- 1Department of Public Health, School of Health and Life Sciences, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 2Begum Rabeya Khatun Chowdhury Nursing College, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh

- 3Health Services Administration, College of Health Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 4NSU Global Health Institute (NGHI), North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Objectives: To investigate burnout among Bangladeshi nurses and the factors that influence it, particularly the association of workplace bullying (WPB) and workplace violence (WPV) with burnout.

Methods: This cross-sectional study collected data from 1,264 Bangladeshi nurses. Mixed-effects Poisson regression models were fitted to find the adjusted association between WPB, WPV, and burnout.

Results: Burnout was found to be prevalent in 54.19% of 1,264 nurses. 61.79% of nurses reported that they had been bullied, and 16.3% of nurses reported experience of “intermediate and high” levels of workplace violence in the previous year. Nurses who were exposed to “high risk bullying” (RR = 2.29, CI: 1.53–3.41) and “targeted bullying” (RR = 4.86, CI: 3.32–7.11) had a higher risk of burnout than those who were not. Similarly, WPV exposed groups at “intermediate and high” levels had a higher risk of burnout (RR = 3.65, CI: 2.40–5.56) than WPV non-exposed groups.

Conclusion: Nurses’ burnout could be decreased if issues like violence and bullying were addressed in the workplace. Hospital administrators, policymakers, and the government must all promote and implement an acceptable working environment.

Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are integral parts of the health system of any country. Among them, nurses are identified as the most responsible for the patients’ better prognosis. However, working place, in some cases, becomes an issue of their adverse mental health outcomes. Previously in several studies, workplace bullying (WPB) and workplace violence (WPV) were addressed to predict nurses’ burnout [1–5]. On the other hand, burnout always predicts adverse mental health outcomes [6]. Therefore, the nurses being fit both physically and mentally were encountered in numerous research [3, 7].

Burnout is the prolonged response due to long-standing interpersonal stressors. In the 1970s, this term was introduced by psychoanalyst Freudenberger [8], and this stress syndrome has subsequently been defined by Maslach as consisting of three qualitative dimensions, which are cynicism, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization that reduce the professional proficiency and personal accomplishment [9]. Suffering from burnout leads to less motivation which results in lower cognitive functions due to emotional exhaustion. Among health care workers, nurses are known to experience the symptoms of burnout more than others do, and this poses serious consequences for patients, other healthcare professionals, and healthcare institutions [10]. Nurses’ burnout is influenced by a multitude of factors such as work at night shifts, work-related stress, the number of days off, disagreements with co-workers or patients, as well as the connection between the nurse and their supervisor [11–13].

Workplace bullying (WPB) is defined as a pattern of offensive behavior by members of an organization, which often exacerbates in intensity with the endeavor to harm [14]. Employees perceive WPB when they become targeted and exposed to prolonged negative behaviors and cannot defend themselves [15]. WPB is significantly correlated with physical and emotional fatigue and is known as a tolerated issue in nursing [16]. Workplace bullying has a variety of negative consequences, ranging from low self-esteem to suicide [17, 18]. Furthermore, research found that several job-related problems such as lower job satisfaction, lower productivity, poor job performance, burnout, and an increased likelihood of employee turnover intent might be caused by workplace bullying [3]. Several studies investigated the occurrence of bullying and its potential consequences, particularly the relationship between workplace bullying and symptoms of burnout. The results indicated that burnout symptoms (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) were more common and higher among nurses who reported being bullied [6, 19].

Workplace violence (WPV) is defined as the use of force against another person or a group of individuals in the workplace that causes physical or psychological harm or even death [20]. WPV is the violent act such as physical or verbal assaults and threats of assault organized by someone at the workplace. It can be perpetrated by patients, families, and co-workers. The prevalence of WPV among healthcare workers is significantly high in Asian countries: 51% in Pakistan [21], 62% in China [22], and 63% in India [23]. Besides, it is not a new issue in Bangladesh that HCWs are subjected to WPB and WPV. A recent study carried out in Bangladesh reported that a high proportion of healthcare professionals (43%) experienced some form of WPV [24]. Several studies in many countries found a relationship between WPV and burnout among nurses [25–27]. Burnout is one of the mechanisms through which WPV may result in poor psychological and physical health outcomes among nurses.

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous incidents of violence, harassment, and stigmatization have been reported against healthcare employees, patients, and medical infrastructure; 67% of the reported incidents of violence and harassment were aimed at healthcare personnel [28]. These violent actions have been found to elevate stress levels and, as a result, intensify the psychological consequences resulting from moral injuries [29]. Besides, during COVID-19, a large number of HCWs experienced unfavorable mental health outcomes. Studies have demonstrated that nurses are more prone than doctors and other healthcare workers to WPV and WPB [30, 31]. A recent study conducted in Bangladesh among nurses to determine the mental health consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic reported that the prevalence of mild to extremely severe depression was 50.5%, anxiety was 51.8%, and stress was 41.7% [32].

The majority of reports on WPV, WPB, and healthcare personnel have appeared in the media through newspapers and electronic media in Bangladesh; however, there has not been any systematic research conducted to determine the true prevalence of WPV and WPB or the impacts that they have [33]. Moreover, while it is clear that HCWs experienced a higher level of bullying and violence during COVID-19 around the world, there are no substantial evidence-based findings on these workplace hazards and their impact on burnout among Bangladeshi nurses. Henceforth, we sought to examine the burnout among the nurses of Bangladesh and its predictive factors, in particular the association of workplace bullying and violence with burnout. This finding could serve as foundational information for establishing a healthy organizational culture within the nursing community, reducing the risk of burnout among clinical nurses.

Methods

Study Design and Settings

This was a cross-sectional study conducted among Bangladeshi registered nurses available on online platforms and the nurses working in eight tertiary level hospitals of two large administrative divisions (Dhaka and Sylhet) in Bangladesh. These two administrative divisions were conveniently selected because Dhaka is the capital and Sylhet is a significant region of Bangladesh. The self-reported data were collected between 26 February 2021 and 10 July 2021.

Participants

The study population of this study was all registered nurses of Bangladesh working in clinical settings for at least 1 year. Our required sample size was 1,024 at 80% power, 95% CI of 0.05 to 1.96, and 3% margin of error with an assumption that 50% of the nurses had symptoms of burnout. Finally, from 1,345 obtained responses, 1,264 completed responses were considered in the analysis. Thus, an additional 11% of participants (240) helped to reduce the study’s margin of error [34].

Data Collection Procedure

An online and offline method of data collection was approached in this study. A semi-structured self-response questionnaire was developed to gather data for this study’s findings. The questionnaire had five parts. On the front page, study’s objectives and the responding procedure were described. The first part of the questionnaire consisted of the demographic and occupational characteristics of the respondents. In the subsequent parts of the questionnaire, workplace bullying, violence, and burnout-related questions were documented with proper instructions for responding to them. Finally, three dichotomous-response (yes/no) questions related to participants’ “presence of enjoyment in the current job,” “presence of enthusiasm in the current job,” and “presence of satisfaction in the current job” were asked. The questionnaire was translated into Bangla with the help of an expert. One nurse superintendent of a tertiary hospital and one public health expert in Bangladesh reviewed the initial questionnaire. Based on their suggestions, modification of the questionnaire was performed. For online data collection, convenience and snowball-sampling methods were followed. At the time of the pandemic, face-to-face data collection was restricted. So, a questionnaire link (using “Google Form”) was distributed on common social media platforms used by nurses (Facebook, WhatsApp, etc.) in Bangladesh, and available registered nurses were invited to participate. By online method of data collection, 721 completed responses were obtained. To achieve the required sample size, we distributed another 700 printed questionnaires in eight hospitals in two geographical divisions (Dhaka and Sylhet) in Bangladesh. The respondents were provided with 7 days to respond to the questionnaire, and data collectors received questionnaires after 7 days. After receiving 655 returned copies, 543 were obtained as completed responses. Thus, a total of 1,264 completed responses were finally included in the current study.

Workplace Bullying Measure

The Short Negative Acts Questionnaire [S-NAQ] was used to determine workplace bullying exposure [35]. It comprises nine items that assess whether or not a person has been subjected to bullying behaviors in the last 6 months. The scale items address both the personal and work-related forms of bullying (e.g., “there has been gossip or rumors spread about you” and “necessary information was withheld that impeded your ability to do your job”). The answer categories ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 being “never” and 5 being “daily”. The S-NAQ has a good level of reliability and validity [35]. This scale has been used to measure bullying in numerous studies in several countries, including Belgium, Italy, and Norway [36–38]. The 9-item S-NAQ has a Cronbach's α of 0.89 in our current study. S-NAQ has two cut-off scores: 15 and 23, which means that respondents scoring less than 15 in the S-NAQ can be considered “non-exposed” to bullying at work; those scoring between 15 and 22 are at “high risk” of being bullying victims or may be immersed in a bullying process; whereas those scoring 23 or higher can be considered “targeted” of workplace bullying [39].

Workplace Violence Measure

The workplace violence scale (WVS) was used to measure the WPV experienced in the last 12 months [40, 41]. Several studies used this scale to measure workplace violence among nurses and other health care workers previously [42–45]. The scale was composed of five types of WPV named physical assault, emotional abuse, threat, verbal and sexual harassment, and sexual assault. The responses (score ranges from 0 to 3) of the five items scale indicate the frequencies of each type of WPV. Score 0 indicates WPV 0 time/none, 1 indicates 1 time, 2 indicates 2 or 3 times, and 3 indicates WPV more than 4 times. By summing all the responses, the total score ranged from 0 to 15. Four WPV categories were derived from scores 0 for none, 1 to 5 for low, 6 to 10 for intermediate, and 11 to 15 for high. In the questionnaire, participants were given specific definitions of each type of violence. Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient was calculated at 0.60, which indicated an acceptable internal consistency of the scale.

Burnout Measure

The 10-item Burnout Measure-Short version (BMS) developed by Malach-Pines was used in the last segment of our survey [46]. The BMS is a brief and easy-to-use tool to measure burnout. In this tool, an individual’s levels of physical exhaustion, emotional exhaustion, and mental exhaustion are assessed using the core elements of the concept of burnout in a series of 10 questions. Each item is graded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). For all 10 items, the total response points ranged from 10 to 70, based on the response value for each item. The overall burnout score for each participant was calculated by dividing the sum of each participant’s response values by 10. Thus, the overall burnout score ranged from 1 to 7. An overall score ≥4 indicates an established state of burnout, according to Malach-Pines. Therefore, individuals are divided into two categories based on their overall burnout score: those who are likely to experience burnout (overall score ≥4) and those who are not likely to experience burnout (overall score <4). The 10-item BMS was validated and used on different samples and has shown satisfactory psychometric properties [46–50]. In our study, the Cronbach’s α for the 10-item BMS was 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Data Analysis

The demographic profile and occupational characteristics of the study sample were described using descriptive statistics expressed in frequency and percentages. A chi-square test was performed for unadjusted associations. Mixed-effects Poisson regression models were fitted to find the adjusted association between burnout and WPB, WPV, and other study variables. The factors in the unadjusted test were included in the adjusted models at a priori specified p-value of 0.1. Mixed-effects Poisson regression models with robust error variance were used to avoid overestimation of associations with common binary outcomes measured in cross-sectional studies [51–53]. We fitted three models to investigate the adjusted association between the predictor variables and the outcome variable. Model 1 included only demographic variables. Model 2 included both demographic and occupational variables. Model 3 included all main-effects terms (demographic and occupational variables) and two-way interaction-effects terms between WPB and WPV. The findings were expressed as relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Moreover, the association between burnout and three job-related questions was evaluated using chi-square test. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical software STATA-16 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, United States) was used for data analysis.

Ethical Issue

The ethical review committee of Begum Rabeya Khatun Chowdhury Nursing College, Bangladesh (approval ID: BRKCNC-IRB-2021/5) approved this study involving human participants. On the first page of the questionnaire, the study’s aims and objectives were explained. The participation of respondents in the study defined their implied consent.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

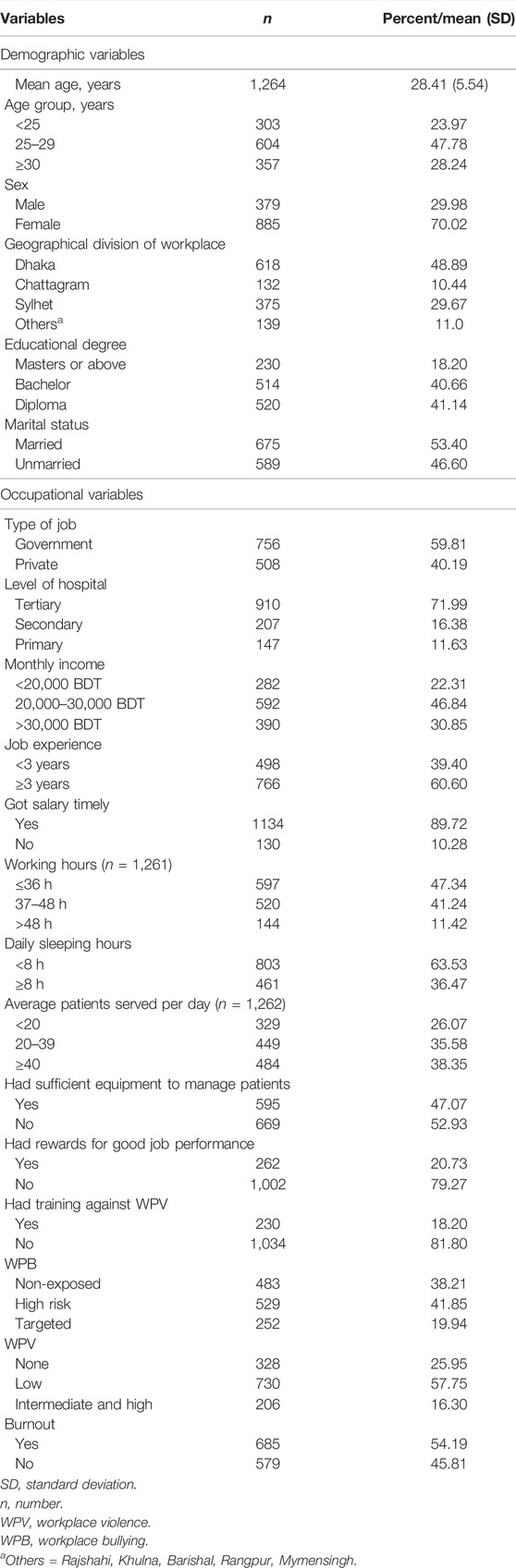

The characteristics of the 1,264 participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 28.41 (SD: 5.54), and 70.02% were female. The 756 (59.81%) nurses were involved in government hospitals, and the remaining 508 (40.19%) were in private hospitals. Moreover, 910 (71.99%) of the nurses were from tertiary care hospitals. More than half of the nurses (52.93%) reported that they did not have enough equipment to manage the patients while on the job. A substantial percentage of respondents (79.27%) stated that they had never been awarded for good work, and 81.80% of nurses stated that they had never been trained against WPV.

Prevalence of Burnout, Workplace Bullying, and Workplace Violence

Burnout was found to be prevalent in 685 (54.19%) of the 1264 nurses. Among the nurses, 781 (61.79%) reported workplace bullying (WPB), with 529 (41.85%) and 252 (19.94%) nurses reported “high risk bullying” and “targeted bullying,” respectively. According to the survey, 206 nurses (16.30%) reported “intermediate and high” levels of workplace violence during the last 12 months (Table 1).

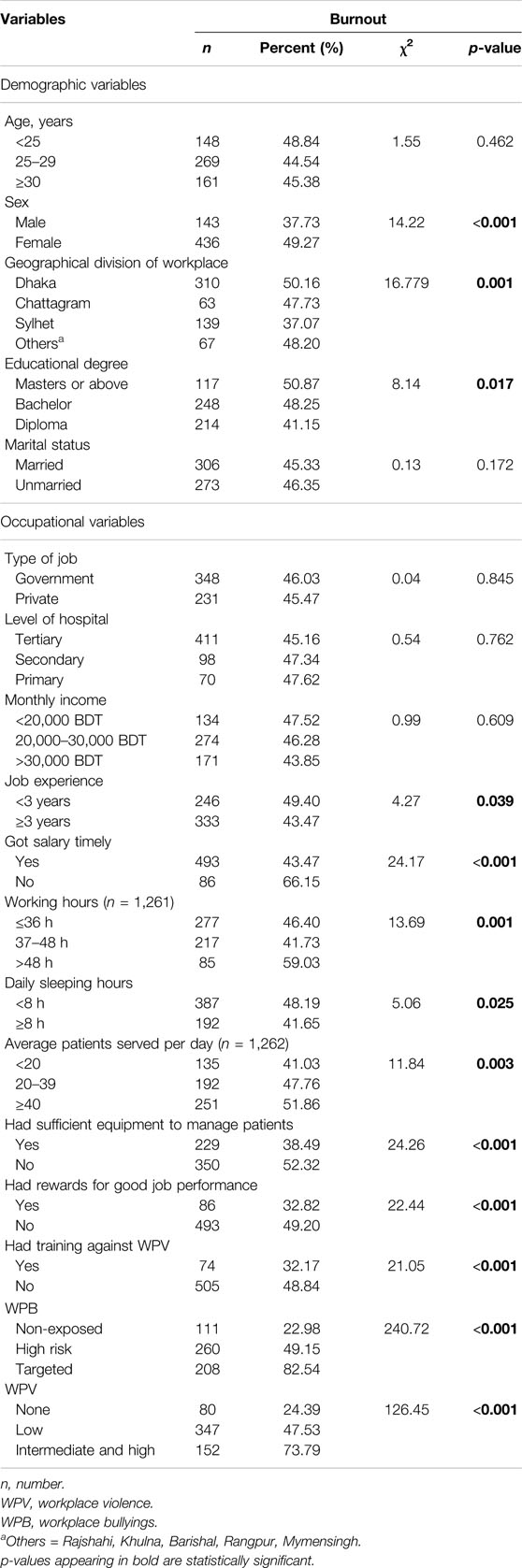

Unadjusted Association of Workplace Bullying and Workplace Violence with Burnout

Table 2 represents the burnout distribution as well as the unadjusted relationship between burnout and WPB, WPV, and other factors. In the chi-square test, WPB was found to be significantly associated with burnout of nurses (p < 0.001). Similarly, WPV was significantly associated with nurses’ burnout (p < 0.001). Almost half of the female nurses (49.27%) were found to be burnout. In demographic variables, sex, geographical division of workplace, and educational degree of the nurses were found to be significantly associated with burnout (p < 0.001). The occupational variables that were significantly associated with burnout were job experience of the nurses, timely salary, working hours, sleeping hours, number of patients dealt with per day, the sufficiency of the equipment to manage patients, rewards for good job performance, and training for the nurses against WPV (p < 0.001).

TABLE 2. Unadjusted association between burnout and workplace bullying, violence, and other study variables, Bangladesh, 2021 (n = 1,264).

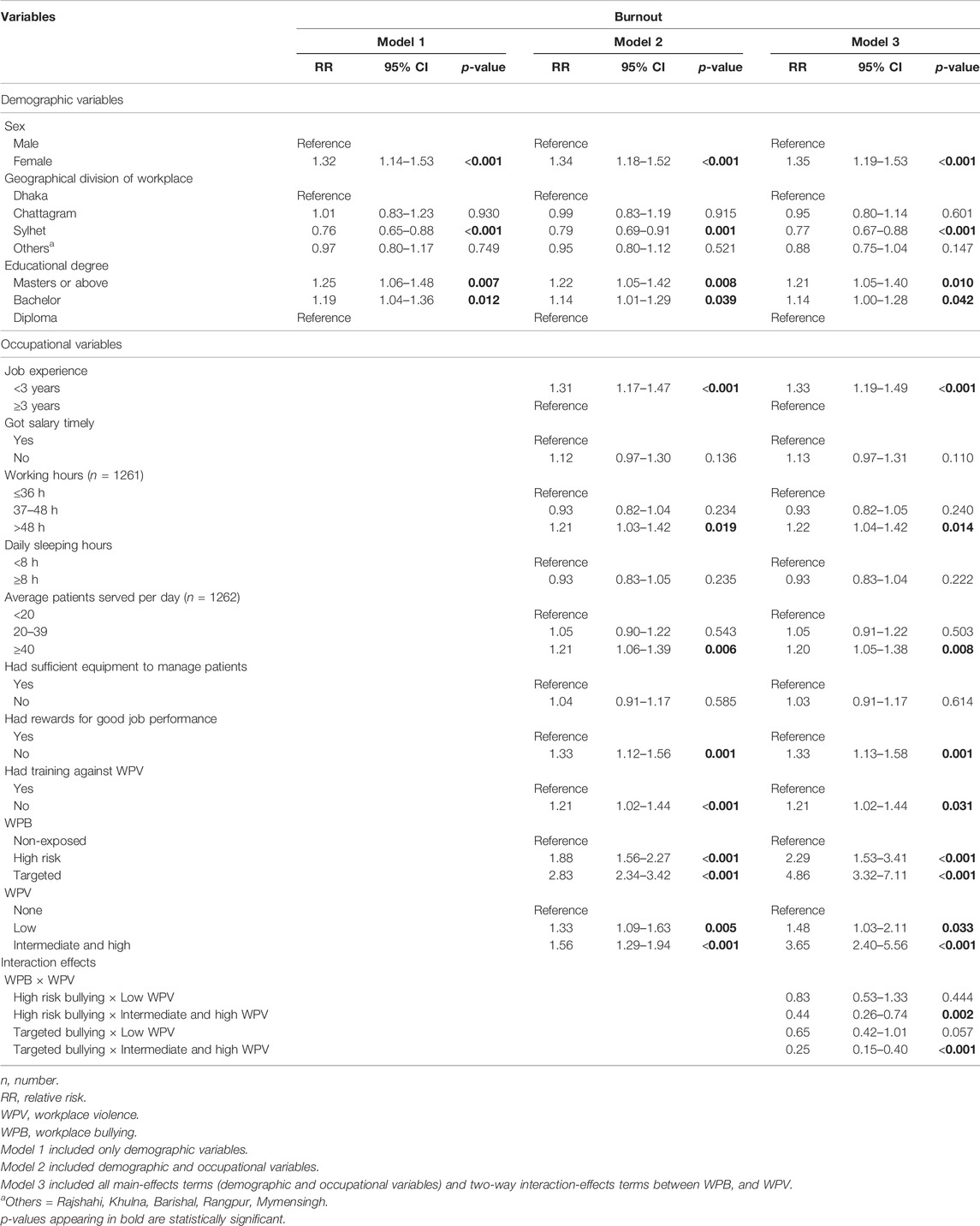

Adjusted Analysis: Mixed-Effects Poisson Regression Models

Table 3 represents the adjusted association of workplace bullying, burnout, demographic, and occupational factors with burnout identified from three mixed-effects Poisson regression models. According to Model 3, among the nurses, “high risk bullying” and “targeted bullying” were at 2.29 (95% CI: 1.53–3.41, p < 0.001) and 4.86 (95% CI: 3.32–7.11, p < 0.001) times more risk of burnout, respectively, compared to non-exposed groups to the bullying. The “low” and “intermediate and high” levels of WPV groups were 1.48 (95% CI: 1.03–2.11, p < 0.033) and 3.65 (95% CI: 2.40–5.56, p < 0.001) times more risk of being burnout, respectively, compared to WPV non-exposed groups. In terms of their association with burnout, WPB and WPV were found to interact with each other, as two combinations of WPB and WPV were significant (high risk bullying × intermediate and high WPV, p = 0.002 and targeted bullying × intermediate and high WPV, p < 0.001) compared with their respective reference combinations. Females were at 1.35 (95% CI: 1.19–1.53, p < 0.001) times more risk of burnout. Compared to the nurses who completed diploma educational degrees, the nurses who completed bachelor’s and master’s degrees were at 1.21 (95% CI: 1.05–1.40, p = 0.010) and 1.14 (95% CI: 1.00–1.28, p = 0.042) times more risk of being burnout, respectively. Less experienced (<3 years) nurses were at 1.33 (95% CI: 1.19–1.49, p < 0.001) times more risk of being burnout compared to the nurses with ≥3 years of job experience. Nurses with higher working hours (>48 h per week) were at 1.22 (95% CI: 1.04–1.42, p = 0.014) times more risk of being burnout than the nurses who worked ≤36 h per week. The nurses who served the highest number of patients (≥40 patients per day) were at 1.20 (95% CI: 1.05–1.38, p = 0.008) times more risk of being burnout than the nurses who served <20 patients per day. The nurses who usually did not get rewards from their authority for good job performance were at 1.33 (95% CI: 1.13–1.58, p = 0.001) times more risk of burnout than their counterparts. Nurses who did not receive any training against WPV were at 1.21 (95% CI: 1.02–1.44, p = 0.031) times more risk of burnout than their opposite parts.

TABLE 3. Mixed-effects Poisson regression models to find the adjusted association between burnout and workplace bullying, violence, and other study variables, Bangladesh, 2021 (n = 1,264).

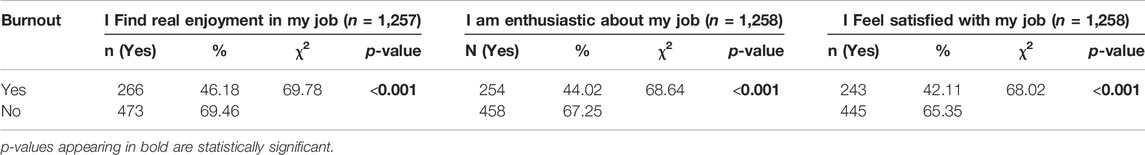

Association Between Burnout and Three Job-Related Questions

We asked nurses three job-related questions. Compared to the nurses who suffered burnout, non-burnout nurses found enjoyment in job (46.18% vs 69.46%, p < 0.001), were enthusiastic (44.02% vs 67.25%, p < 0.001), and satisfied (42.11% vs. 65.35%, p < 0.001) with their present job (Table 4).

Discussion

The current study investigated burnout among Bangladeshi nurses for the first time and its associated factors, including the roles of WPB and WPV on burnout. Several factors may influence healthcare workers’ physical, mental, and social health status in a lower-middle-income country.

This study found a high prevalence of burnout (54.19%) among Bangladeshi nurses. Previous research conducted in different settings found different degrees of burnout among the nurses. For instance, burnout was found among nurses in China at 25.01% [1], in Australia at 67% [2], and in Nigeria at 76% [54], measured by the same tool used in the current study. Our study suggests that the bullied nurses were at higher risk of burnout. Numerous studies reported that WPB was significantly associated with nurses’ burnout, supporting current study findings [3, 4, 6]. This study found that WPV-exposed nurses were at a greater risk of burnout. Similarly, Liu et al. [1], Duan et al. [5], and Hamdam et al. [55] reported a positive association between WPV and burnout. However, burnout may affect nurses’ mental health and elevate turnover intention, impeding better patient care [3]. Having had no training against WPV was also associated with nurses’ burnout. Therefore, appropriate managerial support, training, and leadership with fair and equitable distribution of facilities are needed to reduce violence and bullying in the workplace.

We did not find any significant association between the nurses’ age and burnout. This finding is supported by Liu et al.’s study finding [56]. However, Hayes et al. reported that the nurses of higher age with more working experience had a lower level of burnout [57]. We found that female nurses were more prone to burnout. Female nurses’ emotional labor as a caregiver may be a reason to perceive higher burnout than men [58]. However, few studies conducted in developed countries found no gender-based variations [3, 56]. Therefore, further gender perspective factors investigation is essential in the context of Bangladesh. Nurses from the Sylhet division, the northeastern part of Bangladesh, were more affected by burnout. Consistent with our findings, Hamdan et al. found burnout variations in the country’s different geographical locations [55]. In our study, the nurses who held higher educational degrees exerted a higher level of burnout. On the contrary, Zhang et al. found a negative correlation between higher degree education and burnout among Chinese nurses [59]. However, Liu et al. observed that educational degree does not arbitrate the burnout variations [56]. In Bangladesh, nursing is known to have less social recognition, payments, and work status and is recognized as a second segmental profession [60]. Our finding may be explained by the fact that nurses with high educational degrees remain more vulnerable to psychological suppression considering the social impression, minimal job promotion, or salary increments in the context of Bangladesh [32].

Among the occupational characteristics, the nurses with less duration of working experience had a higher level of burnout, supported by the finding of Kim et al. [3]. Other similar research also found a significant correlation between nurses’ years of experience and burnout [56, 61]. Evidence suggests that along with working experience increment, nurses achieve higher tolerances to overcome any adverse working situations [61]. Thus, the working experience might play a protective role against burnout. A higher working hour was associated with a higher level of nurses’ burnout. This finding is consistent with Hayes et al.’s research [57]. Similarly, Vandenbroeck et al. reported that more working hours indicate a higher workload that affects the nurses’ burnout [62]. The current study found that dealing with more patients was also associated with burnout. Evidence suggests that emotional exhaustion is emphasized by working hours or workload increments related to nurses’ insufficient professional efficacy [63]. Therefore, synergies between working hours and working load are needed to get a service-oriented nursing practice. Having had no arrangement of rewards for the nurses from the authority for good work performance was associated with a higher level of burnout. This finding might be explained by Hayes et al.’s and Vandenbroeck et al.’s study findings that reported a lack of support from co-workers and organizations strongly associated with burnout [57, 62]. Based on this study and the studies discussed, it can be concluded that to abate burnout, rewards for good job performance and keeping nurses in decision-making need to be prioritized.

In this study, the nurses who were not suffered from burnout were more satisfied, enjoyed, and enthusiastic with their present job than those who experienced burnout. Consistently, Roy et al. investigated Bangladeshi physicians’ burnout levels that significantly predicted their job satisfaction [64]. Similarly, Demerouti et al. reported that lower life satisfaction and enjoyment are strongly associated with nurses’ experiences of higher burnout [7]. The research findings expound that burnout can erase nurses’ working enjoyment, enthusiasm, and satisfaction.

Implications of the Findings

Nurses are the most important staff in a country’s healthcare system as they deal with the health and well-being of the patients. We anticipate that our study findings could help the authorities, the Directorate General of Health Services, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Directorate General of Nursing and Midwifery, Bangladesh to understand the workplace environment of nurses and take the necessary measures to reduce the frequency of workplace bullying and violence.

Strengths and Limitations

To our best knowledge, this is the first study that addressed Bangladeshi nurses’ burnout status and its associated factors, including the association with WPB and WPV. Nurses from all geographical divisions of the country got opportunities to participate in the study. The larger sample size might provide substantial accuracy to the study findings. However, this research had some limitations also. As a non-random sampling technique was applied, selection bias could not be excluded. The risk of information bias might be present due to the self-reported questionnaire. As a nature of a cross-sectional study, causality could not be established. However, we hope that the outcomes of our research will provide a succinct summary of the working environment of Bangladeshi nurses. Further in-depth and rigorous research is recommended focusing on nurses’ burnout, WPB, and WPV to establish sustained evidence to make nurses’ working environments safer.

Conclusion

A high prevalence of burnout, workplace violence, and bullying was found among Bangladeshi nurses. Workplace violence and bullying were also identified as potential predictors of burnout. Burnout is known to have a negative impact on job satisfaction, which leads to a higher likelihood of turnover in the workplace. As a result, establishing a safer working environment is critical, as is demanding improved nursing services. Thus, addressing the variables, enhancing the working environment for nurses, increasing job satisfaction, as well as lowering burnout, bullying, and workplace violence are crucial through support and the implementation of suitable policies from hospital administrators, policymakers, and the government.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The ethical review committee of Begum Rabeya Khatun Chowdhury Nursing College, Bangladesh (approval ID: BRKCNC-IRB-2021/5).

Author Contributions

Conceptualized the study: SRC, HK, and MRC. Contributed data extraction and analyses: SRC, HK, and MRC under the guidance of AH. Result interpretation: SRC and HK under the guidance of AH. Prepared the first draft: SRC and HK. Contributed during the conceptualization and interpretation of results and substantial revision: SRC, HK, and AH. Revised and finalized the final manuscript: SRC, HK, and AH. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All the authors would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the nurses who participated in this study. The authors also acknowledge Anjan Kumar Roy, Sabbir Mahmud, Lukman Hossain, Mohammad Toyabur Rahman Bhuya, Mahfuzur Rahman Chowdhury, and Samiul Amin Chowdhury for their valuable support during data collection.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604769/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Liu, J, Zheng, J, Liu, K, Liu, X, Wu, Y, Wang, J, et al. Workplace Violence against Nurses, Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and Patient Safety in Chinese Hospitals. Nurs Outlook (2019) 67:558–66. doi:10.1016/J.OUTLOOK.2019.04.006

2. Lang, M, Jones, L, Harvey, C, and Munday, J. Workplace Bullying, Burnout and Resilience Amongst Perioperative Nurses in Australia: A Descriptive Correlational Study. J Nurs Manag (2021) 30:1502–13. doi:10.1111/JONM.13437

3. Kim, Y, Lee, E, and Lee, H. Association between Workplace Bullying and Burnout, Professional Quality of Life, and Turnover Intention Among Clinical Nurses. PLoS One (2019) 14:e0226506. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0226506

4. Giorgi, G, Mancuso, S, Fiz Perez, F, Castiello D’Antonio, A, Mucci, N, Cupelli, V, et al. Bullying Among Nurses and its Relationship with Burnout and Organizational Climate. Int J Nurs Pract (2016) 22:160–8. doi:10.1111/IJN.12376

5. Duan, X, Ni, X, Shi, L, Zhang, L, Ye, Y, Mu, H, et al. The Impact of Workplace Violence on Job Satisfaction, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention: the Mediating Role of Social Support. Health Qual Life Outcomes (2019) 17:93. doi:10.1186/S12955-019-1164-3

6. Sá, L, and Fleming, M. Bullying, Burnout, and Mental Health Amongst Portuguese Nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2009) 29:411–26. doi:10.1080/01612840801904480

7. Demerouti, E, Bakker, AB, Nachreiner, F, and Schaufeli, WB. A Model of Burnout and Life Satisfaction Amongst Nurses. J Adv Nurs (2000) 32:454–64. doi:10.1046/J.1365-2648.2000.01496.X

8. Freudenberger, HJ. Staff Burn-Out. J Soc Issues (1974) 30:159–65. doi:10.1111/J.1540-4560.1974.TB00706.X

9. Maslach, C. Different Perspectives on Job Burnout. Contemp Psychol (2004) 49:168–70. doi:10.1037/004284

10. Kobayashi, Y, Oe, M, Ishida, T, Matsuoka, M, Chiba, H, and Uchimura, N. Workplace Violence and its Effects on Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress Among Mental Healthcare Nurses in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17:2747. doi:10.3390/IJERPH17082747

11. Ntantana, A, Matamis, D, Savvidou, S, Giannakou, M, Gouva, M, Nakos, G, et al. Burnout and Job Satisfaction of Intensive Care Personnel and the Relationship with Personality and Religious Traits: An Observational, Multicenter, Cross-Sectional Study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs (2017) 41:11–7. doi:10.1016/J.ICCN.2017.02.009

12. Vifladt, A, Simonsen, BO, Lydersen, S, and Farup, PG. The Association between Patient Safety Culture and Burnout and Sense of Coherence: A Cross-Sectional Study in Restructured and Not Restructured Intensive Care Units. Intensive Crit Care Nurs (2016) 36:26–34. doi:10.1016/J.ICCN.2016.03.004

13. Ramirez, AJ, Graham, J, Richards, MA, Cull, A, and Gregory, WM. Mental Health of Hospital Consultants: the Effects of Stress and Satisfaction at Work. Lancet (1996) 347:724–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90077-X

14. Einarsen, S, Hoel, H, and Cooper, C. Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice. 1st Edn. CRC Press. (2003). doi:10.1201/9780203164662

15. Einarsen, S, and Skogstad, A. Bullying at Work: Epidemiological Findings in Public and Private Organizations. Eur J Work Organ Psychol (2008) 5:185–201. doi:10.1080/13594329608414854

16. Wolf, LA, Perhats, C, Clark, PR, Moon, MD, and Zavotsky, KE. Workplace Bullying in Emergency Nursing: Development of a Grounded Theory Using Situational Analysis. Int Emerg Nurs (2018) 39:33–9. doi:10.1016/J.IENJ.2017.09.002

17. Randle, J. Bullying in the Nursing Profession. J Adv Nurs (2003) 43:395–401. doi:10.1046/J.1365-2648.2003.02728.X

18. Castronovo, MA, Pullizzi, A, and Evans, SK. Nurse Bullying: A Review and A Proposed Solution. Nurs Outlook (2016) 64:208–14. doi:10.1016/J.OUTLOOK.2015.11.008

19. Skogstad, A. Bullying, Burnout and Well-Being Among Assistant Nurses. Journal of Occupational Health and Safety - Australia and New Zealand. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/20424764/Bullying_burnout_and_well_being_among_assistant_nurses (Accessed November 17, 2021).

20. Ferri, P, Silvestri, M, Artoni, C, and di Lorenzo, R. Workplace Violence in Different Settings and Among Various Health Professionals in an Italian General Hospital: a Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol Res Behav Manag (2016) 9:263–75. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S114870

21. Khan, MN, Haq, ZU, Khan, M, Wali, S, Baddia, F, Rasul, S, et al. Prevalence and Determinants of Violence against Health Care in the Metropolitan City of Peshawar: a Cross Sectional Study. BMC Public Health (2021) 21:330–11. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10243-8

22. Lu, L, Dong, M, Wang, Sbin, Zhang, L, Ng, CH, Ungvari, GS, et al. Prevalence of Workplace Violence against Health-Care Professionals in China: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Observational Surveys. Trauma Violence Abuse (2020) 21:498–509. doi:10.1177/1524838018774429

23. Hossain, MM, Sharma, R, Tasnim, S, Kibria, GMal, Sultana, A, and Saxena, T. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Associated Factors of Workplace Violence against Healthcare Professionals in India: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.01.01.20016295

24. Shahjalal, M, Gow, J, Alam, MM, Ahmed, T, Chakma, SK, Mohsin, FM, et al. Workplace Violence Among Health Care Professionals in Public and Private Health Facilities in Bangladesh. Int J Public Health (2021) 66:115. doi:10.3389/ijph.2021.1604396

25. Khamisa, N, Peltzer, K, and Oldenburg, B. Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes Among Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2013) 10:2214–40. doi:10.3390/IJERPH10062214

26. Havaei, F, Astivia, OLO, and MacPhee, M. The Impact of Workplace Violence on Medical-Surgical Nurses’ Health Outcome: A Moderated Mediation Model of Work Environment Conditions and Burnout Using Secondary Data. Int J Nurs Stud (2020) 109:103666. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103666

27. Laschinger, HKS, and Grau, AL. The Influence of Personal Dispositional Factors and Organizational Resources on Workplace Violence, Burnout, and Health Outcomes in New Graduate Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Nurs Stud (2012) 49:282–91. doi:10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2011.09.004

28. Devi, S. COVID-19 Exacerbates Violence against Health Workers. Lancet (2020) 396:658. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31858-4

29. Brewis, A, Wutich, A, and Mahdavi, P. Stigma, Pandemics, and Human Biology: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Am J Hum Biol (2020) 32:e23480. doi:10.1002/AJHB.23480

30. Liu, J, Gan, Y, Jiang, H, Li, L, Dwyer, R, Lu, K, et al. Prevalence of Workplace Violence against Healthcare Workers: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Occup Environ Med (2019) 76:927–37. doi:10.1136/OEMED-2019-105849

31. Etienne, E. Exploring Workplace Bullying in Nursing. Workplace Health Saf (2014) 62:6–11. doi:10.1177/216507991406200102

32. Chowdhury, SR, Sunna, TC, Das, DC, Kabir, H, Hossain, A, Mahmud, S, et al. Mental Health Symptoms Among the Nurses of Bangladesh during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Middle East Curr Psychiatry (2021) 28:23–8. doi:10.1186/s43045-021-00103-x

33. Hasan, MI, Hassan, MZ, Bulbul, MMI, Joarder, T, and Chisti, MJ. Iceberg of Workplace Violence in Health Sector of Bangladesh. BMC Res Notes (2018) 11:702–6. doi:10.1186/s13104-018-3795-6

34. James, DE, Schraw, G, and Kuch, F. Using the Sampling Margin of Error to Assess the Interpretative Validity of Student Evaluations of Teaching. Assess Eval High Educ (2014) 40:1123–41. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.972338

35. Notelaers, G, van der Heijden, B, Hoel, H, and Einarsen, S. Measuring Bullying at Work with the Short-Negative Acts Questionnaire: Identification of Targets and Criterion Validity. Work Stress (2018) 33:58–75. doi:10.1080/02678373.2018.1457736

36. Balducci, C, Cecchin, M, and Fraccaroli, F. The Impact of Role Stressors on Workplace Bullying in Both Victims and Perpetrators, Controlling for Personal Vulnerability Factors: A Longitudinal Analysis. Work Stress (2012) 26:195–212. doi:10.1080/02678373.2012.714543

37. Hauge, LJ, Skogstad, A, and Einarsen, S. The Relative Impact of Workplace Bullying as a Social Stressor at Work. Scand J Psychol (2010) 51:426–33. doi:10.1111/J.1467-9450.2010.00813.X

38. Rodríguez-Muñoz, A, Baillien, E, de Witte, H, Moreno-Jiménez, B, and Pastor, JC. Cross-lagged Relationships between Workplace Bullying, Job Satisfaction and Engagement: Two Longitudinal Studies. Work Stress (2009) 23:225–43. doi:10.1080/02678370903227357

39. León-Pérez, JM, Sánchez-Iglesias, I, Rodríguez-Muñoz, A, and Notelaers, G. Cutoff Scores for Workplace Bullying: The Spanish Short-Negative Acts Questionnaire (S-NAQ). Psicothema (2019) 31:482–90. doi:10.7334/psicothema2019.137

40. Wu, S, Zhu, W, Li, H, Lin, S, Chai, W, and Wang, X. Workplace Violence and Influencing Factors Among Medical Professionals in China. Am J Ind Med (2012) 55:1000–8. doi:10.1002/AJIM.22097

41. Hesketh, KL, Duncan, SM, Estabrooks, CA, Reimer, MA, Giovannetti, P, Hyndman, K, et al. Workplace Violence in Alberta and British Columbia Hospitals. Health Policy (2003) 63:311–21. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00142-2

42. Tian, Y, Yue, Y, Wang, J, Luo, T, Li, Y, and Zhou, J. Workplace Violence against Hospital Healthcare Workers in China: A National WeChat-Based Survey. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:582–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08708-3

43. Wang, P-X, Wang, M, Hu, G, and Wang, Z. [Study on the Relationship between Workplace Violence and Work Ability Among Health Care Professionals in Shangqiu City]. Shangqiu City (2006) 35:472–4.

44. Xie, XM, Zhao, YJ, An, FR, Zhang, QE, Yu, HY, Yuan, Z, et al. Workplace Violence and its Association with Quality of Life Among Mental Health Professionals in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Psychiatr Res (2021) 135:289–93. doi:10.1016/J.JPSYCHIRES.2021.01.023

45. Kabir, H, Chowdhury, SR, Tonmon, TT, Roy, AK, Akter, S, Bhuya, MTR, et al. Workplace Violence and Turnover Intention Among the Bangladeshi Female Nurses after a Year of Pandemic: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. In: Mdel M Pastor Bravo, editor, 2 (2022). p. e0000187. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PGPH.0000187PLOS Glob Public Health

46. Malach-Pines, A. The Burnout Measure, Short Version. Int J Stress Manag (2005) 12:78–88. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78

47. Alrawashdeh, HM, Al-Tammemi, AB, Alzawahreh, MK, Al-Tamimi, A, Elkholy, M, al Sarireh, F, et al. Occupational Burnout and Job Satisfaction Among Physicians in Times of COVID-19 Crisis: a Convergent Parallel Mixed-Method Study. BMC Public Health (2021) 21:811. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10897-4

48. Ayaz-Alkaya, S, Yaman-Sözbir, Ş, and Bayrak-Kahraman, B. The Effect of Nursing Internship Program on Burnout and Professional Commitment. Nurse Educ Today (2018) 68:19–22. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.05.020

49. Hong, E, and Lee, YS. The Mediating Effect of Emotional Intelligence between Emotional Labour, Job Stress, Burnout and Nurses’ Turnover Intention. Int J Nurs Pract (2016) 22:625–32. doi:10.1111/ijn.12493

50. Labrague, L, McEnroe-Petitte, D, Gloe, D, Tsaras, K, Arteche, D, and Maldia, F. Organizational Politics, Nurses’ Stress, Burnout Levels, Turnover Intention and Job Satisfaction. 2016.

51. Rana, J, Uddin, J, Peltier, R, and Oulhote, Y. Associations between Indoor Air Pollution and Acute Respiratory Infections Among Under-five Children in Afghanistan: Do SES and Sex Matter? Int J Environ Res Public Health (2019) 16:E2910. doi:10.3390/IJERPH16162910

52. Rana, J, Islam, RM, Khan, MN, Aliani, R, and Oulhote, Y. Association between Household Air Pollution and Child Mortality in Myanmar Using a Multilevel Mixed-Effects Poisson Regression with Robust Variance. Sci Rep (2021) 11:12983. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92193-0

53. Barros, AJD, and Hirakata, VN. Alternatives for Logistic Regression in Cross-Sectional Studies: An Empirical Comparison of Models that Directly Estimate the Prevalence Ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol (2003) 3:21–13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-3-21

54. Alabi, MA, Ishola, AG, Onibokun, AC, and Lasebikan, VO. Burnout and Quality of Life Among Nurses Working in Selected Mental Health Institutions in South West Nigeria. Afr Health Sci (2021) 21:1428–39. doi:10.4314/ahs.v21i3.54

55. Hamdan, M, and Hamra, AA. Burnout Among Workers in Emergency Departments in Palestinian Hospitals: Prevalence and Associated Factors. BMC Health Serv Res (2017) 17:407–7. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2356-3

56. Liu, W, Zhao, S, Shi, L, Zhang, Z, Liu, X, Li, L, et al. Workplace Violence, Job Satisfaction, Burnout, Perceived Organisational Support and Their Effects on Turnover Intention Among Chinese Nurses in Tertiary Hospitals: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open (2018) 8:e019525. doi:10.1136/BMJOPEN-2017-019525

57. Hayes, B, Douglas, C, and Bonner, A. Work Environment, Job Satisfaction, Stress and Burnout Among Haemodialysis Nurses. J Nurs Manag (2015) 23:588–98. doi:10.1111/JONM.12184

58. Li, M, Liu, J, Zheng, J, Liu, K, Wang, J, Miner Ross, A, et al. The Relationship of Workplace Violence and Nurse Outcomes: Gender Difference Study on a Propensity Score Matched Sample. J Adv Nurs (2020) 76:600–10. doi:10.1111/JAN.14268

59. Zhang, W, Miao, R, Tang, J, Su, Q, Aung, LHH, Pi, H, et al. Burnout in Nurses Working in China: A National Questionnaire Survey. Int J Nurs Pract (2020) 27:e12908. doi:10.1111/IJN.12908cited Nov 19, 2021)

60.Nursing profession needs reforms | (2021). theindependentbd.com. Available from: https://m.theindependentbd.com/post/203976 [Accessed November 19, 2021].

61.Job burnout in psychiatric and medical nurses in Isfahan. Islamic Republic of Iran (2021). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/117134 [Accessed November 19, 2021].

62. Vandenbroeck, S, van Gerven, E, de Witte, H, Vanhaecht, K, and Godderis, L. Burnout in Belgian Physicians and Nurses. Occup Med (Chic Ill (2017) 67:546–54. doi:10.1093/OCCMED/KQX126

63. Greenglass, ER, Burke, RJ, and Fiksenbaum, L. Workload and Burnout in Nurses. J Community Appl Soc Psychol (2001) 11:211–5. doi:10.1002/CASP.614

Keywords: burnout, COVID-19, nurses, Bangladesh, workplace violence, workplace bullying

Citation: Chowdhury SR, Kabir H, Chowdhury MR and Hossain A (2022) Workplace Bullying and Violence on Burnout Among Bangladeshi Registered Nurses: A Survey Following a Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Public Health 67:1604769. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604769

Received: 13 January 2022; Accepted: 06 October 2022;

Published: 17 October 2022.

Edited by:

Nino Kuenzli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), SwitzerlandCopyright © 2022 Chowdhury, Kabir, Chowdhury and Hossain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saifur Rahman Chowdhury, chowdhury.saifurrahman@northsouth.edu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Health in all Sustainable Development Goals”

Saifur Rahman Chowdhury

Saifur Rahman Chowdhury