- Department of Health, Behavior, and Society, Institute for Global Tobacco Control, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

Objective: Limited research has examined feminine marketing appeals on cigarette packs in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). We reviewed a systematically collected sample of cigarette packs sold across 14 LMICs in 2013 (Wave 1) and 2015–2017 (Wave 2).

Methods: Packs in Wave 1 (n = 3,240) and Wave 2 (n = 2,336) were coded for feminine imagery and descriptors (flowers, fashion, women/girls, color “pink”). We examined trends in feminine appeals over time, including co-occurrence with other pack features (slim or lipstick shape, flavor, reduced harm, and reduced odor claims).

Results: The proportion of unique feminine cigarette packs significantly decreased from 8.6% (n = 278) in Wave 1 to 5.9% (n = 137) in Wave 2 (p < 0.001). Among all feminine packs, flower-and fashion-related features were most common; a substantial proportion also used flavor and reduced odor appeals.

Conclusion: While there was a notable presence of feminine packs, the decline observed may reflect global trends toward marketing gender-neutral cigarettes to women and a general contempt for using traditional femininity to market products directly to women. Plain packaging standards may reduce the influence of branding on smoking among women.

Introduction

The cigarette pack is an important marketing tool for the tobacco industry and has grown in relevance as companies face increasing advertising restrictions in other mediums [1–4]. Pack shape, color, and design all communicate a brand’s “personality” to attract consumer attention [1, 4]. The use of specific colors, imagery, and text descriptors (e.g. light, mild, smooth) are especially important as they can influence perceptions of product taste and strength [5, 6], as well as the health risks associated with use [6–10]. Tobacco companies intentionally tailor packaging features to appeal to specific consumer subgroups based on demographic and lifestyle factors [11–14]. Importantly, the pack functions as a major advertising platform to draw in and recruit new smokers, including women and girls who rated feminine branded packs, such as the bright pink and black Camel No. 9 pack, as more appealing than non-feminine or non-branded, plain packs [15, 16].

The tobacco industry has long marketed smoking as a socially acceptable activity for women in high-income, Western countries like the United States, Great Britain, and Spain [17–22]. Starting in the 1920s, advertising campaigns in women’s lifestyle magazines promoted cigarettes using themes of independence, fashion, and thinness, (e.g. “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet”) [21–23], and the use of the cigarette as a symbol of glamour, femininity, and women’s emancipation persisted well throughout the late 20th century [22–24]. With respect to packaging, the print advertising campaigns worked in concert with the design of the cigarette and the cigarette pack itself. Tobacco companies extensively researched women’s personal and social preferences related to smoking [4, 20]. The cigarette pack often carried over the Western, stereotypical feminine appeals in the form of imagery, (e.g. flowers, butterflies [22, 25, 26]) and colors, (e.g. pastels, pink [22, 24]) of the advertising campaign, and slim or ultra-thin cigarettes were designed to reinforce the perception of smoking as a feminine, graceful, stylish activity that aligned with the idealized thin and glamourous images of women promoted in magazine ads [20, 22, 25]. Additionally, both packaging and advertisements offered different technologies that met and fortified the odor and taste preferences of women: reduced odor side-stream smoke, a light or mild cigarette that was smoother to smoke and appeared as a “healthier option,” and improved flavor through the use of menthol, mint and other flavor constituents [4, 20].

Collectively, these marketing strategies were effective at increasing cigarette sales and smoking rates among women [27]. Although women still smoke at a lower rate compared to men in nearly all countries [28], women and girls remain a potential market for long-term growth among the major transnational tobacco companies [26, 29–31]. This is particularly relevant in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) where shifting norms around the acceptability of women smoking and increased spending power among women may facilitate smoking uptake [22, 29, 32, 33]. In 2018, less than 5% of women living in LMICs used combustible tobacco compared to 17.9% of women living in high-income countries [28]. However, in those LMICs with the highest global burden of tobacco use, rates of smoking among women is more variable. For example, while less than 3% of women in Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Thailand smoked in 2018, the smoking rate among women in Mexico (6.5%), the Philippines (7.0%), Brazil (9.5%), Ukraine (9.9%), Russia (15.7%), and Turkey (17.0%) were much higher and some approached smoking rates among women in higher-income countries like the United States (16.7%) [28].

Further, evidence suggests that major transnational tobacco companies are employing similar marketing strategies previously used in high-income countries to target women in LMICs [22, 30, 33]. For example, cigarette advertising campaigns in countries like India and the Philippines frequently featured fashionably dressed women who conformed to Western style and beauty standards which may associate smoking with aspirations of glamour, sophistication, and independence from traditional economic and social roles held by women in LMICs [22, 26, 30, 33–35]. In addition, slim cigarettes, lipstick pack shaped cigarettes, and “light” or “mild” cigarettes have also been introduced into the marketplace of several LMCIs [22, 26, 35, 36]. Slim cigarettes that appear to be designed for women were associated with increased odds of experimental smoking among adolescents in China [35], and experimental studies conducted among young women in Mexico (16–18 years old) and Brazil (16–26 years old) found that participants rated flavored cigarette packs branded with feminine colors, (e.g. light pastels, pink) as more appealing than flavored, non-branded plain packs [36, 37]. However, little is known about the extent to which cigarette packs sold in LMICs feature feminine imagery or appeals outside of pack shape and reduced harm claims. Only a small number of studies have examined marketing features present on cigarette packs sold in LMICs [38–42], and none to date has systematically explored the presence of feminine appeals.

The current study addresses this gap and utilizes a large dataset of cigarette packs collected across 14 LMICs to examine the presence of feminine marketing appeals on packs sold in LMICs. Feminine appeals were initially informed by stereotypical, Western features, (e.g. color, fashion appeals, flowers, butterflies, and imagery of women) in advertising and pack design discussed in the extant literature and then refined based on input from country-specific experts. We document trends in the use of these overt feminine marketing appeals on packs over time and by multinational tobacco company, as well as the co-occurrence of feminine appeals with other marketing features historically used to appeal to women, (e.g. slim pack shape, flavor, “light” cigarettes, reduce odor claims). Given the role of the cigarette pack as a marketing platform to attract women and girls and increase interest in product use [15, 16, 24, 35], results from this study can elucidate the ways in which women in LMICs may be targeted by tobacco companies through cigarette packaging and inform policy strategies to reduce the impact of this marketing tactic.

Methods

This study is part of the larger Tobacco Pack Surveillance System (TPackSS) project to monitor compliance with health warning label requirements on tobacco packages sold in 14 LMICs with the highest number of smokers at the time of initial data collection [43]. The primary aim of the TPackSS project is to purchase a comprehensive collection of unique tobacco packs sold in each TPackSS country and assess whether tobacco health warning requirements are implemented as intended. Data have been published on overall compliance with warning label requirements [44], as well as pack features that may detract from the effectiveness of warning label placement on packages, (e.g. tax stamps covering warnings) [45]. Data have also been used to explore the different marketing appeals, (e.g. English language, sports imagery, organic/natural descriptors, reduced harm terminology) present on tobacco packs across the study countries [38, 39, 41, 42].

TPackSS data collection occurred in two waves. In Wave 1 (2013), data collectors purchased cigarette packs (n = 3,240) from 14 LMICs: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine and Vietnam. In Wave 2 (2015–2017), data collectors purchased cigarette packs (n = 2,336) sold in nine of the original 14 LMICs where health warning label requirements were updated since Wave 1: Indonesia, Russia, Thailand, and Vietnam (packs purchased in 2015); Bangladesh, Brazil, India, and the Philippines (packs purchased in 2016); and China (packs purchased in 2017). Wave 2 data were not collected from Egypt, Mexico, Pakistan, Turkey, and Ukraine. Unlike the other nine countries where health warning label requirements were updated and required a new wave of compliance assessment, the warning label requirements in these five countries remained the same between 2013 and 2016 [46]. Therefore, a new compliance assessment was not required and Wave 2 data were not collected.

Study Sample

In each LMIC, data collection occurred in select low, middle, and high socioeconomic status neighborhoods within three of the country’s 10 most populous cities. In China (five) and Wave 2 India (four), we included more than three cities in the sampling frame based on the recommendation of tobacco control expert advisors knowledgeable about the tobacco market in each country [43]. For each identified city, in-country collaborators created a sampling frame of neighborhoods by socioeconomic strata using a variety of local and national sources, including census and property value data. We then selected four neighborhoods within each socioeconomic stratum that were diverse in terms of geographic locale and residential composition. Data collectors visited a total of 12 neighborhoods in each city or 36 neighborhoods in each LMIC, except China and Wave 2 India where we included 60 and 48 neighborhoods, respectively.

Data collectors followed the same standardized protocol to systematically purchase tobacco packs across waves and within each LMIC. A detailed explanation of data collector training and the TPackSS methodology can be found in Smith et al., 2015 [43]. In brief, TPackSS staff traveled to each country to conduct a 5-day in-person training and were available during the entire data collection period to trouble-shoot issues in the field. Data collection targeted pre-selected vendor types in urban neighborhoods that were popular in each country. Packs were purchased from the most popular vendor types in each country and included tobacco shops, kiosks, supermarkets, convenience stores, stalls, street vendors, and superstores. The first vendor in each country served as the index vendor for all other stores visited in that LMIC: data collectors visited a large tobacco vendor in the first sample city, purchased all unique tobacco packs sold at the first vendor, and took a photo of the front panel of each pack to create an image archive. Field staff then visited up to five vendors in the remaining neighborhoods to identify and purchase new, unique packs not already present in the image archive. The image archive was updated following each round of new pack purchase at a vendor. Packs were considered unique if there was at least one exterior difference in the pack design, (e.g. pack size, brand name presentation, colors, promotional item, cellophane, etc.) from other packs in the image archive. Packs that looked exactly the same but had different warning label were not considered unique.

Coding for General Pack Features

All physical packs were sent to Baltimore, Maryland United States and coded by two independent coders for a variety of marketing features. Detailed codebooks for each wave of data collection are available on the TPackSS website (https://globaltobaccocontrol.org/tpackss/resources). For the current analysis, we coded packs for features previously associated with targeted marketing to women [4, 20, 22]: slim pack shape (width of pack ≤1.3 cm), lipstick pack shapes (tall, slender rectangular pack), and flavored packs based on the presence of text (e.g., mint), imagery, (e.g. mint leaf), or flavor capsules which release a flavored liquid into the filter when pressed. Flavor categories included fruit or citrus, alcoholic/energy drink, menthol/mint, clove kretek, other characterizing flavor, other non-characterizing flavor, and unknown flavor capsule. Other characterizing flavors included coffee/tea-, dessert-, herbal-, incense-, and spice-related flavors. Non-characterizing flavors, on the other hand, included “concept” flavors that did not belong to a traditional characterizing flavor category, (e.g. menthol, fruit, dessert, etc.) but rather connoted a taste, smell, or sensory experience using descriptive terms such as “fresh,” “ice burst,” and “purple.” The unknown flavor capsule category included those packs with capsule technology as indicated by the pack or stick branding but no other text or imagery to indicate flavor type. Additionally, we included claims related to reduced odor and smell or reduced harm (“light/lights”; “mild/low” cigarettes).

To capture the global circulation and ownership of feminine appealing packs, we also categorized whether the pack was illicitly sold in the country of purchase (yes/no) and the tobacco company that manufactured each pack. We identified packs as illicit if the health warning label required by the country where the pack was purchased was not present on the pack. For tobacco company, we used a combination of the manufacturing information printed on the pack itself and information on the company structure to identify the tobacco company. In this analysis, we present results for the major tobacco companies (British American Tobacco, China National Tobacco Company, Imperial Tobacco Company, Japan Tobacco International, Korea Tobacco and Ginseng, Philip Morris International) at the time of data collection. We grouped known subsidiary companies together, (e.g. Philip Morris Thailand LTD., Philip Morris Mexico, or Philip Morris Ukraine) with their parent company to create one group per company.

Feminine Appeals Coding

Packs were also coded for the presence of overt feminine marketing appeals discussed in the existing literature [15, 16, 20–26, 30, 35–37]. Specifically, we coded packs as feminine if they contained imagery or descriptors associated with the following: flowers/butterflies, fashion, (e.g. images of jewelry, the term “stylish,” animal prints), women/girls, (e.g. non-sexualized images of women/girls, terms like “lady” or “girl”), the word “pink” or the color pink, and other potential feminine cues, including imagery or descriptors associated with concepts like hearts, kisses, and romance. Brand names, (e.g. Vogue or Glamour) were excluded from text-based coding to ensure that other feminine features beyond brand name were present on the pack to include it in the sample. We also included all lipstick shaped packs in our initial sample of feminine packs. We did not include all slim shaped packs in the initial dataset because, unlike lipstick shaped packs which are almost exclusively associated with women, slim packs could have a broader appeal across gender [36, 47].

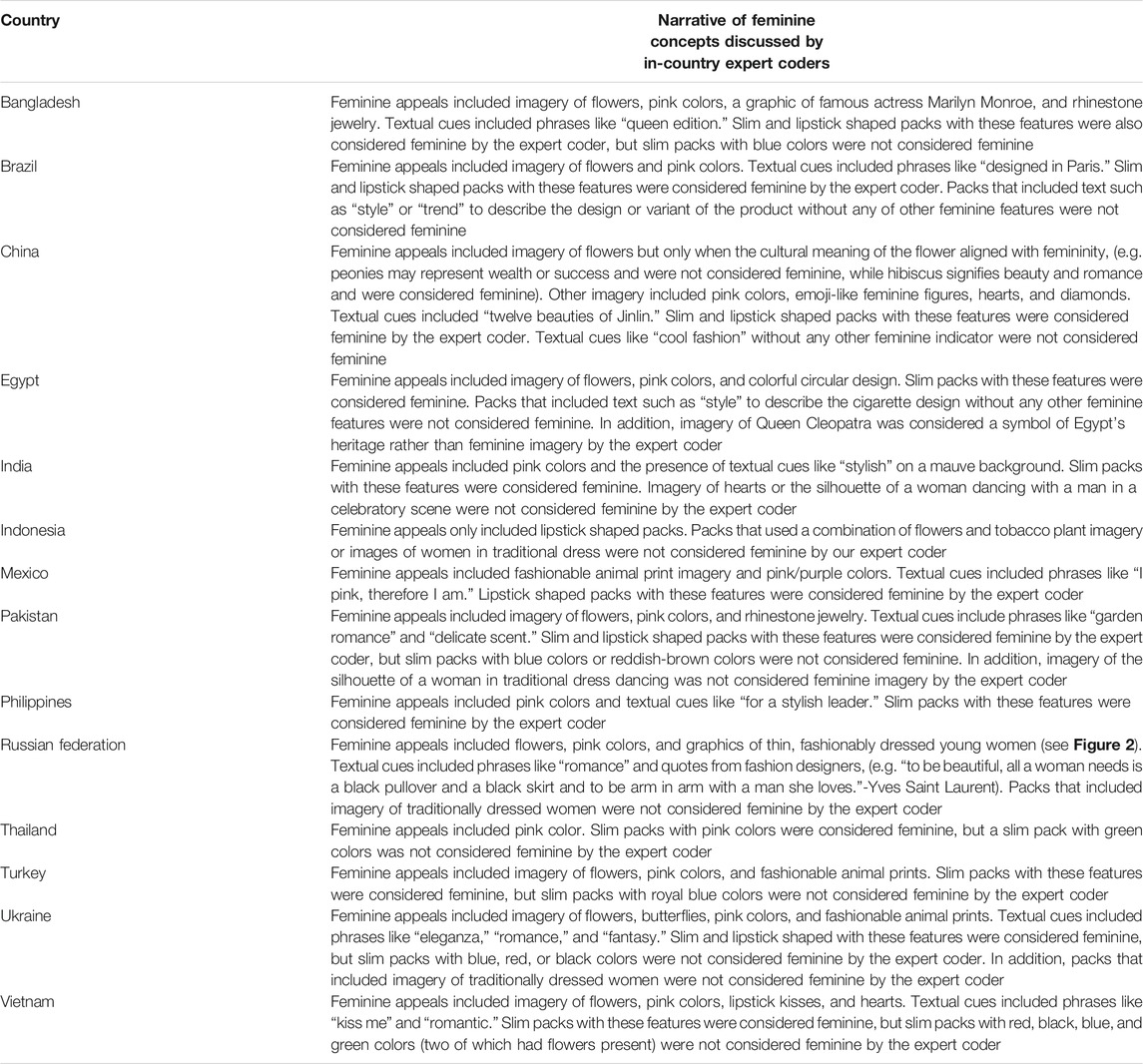

Our coding categories and decisions were heavily informed by stereotypical Western concepts of femininity based on the literature, which may not always communicate femininity in other countries. To ensure that coding was culturally relevant, we identified tobacco control experts from each LMIC and asked them to assess whether packs in our initial sample were feminine based on their knowledge of country-specific norms and feminine symbols. Expert coders also provided a brief rationale for their decision. We next compared the expert coding against the initial coding. In our initial coding, we categorized 656 packs as feminine. In nearly all cases where the expert coder disagreed with the initial coding (n = 241 packs), we accepted the expert coder’s decision and rationale for why the pack was not feminine. In the few cases of disagreement where the expert rationale was unclear or missing (n = 5), we discussed the pack with the expert and arrived at a final coding decision. Our final sample included 415 feminine packs. Table 1 provides a descriptive narrative of the type of feminine appeals included the study sample by country.

TABLE 1. Descriptive narrative of overt feminine appeals identified by expert coders from 14 low- and middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam) included in the Tobacco Pack Surveillance System from 2013 to 2017.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted Fischer’s exact tests of association to examine trends in feminine appeals over time using Stata16 software. We assessed differences by country, major tobacco company, and the presence of other pack features (pack shape, flavor, reduced harm, and reduced odor claims). Tests of association were two sided (p < 0.05).

Results

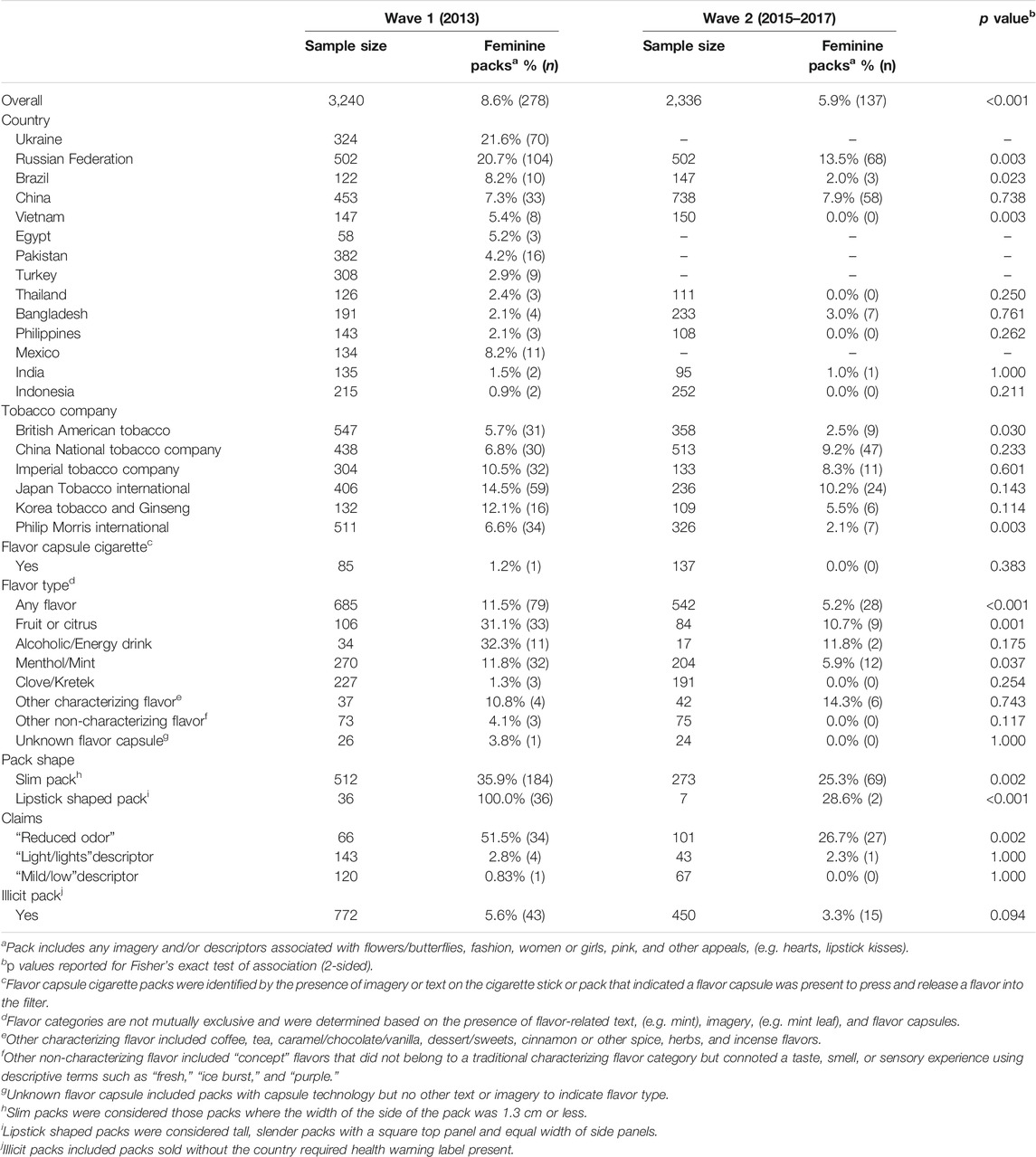

Table 2 presents the proportion of cigarette packs purchased in Wave 1 (2013) and Wave 2 (2015–2017) that contained overt feminine appeals by country, tobacco company, and pack-specific attributes. Overall, the proportion of feminine cigarette packs in the study samples significantly decreased from 8.6% (n = 278 packs) in Wave 1 to 5.9% (n = 137 packs) in Wave 2 (p < 0.001).

TABLE 2. Presence of any overt feminine appeals on cigarette packs (n = 5,575) purchased from 14 low-and middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam) included in the Tobacco Pack Surveillance System in Wave 1 (2013) and Wave 2 (2015–2017) by country and other pack attributes.

By country, Ukraine had the highest proportion of unique feminine cigarette packs (21.6%, n = 70 packs) in Wave 1 followed by Russia (20.7%, n = 104 packs), Brazil (8.2%, n = 10 packs), China (7.3%, n = 33 packs), and Vietnam (5.4%, n = 8 packs). In Wave 2, a significantly smaller proportion of packs from Russia (13.5%, n = 68 packs), Brazil (2.0%, n = 3 packs), and Vietnam (0%, n = 0 packs) contained overt feminine appeals (all p’s < 0.05). The proportion of feminine packs purchased in China remained stable over time (7.9%, n = 58 packs in Wave 2). There was no Wave 2 pack collection in Ukraine.

Most cigarette packs included in this study were brands owned by major multinational tobacco companies. Across waves, over 10% of packs from Japan Tobacco International contained overt feminine appeals (14.5%, n = 59 packs Wave 1; 10.2%, n = 24 packs Wave 2, p = 0.143). In contrast, a smaller proportion of packs from British American Tobacco (5.7%, n = 31 packs) and Phillip Morris International (6.6%, n = 34 packs) contained feminine appeals in Wave 1, and the proportion of overtly feminine packs from both tobacco companies significantly declined in Wave 2 (see Table 2). The most common brands across waves included Vogue from British American Tobacco (n = 24 packs Wave 1, n = 8 packs Wave 2), Glamour from Japan Tobacco International (n = 24 packs Wave 1; n = 14 packs Wave 2), Kiss from Richmond Tobacco Trading Ltd. (n = 27 packs Wave 1, n = 14 packs Wave 2), Style from Imperial Tobacco Company (n = 15 packs Wave 1, n = 9 packs Wave 2), and Nanjing from China National Tobacco Corporation (n = 10 packs Wave 1, n = 11 packs Wave 2).

In Wave 1, a larger proportion of alcoholic/energy drink flavored cigarettes (32.3%, n = 11 packs) followed by fruit flavored cigarettes (31.1%, n = 33 packs) and menthol/mint flavored cigarettes (11.8%, n = 32 packs) contained feminine appeals. In Wave 2, the proportion of fruit (10.7%, n = 9 packs) and menthol/mint flavored packs (5.8%, n = 12 packs) with overt feminine appeals significantly decreased (p = 0.001 and p = 0.037, respectively). With respect to pack shape, nearly 36% of slim packs (n = 184 packs) and all lipstick-shaped packs (100%, n = 36 packs) in Wave 1 contained feminine appeals. In Wave 2, a significantly smaller proportion of slim packs (25.3%, n = 69 packs, p = 0.002) and lipstick-shaped packs (28.6%, n = 2 packs, p < 0.001) contained feminine appeals.

Across waves, very few cigarette packs with flavor capsules or the use of “light/lights” or“mild/low” descriptors contained overt feminine appeals. In Wave 1, around half (51.5%, n = 34 packs) of cigarette packs with “reduced odor” claims contained feminine appeals; however, in Wave 2 the proportion of “reduced odor” packs with feminine appeals significantly declined (26.7%, n = 27 packs, p = 0.002).

The proportion of illicit packs sold in a country that contained overt feminine appeals was small overall and decreased from 5.6% (n = 43 packs) in Wave 1 to 3.3% (n = 15 packs, p = 0.094) in Wave 2.

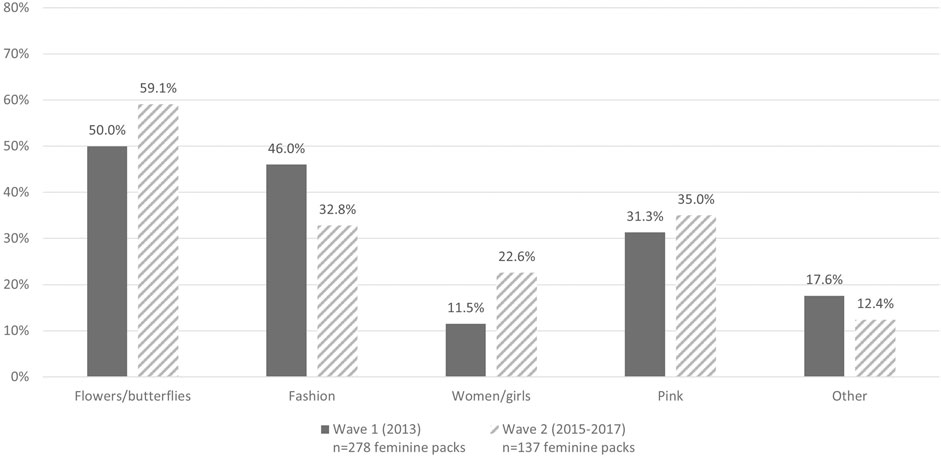

Figure 1 displays the proportion of overtly feminine packs by type of appeal category. Flower-related imagery or descriptors were commonly featured on feminine packs, and at least 50% of feminine packs in Wave 1 and Wave 2 contained flower-based appeals. Fashion-related features were also common and present on 46.0% of feminine packs in Wave 1; however, the presence of fashion appeals significantly decreased in Wave 2 (32.8%, p = 0.011). While imagery and descriptors related to pink were present on approximately one-third of feminine packs in both waves, there was a significant increase in imagery or text associated with women or girls from Wave 1 (11.5%) to Wave 2 (22.6%, p = 0.005). Figure 2 presents examples of stereotypical feminine packs by the four main appeal categories.

FIGURE 1. Image and descriptor-based overt feminine appeals by category among feminine cigarette packs (n = 415) purchased in 14 low-and middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam) included in the Tobacco Pack Surveillance System in Wave 1 (2013) and Wave 2 (2015–2017).

FIGURE 2. Exemplar images of feminine packs purchased across 14 low-and middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Russian Federation, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, Vietnam) included in the Tobacco Pack Surveillance System from 2013 to 2017 by major appeal category: (A) flowers/butterflies (B) fashion (C) women/girls and (D) the color pink.

Discussion

In this study, we found that a notable number of cigarette packs sold in 14 LMICs contained overt feminine imagery or textual cues. This finding aligns with previous reports that women in LMICs are an important growth market for the tobacco industry [22, 29, 32, 33], and reinforces the role of the cigarette pack as a marketing vector to communicate a brand’s intended user [4]. Overall, transnational tobacco companies produced a substantial number of the feminine packs purchased in our study. Although we saw some differences in how femininity was characterized across countries, the feminine packs in this study largely utilized many of the same stereotypical Western marketing features, (e.g. fashion, flowers, pink) and pack features, (e.g. flavor, reduced odor, slim pack shape) that were previously employed to target to women in higher income countries [20, 22, 24]. We also found that the use of terms and imagery associated with women and girls in our sample of feminine packs increased over time, reflecting the potential importance of these marketing features in the context of LMICs. Our findings suggest that the major tobacco companies continue to draw on a consistent playbook to rely on Western standards of femininity to attract the attention and reinforce the sensory and pack shape preferences of women in LMICs [22, 26]. Smaller, domestic tobacco companies like the Richmond Tobacco Trading Ltd. also appeared to utilize the same or similar tactics as the transnational companies to market feminine packs, (e.g. Kiss) in their local market [22]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate efforts across tobacco companies to design packs that signal the suitability of smoking among women in LMICs and potentially increase receptivity to smoking among this demographic group through appealing branded packs [15, 16, 35–37].

One major finding from this study is that the proportion of overtly feminine packs in our systematic sample declined in almost all LMICs over time. Across both study waves, we purchased very few or no feminine packs in countries with low smoking rates among women such as Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and India [28]. At the same time, the proportion of feminine packs in countries with higher rates of smoking among women, like Russia, remained relatively high but also decreased over time [28]. We are limited in our ability to fully monitor this trend given the lack of Wave 2 data from Ukraine—the country with the highest proportion of feminine packs in Wave 1. However, when Ukraine is excluded from the analysis, we still observed a similar, though not statistically significant, decrease in the proportion of feminine packs from Wave 1 (7.1%) to Wave 2 (5.9%, p = 0.073).

Overall, there were no changes in tobacco control policies regarding product packaging in the study countries between Wave 1 and Wave 2 that could potentially account for this decline [46]. However, one potential explanation for the decline is that fewer overtly feminine brands and brand variants were on the market from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Tobacco companies create brand variants that differ by color, pack design, and brand or product descriptors, (e.g. “Marlboro Red”; “ultra-light”) to target different groups of consumers [48, 49], and they invest heavily in market research to understand the appeal of these different brands and brand variants [14, 20, 50, 51]. It is possible that the industry only focused on their most successful brands and brand variants and stopped producing those with lower market sales or less appeal to women.

Another possible explanation for the observed decline in overtly feminine packs is that tobacco companies have either slowed or stopped efforts to target cigarettes to women using the explicit feminine cues. In some LMICs, it is possible that overtly targeting women with branded packaging is not culturally acceptable and other approaches are needed [22, 30]. For example, in India brands like Platinum, a cigarette that explicitly targeted women and their preference for silver jewelry, was less successful than other cigarette brands that used more subtle, indirect cues to link smoking with a woman’s sophistication and sexual allure in billboard and magazine advertising [34]. Additionally, there has been a global shift toward marketing gender-neutral (“dual-sex” [20]) cigarettes to women in Western, high-income countries [18, 20], and a general reactance against the use of traditional femininity and female independence to market products directly to women [52–55]. It may be that a similar trend toward less explicitly feminine and more gender non-specific branding and technologies (e.g., flavor capsules) that contain features that appeal to men and women equally is also taking place in the LMICs included in this study. Emerging evidence suggests that women in several LMICs are more likely than men to prefer cigarette packs with flavor capsules [56, 57], although both groups find capsule packs appealing [56, 58]. This corresponds to cross-cultural research in 10 countries, which included India, China, Russia, and Brazil, that suggests brands that have equally high levels of masculine and feminine appeals (referred to as gender androgenous) have greater reported brand value vs. brands that are exclusively feminine or exclusively masculine [59]. Given the increase in the number of capsule packs in our sample from Wave 1 (n = 85) to Wave 2 (n = 137), it is possible that tobacco companies are targeting women through novel and more gender androgenous or gender-non-specific capsule packs.

A notable exception to the overall decline in overtly feminine packs observed in this study may be China, where the proportion of feminine packs purchased in this study remained stable and high despite the low rates of smoking among women in China [28]. It may be more culturally appropriate in China to market cigarettes with overt feminine appeals. Further, China was the only study country with a significant change in marketing restrictions on tobacco advertising between Wave 1 and Wave 2, where tobacco advertising in public places, including retail stores, and mass media was banned, effective September 2015 [60]. It is possible that tobacco companies may continue to focus attention on marketing cigarettes to consumers through appealing pack designs given the more recent limitations on promoting cigarettes through other advertising platforms [4]. Continued surveillance to examine changes in how cigarettes are marketed to women in China is warranted, including whether there is a general shift toward more gender non-specific packaging.

Despite some slightly different conceptualizations of femininity across countries (see Table 1), feminine packs were identified in every country included in this study. These findings can be useful for tobacco control efforts, primarily policies to reduce branding/targeting of cigarette packs such as single presentation requirements and plain packaging. A single presentation policy, like the one adopted in Uruguay in 2009, could reduce the number of brand variants on the market to only one, single variant per brand family and limit any proliferation of packs aimed at women [49]. Plain packaging policies like those recently implemented in study countries Thailand (2019) and Turkey (2020) could remove branded packaging altogether and require all brands be sold in packs with the same standard color, font, and layout [61]. Both policy options—alone or in combination [48, 49]—have the potential to reduce the influence of the pack itself as an avenue to increase product appeal among consumers, including women in LMICs [36, 37].

This study is subject to several limitations. First, data were derived from a select number of LMICs where the global burden of tobacco use is the highest and our findings may not generalize to other LMICs, particularly in under-represented regions like Africa. Given the design of the TPackSS study to assess compliance with new health warning label requirements over time, we are also limited in our ability to examine trends in feminine marketing in some countries, like Ukraine, where no change in warning label rules occurred between waves and Wave 2 data were not collected. Second, we only purchased cigarette packs from the most populous cities in each country. It is possible that cigarette packs not collected in this study were available in smaller cities and rural areas of a country, which would affect our estimate of the proportion of unique overtly feminine packs in a sold in a country. Additionally, our data collection is intended to capture the breadth of packs available, therefore, the proportions presented are not weighted to reflect the relative market share or popularity of each brand or brand variant. Future analyses of brand-level sales data could complement our study and offer insight into the patterns of sales of feminine packs over time. Finally, our coding structure for overt feminine appeals may not have captured all images or descriptors stereotypically associated with femininity. Even though we worked with an expert from each country to ensure the cultural relevance of our predetermined coding categories, it is possible that we underreport the prevalence of feminine packs across countries if specific feminine imagery or terms were not accounted for in our codebook or in the expert review.

Conclusion

Prior research highlights the importance of women in LMICs as a potential growth market for the tobacco industry [26, 29–31], and the cigarette pack is one key platform to target women in LMICs, particularly as more countries implement bans on advertising and promotion through other channels [46]. Our study found that both transnational and domestic tobacco companies use stereotypical feminine imagery and text to market cigarette packs to women in LMICs. Although we observed an overall decline in the proportion of overtly feminine packs sold in select LMICs over time, our results indicate that imagery or descriptors related to flowers, the color pink, and women and girls remain relevant features on feminine packs. The decline observed may reflect global trends toward marketing gender non-specific cigarettes to women and a general contempt for using traditional femininity to market products directly to women. Plain and standardized packaging can potentially reduce the influence of branded cigarette packs on increasing product appeal, including among women [15, 16, 36, 37]. Importantly, such policies could potentially limit exposure to pack branding for other groups such as youth or low-income populations [38, 62], that may also be disproportionately targeted by cigarette pack marketing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: LC, KW, JEC, and KCS; methodology: LC, KW, JEC, and KCS; software: LC; validation: LC and KW; formal analysis: LC; writing—original draft preparation: LC; writing—review and editing: KW, JEC, and KCS; visualization: LC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported with funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our country-level subject matter experts who were instrumental in identifying overtly feminine packs: Geni Achnas and Olga Knorre from Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids; Lilia Olefir from Center Life; An Nguyen from Health Bridge; Naseeb Kibria, Graziele Grilo, Qinghua Nian, Sejal Saraf, Hanaa Ahsan, and Bekir Kaplin from the Institute for Global Tobacco Control at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Xia Wan from Peking Union Medical College; Michelle Syonne Reyes-Palmones from the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease; Rassamee Sangthong from the Prince of Songkla University; Fatima El-Awa from the Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean of the World Health Organization; and Belén Sáenz de Miera from the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur. We would also like to thank TPackSS project managers Carmen Washington and Michael Iacobelli, the TPackSS coders, and Hammaad Shah who worked on an early draft of this work.

References

1. Dewe, M, Ogden, J, and Coyle, A. The Cigarette Box as an Advertising Vehicle in the United Kingdom: A Case for plain Packaging. J Health Psychol (2015). 20:954–62. doi:10.1177/1359105313504236

2. Moodie, C, and Hastings, GB. Making the Pack the Hero, Tobacco Industry Response to Marketing Restrictions in the UK: Findings from a Long-Term Audit. Int J Ment Health Addict (2011). 9:24–38. doi:10.1007/s11469-009-9247-8

3. Wakefield, M, and Letcher, T. My Pack Is Cuter Than Your Pack. Tob Control (2002). 11:154–6. doi:10.1136/tc.11.2.154

4. Wakefield, M, Morley, C, Horan, JK, and Cummings, KM. The Cigarette Pack as Image: New Evidence from Tobacco Industry Documents. Tob Control (2002). 11:i73–i80. doi:10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73

5. Lempert, LK, and Glantz, S. Packaging Colour Research by Tobacco Companies: The Pack as a Product Characteristic. Tob Control (2017). 26:307–15. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052656

6. Agaku, IT, Omaduvie, UT, Filippidis, FT, and Vardavas, CI. Cigarette Design and Marketing Features Are Associated with Increased Smoking Susceptibility and Perception of Reduced Harm Among Smokers in 27 EU Countries. Tob Control (2015). 24:e233–e240. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051922

7. Bansal-Travers, M, Hammond, D, Smith, P, and Cummings, KM. The Impact of Cigarette Pack Design, Descriptors, and Warning Labels on Risk Perception in the U.S. Am J Prev Med (2011). 40:674–82. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021

8. Hammond, D, Dockrell, M, Arnott, D, Lee, A, and McNeill, A. Cigarette Pack Design and Perceptions of Risk Among UK Adults and Youth. Eur J Public Health (2009). 19:631–7. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp122

9. Lee, JGL, Averett, PE, Blanchflower, T, and Gregory, KR. Is the Cigarette Pack Just a Wrapper or a Characteristic of the Product Itself? A Qualitative Study of Adult Smokers to Inform U.S. Regulations. J Cancer Pol (2018). 15:45–9. doi:10.1016/j.jcpo.2017.12.003

10. Hammond, D, and Parkinson, C. The Impact of Cigarette Package Design on Perceptions of Risk. J Public Health (2009). 31:345–53. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdp066

11. Hendlin, Y, Anderson, SJ, and Glantz, SA. 'Acceptable Rebellion': Marketing Hipster Aesthetics to Sell Camel Cigarettes in the US. Tob Control (2010). 19:213–22. doi:10.1136/tc.2009.032599

12. McKelvey, K, Baiocchi, M, Lazaro, A, Ramamurthi, D, and Halpern-Felsher, B. A Cigarette Pack by Any Other Color: Youth Perceptions Mostly Align with Tobacco Industry-Ascribed Meanings. Prev Med Rep (2019). 14:100830. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100830

13. Balbach, ED, Gasior, RJ, and Barbeau, EM. R.J. Reynolds' Targeting of African Americans: 1988-2000. Am J Public Health (2003). 93:822–7. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.5.822

14. Anderson, SJ. Marketing of Menthol Cigarettes and Consumer Perceptions: a Review of Tobacco Industry Documents. Tob Control (2011). 20:ii20–ii28. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.041939

15. Doxey, J, and Hammond, D. Deadly in Pink: The Impact of Cigarette Packaging Among Young Women. Tob Control (2011). 20:353–60. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.038315

16. Hammond, D, Doxey, J, Daniel, S, and Bansal-Travers, M. Impact of Female-Oriented Cigarette Packaging in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res (2011). 13:579–88. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr045

17. Amos, A, and Haglund, M. From Social Taboo to “Torch of freedom”: The Marketing of Cigarettes to Women. Tob Control (2000). 9:3–8. doi:10.1136/tc.9.1.3

18. Toll, BA, and Ling, PM. The Virginia Slims Identity Crisis: An inside Look at Tobacco Industry Marketing to Women. Tob Control (2005). 14:172–80. doi:10.1136/tc.2004.008953

19. Shafey, O, Fernández, E, Thun, M, Schiaffino, A, Dolwick, S, and Cokkinides, V. Cigarette Advertising and Female Smoking Prevalence in Spain, 1982-1997. Cancer (2004). 100:1744–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.20147

20. Carpenter, CM, Wayne, GF, and Connolly, GN. Designing Cigarettes for Women: New Findings from the Tobacco Industry Documents. Addiction (2005). 100:837–51. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01072.x

21. Tinkler, P. 'red Tips for Hot Lips': Advertising Cigarettes for Young Women in Britain, 1920-70. Women's Hist Rev (2001). 10:249–72. doi:10.1080/09612020100200289

22. Kaufman, NJ, and Nichter, M. The Marketing of Tobacco to Women: Global Perspectives,. In: JM Samet, and S Yoon, editors. IWomen and the Tobacco Epidemic Challenges for the 21st Century. Canada: The World Health Organization (2001). p. 69–98.

24. Pierce, JP, Messer, K, James, LE, White, MM, Kealey, S, Vallone, DM, et al. Camel No. 9 Cigarette-Marketing Campaign Targeted Young Teenage Girls. Pediatrics (2010). 125:619–26. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0607

25.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. Cigarettes Advertising Themes: Women's Cigarettes [Internet]. California: Stanford University (2021). [updated unknown, cited 27 April 2021]. Available from: http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/subtheme.php?token=fm_mt013.php.

26. Amos, A, Greaves, L, Nichter, M, and Bloch, M. Women and Tobacco: A Call for Including Gender in Tobacco Control Research, Policy and Practice. Tob Control (2012). 21:236–43. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050280

27. Pierce, JP, Lee, L, and Gilpin, EA. Smoking Initiation by Adolescent Girls, 1944 through 1988. JAMA (1994). 271:608–11. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03510320048028

28.World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000-2025, 3rd Edition [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2021). [updated 18 December 2019, cited 3 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-global-report-on-trends-in-prevalence-of-tobacco-use-2000-2025-third-edition.

29. Mackay, JL. The Fight against Tobacco in Developing Countries. Tubercle Lung Dis (1994). 75:8–24. doi:10.1016/0962-8479(94)90097-3

30. Knight, J, and Chapman, S. "Asian yuppies..Are Always Looking for Something New and Different": Creating a Tobacco Culture Among Young Asiansare Always Looking for Something New and Different”: Creating a Tobacco Culture Among Young Asians. Tob Control (2004). 13:ii22–ii29. doi:10.1136/tc.2004.008847

31. Hunt, D, Hefler, M, and Freeman, B. Tobacco Industry Exploiting International Women's Day on Social media. Tob Control (2020). 29:e157–e158. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055183

32. Greaves, L. The Meanings of Smoking to Women and Their Implications for Cessation. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2015). 12:1449–65. doi:10.3390/ijerph120201449

33. Mackay, J, and Amos, A. Women and Tobacco. Respirology (2003). 8:123–30. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00464.x

34. Bansal, R, John, S, and Ling, PM. Cigarette Advertising in Mumbai, India: Targeting Different Socioeconomic Groups, Women, and Youth. Tob Control (2005). 14:201–6. doi:10.1136/tc.2004.010173

35. Ho, MG, Shi, Y, Ma, S, and Novotny, TE. Perceptions of Tobacco Advertising and Marketing that Might lead to Smoking Initiation Among Chinese High School Girls. Tob Control (2007). 16:359–60. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022061

36. Mutti, S, Hammond, D, Reid, JL, White, CM, and Thrasher, JF. Perceptions of Branded and plain Cigarette Packaging Among Mexican Youth. Health Promot Int (2016). 32:650–9. doi:10.1093/heapro/dav117

37. Islam, F, Thrasher, JF, Szklo, A, Figueiredo, VC, Perez, CA, White, CM, et al. Cigarette Flavors, Package Shape, and Cigarette Brand Perceptions: an experiment Among Young Brazilian Women. Rev Panam Salud Publica (2018). 42:e5. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2018.5

38. Kleb, C, Welding, K, Cohen, JE, and Smith, KC. The Use of Sports Imagery and Terminology on Cigarette Packs from Fourteen Countries. Substance Use & Misuse (2018). 53:873–80. doi:10.1080/10826084.2017.1363236

39. Smith, KC, Welding, K, Kleb, C, Washington, C, and Cohen, J. English on Cigarette Packs from Six Non-anglophone Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int J Public Health (2018). 63:1071–9. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1164-9

40. Mir, H, Buchanan, D, Gilmore, A, McKee, M, Yusuf, S, and Chow, CK. Cigarette Pack Labelling in 12 Countries at Different Levels of Economic Development. J Public Health Pol (2011). 32:146–64. doi:10.1057/jphp.2011.3

41. Welding, K, Kennedy, RD, Moran, MB, Cohen, JE, and Smith, KC. Natural, Organic, Additive-free and Pure on Cigarette Packs in 14 Countries. Tob Regul Sci (2019). 5:352–9. doi:10.18001/trs.5.4.5

42. Brown, JL, Smith, KC, Welding, K, and Cohen, JE. Misleading Tobacco Packaging: Moving beyond Bans on "Light" and "Mild". Tob Regul Sci (2020). 6:369–78. doi:10.18001/trs.6.5.6

43. Smith, K, Washington, C, Brown, J, Vadnais, A, Kroart, L, Ferguson, J, et al. The Tobacco Pack Surveillance System: A Protocol for Assessing Health Warning Compliance, Design Features, and Appeals of Tobacco Packs Sold in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JMIR Public Health Surveill (2015). 1:e8. doi:10.2196/publichealth.4616

44. Cohen, JE, Brown, J, Washington, C, Welding, K, Ferguson, J, and Smith, KC. Do cigarette Health Warning Labels Comply with Requirements: a 14-country Study. Prev Med (2016). 93:128–34. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.006

45. Iacobelli, M, Clegg Smith, K, Washington, C, Welding, K, and Cohen, JE. When the Tax Stamp Covers the Health Warning Label: Conflicting 'best Practices' for Tobacco Control Policy. Tob Control (2018). 27:119–20. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053417

46.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Tobacco Control Laws [Internet]. Washington D.C.: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (2021). [updated 2021, cited 3 May 2021]. Available from: www.tobaccocontrollaws.org.

47. Dewhirst, T, Lee, WB, Fong, GT, and Ling, PM. Exporting an Inherently Harmful Product: The Marketing of Virginia Slims Cigarettes in the United States, Japan, and Korea. J Bus Ethics (2015). 139:161–81. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2648-7

48. Hoek, J, Gendall, P, Eckert, C, Kemper, J, and Louviere, J. Effects of Brand Variants on Smokers' Choice Behaviours and Risk Perceptions. Tob Control (2016). 25:160–5. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052094

49. DeAtley, T, Bianco, E, Welding, K, and Cohen, JE. Compliance with Uruguay's Single Presentation Requirement. Tob Control (2018). 27:220–4. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053402

50. O'Keefe, AM, and Pollay, RW. Deadly Targeting of Women in Promoting Cigarettes. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972) (1996). 51:67–9.

51. Grau, SL, and Zotos, YC. Gender Stereotypes in Advertising: a Review of Current Research. Int J Advertising (2016). 35:761–70. doi:10.1080/02650487.2016.1203556

52. Howard, E. Pink Truck Ads: Second-Wave Feminism and Gendered Marketing. J Womens Hist (2010). 22:137–61.

53. Beccaria, F, Rolando, S, Törrönen, J, and Scavarda, A. From Housekeeper to Status-Oriented Consumer and Hyper-Sexual Imagery: Images of Alcohol Targeted to Italian Women from the 1960s to the 2000s. Feminist Media Stud (2018). 18:1012–39. doi:10.1080/14680777.2017.1396235

54. Törrönen, J, and Rolando, S. Women's Changing Responsibilities and Pleasures as Consumers: An Analysis of Alcohol-Related Advertisements in Finnish, Italian, and Swedish Women's Magazines from the 1960s to the 2000s. J Consumer Cult (2016). 17:794–822. doi:10.1177/1469540516631151

55. Paraje, G, Araya, D, and Drope, J. The Association between Flavor Capsule Cigarette Use and Sociodemographic Variables: Evidence from Chile. PLoS One (2019). 14:e0224217. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224217

56. Thrasher, JF, Abad-Vivero, EN, Moodie, C, O'Connor, RJ, Hammond, D, Cummings, KM, et al. Cigarette Brands with Flavour Capsules in the Filter: Trends in Use and Brand Perceptions Among Smokers in the USA, Mexico and Australia, 2012-2014. Tob Control (2016). 25:275–83. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052064

57. Brown, J, Zhu, M, Moran, M, Hoe, C, Frejas, F, and Cohen, JE. 'It Has Candy. You Need to Press on it': Young Adults' Perceptions of Flavoured Cigarettes in the Philippines. Tob Control (2021). 30:293–8. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055524

58. Lieven, T, and Hildebrand, C. The Impact of Brand Gender on Brand Equity. Int Mark Rev (2016). 33:178–95. doi:10.1108/imr-08-2014-0276

59.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Unofficial Translation: Rules on Cigarette Package Labeling in the Jurisdiction of the People's Republic of China (2015 Version) [Internet]. Washington D.C.: Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (2021). [updated 2015, cited 27 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/files/live/China/China%20-%20Rules%20on%20Cigarette%20Packaging%20%282015%29.pdf.

60. Cohen, JE, Zhou, S, Goodchild, M, and Allwright, S. Plain Packaging of Tobacco Products: Lessons for the Next Round of Implementing Countries. Tob Induc Dis (2020). 18:93. doi:10.18332/tid/130378

Keywords: marketing, smoking, women, tobacco control, global health, low-and middle-income countries, tobacco packaging

Citation: Czaplicki L, Welding K, Cohen JE and Smith KC (2021) Feminine Appeals on Cigarette Packs Sold in 14 Countries. Int J Public Health 66:1604027. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604027

Received: 10 February 2021; Accepted: 26 May 2021;

Published: 14 June 2021.

Edited by:

Robert Wellman, University of Massachusetts Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Czaplicki, Welding, Cohen and Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lauren Czaplicki, bGN6YXBsaTFAamh1LmVkdQ==

Lauren Czaplicki*

Lauren Czaplicki*