- 1Faculty of Medicine, Beirut Arab University, Beirut, Lebanon

- 2Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon

Objective: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of medical student mistreatment in Lebanon, the framework of the incidents, and the extent of students’ knowledge on mistreatment characteristics.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study conducted using an online-based survey among medical students who have performed clinical rotations in Lebanon.

Results: Out of 300 respondents, 48.7% reported being subjected to mistreatment during clinical practice, which was significantly associated with gender, type of university, and family income. The two most common sources of mistreatment were patients and their families/friends (77.4%), and attending physicians (52.7%), followed by residents (49.3%). Students mostly chose to be passive and pacifying. Additionally, 64.7% of students stated they were not trained about the ideal way to handle these incidents.

Conclusion: This study showed that medical student mistreatment is highly prevalent in Lebanon. It also highlighted the lack of proper education on mistreatment characteristics and the necessity for investigating its effects.

Introduction

As a major part of a physician’s education, the World Federation of Medical Education (WFME) considers Clinical skills acquired from clinical facilities one of the seven criteria for establishing a high-quality medical school [1]. The interaction between patient and student-mentor relationship helps medical students in develop their essential skills of diagnosis, communication, and professionalism.

Unfortunately, medical students are subject to mistreatment during clinical rotations from different sources. The Association of American Medical Colleges defines mistreatment, as a behavior that shows disrespect for the dignity of others and unreasonably interferes with the learning process. It includes many domains such as physical mistreatment, abusive language, sexual harassment, discrimination, and others [2–6].

One source of mistreatment is the medical educators who heavily rely on asking students provocative questions, hoping that this will the concepts in their minds [7]. Many educators, however, take this method to the extreme, resulting in belittlement and mistreatment incidents. Additionally, patients and their families are another source of mistreatment. Patients may feel uncomfortable with training students getting in contact with them or getting involved in their care. This feeling may be due to underestimation of the role of clinical exposure in developing students’ medical competencies and a lack of trust in them.

Students’ mistreatment can be affected by many factors, such as educational background, culture, and socioeconomic status. Mistreatment has a multitude of negative effects on students’ psychology and personalities, since multiple studies have established an association with depression, desire to drop out of school, low career satisfaction, decreased confidence in clinical abilities, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, increased burnout, alcohol abuse, and suicidality [8–14]. Moreover, medical student mistreatment can negatively impact the patient outcomes [15].

Several studies aimed to determine the prevalence of medical students' mistreatment worldwide. A meta-analysis was conducted on 51 studies addressing harassment and discrimination in medical training and revealed that 59.4% of medical residents reported experiencing at least one form of harassment or discrimination during their training, with attending physicians being the most commonly cited source (34.4%) and patients or their families, the second most common (21.9%) [16]. Another study conducted in the United States reported that 15% of mistreatment occurred among pediatric residents, 67% of which originated from patients’ families [17]. Regrettably, 50% of the mistreated residents did not know how to respond to the situation, and 25% of them did not believe any action would be taken by the hospital leadership if they had reported the incident [17].

Little data is present about the prevalence of mistreatment of medical students in the Mediterranean region, with a complete lack of data in Lebanon. Thus, a study about the prevalence of medical students' mistreatment and the extent of students’ knowledge on the proper way to handle it is essential to efficiently manage this issue.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a descriptive, survey-based, cross-sectional study conducted across medical schools in Lebanon. The population included medical students in Lebanon who had been exposed to clinical rotations. There were no exclusion criteria. The survey was distributed online using a snowball sampling method among all medical students in Lebanon. The calculated sample size was determined to be a minimum of 292 for a 95% confidence interval with a 5% margin of error. The sample size was calculated based on an estimation of 1,212 clerkship students enrolled at the eight Faculties of Medicine in Lebanon [18].

Settings

A self-administered survey was adopted from previous studies and adjusted to meet the study objectives [19]. The survey was piloted on 20 students to assess questions comprehension and integrity of the questions. The survey was designed using Google Forms and distributed using snowball technique to medical students. It was divided into four parts. The first part was about sociodemographic information of the students. The second part was about the prevalence of mistreatment among students. The third part was about the characteristics of mistreatment episode by patients or their families/friends. The fourth part was about students’ knowledge of mistreatment characteristics. The survey contained 35 questions and took about 10 min to complete.

Ethical Aspects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beirut Arab University under the number 0113-M-R-0495. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki on the conduct of human research. All data collected were de-identified, gathered, and checked by the principal investigator. The adopted consent form follows the university IRB requirements. This research study is considered to be of minimal risk; the risks associated with this study are the same as those participants face every day.

Patient and Public Involvement Statement

A pilot study was conducted to identify medical students' exposure to mistreatment and the survey questions’ validity and comprehensibility. Otherwise, participants were not involved in the study’s conceptualization.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, version 25) was used for data entry, cleaning, management, and analyses. Descriptive analyses were carried out by calculating the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and numbers and percentages for categorical ones. Inferential statistics, mainly bivariate analyses, were carried out by using the Chi-square test for categorical variables, and associations were measured using Crammer’s V test. A Crammer’s V coefficient: between 0 and 0.1 was considered negligible, between 0.1 and 0.2 weak, between 0.2 and 0.4 moderate, between 0.4 and 0.6 relatively strong, between 0.6 and 0.8 strong, and between 0.8 and 1 very strong. When applicable, Fisher’s exact test was used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

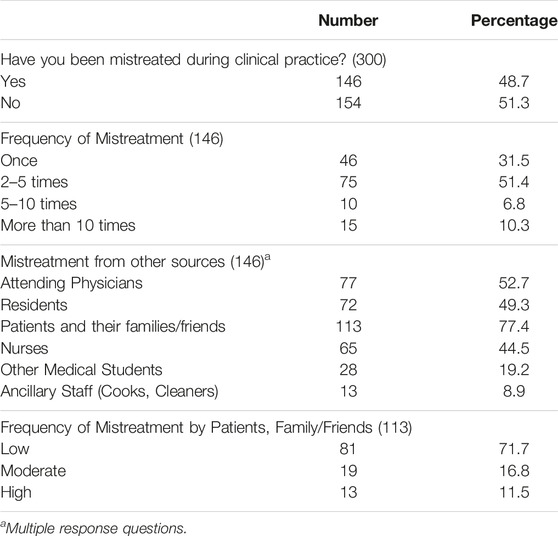

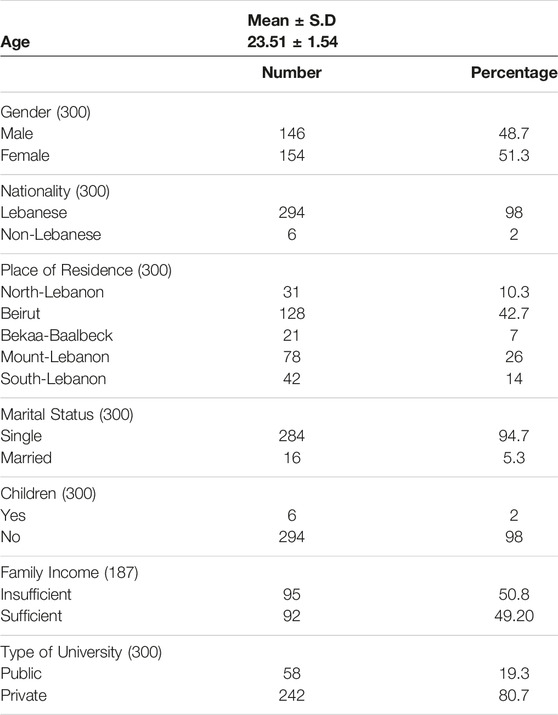

A total of 300 participants responded to the survey, with a mean age of 23.51 ± 1.54. The majority were Lebanese, single, and had no children, and 51.3% were females. Participants were mainly living in Beirut (42.7%) and were enrolled in private universities (80.7%), with half of them reporting an insufficient family income (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic information of participants S.D: Standard Deviation (Beirut, Lebanon. 2024).

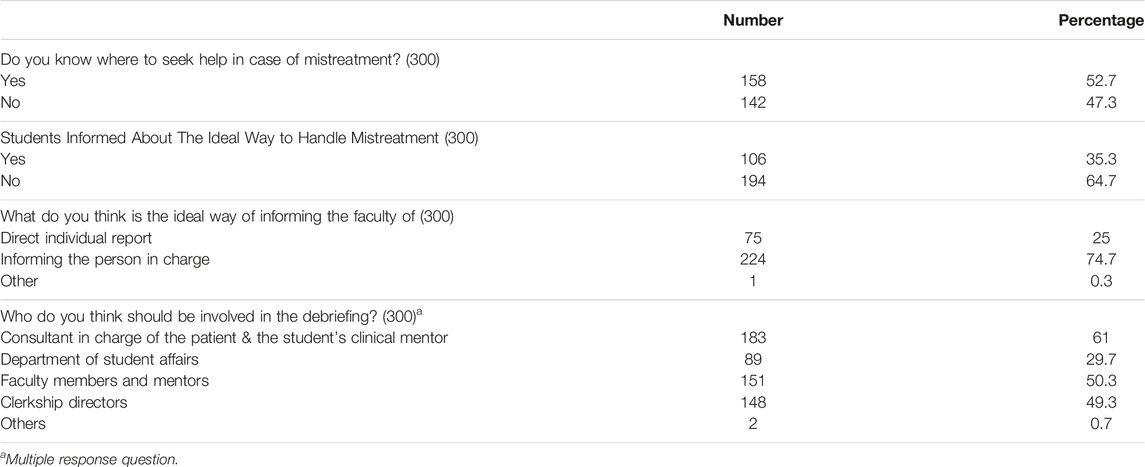

Mistreatment Prevalence and Sources

The prevalence of students’ mistreatment during their clinical practice was 48.7%, with 51.4% of participants stating that they faced a form of mistreatment at least 2–5 times and 6.8% at least 5–10 times. The most common sources of mistreatment reported were patients and their families/friends (77.4%) followed by attending physicians (52.7%) and residents (49.3%) (Table 2).

Mistreatment Incident Characteristics

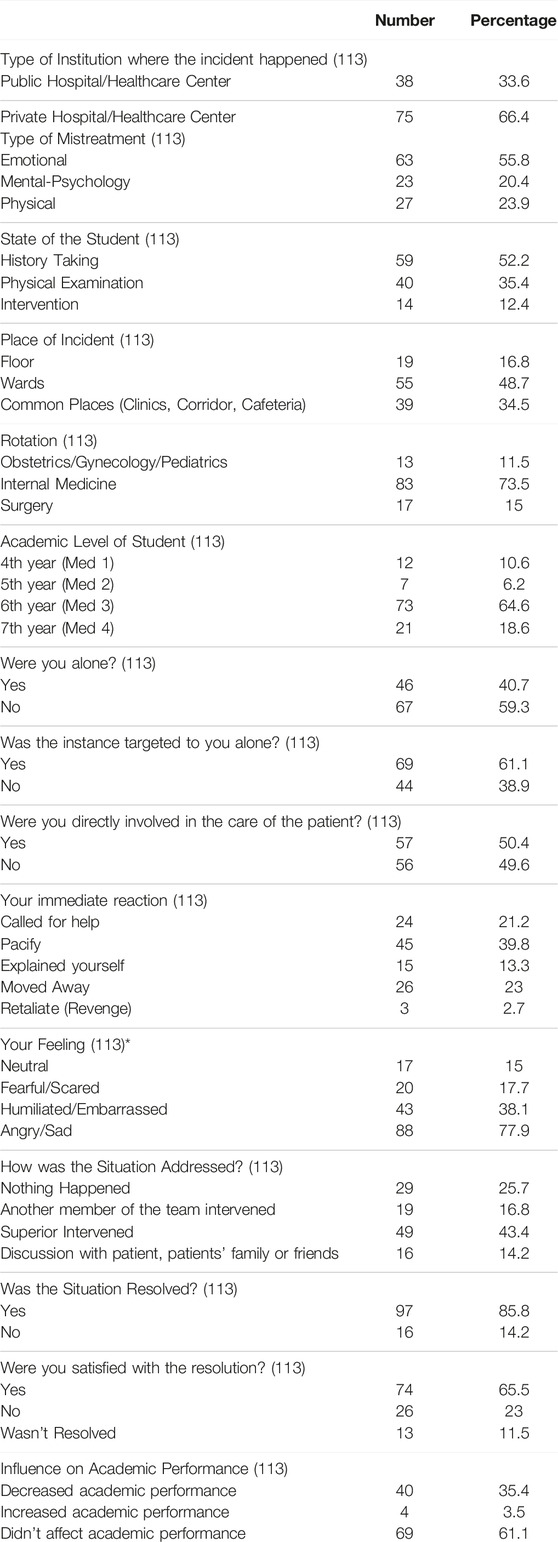

The majority of instances occurred in private hospitals/healthcare centers (66.4%), with almost half of them taking place in wards (48.7%). Last year’s medical students were more exposed to mistreatment (64.6%), and around three-quarters of occurrences were during internal medicine rotations. The incidents happened mostly during history taking (52.2%) and mainly were classified as emotional mistreatment (55.8%). The incident happened mainly when students were alone (40.7%). When asking participants about how they dealt with the incidents, 39.8% of the mistreated students chose to pacify themselves, and 77.9% reported feeling angry or sad. Regarding the way the situations were addressed, a superior intervened in 43.4% of the instances. Most of the cases were resolved (85.8%), and students were mostly satisfied with the resolutions (65.5%). While the majority of students claimed the incidents did not affect their academic performance (61.1%), 35.4% said the incident had a negative impact on their academic performance (Table 3).

Table 3. Information about mistreatment incident from patients, families/friends (Beirut, Lebanon. 2024).

Association Between Mistreatment and Socio-Demographics of Medical Students

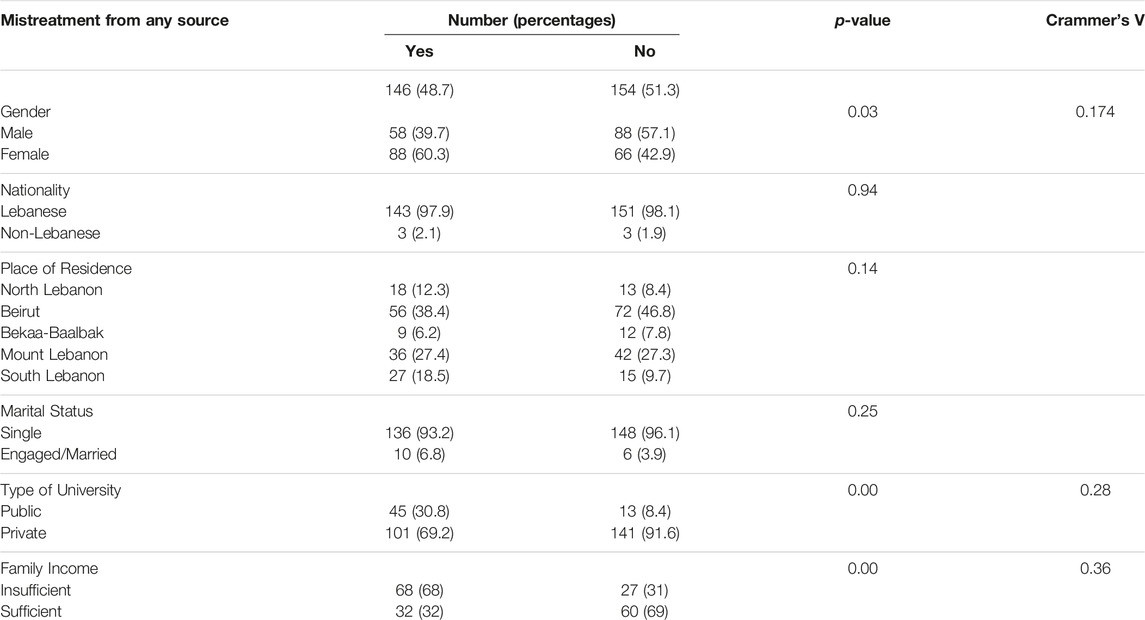

There was a significant association between mistreatment in the clinical setting and gender, type of university, and family income. Although females reported a higher incidence of mistreatment, the association was weak (p = 0.03, φc = 0.17). However, a moderate association was observed between mistreatment incidents and type of university, where students from private institutions reporting a higher incidence of mistreatment than those from the public institution (p = 0.00, φc = 0.28). Similarly, students who reported having insufficient income were more likely to experience mistreatment (p = 0.00, φc = 0.36). On the other hand, there was no association with nationality, place of residence, or marital status (Table 4).

Table 4. Association between mistreatment and socio-demographics of medical students (Beirut, Lebanon. 2024).

Knowledge of Students About Managing Mistreatment

More than half of the participants declared they did not know where to seek help in cases of mistreatment, and 64.7% said they were not informed about the ideal way to handle such instances. Three-quarters of the students believed that the person in charge should be informed; the remainder preferred filing an individual report. 61% believed the consultant in charge of the patient and the student’s clinical mentor should be involved in the debriefing while 50.3% stated the faculty members and mentors to be the best choice (Table 5).

Discussion

Medical students form the backbone of our future healthcare system; yet, literature concerning students’ mistreatment during clinical rotations in the Middle East region remains sparse. The purpose of this study is to assess the prevalence of students’ mistreatment and the knowledge of our students on mistreatment characteristics.

Half of the students reported being mistreated, which is much higher than in some regional and Western countries, particularly those with a robust healthcare infrastructure, such as Saudi Arabia (28%) [20], Turkey (36%) [21], and the United States of America (35.4%) [22]. However, higher rates were reported in Egypt (71.1%) probably due to many cultural and demographic factors [23].

Although teaching in medical school is predominantly confrontational, educators can easily come across as abusive and disparaging [24]. This is a consistent finding in many countries around the world such as Canada, Pakistan, and Chile [25–27], and also was reported in our study. This study also highlighted a major source of mistreatment by patients and their families/friends which were highly prevalent (77.4%), in comparison to other countries like Singapore (14.3%) for example [19]. Most of these incidents occurred during history taking and mainly took place during internal medicine rotations, particularly in wards which may be due to a high level of student-patient interaction.

In comparison to other studies, medical students in their senior years fell victim to more offenses, likely due to increased time they spent in the clinical setting [19]. More than half of the medical students were reported to be directly involved in patient care, which reinforces the notion that the patients and their families perceive the medical students as being incompetent, less experienced, and less skilled in handling their care.

Regarding students’ emotions, the majority of them felt angry/sad, yet around 15% of them felt neutral. This may be due to either students having been immunized or used to it, or students not caring about patients' perception, the latter being alarming. Most of the mistreated students, pacified themselves and did nothing, and only 21.2% decided to call for help, reflecting a lack of knowledge about handling techniques during these situations or the presence of intimidating barriers preventing students from standing up for their rights. An alarming sign is that 2.7% of victims chose to retaliate, which is capable of creating a dangerous situation of tension in which the patient’s wellbeing is at risk. While most of the students claimed that this incident did not affect their academic performance, 35.4% claimed it decreased their academic performance. Further studies, however, are required to assess the impact of these offenses on their mental wellbeing.

Females were subjected to more mistreatment incidents, probably because our society is so used to men dominating STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) [28, 29]. The majority of mistreated individuals were enrolled in private universities, most of which are affiliated with private hospitals in which patients covered directly or indirectly (through medical insurance) their medical expenses, thus tolerated less student involvement in their medical care.

The majority of participants were not trained about mistreatment incidents or characteristics, and 47.3% of them did not know where to seek help. These results show the need for faculties and hospitals to spread awareness among medical students about the proper handling of such situations.

While mistreatment as some participants suggested, is bound to happen and unavoidable, it is essential to also clear up any misconceptions or discomfort patients may have about training medical students involved in their care [30, 31]. Most of the students believed reporting to the person in charge is the ideal action to take, especially if the insults come from patients. However, most of the students might not be eager to blow the whistle to avoid any harm when educators (attending physicians and residents) were the offenders. The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) distributes a Graduation Questionnaire that contains a dedicated section to collect feedback about their experiences during medical school and their clinical practice [32]. Providing medical students with such an anonymous survey at the end of each course is an important way to tackle this issue. It not only reassures students about the protection of their identity but also is an effective way of collecting reports about mistreatment incidents and their effect on students’ wellbeing.

Multiple studies have suggested that medical student mistreatment has been associated with stress, depression, suicidality, and alcohol binge drinking [9, 24]. Repeated encounters with such mistreatment may spike anxiety and emotional distress, which may affect the future performance of students [9]. It also diminishes students’ enthusiasm for learning the curriculum, which decreases the knowledge that students acquire by the end of their education, negatively impacting patients’ outcomes down the line [9].

Conclusion

Medical student mistreatment is highly prevalent in Lebanon, with patients, and educators (attending physicians and residents) being the most significant sources. Such mistreatment has a significant impact on students and further studies are required to measure the extent of this impact on their mental health.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study; therefore, no causalities can inferred. Recall bias may be present due to the data collection procedure. There is no information about the severity of mistreatment and how students define and classify mistreatment.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional review board of Beirut Arab University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AEN, AEY, YA, SE, AA, ZA, HE, MA, GA, MH, and BA contributed to the study conception, study design, proposal development, and oversight of data collection, data entry, data review and writing of manuscript. GA contributed in data collection, entry and analysis. AEN, MH, and BA contributed to data analysis, interpretation for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare(s) that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. World Federation for Medical Education. Criteria for a New Medical School. Geneva, Switzerland: World Federation for Medical Education (2020).

2. Bursch, B, Fried, JM, Wimmers, PF, Cook, IA, Baillie, S, Zackson, H, et al. Relationship Between Medical Student Perceptions of Mistreatment and Mistreatment Sensitivity. Med Teach (2012) 35:e998–1002. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.733455

3. Heru, A, Gagne, G, and Strong, D. Medical Student Mistreatment Results in Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress. Acad Psychiatry (2009) 33(4):302–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.302

4. Richman, JA, Flaherty, JA, Rospend, KM, and Christensen, ML. Mental Health Consequences and Correlates of Reported Medical Student Abuse. JAMA (1992) 267(5):692–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480050096032

5. Frank, E, Carrera, JS, Stratton, T, Bickel, J, and Nora, LM. Experiences of Belittlement and Harassment and Their Correlates Among Medical Students in the United States: Longitudinal Survey. BMJ (2006) 333:682–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C

6. Baldwin, DC, Daugherty, SR, and Eckenfels, EJ. Student Perceptions of Mistreatment and Harassment During Medical School. A Survey of Ten United States Schools. West J Med (1991) 155:140–5.

7. Stoddard, H, and O'Dell, D. Would Socrates Have Actually Used the "Socratic Method" for Clinical Teaching? J Gen Intern Med (2016) 31:1092–6. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3722-2

8. Koh, GC, Wong, TY, Cheong, SK, Lim, EC, Seet, RC, Tang, WE, et al. Acceptability of Medical Students by Patients From Private and Public Family Practices and Specialist Outpatient Clinics. Ann Acad Med Singap (2010) 39:555–64. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.v39n7p555

9. Frank, E, Carrera, J, Stratton, T, Bickel, J, and Nora, L. Experiences of Belittlement and Harassment and Their Correlates Among Medical Students in the United States: Longitudinal Survey. BMJ (2006) 333:682. doi:10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C

10. Stratton, TD, McLaughlin, MA, Witte, FM, Fosson, SE, and Nora, LM. Does Students' Exposure to Gender Discrimination and Sexual Harassment in Medical School Affect Specialty Choice and Residency Program Selection? Acad Med (2005) 80:400–8. doi:10.1097/00001888-200504000-00020

11. Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: All Schools Summary Report (2012). Available from: https://www.aamc.org/media/55736/download (Accessed January 31, 2014).

12. Cook, AF, Arora, VM, Rasinski, KA, Curlin, FA, and Yoon, JD. The Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment and Its Association With Burnout. Acad Med (2014) 89(5):749–54. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000204

13. Schuchert, MK. The Relationship Between Verbal Abuse of Medical Students and Their Confidence in Their Clinical Abilities. Acad Med (1998) 73:907–9. doi:10.1097/00001888-199808000-00018

14. Heru, A, Gagne, G, and Strong, D. Medical Student Mistreatment Results in Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress. Acad Psychiatry (2009) 33:302–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.302

15. Mazer, L, Bereknyei Merrell, S, Hasty, B, Stave, C, and Lau, J. Assessment of Programs Aimed to Decrease or Prevent Mistreatment of Medical Trainees. JAMA Netw Open (2018) 1:e180870. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0870

16. Fnais, N, Soobiah, C, Chen, MH, Lillie, E, Perrier, L, Tashkhandi, M, et al. Harassment and Discrimination in Medical Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad Med (2014) 89:817–27. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200

17. Whitgob, EE, Blankenburg, RL, and Bogetz, AL. The Discriminatory Patient and Family: Strategies to Address Discrimination Towards Trainees. Acad Med (2016) 91:S64–S69. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001357

18. Nemr, E, Yazigi, A, Nemr, R, and Meskawi, M. Undergraduate Medical Education in Lebanon. Med Teach (2012) 34:879–82. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.716184

19. Zhu, G, and Tan, TK. Medical Student Mistreatment by Patients in the Clinical Environment: Prevalence and Management. Singapore Med J (2019) 60(7):353–8. doi:10.11622/smedj.2019075

20. Alzahrani, HA. Bullying Among Medical Students in a Saudi Medical School. BMC Res Notes (2012) 5:335. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-5-335

21. Ince, A, Jadoo, SAA, and Torun, P. Workplace Violence Against Medical Students- A Turkish Perspective. J Ideas Health (2019) 2:70–4. doi:10.47108/jidhealth.Vol2.Iss1.12

22. Hill, KA, Samuels, EA, Gross, CP, Desai, MM, Sitkin Zelin, N, Latimore, D, et al. Assessment of the Prevalence of Medical Student Mistreatment by SEX, Race/Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation. Jama Intern Med (2020) 180:653–65. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030

23. Elghazally, NM, and Atallah, AO. Bullying Among Undergraduate Medical Students at Tanta University, Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Study. Libyan J Med (2020) 15(1):1816045. doi:10.1080/19932820.2020.1816045

24. Major, A. To Bully and Be Bullied: Harassment and Mistreatment in Medical Education. AMA J Ethics (2014) 16(3):155–60. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2014.16.03.fred1-1403

25. Lu, K, and Schellenberg, J. Medical Students Applaud World Medical Association Statement on Bullying and Harassment Within the Profession (2017). Available from: https://www.cfms.org/news/2017/10/31/medical-students-applaud-world-medical-association-statement-on-bullying-and-harassment-within-the-profession.html (Accessed April 29, 2021).

26. Mukhtar, F, Daud, S, Manzoor, I, Amjad, I, Saeed, K, Naeem, M, et al. Bullying of Medical Students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak (2010) 20(12):814–8.

27. Maida, AM, Vásquez, A, Herskovic, V, Calderón, JL, Jacard, M, Pereira, A, et al. A Report on Student Abuse During Medical Training. Med Teach (2003) 25(5):497–501. doi:10.1080/01421590310001606317

28. AAUW. The Stem GAP: Women and Girls in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math – AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881 (2020). Available from: https://www.aauw.org/resources/research/the-stem-gap/ (Accessed April 16, 2021).

29. Searing, L. The Big Number: Women Now Outnumber Men in Medical Schools (2019). Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/the-big-number-women-now-outnumber-men-in-medical-schools/2019/12/20/8b9eddea-2277-11ea-bed5-880264cc91a9_story.html (Accessed April 16, 2021).

30. Rubliauskas, K, Šalkauskaitė, A, and Macas, A. Patient Feedback on Medical Students in Tertiary Health Care: Are Medical Students Accepted in Clinical Practice? Acta Med Litu (2019) 26:107–12. doi:10.6001/actamedica.v26i1.3963

31. Al-Khatib, T, Othman, S, and El-Deek, B. Patients' Perception Toward Medical Students' Involvement in Their Surgical Care: Single Center Study. Edu Res Int (2016) 2016:8234841. doi:10.1155/2016/8234841

Keywords: student mistreatment, prevalence, Lebanon, mistreatment characteristics, patients

Citation: El Nouiri A, El Kassem S, Al Maaz Z, Alhajj Y, Al Moussawi A, El Yaman A, El Hajjar H, Abdallah M, Assi G, Houri M and Azakir B (2024) Prevalence and Characteristics of Medical Student Mistreatment in Lebanon. Int J Public Health 69:1606710. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2024.1606710

Received: 13 October 2023; Accepted: 31 May 2024;

Published: 04 July 2024.

Edited by:

Nino Kuenzli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), SwitzerlandCopyright © 2024 El Nouiri, El Kassem, Al Maaz, Alhajj, Al Moussawi, El Yaman, El Hajjar, Abdallah, Assi, Houri and Azakir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bilal Azakir, Yi5hemFraXJAYmF1LmVkdS5sYg==

Ahmad El Nouiri1

Ahmad El Nouiri1 Bilal Azakir

Bilal Azakir