- Department of Home Science, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Objectives: Community Health Workers (CHWs) are important healthcare professionals and key members of team. The purpose of this research is to identify the roles and responsibilities of CHWs in developed and developing countries who provide healthcare assistance to pregnant and lactating women.

Methods: For this particular study, a comparison was conducted between CHWs role in seven developed countries, seven South Asian developing countries, and India, with special emphasis on improving maternal health status.

Results: CHW programs are essential in communities, institutional health programs, and outreach delivery systems. Without active community involvement, CHWs cannot reach their full potential. Developed countries have frameworks for CHWs, such as the Swasthya Shebika Program, Village Health Worker Cadret, Lady Health Worker Programme, and Accredited Social Health Activist program. CHWs are well-paid in developed nations and work with marginalized groups to spread health messages. However, up to 60% of community health workers in low- and lower-middle-income countries do not receive remuneration.

Conclusion: Health systems must support CHWs in choosing technical interventions and providing necessary training, supervision, and logistical support.

Introduction

“Communities” are groups of people who may or may not live close to one another but who still hold the same beliefs, concerns, or identities as per WHO. These groups may be local, national, or international and may have narrow or broad interests. The term “community health worker” (CHW) refers to social service and/or public health professionals who work effectively with and for the community, promoting healthy lifestyles. They might provide paid or unpaid volunteer work for a nearby business, institution, or hospital. Similarities in race, language, culture, financial background, values, and life experiences exist between CHWs and the community individuals they serve. According to the US Department of Labour, CHWs are those who “help individuals and communities adopt healthy behaviors” and “conduct outreach” in addition to “advocating for people’s individual and community health needs” [1].

Health of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period is referred to as maternal health. Every stage should be healthy in order to help women and children achieve their greatest potential for wellbeing. A shocking 287,000 women died during and after pregnancy and delivery in 2020, despite tremendous progress over the previous two decades [2].

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were completed in 2015, were replaced with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are intended to be accomplished by 2030 [3]. The SDG states that by 2030, the neonatal mortality rate should be as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and the MMR (maternal morality ratio) should be reduced by 70 per 100,000 live births. The provision of primary healthcare is hampered by insufficient government spending, a shortage and unequal distribution of the health workforce, and inadequate multi sectoral training [4]. At this time, WHO started to place a fresh emphasis on primary healthcare (PHC) and driven Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as a means of achieving the SDGs related to health.

The National Health Mission (NHM) [5] has two sub-missions: the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) and the National Urban Health Mission (NUHM). The three main elements of the programme are Communicable and Non-Communicable Diseases, Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child, and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A), and. Everyone will have access to fair, affordable, and high-quality healthcare services that are responsible and considerate of the needs of their patients, in accordance to the NHM. UNICEF works with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), NITI Aayog, and state governments to support planning, budgeting, policy creation, capacity building, monitoring, and demand generation. It supports the abilities of health administrators and supervisors at the district and block levels when planning, implementing, monitoring, and supervising efficient maternal healthcare services with a focus on high-risk pregnant women and those in hard-to-reach, vulnerable, and socially disadvantaged communities. Reaching every mother, providing continuum of care, and providing antenatal care are among the measures by the Indian government that UNICEF is supporting.

UNICEF supports the implementation of the MoHFW’s policy, which stipulates that every delivery should be attended by a qualified healthcare professional at a hospital in order to enhance the health and nutrition of pregnant mothers and provide high-quality maternal health services. To guarantee a healthy pregnancy and rapidly identify high-risk conditions that could harm their health or the health of their growing foetus, all expectant mothers must register for antenatal treatment at the local healthcare institution promptly as they become aware of their pregnancy.

To achieve the global goal of improving maternal health and saving women’s lives, we need to accomplish more to reach those who are most at risk, such as women in rural areas, urban slums, households with fewer resources, adolescent mothers, women from minorities and tribal, Scheduled Caste, and Scheduled Tribe groups.

The significance of study is multiple folded. Firstly, it will enable in exploring the problems faced by health workers and beneficiaries in implementing maternal healthcare schemes or programme generated by government. This also enables in knowing nations perspectives regarding maternal healthcare. Understanding more about the precise role, responsibilities, and contributions of these CHWs in enhancing the health status of the community. This will also be helpful to the larger community, government, policymakers, health planners, national programme, researchers, programme managers, and the public health system of India. Recognizing the promoters and obstacles that arise in meeting the community’s fundamental health needs can also be helpful in future efforts to advance their work and social standing and consequently build a healthy nation.

Methods

The present study “Importance of Community Health Workers for Maternal Health Care Management” is undertaken with the objective to understand nations perspectives regarding maternal healthcare. Also, to review the roles and responsibilities of community health workers and recognize the obstacles arising while reaching community health needs.

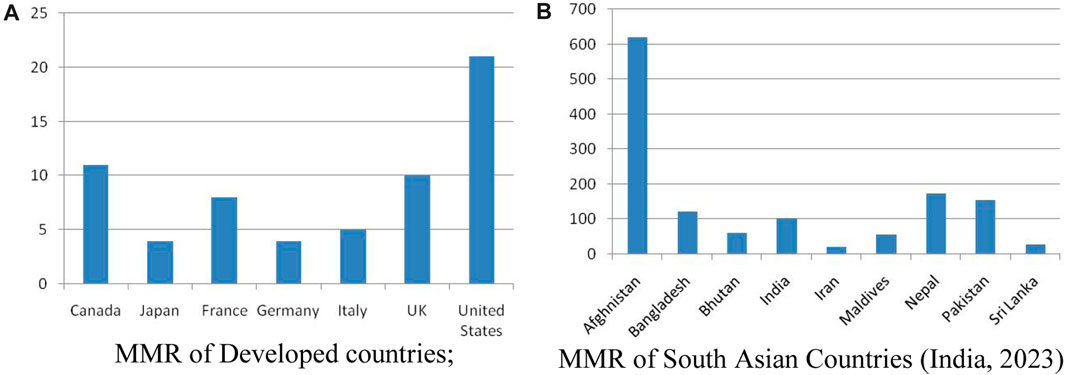

Maternal mortality rate is much higher in developing countries than in developed countries as presented in Figures 1A, B. For this reason, the methodology accepted for the particular study includes CHWs and their roles in seven developed countries and seven south Asian developing countries were compared in addition with Indian studies on contributing roles of community health workers in improving maternal health status.

All nations are divided into three groups based on their economics, according to the World Economic Situation and Prospects (WESP) classifications (2022): established economies, economies in transition, and emerging economies. Seven significant developed nations and South Asian developing nations were chosen for the current study.

Iran being a South Asian developing country was not purposely selected because its MMR is 22 per 100,000 live births. With a maternal mortality rate (MMR) reduction of 75% by 2015, Iran is one of the nations that has succeeded in fulfilling MDG5, having attained the largest reduction among its neighbors, with the exception of Turkey. Iran’s MMR was 274 in 1975, dropped to 150 in 1990, continued to decline, and reached 94 in 1995, 38 in 2005, 30 in 2008, and 25 in 2015, a number comparable to developed countries [6, 7].

A review of the many advancements made by the community health workers (CHWs) in basic healthcare is presented in this paper. This can be used as a valuable resource for learning about the work carried out by CHWs to ensure high-quality healthcare delivered to the target population by reviewing it. This literature review was conducted with the assistance of databases like PubMed, Google, and Google Scholar in order to gather a comprehensive amount of information. As part of this study, we investigated how CHWs are able to efficiently deliver vital healthcare services to the community.

Results

In this section, Figures 1A, B show the maternal mortality ratio (modelled estimate, per 100,000 live births) as reported by WHO [2], UNICEF, UNFPA, the World Bank Group [8], and UNDESA/Population Division.

From the data presented in Figure 1 this is revealed that Iran being an developing country has MMR equivalent to developed countries. The 1920s saw the establishment of a sizable CHW programme in Ding Xian, China. At that time, Jimmy Yen, a Chinese community development specialist with experience teaching adult literacy, and Dr. John B. Grant, a Rockefeller Foundation employee assigned to Peking Medical University, trained illiterate farmers to keep birth and death records, administer smallpox and other disease vaccinations, give first aid and health education talks, and assist communities in keeping their wells clean [9].

The CHW projects in South Asia have a long history of being active, and the CHWs there still play a significant part in primary healthcare and serve as links between the community and the healthcare system. Countries in the region are simultaneously experiencing demographic and epidemiological changes, with populations that are getting older, more urbanized, and suffering from a greater burden of non-communicable diseases. In such a situation, it is vital to increase the contribution of CHW initiatives to PHC strengthening and fulfilling the region’s objectives and aspirations.

Roles and Responsibilities of CHW

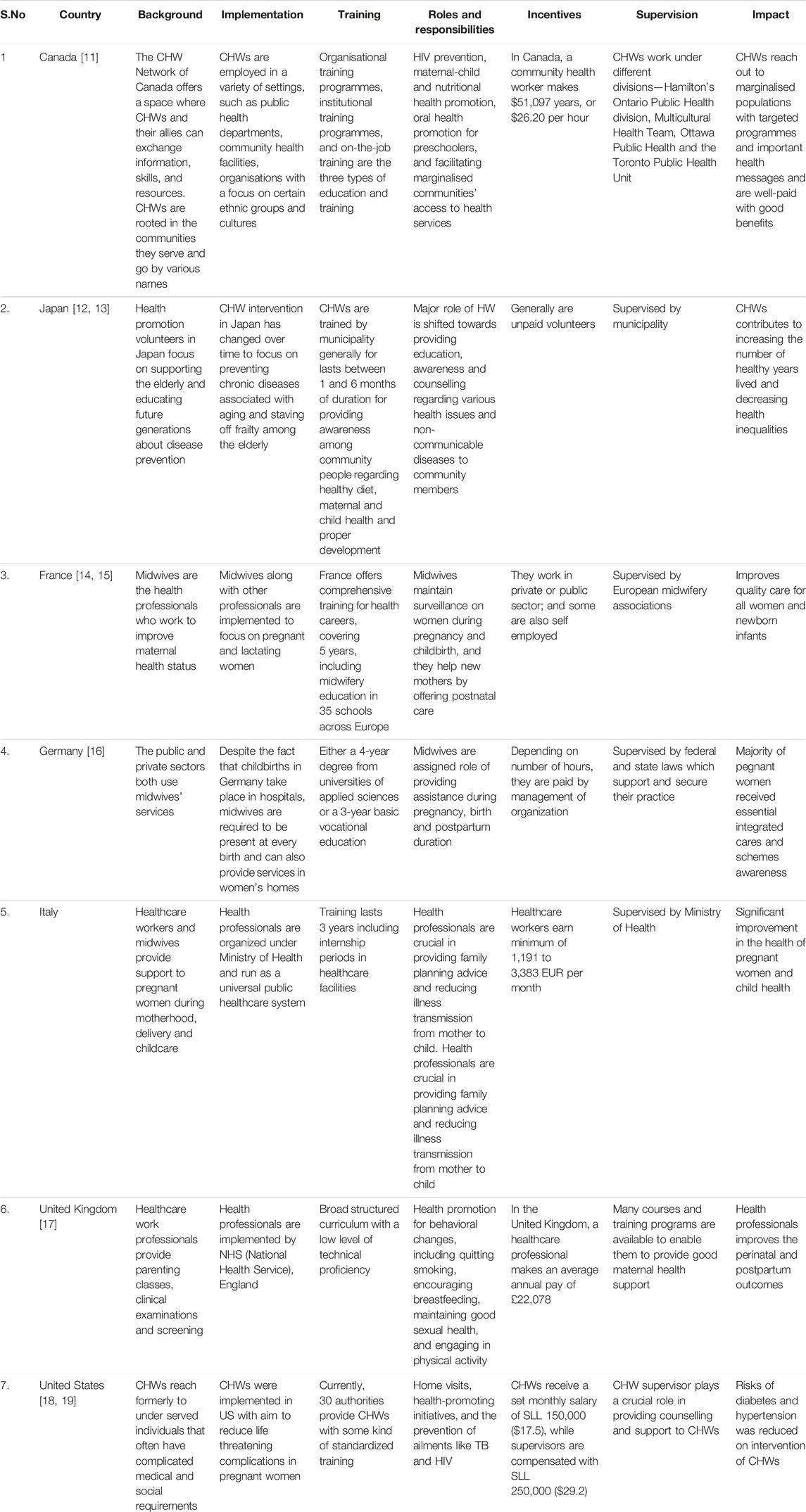

In this section, roles and responsibilities of Community health workers is discussed with special emphasis on their implementation in the community, training, salary and impact on the society. Seven major developed countries - Canada, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, United Kingdom and United States were selected to review the roles and responsibilities of CHWs in developed countries. The roles, responsibilities and implementation of CHWs in respective countries is presented in Table 1.

This can be summed from Table 1, that CHW in developed countries are provided with a framework to discuss their knowledge, challenges, resources and implementations to be applied to create a sustainable growth in terms of maternal health, child care and elderly support. Midwives along with other professionals are implemented to focus on pregnant and lactating women.

CHW are implemented by NHS (National Health Services) with the aim to reduce complications associated with pregnant and lactating women. Health professionals are organized under Ministry of health and run as universal public healthcare system.

In addition to professional education additional training of varied duration 3 months, 6 months or 1 year is provided to increase on job training experience. Various awareness programme are launched to increase knowledge regarding challenges faced by vulnerable group of people (pregnant mothers, lactating women, infants and elderly people). France offers comprehensive training for health careers, covering 5 years, including midwifery education in 35 schools across Europe.

Major role of CHW is shifted towards providing education, awareness and counselling regarding various health issues and non-communicable diseases to community members. HIV prevention, maternal-child and nutritional health promotion, oral health promotion for preschoolers, and facilitating marginalized communities’ access to health services. Despite the fact that childbirths in Germany take place in hospitals, midwives are required to be present at every birth and can also provide services in women’s homes.

CHWs reach out to marginalized populations with targeted programme and important health messages and are well-paid with good benefits. The expense of this care is covered by both statutory and private health insurance providers [10]. CHW are paid by the management of organization depending on the sector whether public or private sector. Additional incentives and benefits are also provided.

Majority of CHWs are supervised by Ministry of Health. Various awareness and training programmes are implemented under the supervision of organizations to enhance the impact of CHW on beneficiaries. CHWs improve health outcomes by reaching marginalized communities, reducing health inequalities, and promoting quality care for women and newborns. They also reduce diabetes and hypertension risks through integrated care and awareness programs.

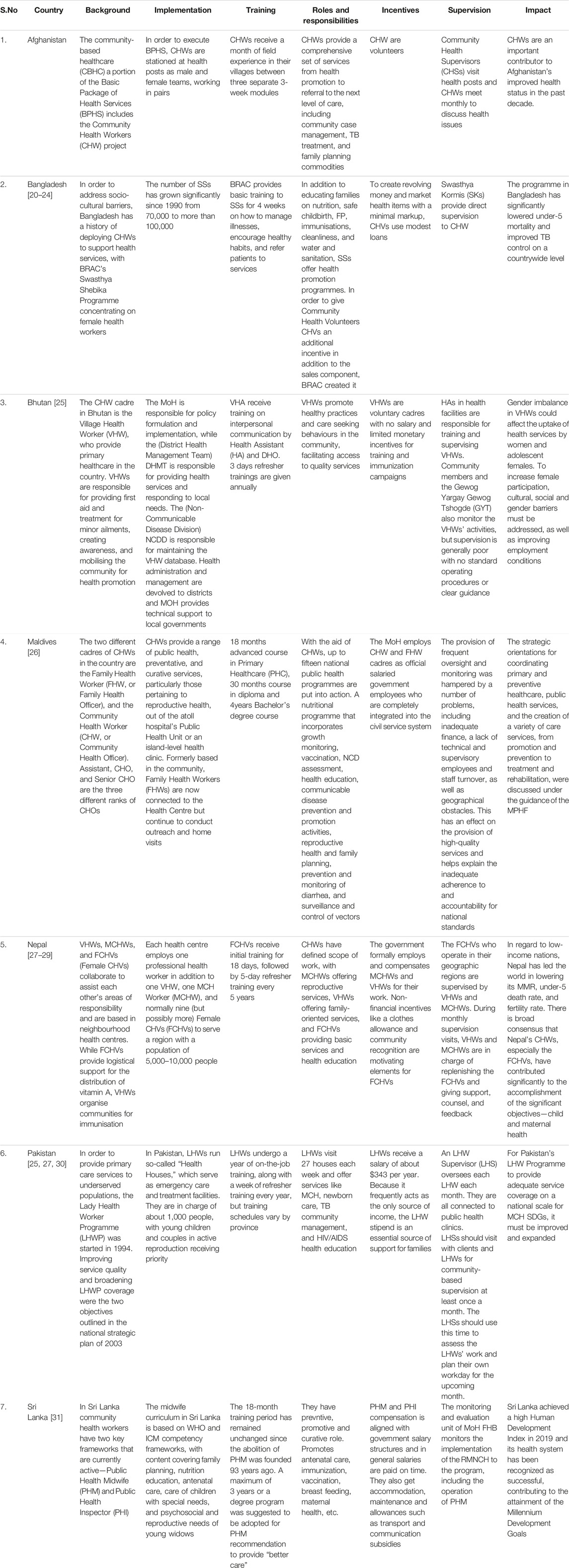

The background information, roles and responsibilities of CHWs in seven Sub Asian developing countries—Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka is presented in Table 2.

CHWs are essential components of the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) community-based healthcare (CBHC) section. Bangladesh has a history of using CHWs to support health services, with BRAC’s Swasthya Shebika (SS) Program focusing on female health workers. Bhutan has a Village Health Worker (VHW) cadre, while Family Health Worker (FHW) and Community Health Worker (CHW) cadres work together. The Lady Health Worker Programme (LHWP) was established in 1994 to provide primary care services to underserved populations. In Sri Lanka, community health workers have two key frameworks: Public Health Midwife (PHM) and Public Health Inspector (PHI).

Health centres, including health centres, employ a District Health Management Team (DHMT) and NGOs to implement BPHS. The MoH is responsible for policy formulation and implementation, while NGOs provide health services and support local needs. Family Health Workers (FHWs) are associated with health centres, providing outreach and house visits. In Pakistan, LHWs provide emergency care at their homes, with priority given to reproductive couples and children under five. Sri Lanka’s midwife curriculum is based on WHO and ICM competency frameworks, covering family planning, nutrition education, antenatal care, and psychosocial and reproductive needs of young widows.

CHWs receive a month of field experience, while SSs receive 4 weeks of basic training, VHA receives interpersonal communication training, and receive 3 days of refresher training annually. FCHVs receive 18 days of initial training, followed by 5-day refresher training every 5 years. LHWs receive 1 year of on-the-job training, including 1 week of refresher training each year. The 18-month training period remains unchanged since PHM abolition 93 years ago.

CHWs offer health promotion, referral, and referral services, including community case management, TB treatment, and family planning. They educate families on nutrition, safe delivery, immunizations, hygiene, and water and sanitation. CHWs implement up to fifteen national public health programs, including nutrition, NCD screening, communicable disease prevention, reproductive health, family planning, and vector surveillance. They provide reproductive services, family-oriented services, and basic health education. LHWs visit 27 households weekly, promoting antenatal care, immunization, vaccination, breastfeeding, and maternal health. A nutrition programme that includes growth monitoring and immunisation, NCD screening and health education, communicable disease prevention and promotion activities, reproductive health and family planning, prevention and surveillance for diarrhoea, and vector surveillance and control is regulated or coordinated by community health workers.

CHW and VHW are voluntary cadres with limited monetary incentives for training and immunization campaigns. The MoH employs CHW and VHW as official government employees, with government compensation and non-financial incentives. LHWs earn $343 a year, with a stipend being crucial for family assistance. Compensation aligns with government salary structures, and they receive accommodation, maintenance, and allowances.

The MoH is responsible for policy formulation and implementation, while the (District Health Management Team) DHMT is responsible for providing health services and responding to local needs. Community Health Supervisors (CHSs) and Swasthya Kormis provide monthly supervision to health posts, while HAs train and supervise VHWs. However, poor supervision and monitoring due to insufficient funding, staff turnover, and geographical barriers hinder quality service provision and compliance with national guidelines. FCHVs are supervised by VHWs and MCHWs, while LHWs are affiliated with public health clinics and oversee them monthly. LHSs review work and create work schedules, while the MoH FHB monitors the implementation of RMNCH and PHM operations. Insufficient funding, shortages and turnover of technical and supervisory staff, and geographical barriers were some of the factors hampering the provision of regular supervision and monitoring [32].

CHWs have significantly contributed to Afghanistan’s improved health status, reducing under-5 mortality and national TB control. Addressing gender imbalance in VHWs and improving employment conditions is crucial for female participation. Nepal has led the world in lowering maternal mortality, under-5 death rate, and fertility rates, while Pakistan needs to expand and strengthen its LHW Program for proper service coverage. Sri Lanka’s health system has achieved high Human Development Index in 2019 and contributed to the attainment of the Millennium Development Goals.

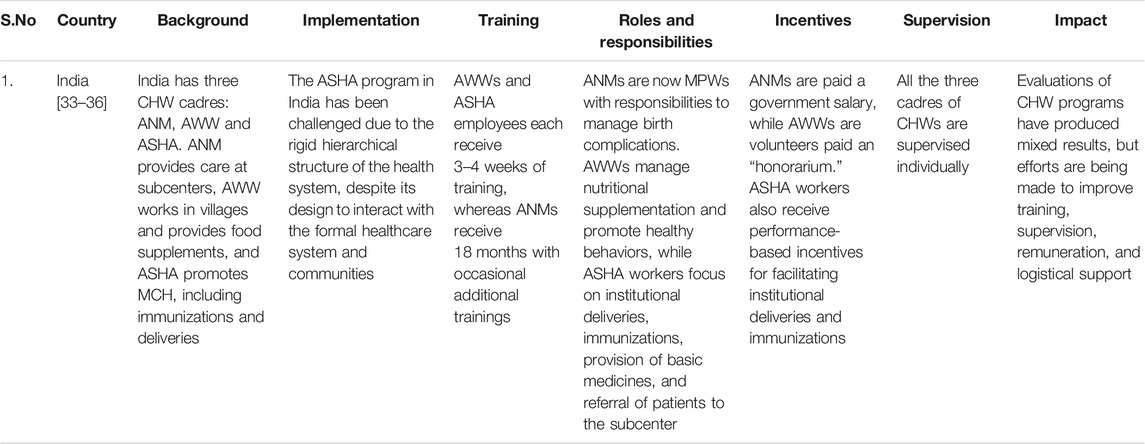

The roles and responsibilities of CHWs in India is presented in Table 3 with special emphasis on Auxiliary Nurse and Midwife (ANM), Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), Anganwadi workers (AWW).

In India the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) was developed in 2000 to improve rural PHC, accountability, and community engagement in the public health sector. In 2005, the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) program was launched with motivating and recognition initiatives. The ASHA Facilitator is responsible for developing health reports and consolidating information about pregnancies, births, deliveries, newborn care, and deaths. By cultivating a sizable pool of CHWs known as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), the Indian National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) 2005 sought to enhance health outcomes.

Family planning, bringing expectant women to hospitals for birth, mother and child health, and health education are among the tasks. They travel with a first aid pack. ASHAs are assigned 200 families, with a total population of roughly 1,000 people, to work in both urban and rural regions.

A 23-day training programme meant to provide ASHA workers with the required knowledge and abilities. ASHAs are honorary volunteers given honorarium and performance-based incentives. States can design their own incentives, with some introducing fixed monthly honorariums. Starting 2018, ASHAs will receive a minimum of Rs. 2,000/- per month for routine activities, along with other task-based incentives approved at Central/State level.

All three workers are supervised individually. THe impact of ANM, ASHA and AWW is positive in nature. They promote better utilization of available schemes by the people. Also help in reducing MMR (Maternal Mortality Rate) and IMR (Infant Mortality Rate).

Discussion

The evidence presented here indicates conclusively that CHW programs are not self-sustaining entities. Instead, they play a significant role in a larger system of activities that includes communities, institutional health programs, and particular interventions that call for an outreach delivery system. Without the active involvement of communities as partners in collaboration and support, CHWs cannot reach their full potential. In order to choose the proper technical interventions for CHW programs and to give them the training, supervision, and logistical support that these interventions need, health systems must fully support them.

According to the 2006 World Health Report, countries that have fewer than 2.28 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 residents typically do not meet targeted 80% coverage for child immunization and competent birth attendance. The proportion of health professionals in the population and the survival of pregnant women and young children are directly correlated. Survival decreases proportionally when the number of health professionals decreases. The improvement of the nation’s condition depends on the protection and promotion of women’s health, that demands for a multisectoral plan of action. In developed countries, health services are provided with free comprehensive coverage to entire population irrespective of socioeconomic status in order to ensure equity in system.

The data show a noticeable rise in the number of health-related human resources, including midwives in Iran [37]. Approximately 33,208 midwives work in the Iranian health system [37] at various levels of management (Ministry of Health and Medical Education at the policy making and management level), education (training midwifery undergraduates, masters, and doctorates, and health workers), and as a member of the healthcare team and under the supervision of obstetricians or general practitioners in health centers [38, 39]. Midwives are the largest group of healthcare providers in health centres in Iran [40].

CHWs in developed countries are provided with a framework to discuss knowledge, challenges, resources, and implementations for sustainable growth in maternal health, child care, and elderly support. They are essential components of the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) community-based healthcare section. Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and India have established frameworks for CHWs, such as the Swasthya Shebika Program, Village Health Worker Cadret, Lady Health Worker Programme, and Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) program.

In developed countries CHW are implemented by National Health Service whereas in developed counties by Ministry of Health. Preventing unintended pregnancy is essential if maternal deaths are to be avoided. All women must have access to legal, safe abortion services as well as high-quality post-abortion care. As long as complications are managed or prevented, the majority of maternal deaths can be avoided. All women must have access to high-quality care during pregnancy, labor, and the postpartum period. The possibility that poor women in rural areas will receive adequate healthcare is the lowest [41]. According to the most recent data, 99% of newborns in high- and upper-middle-income nations benefit from the presence of a qualified midwife, doctor, or nurse. But just 68% of low-income countries and 78% of lower-middle-income countries receive such skilled assistance [42].

ASHA workers receive basic training, refresher training, and field experience in developing countries. They receive a 23-day program to provide knowledge and abilities. Community health workers, answerable to communities, represent the essential “missing link” between societal yearnings and communities in need. They receive interpersonal communication training, refresher training, and on-the-job training, with the 18-month training period unchanged since PHM abolition 93 years ago.

In developed nations, CHWs are well-paid with excellent benefits and work with marginalised groups to spread important health messages and specific programmes. Both public and commercial health insurance companies pay the cost of this care. Depending on the sector—public or private—CHW are paid by the administration of the organisation. There are also additional rewards and incentives offered. However, alternative estimates—those looking at all community health workers rather than just those performing services on behalf of the government—show that in developing countries, up to 60% of community health workers in low- and lower-middle-income countries did not receive any remuneration. In India, ASHA workers rely mainly on the incentive they receive by registering pregnant women for JSY (Janani Suraksha Yojana).

The following are some factors that discourage women from seeking or receiving care during pregnancy and childbirth:

• Social determinants, such as income, access to education, race and ethnicity, that put some sub-populations at greater risk;

• harmful gender norms and/or inequalities that lead to discrimination; and health system failures that lead to 1) poor quality of care, including disrespect, mistreatment, and abuse, 2) insufficient numbers of adequately trained health workers, 3) shortages of essential medical supplies, 4) the poor accountability of health systems.

Barriers to accessing high-quality maternal health treatments must be identified and removed at the health system and social levels in order to promote mother health in developing economy countries so as to achieve sustainable development goals.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. US Dep. Labor Bur. Labor Stat. Standard Occupational Classification: 21–1094 Community Health Worker (2013). Available at: http://www.bls.gov/soc/2010/soc21 (Accessed October 22, 2021).

2. WHO. Selected National Health Accounts Indicators: Measured Levels of Expenditure on Health 2003-2007 (2007). Available at: http://www.who.int/nha/country/nha_ratios_and_percapita_levels_2003-2007.pdf (Accessed March 1, 2023).

3. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (2016). Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals.

4. Chotchoungchatchai, S, Marshall, AI, Witthayapipopsakul, W, Panichkriangkrai, W, Patcharanarumol, W, and Tangcharoensathien, V. Primary Health Care and Sustainable Development Goals. Bull World Health Organ (2020) 98(11):792–800. doi:10.2471/BLT.19.245613

5. Health & Family Welfare-Government of India. Home:: National Health Mission. Home: National Health Mission (2012). Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/ (Accessed June 21, 2023).

6. Moazzeni, MS. Maternal Mortality in the Islamic Republic of Iran: On Track and in Transition. Matern child Health J (2013) 17:577–80. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1043-6

7. World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2010. Nepal: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank Estimates (2012). Avaiable at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/9789241503631/en/ (Accessed September 22, 2023).

8. World Bank Open. Data (2023). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org (Accessed January 31, 2023).

9. Rifkin, S. Community Health Workers. In: W Kirch, editor. Encyclopedia of Public Health. Berlin: Springer Reference (2008). p. 773–81.

10. SGBV. (Das Fünfte Buch Sozialgesetzbuch) (Social law) – Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung (Artikel 1 des Gesetzes vom 20. Dezember 1988, BGBl. I S. 2477, 2482), das durch Artikel 6 des Gesetzes vom 23. Dezember 2016 (BGBl. I S. 3234) geändert worden ist. Dritter Abschnitt §§ 24 a-i (2017). Available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_5/index.html (Accessed April 11, 2023).

11. Rahmati, A. About Us - Community Health Workers (CHW) Network of Canada About Us - Community Health Workers (CHW) Network of Canada (2018). Available at: https://www.chwnetwork.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=27&Itemid=108 (Accessed October 28, 2023).

12. Ministry of Health Labor, and Welfare. Second Healthy Japan 21: Guidelines for the Expansion of Health Promotion (2012). Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/dl/kenkounippon21_01.pdf(Japanese.

13. Taguchi, A, Murayama, H, Takeda, K, Ito, K, and Tonai, S. Recruiting, Training, and Supporting Community Based Health Promotion Volunteers in Japan: Findings From a National Survey. In: 146rd American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Exposition. Sun Diego (2018).

15. MIDWIVES IN FRANCE AND ACROSS THE WORLD. Improving the Health of Women and Newborns (2012). Available at: https://www.ordre-sages-femmes.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Livret-`Congres-ICM-SF_anglais.pdf.

16. Luyben, A, Wijnen, HAA, Oblasser, C, Perrenoud, P, and Gross, MM. The Current State of Midwifery and Development of Midwifery Research in Four European Countries. Midwifery (2012) 29:417–24. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2012.10.008

17. Olaniran, A, Madaj, B, Bar-Zev, S, and van den Broek, N. The Roles of Community Health Workers Who Provide Maternal and Newborn Health Services: Case Studies From Africa and Asia. BMJ Glob Health (2018) 4(4):e001388. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001388

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addressing Chronic Disease Through Community Health Workers, Second Edition (2015). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/docs/chw_brief.pdf.

19. Phalen, J, and Paradis, R. How Community Health Workers Can Reinvent Health Care Delivery in the US. Health Aff Forefront (2015). Rural Health Information Hub. (2020). California. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/states/california (Accessed August 5, 2023). doi:10.1377/forefront.20150116.043851

20. Chowdhury, AM, Chowdhury, S, Islam, MN, Islam, A, and Vaughan, JP. Control of Tuberculosis by Community Health Workers in Bangladesh. Lancet (1997) 350(9072):169–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11311-8

21. Hadi, A. Management of Acute Respiratory Infections by Community Health Volunteers: Experience of Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). Bull World Health Organ (2003) 81(3):183–9. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862003000300008

22. Mahmood, SS, Iqbal, M, Hanifi, SM, Wahed, T, and Bhuiya, A. Are 'Village Doctors' in Bangladesh a Curse or a Blessing? BMC Int Health Hum Rights (2010) 10:18. doi:10.1186/1472-698X-10-18

23. Perry, H. Health for All in Bangladesh: Lessons in Primary Health Care for the Twenty- First Century. Dhaka, Bangladesh: University Press Ltd (2000).

24. Standing, H, and Chowdhury, AM. Producing Effective Knowledge Agents in a Pluralistic Environment: What Future for Community Health Workers? Soc Sci Med (2008) 66(10):2096–107. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.046

25. Hafeez, A, Mohamud, BK, Shiekh, MR, Shah, SA, and Jooma, R. Lady Health Workers Programme in Pakistan: Challenges, Achievements and the Way Forward. J Pak Med Assoc (2011) 61(3):210–5.

26. Balakrishnan, SS, and Caffrey, M. Policy Brief for Maldives. UNICEF (2022). Avaliable at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/18171/file/Maldives%20Country%20Profile.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2023).

27. CHW Technical Task Force. One Million Community Health Workers: Technical Task Force Report. New York, NY: The Earth Institute (2011). Available at: http://www.millenniumvillages.org/uploads/ReportPaper/1mCHW_TechnicalTaskForceReport.pdf (Accessed September 10, 2022).

28. Global Health Workforce Alliance. CCF Case Studies: Nepal: Strengthening Interrelationship Between Stakeholders. USAID (2010). Available at: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/CCF_CaseStudy_Nepal.pdf.

29. Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal. Nepal Health Sector Programme - Implementation Plan II (NHSP -IP 2) 2010 – 2015. NHSP (2010).

30. World Health Organization, Global Health Workforce Alliance. Country Case Study: Pakistan's Lady Health Worker Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and Global Health Workforce Alliance (2008).

31. Balakrishnan, SS, and Caffrey, M. Policy Brief for Sri Lanka. UNICEF (2022). Avaliable at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/18186/file/Sri%20Lanka%20Country%20Profile.pdf.

32. Sharma, R, Webster, P, and Bhattacharyya, S. Factors Affecting the Performance of Community Health Workers in India: A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective. Glob Health Action (2014) 7:25352. doi:10.3402/gha.v7.25352

33. NSSO. National Sample Survey 60th Round. Delhi, India: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, National Sample Survey Organization NSSO (2006).

34. ASHA Workers. Pressreleaseshare (2022). Avaliable at: https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1606212.

35. Balakrishnan, SS, and Caffrey, M. Policy Brief for Bhutan. UNICEF (2022). Avaliable at: https://www.unicef.org/rosa/media/18166/file/Bhutan%20Country%20Profile.pdf.

36. Maternal health. Maternal Health (2023). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1.

37. Doshmangir, L, Bazyar, M, Majdzadeh, R, and Takian, A. So Near, So Far: Four Decades of Health Policy Reforms in Iran, Achievements and Challenges. Arch Iranian Med (2019) 22(10):592–605.

38. Javanparast, S, Baum, F, Labonte, R, Sanders, D, Heidari, G, and Rezaie, S. A Policy Review of the Community Health Worker Programme in Iran. J Public Health Pol (2011) 32(2):263–76. doi:10.1057/jphp.2011.7

39. Ronaghy, HA, Mehrabanpour, J, Zeighami, B, Zeighami, E, Mansouri, S, Ayatolahi, M, et al. The Middle Level Auxiliary Health Worker School: The Behdar Project. J Trop Pediatr (1983) 29(5):260–4. doi:10.1093/tropej/29.5.260

40. Bahadoran, P, Alizadeh, S, and Valiani, M. Exploring the Role of Midwives in Health Care System in Iran and the World. IJNMR/Summer 2 (2009) 14:117–22.

41. Samuel, O, Zewotir, T, and North, D. Decomposing the Urban–Rural Inequalities in the Utilisation of Maternal Health Care Services: Evidence From 27 Selected Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health (2021) 18:216. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01268-8

42. World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund. WHO/UNICEF Joint Database on SDG 3.1.2 Skilled Attendance at Birth (2023). Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/database/.

Keywords: Anganwadi workers, ASHA workers, community health workers, lactating mothers, pregnant women

Citation: Gupta A and Khan S (2024) Importance of Community Health Workers for Maternal Health Care Management. Public Health Rev 45:1606803. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2024.1606803

Received: 03 November 2023; Accepted: 07 February 2024;

Published: 22 February 2024.

Edited by:

Katarzyna Czabanowska, Maastricht University, NetherlandsCopyright © 2024 Gupta and Khan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Archana Gupta, Z2FyY2hhbmE0OTVAZ21haWwuY29t

This Review is part of the PHR Special Issue “Transformative Public Health Education”

Archana Gupta

Archana Gupta Saba Khan

Saba Khan