- 1Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2School of Public Health and Institute of Child and Adolescent Health, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

Objectives: This study aimed to examine the association between early life famine exposure and adulthood cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) risk.

Methods: A total of 5,504 subjects were selected using their birthdate from national baseline data of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey to analyze the association between famine exposure in early life and CVDs risk in adulthood. CVDs was defined based on the self-reported doctor’s diagnosis.

Results: The prevalence of CVDs in the unexposed group, fetal-exposed, infant-exposed, and preschool-exposed groups was 15.0%, 18.0%, 21.0%, and 18.3%, respectively. Compared with the unexposed group, fetal-exposed, infant-exposed and preschool-exposed groups had higher CVDs risk in adulthood (p < 0.05). Compared with the age-matched control group, infancy exposed to famine had a significantly higher adulthood CVDs risk (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.15, 2.01; p = 0.006). The association seems to be stronger among population with higher education level (Pinteraction = 0.043). Sensitivity analysis revealed consistent association between early-life famine exposure and adult CVDs risk.

Conclusion: Early life exposed to the China great famine may elevate the risk of CVDs in adulthood.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) is the leading cause of mortality both in high-income countries and developing countries [1]. In China, cardiovascular deaths has accounted for 45% and 43% of total deaths in rural and urban areas, respectively [2]. The burden of CVDs is increasing and has become a major public health problem affecting 290 million people in China [3]. The emerging epidemic of CVDs in China was explained by urbanization, lifestyle changes, and the accelerated population aging, but now increasing attention is being paid to severe early-life malnutrition of the generation who born during “1959–1961 China Great famine” [4].

From the spring of 1959 to the fall of 1961, China experienced three years of extreme food shortages. This event is known as the “Three-year natural disaster” or “China’s Great famine”, which affected 600 million Chinese, resulted in approximately thirty million premature deaths, and the same number of births were lost or postponed, most of them died from hunger-related causes [5]. The survivors born during that period have reached their late 50s.

Developmental Origins of Health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, since reported firstly by professor David Barker in 1986, has become well accepted among scientists and researchers in medical and biological sciences [6]. Briefly, the hypothesis speculated that malnutrition in early life increased the risk of various non-communicable diseases in later life [7, 8]. Despite evidences from animal models suggested that poor nutrition condition in early life elevated the risk of adverse health outcome [9], direct evidence in human is still limited due to ethnical limitations. Existing studies in human mainly came from several natural history famine birth cohorts, such as Dutch Winter famine [10], 1959–1961 China Great famine [11].

In the past few decades, a rapid increasing number of studies have observed that early-life exposed to the 1959–1961 China Great famine is associated with the elevated risk of hypertension [12], diabetes [13], metabolic syndrome [14], dyslipidemia [15], chronic lung disease [16], and arthritis in later life [17]. These associations were further supported by our recently epigenetic findings, which showed that early-life exposure to the 1959–1961 China Great famine is associated with higher methylation level in the INSR and IGF2 genes and higher total cholesterol [18, 19].

However, the association between famine exposure in early life and risk of CVDs in later life remains unclear. In the Dutch famine cohort, Roseboom et al showed that the association of famine exposure with coronary heart disease risk was stronger in early gestation than that in mid or late gestation [20]. However, results from a cohort of the siege of Leningrad did not observe a direct effect of early-life famine on the prevalence of CVD [21]. Moreover, Ekamper et al did not found a significant association between prenatal famine exposure and CVD risk [22]. Several studies from the Chinese famine in 1959–1961 suggested that early-life famine exposure could strengthen the association between hyperglycemia, hypertension, diabetes, hyperglycaemia and CVDs [23–25], however, these studies did not examine the association of the Chinese famine exposure with CVD risk. Moreover, Du et al observed that early-life famine exposure elevated the risk of CVD in later life [26]. The Chinese famine occurred between 1959 and 1961, but Du et al defined participants who born between January 1, 1959 and December 31, 1962 as fetal exposed group. Thus, some participants might be not exposed to famine in their fetal period, which might underestimate the effect of famine exposure on CVDs.

In this context, the current study aims to explore the association between exposure to famine in several early life stages (prenatal, infant, and preschool) and CVDs risk in adulthood using data from the baseline survey of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS).

Methods

Participants

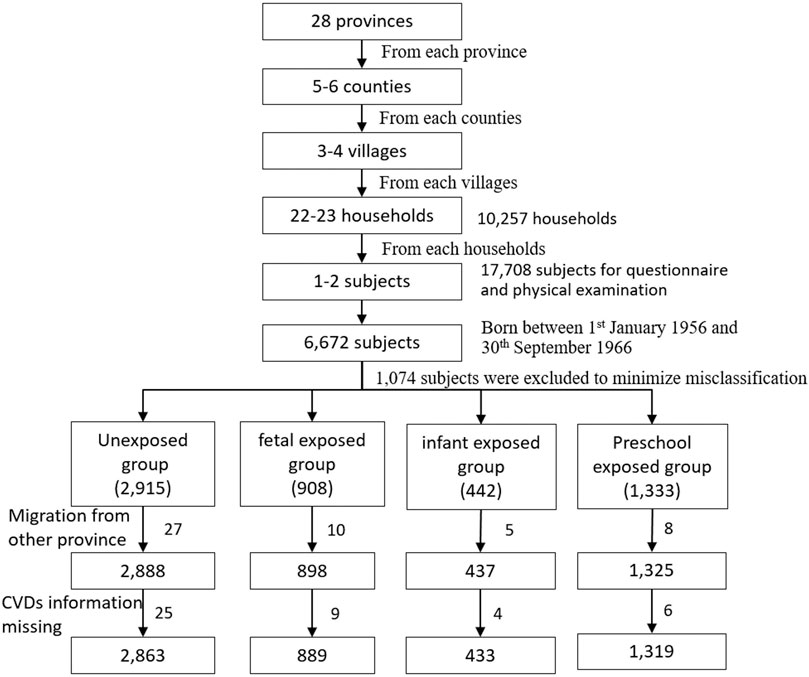

All the participants were selected from national baseline survey of the CHARLS program. It is a large national epidemiological program performed by the National School of Development in Peking University. The program focused on the health and retirement of middle and older adults aged ≥45 years. The detailed protocol had published elsewhere [27]. Briefly, the national baseline data were collected using the face-to-face household interview by trained interviewers in 28 provinces in mainland China from June 2011 to March 2012. The multi-stages cluster random sampling method was used to select the subjects from 10,257 households, 450 villages/neighborhoods, 150 counties, 28 provinces. Finally, 17,708 subjects were recruited in the baseline survey. Health status and function information was collected using a structured questionnaire. In the current study, we firstly selected 6,672 subjects born between January 1, 1956 and September 30, 1966. To minimize misclassification, we excluded 439 subjects born from January 1, 1959 to September 30, 1959, and 635 subjects born from October 1, 1961 to September 30, 1962. Furthermore, after excluding 50 subjects with migrating from another province to the current province of residence and 44 subjects without CVDs information, 5,504 subjects with complete self-reported CVDs information were selected in the final analysis (Figure 1). In addition, we excluded 1,636 subjects born between October 1, 1962 and September 30, 1964 from unexposed group to perform the sensitivity analysis.

Ethics Approval Statement

The current study is a secondary analysis of the CHARLS public data, which have been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–11015).

Definitions of Famine Exposure Groups and Severity

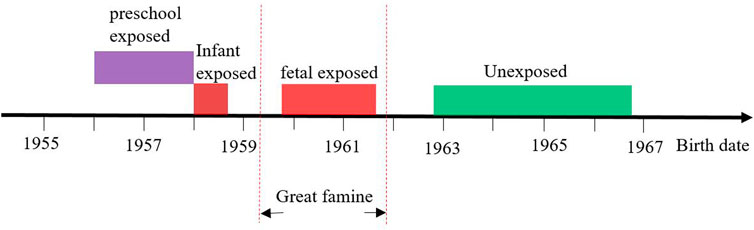

Considering the China Great famine lasted for three years from the spring of 1959 to the fall of 1961, and almost affected all Chinese lived in mainland China, the current study used birthdate of subjects to define famine exposed groups and unexposed groups (Figure 2). Preschool-exposed group (01/Jan/1956–31/Dec/1957), infant-exposed group (01/Jan/1958–30/Sep/1958), fetal-exposed group (1/Oct/1959–30/Sep/1961), and unexposed group 1 (1/Oct/1962–30/Sep/1966).

FIGURE 2. The definition of different famine exposure group according to date of birth (China, 2011–2012).

Although the China Great famine affected almost the entire region of mainland China, the severity of famine exposure varied across provinces due to different climate, agriculture policies and grain distribution system during famine period. Same as the previous study, [28], the excess mortality was used to reflect the severity of famine exposure due to lack of objective indicators such as daily calorie intake. The excess mortality was calculated using the formula listed below:

The range of excess mortality across China mainland was great, from 11.4% in Tianjin to 474.9% in Anhui province. The 50.0% was used as a threshold to categorize all the region into severe affected areas (excess mortality ≥50.0%) and less severe affected areas (excess mortality <50.0%).

Definition of Cardiovascular Diseases

CVDs was defined based on self-reported information in the current study. Subjects were defined as CVDs if he/she had been diagnosed with stroke or cardiac diseases (including heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems, such as chest pains when climbing stairs/uphill or walking quickly) by a doctor. Previous studies have showed that self-reported CVDs is relatively reliable [29, 30].

Covariates

General demographic, socioeconomic and lifestyle factors was collected using the structured national baseline questionnaire according to a standard procedure. The highest education attainments of subjects and their parents were categorized into four groups: primary school and below, junior school, senior school, college and above. The international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF) [31] was used to assess the physical activity (PA) level of and all subjects were categorized into light PA, moderate/vigorous PA groups. According to the alcohol use information, all the subjects were classified into former/current drinker (subjects who ever or current drank at least one-unit alcohol per month), and never drinker (subjects who never consumed alcohol in their life). According to smoking status, all the subjects were categorized into former/current smoker (subjects who ever or current smoked at least one cigarette in the past year), and never smoker (subjects who smoked less than 100 cigarettes in lifetime). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight (kg) divided by height square (m2), and subjects were defined as overweight/obese (if BMI ≥24.0 kg/m2) and normal weight (if BMI <24.0 kg/m2).

Statistical Analyses

The chi-square test and ANOVA were used to compare the difference between famine exposed groups and unexposed group of categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. Logistic regression model was used to analyze the association between famine exposure in early life and CVDs risk in adulthood. Model 1, unadjusted for any covariate. Model 2, adjusted for gender, Model three further adjusted for smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, education level, parent’s education level, BMI status, and famine severity.

To minimize the effect of age difference on the association between famine exposure and risk of CVDs, we combined the unexposed and preschool exposed groups as age-matched control group, and used the age-matched control group as a reference group to analyze the association between fetal and infant exposed groups and CVDs risk in adulthood.

In addition, we also performed a sensitivity analysis after excluding subjects born between October 1st, 1962 and September 30th, 1964 from unexposed group.

All analyses were performed by SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was considered to be when p < 0.05 (two sided).

Patient and Public Involvement

The patients and the public were not involved in the design of this study, in the selection of the outcomes, in the conduct of the study or in result dissemination.

Results

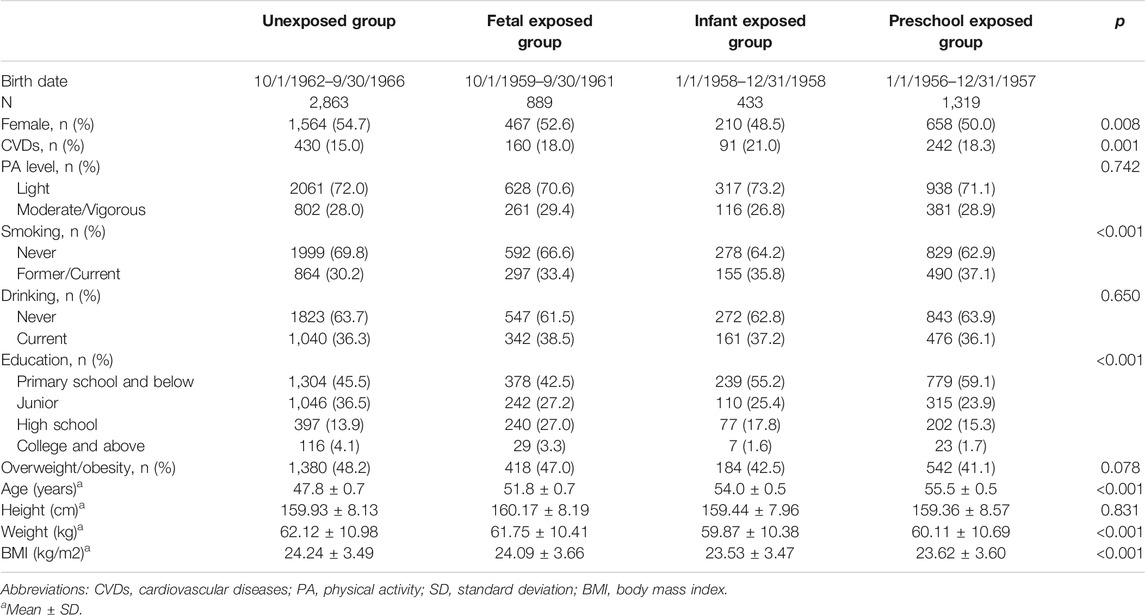

Basic characteristics are presented in Table 1. A total of 5,504 subjects with complete self-reported CVDs information were enrolled in the current study. The prevalence of CVDs in the unexposed group, fetal-exposed, infant-exposed, and preschool-exposed group was 15.0%, 18.0%, 21.0%, and 18.3%, respectively. Compared with the unexposed group, fetal-exposed, infant-exposed and preschool exposed groups had higher prevalence of CVDs (p = 0.001). The mean age of three famine-exposed groups was older than the unexposed group (p < 0.001). Compared with the unexposed group, infant-exposed and preschool-exposed groups had lighter weight (p < 0.05), and preschool-exposed group had smaller BMI (p = 0.006). In addition, distributions of gender, smoking status and education level of subjects were significant different among four groups (p < 0.05). However, we did not observe any difference for height, physical activity level, drinking status, and overweight/obese among four groups (p > 0.05).

TABLE 1. Basic characteristic of study population according to the China famine exposure (China, 2011–2012).

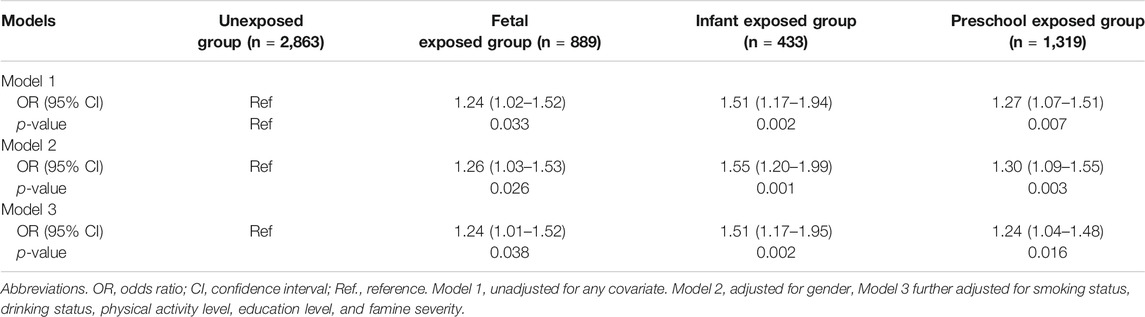

Table 2 shows the association between famine exposure in early life and risk of CVDs in adulthood. Compared with the unexposed group, fetal-exposed, infant-exposed and preschool-exposed groups had higher risk of CVDs in adulthood (p < 0.05), even after adjusting for gender (p < 0.05), and smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, the highest education attainment, BMI status, and famine severity (p < 0.05). Furthermore, sensitivity analysis also shows similar association (Supplementary Table S1).

TABLE 2. Associations between famine exposure and cardiovascular diseases risk, odds ratio (95% confidence interval) (China, 2011–2012).

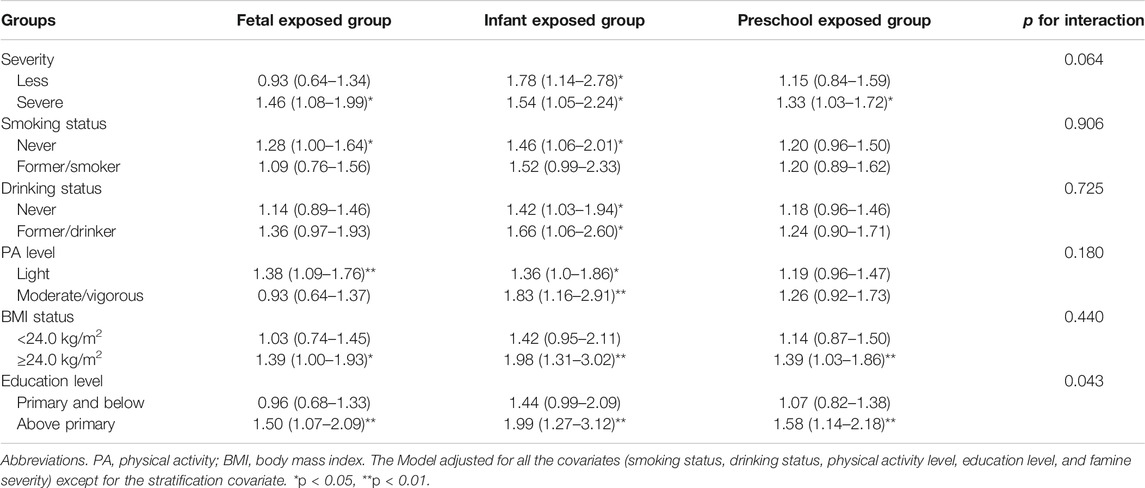

Associations between famine exposure and CVDs risk stratified by smoking status, drinking status, PA level, BMI status, and education level were presented in Table 3. The association between famine exposure and adulthood CVDs was not significantly modified by smoking status, drink behavior, and overweight/obesity status (p-values for interaction all >0.05). However, it seems that participants with above primary education level were more sensitive to early life famine exposure than that below primary education level (Pinteraction = 0.043). In addition, sensitivity analysis also shows similar association (Supplementary Table S2).

TABLE 3. Associations between famine exposure and cardiovascular diseases risk, odds ratio (95% confidence interval) stratified by smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, body mass index, and education level (China, 2011–2012).

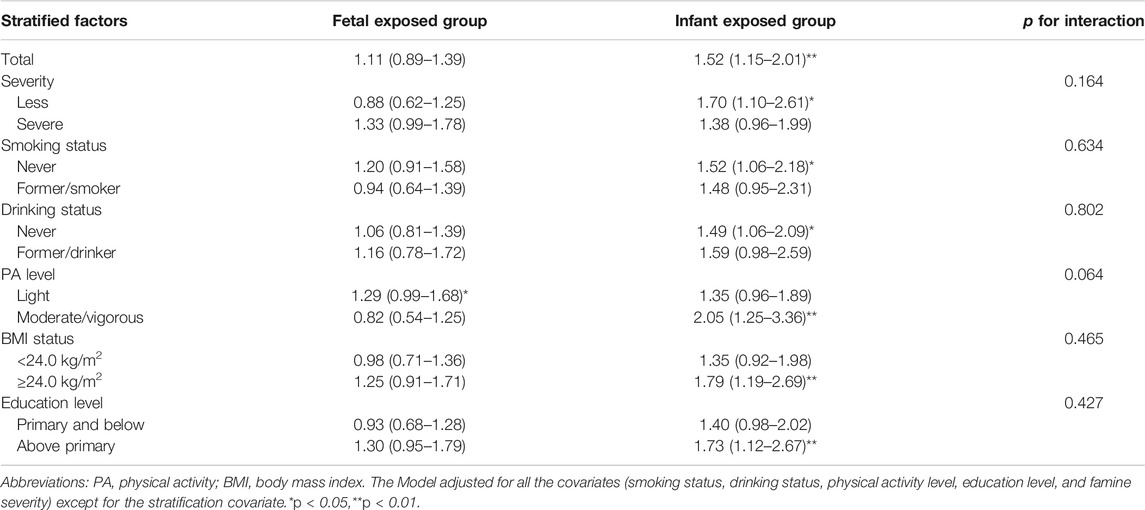

Table 4 shows the association between fetus and infancy famine exposure and CVDs risk in adulthood compared with age-matched control groups. Compared with the age-matched control group, fetal exposed group did not significantly increase adult CVDs risk (p > 0.05). However, infant exposed group still had a significantly higher risk of CVDs (OR = 1.52; 95% CI: 1.15, 2.01; p = 0.006). The association between famine exposure and adulthood CVDs was not significantly modified by smoking status, drink behavior, overweight/obesity status, and educational level (p-values for interaction all >0.05). Additionally, sensitivity analysis also shows similar association (Supplementary Table S3).

TABLE 4. Associations [odds ratio (95% confidence interval)] between fetus and infancy Chinese famine exposure and cardiovascular diseases risk compared with age-matched control groups (China, 2011–2012).

Discussion

We observed that infants exposed to severe famine significantly increased CVDs risk in adulthood, even compared to age-matched control. In addition, the association among subjects above primary education level appear to be stronger than that below primary education level. Indicating that early famine experienced may be responsible for the CVDs increasing in China, and a later ‘richer’ nutrition condition could exacerbate the effect.

Though the mechanisms that underlie the association between infancy famine exposure and adulthood CVDs risk yet to be elucidated, several potential mechanisms might contribute to the association. First, individuals who suffered from severe intrauterine malnutrition may increase the intake of a high-fat diet in adulthood while reducing the level of physical activity, as observed by a Dutch famine study [32]. Both high-fat foods and low physical activity are associated with the higher CVDs risk [33, 34]. However, we did not observe significant low PA among famine exposure groups (Table 1), suggesting low PA might not be that important in famine-CVDs association. Second, experience of famine during infanthood may alter the expression of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), subsequently alter the renal vascular and tubular structures, and increase the risk of hypertension in adulthood, as suggested by animal studies [35, 36]. Third, the changed DNA methylation level of cardiovascular metabolic genes may play a key role in association between famine exposure in early life and adulthood CVDs risk. Our previous findings have showed that fetus famine exposure was associated with higher DNA methylation of INSR and IGF2 genes, which were also linked with lipid indicators [18, 19].

In the current study, we observed that infants exposed to the famine increased 52% CVDs risk in adulthood. It was inconsistent with previous results from the Leningrad famine and the Dutch famine, which did not observe significant difference of CVDs prevalence between early-life famine exposed groups and unexposed group [21, 22, 37]. Despite that the Dutch famine found no increase in prevalence and mortality from cardiovascular disease after prenatal famine exposure [22, 37], they reported that adolescents who exposed to the Dutch famine had a significantly higher CHD risk in adulthood among women. However, children (0–9 years) exposed to the famine did not increase the risk of CHD in adulthood [38]. In addition, they did not observe significant association between famine exposure and stroke [39]. We speculated that severity and lasting time of famine exposure among the Leningrad famine, Dutch famine and China Great famine might contribute to the inconsistent association. The China Great famine affected about 600 million population, lasting for three years and lead to approximately 30 million premature deaths [40, 41]. However, the Leningrad famine only affected 2.9 million people (including 500,000 children), and 630,000 died from hunger-related causes, and the Dutch famine only lasted for 6 months [42].

The current study used the nationally representative data found that infancy exposed to the China Great famine was associated with CVDs risk in adulthood, and the association seems to be stronger in population above primary education level. We observed that subjects above primary education level had a significantly higher CVDs risk associated with infant famine exposure than that below primary education level (OR 1.44 vs. 1.99; Pinteraction = 0.043). Higher education attainments is associated with a higher income and richer nutrition condition in later life. Thus, the poor intrauterine nutrition condition mismatch with the richer nutrition condition in later life might furthermore exacerbate the adverse effect of famine exposure in early life on CVDs in adulthood. Despite we did not observe the significant interaction between famine exposure and BMI status on CVDs risk, the association between early-life famine exposure and adult CVDs risk seems to be stronger in subjects with BMI ≥24.0 kg/m2 than that with BMI <24.0 kg/m2.

The present study used the large national epidemiological survey data observed that infancy famine exposure was associated with higher CVDs risk in adulthood, and the association seems to be stronger among population above primary education level. However, several limitations should be mentioned. Firstly, despite we adjusted for the effect of age gap between exposed group and unexposed group using the age-matched control group, we cannot separate completely the effect of age gap from famine exposure. Secondly, the selection bias is unavoidable. Severe famine exposure in early life could eliminate weaker participants and remained healthier participants, which may decrease the real effect of famine exposure. Thirdly, CVDs was defined based on self-reported information and had not been validated by a sub-sample of the population studied, which might suffer from recall errors and misclassification of CVDs. However, the non-differential misclassification is likely to lead to an underestimated association. Fourth, subjects who exposed to famine in fetal period may also experience actual exposure in infant period partly due to China Great famine lasting for three years. There was no good method to distinguish accurately whether they were fetal-exposed or infant-exposed to famine. However, the current study defined infant-exposed cohort born from January 1, 1958 to December 31, 1958, which insured almost all the participants in this group were exposed to famine in infanthood. Fifth, due to adjustments to the limiting factors of CVDs, such as maternal kidney function and serum uric acid, the study might still have confounding bias.

Conclusion

Early-life exposure to the China great famine might elevated the risk of CVDs in adulthood. The famine-CVDs association might be modified by later higher education attainments.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN/page/data/2011-charls-wave1.

Ethics Statement

The current study is a secondary analysis of the CHARLS public data, which have been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–11015). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed significantly the paper, ZW, ZZ and contributed to conception and design. YD, XW, YL, and ZW carried out the initial analysis. RX, YD, and ZZ critically revised manuscript. ZW, XW, and YL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No: 81402692) awarded to Zhiyong Zou.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the CHARLS team for sharing the data and providing the sample training on data using. The authors also thank all the interviewers who participants the project.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2021.603859/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Jagannathan, R, Patel, SA, Ali, MK, and Narayan, KMV Global updates on cardiovascular disease mortality trends and attribution of traditional risk factors. Curr Diab Rep (2019). 19(7):44. doi:10.1007/s11892-019-1161-2

2. Chen, WW, Gao, RL, Liu, LS, Zhu, ML, Wang, W, Wang, YJ, et al. China cardiovascular diseases report 2015: a summary. J Geriatr Cardiol (2017). 14(1):1–10. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.01.012

3. Hu, S, Gao, R, Liu, L, Zhu, M, Wang, W, Wang, Y, et al. Summary of the 2018 report on cardiovascular diseases in China. Chin Circ J (2019). 3(34):209–20. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.03.001

4. Bruno, RM, Faconti, L, Taddei, S, and Ghiadoni, L Birth weight and arterial hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol (2015). 30(4):398–402. doi:10.1097/HCO.0000000000000180

5. Smil, V China's great famine: 40 years later. BMJ (1999). 319(7225):1619–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619

6. Barker, DJ, and Osmond, C Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet (1986). 1(8489):1077–81. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1

7. Barker, DJ The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med (2007). 261(5):412–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01809.x

8. Dobbing, J Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet (1993). 341(8857):1421–2. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)90995-S

9. Lillycrop, KA, Phillips, ES, Torrens, C, Hanson, MA, Jackson, AA, and Burdge, GC Feeding pregnant rats a protein-restricted diet persistently alters the methylation of specific cytosines in the hepatic PPAR alpha promoter of the offspring. Br J Nutr (2008). 100(2):278–82. doi:10.1017/S0007114507894438

10. Lumey, LH, Martini, LH, Prineas, R, Myerson, M, and Stein, AD Coronary artery disease in middle-age after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine of 1944-1945. Am J Epidemiol (2011). 173:S97.

11. St Clair, D, Xu, M, Wang, P, Yu, Y, Fang, Y, Zhang, F, et al. Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959-1961. JAMA (2005). 294(5):557–62. doi:10.1001/jama.294.5.557

12. Wang, Z, Li, C, Yang, Z, Zou, Z, and Ma, J Infant exposure to Chinese famine increased the risk of hypertension in adulthood: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Bmc Public Health (2016). 16:435. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3122-x10.1186/s12889-016-3122-x

13. Li, Y, He, Y, Qi, L, Jaddoe, VW, Feskens, EJ, Yang, X, et al. Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes (2010). 59(10):2400–6. doi:10.2337/db10-0385

14. Wang, Z, Zou, Z, Wang, S, Yang, Z, and Ma, J Chinese famine exposure in infancy and metabolic syndrome in adulthood: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Eur J Clin Nutr (2019). 73(5):724–32. doi:10.1038/s41430-018-0211-1

15. Xin, X, Wang, W, Xu, H, Li, Z, and Zhang, D Exposure to Chinese famine in early life and the risk of dyslipidemia in adulthood. Eur J Nutr (2019). 58(1):391–8. doi:10.1007/s00394-017-1603-z

16. Wang, Z, Zou, Z, Yang, Z, Dong, Y, and Ma, J Association between exposure to the Chinese famine during infancy and the risk of self-reported chronic lung diseases in adulthood: a cross-sectional study. Bmj Open (2017). 7(5):e015476. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015476

17. Wang, Z, Zou, Z, Dong, B, Ma, J, and Arnold, L Association between the Great China Famine exposure in early life and risk of arthritis in adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health (2018). 72(9):790–5. doi:10.1136/jech-2017-210334

18. Shen, L, Li, C, Wang, Z, Zhang, R, Shen, Y, Miles, T, et al. Early-life exposure to severe famine is associated with higher methylation level in the IGF2 gene and higher total cholesterol in late adulthood: the Genomic Research of the Chinese Famine (GRECF) study. Clin Epigenetics (2019). 11(1):88. doi:10.1186/s13148-019-0676-3

19. Wang, Z, Song, J, Li, Y, Dong, B, Zou, Z, and Ma, J Early-life exposure to the Chinese famine is associated with higher methylation level in the INSR gene in later adulthood. Sci Rep (2019). 9(1):3354. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-38596-6

20. Roseboom, TJ, van der Meulen, JH, Osmond, C, Barker, DJ, Ravelli, AC, Schroeder-Tanka, JM, et al. Coronary heart disease after prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine, 1944-45. Heart (2000). 84(6):595–8. doi:10.1136/heart.84.6.595

21. Rotar, O, Moguchaia, E, Boyarinova, M, Kolesova, E, Khromova, N, Freylikhman, O, et al. Seventy years after the siege of Leningrad: does early life famine still affect cardiovascular risk and aging?. J Hypertens (2015). 33(9):1772–9. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000640

22. Ekamper, P, van Poppel, F, Stein, AD, Bijwaard, GE, and Lumey, LH Prenatal famine exposure and adult mortality from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other causes through age 63 years. Am J Epidemiol (2015). 181(4):271–9. doi:10.1093/aje/kwu288

23. Shi, Z, Ji, L, Ma, RCW, and Zimmet, P Early life exposure to 1959‐1961 Chinese famine exacerbates association between diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Diabetes (2019). 12:134. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12975

24. Shi, Z, Nicholls, SJ, Taylor, AW, Magliano, DJ, Appleton, S, and Zimmet, P Early life exposure to Chinese famine modifies the association between hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J Hypertens (2018). 36(1):54–60. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000001496

25. Zhang, Y, Ying, Y, Zhou, L, Fu, J, Shen, Y, and Ke, C Exposure to Chinese famine in early life modifies the association between hyperglycaemia and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis (2019). 29(11):1230–6. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2019.07.004

26. Du, R, Zheng, R, Xu, Y, Zhu, Y, Yu, X, Li, M, et al. Early-life famine exposure and risk of cardiovascular diseases in later life: findings from the REACTION study. J Am Heart Assoc (2020). 9(7):e014175. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.014175

27. Zhao, Y, Hu, Y, Smith, JP, Strauss, J, and Yang, G Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol (2014). 43(1):61–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dys203

28. Yang, DL Calamity and reform in China: state, rural society, and institutional change since the Great Leap Famine. Am J Sociol (1998). 102(5):1454–6. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/655956 (Accessed November 15, 2020).

29. Barr, EL, Tonkin, AM, Welborn, TA, and Shaw, JE Validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease events in comparison to medical record adjudication and a statewide hospital morbidity database: the AusDiab study. Intern Med J (2009). 39(1):49–53. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01864.x

30. Dey, AK, Alyass, A, Muir, RT, Black, SE, Swartz, RH, Murray, BJ, et al. Validity of self-report of cardiovascular risk factors in a population at high risk for stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis (2015). 24(12):2860–5. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.08.022

31. Lee, PH, Macfarlane, DJ, Lam, TH, and Stewart, SM Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act (2011). 8:115. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-115

32. Lussana, F, Painter, RC, Ocke, MC, Buller, HR, Bossuyt, PM, and Roseboom, TJ Prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine is associated with a preference for fatty foods and a more atherogenic lipid profile. Am J Clin Nutr (2008). 88(6):1648–52. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26140

33. Clifton, PM, and Keogh, JB A systematic review of the effect of dietary saturated and polyunsaturated fat on heart disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis (2017). 27(12):1060–80. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2017.10.010

34. Aggio, D, Papachristou, E, Papacosta, O, Lennon, LT, Ash, S, Whincup, P, et al. Trajectories of physical activity from midlife to old age and associations with subsequent cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health (2019). 74:130. doi:10.1136/jech-2019-212706

35. Manning, J, and Vehaskari, VM Low birth weight-associated adult hypertension in the rat. Pediatr Nephrol (2001). 16(5):417–22. doi:10.1007/s004670000560

36. Langley-Evans, SC, and Jackson, AA Captopril normalises systolic blood pressure in rats with hypertension induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol (1995). 110(3):223–8. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(94)00177-U

37. Lumey, LH, Martini, LH, Myerson, M, Stein, AD, and Prineas, RJ No relation between coronary artery disease or electrocardiographic markers of disease in middle age and prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine of 1944-5. Heart (2012). 98(22):1653–9. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302419

38. van Abeelen, AF, Elias, SG, Bossuyt, PM, Grobbee, DE, van der Schouw, YT, Roseboom, TJ, et al. Cardiovascular consequences of famine in the young. Eur Heart J (2012). 33(4):538–45. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr228

39. Horenblas, J, de Rooij, SR, and Roseboom, TJ The risk of stroke after prenatal exposure to famine. J Dev Orig Health Dis (2017). 8(6):658–64. doi:10.1017/S2040174417000472

40. Cai, Y, and Feng, W Famine, social disruption, and involuntary fetal loss: evidence from Chinese survey data. Demography (2005). 42(2):301–22. doi:10.1353/dem.2005.0010

Keywords: cardiac epidemiology, fetal medicine, community child health, public health, child nutrition

Citation: Wang Z, Dong Y, Xu R, Wang X, Li Y and Zou Z (2021) Early-Life Exposure to the Chinese Great Famine and Later Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Public Health 66:603859. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.603859

Received: 08 September 2020; Accepted: 22 January 2021;

Published: 09 March 2021.

Edited by:

Licia Iacoviello, Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Neuromed (IRCCS), ItalyCopyright © 2021 Wang, Dong, Xu, Wang, Li and Zou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenghe Wang, d3poMTE2MDg2QHNtdS5lZHUuY24=; Zhiyong Zou, aGFydmV5em91MjAwMkBiam11LmVkdS5jbg==

Zhenghe Wang

Zhenghe Wang Yanhui Dong2

Yanhui Dong2 Xijie Wang

Xijie Wang Yanhui Li

Yanhui Li Zhiyong Zou

Zhiyong Zou