Abstract

Objective:

To determine the prevalence and sociodemographic profiles of mental morbidity and multimorbidity.

Methods:

A descriptive analysis was performed with data from 25,269 women and 8,389 men from the French NutriNet-Santé general-population cohort. Participants were split into 8 groups: 1. No mental morbidity; 2. Pure anxiety; 3. Pure insomnia; 4. Pure eating disorders (ED); 5. Comorbid anxiety and insomnia; 6. Comorbid anxiety and ED; 7. Comorbid insomnia and ED; 8. Multimorbid anxiety, insomnia, and ED. Data were weighted using the 2016 French Census and analyzed with Chi2 tests.

Results:

40.6% of the participants had ≥1 mental disorder; 2.3% had all 3 disorders. Most pure and comorbid disorders were more common in women than in men. The multimorbidity group had the largest proportions of men who were overweight (52.1%) and current smokers (23.2%). Men with insomnia and ED were the most likely to have obesity (45.8%) and low physical activity (44.3%). Women with ≥2 disorders were the most likely to be current smokers.

Conclusion:

The findings could inform research, prevention, and public health guidelines for multimorbidity.

Introduction

Suffering from ≥2 chronic conditions is termed comorbidity when one of the conditions is regarded as primary or multimorbidity (without a primary condition) [1]. Such phenomena are associated with symptom severity, increased healthcare utilization, and a poorer prognosis [2, 3]. The vast majority of comorbidity/multimorbidity research understandably addresses physical illnesses in elderly populations [4, 5]. From a public health viewpoint and irrespective of age, mental health receives less attention than physical health, despite its substantial contribution to disease burden, further worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic [6] and the marked reduction in life expectancy among individuals with mental illness compared with the general population [7, 8]. Findings from the 27-country World Health Organization (WHO) Mental Health Surveys revealed that each lifetime mental disorder was associated with a substantially increased risk of subsequent mental comorbidity, with the risk persisting over >15 years [9].

Here we focus on three mental health conditions - anxiety, insomnia, and eating disorders (ED) - because they are relatively frequent in the general population, display a strong potential for comorbidity, and offer opportunities for prevention or treatment [10–12]. The most common among them is anxiety (encompassing generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety, phobias, etc.) with prevalence estimates of 4%–25%, with higher rates among women, younger adults, and individuals with chronic illness [13]. During 1990–2019, disability-adjusted life years attributable to anxiety disorders increased worldwide by nearly 54% across age [14]. Next, a meta-analysis reported that not only anxiety but also many other mental disorders were concomitant with sleep disturbances, implying an imbalance in the arousal system [15]. Moreover, network analyses have provided evidence for connections among symptoms of anxiety, sleep disorders and ED [11].

The U.S. National Comorbidity Survey (baseline: 1990–1992; replication: 2001–2003) was among the first to address the prevalence and correlates of comorbid and multimorbid mental disorders [3, 16]. However, to date, few epidemiological studies have investigated the socio-demographic profiles of pure versus comorbid/multimorbid mental disorders in the general population [17–20] which is indispensable for identifying at-risk subgroups. To our knowledge, no prior epidemiological research has addressed the multimorbidity of anxiety, sleep disturbance/insomnia and ED in general-population adults. Only one small cross-sectional study with 130 Brazilian adults with overweight or obesity included measures of all three disorders and reported that adults aged <45 years with high trait anxiety also had high scores on binge eating and low scores on sleep quality, based on two-way correlations [21].

There is compelling need to advance mental multimorbidity research to inform targeted public health interventions. Therefore, this descriptive study investigated the prevalence and degree of mental multimorbidity, focusing on three mental health conditions and the socio-demographic characteristics of pure versus multimorbid cases. Given that women present higher rates of anxiety [13], insomnia [22] and ED [23], we explored sex-specific associations.

Methods

Research Context

This analysis is part of the 4-year MEMORIES Project, launched in France in 2022 (https://memories-anr.univ-paris13.fr/) and aimed at elucidating the risk of developing metabolic disorders (obesity and type 2 diabetes) associated with mental morbidity and multimorbidity [24].

Study Population

Epidemiological data for MEMORIES came from the ongoing NutriNet-Santé e-cohort (https://etude-nutrinet-sante.fr/) launched in 2009. Its design and objectives are detailed elsewhere [25]. Briefly, adults aged ≥18 years who comprehend written French and are able to follow an online protocol are recruited from the general population via media campaigns. NutriNet-Santé was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research and by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty. Electronic informed consent is obtained from each volunteer prior to enrollment.

Data are collected via self-report questionnaires. Sociodemographic, anthropometric, lifestyle, diet, physical activity, and health status information is gathered at inclusion and annually thereafter. Over the follow-up, participants complete additional questionnaires on nutrition or health-related topics on a voluntary basis. All mental health assessments (described below) took place as part of the general follow-up of the cohort.

Anxiety Assessment

The 20-item trait anxiety subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y (STAI-T) was used for evaluating general anxiety proneness, distinguishing it from depression [26, 27]. Trait anxiety measured by STAI-T was reported to be highly correlated with generalized anxiety disorder [28]. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “Almost never” to “Almost always.” The higher the score, the greater the proneness to anxiety. STAI-T was administered during 2013–2016 and each participant completed it only once. Of the 119,451 enrollees solicited, n = 40,809 responded. As in prior epidemiological research [29], we modelled STAI-T in quartiles (Q), with Q4 as the sex-specific cutoff defining high trait anxiety (men Q4 ≥ 41; women Q4 ≥ 46).

Insomnia Assessment

A sleep questionnaire was administered in 2014; of the 128,042 solicited participants, n = 57,105 responded within 6 months. The questionnaire included items about sleep duration, chronotype, acute and chronic insomnia, napping, and stress-related sleep disturbance. Here we focused on chronic insomnia assessed according to the criteria established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - 5th Edition (DSM-5) [30] and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders - 3rd Edition (ICSD-3) [31]. These criteria were included as questionnaire items and provide information about difficulties falling asleep and/or frequent nighttime wakening ≥3 nights/week, over the past ≥3 months, and the experience of negative repercussions of such problems in daily life.

Eating Disorder (ED) Assessment

We screened for any ED, without distinguishing the type, in 2014 and 2017 using the 5-item SCOFF questionnaire [32, 33]. Each item (e.g., “Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat?; “Would you say food dominates your life?) is dichotomous (Yes/No); an ED threshold is fixed at ≥2 affirmative responses, with sensitivity and specificity >94% using interviews as diagnostic reference [33]. Data obtained with SCOFF are regarded as reflecting likely ED, approximating actual ED point prevalence [34]. Of the 125,279 enrollees who received SCOFF in 2014, a total of n = 51,073 responded within 6 months. Participants who did not complete SCOFF in 2014 but did so in 2017 (n = 6,570) were also eligible for the study.

Sociodemographic Profile Assessment

At inclusion and annually thereafter, data on sex, age, marital status, education, occupation, smoking, anthropometrics, and physical activity were collected from all participants, using validated socio-demographic [35] and anthropometric [36, 37] questionnaires. From the reported weight and height, the body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) of each participant was calculated. Next, physical activity was assessed with the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and scoring followed an established algorithm [38].

For each participant, we first calculated the average date of completion of the three mental health assessments which covered the period 2013–2017. Next, we selected covariable data obtained within a 2-year window around that average date. Individuals with missing data on any covariables were ineligible for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Scores on each of the three mental health measures were dichotomized for each participant to reflect the presence or absence of the respective condition; 8 morbidity groups were thus created: no mental morbidity, pure anxiety, pure insomnia, pure ED (any type), comorbid anxiety and insomnia, comorbid anxiety and ED, comorbid insomnia and ED, multimorbid anxiety, insomnia, and ED. Next, we investigated the prevalence of mental morbidity and the sociodemographic characteristics of participants with one, two and all three mental health conditions. The following characteristics served as exposures: age (as a continuous and a 3-level variable: 18–39, 40–59, ≥60 years), marital status (living alone, married/cohabiting), education (< high school, high school or equivalent, some college, undergraduate/graduate degree), occupation/employment (without professional activity, self-employed/artisan/farmer, blue-collar worker, office/administrative staff, professional/executive staff, retired), BMI [kg/m2, as a continuous and a 4-level variable: underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9), obesity (≥30.0)], smoking status (never, former, current smoker), and physical activity level (low, moderate, high).

Statistical calibration was applied to the data via the SAS CALMAR macro developed by the French Census Bureau [39]. Specifically, we calculated and applied statistical weights according to the sex-, age- and socioeconomic status distribution in the 2016 French Census. The weighted data were then analyzed with Chi2 tests using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary NC, United States).

Results

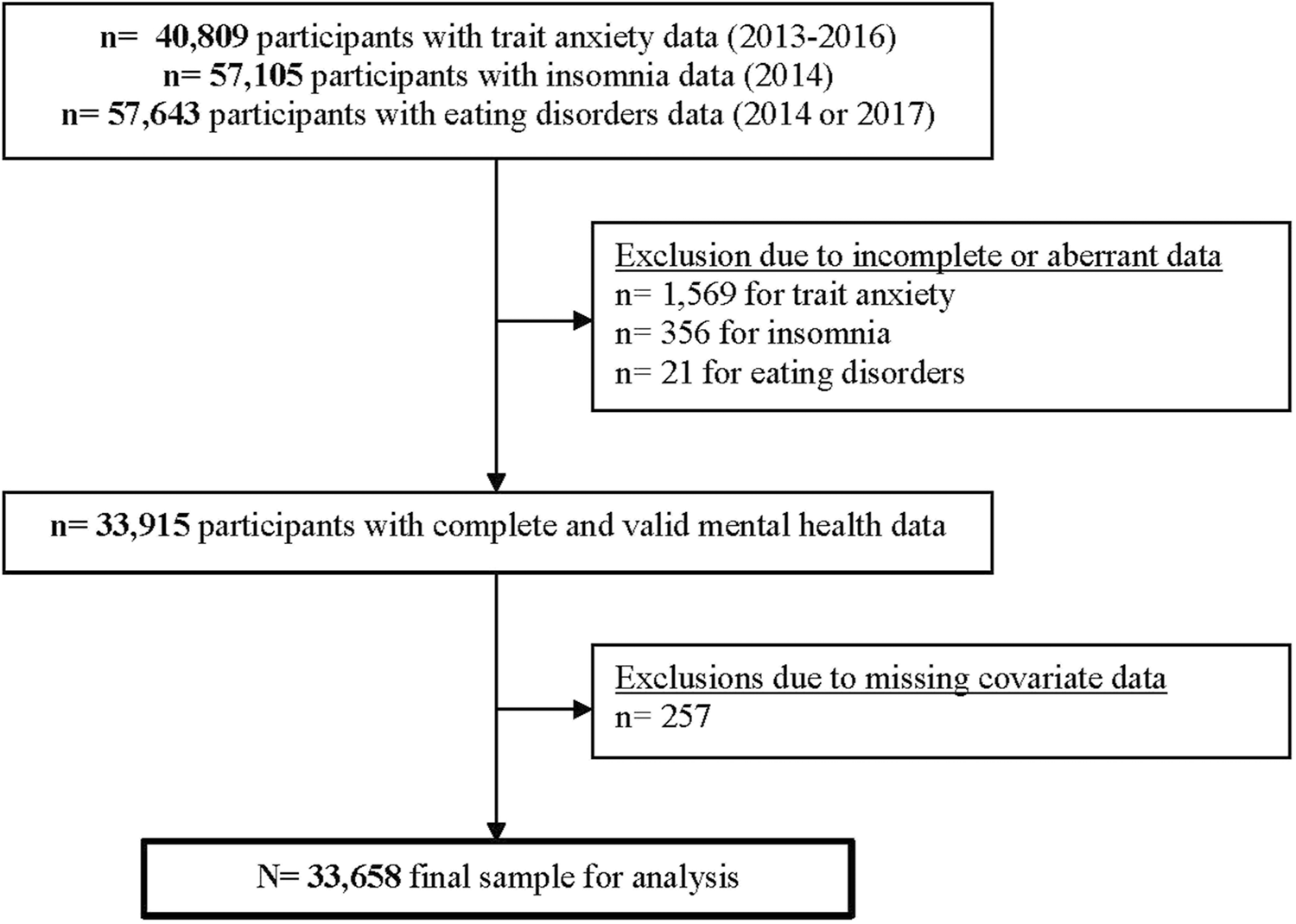

In total, N = 33,658 participants (25,269 women, 8,389 men) had complete and valid mental health and covariate data and were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The overall and sex-specific raw and weighted distribution of mental morbidity prevalence is summarized in Table 1. Overall, 40.6% (men 37.4%; women 43.6%) had ≥1 mental health condition; 2.3% had all three conditions (men 1.4%; women 3.1%). Across sex, the most prevalent comorbidity was anxiety and insomnia (men 6.1%; women 6.4%) whereas the least prevalent was insomnia and ED (men 0.9%; women 1.6%). The raw and weighted sociodemographic profiles associated with mental morbidity are presented in Table 2 (women) and Table 3 (men).

FIGURE 1

NutriNet-Santé participant selection flowchart (France, 2013–2017).

TABLE 1

| Full sample N = 33,658 |

Men n = 8,389 | Women n = 25,269 | Chi-squared test p-value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw data No. (%) |

W

a

% |

Raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

Raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

|||||

| General (trait) anxietyb | 0.42 | |||||||||

| No | 25,056 | (74.4) | 74.6 | 6,273 | (74.8) | 74.1 | 18,783 | (74.3) | 75.0 | |

| Yes | 8,602 | (25.6) | 25.4 | 2,116 | (25.2) | 25.9 | 6,486 | (25.7) | 25.0 | |

| Chronic insomniac | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| No | 26,933 | (80.0) | 81.5 | 7,274 | (86.7) | 85.2 | 19,659 | (77.8) | 78.2 | |

| Yes | 6,725 | (20.0) | 18.5 | 1,115 | (13.3) | 14.8 | 5,610 | (22.2) | 21.8 | |

| Eating disorder (any type)d | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| No | 29,376 | (87.3) | 87.9 | 7,757 | (92.5) | 91.0 | 21,619 | (85.6) | 85.1 | |

| Yes | 4,282 | (12.7) | 12.1 | 632 | (7.5) | 9.0 | 3,650 | (14.4) | 14.9 | |

| Degree of mental multimorbidity | <0.0001 | |||||||||

| None | 19,508 | (58.0) | 59.4 | 5,413 | (64.5) | 62.6 | 14,095 | (55.8) | 56.4 | |

| General (trait) anxiety | 4,453 | (13.2) | 13.6 | 1,368 | (16.3) | 15.8 | 3,085 | (12.2) | 11.7 | |

| Chronic insomnia | 3,235 | (9.6) | 8.7 | 508 | (6.1) | 6.5 | 2,727 | (10.8) | 10.6 | |

| Eating disorder only (any type) | 1,824 | (5.4) | 5.2 | 300 | (3.6) | 4.1 | 1,524 | (6.0) | 6.3 | |

| Anxiety and insomnia | 2,180 | (6.5) | 6.3 | 468 | (5.6) | 6.1 | 1,712 | (6.8) | 6.4 | |

| Anxiety and eating disorders | 1,148 | (3.4) | 3.2 | 193 | (2.3) | 2.6 | 955 | (3.8) | 3.8 | |

| Insomnia and eating disorders | 489 | (1.5) | 1.3 | 52 | (0.6) | 0.9 | 437 | (1.7) | 1.6 | |

| Anxiety, insomnia, and eating disorders | 821 | (2.4) | 2.3 | 87 | (1.0) | 1.4 | 734 | (2.9) | 3.1 | |

Distribution of mental morbidity prevalence: anxiety, insomnia, and eating disorders (NutriNet-Santé cohort, France. 2013–2017).

W = percentage obtained by applying statistical weights according to sex-, age- and socioeconomic status distribution in the 2016 French Census.

General anxiety proneness evaluated with STAI-T, applying sex-specific 75% cutoffs (men: 41 points; women: 46 points).

Chronic insomnia defined according to DSM-5 and ICSD-3 criteria.

Presence of any eating disorder defined as ≥2 affirmative responses on the SCOFF questionnaire.

TABLE 2

| No mental morbidity (n = 14,095) | Pure anxietya (n = 3,085) | Pure insomniab (n = 2,727) | Pure eating disordersc (n = 1,524) | Anxiety and insomnia (n = 1,712) | Anxiety and eating disorders (n = 955) | Insomnia and eating disorders (n = 437) | Anxiety, insomnia, and eating disorders (n = 734) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw data No. (%) |

W

d

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

|

| Age, years, mean, SD | 51.1 (13.9) | 48.3 (14.0) | 52.7 (12.1) | 49.3 (13.8) | 51.0 (12.6) | 46.4 (14.0) | 51.9 (11.6) | 47.9 (12.7) | ||||||||

| Age categories | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–39 years | 3,521 (25.0) | 30.4 | 985 (31.9) | 39.2 | 464 (17.0) | 20.3 | 423 (27.8) | 39.5 | 367 (21.5) | 30.6 | 344 (36.0) | 45.9 | 72 (16.5) | 19.9 | 211 (28.8) | 37.3 |

| 40–59 years | 5,825 (41.3) | 40.2 | 1,282 (41.6) | 40.7 | 1,396 (51.2) | 52.8 | 654 (42.9) | 42.7 | 865 (50.5) | 52.2 | 392 (41.1) | 42.1 | 237 (54.2) | 58.9 | 376 (51.2) | 52.2 |

| 60+ years | 4,749 (33.7) | 29.4 | 818 (26.5) | 20.1 | 867 (31.8) | 26.9 | 447 (29.3) | 17.8 | 480 (28.0) | 17.2 | 219 (22.9) | 12.0 | 128 (29.3) | 21.2 | 147 (20.0) | 10.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Living alone | 3,531 (25.0) | 27.5 | 884 (28.6) | 30.6 | 674 (24.7) | 22.8 | 403 (26.4) | 28.2 | 501 (29.3) | 28.4 | 299 (31.3) | 34.1 | 116 (26.5) | 28.2 | 240 (32.7) | 33.4 |

| Married, cohabiting | 10,564 (75.0) | 72.5 | 2,201 (71.4) | 69.4 | 2,053 (75.3) | 77.2 | 1,121 (73.6) | 71.8 | 1,211 (70.7) | 71.6 | 656 (68.7) | 65.9 | 321 (73.5) | 71.8 | 494 (67.3) | 66.6 |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||||||

| <High school | 2,315 (16.4) | 19.2 | 527 (17.1) | 21.3 | 432 (15.8) | 19.7 | 314 (20.6) | 21.4 | 320 (18.7) | 21.4 | 173 (18.1) | 19.4 | 92 (21.0) | 27.5 | 153 (20.8) | 24.9 |

| High school or equivalent | 1,854 (13.2) | 15.8 | 458 (14.8) | 16.8 | 375 (13.8) | 15.6 | 214 (14.0) | 16.6 | 283 (16.5) | 20.2 | 153 (16.0) | 22.2 | 71 (16.3) | 21.8 | 124 (16.9) | 20.6 |

| Some college | 4,796 (34.0) | 33.4 | 954 (30.9) | 29.1 | 1,001 (36.7) | 32.0 | 519 (34.1) | 32.2 | 582 (34.0) | 31.1 | 337 (35.3) | 30.4 | 145 (33.2) | 29.0 | 254 (34.6) | 30.1 |

| Undergraduate/graduate | 5,130 (36.4) | 31.6 | 1,146 (37.2) | 32.8 | 919 (33.7) | 32.7 | 477 (31.3) | 29.8 | 527 (30.8) | 27.3 | 292 (30.6) | 28.0 | 129 (29.5) | 21.7 | 203 (27.7) | 24.4 |

| Occupation/employment | ||||||||||||||||

| No professional activitye | 1,409 (10.0) | 28.8 | 458 (14.8) | 35.1 | 313 (11.5) | 29.6 | 148 (9.7) | 22.9 | 246 (14.4) | 31.7 | 151 (15.8) | 33.6 | 60 (13.7) | 31.2 | 137 (18.7) | 36.5 |

| Self-employed, artisan | 283 (2.0) | 2.5 | 38 (1.2) | 1.4 | 65 (2.4) | 3.1 | 30 (2.0) | 2.5 | 34 (2.0) | 2.6 | 22 (2.3) | 2.8 | 7 (1.6) | 1.9 | 11 (1.5) | 1.9 |

| Blue-collar worker | 2,116 (15.0) | 26.7 | 597 (19.4) | 30.5 | 413 (15.2) | 26.8 | 310 (20.3) | 38.2 | 351 (20.5) | 34.3 | 230 (24.1) | 37.2 | 83 (19.0) | 31.5 | 166 (22.6) | 36.8 |

| Administrative staff | 2,425 (17.2) | 7.9 | 531 (17.2) | 7.2 | 492 (18.0) | 8.5 | 244 (16.0) | 7.8 | 293 (17.1) | 7.3 | 161 (16.9) | 6.5 | 88 (20.2) | 9.9 | 126 (17.2) | 6.7 |

| Executive staff | 3,316 (23.5) | 16.5 | 690 (22.4) | 14.2 | 603 (22.1) | 15.4 | 350 (23.0) | 15.6 | 341 (19.9) | 12.9 | 190 (19.9) | 12.8 | 87 (19.9) | 14.3 | 144 (19.6) | 11.7 |

| Retired | 4,546 (32.3) | 17.6 | 771 (25.0) | 11.6 | 841 (30.8) | 16.6 | 442 (29.0) | 13.0 | 447 (26.1) | 11.2 | 201 (21.0) | 7.1 | 112 (25.6) | 11.2 | 150 (20.4) | 6.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean, SD | 23.4 (4.1) | 23.2 (4.2) | 23.8 (4.4) | 25.8 (5.7) | 23.6 (4.9) | 25.3 (6.4) | 26.4 (5.7) | 25.9 (6.4) | ||||||||

| BMI categories | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight <18.5 | 736 (5.2) | 6.1 | 209 (6.8) | 7.4 | 139 (5.1) | 6.3 | 56 (3.7) | 4.4 | 128 (7.5) | 8.8 | 83 (8.7) | 10.1 | 9 (2.1) | 3.3 | 56 (7.3) | 9.1 |

| Normal weight 18.5–24.9 | 9,689 (68.7) | 67.0 | 2,081 (67.5) | 65.0 | 1,755 (64.4) | 65.1 | 755 (49.5) | 51.0 | 1,080 (63.1) | 60.4 | 456 (47.8) | 50.3 | 193 (44.2) | 41.7 | 331 (45.1) | 46.9 |

| Overweight 25.0–29.9 | 2,678 (19.0) | 20.1 | 587 (19.0) | 21.3 | 584 (21.4) | 19.6 | 393 (25.8) | 25.4 | 330 (19.3) | 18.8 | 232 (24.3) | 22.4 | 135 (30.9) | 32.0 | 168 (22.9) | 21.5 |

| Obesity ≥30.0 | 992 (7.1) | 6.8 | 208 (6.7) | 6.3 | 249 (9.1) | 9.0 | 320 (21.0) | 19.2 | 174 (10.1) | 12.0 | 184 (19.2) | 17.2 | 100 (22.8) | 23.0 | 179 (24.7) | 22.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||||

| Never smoker | 7,704 (54.7) | 54.0 | 1,712 (55.5) | 57.2 | 1,381 (50.6) | 48.4 | 749 (49.1) | 52.0 | 872 (50.9) | 49.6 | 503 (52.7) | 49.4 | 179 (41.0) | 38.0 | 325 (44.3) | 46.0 |

| Former smoker | 4,951 (35.1) | 34.7 | 997 (32.3) | 30.2 | 1,063 (39.0) | 40.6 | 603 (39.6) | 36.1 | 645 (37.7) | 38.1 | 313 (32.8) | 31.8 | 206 (47.1) | 46.9 | 297 (40.4) | 37.3 |

| Current smoker | 1,440 (10.2) | 11.3 | 376 (12.2) | 12.6 | 283 (10.4) | 11.0 | 172 (11.3) | 11.9 | 195 (11.4) | 12.3 | 139 (14.5) | 18.8 | 52 (11.9) | 15.1 | 112 (15.3) | 16.7 |

| Physical activity levelf | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 3,003 (21.3) | 22.0 | 941 (30.5) | 33.3 | 660 (24.2) | 23.4 | 372 (24.4) | 24.5 | 456 (26.6) | 27.6 | 283 (29.6) | 32.0 | 133 (30.4) | 28.5 | 238 (32.4) | 33.0 |

| Moderate | 6,182 (43.9) | 44.3 | 1,292 (41.9) | 40.7 | 1,149 (42.1) | 44.3 | 629 (41.3) | 42.0 | 687 (40.1) | 36.9 | 402 (42.1) | 36.2 | 151 (34.6) | 39.1 | 285 (38.8) | 37.3 |

| High | 4,910 (34.8) | 33.7 | 852 (27.6) | 26.0 | 918 (33.7) | 32.3 | 523 (34.3) | 33.5 | 569 (33.3) | 35.5 | 270 (28.3) | 31.8 | 153 (35.0) | 32.4 | 211 (28.8) | 29.7 |

Socio-demographic characteristics of women according to mental morbidity status (NutriNet-Santé, n = 25,269, France. 2013–2017).

Values refer to number (percent) except when noted otherwise. Categorical variables compared across mental morbidity status using chi-squared tests; all p < 0.0001.

BMI, body mass index.

aGeneral anxiety proneness evaluated with the STAI-T, applying sex-specific 75% cutoffs (men: 41 points; women: 46 points).

bChronic insomnia defined according to DSM-5, and ICSD-3, criteria.

cPresence of any eating disorder defined as ≥2 affirmative responses on the SCOFF questionnaire.

dW = percentage obtained by applying statistical weights according to sex-, age- and socioeconomic status distribution in the 2016 French Census.

eThe category includes individuals who are unemployed, homemakers, on sick leave, students, or interns.

fPhysical activity was evaluated with the short form of the IPAQ, and scoring followed an established algorithm.

TABLE 3

| No mental morbidity (n = 5,413) | Pure anxietya (n = 1,368) | Pure insomniab (n = 508) | Pure eating disordersc (n = 300) | Anxiety and insomnia (n = 468) | Anxiety and eating disorders (n = 193) | Insomnia and eating disorders (n = 52) | Anxiety, insomnia, and eating disorders (n = 87) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw data No. (%) |

W d % | raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

raw data No. (%) |

W

% |

|

| Age, years, mean, SD | 58.7 (12.9) | 54.2 (14.4) | 58.8 (12.2) | 60.4 (11.5) | 54.2 (12.6) | 55.1 (13.4) | 57.8 (12.3) | 54.9 (11.5) | ||||||||

| Age categories | ||||||||||||||||

| 18–39 years | 584 (10.8) | 31.9 | 268 (19.6) | 41.0 | 41 (8.1) | 12.5 | 22 (7.3) | 15.6 | 58 (12.4) | 27.2 | 34 (17.6) | 31.7 | 6 (11.5) | 8.3 | 12 (13.8) | 29.0 |

| 40–59 years | 1,660 (30.7) | 43.8 | 513 (37.5) | 43.5 | 187 (36.8) | 64.1 | 88 (29.3) | 58.2 | 231 (49.4) | 60.5 | 70 (36.3) | 56.5 | 20 (38.5) | 72.0 | 44 (50.6) | 61.0 |

| 60+ years | 3,169 (58.5) | 24.3 | 587 (42.9) | 15.5 | 280 (55.1) | 23.4 | 190 (63.4) | 26.2 | 179 (38.4) | 12.3 | 89 (46.1) | 11.8 | 26 (50.0) | 19.7 | 31 (35.6) | 10.0 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||||

| Living alone | 818 (15.1) | 26.6 | 323 (23.6) | 40.2 | 85 (16.7) | 23.7 | 40 (13.3) | 17.0 | 128 (27.3) | 40.7 | 54 (28.0) | 60.7 | 7 (13.5) | 15.0 | 17 (19.5) | 20.8 |

| Married, cohabiting | 4,595 (84.9) | 73.4 | 1,045 (76.4) | 59.8 | 423 (83.3) | 76.3 | 260 (86.7) | 83.0 | 340 (72.7) | 59.3 | 139 (72.0) | 39.3 | 45 (86.5) | 85.0 | 70 (80.5) | 79.2 |

| Educational level | ||||||||||||||||

| < High school | 1,377 (25.4) | 24.0 | 297 (21.7) | 23.6 | 115 (22.7) | 30.7 | 113 (37.7) | 35.6 | 99 (21.1) | 30.3 | 64 (33.2) | 52.9 | 20 (38.5) | 60.1 | 26 (29.9) | 22.8 |

| High school or equivalent | 620 (11.5) | 15.6 | 174 (12.7) | 14.1 | 55 (10.8) | 13.9 | 37 (12.3) | 22.7 | 65 (13.9) | 12.2 | 27 (14.0) | 17.2 | 7 (13.5) | 6.6 | 14 (16.1) | 26.1 |

| Some college | 1,330 (24.6) | 29.4 | 338 (24.7) | 25.7 | 125 (24.6) | 23.3 | 58 (19.3) | 20.3 | 121 (25.9) | 23.8 | 50 (25.9) | 15.4 | 10 (19.2) | 12.7 | 20 (23.0) | 26.9 |

| Undergraduate/graduate | 2,086 (38.5) | 31.0 | 559 (40.9) | 36.6 | 213 (41.9) | 32.1 | 92 (30.7) | 21.4 | 183 (39.1) | 33.7 | 52 (26.9) | 14.5 | 15 (28.8) | 20.6 | 27 (31.0) | 24.2 |

| Occupation/employment | ||||||||||||||||

| No professional activitye | 155 (2.9) | 23.7 | 92 (6.7) | 35.2 | 20 (3.9) | 25.3 | 9 (3.0) | 19.9 | 35 (7.5) | 35.5 | 17 (8.8) | 41.9 | 3 (5.8) | 28.6 | 8 (9.2) | 39.2 |

| Self-employed, artisan | 109 (2.0) | 7.9 | 30 (2.2) | 4.4 | 10 (2.0) | 6.3 | 3 (1.0) | 2.1 | 19 (4.1) | 8.1 | 2 (1.0) | 2.1 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 3 (3.4) | 7.5 |

| Blue-collar worker | 323 (6.0) | 29.5 | 131 (9.6) | 30.0 | 29 (5.7) | 29.9 | 25 (8.3) | 43.6 | 48 (10.3) | 28.8 | 24 (12.4) | 32.5 | 6 (11.5) | 43.7 | 12 (13.8) | 30.4 |

| Administrative staff | 489 (9.0) | 12.1 | 174 (12.7) | 11.5 | 50 (9.9) | 13.9 | 26 (8.7) | 11.5 | 70 (14.9) | 11.7 | 31 (16.1) | 11.8 | 6 (11.5) | 10.1 | 14 (16.1) | 12.1 |

| Executive staff | 1,247 (23.0) | 10.2 | 381 (27.9) | 9.4 | 125 (24.6) | 10.2 | 54 (18.0) | 6.7 | 129 (27.5) | 8.4 | 31 (16.1) | 4.2 | 9 (17.3) | 6.2 | 18 (20.7) | 5.6 |

| Retired | 3,090 (57.1) | 16.6 | 560 (40.9) | 9.5 | 274 (53.9) | 14.4 | 183 (61.0) | 16.2 | 167 (35.7) | 7.5 | 88 (45.6) | 7.5 | 28 (53.9) | 11.4 | 32 (36.8) | 5.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean, SD | 25.2 (3.5) | 24.8 (3.8) | 25.3 (3.6) | 28.3 (4.4) | 25.4 (3.9) | 28.2 (5.0) | 29.0 (5.8) | 28.4 (4.8) | ||||||||

| BMI categories | ||||||||||||||||

| Underweight <18.5 | 27 (0.5) | 1.4 | 34 (2.5) | 3.2 | 6 (1.2) | 1.4 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 4 (0.9) | 3.8 | 1 (0.5) | 0.2 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Normal weight 18.5–24.9 | 2,920 (53.9) | 60.7 | 760 (55.6) | 54.9 | 255 (50.2) | 53.4 | 72 (24.0) | 32.9 | 248 (53.0) | 47.1 | 57 (29.6) | 14.5 | 16 (30.8) | 26.1 | 21 (24.2) | 10.3 |

| Overweight 25.0–29.9 | 1,990 (36.8) | 30.4 | 448 (32.7) | 32.1 | 198 (39.0) | 34.2 | 137 (45.7) | 36.9 | 169 (36.1) | 34.9 | 79 (40.9) | 40.4 | 17 (32.7) | 28.1 | 39 (44.8) | 52.1 |

| Obesity ≥30.0 | 476 (8.8) | 7.5 | 126 (9.2) | 9.8 | 49 (9.6) | 11.0 | 91 (30.3) | 30.2 | 47 (10.0) | 14.2 | 56 (29.0) | 44.9 | 19 (36.5) | 45.8 | 27 (31.0) | 37.6 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||||||

| Never smoker | 2,197 (40.6) | 45.9 | 622 (45.5) | 52.4 | 171 (33.7) | 41.1 | 102 (34.0) | 45.5 | 189 (40.4) | 41.8 | 70 (36.3) | 48.3 | 13 (25.0) | 29.3 | 28 (32.2) | 44.6 |

| Former smoker | 2,744 (50.7) | 40.5 | 611 (44.6) | 36.0 | 289 (56.9) | 43.3 | 175 (58.3) | 41.4 | 217 (46.4) | 44.6 | 105 (54.4) | 47.1 | 35 (67.3) | 62.9 | 49 (56.3) | 32.2 |

| Current smoker | 472 (8.7) | 13.6 | 135 (9.9) | 11.6 | 48 (9.4) | 15.6 | 23 (7.7) | 13.1 | 62 (13.2) | 13.6 | 18 (9.3) | 4.6 | 4 (7.7) | 7.8 | 10 (11.5) | 23.2 |

| Physical activity levelf | ||||||||||||||||

| Low | 923 (17.1) | 17.4 | 318 (23.2) | 24.7 | 86 (16.9) | 18.3 | 68 (22.7) | 30.2 | 123 (26.3) | 33.1 | 52 (26.9) | 34.9 | 17 (32.7) | 44.3 | 16 (18.4) | 18.9 |

| Moderate | 1,804 (33.3) | 35.4 | 528 (38.6) | 39.0 | 199 (39.2) | 38.3 | 97 (32.3) | 36.4 | 160 (34.2) | 29.2 | 72 (37.3) | 30.7 | 14 (26.9) | 36.8 | 36 (41.4) | 33.3 |

| High | 2,686 (49.6) | 47.2 | 522 (38.2) | 36.3 | 223 (43.9) | 43.4 | 135 (45.0) | 33.4 | 185 (39.5) | 37.7 | 69 (35.8) | 34.4 | 21 (40.4) | 18.9 | 35 (40.2) | 47.8 |

Socio-demographic characteristics of men according to mental morbidity status (NutriNet-Santé, n = 8,389, France. 2013–2017).

Values refer to number (percent) except when noted otherwise. Categorical variables compared across mental morbidity status using chi-squared tests; all p < 0.0001.

BMI, body mass index.

General anxiety proneness evaluated with STAI-T, applying sex-specific 75% cutoffs (men: 41 points; women: 46 points).

Chronic insomnia defined according to DSM-5, and ICSD-3, criteria.

Presence of any eating disorder defined as ≥2 affirmative responses on the SCOFF questionnaire.

W = percentage obtained by applying statistical weights according to sex-, age- and socioeconomic status distribution in the 2016 French Census.

The category includes individuals who are unemployed, homemakers, on sick leave, students, or interns.

Physical activity evaluated with the short form of the IPAQ, and scoring followed an established algorithm.

Sociodemographic Profiles of Anxiety, Insomnia, and Eating Disorders Among Women

The largest proportion (45.9%) of women aged 18–39 years was found in the comorbid anxiety and ED group while the smallest proportion (10.5%) of women aged ≥60 years was found in the multimorbid anxiety-insomnia-ED group. The multimorbidity group also had the smallest proportions of women with executive positions or retired women (11.7% and 6.4%, respectively). Women with comorbid anxiety and ED had the highest prevalence of underweight (10.1%) and current smoking (18.8%) whereas women with insomnia and ED had the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity (31.9% and 23.0%, respectively).

Sociodemographic Profiles of Anxiety, Insomnia, and Eating Disorders Among Men

Distinct sociodemographic profiles associated with mental morbidity in men were found (Table 3). The multimorbidity group had the smallest proportions of men aged ≥60 years (10.0%) and men without high school education (22.8%); in turn, it had the largest proportions of men who are overweight (52.1%) and current smokers (23.2%). Next, men with comorbid anxiety and ED were the most likely to be without professional activity (41.9%) and to live alone (60.7%) whereas men with comorbid insomnia and ED were the most likely to have obesity (45.8%) and low physical activity (44.3%).

Discussion

According to WHO, mental disorders are widespread, undertreated, and under-resourced [6]. To help address this issue, this large, descriptive study focused on anxiety, insomnia, and ED owing to their relatively high prevalence and comorbidity in the general adult population, and the potential for prevention or treatment [10–12]. Among 33,658 individuals, a weighted total of 40.6% presented ≥1 mental disorder and an absolute total of 821 participants presented anxiety-insomnia-ED multimorbidity. Women were twice as likely as were men to have the latter (3.1% vs 1.4%, respectively). For most pure and comorbid conditions, women were at higher risk than were men.

Some distinct sex-specific sociodemographic profiles of mental morbidity emerged. Among women, having any ≥2 mental health conditions was associated with a higher prevalence of smoking than having ≤1 condition. Such a trend was absent among men. The largest proportions of younger adults (aged 18–39 years) were found among women with comorbid anxiety and ED and among men with pure anxiety, whereas the largest proportions of adults with obesity were found among those with comorbid insomnia and ED, across sex. Multimorbidity was associated with more risk behaviors among men than among women. The anxiety-insomnia-ED multimorbidity group had the largest proportions of men who were overweight (52.1%) and current smokers (23.2%), while no such trends emerged in women. These findings are not fully consistent with prior research in college students, showing that those with anxiety and/or mood disorders were more likely to be daily tobacco users compared to their counterparts without such mental disorders [40].

The present findings are largely consistent with prior mental health research reporting a high level of psychiatric comorbidity in the general population, observing that risk factor profiles for comorbid disorders differed considerably from those for pure disorders; such observations have important implications for prevention and clinical practice [17]. In addition, prior research regarding the 12-month comorbidity of anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders reported that the odds ratios for parental psychiatric history and childhood trauma were higher for comorbid anxiety-mood disorder, suggesting increased vulnerability and a more severe condition, than for either disorder in its pure form [17]. Also congruent with the present findings are previous reports of a positive association of mental comorbidity with female sex, living alone, and being of low socio-economic status [17–20]. Low physical activity and obesity have likewise been individually and positively associated with anxiety, ED, and insomnia/sleep disorders [41–45]. Even though ED types were not assessed in this study, the results regarding the prevalence of obesity suggest that restrictive types were unlikely to have driven the associations.

The frequent comorbidity of mental disorders, the shared risk factors and genetic expressions, and the observed activation in the same brain regions, especially those involved in emotion, learning and memory [7, 9, 46] have led some researchers to challenge the traditional view of mental disorders as distinct entities. To explain the underlying structure of mental illness, researchers have even proposed a general psychopathology continuum termed the “p factor” [47]. Likewise, the WHO stresses that mental health exists on a complex continuum [6]. Many physiological, genetic, affective, and cognitive mechanisms have been implicated in mental multimorbidity. For example, the association between anxiety and insomnia has been postulated to be driven by common gene variant heritability, dysregulation in circadian clock gene expression, serotonin, dopamine, and inflammatory cytokine secretion, and by cognitive inflexibility, interpretational biases, rumination tendencies, and impaired social interactions [48–50]. In addition, the role of the microbiome and the gut-brain axis in mental health have been attracting attention due to their involvement in numerous neuroendocrine, immune, inflammatory, and neurotransmitter pathways [51]. The bidirectional gut-brain communication is mediated by neural and humoral mechanisms. Whereas much work remains to be done in this area, it is known that intestinal dysbiosis and behavioral impairment are bidirectionally linked [51].

This descriptive study provided weighted prevalence estimates which argues for the external validity of the findings and against any selection bias. Specifically, the weighting largely compensated for differences (e.g., age, sex, educational level) between the study participants and the general French population. However, the cross-sectional design precludes any inference of causality. Likewise, the chronology of the three mental health conditions was beyond the scope of the study. There is evidence of complex bidirectional and possibly mediated associations among anxiety, insomnia, and ED [52–55]. Future longitudinal research could shed light on all of these issues. Another limitation, common to epidemiological research, pertains to the use of self-reported data provided by volunteers. We relied on DSM-5 and ICSD-3 criteria for insomnia, and on validated tools for anxiety (STAI-T) and ED (SCOFF); however, data obtained with these tools cannot serve as evidence for clinical diagnoses. A limitation of SCOFF is the lack of distinction among the various ED types. It should also be acknowledged that racial/ethnic background is an important component of the sociodemographic profile, however, such information was not available in our database.

In conclusion, this weighted analysis provided information about the prevalence and degree of mental multimorbidity of anxiety, insomnia, and ED among adults in the general population. Some distinct sex-specific sociodemographic profiles of mental morbidity emerged, which could be taken into consideration by targeted prevention programs, future cross-sectional and longitudinal mental multimorbidity research, and could help generate novel moderation and mediation hypotheses. In addition, the prevalence of mental comorbidity and multimorbidity justifies future methodological work aimed at generating mental multimorbidity composite measures. The findings also support the adaptation of medical education, public health guidelines, and healthcare services for multimorbidity [56, 57]. The advent of artificial intelligence in mental health will further necessitate the elaboration of novel regulatory frameworks, guidelines, and policies [58].

Statements

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM # 00000388FWA00005831) and by the National Commission on Informatics and Liberty (CNIL # 908450 and # 909216). Electronic informed consent is obtained from each volunteer prior to enrollment. NutriNet-Santé is registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (# NCT03335644). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

VAA, SC, CS, MC-B, and LKF designed and implemented the MEMORIES research project; PG, SH, and MT designed and implemented the NutriNet-Santé cohort; VAA and PG implemented the STAI and sleep questionnaires and coordinated anxiety and insomnia data collection; VAA implemented the SCOFF questionnaire and coordinated eating disorder data collection; VAA conceptualized the study, designed the analytic strategy, performed the literature review, and led the writing; NA performed the statistical analyses; all authors assisted with interpretation of the data, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The MEMORIES project is funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) (grant #ANR-21-CE36-0003; Dr. Andreeva-PI). The NutriNet-Santé study is supported by the French Ministry of Solidarity and Health, the National Agency for Public Health (Santé Publique France), the National Institute for Health and Medical Research (INSERM), the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE), the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (CNAM), and Sorbonne Paris Nord University. PD is funded by a doctoral fellowship from the French National Research Agency (ANR) (grant #ANR-21-CE36-0003). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Tugwell P Knottnerus JA . Multimorbidity and Comorbidity Are Now Separate MESH Headings. J Clin Epidemiol (2019) 105. vi-viii. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.019

2.

Coste J Valderas JM Carcaillon-Bentata L . Estimating and Characterizing the Burden of Multimorbidity in the Community: A Comprehensive Multistep Analysis of Two Large Nationwide Representative Surveys in France. Plos Med (2021) 18(4):e1003584. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003584

3.

Kessler RC Chiu WT Demler O Merikangas KR Walters EE . Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2005) 62(6):617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

4.

Diederichs C Berger K Bartels DB . The Measurement of Multiple Chronic Diseases-A Systematic Review on Existing Multimorbidity Indices. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2011) 66(3):301–11. 10.1093/gerona/glq208

5.

Ho IS Azcoaga-Lorenzo A Akbari A Black C Davies J Hodgins P et al Examining Variation in the Measurement of Multimorbidity in Research: A Systematic Review of 566 Studies. Lancet Public Health (2021) 6(8):e587–97. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00107-9

6.

World Health Organization (WHO). World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Geneva: WHO (2022).

7.

World Health Organization (WHO). Integrating the Prevention, Treatment and Care of Mental Health Conditions and Other NCDs within Health Systems. WHO European High-level Conference on Noncommunicable Diseases, 9-10 April 2019, Ashgabat (Turkmenistan). Report # WHO/EURO:2019-3647-43406-60946. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe (2019).

8.

Chesney E Goodwin GM Fazel S . Risks of All-Cause and Suicide Mortality in Mental Disorders: A Meta-Review. World Psychiatry (2014) 13(2):153–60. 10.1002/wps.20128

9.

McGrath JJ Lim CCW Plana-Ripoll O Holtz Y Agerbo E Momen NC et al Comorbidity within Mental Disorders: A Comprehensive Analysis Based on 145 990 Survey Respondents From 27 Countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (2020) 29:e153. 10.1017/S2045796020000633

10.

Ohayon MM Caulet M Lemoine P . Comorbidity of Mental and Insomnia Disorders in the General Population. Compr Psychiatry (1998) 39(4):185–97. 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90059-1

11.

Ralph-Nearman C Williams BM Ortiz AML Smith AR Levinson CA . Pinpointing Core and Pathway Symptoms Among Sleep Disturbance, Anxiety, Worry, and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Anorexia Nervosa and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa. J Affect Disord (2021) 294:24–32. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.061

12.

DeMartini J Patel G Fancher TL . Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Ann Intern Med (2019) 170(7):ITC49-ITC64–64. 10.7326/AITC201904020

13.

Remes O Brayne C van der Linde R Lafortune L . A Systematic Review of Reviews on the Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders in Adult Populations. Brain Behav (2016) 6(7):e00497. 10.1002/brb3.497

14.

Diseases Injuries Collaborators GBD . Global Burden of 369 Diseases and Injuries in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (2020) 396(10258):1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

15.

Baglioni C Nanovska S Regen W Spiegelhalder K Feige B Nissen C et al Sleep and Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Polysomnographic Research. Psychol Bull (2016) 142(9):969–90. 10.1037/bul0000053

16.

Harvard Medical School. National Comorbidity Survey (2005) Available from: https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/Boston:HarvardMedicalSchool(Accessed October 1, 2024)

17.

de Graaf R Bijl RV Smit F Vollebergh WA Spijker J . Risk Factors for 12-Month Comorbidity of Mood, Anxiety, and Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Am J Psychiatry (2002) 159(4):620–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.620

18.

Meng X D'Arcy C . Common and Unique Risk Factors and Comorbidity for 12-month Mood and Anxiety Disorders Among Canadians. Can J Psychiatry (2012) 57(8):479–87. 10.1177/070674371205700806

19.

Lepine JP Gasquet I Kovess V Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S Negre-Pages L Nachbaur G et al Prevalence and Comorbidity of Psychiatric Disorders in the French General Population. Encephale (2005) 31(2):182–94. 10.1016/s0013-7006(05)82385-1

20.

Barr PB Bigdeli TB Meyers JL . Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Sociodemographic Correlates of Psychiatric Disorders Reported in the All of Us Research Program. JAMA Psychiatry (2022) 79(6):622–8. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0685

21.

Fusco SFB Amancio SCP Pancieri AP Alves M Spiri WC Braga EM . Anxiety, Sleep Quality, and Binge Eating in Overweight or Obese Adults. Rev Esc Enferm USP (2020) 54:e03656. 10.1590/S1980-220X2019013903656

22.

Morin CM Jarrin DC . Epidemiology of Insomnia: Prevalence, Course, Risk Factors, and Public Health Burden. Sleep Med Clin (2022) 17(2):173–91. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.03.003

23.

Galmiche M Dechelotte P Lambert G Tavolacci MP . Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000-2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am J Clin Nutr (2019) 109(5):1402–13. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

24.

Agence Nationale de la Recherche. Mental Health Status as a Determinant of Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases: MEMORIES. Paris, France: Agence Nationale de la Recherche (2021). Available from: https://anr.fr/Project-ANR-21-CE36-0003Paris. (Accessed October 1, 2024)

25.

Hercberg S Castetbon K Czernichow S Malon A Mejean C Kesse E et al The NutriNet-Santé Study: A Web-Based Prospective Study on the Relationship between Nutrition and Health and Determinants of Dietary Patterns and Nutritional Status. BMC Public Health (2010) 10:242. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-242

26.

Spielberger CD . Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press (1983).

27.

Bruchon-Schweitzer M Paulhan I . STAI-Y: Inventaire D'anxiété État-Trait Forme Y/C. D. Spielberger. Paris: Éditions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée (1993).

28.

Chambers JA Power KG Durham RC . The Relationship between Trait Vulnerability and Anxiety and Depressive Diagnoses at Long-Term Follow-Up of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J Anxiety Disord (2004) 18(5):587–607. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.09.001

29.

Sugano Y Miyachi T Ando T Iwata T Yamanouchi T Mishima K et al Diabetes and Anxiety Were Associated with Insomnia Among Japanese Male Truck Drivers. Sleep Med (2022) 90:102–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2022.01.014

30.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5). Washington: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

31.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed.American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014). (ICSD-3). Darien.

32.

Morgan JF Reid F Lacey JH . The SCOFF Questionnaire: Assessment of a New Screening Tool for Eating Disorders. BMJ (1999) 319(7223):1467–8. 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467

33.

Garcia FD Grigioni S Chelali S Meyrignac G Thibaut F Dechelotte P . Validation of the French Version of SCOFF Questionnaire for Screening of Eating Disorders Among Adults. World J Biol Psychiatry (2010) 11(7):888–93. 10.3109/15622975.2010.483251

34.

Botella J Sepulveda AR Huang H Gambara H . A Meta-Analysis of the Diagnostic Accuracy of the SCOFF. Span J Psychol (2013) 16:E92. 10.1017/sjp.2013.92

35.

Vergnaud AC Touvier M Mejean C Kesse-Guyot E Pollet C Malon A et al Agreement between Web-Based and Paper Versions of a Socio-Demographic Questionnaire in the NutriNet-Sante Study. Int J Public Health (2011) 56(4):407–17. 10.1007/s00038-011-0257-5

36.

Touvier M Mejean C Kesse-Guyot E Pollet C Malon A Castetbon K et al Comparison between Web-Based and Paper Versions of a Self-Administered Anthropometric Questionnaire. Eur J Epidemiol (2010) 25(5):287–96. 10.1007/s10654-010-9433-9

37.

Lassale C Peneau S Touvier M Julia C Galan P Hercberg S et al Validity of Web-Based Self-Reported Weight and Height: Results of the Nutrient-Sante Study. J Med Internet Res (2013) 15(8):e152. 10.2196/jmir.2575

38.

Craig CL Marshall AL Sjostrom M Bauman AE Booth ML Ainsworth BE et al International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country Reliability and Validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2003) 35(8):1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

39.

Sautory O . Les Méthodes de Calage. Paris: Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE), Département des méthodes statistiques (2018)

40.

Boehm MA Lei QM Lloyd RM Prichard JR . Depression, Anxiety and Tobacco Use: Overlapping Impediments to Sleep in a National Sample of College Students. J Am Coll Health (2016) 64(7):565–74. 10.1080/07448481.2016.1205073

41.

Gariepy G Nitka D Schmitz N . The Association between Obesity and Anxiety Disorders in the Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) (2010) 34(3):407–19. 10.1038/ijo.2009.252

42.

McDowell CP Dishman RK Gordon BR Herring MP . Physical Activity and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am J Prev Med (2019) 57(4):545–56. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.05.012

43.

Scott KM Bruffaerts R Simon GE Alonso J Angermeyer M de Girolamo G et al Obesity and Mental Disorders in the General Population: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Int J Obes (Lond) (2008) 32(1):192–200. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803701

44.

Andreeva VA Torres MJ Druesne-Pecollo N Leger D Gonzalez P Bayon V et al Sex-specific Associations of Different Anthropometric Indices with Acute and Chronic Insomnia. Eur J Public Health (2017) 27(6):1026–31. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx123

45.

Andreeva VA Tavolacci MP Galan P Ladner J Buscail C Peneau S et al Sociodemographic Correlates of Eating Disorder Subtypes Among Men and Women in France, with a Focus on Age. J Epidemiol Community Health (2019) 73(1):56–64. 10.1136/jech-2018-210745

46.

Brainstorm C Anttila V Bulik-Sullivan B Finucane HK Walters RK Bras J et al Analysis of Shared Heritability in Common Disorders of the Brain. Science (2018) 360(6395):eaap8757. 10.1126/science.aap8757

47.

Caspi A Houts RM Belsky DW Goldman-Mellor SJ Harrington H Israel S et al The P-Factor: One General Psychopathology Factor in the Structure of Psychiatric Disorders? Clin Psychol Sci (2014) 2(2):119–37. 10.1177/2167702613497473

48.

Purves KL Coleman JRI Meier SM Rayner C Davis KAS Cheesman R et al A Major Role for Common Genetic Variation in Anxiety Disorders. Mol Psychiatry (2020) 5(12):3292–303. 10.1038/s41380-019-0559-1

49.

Harvey AG Murray G Chandler RA Soehner A . Sleep Disturbance as Transdiagnostic: Consideration of Neurobiological Mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev (2011) 31(2):225–35. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.003

50.

Blake MJ Trinder JA Allen NB . Mechanisms Underlying the Association between Insomnia, Anxiety, and Depression in Adolescence: Implications for Behavioral Sleep Interventions. Clin Psychol Rev (2018) 63:25–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.006

51.

Bruce-Keller AJ Salbaum JM Berthoud HR . Harnessing Gut Microbes for Mental Health: Getting from Here to There. Biol Psychiatry (2018) 83(3):214–23. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.014

52.

Alvaro PK Roberts RM Harris JK . A Systematic Review Assessing Bidirectionality between Sleep Disturbances, Anxiety, and Depression. Sleep (2013) 36(7):1059–68. 10.5665/sleep.2810

53.

Deboer LB Smits JA . Anxiety and Disordered Eating. Cognit Ther Res (2013) 37(5):887–9. 10.1007/s10608-013-9565-9

54.

Goel NJ Sadeh-Sharvit S Trockel M Flatt RE Fitzsimmons-Craft EE Balantekin KN et al Depression and Anxiety Mediate the Relationship between Insomnia and Eating Disorders in College Women. J Am Coll Health (2021) 69(8):976–81. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1710152

55.

Kenny TE Van Wijk M Singleton C Carter JC . An Examination of the Relationship between Binge Eating Disorder and Insomnia Symptoms. Eur Eat Disord Rev (2018) 26(3):186–96. 10.1002/erv.2587

56.

Barnett K Mercer SW Norbury M Watt G Wyke S Guthrie B . Epidemiology of Multimorbidity and Implications for Health Care, Research, and Medical Education: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet (2012) 380(9836):37–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

57.

Colombo F Garcia-Goni M Schwierz C . Addressing Multimorbidity to Improve Healthcare and Economic Sustainability. J Comorb (2016) 6(1):21–7. 10.15256/joc.2016.6.74

58.

Pandi-Perumal SR Narasimhan M Seeman MV Jahrami H . Artificial Intelligence Is Set to Transform Mental Health Services. CNS Spectr (2023) 29:155–7. 10.1017/S1092852923002456

Summary

Keywords

anxiety, eating disorders, insomnia, mental multimorbidity, general population

Citation

Andreeva VA, Arnault N, Chambaron S, Samieri C, Brindisi M-C, Duquenne P, Hercberg S, Galan P, Touvier M and Fezeu LK (2024) Mental Multimorbidity Among General-Population Adults: Sex-Specific Sociodemographic Profiles of Anxiety, Insomnia, and Eating Disorders. Int J Public Health 69:1607546. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1607546

Received

23 May 2024

Accepted

14 October 2024

Published

28 October 2024

Volume

69 - 2024

Edited by

Franco Mascayano, New York State Psychiatric Institute (NYSPI), United States

Reviewed by

Jesus Alejandro Aldana Lopez, Instituto Jalisciense de Salud Mental, Mexico

Erwin Calgua, Facultad de Ciencias Médicas Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala

One reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Andreeva, Arnault, Chambaron, Samieri, Brindisi, Duquenne, Hercberg, Galan, Touvier and Fezeu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valentina A. Andreeva, v.andreeva@eren.smbh.univ-paris13.fr

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.