- 1National Center for Global Health, National Institute of Health (ISS), Rome, Italy

- 2Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome, Roma, Italy

- 3Italian Society of Migration Medicine (SIMM), Rome, Italy

- 4Prolepsis Institute for Preventive Medicine and Environmental and Occupational Health, Marousi, Greece

Objectives: Access to vaccination for newly arrived migrants (NAMs) is a relevant concern that requires urgent attention in EU/EEA countries. This study aimed to develop a General Conceptual Framework (GCF) for understanding how to improve vaccination coverage for NAMs, by characterizing and critically analyzing system barriers and possible strategies to increase vaccination.

Methods: A theoretical conceptualization of the GCF was hypothesized based on conceptual hubs in the immunization process. Barriers and solutions were identified through a non-systematic desktop literature review and qualitative research. The GCF guided the activities and facilitated the integration of results, thereby enriching the GCF with content.

Results: The study explores the vaccination of NAMs and proposes strategies to overcome barriers in their vaccination process. It introduces a framework called GCF, which consists of five interconnected steps: entitlement, reachability, adherence, achievement, and evaluation of vaccination. The study also presents barriers and solutions identified through literature review and qualitative research, along with strategies to enhance professionals’ knowledge, improve reachability, promote adherence, achieve vaccination coverage, and evaluate interventions. The study concludes by recommending strategies such as proximity, provider training, a migrant-sensitive approach, and data collection to improve vaccination outcomes for NAMs.

Conclusion: Ensuring equitable access to healthcare services, including vaccination, is crucial not only from a humanitarian perspective but also for the overall public health of these countries.

Introduction

Access to immunization for migrants, especially for newly arrived migrants (NAMs) is a critical aspect of public health interventions in the European Union and Economic European Area (EU/EEA) [1]. Immunization is a key global health intervention that saves millions of lives and prevents the spread of numerous life-threatening diseases [1].

Migrants may not be immunized or may be under immunized in their countries of origin and so may be vulnerable to acquire Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPD). Scientific evidence strongly supports the importance of vaccinations for protecting migrant populations from infectious diseases. Migrants are at higher risk due to unsanitary conditions and limited access to healthcare. Vaccinations are an effective way to prevent the spread of diseases among migrant populations, ensuring their health and the health of the communities they join. Access to immunization services for migrants is crucial for preventing disease outbreaks and promoting their wellbeing and integration into society [2–5]. In the WHO European region, migrants and refugee children constitute about 25% of the total migrant population, making them one of the groups most at risk for vaccine-preventable diseases [6].

In 2019, the WHO published a technical guide outlining three essential elements to ensure high vaccination coverage among refugees and migrants: appropriate vaccination services for newly arrived individuals, delivery of immunization services as part of mainstream health services, and targeted and culturally appropriate immunization services [4]. Moreover, in 2020, all WHO member states endorsed the Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind (IA2030) [7]. This agenda is organized into seven strategic priorities for immunization in the next decade and is guided by four core principles: people-centered, country-owned, partnership, and data-guided. National and international public health institutions have developed strategies to address the immunization of migrants in their national health systems, despite these efforts, challenges remain in ensuring optimal vaccination coverage for this vulnerable population [2–5]. To further address this issue, the EU has also launched funding opportunities such as the Access to Vaccination for Newly Arrived Migrants (AcToVax4NAM) project, which intends to improve vaccination literacy (VL) and access and thereby vaccination coverage for NAMs in first-line and destination countries making access conditions more equitable and guaranteed [8].

This study aims to develop a General Conceptual Framework (GCF) to understand how to improve vaccination coverage among migrants in EU/EEA countries. Considering all steps taken in the healthcare pathway from the vaccination entitlement to completion of needed vaccination, addressing also dropout, and adopting a life-course approach to immunization for children, adolescents, adults and elderly. By reviewing existing policies, strategies, and initiatives, including those from the WHO and EU-funded projects, the GCF identifies system barriers and best strategies as well as potential areas for improvement to ensure equitable access to vaccination for all, including NAMs. In doing so, we hope to contribute to the ongoing efforts to achieve universal health coverage and protect public health across EU countries.

Methods

The GCF was developed through three steps, using mixed-methods: theoretical conceptualization of a Preliminary Conceptual Framework (PCF), non-systematic desktop review and qualitative research (focus groups and personal interviews) and consolidation of the GCF.

Theoretical Conceptualization of a PCF—Step 1

As first step, the extended expertise on migrant health and immunization systems of the National Center for Global Health, Istituto Superiore di Sanità and the Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, Sapienza University of Rome staff was used as key resource to conceptualize, identify and design the logical process of an inclusive immunization program for NAMs. The development of the PCF started with a hub-and-spoke model during a hybrid (in-person and virtual) workshop. Furthermore, to be able to frame the different issues and understand the reasoning behind each hub, the team has formulated specific “Question Groups” (QG) concerning every hub. All questions refer to NAMs according to the AcToVax4NAM operational definition “A person (with a different citizenship from the hosting country, with either EU/EEA or third country citizenship), who entered the country in the last 12 months EITHER within the procedures prescribed by the governmental migration policies, excluding tourists and short visa/permit <3 months, OR outside the procedures recognized by the legislation (or overstay after visa expired)” and for all questions, distinctions between different legal status of NAMs should be considered. These questions were a useful tool to accurately guide personal interviews/focus groups and characterize and assign all records extracted from the literature review and the qualitative research in the corresponding hub (see Supplementary Material S1).

Non-Systematic Desktop Review and Qualitative Research—Step 2

Non-Systematic Desktop Review

A desktop literature review has been implemented, also at country level, to identify existing research concerning system barriers (at legal, economic, organizational, psycho-social and cultural-linguistic level) and solutions, recommended or suggested, to overcome them. A search strategy was launched on PubMed in order to find scientific articles or documents concerning the topic of interest. The consortium countries integrated the search with materials in local language or contained in national websites (Scientific literature, Guidance, Guideline, Bulletin, Report, Legislation, Policy document, Standard operating procedure). The Supplementary Material contains full details of the search strategy including inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Supplementary Material S2).

Qualitative Research (Focus Groups and Personal Interviews)

Focus groups (FGs) and Personal Interviews (PIs) were conducted in Germany, Poland, Spain, Italy, Greece, Malta, and Cyprus, partners of AcToVax4NAM consortium, in order to understand the actual experiences of the “professionals FOR health” (all professionals who must/can deal with the health of migrants) involved in NAMs immunization and to achieve the characterization of system barriers (legal, economic, organizational, psycho-social and cultural-linguistic) and identification of possible and sustainable solutions at country level. Eligible participants included: 1) health and social care professionals who work in the field of delivery of immunizations, 2) professionals, who work in managing/organizing immunization services, and 3) experts related to immunization planning. Guidelines for performing FGs discussion and PIs were developed for all partners by Prolepsis Institute to provide a common methodology and ensure a uniform group composition (see Supplementary Material S3). FGs discussions and PIs were transcribed verbatim in local languages and identifiers were removed to maintain the anonymity of participants. Transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis [9].

Integration of Results and Consolidation of the GCF—Step 3

The GCF and the QGs were utilized to determine and merge the barriers and solutions found during the reading of the desktop literature review and the thematic analysis of the qualitative research. This selection and combination process was guided by their similarities. Subsequently the partners, especially the members of the AcToVax4NAM Steering Committee whichcomprises the project manager and the 6 WP leaders and is the key decision-making and issue-resolution body for the project, sent a two-round of suggestions and comments according to the AcToVax4NAM evaluation plan. These were used for a further revision of the findings, which was then presented to the project Steering Committee meeting and finalized by the end of June 2022.

Results

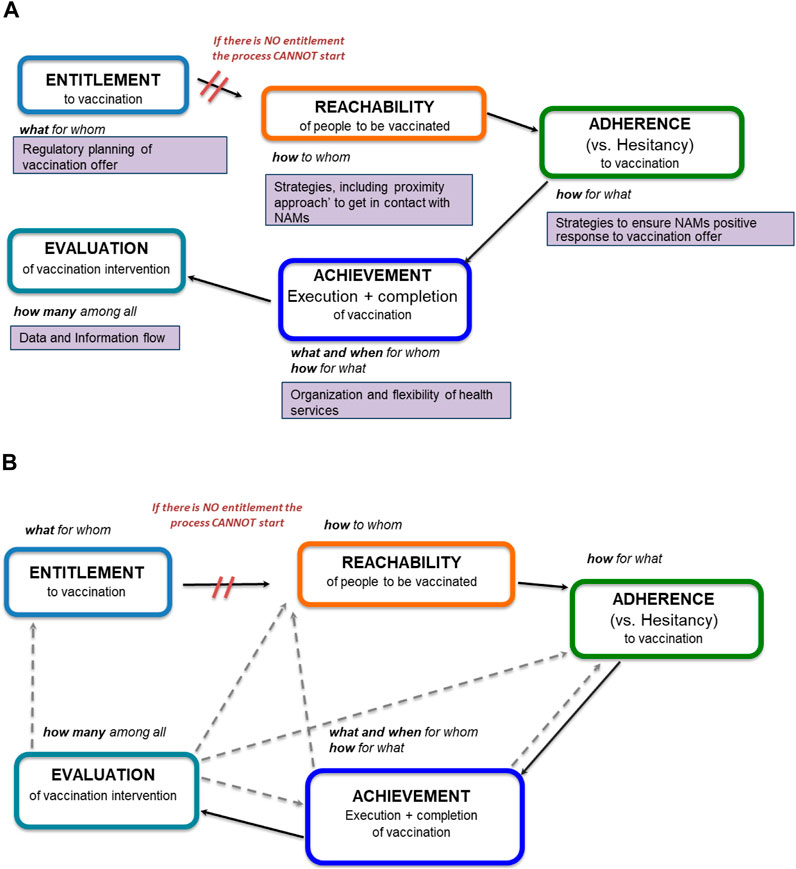

The logical conceptualization considered the main steps involved in the vaccination of NAMs. These steps become the five hubs of the Preliminary Conceptual Framework: 1) Entitlement to vaccination, 2) Reachability of people to be vaccinated, 3) Adherence (vs. Hesitancy) to vaccination, 4) Achievement of vaccination (execution and completion), 5) Evaluation of vaccination intervention (Figures 1A, B). As can be seen, there is a connection between each hub. The interrupted arrow starting from the Entitlement hub underlines that without the legal right to immunisation the entire process cannot start. The continuous arrows show the sequential continuity of the process.

Entitlement intended to encapsulate “what for whom” and concerns the regulatory planning of the vaccination offer; Reachability is related to “how to whom” and regards all strategies, including the “proximity approach,” and abilities of the health service to get in contact with NAMs; Adherence that framed “how for what” includes the strategies to ensure that NAMs respond positively to the vaccination offer and to devise abilities in the “professional FOR health” to counteract vaccination hesitancy and fear among NAMs; Achievement concerns the execution and completion of vaccination, that is “what (vaccines) and when for whom and how for what” and should depends on organization and flexibility of health services; Evaluation, which should report “how many (vaccinated) among all migrants,” regards the necessity of data collection and information flow about NAMs vaccination to be used for the evaluation of activities (Figure 1A).

The dashed arrows in Figure 1B underline that the Achievement and Evaluation are linked with the other hubs. In particular, the dashed arrows starting from the Achievement hub indicate that if the execution and completion of vaccination do not happen it is important to go back to the previous hubs (Reachability and Adherence) to understand the reasons. The dashed arrows from the Evaluation hub indicate that the evaluation process must be cross-cutting at all hubs and has to take into account their strategies and actions.

Barriers and Solutions From Literature Review

One-hundred and fifty-one documents were collected from the review, 85 documents (out of which 38 scientific articles, 16 reports, 5 guidelines, 4 policy documents, 5 technical documents, and 17 other document types), containing at least one barrier and/or solution, were selected and analyzed. After the exclusion of 7 documents (not pertinent to immunization), 78 documents were included [10–20], [21–26], [5,27–33], [2,34–40], [41–79], [4,80–83]. From them, 403 records were extracted, containing barriers (210 records) and possible solutions (193 records). The table in Supplementary Material S3 reports a list of references where at least a barrier and/or a solution related to specific hub can be found.

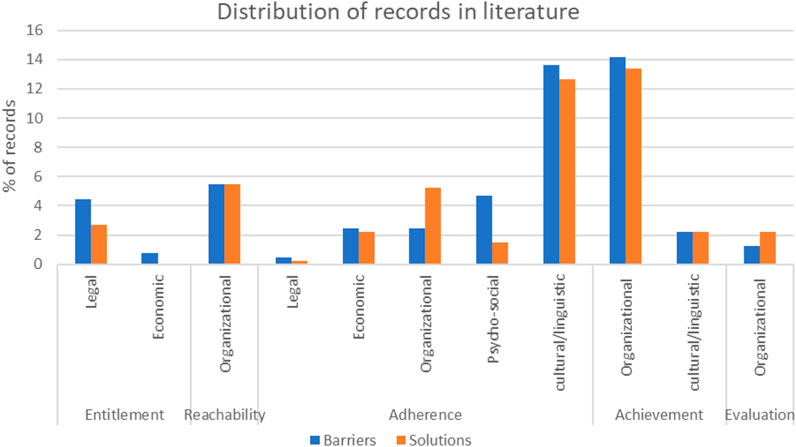

By using the QGs, each record was characterized in barriers (52.1%) and solutions (47.1%) and then assigned to related sub-categories. A total number of 32 records were assigned to Entitlement, including legal barriers (4.5%) and solutions (2.7%), economic barriers (2.7%) while no economic solutions were found; 44 records were assigned to Reachability, including organizational barriers (5.5%) and solutions (5.5%); 184 records were assigned to Adherence, including legal barriers (0.5%) and solutions (0.2%), economic barriers (2.5%) and solutions (2.2%), organizational barriers (2.5%) and solutions (5.2%), psycho-social barriers (4.7%) and solutions (1.5%) and cultural/linguistic barriers (13.6%) and solutions (12.7%); 129 records were assigned to Achievement, including organizational barriers (14.1%) and solutions (13.4%), cultural/linguistic barriers (2.2%) and solutions (2.2%) and 14 records to Evaluation, including organisational barriers (1.2%) and solutions (2.2%) (Figure 2).

Qualitative Research Findings: Descriptive Characteristics of Participants

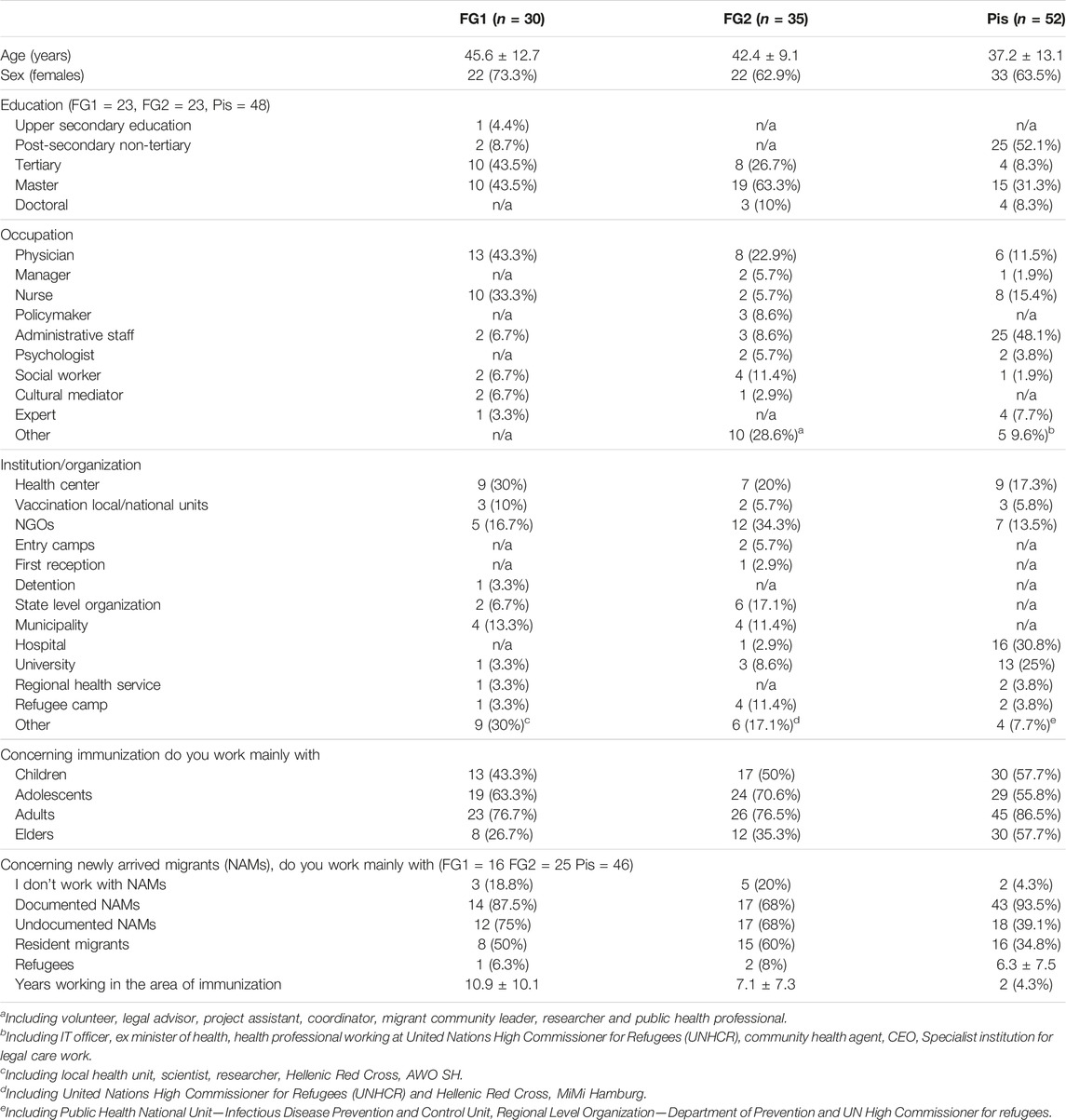

In total, 117 people participated in 13 FGs and 53 PIs in Germany, Poland, Spain, Italy, Greece, Malta, and Cyprus. Demographic characteristics of health and social care professionals are showed in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Demographic characteristics of health and social care professionals who work in the field of delivery of immunizations (Focus Group 1—FG1), health and social care professionals working in the management/organization of immunization services for minors and/or adult migrants. (Focus Group 2—FG2) and experts related to immunization planning (Personal Interviews—Pis.), EU/EEA, 2022.

Integration of Results and Consolidation of the GCF

The methodology that involved the integration of different research tools (desktop literature review, focus group, personal interview) into the Preliminary Conceptual Framework permitted a deepening of the processes related to the theoretical conceptual schema produced. The integrated analysis of the findings produced a “fill-in” of the conceptual hubs, previously identified in a theoretical way, producing a greater amplitude, depth and complexity of the dynamics that link the logical hubs of the NAMs vaccination process. In particular, there was a focus on the barriers and solutions that both the literature and the qualitative research identified as relevant in the vaccination process with the aim of making the research more linked to day-to-day operations and stressing their problems and deficiencies. Key findings from Desktop Literature Review and Qualitative research (FGs discussions and Pis) are summarized in Supplementary Material S4.

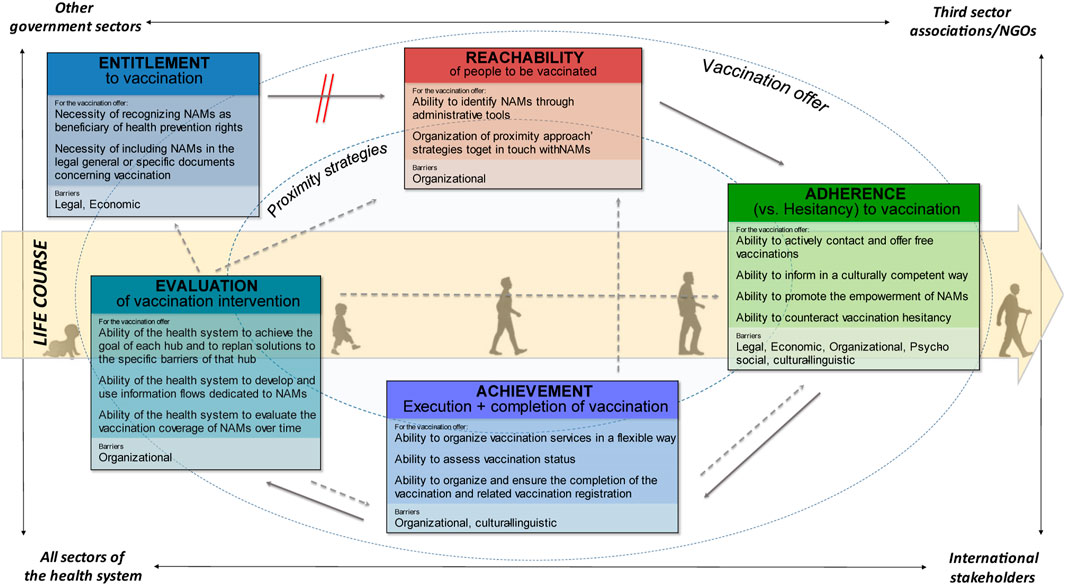

After the PCF has been filled in and critically reviewed with the results of the non-systematic literature review and FGs and Pis, the GCF is no longer just a logical framework, but becomes a pathway that can actually strengthen health systems and make vaccination more guaranteed and equitable. Importantly, we need to move from a neutral reading to a critical re-reading, so that the GCF is no longer just a diagram. Despite the heterogeneity and breadth of the results of the analytical work, an attempt has been made in Figure 3 to graphically summarize the overall picture obtained, integrating some elements with respect to the starting outline.

FIGURE 3. Schematization of the GCF with the specific abilities and barriers of each hub, EU/EEA, 2022.

Health System’s Strategies to Address Vaccination Barriers for NAMs by Hub

Based on literature review and experiences of health professionals, addressing vaccination barriers for migrants requires a comprehensive and multi-faceted approach. This approach should consider various factors and challenges. The following strategies are essential for overcoming system barriers and promoting successful vaccination interventions for migrants.

Entitlement to vaccination—this hub focuses on the rights of NAMs to receive vaccinations and the barriers that may arise in relation to their entitlement.

• Enhancing professional’s knowledge about health rights: Healthcare professionals must be well-informed about migrants’ rights and entitlements to healthcare services. This includes providing continuous training for healthcare personnel and practitioners on the entitlement to health and vaccinations for different profiles of migrants. Furthermore, national, regional, and local authorities should revise their immunisation policies and documents to explicitly mention migrants and NAMs as beneficiaries. This can be done by updating existing documents or creating new ones that clearly state the rights and access to immunisation services for all individuals residing within the country, regardless of their legal status or country of origin.

Reachability of people to be vaccinated—this hub addresses the challenges associated with reaching NAMs and ensuring that they have access to vaccination services. It involves proximity strategies to overcome geographical, logistical, and communication barriers.

• Improving reachability through updated data sources and multi-sector collaboaration: Accurate and up-to-date information about migrant populations is essential for effective outreach. This includes improving data sources by aligning with municipal registers and establishing links between different government departments and the National Health System (NHS). Strengthen cooperation between different levels and sectors, including general practitioners, family paediatricians, clinics for temporarily or undocumented foreigners, family planning units, hospitals, municipalities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and other entities that interact with migrants. Involve foreign communities in reaching out to migrants not listed for vaccination.

Adherence to vaccination—this hub deals with factors that influence the adherence of NAMs to the recommended vaccination schedule. It includes considerations like cultural beliefs, language barriers, vaccine acceptance as well as organizational vaccination literacy.

• Promoting adherence through culturally sensitive health campaigns and strategies: Plan health promotion campaigns specifically targeting migrant populations. Provide training to healthcare professionals, including language mediators, on migrant health needs, cultural awareness, vaccination hesitancy, risk communication, and community engagement. Involve migrant communities in promoting vaccinations. Strengthen links with general practitioners and family paediatricians to promote vaccinations for the entire household. Ensure all services that interact with migrants can provide accurate information on vaccination pathways.

Achievement of vaccination—this hub encompasses the actions needed to successfully administer vaccinations to NAMs, including effective delivery, monitoring, and follow-up. It involves strategies to ensure that the vaccination process is completed for each individual.

• Achieving vaccination coverage through flexible services and better documentation: Develop detailed procedures for the entire vaccination cycle and make them available to vaccine service operators. Improve access to vaccinations by extending days and time slots, facilitating reservation systems, establishing multidisciplinary teams at vaccination centers, setting up local clinics and temporary hubs, and organizing vaccination programs with support from migrant communities and third-sector organizations. Provide necessary support for migrants during the vaccination process, such as linguistic-cultural mediators and information sheets in multiple languages. Enhance communication and relational skills of healthcare professionals in the vaccination field. Facilitate the exchange of vaccine information and certificates between countries, including the availability of vaccination certificates in multiple languages.

Evaluation of the intervention—this is a cross-cutting hub which focuses on assessing the effectiveness of vaccination interventions for NAMs. It involves monitoring and evaluation activities to measure the impact of the implemented strategies and identify areas for improvement.

• Evaluating interventions through research and monitoring: Conduct surveys or focus groups to understand why certain groups do not benefit from vaccination. Monitor and evaluate the system’s ability to reach migrants, including obstacles and determinants. Study vaccine hesitancy and refusal among migrants, including obstacles and determinants. Analyze vaccination coverage for migrants and strengthen cooperation with local registries and government entities to improve data quality. Develop ways to record additional or booster doses for migrants not enrolled in the NHS.

Strategies Common to More Than One Hub

Certain strategies can simultaneously address the purposes of different hubs and fulfill unique purposes concurrently. The following strategic lines encompass multiple hubs:

a) Proximity strategies: public health strategies focus on fostering relationships between public institutions, private social organizations and communities with the goal of promoting access to services. Key features include networking, a multidisciplinary approach, the use of mobile teams, cultural mediators, and raising provider awareness through the active offer of health services, the orientation to services, the creation of pathways for taking in charge and the involvement of the population in empowerment processes. These strategies help to overcome geographical barriers and encourage better access to healthcare for migrants. Proximity strategies inform the vaccination process and are tailored to each hub, characterizing specific actions related to reachability, adherence and achievement.

b) Training courses for providers: the skills and competencies of providers involved in the vaccination process are crucial. Continuous training and updating, are essential for strengthening the health system and other sectors involved in vaccination. In Germany, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) offers a range of training courses and resources for healthcare providers involved in vaccination services. These courses include topics such as vaccination schedules, vaccine storage and handling, and communication skills to effectively engage with diverse populations, including migrants. Training improve the system’s ability to reach NAMs, especially those in the hard-to-reach groups (reachability), offer and promote vaccinations, particularly also in countering vaccination hesitancy (adherence), and carry out vaccinations (achievement). Training is also a key element in developing proximity strategies should involve all stakeholders involved in the vaccination process.

c) Migrant sensitive approach: effective vaccination promotion, organization, and delivery require sensitivity to the unique differences of migrants, including age, gender, legal status, economic status, and more. Investing in multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral training and retraining helps strengthen the migrant-sensitive approach. In the United Kingdom, the NHS has initiated several programs to improve vaccination rates among migrants, such as offering translated materials in various languages, providing cultural competency training for healthcare providers, and using community leaders to promote vaccine uptake.

d) Data source: improving vaccination data collection among migrant populations is critical for developing appropriate health policies and services. Hub-specific Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) can enhance the quality of the vaccination process by facilitating information sharing within systems at various level. Access to disaggregated data enables better estimation of vaccination coverage, strengthens evaluation for each identified hub and improve the vaccination process in that hub. Particularly important is the registration of vaccinations and linking national and supranational databases to address the mobility of migrant populations. In the European Union, the ECDC has developed a project called “Vaccine Schedule” that gathers information on vaccination schedules and policies across EU/EEA countries. This project aims to improve data collection and sharing between countries to better understand vaccination coverage and gaps in migrant populations.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a General Conceptual Framework (GCF) to understand how to improve the vaccination coverage for NAMs in EU/EEA. The GCF can help improve vaccination coverage for NAMs by providing a systematic approach to identifying and addressing barriers throughout the vaccination process. The methods used to identify barriers and solutions in the study were a combination of literature review and qualitative research. The literature review involved analysing relevant publications and categorizing the barriers and solutions into different subcategories. The study examined legal, economic, organizational, psycho-social, and cultural/linguistic barriers and strategies associated with entitlement, reachability, adherence, achievement, and evaluation. Additionally, qualitative research was conducted through focus groups and interviews with health and social care professionals in Germany, Poland, Spain, Italy, Greece, Malta, and Cyprus. These participants provided valuable insights into the implementation of vaccinations for NAMs and contributed to the identification of barriers and potential strategies to overcome them. The findings from both the literature review and qualitative research were used to develop the GCF and inform the recommendations for improving vaccination coverage for NAMs. The five conceptual hubs provide a framework for understanding the different stages and challenges in improving vaccination coverage adopting also a life-course approach to immunization for children, adolescents, adults and elderly.

The framework especially helps in identifying specific barriers and possible strategies at each stage of the vaccination process. For example, it can highlight issues related to entitlement, such as ensuring that healthcare worker understand migrants’ rights to receive vaccinations and have their access to vaccination services [3, 19]. It can also help in addressing challenges related to reachability, such as improving outreach efforts to inform migrants about available vaccinations and locations [4, 81]. Furthermore, the GCF can assist in promoting adherence to vaccination by identifying strategies to overcome language and cultural barriers that may affect vaccine acceptance [17, 74]. It can also support the achievement of vaccination goals by recommending interventions like proximity interventions or organizational flexibility which bring vaccination services closer to migrant communities [47]. In terms of evaluation, the GCF emphasizes the importance of monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of vaccination interventions for NAMs [4]. This allows for continuous improvement and the identification of best practices and approach that can be shared across countries. By implementing these strategies and addressing various barriers, successful vaccination interventions for NAMs can be achieved. This will not only ensure their health and wellbeing but also contribute to the overall health of the communities they live in.

However, the study acknowledges the lack of international agreement on the definition of NAMs, which poses limitations in data collection and in understanding and addressing their specific needs. The AcToVax4NAM project has developed an operational definition of NAM based on public health considerations and guidelines, with the aim to include a wide range of people on the move, regardless of the person’s legal status or country of origin. It takes into account all ages and emphasizes the ability of the healthcare system to assess vaccination status and, if necessary, provide appropriate vaccinations. Although it was developed in a project for NAMs, we have also realized through the literature review and focus groups that the GCF can also be used for migrants who have been in the country for a longer period of time.

The study also calls for collaboration with other European projects to extend consensus on the definition of NAMs and create a greater network among countries. In fact, although the applicability of the GCF may vary across countries due to differences in healthcare systems, definitions of NAMs, and other contextual factors, the framework provides a starting point for addressing vaccination coverage challenges. By comparing the findings of the GCF with relevant literature and adapting it to specific country contexts, policymakers and healthcare providers can tailor their strategies to improve vaccination coverage for NAMs effectively. Based on our extensive literature review, we have found no existing conceptual framework that precisely outlines the vaccination process for NAMs, as illustrated in this study.

This study also suggest to create and adapt SOPs and country specific action-oriented flow-chart by drawing from the 5-hub of the GCF. SOPs should cover all aspects of vaccination and be implemented at the national level by all relevant health services. This will allow all stakeholders involved to know what to do, how to do it and with whom it is important to collaborate, as there is not one-size-fits-all model for national health systems or migrants’ rights. Finally, advocating for migrants’ rights to healthcare and promoting inclusive policies can help create a supportive environment for vaccination efforts. Engaging policymakers, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders can lead to the development of policies that prioritize migrants’ health and wellbeing.

In conclusion, vaccinations play a crucial role for NAMs, as they may be a vulnerable group in need of protection from infectious diseases. During their journey and settlement in a new community, migrants can be exposed to poor hygiene conditions and limited access to medical care, increasing their vulnerability to infectious diseases. Vaccinations represent an effective means to prevent the spread of infectious diseases within migrant populations, protecting not only the migrants themselves but also the host communities. Ensuring that migrants have equal access to immunization services reduces the risk of outbreaks and the spread of diseases within communities. Furthermore, it promotes the wellbeing and integration of migrants, leading to healthier and more inclusive societies. Overall, the GCF developed in this study will serve as a blueprint for each country to develop their own action-oriented flow charts/SOPs based on the specific barriers and proposed strategies identified. The framework will help improve vaccination coverage for NAMs, taking into consideration different NAMs categories, the heterogeneity of settings, age groups, and special groups such as pregnant women. Countries should define specific actions, responsible parties, and timelines in their unique contexts, while reflecting on the necessary resources.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Committee of Prolepsis Institute. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and administration of the study: SD, MM, and PK; Literature review coordination: SD, GM, MT, and FD’A; Qualitative research coordination: PK, NP, ND, and MR; Data extraction and analysis: MR, GM, SS, AB, CD, CF, AG, SC, NP, and ND; Writing—original draft preparation: SS, GM, and MR; Writing—review and editing: all authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research presented in this article was performed within the AcToVax4NAM project which was co-funded by the European Union’s Health Programme 2014-2020 - Project Number: 101018349. The funder has no responsibility concerning the content of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article has been written with the support of the other Consortium Partners Organization: Fundacio Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron - Institut de Recerca (VHIR), Spain; Center for Social Innovation Ltd (CSI), Cyprus; Ministry of Health (Mohgr), Greece; Ethno-Medizinisches Zentrum Ev (EMZ), Germany; Ministry For Health - Government of Malta (MFH), Malta; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego PZH-PIB (NIZP PZH-PIB), Poland; Fundatia Romtens (ROMTENS), Romania. We acknowledge the insightful remarks on the study from Lara Tavoschi (University of Pisa, Italy), Richard Wayne (AcToVax4NAM project external evaluator), David Ingleby (University of Amsterdam), Teymur Noori and Karam Adel Ali (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2023.1605580/full#supplementary-material

References

1.World Health Organization. Vaccines and Immunization (2019). Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/vaccines-and-immunization#tab=tab_1 (Accessed November 2, 2022).

2. Giambi, C, Del Manso, M, Dalla Zuanna, T, Riccardo, F, Bella, A, Caporali, MG, et al. National Immunization Strategies Targeting Migrants in Six European Countries. Vaccine (2019) 37(32):4610–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.060

3. Hargreaves, S, Crawshaw, AF, and Deal, A. Ensuring the Integration of Refugees and Migrants in Immunization Policies, Planning and Service Delivery Globally. Geneva: World Health Organization (2022).

4.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Delivery of Immunization Services for Refugees and Migrants: Technical Guidance. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2019).

5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Public Health Guidance on Screening and Vaccination for Infectious Diseases in Newly Arrived Migrants Within the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC (2018).

6.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Strategy and Action Plan for Refugee and Migrant Health in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2016). Published online.

7.World Health Organization. Seventy-Third World Health Assembly: Geneva, 18–19 May (De Minimis) and 9–14 November (Resumed) 2020: Resolutions and Decisions, Annexes. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020). Published online.

8.AcToVax4NAM. Increased Access to Vaccination for Newly Arrived Migrants (2021). Avaialable from: https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/portal/screen/how-to-participate/org-details/999999999/project/101018349/program/31061266/details (Accessed July 19, 2023).

9. Hsieh, H-F, and Shannon, SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res (2005) 15(9):1277–88. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

10. Abdi, I, Menzies, R, and Seale, H. Barriers and Facilitators of Immunisation in Refugees and Migrants in Australia: An East-African Case Study. Vaccine (2019) 37(44):6724–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.025

11.Sistema Sanitario Regione Liguria. Vaccinazione Anti COVID-19 Soggetti Non Registrati Nel Sistema Sanitario Regionale Della Liguria. Ordinanza N. 3/2021 – Circolare ALISA N. 15226 Del 21.4.21. Genova: Regione Liguria (2021).

12. Allen, EM, Lee, HY, Pratt, R, Vang, H, Desai, JR, Dube, A, et al. Facilitators and Barriers of Cervical Cancer Screening and Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination Among Somali Refugee Women in the United States: A Qualitative Analysis. J Transcult Nurs (2019) 30(1):55–63. doi:10.1177/1043659618796909

13. Armocida, B, Formenti, B, Missoni, E, D'Apice, C, Marchese, V, Calvi, M, et al. Challenges in the Equitable Access to COVID-19 Vaccines for Migrant Populations in Europe. Lancet Reg Heal - Eur (2021) 6:100147. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100147

14. Bandini, L, Caraglia, A, Caredda, E, Declich, S, Grazia Dente, M, Filia, A, et al. Vaccinazione Contro COVID-19 Nelle Comunità Residenziali in Italia: Priorità e Modalità Di Implementazione AD Interim. Rome: Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) (2021).

15. Bartovic, J, Datta, SS, Severoni, S, and D’Anna, V. Ensuring Equitable Access to Vaccines for Refugees and Migrants During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Bull World Health Organ (2021) 99:3–A. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.267690

16. Bradby, H, Humphris, R, Newall, D, and Phillimore, J. Public Health Aspects of Migrant Health: A Review of the Evidence on Health Status for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the European Region. WHO (2015). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326348/9789289051101-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (Accessed July 19, 2023).

17. Crawshaw, AF, Deal, A, Rustage, K, Forster, AS, Campos-Matos, I, Vandrevala, T, et al. What Must Be Done to Tackle Vaccine Hesitancy and Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccination in Migrants? J Trav Med (2021) 28(4):taab048. doi:10.1093/jtm/taab048

18. Dalla Zuanna, T, Del Manso, M, Giambi, C, Riccardo, F, Bella, A, Caporali, MG, et al. Immunization Offer Targeting Migrants: Policies and Practices in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(5):968. doi:10.3390/ijerph15050968

19. De Vito, E, Parente, P, de Waure, C, Poscia, A, and Ricciardi, W. A Review of Evidence on Equitable Delivery, Access and Utilization of Immunization Services for Migrants and Refugees in the WHO European Region. London: World Health Organization (2017).

20. Deal, A, Hayward, SE, Huda, M, Knights, F, Crawshaw, AF, Carter, J, et al. Strategies and Action Points to Ensure Equitable Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccinations: A National Qualitative Interview Study to Explore the Views of Undocumented Migrants, Asylum Seekers, and Refugees. J Migr Heal (2021) 4:100050. doi:10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100050

21. Declich, S, Dente, MG, Greenaway, C, and Castelli, F. Infectious Diseases Among Migrant Populations. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. Oxford University Press (2021). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.67

22. Del Manso, M, Giambi, C, Dalla Zuanna, T, Riccardo, F, Bella, A, Caporali, MG, et al. Report on the Survey on Immunization Offer Targeting Newly Arrived Migrants. CARE Project (2017).

23. Driedger, M, Mayhew, A, Welch, V, Agbata, E, Gruner, D, Greenaway, C, et al. Accessibility and Acceptability of Infectious Disease Interventions Among Migrants in the EU/EEA: A CERQual Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(11):2329. doi:10.3390/ijerph15112329

24.Epicentro. G-START: Poster di Comunicazione Multilingua ai Tempi del COVID-19. Rome: Epicentro (2021). Published online.

25.Epicentro. G-START: Materiali di Comunicazione Multilingua Adattati per il Contesto Regionale. Rome: Epicentro (2021). Published online.

26.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Expert Opinion on the Public Health Needs of Irregular Migrants, Refugees or Asylum Seekers Across the EU’s Southern and South-Eastern Borders. ECDC (2015). Published online.

27.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Reducing COVID-19 Transmission and Strengthening Vaccine Uptake Among Migrant Populations in the EU/EEA. ECDC (2021).

28.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Overview of the Implementation of COVID-19 Vaccination Strategies and Deployment Plans in the EU/EEA. Technical Report (2021).

29. Fabiani, M, Di Napoli, A, Riccardo, F, Gargiulo, L, Declich, S, and Petrelli, A. Differenze Nella Copertura Vaccinale Antinfluenzale Tra Sottogruppi Di Immigrati Adulti Residenti in Italia a Rischio Di Complicanze (2012-2013). Epidemiol Prev (2017) 41:50–6. doi:10.19191/EP17.3-4S1.P050.065

30. Galán Rafael, G. Manual de Atención Sanitaria a Inmigrantes: Guía Para Profesionales de la Salud. Sevilla: Consejería de Salud (2007). Published online.

31. Geraci, S, and Verona, A. Gli Invisibili e il Diritto al Vaccino. SaluteInternazionale.Info. Rome: SaluteInternazionale.info (2021). Published online.

32. Ghebrendrias, S, Pfeil, S, Crouthamel, B, Chalmiers, M, Kully, G, and Mody, S. An Examination of Misconceptions and Their Impact on Cervical Cancer Prevention Practices Among Sub-Saharan African and Middle Eastern Refugees. Heal Equity (2021) 5(1):382–9. doi:10.1089/heq.2020.0125

33. Giambi, C, Del Manso, M, Dente, M, Napoli, C, Montaño-Remacha, C, Riccardo, F, et al. Immunization Strategies Targeting Newly Arrived Migrants in Non-EU Countries of the Mediterranean Basin and Black Sea. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2017) 14(5):459. doi:10.3390/ijerph14050459

34. Godoy-Ramirez, K, Byström, E, Lindstrand, A, Butler, R, Ascher, H, and Kulane, A. Exploring Childhood Immunization Among Undocumented Migrants in Sweden - Following Qualitative Study and the World Health Organizations Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Public Health (2019) 171:97–105. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.04.008

35. Hargreaves, S, Nellums, LB, Ravensbergen, SJ, Friedland, JS, and Stienstra, Y, ESGITM Working Group on Vaccination in Migrants. Divergent Approaches in the Vaccination of Recently Arrived Migrants to Europe: A Survey of National Experts From 32 Countries, 2017. Eurosurveillance (2018) 23(41):1700772. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.41.1700772

36. Ismael, HG. Protocolo de Vacunación de Personas Refugiadas Adultas Y Menores En Cantabria. In Dirección General de Salud Pública, Consejería de Sanidad Asturias (Asturias). (2016).

37. Hui, C, Dunn, J, Morton, R, Staub, LP, Tran, A, Hargreaves, S, et al. Interventions to Improve Vaccination Uptake and Cost Effectiveness of Vaccination Strategies in Newly Arrived Migrants in the EU/EEA: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(10):2065. doi:10.3390/ijerph15102065

38.International Organization for Migration - IOM UM. Migration Flow (2019). Available from: Https://Migration.Iom.Int/Datasets/Europe-%E2%80%94-Mixed-Migration-Flows-Europe-Quarterlyoverview-January-December-2019 Https://Migration.Iom.Int/Europe?Type=arrivals (Accessed July 19, 2023).

39.Italian Ministry of Health. Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale PNPV 2017-2019. Rome: Italian Ministry of Health (2017).

40. Karnaki, P, and Katsas, K. Pilot Reports and Final Recommendations. Mig-healthCare (2018). Published online.

41. Karnaki, P, Nikolakopoulos, S, Tsiampalis, T, Petralias, A, Bradby, H, Hamed, S, et al. Survey and Interview Findings. Physical and Mental Health Profile of Vulnerable Migrants/Refugees in the EU Including Needs, Expectations and Capacities of Service Providers. Mig-healthCare (2018). Published online.

42. Knights, F, Carter, J, Deal, A, Crawshaw, AF, Hayward, SE, Jones, L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Migrants’ Access to Primary Care and Implications for Vaccine Roll-Out: A National Qualitative Study. Br J Gen Pract (2021) 71(709):e583–e595. doi:10.3399/BJGP.2021.0028

43. Krishnaswamy, S, Cheng, AC, Wallace, EM, Buttery, J, and Giles, ML. Understanding the Barriers to Uptake of Antenatal Vaccination by Women From Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds: A Cross-Sectional Study. Hum Vaccin Immunother (2018) 14(7):1591–8. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1445455

44. Mahimbo, A, Seale, H, Smith, M, and Heywood, A. Challenges in Immunisation Service Delivery for Refugees in Australia: A Health System Perspective. Vaccine (2017) 35(38):5148–55. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.002

45. McComb, E, Ramsden, V, Olatunbosun, O, and Williams-Roberts, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Uptake Among an Immigrant and Refugee Catch-Up Group in a Western Canadian Province. J Immigr Minor Heal (2018) 20(6):1424–8. doi:10.1007/s10903-018-0709-6

46. Mellou, K, Silvestros, C, Saranti-Papasaranti, E, Koustenis, A, Pavlopoulou, ID, Georgakopoulou, T, et al. Increasing Childhood Vaccination Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Population in Greece Through the European Programme PHILOS, April 2017 to April 2018. Eurosurveillance (2019) 24(27):1800326. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.27.1800326

47. Mipatrini, D, Stefanelli, P, Severoni, S, and Rezza, G. Vaccinations in Migrants and Refugees: A challenge for European Health Systems. A Systematic Review of Current Scientific Evidence. Pathog Glob Health (2017) 111(2):59–68. doi:10.1080/20477724.2017.1281374

48. Noori, T, Hargreaves, S, Greenaway, C, van der Werf, M, Driedger, M, Morton, RL, et al. Strengthening Screening for Infectious Diseases and Vaccination Among Migrants in Europe: What Is Needed to Close the Implementation Gaps? Trav Med Infect Dis (2021) 39:101715. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101715

49. Ortiz, E, Scanlon, B, Mullens, A, and Durham, J. Effectiveness of Interventions for Hepatitis B and C: A Systematic Review of Vaccination, Screening, Health Promotion and Linkage to Care Within Higher Income Countries. J Community Health (2020) 45(1):201–18. doi:10.1007/s10900-019-00699-6

50. Pavli, A, and Maltezou, H. Health Problems of Newly Arrived Migrants and Refugees in Europe. J Trav Med (2017) 24(4):tax016. doi:10.1093/jtm/tax016

51. Perry, M, Townson, M, Cottrell, S, Fagan, L, Edwards, J, Saunders, J, et al. Inequalities in Vaccination Coverage and Differences in Follow-Up Procedures for Asylum-Seeking Children Arriving in Wales, UK. Eur J Pediatr (2020) 179(1):171–5. doi:10.1007/s00431-019-03485-7

52.PICUM (Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants). The COVID-19 Vaccines & Undocumented Migrants in Greece (2021). Available from: https://picum.org/COVID-19-vaccines-undocumented-migrants-greece/ (Accessed July 19, 2023).

53. Prymula, R, Shaw, J, Chlibek, R, Urbancikova, I, and Prymulova, K. Vaccination in Newly Arrived Immigrants to the European Union. Vaccine (2018) 36(36):5385–90. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.079

54. Razum, O, and Brzoska, P. Einwanderung. In: Gesundheit Als Gesamtgesellschaftliche Aufgabe. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden (2020). p. 99–108. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-30504-8_8

55. Rechel, B, Priaulx, J, Richardson, E, and McKee, M. The Organization and Delivery of Vaccination Services in the European Union. Eur J Public Health (2019) 29(4):ckz185.375. Published online. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.375

56.Regione Toscana. La Vaccinazione dei Minori e Adulti Immigrati (2019). Website page updated 04.12.2019 Available from: https://www.regione.toscana.it/-/la-vaccinazione-dei-minori-e-adulti-immigrati (Accessed December 04, 2019).

57. Riza, E, and Kalkman, S. Report on Models of Community Health and Social Care and Best Practices. Mighealthcare (2018).

58.Robert Koch-Institut. Epidemiologisches Bulletin. Recommendations of the Permanent Vaccination Commission at the Robert Koch Institute 2020/2021. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut (2020).

59. Rubens-Augustson, T, Wilson, LA, Murphy, MS, Jardine, C, Pottie, K, Hui, C, et al. Healthcare Provider Perspectives on the Uptake of the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Among Newcomers to Canada: A Qualitative Study. Hum Vaccin Immunother (2019) 15(7-8):1697–707. doi:10.1080/21645515.2018.1539604

60. Shetty, AK. Infectious Diseases Among Refugee Children. Children (2019) 6(12):129. doi:10.3390/children6120129

61. Socha, A, and Klein, J. What Are the Challenges in the Vaccination of Migrants in Norway From Healthcare Provider Perspectives? A Qualitative, Phenomenological Study. BMJ Open (2020) 10(11):e040974. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040974

62. Spallek, J, Schumann, M, and Reeske-Behrens, A. Migration und Gesundheit – Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten von Gesundheitsversorgung und Public Health in Diversen Gesellschaften. In: Gesundheitswissenschaften. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (2019). p. 527–38. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-58314-2_49

63. Sypsa, V. Hprolispsis: HBV & HCV Infections Among Roma & Migrants in Greece. Slovenia: VHPV (2016).

64.Tavolo Immigrazione e Salute (TIS) e Tavolo Asilo e Immigrati (TAI). Letter (Italy). Oggetto: Richiesta Urgente Di Indicazioni Nazionali Per Porre Fine Alle Disparità Di Accesso Alla Campagna Vaccinale Anti-SARS-CoV-2/covid-19. Rome: Tavolo Immigrazione e Salute e Tavolo Asilo e Immigrati (2021).

65.Tavolo Asilo e Immigrazione. Indagine Sulla Disponibilità a Vaccinarsi Contro Il COVID-19 Da Parte Delle Persone Ospitate Nei Centri/Strutture Di Accoglienza in Italia. Dossier COVID-19. N3; 2021. Rome: Tavolo Asilo e Immigrati (2021).

66. Teerawattananon, Y, Teo, YY, Lim, JFY, Hsu, LY, and Dabak, S. Vaccinating Undocumented Migrants Against Covid-19. BMJ (2021) 373:n1608. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1608

67. Theodorou, M, Charalambous, C, Petrou, C, and Cylus, J. Cyprus: Health System Review. Health Syst Transit (2012) 14(6):1–128.

68. Thomas, CM, Osterholm, MT, and Stauffer, WM. Critical Considerations for COVID-19 Vaccination of Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants. Am J Trop Med Hyg (2021) 104(2):433–5. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1614

69. Tosti, ME, Marceca, M, Eugeni, E, D'Angelo, F, Geraci, S, Declich, S, et al. Health Assessment for Migrants and Asylum Seekers Upon Arrival and While Hosted in Reception Centres: Italian Guidelines. Health Policy (New York) (2021) 125(3):393–405. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.12.010

70. Vita, S, Sinopoli, MT, Fontanelli Sulekova, L, Morucci, L, Lopalco, M, Spaziante, M, et al. Vaccination Campaign Strategies in Recently Arrived Migrants: Experience of an Italian Reception Centre. J Infect Dev Ctries (2019) 13(12):1159–64. doi:10.3855/jidc.11815

71.WHO-UNICEF. Guidance on Developing a National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 Vaccines: Interim Guidance. Geneva: WHO (2021).

72.WHO-UNHCR-UNICEF. WHO-UNHCR-UNICEF. Joint Statement on General Principles on Vaccination of Refugees, Asylum-Seekers and Migrants in the WHO European Region. World Health Organization (2015).

73. Williams, GA, Bacci, S, Shadwick, R, Tillmann, T, Rechel, B, Noori, T, et al. Measles Among Migrants in the European Union and the European Economic Area. Scand J Public Health (2016) 44(1):6–13. doi:10.1177/1403494815610182

74. Wilson, L, Rubens-Augustson, T, Murphy, M, Jardine, C, Crowcroft, N, Hui, C, et al. Barriers to Immunization Among Newcomers: A Systematic Review. Vaccine (2018) 36(8):1055–62. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.025

75.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. European Vaccine Action Plan 2015-2020. Copenhagen: WHO (2014). Published online.

76.World Health Organization. Vaccination in Humanitarian Emergencies: Implementation Guide. Geneva: WHO (2017). Published online.

77.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Eighteenth Meeting of the European Technical Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (ETAGE): 12–13 November 2018, Copenhagen, Denmark. Copenhagen: WHO (2018).

78.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Health of Refugee and Migrant Children. Technical Guidance. Copenhagen: WHO (2018). Published online.

79.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region: No Public Health Without Refugee and Migrant Health. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2018). Published online.

80.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Health Diplomacy: Spotlight on Refugees and Migrants. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2019). Published online.

81.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2019). Published online.

82.World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Collection and Integration of Data on Refugee and Migrant Health in the WHO European Region. Technical guidance. Copenhagen: World Health Organization (2020).

Keywords: vaccination coverage, newly arrived migrants, general conceptual framework, system barriers, strategies

Citation: Scarso S, Marchetti G, Russo ML, D’Angelo F, Tosti ME, Bellini A, De Marchi C, Ferrari C, Gatta A, Caminada S, Papaevgeniou N, Dalma N, Karnaki P, Marceca M and Declich S (2023) Access to Vaccination for Newly Arrived Migrants: Developing a General Conceptual Framework for Understanding How to Improve Vaccination Coverage in European Countries. Int J Public Health 68:1605580. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605580

Received: 11 November 2022; Accepted: 20 July 2023;

Published: 07 August 2023.

Edited by:

Sonja Merten, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Erma Manoncourt, Sciences Po, FranceCopyright © 2023 Scarso, Marchetti, Russo, D’Angelo, Tosti, Bellini, De Marchi, Ferrari, Gatta, Caminada, Papaevgeniou, Dalma, Karnaki, Marceca and Declich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Salvatore Scarso, c2FsdmF0b3JlLnNjYXJzb0Bpc3MuaXQ=

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Migration Health Around the Globe—A Construction Site With Many Challenges”

Salvatore Scarso

Salvatore Scarso Giulia Marchetti1,3

Giulia Marchetti1,3 Maria Laura Russo

Maria Laura Russo Caterina Ferrari

Caterina Ferrari Nikoletta Papaevgeniou

Nikoletta Papaevgeniou