- 1Academic-Practice-Partnership between School of Health Professions at Bern University of Applied Sciences and University Hospital of Bern, Bern University of Applied Sciences, Bern, Switzerland

- 2Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 3Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+), Zurich, Switzerland

- 4Institute on Ageing, School of Health Professions, Bern University of Applied Sciences, Bern, Switzerland

- 5Swiss Sleep House Bern, Department of Neurology, University Hospital of Bern, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 6Interdisciplinary Sleep-Wake-Epilepsy-Center, University Hospital of Bern, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Objectives: As life expectancy rises at a faster rate than healthy life expectancy, there is a global need for scalable and cost-effective interventions that enhance the health-related quality of life of older adults. This study aimed to examine the user experience and usability of a 12-week digital multidomain lifestyle intervention in community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and above.

Methods: The intervention was developed involving older adults and delivered through a mobile application (app) focusing on physical activity, nutrition, sleep and mindfulness/relaxation. We used a mixed methods sequential explanatory approach to evaluate the user experience and usability of the intervention. We delivered online questionnaires before and after the intervention, collected app usage data and conducted semi-structured interviews.

Results: One hundred eight older adults participated in the study. Fifty-six percent of participants completed the 12-week intervention. Users who completed the intervention experienced it as highly satisfactory and rated the usability as high. User engagement was particularly high for the physical activity content.

Conclusion: Although participant retention can be a challenge, a digital multidomain lifestyle intervention developed involving community-dwelling older adults can lead to positive user experience and high usability.

Introduction

Lifestyle behaviour contributes to healthy aging with lifestyle influencing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and longevity [1]. Although life expectancy and healthy life expectancy are growing globally, healthy life expectancy is increasing at a lower rate than life expectancy [2]. A healthy lifestyle may extend healthy life expectancy, as a healthy lifestyle appears to be associated with an increase in the number of years lived without major chronic disease [3]. Furthermore, a healthy lifestyle, even in late life, can greatly mitigate the genetic risk of a shorter lifespan [4, 5]. Consequently, older adults should be enabled to adopt a healthy lifestyle.

Lifestyle medicine is an evidence-based discipline that follows a biopsychosocial approach, focusing on six key domains: sleep, nutrition, physical activity, stress, abuse of risky substances, and social relationships [6]. Lifestyle interventions that are based on the concept of lifestyle medicine place the individual at the centre and take a holistic view of their daily lives [7]. Multidomain lifestyle interventions (MLIs) address several domains as part of one intervention. In older adults, MLIs were shown to improve important dimensions of HRQoL [8], maintain daily functioning [9], and reduce cognitive decline [10–12], sarcopenia [13], inflammation levels [13] and the risk of developing new chronic diseases [14]. Self-efficacy for healthy lifestyle behaviour was also positively influenced by a lifestyle intervention [15]. Furthermore, a MLI was shown to be cost-effective in preventing dementia [16].

Most MLIs for older adults focused on two lifestyle domains, physical activity and nutrition [10, 17]. However, another lifestyle domain with an important contribution to healthy aging is sleep [18]. This domain has been less frequently included in MLIs [19]. Diverse sleep problems, including sleep apnea, insomnia, restless legs and excessive daytime sleepiness, show a high prevalence in older adults [20] and are associated with reduced health and quality of life [21, 22]. Furthermore, several lifestyle factors such as physical activity [23], nutrition [24], social relationships [25] and mindfulness [26, 27] seem to influence sleep quality in older adults. Mindfulness-based interventions also have the potential to positively influence quality of life and cognition in older adults [28–30]. Additionally, a recent qualitative review highlighted the development of new perspectives based on mindfulness-based interventions in older adults, including enhanced coping with negative situations, greater acceptance and an increased ability to focus on the present moment [31].

The two main modes of delivery for MLIs are face-to-face and digital [32]. Digital MLIs offer various advantages, including the flexibility to be used anytime and anywhere, personalization and low costs [19, 33]. These advantages address some important barriers and facilitators to implementing MLIs among community-dwelling older adults [34]. Digital MLIs are available in different formats, such as websites, mobile applications or a combination of both [19]. Most digital MLIs focus on the impact of measures including weight, body mass index (BMI), minutes of physical activity, daily step count or clinical parameters (e.g., blood pressure or cholesterol levels) but much less on HRQoL or mental wellbeing [33, 35]. However, HRQoL is an important patient reported outcome measure that is related to physical, mental and social aspects [36]. Mental wellbeing is another concept that is associated with HRQoL [37]. A recent study showed increases in domains of HRQoL and mental wellbeing with a 10-week digital MLI in a general adult population [38]. Furthermore, the effectiveness of digital MLIs on physical activity, nutrition, sleep and brain health outcomes in various populations has been shown in recent meta-analyses [19, 33]. In addition, there is evidence that older adults engage in digital mental wellbeing interventions [39]. However, there is a lack of digital MLIs targeting HRQoL and mental wellbeing that have been developed and evaluated involving older adults and address the sleep and stress domain [19, 33].

Therefore, this study aimed to examine the user experience and usability of a 12-week digital MLI that has been developed involving community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and older, and incorporated four lifestyle domains (physical activity, nutrition, sleep and mindfulness/relaxation) to improve HRQoL and mental wellbeing.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods study using a sequential explanatory approach to further investigate and interpret quantitative results through qualitative data [40].

Setting, Participants and Recruitment

Community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and older who understand German were included. Furthermore, access to a smartphone or tablet (Android-Version 10 or Apple iOS-Version 13 or later) was an inclusion criterion. Existing disabilities or diseases were not used as exclusion criteria. The intervention was home-based, with no online or in-person meetings. In case of any questions, participants could contact the research staff via the contact form in the app or email.

We used chain referral sampling to recruit diverse older adults in the German-speaking region of Switzerland. The study invitation and the eligibility criteria were announced via print, email, social media, or on the corresponding website of the research project, Senior Citizens’ Universities, senior platforms and websites, senior associations, and service providers for older people in Switzerland. A link to a website with further information was embedded in this invitation. On this website, interested individuals could leave their contact details. An email with all the details of the study, including the instructions for installing the app, was sent to all interested individuals. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants could withdraw at any time without giving reasons. Nonparticipation did not entail any disadvantages. The respondents were assured pseudonymized data handling. Participants were recruited from August to November 2023.

Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention

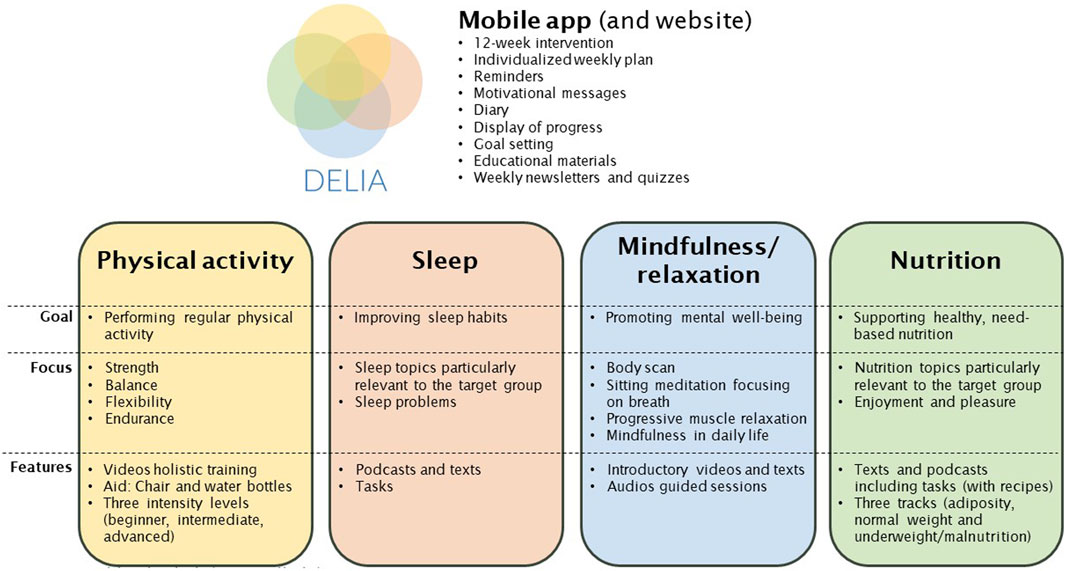

In this project, we examined a 12-week digital MLI with four core domains: physical activity, nutrition, sleep and mindfulness/relaxation. The intervention was delivered through a mobile application. In parallel, a website containing all the intervention content was developed to allow viewing on larger screens and to enable offline access through downloads. Figure 1 gives an overview of the main content; details can be found in Supplementary Appendix Section S1.

The overall purpose of the intervention was to increase HRQoL and mental wellbeing by enabling and empowering older adults to cultivate a deliberate and healthy lifestyle. Physical activity and nutrition content was provided over 12 weeks, whereas the content for sleep and mindfulness/relaxation lasted 6 weeks. Although it has been recommended to extend the number of lifestyle domains included in digital MLIs [19], user engagement of such interventions depends on the relationship between perceived benefits and costs [41]. The more lifestyle domains a MLI covers, the higher the costs in terms of time required to spend on the MLI. Time constraints have been reported as a common reason for dropping out of digital MLIs [19], therefore, we wanted to keep the time required to spend on our digital MLI on a reasonable level and decided to provide the content for sleep and mindfulness/relaxation sequentially, both lasting 6 weeks, rather than in parallel. To investigate the user experience related to these two less common lifestyle domains, we used a cross-over interventional design in which group A received access to modules related to physical activity, nutrition, and mindfulness/relaxation during the first six weeks, whereas the module mindfulness/relaxation was replaced by sleep the following 6 weeks and vice versa in group B.

Each user had an individually tailored structured weekly schedule of activities based on the information entered at the beginning. In addition, both the content of the physical activity and nutrition domains were personalized. The physical activity domain consisted of a multicomponent exercise training twice a week and recommendations for endurance training twice a week. The exercise training comprised videos and focused on strength in the upper and lower limbs and core as well as balance and flexibility. One session lasted between 20 and 40 min. The endurance training started with a duration of 15 min and gradually increased to 45 min. Several sample aerobic activities were proposed and the recommended intensity followed aerobic training zones including rating of perceived exertion (5–6) (modified Borg CR10 Scale [42]). The nutrition domain offered information, advice and tips on nutrition in older age twice a week, each session lasting 5–25 min. The sleep domain provided knowledge, advice and guidance for improving sleep habits. Two sessions per week of 5–20 min each were scheduled. In addition, participants were asked to complete a sleep protocol for 2 weeks. The mindfulness/relaxation domain introduced participants to evidence-based stress management techniques that have been shown to enhance mental wellbeing [43, 44]. We included three techniques: body scan, sitting meditation focusing on breath and progressive muscle relaxation. Each technique was practiced for 2 weeks. Two sessions per week 20 min each were scheduled, but participants were informed that these techniques could be practiced more regularly. If participants completed a session, they were asked to mark it as complete in the app. In addition, the intervention included weekly newsletters and quizzes. The time required for the intervention varied from person to person, but it was approximately three to four hours per week. Participants were onboarded to the intervention via email. This email included detailed participant information, instructions on how to install the mobile application and a short overview of the main functions of the mobile application. In case of questions or issues, they could contact the study team via email or the app (details Supplementary Appendix Section S1).

Sustainable implementation has been identified as a key challenge for digital health interventions [19, 45] that may be successfully addressed by thoroughly involving end-users during the development and evaluation of such interventions [45, 46]. Therefore, we used a user-centred design approach to develop the intervention, meaning that an iterative design process involving end-users (i.e., older adults) was applied in the design of the digital MLI [47]. This can also be considered as a participatory co-creation approach [48] (details Supplementary Appendix Section S2).

Furthermore, we used a multidisciplinary approach [45] and involved experienced health professionals and researchers from various disciplines including sleep, nutrition and dietetics, physiotherapy, exercise and sports science, mindfulness, psychology, gerontology, and software development. In addition, our intervention was mainly based on the following behaviour change technique clusters [49]: goals and planning, feedback and monitoring, shaping knowledge, repetition and substitution, comparison of behaviour and natural consequences. The development of the interventional content was based on available literature (including previous research from the study team [50]) and current recommendations of national and international institutions (e.g., the Swiss Society for Nutrition and the World Health Organization).

Mixed Methods

Quantitative Part

Assessments

All participants completed a self-administered online questionnaire before the start of the intervention. During the intervention, daily app usage data and participant feedback submitted via the contact form in the app or email were collected. After the intervention, participants were again asked to complete an online questionnaire. Furthermore, all participants who stopped using the app before the end of the intervention were contacted and asked to provide reasons for stopping in a short online questionnaire. All online questionnaires were created using LimeSurvey (LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany, Version 2.56.1).

Measures

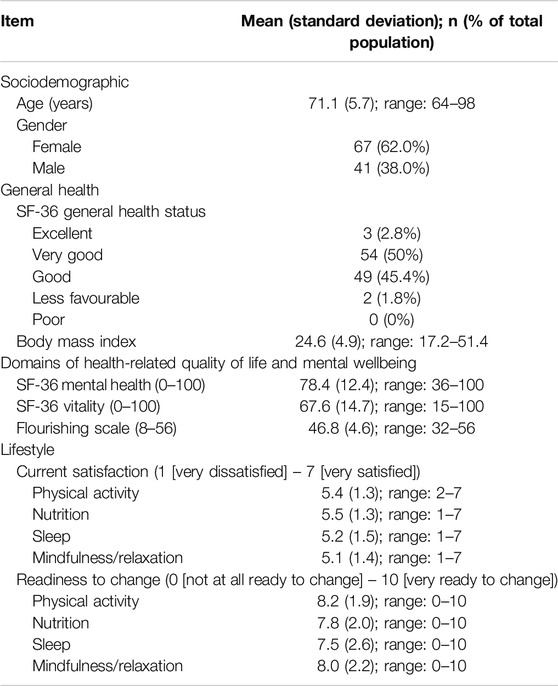

Participant characteristics: We collected data regarding age, gender, height, weight, general health status using SF-36 [51], current satisfaction with each lifestyle domain (self-developed; 7-point Likert scale, 1 [very dissatisfied], 7 [very satisfied]) and readiness to change (based on [52]; 11-point Likert scale, 0 [not at all ready to change], 10 [very ready to change]).

User Experience: User experience was defined according to Wesselman et al. [19]. Daily app usage data was automatically tracked during the intervention. This means the app documented the date and time an app domain (i.e., weekly plan, diary, newsletter and quiz, progress, help and safety and settings) was visited, a participant marked a session as complete and a diary entry was made. Overall satisfaction with the app was assessed with the following two statements from the mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (see below): “Overall, I am satisfied with this app.” and “I would use this app again.” using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree). In addition, participants who finished the intervention were asked if the app helped to move regularly/to eat healthy and according to their needs/to improve their sleep habits/to improve their mental wellbeing on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree). These questions were self-developed and we used the Likert scale similar to the mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (see below). In addition, weekly overall self-reported health was assessed within the app using the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ VAS) [53].

Usability: The app usability was assessed with the mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ) for standalone apps after the intervention was completed [54]. This questionnaire has 18 statements, and each has to be rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree). The MAUQ has three subscales: ease of use, interface satisfaction and usefulness. The German version of the MAUQ showed an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α = 0.93 and demonstrated high reliability [55].

Analysis

Questionnaire and usage data were summarized using numbers and percentages for qualitative variables, mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables with normal distribution and median as well as 25th/75th percentiles for quantitative variables with non-normal distribution.

Qualitative Part

Assessments

After the 12-week intervention, in-depth semi-structured interviews (one-on-one by phone) with randomly invited participants from the subgroup who completed the intervention were conducted in German until saturation was reached. Interviews were recorded in Microsoft Teams (Microsoft, Redmond, United States, Version 2023.38.01.50).

Measures

We developed an interview guide exploring user experience, usability, and ideas for improvement (details Supplementary Appendix Section S3.).

Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and a thematic analysis was performed [56]. Each interview transcript was first read in its entirety. They were then re-read and initially coded using comparative methods also considering quantitative results. In the next step, specific research team meetings were scheduled to review the initial coding. During these meetings, we focused on frequent initial codes or codes with a high significance for the research topic, searched for relationships between the initial codes, connected them and created categories.

Data Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Parts

The quantitative and qualitative parts were connected at the intermediate stage, where the results of the data analysis of the quantitative part informed and guided the data collection of the qualitative part [57]. At the interpretation and reporting level, data integration and presentation followed the four-stage technique of the Pillar Integration Process to get to a joint display of quantitative and qualitative findings [58].

Pre-Post Comparison of Effectiveness Measures

To investigate the potential effectiveness of the intervention on important dimensions of HRQoL and mental wellbeing, we used the mental health and vitality subscales from the SF-36 [51] and the flourishing scale [59]. The SF-36 has been recommended particularly in community-dwelling older adults with limited morbidity to assess detailed aspects of HRQoL [60]. SF-36 subscales range from 0 to 100, where 100 represents maximum mental health and vitality, respectively. The flourishing scale has been used in a recent study investigating the effectiveness of a digital MLI for adults [61] and the scale ranges from 8 (minimum) to 56 (maximum flourishing). Changes from pre-to post-intervention were analysed using paired t-tests (adjusted for multiple comparisons) in the subsample of participants who used the app until the end (12 weeks) and completed the post-intervention questionnaire (n = 57). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.3 for Windows).

Sample Size

Based on the sample size of quantitative studies investigating similar interventions [62–64], our experience from recruiting for a needs assessment for digital lifestyle interventions in Swiss community-dwelling older adults [50] and the planned duration of the recruitment phase (4 months) the target total sample size was 100 participants with 50 in each group.

Results

Participants

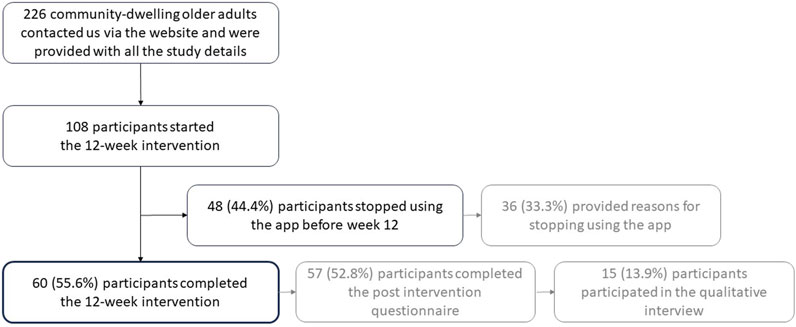

One hundred eight community-dwelling older adults participated in the study, 52 in group A and 56 in group B (Figure 2). Interviews were conducted with 15 participants and the interviews lasted between 20.4 and 42.0 min (mean 32.2 min, SD 6.8 min). Key baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1; details can be found in Supplementary Appendix Section S4.1. The most common reasons for study participation were an interest in lifestyle and wellbeing (seven interviewees), curiosity about the app (four interviewees) and an interest in technical aspects (two interviewees).

User Experience

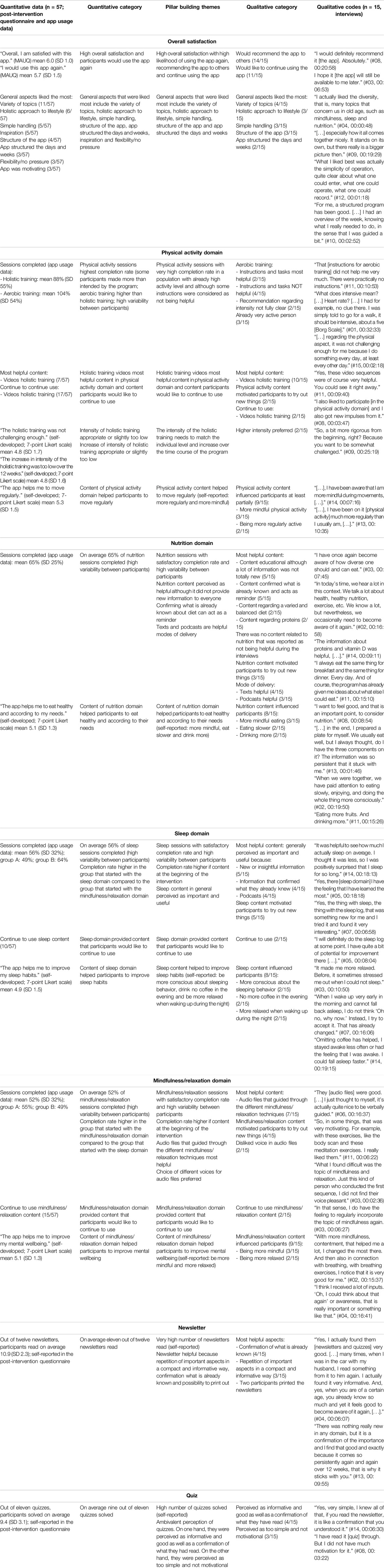

Detailed results from both the quantitative and qualitative research, data integration and pillar building themes are presented in Table 2.

Participant Retention

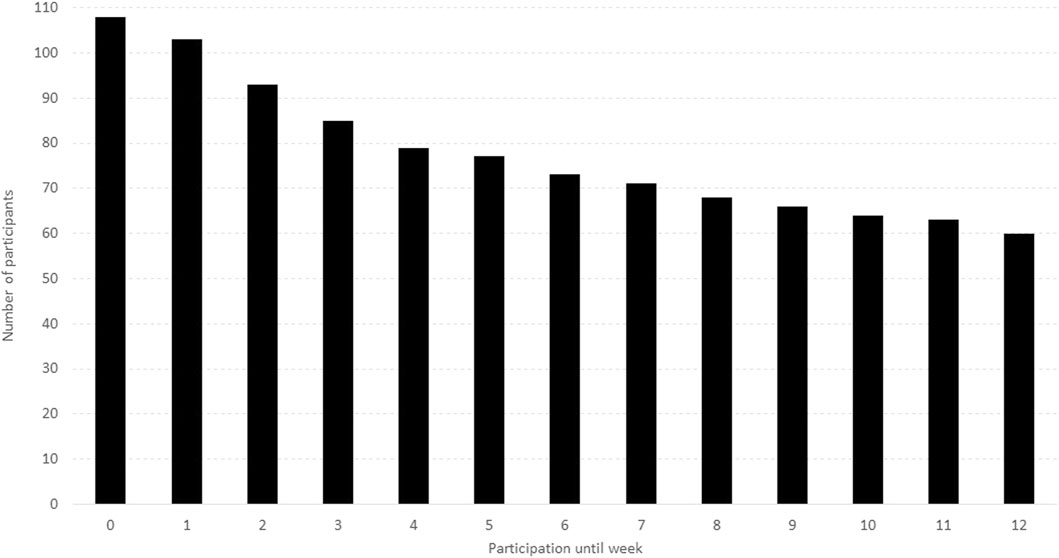

According to the app usage data, 60 participants (55.6%) used the app until week twelve (Figure 3). Of the ones who stopped earlier, 48% stopped using it within 2 weeks or even before the intervention started as five participants installed the app but did not start (“participation until week 0”).

From the 48 participants who did not complete the intervention, 36 participants (75.0%) provided some insights into why they stopped using the app. The reason most often mentioned was lack of time (9 participants) followed by too boring (5 participants), illness (4 participants) and injury, technical issues or holistic training exercises too easy (each mentioned by 3 participants).

The participants who did not complete the intervention tended to be older than the ones using the app until week twelve (71.8 years vs. 70.6 years) and more male than female participants stopped before week twelve (51.2% vs. 40.3%). Furthermore, these participants had on average a higher BMI (25.8 vs. 23.5) and the percentage of participants with a general health state of “excellent” or “very good” was lower (47.9% vs. 56.7%). Details can be found in Supplementary Appendix Section S4.3.

User Engagement

The app domain that was most often visited by the participants was weekly plan (50.7% of all visits) followed by diary (21.7%), newsletter and quiz (18.2%), progress (5.9%), help and safety (2.6%) and settings (0.9%). There was a total of 15,050 visits to the different domains of the app. Considering the duration participants used the app, this makes approximately 2.5 visits per participant per day.

On average, participants completed 104% (SD 54%) of the aerobic training sessions (it was possible to complete more sessions than those foreseen by the intervention), 88% (SD 55%) of the holistic exercise sessions, 65% (SD 25%) of the nutrition sessions, 56% (SD 32%) of the sleep sessions and 52% (SD 32%) of the mindfulness/relaxation sessions.

The sleep session completion rate was higher in group B that started with the sleep content in the first six weeks (64% vs. 49% in group A). Furthermore, group B rated the statement “I would have preferred to start with mindfulness/relaxation instead of sleep” with a mean of 3.2 (SD 1.3) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree). Similarly, the mindfulness/relaxation session completion rate was higher in group A that started with the mindfulness/relaxation content in the first six weeks (55% vs. 49% in group B) and group A rated the statement “I would have preferred to start with sleep instead of mindfulness/relaxation” with a mean of 2.9 (SD 1.5).

Overall Satisfaction

Respondents of the post-intervention questionnaire reported high overall satisfaction with the app (“Overall, I am satisfied with this app.” mean 6.0 (SD 1.0) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (fully disagree) to 7 (fully agree)) and a high likelihood of using the app again (“I would use this app again.” mean 5.7 (SD 1.5)). Furthermore, 14 of 15 interviewees would recommend the app to others and eleven would continue using the app. General aspects that were liked the most included variety of topics addressed in the intervention (4/15 interviewees), holistic approach to lifestyle (three interviewees), simple handling of the app (three interviewees), structure of the app (three interviewees) and the fact that the app structured the days and weeks (two interviewees).

Most Helpful Content

According to the interviewees, the most helpful content in the physical activity domain was the exercise videos (10/15 interviewees) including the fact that no special aids or tools were required to perform the exercises (two interviewees). Five of 15 interviewees perceived the nutrition content as educational although a lot of information was not new to them. Furthermore, five interviewees liked that the content confirmed what they already knew and perceived it as a welcomed reminder. Text (four interviewees) and podcasts (three interviewees) were considered helpful modes of delivery. Furthermore, the sleep content was perceived as important and useful due to new or insightful information provided (5/15 interviewees), or confirming their previous knowledge (four interviewees). Seven of 15 interviewees perceived the audio files that guided through the different mindfulness/relaxation techniques as being the most helpful content.

Potential for Future Development

Five of 15 interviewees did not like the voice that guided the body scan and the sitting meditation. Four interviewees considered the aerobic training instructions as not helpful because they perceived them as not specific enough or not completely clear. Technical issues related to watching the exercise videos were mentioned by four interviewees; to some extent, however, the issues were due to poor internet connectivity of the users. A larger repertoire of exercises, along with the option to access content in offline mode, was desired by two interviewees. Two participants also suggested exercise videos with more pep and drive. Eleven interviewees said there was no content where they would have preferred to have a contact person for face-to-face interaction. The interviewees were also asked if they could think about using the app while being outdoors: six interviewees said yes, five no and four were uncertain. Furthermore, the following domains were reported to contribute to their mental wellbeing and could be considered as potential additions to the app by at least two participants of the post-intervention questionnaire: creativity (music, singing, painting), cognitive training, social relationships, faith/spirituality/religion, and nature.

Achieving Intended Goals

Participants rated the statement “the app helped me to move regularly” with a mean of 5.3 (SD 1.5; 7-point Likert scale). The statement “the app helped me to eat healthy and according to my needs” achieved an average rating of 5.1 (SD 1.3). The statement “the app helped me to improve my sleep habits” was rated with a mean of 4.9 (SD 1.5) and “the app helped me to improve my mental wellbeing” achieved an average rating of 5.1 (SD 1.3).

Influence on Behaviour

Nine interviewees reported that the intervention influenced their physical activity behaviour at least partially with more mindful physical activity being most often mentioned (three interviewees). In addition, eight interviewees reported that their behaviour related to eating was influenced with more mindful eating being most often mentioned (three interviewees). Eight interviewees reported the intervention impacted their sleep behaviour with more consciousness about sleeping behaviour, not drinking coffee in the evening and being more relaxed when awaking during the night each mentioned by two interviewees. In addition, nine interviewees reported that the mindfulness/relaxation content influenced their behaviour with increased mindfulness (three interviewees) and relaxation (two interviewees) being most frequently mentioned.

App Usability

The overall app usability assessed with the MAUQ was on average rated at 5.6 (SD 0.7). From the three MAUQ subscales, ease of use was scored the highest (mean 6.0, SD 0.9), followed by interface satisfaction (mean 5.8, SD 0.7) and usefulness (mean 5.1, SD 0.9). Details can be found in Supplementary Appendix Section S4.5.

Pre-Post Comparison of Effectiveness Measures

The SF-36 mental health subscale and flourishing scale showed a statistically significant change from pre-to post-intervention whereas the change for the SF-36 vitality subscale was not statistically significant. Details can be found in Supplementary Appendix Section S4.6.

Discussion

We examined the user experience and usability of a 12-week digital MLI that has been developed involving community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and older, and incorporated four lifestyle domains (physical activity, nutrition, sleep and mindfulness/relaxation) to improve HRQoL using a mixed methods approach. One hundred eight older adults participated in the study. Fifty-six percent of participants completed the 12-week intervention that was delivered through a mobile app. Users who completed the intervention experienced it as highly satisfactory and rated the usability as high. Furthermore, user engagement was particularly high for the physical activity content.

Participant retention has been described as a common challenge of digital health interventions [65]. For web-based interventions promoting health through behavioural change, approximately 50% of the users stopped before the end of the intervention [66]. Similarly, a recent scoping review found a median completion rate of remote digital health studies of 48% [67]. The dropout rate of 44.4% in our study is at the upper end of the range of 2%–52% reported in a recent meta-analysis of web-based MLIs for brain health in older adults [19]. We tried to reduce the complexity of tasks required from the participants and included regular reminders as nudges [67]. However, our intervention did not include personal contact for participants although this aspect may increase participant retention [67]. Especially, an in-person onboarding process may would have increased participant retention [67]. Although adherence to digital interventions may be increased with human support [68], the combination of digital and human support has its own challenges [41].

To enhance user experience of future interventions and identify potential barriers, we tried to gain insights into the reasons for not completing our intervention. By targeting a low burden for the respondents, we were able to receive feedback from 75% of the participants who did not complete the intervention. Reported reasons for dropping out were comparable to the results of a recent meta-analysis and included time constraints, physical illness, technical issues and dissatisfaction with the content [19]. The average participant who dropped out of our intervention tended to be older, had a higher BMI and reported a lower general health state than the ones who completed the intervention. Consequently, we may have not been able to satisfy the needs of some older and less healthy participants. As the health state is related to health literacy and digital health literacy [69, 70], this may also indicate that health literacy and digital health literacy was lower in the participants who did not complete the intervention. Therefore, there seems to be no one-size-fits-all solution for digital MLIs even if developed in a user-centred approach.

User engagement was especially high in the physical activity domain where participants on average completed more than the number of intended aerobic training sessions and 88% of the holistic exercise sessions. This corresponds to findings from a MLI with digital elements for improving brain health, where participants prioritized content topics according to the following order (from top to bottom priority): physical activity, cognitive training, nutrition, stress management, sleep, and social engagement [63]. Consequently, physical activity seems to be a core domain of MLI for older adults. In addition, the exercise videos were perceived as the most helpful content in the physical activity domain by ten out of 15 interviewees. This may be attributed to several intervention characteristics, such as its structured multicomponent design – incorporating strength, balance and flexibility training for the whole body (lower limbs, core and upper limbs) – and its three intensity levels which allowed for personalization. Additionally, the exercises were easy to perform at home or in other settings, requiring only a chair and additional weights (e.g., water bottles), and were demonstrated by peers.

In our MLI, we specifically added the two lifestyle domains sleep and mindfulness/relaxation to the more common domains of physical activity and nutrition. Further aspects such as social relationships, risky substance abuse and cognitive training, were also covered, but less extensively. Many interviewees particularly appreciated this holistic approach and the variety of topics covered. Furthermore, these lifestyle domains are interconnected. For example, our study showed the effect of the mindfulness/relaxation domain on the physical activity and nutrition domain with more mindful physical activity and more mindful eating being most often mentioned by the interviewees regarding how the intervention influenced their behaviour. This increased awareness of a lifestyle behaviour may change the type of motivation and lead to behaviour change [71, 72]. Consequently, the stress management lifestyle domain may act as a door opener for healthy behaviour in other lifestyle domains [73]. Similarly, the sleep domain is highly interconnected with the other five lifestyle domains and sleep influences goal-directed and stimulus-driven behaviour [74]. However, the benefit of a holistic approach and a variety of topics needs to be well balanced against the time required to spend on an MLI. Although we intended to gain insights into the impact of timing and order of the two additional domains sleep and mindfulness/relaxation using a cross-over design, the user engagement data did not reveal any substantial differences between the two groups. Therefore, giving choices to the users in regard to timing and order may be an option to further increase user engagement in future digital MLIs for older adults [41].

The usability observed in our study was slightly lower compared to an app specifically developed for patients with inflammatory arthritis [75] but higher than in a study investigating an mHealth app for patients with or at risk for cardiovascular disease [76]. Our app achieved the highest usability ratings for the two statements in the MAUQ “The app was easy to use.” and “It was easy for me to learn to use the app.” This might be largely due to our very simple and minimalistic app design using high contrast colours and allowing for large font sizes (which could be tailored).

A main strength of our study is the mixed methods approach, which enabled us to complement quantitative with qualitative data. This deepened our understanding of digital MLIs for community-dwelling older adults and provided guidance for future development and implementation [41].

As a limitation, our population was more vital than the average Swiss person in the same age group [77] and showed high physical activity levels at pre-intervention. Furthermore, we did not collect information about participants’ education, socioeconomic status or digital literacy. As a further limitation, abuse of risky substances was not addressed as a single domain but covered in the sleep domain (sleeping pills, alcohol, nicotine) and nutrition domain (alcohol). In addition, we did not include social relationships as an independent single intervention domain but rather addressed social aspects, for example, group physical activity, eating together or mindfulness communication, in the other domains to highlight the interconnection between the different lifestyle domains. However, participants mentioned that social relationships could be a more prominent topic in future MLIs. This also corresponds to previous findings showing that social aspects are a facilitator for older adults to participate in MLIs [34]. Therefore, future studies may investigate the user experience and usability of blended MLI approaches for community-dwelling older adults combining digital with face-to-face intervention activities specifically enabling social contact [66].

Conclusion

This study aimed to examine the user experience and usability of a 12-week digital MLI to improve HRQoL in community-dwelling older adults aged 65 years and above using a mixed methods approach. The intervention was developed involving older adults and delivered through a mobile application focusing on physical activity, nutrition, sleep and mindfulness/relaxation. Although participant retention can be a challenge, our study shows that such a digital MLI can lead to positive user experience and high usability in community-dwelling older adults. These findings may inform the development and evaluation of future digital MLIs targeting HRQoL and mental wellbeing in older adults.

Ethics Statement

The responsible ethics committee of the Canton of Bern has decided that this study does not fall under the Swiss Human Research Act such that an ethical application was not required (BASECNr. Req-2023-00104). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants provided their informed consent digitally. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data in this article.

Author Contributions

RM: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing; MW: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, software, writing–review and editing; AR: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing–review and editing; KH: methodology, writing–review and editing; AV: methodology, writing–review and editing; K-US: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing–review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Velux Foundation (VELUX STIFTUNG). The funding body had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Generative AI Statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Peter Bruins for the technical development of the application, Bruno Perruchi for advising us on the mindfulness/relaxation content, Angelika Hayer for advising us on the nutrition content, Rachel Strahm for transcribing some of the interviews and André Meichtry for conducting the statistical analyses. We would also like to thank all older adults who contributed to the development process including the prototype testings, the particpants of this study and all institutions, organizations, and associations that supported us in the recruitment of participants.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2025.1608014/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Friedman, SM. Lifestyle (Medicine) and Healthy Aging. Clin Geriatr Med (2020) 36:645–53. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2020.06.007

2. Kyu, HH, Abate, D, Abate, KH, Abay, SM, Abbafati, C, Abbasi, N, et al. Global, Regional, and National Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for 359 Diseases and Injuries and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet (2018) 392:1859–922. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32335-3

3. Nyberg, ST, Singh-Manoux, A, Pentti, J, Madsen, IEH, Sabia, S, Alfredsson, L, et al. Association of Healthy Lifestyle with Years Lived without Major Chronic Diseases. JAMA Intern Med (2020) 180:760–8. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0618

4. Bian, Z, Wang, L, Fan, R, Sun, J, Yu, L, Xu, M, et al. Genetic Predisposition, Modifiable Lifestyles, and Their Joint Effects on Human Lifespan: Evidence from Multiple Cohort Studies. BMJ Evid-based Med (2024) 29:255–63. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2023-112583

5. Wang, J, Chen, C, Zhou, J, Ye, L, Li, Y, Xu, L, et al. Healthy Lifestyle in Late-Life, Longevity Genes, and Life Expectancy Among Older Adults: A 20-Year, Population-Based, Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Healthy Longev (2023) 4(4):e535–e543. doi:10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00140-X

6. Frates, B, Bonnet, J, Jospeh, R, and Peterson, J. Lifestyle Medicine Handbook, an Introduction to the Power of Healthy Habits. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning. 2nd ed. (2020).

7. Lippman, D, Stump, M, Veazey, E, Guimarães, ST, Rosenfeld, R, Kelly, JH, et al. Foundations of Lifestyle Medicine and its Evolution. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes (2024) 8:97–111. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.11.004

8. Strandberg, TE, Levälahti, E, Ngandu, T, Solomon, A, Kivipelto, M, Kivipelto, M, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in a Multidomain Intervention Trial to Prevent Cognitive Decline (FINGER). Eur Geriatr Med (2017) 8:164–7. doi:10.1016/j.eurger.2016.12.005

9. Kulmala, J, Ngandu, T, Havulinna, S, Levälahti, E, Lehtisalo, J, Solomon, A, et al. The Effect of Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention on Daily Functioning in Older People. J Am Geriatr Soc (2019) 67:1138–44. doi:10.1111/jgs.15837

10. Castro, CB, Costa, LM, Dias, CB, Chen, J, Hillebrandt, H, Gardener, SL, et al. Multi-Domain Interventions for Dementia Prevention - A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging (2023) 27:1271–80. doi:10.1007/s12603-023-2046-2

11. Noach, S, Witteman, B, Boss, HM, and Janse, A. Effects of Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions on Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease Prevention: A Literature Review and Future Recommendations. Cereb Circ - Cogn Behav (2023) 4:100166. doi:10.1016/j.cccb.2023.100166

12. Toman, J, Klímová, B, and Vališ, M. Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention Strategies for the Delay of Cognitive Impairment in Healthy Aging. Nutrients (2018) 10:1560. doi:10.3390/nu10101560

13. Lu, Y, Niti, M, Yap, KB, Tan, CTY, Nyunt, MSZ, Feng, L, et al. Effects of Multi-Domain Lifestyle Interventions on Sarcopenia Measures and Blood Biomarkers: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial of Community-Dwelling Pre-Frail and Frail Older Adults. Aging (2021) 13:9330–47. doi:10.18632/aging.202705

14. Marengoni, A, Rizzuto, D, Fratiglioni, L, Antikainen, R, Laatikainen, T, Lehtisalo, J, et al. The Effect of a 2-Year Intervention Consisting of Diet, Physical Exercise, Cognitive Training, and Monitoring of Vascular Risk on Chronic Morbidity—The FINGER Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc (2018) 19:355–60. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.020

15. Ory, MG, Lee, S, Han, G, Towne, SD, Quinn, C, Neher, T, et al. Effectiveness of a Lifestyle Intervention on Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Physical Activity Among Older Adults: Evaluation of Texercise Select. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15:E234. doi:10.3390/ijerph15020234

16. Wimo, A, Handels, R, Antikainen, R, Eriksdotter, M, Jönsson, L, Knapp, M, et al. Dementia Prevention: The Potential Long-Term Cost-Effectiveness of the FINGER Prevention Program. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc (2023) 19:999–1008. doi:10.1002/alz.12698

17. Fourteau, M, Virecoulon Giudici, K, Rolland, Y, Vellas, B, and de Souto Barreto, P. Associations between Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions and Intrinsic Capacity Domains during Aging: A Narrative Review. JAR Life (2020) 9:16–25. doi:10.14283/jarlife.2020.6

18. Sato, M, Betriana, F, Tanioka, R, Osaka, K, Tanioka, T, and Schoenhofer, S. Balance of Autonomic Nervous Activity, Exercise, and Sleep Status in Older Adults: A Review of the Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18:12896. doi:10.3390/ijerph182412896

19. Wesselman, LM, Hooghiemstra, AM, Schoonmade, LJ, de Wit, MC, van der Flier, WM, and Sikkes, SA. Web-Based Multidomain Lifestyle Programs for Brain Health: Comprehensive Overview and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Ment Health (2019) 6:e12104. doi:10.2196/12104

20. Canever, JB, Zurman, G, Vogel, F, Sutil, DV, Diz, JBM, Danielewicz, AL, et al. Worldwide Prevalence of Sleep Problems in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med (2024) 119:118–34. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2024.03.040

21. Qin, S, and Chee, MWL. The Emerging Importance of Sleep Regularity on Cardiovascular Health and Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: A Review of the Literature. Nat Sci Sleep (2024) 16:585–97. doi:10.2147/NSS.S452033

22. Öberg, S, Sandlund, C, Westerlind, B, Finkel, D, and Johansson, L. The Existing State of Knowledge about Sleep Health in Community-Dwelling Older Persons – A Scoping Review. Ann Med (2024) 56:2353377. doi:10.1080/07853890.2024.2353377

23. Sella, E, Toffalini, E, Canini, L, and Borella, E. Non-Pharmacological Interventions Targeting Sleep Quality in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Ment Health (2023) 27:847–61. doi:10.1080/13607863.2022.2056879

24. Gupta, CC, Irwin, C, Vincent, GE, and Khalesi, S. The Relationship between Diet and Sleep in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Curr Nutr Rep (2021) 10:166–78. doi:10.1007/s13668-021-00362-4

25. Seo, S, and Mattos, MK. The Relationship between Social Support and Sleep Quality in Older Adults: A Review of the Evidence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr (2024) 117:105179. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2023.105179

26. González-Martín, AM, Aibar-Almazán, A, Rivas-Campo, Y, Marín-Gutiérrez, A, and Castellote-Caballero, Y. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Older Adults with Sleep Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Public Health (2023) 11:1242868. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1242868

27. Lannon-Boran, C, Hannigan, C, Power, JM, Lambert, J, and Kelly, M. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention on Cognitively Unimpaired Older Adults’ Cognitive Function and Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Ment Health (2024) 28:23–35. doi:10.1080/13607863.2023.2228255

28. Whitfield, T, Barnhofer, T, Acabchuk, R, Cohen, A, Lee, M, Schlosser, M, et al. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Programs on Cognitive Function in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol Rev (2022) 32:677–702. doi:10.1007/s11065-021-09519-y

29. Talebisiavashani, F, and Mohammadi-Sartang, M. The Effect of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Mental Health and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Aging Health (2024):08982643241263882. doi:10.1177/08982643241263882

30. Hazlett-Stevens, H, Singer, J, and Chong, A. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy with Older Adults: A Qualitative Review of Randomized Controlled Outcome Research. Clin Gerontol (2019) 42:347–58. doi:10.1080/07317115.2018.1518282

31. Hmwe, NTT, Chan, CM, and Shayamalie, TGN. Older People’s Experiences of Participation in Mindfulness-Based Intervention Programmes: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Int J Ment Health Nurs (2024) 33:1272–88. doi:10.1111/inm.13350

32. Bott, NT, Hall, A, Madero, EN, Glenn, JM, Fuseya, N, Gills, JL, et al. Face-to-Face and Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions to Enhance Cognitive Reserve and Reduce Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias: A Review of Completed and Prospective Studies. Nutrients (2019) 11:2258. doi:10.3390/nu11092258

33. Singh, B, Ahmed, M, Staiano, AE, Gough, C, Petersen, J, Vandelanotte, C, et al. A Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta-Meta-Analysis of eHealth and mHealth Interventions for Improving Lifestyle Behaviours. NPJ Digit Med (2024) 7:179. doi:10.1038/s41746-024-01172-y

34. van der Laag, PJ, Dorhout, BG, Heeren, AA, Veenhof, C, Barten, D-JJA, and Schoonhoven, L. Barriers and Facilitators for Implementation of a Combined Lifestyle Intervention in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Front Public Health (2023) 11:1253267. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1253267

35. Castro, R, Ribeiro-Alves, M, Oliveira, C, Romero, CP, Perazzo, H, Simjanoski, M, et al. What Are We Measuring when We Evaluate Digital Interventions for Improving Lifestyle? A Scoping Meta-Review. Front Public Health (2021) 9:735624. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.735624

36. World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med (1995) 41:1403–9. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K

37. Huppert, FA. Psychological Well-Being: Evidence Regarding its Causes and Consequences. Appl Psychol Health Well-being (2009) 1:137–64. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01008.x

38. Przybylko, G, Morton, D, Kent, L, Morton, J, Hinze, J, Beamish, P, et al. The Effectiveness of an Online Interdisciplinary Intervention for Mental Health Promotion: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychol (2021) 9:77. doi:10.1186/s40359-021-00577-8

39. Boucher, E, Honomichl, R, Ward, H, Powell, T, Stoeckl, SE, and Parks, A. The Effects of a Digital Well-Being Intervention on Older Adults: Retrospective Analysis of Real-World User Data. JMIR Aging (2022) 5:e39851. doi:10.2196/39851

40. Johnson, RB, Onwuegbuzie, AJ, and Turner, LA. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J Mix Methods Res (2007) 1:112–33. doi:10.1177/1558689806298224

41. Yardley, L, Spring, BJ, Riper, H, Morrison, LG, Crane, DH, Curtis, K, et al. Understanding and Promoting Effective Engagement with Digital Behavior Change Interventions. Am J Prev Med (2016) 51:833–42. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.015

43. Grossman, P, Niemann, L, Schmidt, S, and Walach, H. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Health Benefits: A Meta-Analysis. J Psychosom Res (2004) 57:35–43. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

44. Muhammad Khir, S, Wan Mohd Yunus, WMA, Mahmud, N, Wang, R, Panatik, SA, Mohd Sukor, MS, et al. Efficacy of Progressive Muscle Relaxation in Adults for Stress, Anxiety, and Depression: A Systematic Review. Psychol Res Behav Manag (2024) 17:345–65. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S437277

45. Gemert-Pijnen, JEvan, Nijland, N, Limburg, M, Ossebaard, HC, Kelders, SM, Eysenbach, G, et al. A Holistic Framework to Improve the Uptake and Impact of eHealth Technologies. J Med Internet Res (2011) 13:e1672. doi:10.2196/jmir.1672

46. Wesselman, LMP, Schild, A-K, Coll-Padros, N, van der Borg, WE, Meurs, JHP, Hooghiemstra, AM, et al. Wishes and Preferences for an Online Lifestyle Program for Brain Health—A Mixed Methods Study. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv (2018) 4:141–9. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.003

47. Vaughn, LM, and Jacquez, F. Participatory Research Methods – Choice Points in the Research Process. J Particip Res Methods (2020) 1. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.35844/001c.13244

48. Leask, CF, Sandlund, M, Skelton, DA, Altenburg, TM, Cardon, G, Chinapaw, MJM, et al. Framework, Principles and Recommendations for Utilising Participatory Methodologies in the Co-Creation and Evaluation of Public Health Interventions. Res Involv Engagem (2019) 5:2. doi:10.1186/s40900-018-0136-9

49. Michie, S, Richardson, M, Johnston, M, Abraham, C, Francis, J, Hardeman, W, et al. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (V1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann Behav Med (2013) 46:81–95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

50. Weber, M, Schmitt, K-U, Frei, A, Puhan, MA, and Raab, AM. Needs Assessment in Community-Dwelling Older Adults toward Digital Interventions to Promote Physical Activity: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Digit Health (2023) 9:20552076231203785. doi:10.1177/20552076231203785

51. Ware, JE, and Sherbourne, CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Med Care (1992) 30:473–83.

52. Boxer, H, and Snyder, S. Five Communication Strategies to Promote Self-Management of Chronic Illness. Fam Pract Manag (2009) 16:12–6.

53. EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a New Facility for the Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life. Health Policy (1990) 16:199–208. doi:10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9

54. Zhou, L, Bao, J, Setiawan, IMA, Saptono, A, and Parmanto, B. The mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (MAUQ): Development and Validation Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth (2019) 7:e11500. doi:10.2196/11500

55. Kopka, M, Slagman, A, Schorr, C, Krampe, H, Altendorf, M, Balzer, F, et al. German mHealth App Usability Questionnaire (G-MAUQ) and Short Version (G-MAUQ-S): Translation and Validation Study. Smart Health (2024) 34:100517. doi:10.1016/j.smhl.2024.100517

56. Braun, V, and Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psychol (2006) 3:77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

57. Ivankova, NV, Creswell, JW, and Stick, SL. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods (2006) 18:3–20. doi:10.1177/1525822X05282260

58. Johnson, RE, Grove, AL, and Clarke, A. Pillar Integration Process: A Joint Display Technique to Integrate Data in Mixed Methods Research. J Mix Methods Res (2019) 13:301–20. doi:10.1177/1558689817743108

59. Diener, E, Wirtz, D, Tov, W, Kim-Prieto, C, Choi, D, Oishi, S, et al. New Well-Being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Soc Indic Res (2010) 97:143–56. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

60. Haywood, KL, Garratt, AM, and Fitzpatrick, R. Quality of Life in Older People: A Structured Review of Generic Self-Assessed Health Instruments. Qual Life Res (2005) 14:1651–68. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-1743-0

61. Renfrew, ME, Morton, DP, Morton, JK, Hinze, JS, Beamish, PJ, Przybylko, G, et al. A Web- and Mobile App–Based Mental Health Promotion Intervention Comparing Email, Short Message Service, and Videoconferencing Support for a Healthy Cohort: Randomized Comparative Study. J Med Internet Res (2020) 22:e15592. doi:10.2196/15592

62. Caprara, M, Fernández-Ballesteros, R, and Alessandri, G. Promoting Aging Well: Evaluation of Vital-Aging-Multimedia Program in Madrid, Spain. Health Promot Int (2016) 31:515–22. doi:10.1093/heapro/dav014

63. Norton, MC, Clark, CJ, Tschanz, JT, Hartin, P, Fauth, EB, Gast, JA, et al. The Design and Progress of a Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention to Improve Brain Health in Middle-Aged Persons to Reduce Later Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: The Gray Matters Randomized Trial. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv (2015) 1:53–62. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2015.05.001

64. Lara, J, O’Brien, N, Godfrey, A, Heaven, B, Evans, EH, Lloyd, S, et al. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Intervention to Promote Healthy Eating, Physical Activity and Meaningful Social Connections Compared with Usual Care Control in People of Retirement Age Recruited from Workplaces. PLOS ONE (2016) 11:e0159703. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159703

66. Kelders, SM, Kok, RN, Ossebaard, HC, and Gemert-Pijnen, JEV. Persuasive System Design Does Matter: A Systematic Review of Adherence to Web-Based Interventions. J Med Internet Res (2012) 14:e152. doi:10.2196/jmir.2104

67. Daniore, P, Nittas, V, and Wyl, V. Enrollment and Retention of Participants in Remote Digital Health Studies: Scoping Review and Framework Proposal. J Med Internet Res (2022) 24:e39910. doi:10.2196/39910

68. Mohr, DC, Cuijpers, P, and Lehman, K. Supportive Accountability: A Model for Providing Human Support to Enhance Adherence to eHealth Interventions. J Med Internet Res (2011) 13:e30. doi:10.2196/jmir.1602

69. Berkman, ND, Sheridan, SL, Donahue, KE, Halpern, DJ, and Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med (2011) 155:97–107. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

70. Arias, L, M del, P, Ong, BA, Borrat Frigola, X, Fernández, AL, Hicklent, RS, et al. Digital Literacy as a New Determinant of Health: A Scoping Review. PLOS Digit Health (2023) 2:e0000279. doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000279

71. Ludwig, VU, Brown, KW, and Brewer, JA. Self-Regulation without Force: Can Awareness Leverage Reward to Drive Behavior Change? Perspect Psychol Sci (2020) 15:1382–99. doi:10.1177/1745691620931460

72. Michaelsen, MM, and Esch, T. Understanding Health Behavior Change by Motivation and Reward Mechanisms: A Review of the Literature. Front Behav Neurosci (2023) 17:1151918. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1151918

73. Shurney, D. Employing Mindfulness in Lifestyle Medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med (2019) 13:561–4. doi:10.1177/1559827619867625

74. Chen, J, Liang, J, Lin, X, Zhang, Y, Zhang, Y, Lu, L, et al. Sleep Deprivation Promotes Habitual Control over Goal-Directed Control: Behavioral and Neuroimaging Evidence. J Neurosci (2017) 37:11979–92. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1612-17.2017

75. Fedkov, D, Berghofen, A, Weiss, C, Peine, C, Lang, F, Knitza, J, et al. Efficacy and Safety of a Mobile App Intervention in Patients with Inflammatory Arthritis: A Prospective Pilot Study. Rheumatol Int (2022) 42:2177–90. doi:10.1007/s00296-022-05175-4

76. Reimer, LM, Nissen, L, von Scheidt, M, Perl, B, Wiehler, J, Najem, SA, et al. User-Centered Development of an mHealth App for Cardiovascular Prevention. Digit Health (2024) 10:20552076241249269. doi:10.1177/20552076241249269

Keywords: physical activity, nutrition, sleep, mindfulness, relaxation, lifestyle medicine, health-related quality of life, mHealth

Citation: Mattli R, Weber M, Raab AM, Haas K, Vorster A and Schmitt K-U (2025) Digital Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention for Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Mixed Methods Evaluation. Int. J. Public Health 70:1608014. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2025.1608014

Received: 04 October 2024; Accepted: 03 March 2025;

Published: 14 March 2025.

Edited by:

Martin Röösli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Maddalena Fiordelli, University of Italian Switzerland, SwitzerlandVictoria Leclercq, Sciensano, Belgium

Copyright © 2025 Mattli, Weber, Raab, Haas, Vorster and Schmitt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Renato Mattli, cmVuYXRvLm1hdHRsaUBiZmguY2g=

Renato Mattli

Renato Mattli Manuel Weber

Manuel Weber Anja Maria Raab1,3

Anja Maria Raab1,3