Abstract

Objective:

To develop a machine learning (ML) model utilizing transfer learning (TL) techniques to predict hypertension in children and adolescents across South America.

Methods:

Data from two cohorts (children and adolescents) in seven South American cities were analyzed. A TL strategy was implemented by transferring knowledge from a CatBoost model trained on the children’s sample and adapting it to the adolescent sample. Model performance was evaluated using standard metrics.

Results:

Among children, the prevalence of normal blood pressure was 88.9% (301 participants), while 14.1% (50 participants) had elevated blood pressure (EBP). In the adolescent group, the prevalence of normal blood pressure was 92.5% (284 participants), with 7.5% (23 participants) presenting with EBP. Random Forest, XGBoost, and LightGBM achieved high accuracy (0.90) for children, with XGBoost and LightGBM demonstrating superior recall (0.50) and AUC-ROC (0.74). For adolescents, models without TL showed poor performance, with accuracy and recall values remaining low and AUC-ROC ranging from 0.46 to 0.56. After applying TL, model performance improved significantly, with CatBoost achieving an AUC-ROC of 0.82, accuracy of 1.0, and recall of 0.18.

Conclusion:

Soft drinks, filled cookies, and chips were key dietary predictors of elevated blood pressure, with higher intake in adolescents. Machine learning with transfer learning effectively identified these risks, emphasizing the need for early dietary interventions to prevent hypertension and support cardiovascular health in pediatric populations.

Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) is a prevalent medical condition, affecting approximately one in four individuals worldwide, and represents a significant risk factor for heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, and mortality [1]. It is the leading global cause of morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular diseases (CVD). The complexity of HTN lies not only in its widespread prevalence but also in its asymptomatic progression during early stages, often delaying timely diagnosis and treatment [2].

The global burden of hypertension has increased significantly over recent decades, rising from 594 million cases in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015, with the majority of this growth occurring in low- and middle-income countries. This rise is primarily attributed to aging populations, lifestyle modifications, and demographic expansion. Approximately 13% of all deaths globally are associated with hypertension, underscoring its role as a major public health challenge that affects all sectors of society [3, 4].

Evidence from pathophysiological and epidemiological studies highlights the association between hypertension during childhood and an increased risk of hypertension and adverse cardiovascular events in adulthood. However, identifying HTN in pediatric populations poses unique challenges due to the dynamic changes in growth and development that complicate standardization of definitions and measurements, as well as the assessment of cardiovascular outcomes in children compared to adults [5, 6].

Data on the prevalence of elevated blood pressure in children are often derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and are frequently limited to a single blood pressure measurement session [7, 8]. Since 1988, research has documented a rising prevalence of elevated blood pressure in children, including both hypertension and prehypertension, with rates consistently higher among boys (15%–19%) compared to girls (7%–12%). Preventive strategies targeting individuals and high-risk groups are essential to mitigate the long-term consequences of HTN. The necessity for early identification of at-risk individuals has spurred increasing interest in predictive models for hypertension risk [9, 10].

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool in healthcare, demonstrating its utility in managing a variety of clinical conditions [11, 12]. AI facilitates the development of accurate risk prediction models for HTN by integrating traditional cardiovascular risk factors with multi-omic, socioeconomic, behavioral, and environmental data, thereby enabling the formulation of personalized treatment approaches [13].

A promising innovation within the domain of AI is transfer learning (TL), a machine learning (ML) technique that repurposes models trained for one task as a foundation for related tasks. TL is particularly advantageous in scenarios where the target dataset is limited, a common challenge in pediatric health research. For instance, TL has been successfully employed in studies predicting diabetes and cardiovascular diseases by leveraging large datasets to enhance predictive accuracy in smaller, specific populations [14]. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of TL in predicting glucose levels among patients with type 1 diabetes, where it substantially improved model performance despite limited data availability. In the context of HTN, TL has the potential to transfer knowledge from models trained on extensive adult datasets to pediatric populations, thereby addressing the scarcity of data in children and adolescents [15, 16].

Given the increasing prevalence of elevated blood pressure in the pediatric population and its significant long-term health implications, this study aims to develop a machine learning model employing transfer learning to predict hypertension in children and adolescents in South America. By leveraging data from a comprehensive pediatric database, this study seeks to improve the accuracy of predictions and facilitate early interventions in these populations.

Methods

Study Design

This study utilized data from the “South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE)” Study, an observational, cross-sectional epidemiological investigation conducted across seven South American cities: Buenos Aires (Argentina), Lima (Peru), Medellín (Colombia), Montevideo (Uruguay), Santiago (Chile), São Paulo (Brazil), and Teresina (Brazil) in the academic year 2015 and 2016. These cities were selected based on their hosting of specialized research centers and their populations exceeding 500,000 inhabitants (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) Study (2015/2016) research centers by country. *SAYCARE Study, South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental Study held in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Lima (Peru), Medellin (Colombia), Montevideo (Uruguay), Santiago (Chile), and São Paulo and Teresina (Brazil).

Study Population

The general study population consisted of 1,067 children (aged 3–10 years) and 495 adolescents (aged 11–18 years), enrolled in educational institutions ranging from preschool to the third year of high school, encompassing both public and private schools across the participating cities. From this overall cohort, 351 children and 307 adolescents were selected specifically for the hypertension prediction analyses. The sample size was determined based on prior experience with multicentric projects and insights gained from foundational studies, including the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence Cross-Sectional Study (HELENA-CSS) and the IDEFICS (Identification and Prevention of Dietary- and Lifestyle-Induced Health Effects in Children and Infants) Study [17, 18]. Additionally, a feasibility pilot study was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the employed methods, ensuring robust methodological underpinnings. This research aims to address critical knowledge gaps in the health of children and adolescents, thereby providing a solid evidence base for future health interventions and policy initiatives targeting these populations [19].

Blood Pressure Measurement

Blood pressure was measured using the Omron HEM-7200, a validated digital oscillometric device for pediatric populations [20]. Calibration involved activating the inflation mechanism and was performed for all devices used during the study. Measurements were taken on the right arm to account for potential aortic coarctation, with the arm positioned at heart level. Participants sat in a quiet setting with their backs supported, one arm resting on a flat surface, and feet uncrossed and flat on the floor. After a 5-min rest, blood pressure was measured following protocols from the American Heart Association and British Hypertension Society [21]. Two readings were taken 2 min apart; a third measurement was conducted if the difference between readings exceeded 5 mmHg. Elevated blood pressure was defined as systolic or diastolic readings above the 95th percentile for sex, age, and height, per American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines. Sensitivity and specificity analyses assessed the accuracy of the Omron HEM-7200 compared to mercury column readings [22].

Data Preprocessing

Missing Data Imputation and Preprocessing

The treatment of missing data prioritized dataset integrity and minimization of bias, following a structured and systematic approach. Initially, variables not selected for inclusion in the study were discarded. Next, missing values were identified, and their prevalence was quantified for each variable.

Records with missing values in critical variables (i.e., those with more than 30% missing data) were removed to prevent significant analytical bias. For variables with less than 30% missing values, imputation was performed using the median for numerical variables and the mode for categorical variables, ensuring that essential information was retained while maintaining dataset consistency.

To further enhance data quality and model performance, highly correlated variables (correlation coefficient >0.90) were eliminated to mitigate multicollinearity issues. The final dataset underwent rigorous validation to confirm its suitability for subsequent predictive modeling tasks.

This approach, grounded in established best practices, ensured a robust, reliable, and analytically sound dataset while minimizing unnecessary data loss or distortion.

Predictors Variables

The variable selection process was guided by evidence from previous studies, a comprehensive literature review, and consultations with subject matter experts [23, 24]. The predictors were measured using reliable and validated questionnaires tailored to the age group, derived from the SAYCARE Study [20, 25–31], whose instruments underwent rigorous validation and adaptation processes to ensure their accuracy and suitability.

A total of 28 variables were incorporated into the predictive model including sociodemographic [biological sex, age], socioeconomic factors [household income (monthly family income based on the minimum wage) and maternal education (< high school, high school, technical education, ≥ university degree)], environmental [sex, age, place of residence, the specific location of the school and questions about the social environment and infrastructure of the residential area], and energy balance behaviors [dietary intake patterns (food items usual consumption), daily physical activity level (moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during physical education classes, leisure time, and transportation), sleep duration (average hours total night sleep time), and daily screen time (spends in front of a television or computer or playing video games)] and waist circumference (cm). The entire description of the predictors is in the Supplementary Material S1, S2.

Ethical Considerations

The study followed strict ethical guidelines to ensure participant safety and informed consent. A formal request detailing the study’s objectives and methodology was presented to school administrations, allowing them to consent to participate in the project. For the schools that agreed, potential participants and their parents or guardians received an information letter and a verbal explanation. Informed consent was obtained through the signed Informed Consent Form (ICF) by parents or guardians, and participants provided their signatures on an Assent Form when required. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo (FMUSP) under research protocol no 232/14, as well as by the respective research ethics committees of all participating centers.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The machine learning methods used in this study included Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, chosen for their robustness, ability to handle heterogeneous data, and high effectiveness in modeling nonlinear relationships. The analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.6.5), with the support of libraries such as scikit-learn and SHAP for interpretability analysis.

To evaluate the model’s performance, we employed metrics such as accuracy, recall, F1 score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC), with AUC-ROC serving as the primary criterion for selecting the final model, complemented by consistent results in other metrics. A 5-fold cross-validation was performed to ensure that the models were tested on different data subsets, reducing the risk of overfitting.

Hyperparameter optimization was carried out using the GridSearchCV function, enabling a systematic search for the best parameter combinations to maximize performance. This methodological approach ensured the robustness and reliability of the predictive models, contributing to an accurate and consistent analysis of hypertension in the pediatric population.

Model Development and Performance

The study population was randomly divided into training and test sets, comprising 70% and 30% of the total sample, respectively. Hyperparameter tuning was performed to enhance model performance, with the GridSearchCV function from the scikit-learn package utilized to identify the optimal hyperparameters.

A 5-fold cross-validation was employed during training to evaluate the model’s performance and mitigate the risk of overfitting. The final assessment of model performance was conducted exclusively on the test set. Feature importance rankings were calculated based on the differences in the approaches used by each model.

Four widely recognized algorithms for supervised predictive analysis were employed in this study: Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost. Model performance was evaluated using standard predictive metrics, including accuracy, recall, F1 score, and the AUC-ROC. Model selection prioritized the algorithm with the highest AUC, alongside consistent performance across the other metrics.

Class Imbalance

To address class imbalance in the training dataset, an oversampling strategy was employed. An initial assessment of the class distribution revealed a significant discrepancy between the majority class (class 0: non-hypertensive) and the minority class (class 1: hypertensive). To mitigate this issue, the RandomOverSampler function was used to apply an oversampling technique, setting the oversampling ratio to 1. This process resulted in an equal number of samples for both classes. This approach was essential to ensure balanced representation of both classes during model training, thereby improving the performance and reliability of the predictive models for hypertension.

Transfer Learning

Transfer Learning (TL) is a machine learning approach that leverages knowledge gained in a specific domain or task and applies it to another, related domain or task. This technique has been widely utilized in various fields, including image recognition and classification, to improve model performance and efficiency when data in the target domain is limited or less informative [32, 33].

In this study, TL was employed to enhance the performance of machine learning models in the early detection of hypertension in pediatric populations, specifically children and adolescents. The TL technique used involves decision tree-based algorithms, where the trees learned from an initial model (e.g., predicting hypertension in children) are transferred to a similar algorithm applied to a different, less robust dataset (e.g., adolescents). This incremental learning process improves model performance on the adolescent sample, which would otherwise yield suboptimal results if trained exclusively on its own data.

Initially, the sample of children was used as the source domain for pre-training the models due to its more consistent and complete feature set, which provided a strong foundation for model training. The knowledge acquired during this phase was then transferred to the adolescent sample, enabling the models to adapt effectively to the nuances of this population. This approach was particularly advantageous, as the adolescent sample exhibited greater variability and a smaller volume of relevant data, making it an ideal target domain for TL. By utilizing this methodology, the study optimized the use of available data, ensuring improved model performance and a more accurate identification of hypertension across distinct age groups [34, 35].

Model Explanation and Individual Analysis

The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method provides an interpretable approach to understanding machine learning (ML) models. This model-agnostic technique evaluates the local contribution of each variable while offering a global perspective on model performance, including metrics such as accuracy, relevance, and local consistency. In this study, the SHAP algorithm was employed to investigate the contribution and importance of individual features and to analyze the nonlinear interactions between risk predictors [36].

Results

Table 1 summarizes the demographic, metabolic, and dietary characteristics of the children and adolescents included in the study. Most participants attended public schools, with a balanced distribution of sexes in both age groups. Children and adolescents showed differences in mean age and waist circumference, with adolescents displaying greater variability. Dietary habits varied widely, particularly for items such as soft drinks, filled cookies, and chips, reflecting diverse consumption patterns. Adolescents generally reported higher intake of most food items than children, potentially due to differing dietary preferences or caloric needs.

TABLE 1

| Feature | Children | Adolescents |

|---|---|---|

| Sex [n (%)] | ||

| Female | 246 (52.6) | 157 (51.1) |

| Male | 222 (47.4) | 150 (48.9) |

| School [n (%)] | ||

| Public | 265 (56.6) | 176 (57.3) |

| Private | 203 (43.4) | 131 (42.7) |

| Family Income [n (%)] | ||

| 1 Minimum Wage | 6 (6.7) | 18 (11.8) |

| 1 to 2 Minimum Wage | 12 (13.3) | 36 (23.7) |

| 2 to 5 Minimum Wage | 12 (13.3) | 37 (24.3) |

| 5 to 10 Minimum Wage | 14 (15.6) | 17 (11.2) |

| 10 to 15 Minimum Wage | 9 (10.0) | 10 (6.6) |

| 15 to 20 Minimum Wage | 6 (6.7) | 6 (3.9) |

| 20 to 25 Minimum Wage | 5 (5.6) | 2 (1.3) |

| More than 25 Minimum Wage | 7 (7.8) | 6 (4.0) |

| Don’t know/Will not inform | 19 (21.1) | 20 (13.2) |

| Maternal Education Level [n (%)] | ||

| Lower education | 7 (7.3) | 16 (10.1) |

| Lower secondary education | 11 (11.4) | 11 (7.0) |

| Higher secondary education | 17 (17.7) | 47 (29.7) |

| University degree | 50 (52.1) | 61 (38.6) |

| Technical education | 11 (11.4) | 21 (13.3) |

| Without education | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) |

| Availability of fruits and vegetables at home [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 168 (58.1) | 109 (53.2) |

| Almost always | 85 (29.4) | 57 (27.8) |

| Sometimes | 26 (9.0) | 29 (14.1) |

| Rarely | 8 (2.8) | 7 (3.4) |

| Never | 2 (0.7) | 3 (1.5) |

| Availability of dairy products at home [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 194 (68.6) | 120 (60.0) |

| Almost always | 51 (18.0) | 47 (23.5) |

| Sometimes | 21 (7.4) | 23 (11.5) |

| Rarely | 13 (4.6) | 5 (2.5) |

| Never | 4 (1.4) | 5 (2.5) |

| Availability of breads/cereals at home [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 157 (55.5) | 94 (47.7) |

| Almost always | 69 (24.4) | 57 (28.9) |

| Sometimes | 38 (13.4) | 35 (17.8) |

| Rarely | 12 (4.2) | 9 (4.6) |

| Never | 7 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) |

| Adequacy of sweets/snacks consumption [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 7 (2.5) | 14 (7.2) |

| Almost always | 7 (2.5) | 19 (9.7) |

| Sometimes | 88 (31.7) | 62 (31.8) |

| Rarely | 90 (32.4) | 63 (32.3) |

| Never | 86 (30.9) | 37 (19.0) |

| Availability of sweets/snacks at home [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 12 (4.3) | 16 (8.4) |

| Almost always | 27 (9.6) | 28 (14.7) |

| Sometimes | 72 (25.5) | 58 (30.4) |

| Rarely | 99 (35.1) | 59 (30.9) |

| Never | 72 (25.5) | 30 (15.7) |

| Permission to watch TV during meals [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 26 (9.2) | 69 (34.3) |

| Almost always | 32 (11.3) | 39 (19.4) |

| Sometimes | 101 (35.8) | 47 (23.4) |

| Rarely | 58 (20.6) | 19 (9.5) |

| Never | 65 (23.0) | 27 (13.4) |

| Consumption of fruits/vegetables as a snack without asking permission [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 122 (43.4) | 127 (64.5) |

| Almost always | 49 (17.4) | 34 (17.2) |

| Sometimes | 47 (16.7) | 13 (6.6) |

| Rarely | 39 (13.9) | 9 (4.6) |

| Never | 24 (8.5) | 14 (7.1) |

| Consumption of breads/cereals as a snack without asking permission [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 71 (25.5) | 110 (55.8) |

| Almost always | 32 (11.5) | 36 (18.3) |

| Sometimes | 58 (20.9) | 17 (8.6) |

| Rarely | 46 (16.6) | 15 (7.6) |

| Never | 71 (25.5) | 19 (9.7) |

| Snacks or sweets as a reward or consolation [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 6 (2.1) | 8 (4.0) |

| Almost always | 5 (1.8) | 4 (2.0) |

| Sometimes | 52 (18.2) | 22 (11.1) |

| Rarely | 67 (23.5) | 35 (17.7) |

| Never | 155 (54.4) | 129 (65.2) |

| Strict food rules [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 85 (30.2) | 21 (10.7) |

| Almost always | 75 (26.7) | 16 (8.2) |

| Sometimes | 68 (24.2) | 37 (18.9) |

| Rarely | 28 (10.0) | 35 (17.8) |

| Never | 25 (8.9) | 87 (44.4) |

| Parents' consumption of sweets/snacks in front of children/adolescents [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 51 (18.3) | 29 (14.9) |

| Almost always | 33 (11.9) | 21 (10.8) |

| Sometimes | 71 (25.5) | 53 (27.3) |

| Rarely | 49 (17.6) | 46 (23.7) |

| Never | 33 (11.9) | 45 (23.2) |

| Satisfaction with snack consumption habits [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 81 (29.2) | 60 (30.9) |

| Almost always | 70 (25.3) | 42 (21.7) |

| Sometimes | 64 (23.1) | 51 (26.3) |

| Rarely | 35 (12.6) | 21 (10.8) |

| Never | 27 (9.7) | 20 (10.3) |

| Pleasant mealtime moments [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 171 (60.9) | 90 (46.1) |

| Almost always | 83 (29.5) | 57 (29.2) |

| Sometimes | 20 (7.1) | 38 (19.5) |

| Rarely | 5 (1.8) | 5 (2.6) |

| Never | 2 (0.7) | 5 (2.6) |

| Parent-child relationship [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 242 (86.1) | 82 (44.8) |

| Almost always | 32 (11.4) | 47 (25.7) |

| Sometimes | 6 (2.1) | 34 (18.6) |

| Rarely | 0 (0.0) | 14 (7.7) |

| Never | 1 (0.4) | 6 (3.3) |

| Happiness at home [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 231 (83.7) | 124 (63.3) |

| Almost always | 32 (11.6) | 37 (18.9) |

| Sometimes | 7 (2.5) | 25 (12.8) |

| Rarely | 2 (0.7) | 5 (2.5) |

| Never | 4 (1.5) | 5 (2.5) |

| Arguments at home in front of the child/adolescent [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 5 (1.8) | 10 (5.1) |

| Almost always | 6 (2.2) | 20 (10.2) |

| Sometimes | 67 (24.3) | 44 (22.3) |

| Rarely | 112 (40.6) | 38 (19.2) |

| Never | 86 (31.1) | 38 (19.2) |

| Overprotection of the child/adolescent [n (%)] | ||

| Always | 56 (20.0) | 65 (32.8) |

| Almost always | 31 (11.1) | 17 (8.6) |

| Sometimes | 86 (30.7) | 40 (20.2) |

| Rarely | 62 (22.1) | 38 (19.2) |

| Never | 45 (16.1) | 38 (19.2) |

| Screen time [n (%)] | ||

| <2 h/day | 38 (23.5) | 53 (20.6) |

| >2 h/day | 124 (76.5) | 204 (79.4) |

| High Blood Pressure [n (%)] | 14.1 (50.0) | 7.5 (23.0) |

| Age (mean [±std)] | 6.9 (2.3) | 14.7 (2.1) |

| Mean waist circumference [mean (±std)] | 59.0 (9.9) | 73.5 (9.2) |

| Sleep duration [mean (±std)] | 9.2 (0.9) | 8.1 (1.6) |

| Total Physical Activity [mean (±std)] | 65.2 (105.9) | 41.9 (48.2) |

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding [mean (±std)] | 7.9 (11.7) | 13.6 (20.4) |

| Daily fruits consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 08.7 (321.1) | 203.4 (388.9) |

| Daily vegetables consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 58.5 (237.6) | 56.6 (130.5) |

| Daily crackers consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 20.8 (72.9) | 30.0 (71.7) |

| Daily cookies consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 12.7 (51.5) | 20.9 (66.1) |

| Daily filled cookie consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 14.5 (71.6) | 42.2 (126.9) |

| Daily baked goods consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 13.0 (89.1) | 23.1 (85.9) |

| Daily pizza consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 6.4 (17.7) | 26.2 (108.9) |

| Daily hamburger consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 5.5 (14.0) | 19.2 (47.9) |

| Daily breaded meat consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 14.0 (86.1) | 40.3 (163.0) |

| Daily sausage consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 8.8 (59.2) | 11.79 (34.9) |

| Daily cold meat consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 5.9 (27.0) | 12.5 (37.6) |

| Daily fish consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 7.9 (21.5) | 18.6 (84.3) |

| Daily soft drink consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 52.2 (155.0) | 128.7 (241.3) |

| Daily chips consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 5.8 (27.4) | 8.8 (34.5) |

| Daily mayonnaise consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 4.1 (15.4) | 8.3 (23.8) |

| Daily sauces consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 3.7 (9.9) | 7.8 (17.4) |

| Daily finger foods consumption in grams [mean (±std)] | 1.8 (8.4) | 8.2 (55.9) |

Descriptive statistics of the features included in the predictive model, categorized by age group, South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) Study (2015/2016).

Table 2 compares the performance of different machine learning models for diagnosing hypertension in children and adolescents. For children, all models achieved accuracies close to 90% before the application of transfer learning (TL). The Random Forest model demonstrated the highest precision (0.83), while XGBoost and LightGBM showed slightly lower values (around 0.72). In terms of recall, XGBoost and LightGBM performed best, with values of 0.50, followed by Random Forest and CatBoost, both at 0.31. The models exhibited comparable AUC-ROC, ranging between 0.71 and 0.74.

TABLE 2

| Children | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | AUC(ROC) | |

| Random Forest | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.71 | |

| XGBoost | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.74 | |

| LightGBM | 0.90 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.74 | |

| Catboost | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.31 | 0.73 | |

| Adolescents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | AUC(ROC) | |

| Random Forest | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | |

| XGBoost | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | |

| LightGBM | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.53 | |

| Catboost | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.56 | |

Performance comparison of machine learning models for children and adolescents without transfer learning (South America, 2015-2016).

For adolescents, the models also achieved high accuracy, with scores around 0.85 and 0.86. However, their discriminative ability, as measured by the AUC-ROC, was relatively low. CatBoost achieved the highest AUC-ROC value at 0.56, followed by LightGBM (0.53) and XGBoost (0.51). Random Forest showed the lowest discriminative ability, with an AUC-ROC of 0.46.

Table 3 presents the results after applying transfer learning to the models. All models exhibited consistent accuracy at 0.86, indicating strong overall performance in data classification. Notably, both LightGBM and CatBoost achieved a precision of 1.0, reflecting their enhanced ability to correctly identify positive cases and modest improvements compared to previous metrics. Regarding discriminative ability, as measured by the AUC-ROC, CatBoost achieved the highest score of 0.82, demonstrating superior capacity to distinguish between positive and negative cases after transfer learning.

TABLE 3

| Adolescents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | AUC(ROC) | |

| XGBoost | 0.86 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.77 | |

| LightGBM | 0.86 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.72 | |

| Catboost | 0.86 | 1.0 | 0.18 | 0.82 | |

Performance comparison of machine learning models for adolescents after applying transfer learning (South America, 2015-2016).

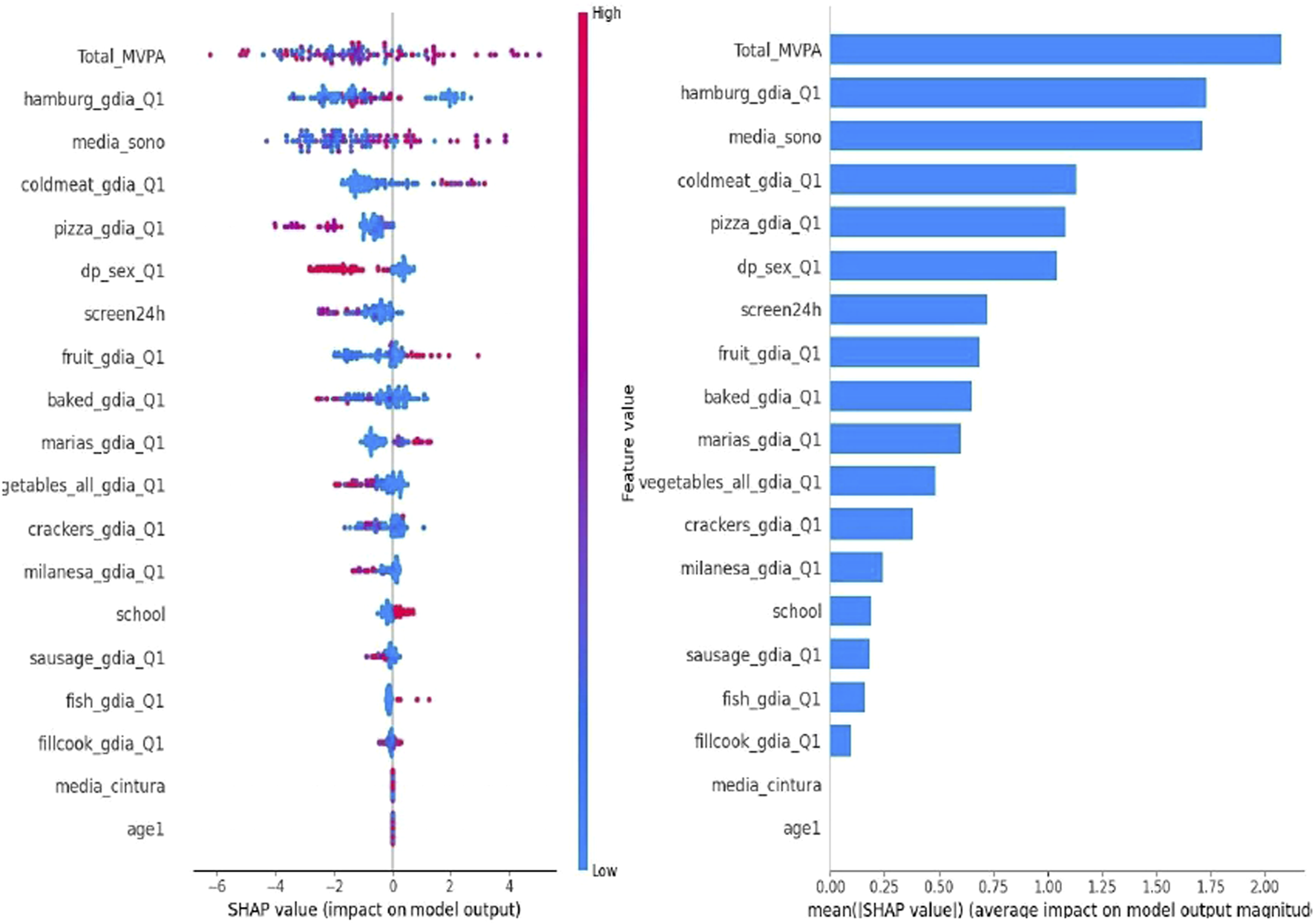

The SHAP plot (Figure 2A) provides a detailed analysis of the variables influencing hypertension prediction in the pediatric population. Key contributors to hypertension prediction included low physical activity, increased screen time, shorter sleep duration, higher waist circumference, and greater consumption of foods such as hamburgers, cold cuts, pizza, and sausages. Figure 2B illustrates the mean importance of these variables, offering a comprehensive view of their relative impact on the model. These findings provide valuable insights for the development of targeted preventive strategies and interventions to address hypertension in this age group.

FIGURE 2

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) Analysis {[Buenos Aires (Argentina), Lima (Peru), Medellin (Colombia), Montevideo (Uruguay), Santiago (Chile), and São Paulo and Teresina (Brazil). 2015/2016]}.

Discussion

In this multicentric observational study, algorithms were developed and evaluated to predict the presence of hypertension in the pediatric population across seven South American cities. The results demonstrate an improvement in predictive performance with the application of transfer learning (TL) in this population.

Hypertension prevention strategies can target the general population or specific high-risk groups. The increasing demand for early identification of at-risk individuals who could benefit from preventive interventions has driven interest in predictive models for hypertension [23]. While numerous models have been developed for the adult population using both traditional regression-based approaches and machine learning methods, there is a notable gap in pediatric-focused models [24, 32], because Pediatric hypertension affects approximately 11% of boys and 9.6% of girls globally, presenting a significant public health concern that the American Heart Association has recently highlighted as critical to address [37, 38].

This study builds on prior research by applying TL to predict hypertension in the pediatric population, proving it to be an effective strategy. A substantial sample of children was used to pre-train a model, which was then fine-tuned using the adolescent sample [34]. This approach leveraged general features from the larger and more robust dataset to adapt to the specific characteristics of adolescents. The results revealed a significant improvement in the AUC-ROC, highlighting the model’s enhanced ability to differentiate adolescents at risk for hypertension. These findings underscore the potential of TL in data-scarce contexts, maximizing the utility of available information and improving generalization and accuracy in predictions [35].

TL is a cornerstone of artificial intelligence (AI), enabling the reuse of pre-trained models for new tasks, thereby saving time and computational resources. This technique is particularly valuable in domains where acquiring large volumes of labeled data is challenging or costly. Studies have demonstrated that TL accelerates the development of AI solutions by leveraging knowledge from previously learned tasks, enhancing model efficiency and effectiveness [39]. Furthermore, TL democratizes AI by making advanced solutions accessible to organizations with limited resources, reducing the dependency on extensive datasets or advanced computing infrastructure. In healthcare, TL significantly enhances the predictive capabilities of models and broadens the applicability of AI technologies for early detection and disease management [3].

Although the application of SHAP in predicting hypertension in the pediatric population is still limited, recent studies have explored its use in related contexts. One study utilized SHAP to interpret machine learning models for hypertension risk prediction, identifying significant risk factors such as elevated LDL cholesterol levels and low HDL cholesterol levels [40, 41].

Our findings, corroborated by SHAP analysis, are consistent with existing literature linking sedentary lifestyles and diets high in processed foods to an increased risk of hypertension. The results emphasize the importance of interventions focused on promoting physical activity and healthy eating habits from childhood as crucial strategies for preventing hypertension and promoting long-term cardiovascular health. The inclusion of public policies and educational programs aimed at reducing screen time and improving sleep quality can also play a vital role in mitigating these risk factors [42].

Working with pediatric data to predict arterial hypertension presents several limitations that may impact the accuracy and applicability of predictive models. First, the inherent biological variability in growth and development during childhood leads to significant variations in physiological parameters, including blood pressure [43]. This variability makes the creation of robust and consistent predictive models a substantial challenge. Additionally, the definition of hypertension in children is based on age-, sex-, and height-adjusted percentiles, which adds a layer of complexity to standardizing diagnostic criteria and comparing different studies [36, 44]. Another limitation is data availability. Compared to adults, there is a significantly smaller amount of data on childhood hypertension, making it difficult to identify robust patterns and validate predictive models.

This study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size, particularly for the adolescent group, may impact the generalizability and robustness of the findings [4]. To address these limitations, a feasibility pilot study was conducted to validate the reliability of the methods, and statistical adjustments were made to account for the sample structure. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable insights into the early detection of hypertension in pediatric populations and highlights the need for future research with larger, more diverse samples to validate and extend the present findings.

Therefore, it is essential to continue expanding pediatric databases, improve data collection methods, standardize diagnostic criteria, and develop algorithms that consider the variability and particularities of the pediatric population to overcome these limitations and enhance the accuracy of predictive models [45, 46].

These findings have significant implications for developing intervention strategies and health policies to prevent and manage childhood hypertension. They highlight the potential of AI-based modeling approaches to identify and analyze risk factors in public health. Moreover, the results underscore the importance of individualized health promotion strategies that account for the diverse needs and behaviors of pediatric populations.

Conclusion

Machine learning models effectively identified key dietary predictors of elevated blood pressure in children and adolescents. High consumption of soft drinks, filled cookies, and chips were identified as significant risk factors, with adolescents exhibiting a higher intake of these foods compared to children. These findings emphasize the critical need to address unhealthy dietary habits through early prevention strategies aimed at reducing the risk of hypertension and fostering cardiovascular health in pediatric populations.

Statements

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Human Research Ethics Committee of the Medical School of the University of São Paulo (CAEE: 04900918.4.1001.0065). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors actively participated in different stages of the study. KA-M and AC were responsible for the planning and design of the study. KA-M, LS, and AD conducted the data collection, while KA-M, Td, LS, and MR performed the statistical analyses and interpretation of the results. KA-M wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with significant contributions to the discussion from AC, AD, and Td. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this research was provided by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq and the Department of Science and Technology of Secretariat of Science, Technology, Innovation and Health Complex of Ministry of Health of Brazil, under grant no. 445020/2023-7. Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo – FAPESP, no 2019/24224-1. Dr. De Moraes received the Start-Up Fund from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, School of Public Health, in Austin.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2025.1607944/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Mendis S Puska P Norrving B . Global Atlas' on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Heal Organ (2011).

2.

Mills KT Bundy JD Kelly TN Reed JE Kearney PM Reynolds K et al Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies from 90 Countries. Circulation (2016) 134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912

3.

Kalehoff JP Oparil S . The Story of the Silent Killer. Curr Hypertens Rep (2020) 22:1–14. 10.1007/s11906-020-01077-7

4.

Unger T Borghi C Charchar F Khan NA Poulter NR Prabhakaran D et al International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension (2020) 75:1334–57. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026

5.

Bao W Threefoot SA Srinivasan SR et al Essential Hypertension Predicted by Tracking of Elevated Blood Pressure from Childhood to Adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Hypertens (1995).

6.

Raitakari OT Juonala M Kähönen M et al Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Childhood and Carotid Artery Intima-Media Thickness in Adulthood: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. JAMA (2003) 290(17):2277–83. 10.1001/jama.290.17.2277

7.

Xia F Li Q Luo X Wu J . Identification for Heavy Metals Exposure on Osteoarthritis Among Aging People and Machine Learning for Prediction: A Study Based on NHANES 2011- 2020. Front Public Health (2022) 10:906774. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.906774

8.

Chiolero A Cachat F Burnier M Paccaud F Bovet P . Prevalence of Hypertension in School Children Based on Repeated Measurements and Association with Overweight. J Hypertens (2007) 25(11):2209–17. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef48b2

9.

Rosner B Cook NR Daniels S Falkner B . Childhood Blood Pressure Trends and Risk Factors for High Blood Pressure: The NHANES Experience 1988-2008. Hypertension (2013) 62(2):247–54. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00831

10.

Obermeyer Z Powers B Vogeli C Mullainathan S . Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used to Manage the Health of Populations. Science (2019) 366(6464):447–53. 10.1126/science.aax2342

11.

Panch T Mattie H Atun R . Artificial Intelligence and Algorithmic Bias: Implications for Health Systems. J Glob Health (2019) 9(2):010318. 10.7189/jogh.09.020318

12.

Handelman GS Kok HK Chandra RV Razavi AH Lee MJ Asadi H . eDoctor: Machine Learning and the Future of Medicine. J Intern Med (2018) 284:603–19. 10.1111/joim.12822

13.

Jiang Y Yang M Wang S Li X Sun Y . Emerging Role of Deep Learning-Based Artificial Intelligence in Tumor Pathology. Cancer Commun (Lond) (2020) 40:154–66. 10.1002/cac2.12012

14.

Sparano N et al Association between Sleep Duration and High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Sleep Med (2020) 16(6):935–45. 10.5664/jcsm.8354

15.

Zhu Y Yin H Xing Y Yu Z Luo J Karniadakis GE et al Deep Transfer Learning and Data Augmentation Improve Glucose Levels Prediction in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. npj Digital Med (2021) 4(1):109. 10.1038/s41746-021-00480-x

16.

Weng S Reps J Kai J Garibaldi JM Qureshi N . Can Machine-Learning Improve Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Using Routine Clinical Data?PLOS ONE (2017) 12(4):e0174944. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174944

17.

Moreno LA De Henauw S González-Gross M Kersting M Molnár D Gottrand F et al Design and Implementation of the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Obes (Lond) (2008) 32(Suppl. 5):S4–S11. 10.1038/ijo.2008.177

18.

Ahrens W Bammann K Siani A Buchecker K De Henauw S Iacoviello L et al The IDEFICS Cohort: Design, Characteristics and Participation in the Baseline Survey. Int J Obes (Lond) (2011) 35(Suppl. 1):S3–S15. 10.1038/ijo.2011.30

19.

Manios Y . The “ToyBox-Study” Obesity Prevention Programme in Early Childhood: An Introduction. Obes Rev (2012) 13(Suppl. 1):1–2. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00977.x

20.

Araújo-Moura K De Moraes ACF Forkert ECO Berg G Cucato GG Forjaz CLM et al Is the Measurement of Blood Pressure by Automatic Monitor in the South American Pediatric Population Accurate? SAYCARE Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2018) 26(Suppl. 1):S41-S46–S46. 10.1002/oby.22119

21.

American Heart Association (AHA), HallJEAppelLJFalknerBEGravesJHillMNet alRecommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans and Experimental Animals: Part 1: Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans: A Statement for Professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension (2005) 45:142–61. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e

22.

O'Brien E Petrie J Littler W de Swiet M Padfield PL Dillon MJ et al The British Hypertension Society Protocol for the Evaluation of Blood Pressure Measuring Devices. J Hypertens (1993) 11(Suppl. 2):S43–S62. 10.1097/00004872-199311002-00007

23.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: NHANES Procedure Manuals (2021)

24.

Chien KL Hsu HC Su TC Chang WT Sung FC Chen MF et al Prediction Models for the Risk of New Onset Hypertension in Ethnic Chinese in Taiwan. J Hum Hypertens (2011) 25:294–303. 10.1038/jhh.2010.63

25.

Carvalho HB Moreno LA Silva AM Berg G Estrada-Restrepo A González-Zapata LI et al Design and Objectives of the South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2018) 26(Suppl. 1):S5–S13. 10.1002/oby.22117

26.

De Moraes ACF Forkert ECO Vilanova-Campelo RC González-Zapata LI Azzaretti L Iguacel I et al Measuring Socioeconomic Status and Environmental Factors in the SAYCARE Study in South America: Reliability of the Methods. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2018) 26(Suppl. 1):S14-S22–S22. 10.1002/oby.22115

27.

Nascimento-Ferreira MV De Moraes ACF Toazza-Oliveira PV Forjaz CLM Aristizabal JC Santaliesra-Pasías AM et al Reliability and Validity of a Questionnaire for Physical Activity Assessment in South American Children and Adolescents: The SAYCARE Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) (2018) 26(Suppl. 1):S23-S30–S30. 10.1002/oby.22116

28.

De Moraes ACF Nascimento-Ferreira MV Forjaz CLM Aristizabal JC Azzaretti L Nascimento Junior WV et al Reliability and Validity of a Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire for South American Pediatric Population: SAYCARE Study. BMC Med Res Methodol (2020) 20(1):5. 10.1186/s12874-019-0893-7

29.

Rendo-Urteaga T Saravia L Sadalla Collese T Monsalve-Alvarez JM González-Zapata LI Tello F et al Reliability and Validity of an FFQ for South American Children and Adolescents from the SAYCARE Study. Public Health Nutr (2020) 23(1):13–21. 10.1017/S1368980019002064

30.

Collese TS De Moraes ACF Rendo-Urteaga T Luzia LA Rondó PHC Marchioni DML et al The Validity of Children's Fruit and Vegetable Intake Using Plasma Vitamins A, C, and E: The SAYCARE Study. Nutrients (2019) 11(8):1815. 10.3390/nu11081815

31.

González-Zapata LI Restrepo-Mesa SL Aristizabal JC Skapino E Collese TS Azzaretti LB et al Reliability and Validity of Body Weight and Body Image Perception in Children and Adolescents from the South American Youth/Child Cardiovascular and Environmental (SAYCARE) Study. Public Health Nutr (2019) 22(6):988–96. 10.1017/S1368980018004020

32.

Chowdhury MZI Turin TC . Precision Health through Prediction Modelling: Factors to Consider before Implementing a Prediction Model in Clinical Practice. J Prim Health Care (2020) 12:3–9. 10.1071/HC19087

33.

Arooj S Atta-Ur-Rahman Zubair M Khan MF Alissa K Khan MA et al Breast Cancer Detection and Classification Empowered with Transfer Learning. Front Public Health (2022) 10:924432. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.924432

34.

Dalkıran A Atakan A Rifaioğlu AS Martin MJ Atalay RÇ Acar AC et al Transfer Learning for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction. Bioinformatics (2023) 39(39 Suppl. 1):i103–i110. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad234

35.

Dey V Raghu M Xia N . Improving Compound Activity Classification via Deep Transfer and Representation Learning. ACS omega (2022) 7:9465–83. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06805

36.

Donmez TB Kutlu M Mustafa MM Yildiz Z . Explainable AI in Action: A Comparative Analysis of Hypertension Risk Factors Using SHAP and LIME. Neural Comput Appl (2024) 37:4053–74. 10.1007/s00521-024-10724-y

37.

De Moraes AC Lacerda MB Moreno LA Horta BL Carvalho HB . Prevalence of High Blood Pressure in 122,053 Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression. Medicine (Baltimore) (2014) 93:e232. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000232

38.

Falkner B Gidding SS Baker-Smith CM Brady TM Flynn JT Malle LM et al Pediatric Primary Hypertension: An Underrecognized Condition: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension (2023) 80:e101–e111. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000228

39.

Flynn JT Kaelber DC Baker-Smith CM Blowey D Carroll AE Daniels SR et al Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics (2017) 140(3):e20171904. 10.1542/peds.2017-1904

40.

Zuo D Yang L Jin Y Qi H Liu Y Ren L . Machine Learning-Based Models for the Prediction of Breast Cancer Recurrence Risk. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak (2023) 23(1):276. 10.1186/s12911-023-02377-z

41.

Lundberg SM Nair B Vavilala MS Horibe M Eisses MJ Adams T et al Explainable Machine-Learning Predictions for the Prevention of Hypoxaemia during Surgery. Nat Biomed Eng (2018) 2:749–60. 10.1038/s41551-018-0304-0

42.

Li X Zhao Y Zhang D Kuang L Huang H Chen W et al Development of an Interpretable Machine Learning Model Associated with Heavy Metals' Exposure to Identify Coronary Heart Disease Among US Adults via SHAP: Findings of the US NHANES from 2003 to 2018. Chemosphere (2023) 311(Pt 1):137039. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137039

43.

Sathish T Kannan S Sarma PS Razum O Thrift AG Thankappan KR . A Risk Score to Predict Hypertension in Primary Care Settings in Rural India. Asia-pacific J Public Heal (2016) 28:26S-31S–31S. 10.1177/1010539515604701

44.

Snell KIE Ensor J Debray TPA Moons KGM Riley RD . Meta-analysis of Prediction Model Performance across Multiple Studies: Which Scale Helps Ensure Between-Study Normality for the C-Statistic and Calibration Measures?Stat Methods Med Res (2018) 27:3505–22. 10.1177/0962280217705678

45.

Williams B Poulter NR Brown MJ Davis M McInnes GT Potter JF et al British Hypertension Society Guidelines for Hypertension Management. BMJ (2004) 328(7440):634–40. 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.634

46.

Geron A . Hands-on Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media, Inc. (2022).

Summary

Keywords

hypertension, machine learning, children, adolescents, public health

Citation

Araujo-Moura K, Souza L, de Oliveira TA, Rocha MS, De Moraes ACF and Chiavegatto Filho A (2025) Prediction of Hypertension in the Pediatric Population Using Machine Learning and Transfer Learning: A Multicentric Analysis of the SAYCARE Study. Int. J. Public Health 70:1607944. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2025.1607944

Received

09 September 2024

Accepted

25 February 2025

Published

11 March 2025

Volume

70 - 2025

Edited by

Paolo Chiodini, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy

Reviewed by

Mario Fordellone, Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy

One reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Araujo-Moura, Souza, de Oliveira, Rocha, De Moraes and Chiavegatto Filho.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandre Chiavegatto Filho, alexdiasporto@usp.br

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.