultural norms, and stressors differ significantly from those in non-WEIRD countries particularly in Middle Eastern regions like Lebanon that are affected by recurrent crises and ongoing wars.

Despite growing recognition of the link between mental health and physical pain, research within the Lebanese youth population remains scarce. Available studies suggest a high prevalence of physical pain conditions such as lower back pain (44.8% in Lebanese workers aged 20–64 [18]) and migraines (35.8% in young adults aged 18–29 [19]). However, these studies do not comprehensively explore the mental health correlates of physical pain in Lebanon’s youth. While evidence from India (non-WEIRD nation) and Switzerland (WEIRD nation) suggests strong links between stress, anxiety, depression, and pain [20], the extent to which these findings apply to Lebanon remains unclear. Given Lebanon’s unique sociopolitical stressors, including economic collapse and exposure to trauma [21], a scoping review is needed to consolidate existing data and identify key gaps. Most existing studies have been conducted in high-income, resource-rich settings, which do not accurately reflect Lebanon’s reality. Therefore, there is a pressing need for research to understand the interconnections between mental health and physical pain within the Lebanese context, particularly among the youth who are bearing the brunt of the country’s crises. This scoping review aims to systematically explore the relationship between physical pain and mental health issues among Lebanese youth. Specifically, it will examine the association between pain and conditions such as anxiety, depression, and stress—links that are well-documented in WEIRD countries but remain underexplored in Lebanon. By synthesizing existing research, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how physical pain may be linked to mental health challenges in the Lebanese context. This will not only shed light on an understudied area but also provide valuable insights for future research, interventions, and support services tailored to improve both the physical and mental wellbeing of the youth in Lebanon.

Methods

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews) guidelines. A systematic literature search was performed across three major databases—PubMed, PsychInfo, and ScienceDirect—to identify studies investigating the relationship between physical pain and mental health issues in Lebanese youth (aged 18 years and above).

Search Strategy and Keywords

The search terms included “somatic symptoms,” “chronic pain,” “musculoskeletal pain,” “physical aches,” “somatization/somatization,” “somatic distress,” “mental health related somatic symptoms,” “unexplained medical symptoms,” “Lebanese youth,” “emergent youth/adult,” “adults in Lebanon,” “Lebanese adults,” “mental health disorders,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “stress,” “Lebanese youth,” and “non-WEIRD populations.” The search spanned January 2014 to February 2024 and included peer-reviewed studies written in English. Grey literature, conference abstracts, and case studies were excluded to maintain methodological rigor.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they i) studies that showed the relationship between physical pain and mental health ii) focused on Lebanese adults only (over 18 years of age), iii) were published in English, and iv) were published between January 2014 – February 2024. Studies were excluded if they: i) focused on Syrian refugees in Lebanon and ii) did not assess the interaction between mental health and physical pain. Rationale for Exclusion of Syrian Refugees: Syrian refugees in Lebanon face unique socio-economic conditions, mental health challenges, and barriers to higher education that differ significantly from the broader Lebanese young adult population. Their experiences of displacement, trauma, and limited healthcare access introduce distinct stressors that fall outside the scope of this review. To ensure a focused analysis on Lebanese young adults, studies on refugee populations were excluded.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

After screening 737 studies, 33 met inclusion criteria. The lead author (TT) conducted the initial screening, with a second reviewer (YR) verifying selected studies. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Data extracted included study design, sample size, pain type, mental health outcomes, and key findings.

Data Analysis

After screening and checking the articles for eligibility based on hand-searched, we found a total of 33 articles that were exported to excel. This was carried out by the lead author (TT), with decisions reviewed by second author (YR). Where discrepancies in classification existed, the article in question was discussed and agreement reached between authors. We present our results in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Results

Search Results

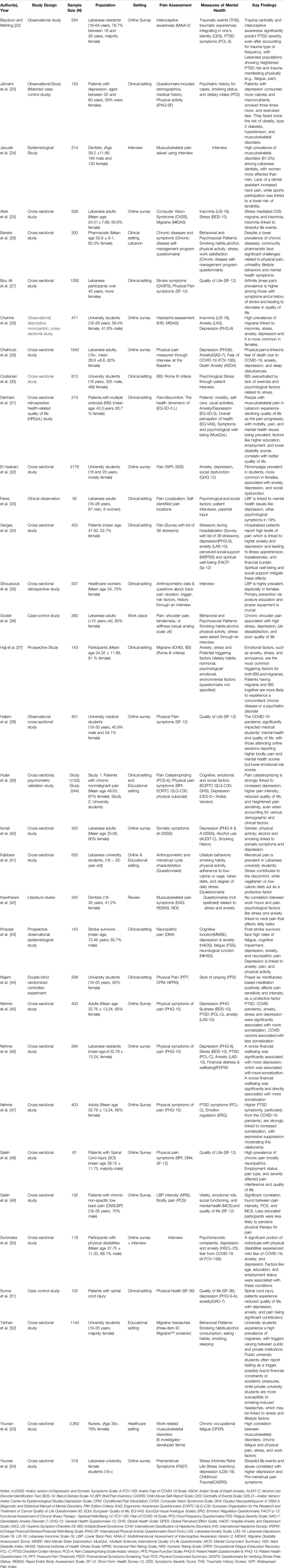

A total of 33 studies were included in this review, summarizing the relationship between physical pain and mental health problems. The study selection process is depicted in Figure 1, and the characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1. Among these, 13 studies (36%) were conducted on university students between 18 and 26 years of age [22, 25, 28, 30, 32, 33, 38, 40–42, 44, 52, 54] while the remaining 23 studies (63.8%) examined individuals diagnosed with chronic pain and healthcare professionals, such as nurses [23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 31, 34–37, 39, 43, 44, 46, 48–51, 53, 55–57]. Of the included studies, 29 (81%) had majority of females participants [22, 23, 25–32, 34–37, 39–42, 44–47, 52–57] and in 30 studies (83.3%), quantitative self-report measures were the most common method of assessing physical pain and mental health [24, 26–30, 32, 34, 35, 37–49, 51, 53–57].

Only six studies adopted a qualitative approach using open-ended questionnaires to evaluate physical pain [23, 31, 33, 36, 50, 52].

Types of Physical Pain and the Tools Used to Assess

The review identified various types of physical pain frequently reported among participants, particularly university students and females. The most common types of pain included: musculoskeletal pain [24, 53], neck and lower back pain [35, 42, 48], migraine [25, 28, 52], and menstrual pain [41, 54]. These findings suggest that physical pain is highly prevalent among university students, with a particularly high burden among female participants [28, 30, 32, 38, 40, 52]. In these studies, the physical pain was measured using Premenstrual Symptoms Screening Tool (PSST) [54], Depression and Somatic Symptoms Scale (A-DSSS) [40], Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Arabic Version (PCS-A) [39], Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [46], Neck Disability Index (NDI), Numeric rating scale (NRS) [42, 44, 48] Arabic version of Brief Pain Inventory (BPI-A) [39, 48], Beirut Distress Scale (BDS-10) [25], Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness Version 2 (MAIA-2) [22], Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [27, 38], Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire (DN4) [39, 48], Migraine disability assessment test (MIDAS) [25, 28], standardized self-reported questionnaire to measure Irritable Bowel Syndrome [30], Widespread pain index (WPI) and Symptoms severity score (SSS) [32].

Mental Health Problems Associated With Physical Pain

A strong association between physical pain and mental health problems was observed across all included studies. The most frequently reported mental health concerns were stress, depression and anxiety that were strongly related to physical pain [25, 28, 30–34, 36, 42, 53]. In some of the studies, they acted as a predictor [25, 42, 53, 54], while in others they were the consequence of physical pain [31, 32, 34, 41]. This is in line with many studies conducted on pain [58–62]. Interestingly, only one study reported mindfulness meditation as a protective factor against the development of pain [44].

Gender Differences in Pain and Mental Health

Gender differences were evident in both the prevalence and intensity of physical pain and mental health symptoms. Female participants reported significantly higher levels of pain, particularly menstrual pain and migraines, which were associated with increased depressive symptoms [28, 32, 40].

Assessment Methods Used: Gaps and Limitations

Most studies reviewed relied heavily on quantitative measures [37, 38, 45, 46, 54], to assess pain and other mental health problems, with only 2 studies employing a mixed-methods approach [23, 50] that combined both qualitative and quantitative data. Additionally, only a few studies utilized the well-validated Arabic version of the scales like A-DSSS) [40], PCS-A [39], BDS-10 [25], and BPI-A [39, 48], emphasizing a significant gap in the cultural validation of assessment tools.

Discussion

This scoping review addresses a significant research gap by examining the relationship between physical pain and mental health issues among young people in Lebanon—a non-WEIRD nation affected by ongoing conflict and recurring crises. By focusing on Lebanon, our study aims to deepen understanding of physical pain and its mental health associations within diverse cultural settings, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive global perspective on the relationship between physical and mental health in underrepresented populations.

One major finding from this review is the strong bidirectional relationship between various types of physical pain, particularly among university students in Lebanon, and mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and stress [25,42]. This pattern aligns with previous research conducted in Switzerland [63] and India [64] which also showed similar relationships among university students. In some studies, mental health issues such as stress, depression, and anxiety were identified as predictors of physical pain [25, 42, 53, 54] while in others, they appeared to result from physical pain [31, 32, 34, 41]. These findings resonate with broader research indicating that chronic pain and mental health often interact in a cyclical way, where pain worsens mental health issues, and vice versa [58–62].

Approximately 36% of the studies included in this review focused specifically on university students aged 18–26 [22, 28, 30]. Among these students, the most common forms of pain reported were musculoskeletal pain [24, 53], neck and lower back pain [35, 42, 48], migraine [28, 52], and menstrual pain [41, 54]. The prevalence of these types of pain highlights unique vulnerabilities within this demographic, potentially stemming from academic stress, lifestyle factors, or societal expectations [65, 66]. The remaining 64% of studies [5, 23, 44] involved individuals with chronic pain and healthcare professionals, like nurses, who might experience high levels of work-related stress and physical strain [67, 68].

A notable finding from these studies is the demographic focus, as 81% of studies had a majority of female participants [32, 36, 37]. This gender disparity in the experience and reporting of pain is consistent with previous literature, which often suggests that women tend to report higher levels of both acute and chronic pain [69–71]. Various factors may contribute to this trend, including biological differences, such as hormonal fluctuations that can influence pain sensitivity [72, 73], as well as psychosocial factors, such as differing gender norms related to expressing pain [74, 75]. In many cultures, including Lebanon, women may feel more socially permitted to express pain and seek help [76], while men may face societal expectations to endure pain quietly due to norms around masculinity [77]. Additionally, research suggests that women are more likely to experience somatic symptoms associated with mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, which could further explain the higher reported prevalence of physical pain among females [78–81]. These findings underscore the importance of considering gender-specific factors when assessing and treating physical pain and mental health issues among young people, as this can lead to more targeted and effective interventions.

Furthermore, the 83.3% of the studies predominantly used quantitative self-report measures to assess physical pain and mental health [24,40,41]. The measurement tools to assess and mental health problems included scales such as the PSST [54], A-DSSS [40], BDS-10 [25], PCS-A [39], PHQ-9 [47], NRS [42, 44, 48], BPI-A [39, 48], MAIA-2 [22], SF-36 [27, 38], DN4 [39, 48], MIDAS [25, 28], WPI [32] and SSS [32]. These tools provide standardized metrics for assessing pain levels and mental health symptoms, although the review points out a lack of culturally validated tools for use in Lebanese populations. Only a few studies used the culturally validated versions of established tools like the A-DSSS, BDS-10, PCS-A, and BPI-A [25, 39, 40, 48], emphasizing a significant gap in culturally appropriate assessment methods. In addition, these quantitative measures, may not fully capture the culturally specific experiences of pain and mental health [82]. Pain can be expressed differently across cultures [83, 84] and relying solely on quantitative methods or tools designed for WEIRD populations risks overlooking culturally nuanced experiences of pain and mental health issues [85]. In the context of Lebanon, a non-WEIRD population, there is a crucial need for culturally adapted instruments. Moreover, incorporating qualitative methods would provide a more in-depth understanding of how pain is experienced and expressed within this cultural context [86], potentially leading to more accurate and relevant assessments. This gap underscores the importance of expanding research methodologies to ensure the tools used are both culturally sensitive and inclusive, particularly when addressing mental health and pain in diverse populations.

An intriguing finding was the emergence of mindfulness meditation as a potential protective factor, identified in only one study [44]. Despite extensive literature supporting mindfulness as effective in reducing chronic pain and improving mental health outcomes [87–89] this approach appears underexplored in the Lebanese context. This suggests that mindfulness could represent an untapped resource for managing comorbid physical and mental health conditions among Lebanese youth, warranting further investigation.

In summary, this scoping review highlights a substantial association between physical pain and mental health problems among young adults in Lebanon. It also reveals limitations in current methodologies and stresses the need for culturally validated tools. By adopting a more holistic, gender-sensitive, and culturally inclusive approach, future research can better capture the complex experiences of physical pain and mental health in Lebanon, ultimately leading to more effective and targeted mental health strategies for these populations.

Limitations

Despite its contributions, this scoping review merits limitations. First, most studies focused on quantitative measures, limiting the depth of understanding regarding the lived experiences of pain among youth in Lebanon. The lack of qualitative research also hampers the ability to explore culturally specific expressions of pain. Second, while this review highlights gender differences in the experience of pain, it does not account for other important factors, such as socioeconomic status, that could influence these experiences. Third, due to indexing limitations, studies examining associations between mental health and physical pain that did not include specific keywords in their titles or abstracts may have been overlooked. Additionally, the search strategy was not formally validated or reviewed by a librarian. However, the search terms were carefully developed based on relevant keywords and were guided by the specific aims of the review. Furthermore, we acknowledge that our inclusion criteria did not explicitly differentiate between clinical and community studies or consider grey literature and unpublished studies. This decision was made with the primary aim of understanding the relationship between physical pain and mental health within the Lebanese context, rather than focusing on study setting or type, and to maintain rigor and reliability in the data. Future reviews could address this limitation by expanding the search strategy to include a broader range of pain-related measures or by incorporating grey literature to capture a wider array of relevant studies. Fourth, we did not conduct a formal calibration exercise for data abstraction questions, nor did we calculate the kappa agreement between the two reviewers. While both reviewers independently screened the studies, any disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus. The absence of a formal kappa calculation may limit the ability to quantify the level of agreement between reviewers. In future reviews, we would like to implement a calibration process and calculate Cohen’s kappa to ensure greater consistency and reliability in the data abstraction process.

Author Contributions

TT and YR screened the studies. TT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TT and YR jointly revised the manuscript based on the CMS comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project is funded by the Research Partnership Grants 2023 (Grant No.: RPG-2023-44). Funded by Leading House (LH) for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Generative AI Statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. We acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s ChatGPT to assist in refining certain sections of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used for rephrasing sentences and enhancing readability. The final content was reviewed, revised, and approved by all authors to ensure accuracy and originality.

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental Health: Strengthening Our Response (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response. (Accessed June 17, 2022).

2. Mourani, SC, and Ghreichi, MC. Mental Health Reforms in Lebanon during the Multifaceted Crisis. Arab Reform Initiative (2021). Available online at: https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/mental-health-reforms-in-lebanon-during-the-multifaceted-crisis/. (Accessed September 28, 2021).

3. El Zouki, CJ, Chahine, A, Mhanna, M, Obeid, S, and Hallit, S. Rate and Correlates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Following the Beirut Blast and the Economic Crisis Among Lebanese University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry (2022) 22(1):532. doi:10.1186/s12888-022-04180-y

4. Werlen, B. International Year of Global Understanding. An Interview with Benno Werlen (2015). Available online at: http://www.j-reading.org/index.php/geography/article/view/120. (Accessed December 22, 2015).

5. Al-Hajj, S, Mokdad, AH, and Kazzi, A. Beirut Explosion Aftermath: Lessons and Guidelines. Emerg Med J (2021) 38(12):938–9. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-210880

6. Hackl, A, and Najdi, W. Online Work as Humanitarian Relief? The Promise and Limitations of Digital Livelihoods for Syrian Refugees and Lebanese Youth during Times of Crisis. Environ Plann a Economy Space (2023) 56(1):100–16. doi:10.1177/0308518x231184470

7. Farhood, L, Dimassi, H, and Lehtinen, T. Exposure to War-Related Traumatic Events, Prevalence of PTSD, and General Psychiatric Morbidity in a Civilian Population from Southern Lebanon. J Transcultural Nurs (2006) 17(4):333–40. doi:10.1177/1043659606291549

8. Karam, EG, Friedman, MJ, Hill, ED, Kessler, RC, McLaughlin, KA, Petukhova, M, et al. Cumulative Traumas and Risk Thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the World Mental Health (WMH) Surveys. Depress Anxiety (2013) 31(2):130–42. doi:10.1002/da.22169

9. Ando, S, Yamasaki, S, Shimodera, S, Sasaki, T, Oshima, N, Furukawa, TA, et al. A Greater Number of Somatic Pain Sites Is Associated with Poor Mental Health in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry (2013) 13(1):30. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-30

10. Kirtley, OJ, O’Carroll, RE, and O’Connor, RC. Pain and Self-Harm: A Systematic Review. J Affective Disord (2016) 203:347–63. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.068

11. James, RJE, Walsh, DA, and Ferguson, E. Trajectories of Pain Predict Disabilities Affecting Daily Living in Arthritis. Br J Health Psychol (2019) 24(3):485–96. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12364

12. Vos, CJ, Verhagen, AP, Passchier, J, and Koes, BW. Clinical Course and Prognostic Factors in Acute Neck Pain: An Inception Cohort Study in General Practice. Pain Med (2008) 9(5):572–80. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00456.x

13. Arnow, BA, Hunkeler, EM, Blasey, CM, Lee, J, Constantino, MJ, Fireman, B, et al. Comorbid Depression, Chronic Pain, and Disability in Primary Care. Psychosomatic Med (2006) 68(2):262–8. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc

14. Bair, MJ, Robinson, RL, Katon, W, and Kroenke, K. Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review. Arch Intern Med (2003) 163(20):2433–45. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433

15. Pereira, FG, França, MH, De Paiva, MCA, Andrade, LH, and Viana, MC. Prevalence and Clinical Profile of Chronic Pain and its Association with Mental Disorders. Revista De Saúde Pública (2017) 51:96. doi:10.11606/S1518-8787.2017051007025

16. Dorner, TE, Alexanderson, K, Svedberg, P, Tinghög, P, Ropponen, A, and Mittendorfer-Rutz, E. Synergistic Effect between Back Pain and Common Mental Disorders and the Risk of Future Disability Pension: ANationwide Study from Sweden. Psychol Med (2015) 46(2):425–36. doi:10.1017/S003329171500197X

17. Zhu, B, Zhao, Z, Ye, W, Marciniak, MD, and Swindle, R. The Cost of Comorbid Depression and Pain for Individuals Diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. The J Nervous Ment Dis (2009) 197(2):136–9. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181963486

18. Bawab, W, Ismail, K, Awada, S, Rachidi, S, Hajje, AH, and Salameh, P. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Low Back Pain Among Office Workers in Lebanon. Int J Occup Hyg (2015) 7(2):45–52. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280713236_Prevalence_and_Risk_Factors_of_Low_Back_Pain_among_Office_Workers_in_Lebanon. (Accessed October 14, 2015).

19. Mosleh, R, Hatem, G, Navasardyan, N, Ajrouche, R, Zein, S, and Awada, S. Triggering and Relieving Factors of Migraine Among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study in Lebanon. Deleted J (2022) 13(4):257–64. doi:10.48208/headachemed.2022.31

20. Tandon, T, Piccolo, M, Ledermann, K, McNally, RJ, Gupta, R, Morina, N, et al. Mental Health Markers and Protective Factors in Students with Symptoms of Physical Pain across WEIRD and Non-WEIRD Samples – A Network Analysis. BMC Psychiatry (2024) 24(1):318. doi:10.1186/s12888-024-05767-3

21. Harake, W, Jamali, I, and Abou Hamde, N (2020). The Deliberate Depression. Lebanon Economic Monitor.

22. Beydoun, H, and Mehling, W. Traumatic Experiences in Lebanon: PTSD, Associated Identity and Interoception. Eur J Trauma and Dissociation (2023) 7(4):100344. doi:10.1016/j.ejtd.2023.100344

23. Jahrami, H, Saif, Z, AlHaddad, M, Faris, MAI, Hammad, L, and Ali, B. Assessing Dietary and Lifestyle Risk Behaviours and Their Associations with Disease Comorbidities Among Patients with Depression: A Case-Control Study from Bahrain. Heliyon (2020) 6(6):e04323. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04323

24. Jaoude, S, Naaman, N, Nehme, E, Gebeily, J, and Daou, M. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Pain Among Lebanese Dentists: An Epidemiological Study. Niger J Clin Pract (2017) 20(8):1002–9. doi:10.4103/njcp.njcp_401_16

25. Akiki, M, Obeid, S, Salameh, P, Malaeb, D, Akel, M, Hallit, R, et al. Association between Computer Vision Syndrome, Insomnia, and Migraine Among Lebanese Adults: The Mediating Effect of Stress. The Prim Care Companion CNS Disord (2022) 24(4):21m03083. doi:10.4088/pcc.21m03083

26. Barake, S, Tofaha, R, Rahme, D, and Lahoud, N. The Health Status of Lebanese Community Pharmacists: Prevalence of Poor Lifestyle Behaviors and Chronic Conditions. Saudi Pharm J (2021) 29(6):497–505. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2021.04.005

27. Bou Ali, I, Farah, R, Zeidan, RK, Chahine, MN, Sayed, GA, Asmar, R, et al. Stroke Symptoms Impact on Mental and Physical Health: A Lebanese Population Based Study. Revue Neurologique (2020) 177(1–2):124–31. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2020.03.026

28. Chahine, S, Wanna, S, and Salameh, P. Migraine Attacks Among Lebanese University Medical Students: A Cross Sectional Study on Prevalence and Correlations. J Clin Neurosci (2022) 100:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2022.03.039

29. Chalhoub, Z, Koubeissy, H, Fares, Y, and Abou-Abbas, L. Fear and Death Anxiety in the Shadow of COVID-19 Among the Lebanese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE (2022) 17(7):e0270567. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0270567

30. Costanian, C, Tamim, H, and Assaad, S. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome Among University Students in Lebanon: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study. World J Gastroenterol (2015) 21(12):3628–35. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3628

31. Dahham, J, Hiligsmann, M, Kremer, I, Khoury, SJ, Darwish, H, Hosseini, H, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Utilities Among Lebanese Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Mult Scler Relat Disord (2024) 86:105635. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2024.105635

32. El Hasbani, G, Ibrahem, M, Haidous, M, Chaaya, M, and Uthman, IW. Fibromyalgia Among University Students: A Vulnerable Population. Mediterr J Rheumatol (2022) 33(4):407–12. doi:10.31138/mjr.33.4.407

33. Fares, MY, Fares, J, Salhab, HA, Khachfe, HH, Bdeir, A, and Fares, Y. Low Back Pain Among Weightlifting Adolescents and Young Adults. Cureus (2020) 12:e9127. doi:10.7759/cureus.9127

34. Gerges, S, Hallit, R, and Hallit, S. Stressors in Hospitalized Patients and Their Associations with Mental Health Outcomes: Testing Perceived Social Support and Spiritual Well-Being as Moderators. BMC Psychiatry (2023) 23(1):323. doi:10.1186/s12888-023-04833-6

35. Ghoussoub, K, Asmar, AE, Kreichati, G, Wakim, S, Bakhache, M, Baz, M, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Low Back Pain Among Hospital Staff in a University Hospital in Lebanon. Ann Phys Rehabil Med (2016) 59:e146. doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2016.07.325

36. Godah, M, Chaaya, M, Slim, Z, and Uthman, I. Risk Factors for Incident Shoulder Soft Tissue Rheumatic Disorders: A Population-Based Case–Control Study in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J (2018) 24(4):393–400. doi:10.26719/2018.24.4.393

37. Hajj, A, Mourad, D, Ghossoub, M, Hallit, S, Geagea, A, Abboud, H, et al. Uncovering Demographic, Clinical, Triggering Factors Similarities between Migraine and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The J Nervous Ment Dis (2019) 207(10):847–53. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000001033

38. Hatem, G, Omar, CA, Ghanem, D, Khachman, D, Rachidi, S, and Awada, S. Evaluation of the Impact of Online Education on the Health-Related Quality of Life of Medical Students in Lebanon. Educación Médica (2023) 24(3):100812. doi:10.1016/j.edumed.2023.100812

39. Huijer, HAS, Fares, S, and French, DJ. The Development and Psychometric Validation of an Arabic-Language Version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Pain Res Manage (2017) 2017:1472792–7. doi:10.1155/2017/1472792

40. Ismail, A, Chabbouh, A, Charro, E, Masri, JE, Ghazi, M, Sadier, NS, et al. Examining the Validity and Reliability of the Arabic Translated Version of the Depression and Somatic Symptoms Scale (A-DSSS) Among the Lebanese Adults. Scientific Rep (2024) 14(1):5435. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55813-z

41. Kabbara, R, Ziade, F, and Gannagé-Yared, MH. Prevalence and Etiology of Menstrual Disorders in Lebanese University Students. Int J Gynecol and Obstet (2014) 126(2):177–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.01.010

42. Kawtharani, AA, Msheik, A, Salman, F, Younes, AH, and Chemeisani, A. A Survey of Neck Pain Among Dentists of the Lebanese Community. Pain Res Manage (2023) 2023:8528028–14. doi:10.1155/2023/8528028

43. Khazaal, W, Taliani, M, Boutros, C, Abou-Abbas, L, Hosseini, H, Salameh, P, et al. Psychological Complications at 3 Months Following Stroke: Prevalence and Correlates Among Stroke Survivors in Lebanon. Front Psychol (2021) 12:663267. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663267

44. Najem, C, Meeus, M, Cagnie, B, Ayoubi, F, Achek, MA, Van Wilgen, P, et al. The Effect of Praying on Endogenous Pain Modulation and Pain Intensity in Healthy Religious Individuals in Lebanon: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Religion Health (2023) 62(3):1756–79. doi:10.1007/s10943-022-01714-2

45. Nehme, A, Barakat, M, Malaeb, D, Obeid, S, Hallit, S, and Haddad, G. Association between COVID-19 Symptoms, COVID-19 Vaccine, and Somatization Among a Sample of the Lebanese Adults. Pharm Pract (2023) 21(1):2763–6. doi:10.18549/pharmpract.2023.1.2763

46. Nehme, A, Moussa, S, Fekih-Romdhane, F, Hallit, S, Obeid, S, and Haddad, G. The Mediating Role of Depression in the Association Between Perceived Financial Wellbeing and Somatization: A Study in the Context of Lebanon’s Financial Crisis. Int J Environ Health Res (2024) 35:22–36. doi:10.1080/09603123.2024.2341132

47. Nehme, A, Moussa, S, Fekih-Romdhane, F, Yakın, E, Hallit, S, Obeid, S, et al. Expressive Suppression Moderates the Relationship between PTSD from COVID-19 and Somatization and Validation of the Arabic Version of Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15). PLoS ONE (2024) 19(1):e0293081. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0293081

48. Saleh, NEH, Fneish, S, Orabi, A, Al-Amin, G, Naim, I, and Sadek, Z. Chronic Pain Among Lebanese Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury: Pain Interference and Impact on Quality of Life. Curr J Neurol (2023) 22(4):238–48. doi:10.18502/cjn.v22i4.14529

49. Saleh, NEH, Hamdan, Y, Shabaanieh, A, Housseiny, N, Ramadan, A, Diab, AH, et al. Global Perceived Improvement and Health-Related Quality of Life After Physical Therapy in Lebanese Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil (2023) 36(6):1421–8. doi:10.3233/bmr-220423

50. Summaka, M, Zein, H, Naim, I, and Fneish, S. Assessing the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak and its Related Factors on Lebanese Individuals with Physical Disabilities. Disabil Health J (2021) 14(3):101073. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101073

51. Sunna, T, Elias, E, Summaka, M, Zein, H, Elias, C, and Nasser, Z. Quality of Life Among Men with Spinal Cord Injury in Lebanon: A Case Control Study. Neurorehabilitation (2019) 45(4):547–53. doi:10.3233/nre-192916

52. Tahhan, Z, Hatem, G, Abouelmaty, AM, Rafei, Z, and Awada, S. Design and Validation of an Artificial Intelligence-Powered Instrument for the Assessment of Migraine Risk in University Students in Lebanon. Comput Hum Behav Rep (2024) 15:100453. doi:10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100453

53. Younan, L, Clinton, M, Fares, S, Jardali, FE, and Samaha, H. The Relationship between Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders, Chronic Occupational Fatigue, and Work Organization: A Multi-hospital Cross-sectional Study. J Adv Nurs (2019) 75(8):1667–77. doi:10.1111/jan.13952

54. Younes, Y, Hallit, S, and Obeid, S. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder and Childhood Maltreatment, Adulthood Stressful Life Events and Depression Among Lebanese University Students: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. BMC Psychiatry (2021) 21(1):548. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03567-7

55. Ahmadieh, H, Basho, A, Chehade, A, Mallah, AA, and Dakour, A. Perception of Peri-Menopausal and Postmenopausal Lebanese Women on Osteoporosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Clin and Translational Endocrinol (2018) 14:19–24. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2018.10.001

56. El-Ali, Z, Kassas, GE, Ziade, FM, Shivappa, N, Hébert, JR, Zmerly, H, et al. Evaluation of Circulating Levels of Interleukin-10 and Interleukin-16 and Dietary Inflammatory Index in Lebanese Knee Osteoarthritis Patients. Heliyon (2021) 7(7):e07551. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07551

57. Zgheib, H, Wakil, C, Shayya, S, Kanso, M, Chebl, RB, Bachir, R, et al. Retrospective Cohort Study on Clinical Predictors for Acute Abnormalities on CT Scan in Adult Patients with Abdominal Pain. Eur J Radiol Open (2020) 7:100218. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2020.01.007

58. Kazeminasab, S, Nejadghaderi, SA, Amiri, P, Pourfathi, H, Araj-Khodaei, M, Sullman, MJM, et al. Neck Pain: Global Epidemiology, Trends and Risk Factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord (2022) 23(1):26. doi:10.1186/s12891-021-04957-4

59. Lerman, SF, Rudich, Z, Brill, S, Shalev, H, and Shahar, G. Longitudinal Associations between Depression, Anxiety, Pain, and Pain-Related Disability in Chronic Pain Patients. Psychosomatic Med (2015) 77(3):333–41. doi:10.1097/psy.0000000000000158

60. Riska, H, Karppinen, J, Heikkala, E, Villberg, J, and Hautala, AJ. Gender-Stratified Analysis of Psychosocial Factors and Physical Function in Higher Education Students with Musculoskeletal Pain. Eur J Physiother (2024) 6:1–7. doi:10.1080/21679169.2024.2386358

61. Robertson, D, Kumbhare, D, Nolet, P, Srbely, J, and Newton, G. Associations between Low Back Pain and Depression and Somatization in a Canadian Emerging Adult Population. J Can Chiropr Assoc (2017) 61(2):96–105.

62. Serbic, D, Zhao, J, and He, J. The Role of Pain, Disability and Perceived Social Support in Psychological and Academic Functioning of University Students with Pain: An Observational Study. Int J Adolesc Med Health (2021) 33(3):209–17. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2019-0032

63. Tandon, T, Ledermann, K, Gupta, R, Morina, N, Wadji, DL, Piccolo, M, et al. The Relationship between Behavioural and Mood Responses to Monetary Rewards in a Sample of Students with and without Reported Pain. Humanities Social Sci Commun (2022) 9(1):30. doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01044-4

64. Tandon, T, Piccolo, M, Ledermann, K, Gupta, R, Morina, N, and Martin-Soelch, C. Relationship between Behavioral and Mood Responses to Monetary Rewards in a Sample of Indian Students with and without Reported Pain. Scientific Rep (2022) 12(1):20242. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-24821-2

65. Ji-Hoon, K. Stress and Coping Mechanisms in South Korean High School Students: Academic Pressure, Social Expectations, and Mental Health Support. J Res Social Sci Humanities (2024) 3(5):45–54. doi:10.56397/jrssh.2024.05.09

66. Zhou, B, Mui, LG, Li, J, Yang, Y, and Hu, J. A Model for Risk Factors Harms and of Smartphone Addiction Among Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Nurse Education Pract (2024) 75:103874. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2024.103874

67. Vinstrup, J, Jakobsen, MD, and Andersen, LL. Perceived Stress and Low-Back Pain Among Healthcare Workers: A Multi-Center Prospective Cohort Study. Front Public Health (2020) 8:297. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00297

68. Sharma, S, Shrestha, N, and Jensen, MP. Pain-Related Factors Associated with Lost Work Days in Nurses with Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Scand J Pain (2016) 11(1):36–41. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2015.11.007

69. Dao, TT, and LeResche, L. Gender Differences in Pain. J Orofacial Pain. 2000 Summer (2000) 14(3):169–95. ; discussion 184-95. PMID: 11203754.

70. Mogil, JS. Sex Differences in Pain and Pain Inhibition: Multiple Explanations of a Controversial Phenomenon. Nat Rev Neurosci (2012) 13(12):859–66. doi:10.1038/nrn3360

71. Osborne, NR, and Davis, KD. Sex and Gender Differences in Pain. Int Rev Neurobiol (2022) 164:277–307. doi:10.1016/bs.irn.2022.06.013

72. Delaruelle, Z, Ivanova, TA, Khan, S, Negro, A, Ornello, R, Raffaelli, B, et al. Male and Female Sex Hormones in Primary Headaches. The J Headache Pain (2018) 19(1):117. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0922-7

73. Pieretti, S, Di Giannuario, A, Di Giovannandrea, R, Marzoli, F, Piccaro, G, Minosi, P, et al. Gender Differences in Pain and its Relief. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanita (2016) 52(2):184–9. doi:10.4415/ANN_16_02_09

74. Bartley, EJ, and Fillingim, RB. Sex Differences in Pain: A Brief Review of Clinical and Experimental Findings. Br J Anaesth (2013) 111(1):52–8. doi:10.1093/bja/aet127

75. Samulowitz, A, Gremyr, I, Eriksson, E, and Hensing, G. “Brave Men” and “Emotional Women”: A Theory-Guided Literature Review on Gender Bias in Health Care and Gendered Norms towards Patients with Chronic Pain. Pain Res Manage (2018) 2018:6358624–14. doi:10.1155/2018/6358624

76. Makhoul, M, Noureddine, S, Huijer, HAS, Farhood, L, Fares, S, Uthman, I, et al. Psychometric Properties of the Arabic Version of the Pain Resilience Scale Among Lebanese Adults with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Res Manage (2024) 2024(1):7361038. doi:10.1155/2024/7361038

77. Berke, DS, Reidy, DE, Miller, JD, and Zeichner, A. Take It Like a Man: Gender-Threatened Men’s Experience of Gender Role Discrepancy, Emotion Activation, and Pain Tolerance. Psychol Men and Masculinity (2016) 18(1):62–9. doi:10.1037/men0000036

78. Haug, TT, Mykletun, A, and Dahl, AA. The Association Between Anxiety, Depression, and Somatic Symptoms in a Large Population: The HUNT-II Study. Psychosomatic Med (2004) 66(6):845–51. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000145823.85658.0c

79. Tsang, A, Von Korff, M, Lee, S, Alonso, J, Karam, E, Angermeyer, MC, et al. Common Chronic Pain Conditions in Developed and Developing Countries: Gender and Age Differences and Comorbidity with Depression-Anxiety Disorders. J Pain (2008) 9(10):883–91. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

80. Velly, AM, and Mohit, S. Epidemiology of Pain and Relation to Psychiatric Disorders. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry (2018) 87:159–67. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.012

81. Weiss, SJ, Simeonova, DI, Kimmel, MC, Battle, CL, Maki, PM, and Flynn, HA. Anxiety and Physical Health Problems Increase the Odds of Women Having More Severe Symptoms of Depression. Arch Women S Ment Health (2016) 19(3):491–9. doi:10.1007/s00737-015-0575-3

82. Choe, R, Lardier, DT, Hess, JM, Blackwell, MA, Amer, S, Ndayisenga, M, et al. Measuring Culturally and Contextually Specific Distress Among Afghan, Iraqi, and Great Lakes African Refugees. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2024) 94(3):246–61. doi:10.1037/ort0000718

83. Ayaz, NP, and Sherman, DW. The Similarities and Differences of Nurse-Postoperative Patient Dyads’ Attitudes, Social Norms, and Behaviors Regarding Pain and Pain Management. J PeriAnesthesia Nurs (2024) 39(5):795–801. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2023.12.010

84. Sussex, R, and Evans, S. Communicating Medical Chronic Pain in an Intercultural Context. In: The Handbook of Cultural Linguistics. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore (2024). p. 51–69.

85. Rajkumar, RP. The Relationship between National Cultural Dimensions, Maternal Anxiety and Depression, and National Breastfeeding Rates: An Analysis of Data from 122 Countries. Front Commun (2023) 8. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2023.966603

86. Luckett, T, Davidson, PM, Green, A, Boyle, F, Stubbs, J, and Lovell, M. Assessment and Management of Adult Cancer Pain: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Recent Qualitative Studies Aimed at Developing Insights for Managing Barriers and Optimizing Facilitators within a Comprehensive Framework of Patient Care. J Pain Symptom Manage (2013) 46(2):229–53. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.021

87. Cherkin, D. Overcoming Challenges to Implementing Mindfulness-Based Pain Interventions. JAMA Intern Med (2024) 184(10):1174–5. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2024.3952

88. Lazaridou, A, Paschali, M, Edwards, R, Wilkins, T, Maynard, M, and Curiel, M. Adjunctive Mindfulness during Opioid Tapering for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Study Protocol of a Pilot Randomized Control Trial. The J Pain (2024) 25(4):32. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2024.01.152

Keywords: mental health, physical pain, Lebanese youth, depression, anxiety and stress

Citation: Tandon T, Rouhana Y, Rahme E, Zalaket N and Martin-Soelch C (2025) Youth Mental Health in Crisis: Understanding the Relationship Between Mental Health and Physical Pain in Lebanon’s Youth – A Scoping Review. Int. J. Public Health 70:1608156. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2025.1608156

Received: 13 November 2024; Accepted: 08 April 2025;

Published: 17 April 2025.

Edited by:

Franco Mascayano, New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI), United StatesReviewed by:

Three reviewers who chose to remain anonymousCopyright © 2025 Tandon, Rouhana, Rahme, Zalaket and Martin-Soelch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tanya Tandon, dGFueWEudGFuZG9uQHVuaWZyLmNo

Tanya Tandon

Tanya Tandon Yara Rouhana2

Yara Rouhana2 Chantal Martin-Soelch

Chantal Martin-Soelch