- 1Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, India

- 2Director of Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, India

- 3Head of School (Health and Social Care), Anglia Ruskin University, London, United Kingdom

- 4Professor of Surgery and Global Health, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, United States

- 5Adjunct Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, India

Objectives: We carried out a mixed method study to understand why patients did not avail of surgical care in an urban slum in India.

Methods: In our earlier study, we found that out of 10,330 people, 3.46% needed surgery; 42% did not avail of surgery (unmet needs). We conducted a follow-up study to understand reasons for not availing surgery, 141 in met needs, 91 in unmet needs. We administered 2 instruments, 16 in-depth interviews and 1 focused group discussion.

Results: Responses from the 2 groups for “the Socio-culturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale for a Developing Country Setting” scale did not have significant difference except for, prescription of medicines, patients with unmet needs were less likely to agree (p = 0.076). Results between 2 groups regarding “Patient perceptions of quality” did not show significant difference except for doctors answering questions where a higher proportion of unmet need group agreed (p = 0.064). Similar observations were made in the in depth interviews and focus group.

Conclusion: There is a need for understanding trust issues with health service delivery related to surgical care for marginalized populations.

Introduction

Surgery has become an integral part of public health with an estimated 234 million operations performed yearly. Surgical intervention is required to promote, prevent and restore health, in every age group [1]. The issue of surgical unmet needs to be addressed at the macro and micro levels. At the macro level, governance and national policy are important [2, 3] while fear of anaesthesia, lack of local social support, difficulty navigating the healthcare system, expensive travel, and lack of privacy have been implicated for low uptake of free essential surgical procedures [4]. Other potential factors at the micro-level are poor health literacy, trust deficit, lack of informed consent which come into play during their decision not to proceed for surgery [5].

The current study is an in-depth exploration of our initial study [6] in which we studied 10,330 populations from the urban slums of Ahmedabad city in the state of Gujarat, India in 2019–20 [6]. Out of 3.46% of surgical need, 42% did not avail surgical care needed for a variety of reasons. Financial reasons (34.5%) and lack of trust (35.3%) were major reasons for not availing essential surgical care despite obtaining consultation from qualified surgeons under India’s universal health coverage (UHC) (https://www.india.gov.in/spotlight/ayushman-bharat-national-health-protection-mission).

We carried out an instrument-based quantitative survey supplemented by a qualitative study to understand the reasons for patients not availing of surgical procedures despite widespread awareness of UHC in India [7]. We focused on the doctor-patient relationship and broader social considerations, which may impact their decision-making. Focus on the doctor-patient relationship has primarily manifested in the form of trust [8] control [9], perceptions of quality [10]. The findings of the study could be used to strengthen surgical systems in India and other LMICs.

Methods

We contacted 274 people with surgical needs from our original study [6] to participate in exploration of their experience using standardized instruments validated in the Indian population—232 participants agreed out of which, 141 were from met needs, and 91 from the unmet needs group.

Study Instruments: We administered 2 instruments “the Socio-culturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale for a Developing Country Setting” [11, 12] and “Patient perceptions of quality” [13]. The Socio-culturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale for a Developing Country Setting [9] is an excellent tool to study the micro aspects of surgeon-patient interaction and issues which impact upon the low uptake of surgical intervention. The second instrument “Patient perceptions of quality” was administered to understand patients’ viewpoints if there were specific reasons why ∼50% of patients refused surgical procedures despite availing consultation under UHC.

Qualitative study: A subgroup of participants was individually interviewed (n = 16) and one focus group discussion (n = 5) was done. The subgroup was a mix of met (n = 7) and unmet needs (n = 14). Supplementary Appendix S2 gives the set of questions asked for the qualitative part of the study.

Data collection: The tools were translated into Gujarati by certified translators (Supplementary Appendix S1) and data was collected on tablets. A web-based application (ODK) was developed for data collection.

Study Analysis: Quantitative analysis was done using statistical software SPSS version 23. Descriptive analysis was used to assess prevalence of surgical conditions and the unmet needs. As the data was homogenous, regression analysis could not be done. Also the difference between both the groups was not major, so we could not do multivariate analysis. P values were obtained to see differences between met need and unmet need patients. Qualitative data was analysed using ‘Framework Method’ as described by Gale et al. [14]. We used the same domains as in the quantitative tools. We used this particular methodology as it is flexible and can generate themes which could be analysed by multi-disciplinary research teams that comprise of healthcare professionals, psychologists, sociologists, economists, and service users, as in our study.

Results

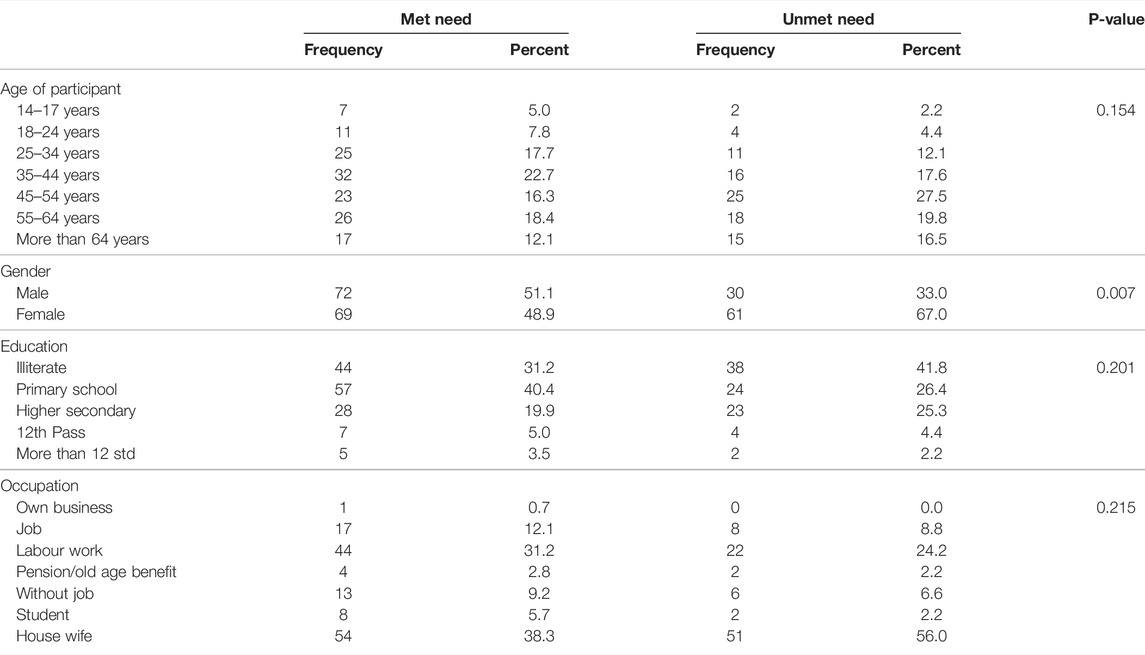

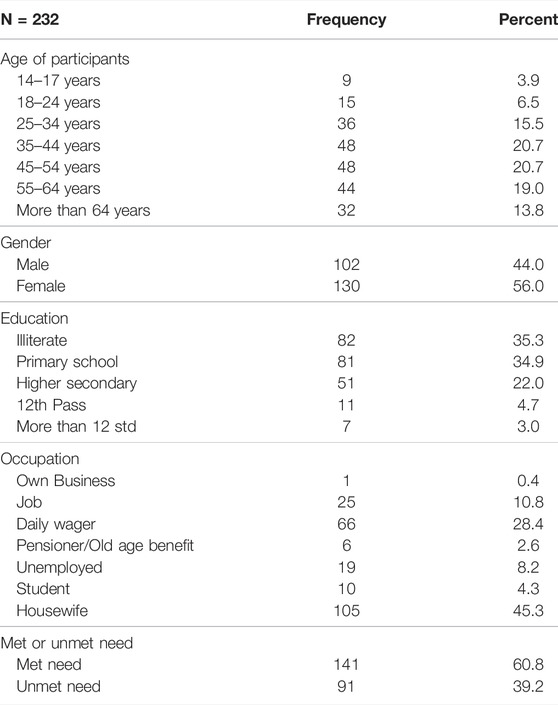

Demographic information are given in Table 1. 70% had less than 10 years of education. 45% were housewives while 28% were daily wagers. As shown in Table 2, the met needs group was younger with higher proportion of males. The unmet needs group had a higher proportion of illiterate persons and housewives. Except for gender (p = 0.007), there was no statistically significant difference between both groups.

TABLE 1. Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics and demographics (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

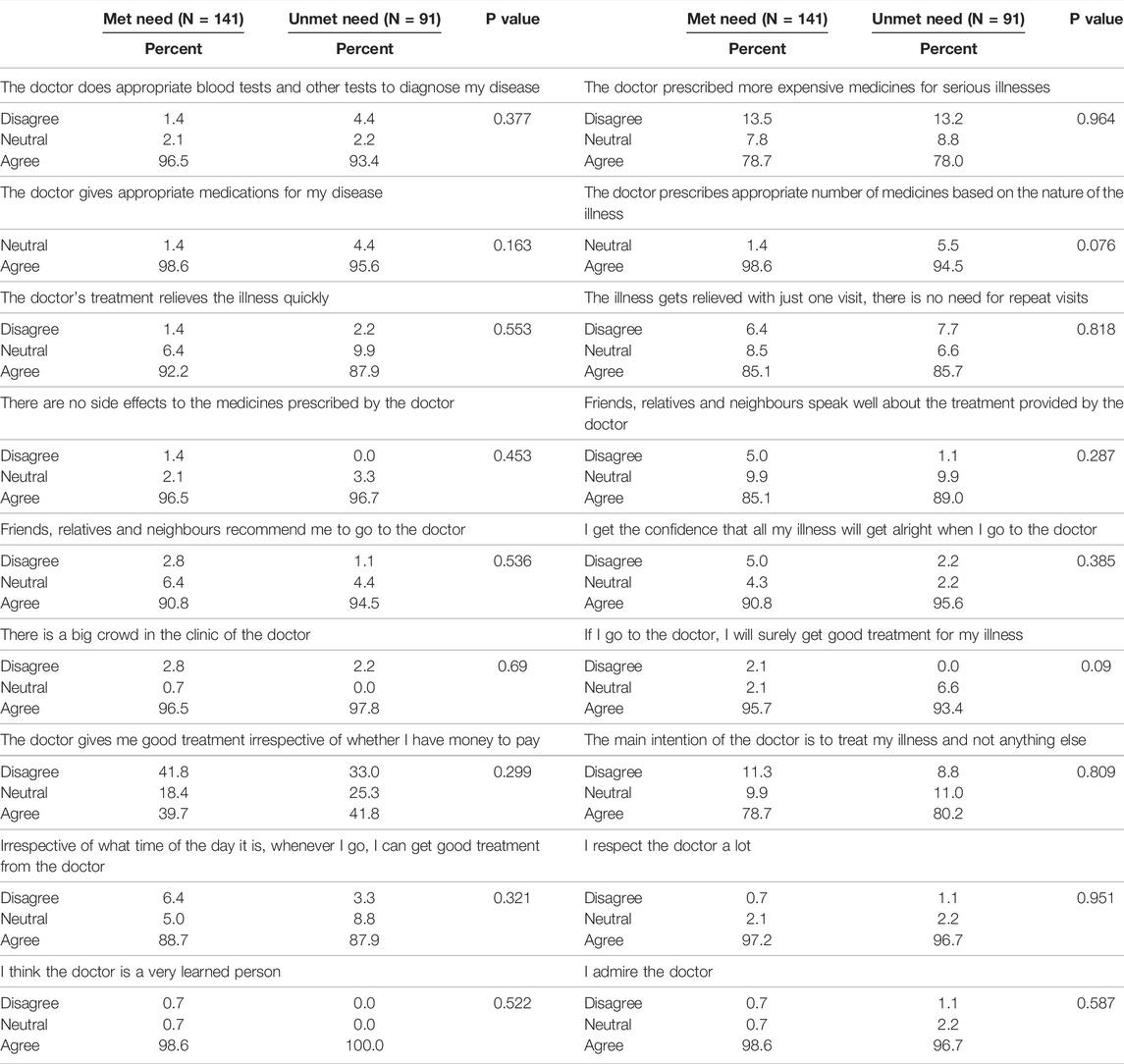

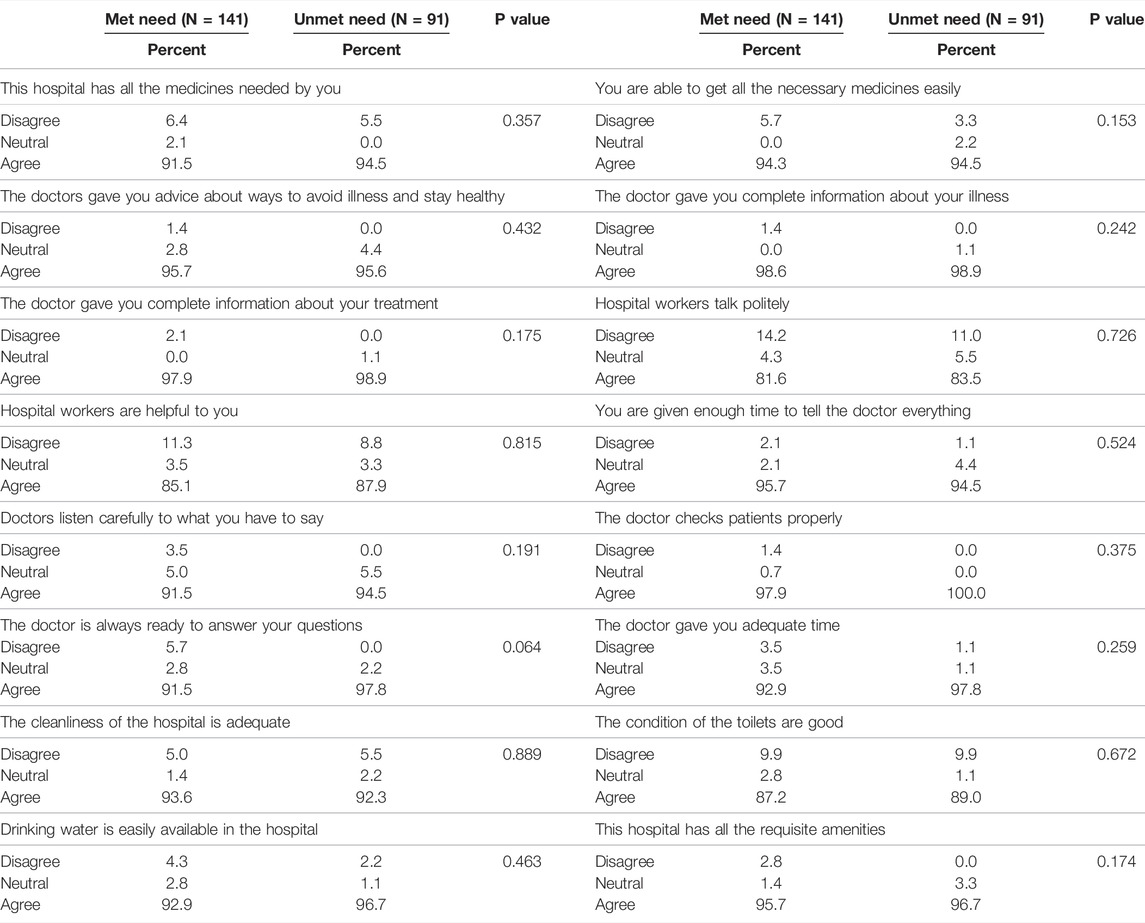

Table 3 compares the two groups for the “the Socio-culturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale for a Developing Country Setting” scale. Both groups were similar and did not have statistically significant differences except for, prescription of medicines, where unmet needs was less likely to agree (p = 0.076).

TABLE 3. Comparison between met needs and unmet needs for the “socio-culturally competent trust in physician scale for a developing country Setting” (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

Table 4 shows the comparison between two groups for “Patient perceptions of quality” instrument. There was no statistically significant difference between met and unmet needs groups except for doctors answering questions where a higher proportion of patients in unmet need agreed (p = 0.064).

TABLE 4. Comparison between met needs and unmet needs for ‘patient perception of quality’. (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

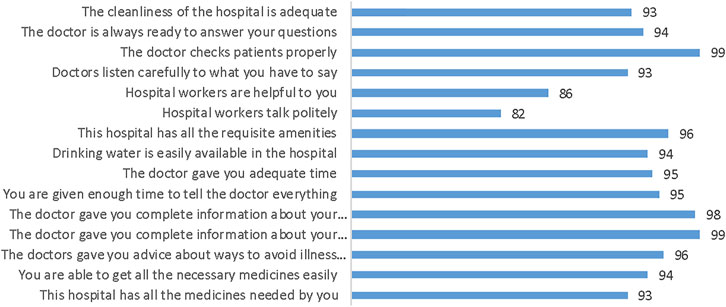

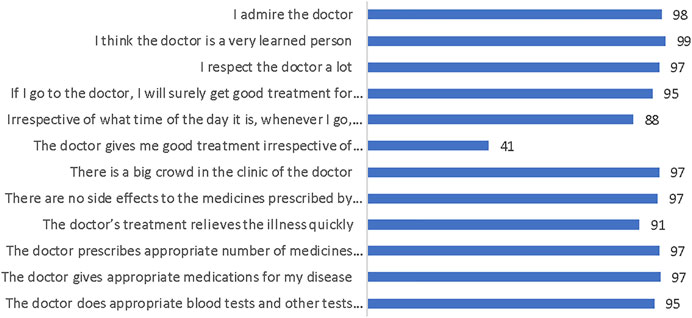

Figure 1 shows that the majority of participants (>90%) trusted doctors concerning investigations and prescription of medicines, and felt quick relief with the prescribed treatment. 97% indicated that the clinic was crowded, while only 41% agreed that the doctor treated them well irrespective of their paying capacity. More than 80% agreed that timings were flexible and the doctor can treat all illnesses while greater than 95% had faith in the skills of the doctor.

FIGURE 1. “Socio-culturally competent trust in physician scale for a developing country setting.” (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

Figure 2 shows that greater than 90% of the participants were satisfied with the information/time provided by the doctor and the availability of the medicines/basic amenities. 82% of the participants indicated that hospital workers were polite and 86% indicated they were helpful.

Qualitative data from the in-depth interviews and focus group discussion validated the results from quantitative data. In both methods, participants agreed that there was high level of trust for the providers but felt that at times they were not given the depth of attention they expected. There was also a perception that multiple visits were required for relief of their symptoms which had financial implications. A male participant shared his experience and said, “During first visit, they told me my haemoglobin is low so I took 1-month course and went to the hospital. They told that you need to again take 1-month medicine course for haemoglobin. My haemoglobin increased to 12.5% so I asked for appointment for operation. They replied that they will give date after 15 days but they didn’t give me date and my problem increased.” A female participant said, “One doctor told with the help of medicine, you will recover. But it did not work so I went to another hospital and they operated immediately which caused great deal of stress and disruption of routine in the family.”

Discussion

Our study showed the overall level of trust and perception of quality was high and patients held the doctors and hospital facilities in high regard. Met and unmet needs groups were similar in regards to trust and perception of quality. Less proportion of participants agreed that doctors treated them well irrespective of paying capacity. This indicates that finances affect trust and quality of care. Similar observations were made in the qualitative study using same domains as in quantitative data.

Trust in physicians is the unwritten covenant between patient and their physicians of mutual respect. A study in South India found that patients valued competence of the physician; behavior and assurance of treatment [15]. A study showed that trust in physicians was influenced by behavior on the physician and spending more time with the patient [16]. Giving patients time to explain the reason for visit, taking time to answer, enquiring about the family dynamics, involving them in decision-making and providing with medical information were determinants of trust in the physician and satisfaction [17].

Studies on user perceptions in LMIC have shown that patients were able to evaluate structural, process, and outcome measures of quality [18–21]. There is an evidence that doctors with better communication and interpersonal skills can detect problems, prevent medical crises and expensive interventions, while providing better support to their patients. This leads to better outcomes and satisfaction, lower costs, greater understanding of health issues, and adherence to the treatment process [22, 23]. We used 2 validated instruments, the Socio-culturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale and The Patient Perceptions of Quality in which majority of the participants (>90%) trusted doctors with respect to investigations, prescription of medicines and felt quick relief with the treatment. 97% indicated that the clinic was crowded, however, only 40% agreed that the doctor treated them well irrespective of their paying capacity.

Our previous work showed that financial constraints were the predominant reason for patients not availing of surgical care under UHC. Surveys carried out by the Government of India showed that the knowledge of UHC is patchy [24] and efforts have been made to increase education of patient rights and by automation [25]. However, we believe that there is widespread knowledge of UHC in Ahmedabad by the fact that almost 100% of patients obtained free surgical consultation and associated investigations. We assume that the financial constraints are a potential loss of wages during hospitalization. The majority of patients in our study were daily wagers and unlikely to have alternative means of support if they take time off for hospitalization.

It has been well documented that women in India face extensive gender discrimination in access to healthcare. Researchers calculated the number of “missing” patients by looking at the difference between the actual number of women who visited the hospital and those that should have come, based on the 2011 census. Almost two-thirds of these visits were made by male patients vs. 37% visits by female patients [26]. Another study found that average health care expenditures were lower among women than men [27]. Gender disparity was even visible in new-borns in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. Perception of illness was significantly lower in households with female versus male new-borns [28]. An observational study examined gender disparities in seeking healthcare and in-home management of diarrhea, acute respiratory infections, and fever among 530 children in a rural community of West Bengal, India, found that girls were less likely to get oral rehydration solutions during diarrhea [29].

Government schemes seeks to bridge the gender gap in the use of healthcare services by addressing a key constraint in using health services, i.e., the cost of healthcare. The underrepresentation, low coverage rates, and substantially lower benefits make women disadvantaged which are compounded with the financial burden of healthcare.

In summary, using mixed methodology, we showed that trust deficit could be mitigated by improved doctor-patient communication, in particular, by the emphasis that all patients would be treated equally irrespective of their paying capacity. The persistence of gender disparities calls for interventions at a societal level. Gender discrimination in access to healthcare could be removed by deploying female community health care workers. We have initiated a program of training surgical community workers that would sensitize gender issues. Financial toxicity needs to be removed at the governmental level by providing assistance to cover lost wages during hospitalization.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, India. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Author Disclaimer

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the author/speaker and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the Department of Defence, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or any other agency of the US Government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The concept was developed during RMJ’s Fulbright-Nehru scholarship to India (2016 and 2022).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604924/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Appendix S1 | Instruments used for quantitative study. (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

Supplementary Appendix S2 | Questions asked in the qualitative study. (Ahmedabad, India. 2022).

Abbreviations

FGD, focused group discussion; LMIC, low and middle-income countries; UHC, universal health coverage.

References

1. Bhasin, SK, Roy, R, Agrawal, S, and Sharma, R. An Epidemiological Study of Major Surgical Procedures in an Urban Population of East Delhi. Indian J Surg (2011) 73(2):131–5. doi:10.1007/s12262-010-0198-x

2. Bhandarkar, P, Gadgil, A, Patil, P, Mohan, M, and Roy, N. Estimation of the National Surgical Needs in India by Enumerating the Surgical Procedures in an Urban Community under Universal Health Coverage. World J Surg (2021) 45(1):33–40. doi:10.1007/s00268-020-05794-7

3. Shrime, MG, Bickler, SW, Alkire, BC, and Mock, C. Global burden of Surgical Disease: an Estimation from the Provider Perspective. Lancet Glob Health (2015) 3:S8–S9. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70384-5

4. Goold, SD, and Lipkin, M. The Doctor-Patient Relationship. J Gen Intern Med (1999) 14(Suppl. 1):S26–S33. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00267.x

5. Lloyd, AJ. The Extent of Patients' Understanding of the Risk of Treatments. Qual Saf Health Care (2001) 10(Suppl. 1):i14–i18. doi:10.1136/qhc.0100014

6. Vora, K, Saiyed, S, Shah, AR, Mavalankar, D, and Jindal, RM. Surgical Unmet Need in a Low-Income Area of a Metropolitan City in India: A Cross-Sectional Study. World J Surg (2020) 44(8):2511–7. doi:10.1007/s00268-020-05502-5

7. Singh, Z. Universal Health Coverage for India by 2022: a utopia or Reality? Indian J Community Med (2013) 38(2):70–3. doi:10.4103/0970-0218.112430

8. Ridd, M, Shaw, A, Lewis, G, and Salisbury, C. The Patient-Doctor Relationship: a Synthesis of the Qualitative Literature on Patients' Perspectives. Br J Gen Pract (2009) 59(561):e116–e133. doi:10.3399/bjgp09X420248

9. Kaba, R, and Sooriakumaran, P. The Evolution of the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Int J Surg (2007) 5(1):57–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.01.005

10. Rhee, KJ, and Bird, J. Perceptions and Satisfaction with Emergency Department Care. J Emerg Med (1996) 14(6):679–83. doi:10.1016/s0736-4679(96)00176-x

11. Gopichandran, V, Wouters, E, and Chetlapalli, SK. Development and Validation of a Socioculturally Competent Trust in Physician Scale for a Developing Country Setting. BMJ Open (2015) 5(4):e007305. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007305

12. Gopichandran, V, and Chetlapalli, SK. Trust in the Physician-Patient Relationship in Developing Healthcare Settings: a Quantitative Exploration. Ijme (2015) 12(3):141–8. doi:10.20529/IJME.2015.043

13. Rao, KD, Peters, DH, and Bandeen-Roche, K. Towards Patient-Centered Health Services in India-a Scale to Measure Patient Perceptions of Quality. Int J Qual Health Care (2006) 18:414–21. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzl049

14. Gale, NK, Heath, G, Cameron, E, Rashid, S, and Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med Res Methodol (2013) 13:117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

15. Gopichandran, V, and Chetlapalli, SK. Dimensions and Determinants of Trust in Health Care in Resource Poor Settings - A Qualitative Exploration. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e69170. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069170

16. Fiscella, K, Meldrum, S, Franks, P, Shields, CG, Duberstein, P, McDaniel, SH, et al. Patient Trust. Med Care (2004) 42:1049–55. doi:10.1097/00005650-200411000-00003

17. Keating, NL, Green, DC, Kao, AC, Gazmararian, JA, Wu, VY, and Cleary, PD. How Are Patients' Specific Ambulatory Care Experiences Related to Trust, Satisfaction, and Considering Changing Physicians? J Gen Intern Med (2002) 17:29–39. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10209.x

18. Haddad, S, Fournier, P, Machouf, N, and Yatara, F. What Does Quality Mean to Lay People? Community Perceptions of Primary Health Care Services in Guinea. Soc Sci Med (1998) 47:381–94. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00075-6

19. Baltussen, R, Ye, Y, Haddad, S, and Sauerborn, RS. Perceived Quality of Care of Primary Health Care Services in Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan (2002) 17:42–8. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.1.42

20. Andaleeb, SS. Service Quality Perceptions and Patient Satisfaction: a Study of Hospitals in a Developing Country. Soc Sci Med (2001) 52:1359–70. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00235-5

21.Population Council. Improving Quality of Care in India’s Family Welfare Programme – the Challenge Ahead. New York: Population Council (1999).

22. Ha, JF, and Longnecker, N. Doctor-patient Communication: a Review. Ochsner J (2010) 10(1):38–43.

23. Chipidza, FE, Wallwork, RS, and Stern, TA. Impact of the Doctor-Patient Relationship. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord (2015) 17(5). doi:10.4088/PCC.15f0184010.4088/PCC.15f01840

24.National Health Authority. Accessing Ayushman Bharat- Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY): A Case Study of Three States (Bihar, Haryana and Tamil Nadu) (2021). https://pmjay.gov.in/sites/default/files/2021-05/Working%20paper%20006-%20A%20case%20study%20of%20three%20states%20under%20AB%20PM-JAY.pdf (Accessed 0111, 2022).

25.National Health Authority. Lessons Learned in One Year Implementation of PM-JAY (2019). https://www.pmjay.gov.in/sites/default/files/2019-09/Lessons%20Learnt%20small%20version.pdf (Accessed 0111, 2022).

26. Kapoor, M, Agrawal, D, Ravi, S, Roy, A, Subramanian, SV, and Guleria, R. Missing Female Patients: an Observational Analysis of Sex Ratio Among Outpatients in a Referral Tertiary Care Public Hospital in India. BMJ Open (2019) 9:e026850. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026850

27. Moradhvaj, SN, and Saikia, N. Gender Disparities in Health Care Expenditures and Financing Strategies (HCFS) for Inpatient Care in India. SSM - Popul Health (2019) 9:100372. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100372

28. Willis, JR, Kumar, V, Mohanty, S, Singh, P, Singh, V, Baqui, AH, et al. Gender Differences in Perception and Care-Seeking for Illness of Newborns in Rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J Health Popul Nutr (2009) 27(1):62–71. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v27i1.3318

Keywords: universal health coverage, unmet surgical need, low and middle-income countries, gender discrimination, trust and perception of quality, India

Citation: Vora K, Saiyed S, Mavalankar D, Baines LS and Jindal RM (2022) Trust Deficit in Surgical Systems in an Urban Slum in India Under Universal Health Coverage: A Mixed Method Study. Int J Public Health 67:1604924. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604924

Received: 17 March 2022; Accepted: 22 June 2022;

Published: 14 July 2022.

Edited by:

Nino Kuenzli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), SwitzerlandCopyright © 2022 Vora, Saiyed, Mavalankar, Baines and Jindal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rahul M. Jindal, amluZGFsckBtc24uY29t

Kranti Vora1

Kranti Vora1 Rahul M. Jindal

Rahul M. Jindal