- 1Tulane Center for Aging and Department of Medicine, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, United States

- 2Tulane School of Social Work, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, United States

Objectives: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been linked with cardiovascular disease (CVD), suggesting a risk for negative health outcomes among individuals with PTSD. This review synthesizes the temporal relationship between PTSD and CVD and highlights the intersection of sex and race.

Methods: Covidence was used to systematically review the literature published between 1980 and 2020.

Results: 176 studies were extracted. 68 (38.64%) of the studies were a predominantly male sample. 31 studies (17.61%) were a predominantly female sample. Most reported participants of both sexes (n = 72; 40.91%) and only 5 (2.84%) did not report respondent sex. No studies reported transgender participants. 110 (62.5%) studies reported racial and ethnic diversity in their study population, 18 (10.22%) described a completely or predominantly white sample, and 48 (27.27%) did not report race or ethnicity of their study population.

Conclusion: A compelling number of studies did not identify sex differences in the link between PTSD and CVD or failed to report race and ethnicity. Investigating sex, race, ethnicity, and the temporal relationship between PTSD and CVD are promising avenues for future research.

Introduction

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2015 and 2018 suggest that the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adults was 49.2% [1]. CVD is also the leading cause of death among women in the United States [2]. Significant progress has been made in identifying the biological factors that elevate the risk of CVD among women [3–5]. Yet, the literature remains less comprehensive regarding the psychosocial factors that contribute to the sex differences in CVD. In addition to women, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults are more likely to be diagnosed or die from heart disease when compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts [6]. Few studies have specifically focused on the psychosocial risk and protective factors among racially diverse populations.

Approximately 60% of men and 50% of women experience at least one trauma in their lives [7–9]. A review of the literature by Hatch and Dohrenwend [10] found that traumatic and other stressful events are more frequent in racial and ethnic minorities. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized as a pervasive and chronic mental health condition, in which an individual experiences lasting adverse psychological and physiological effects associated with a traumatic event they experienced [11]. Women are twice as likely to meet the criteria for PTSD despite having less exposure to traumatic events [12]. Additionally, Black survivors (8.7%) are also more likely than Whites (7.4%) to receive a diagnosis of PTSD after a traumatic event [9, 13–17]. PTSD has been shown to have a relationship with CVD events [18] and early age heart disease mortality [19]. Additionally, adverse childhood experiences have shown a graded relationship with ischemic heart disease [20]. A meta-analytic review by Edmondson et al [21] found PTSD to be independently associated with the risk for the development of coronary heart disease.

Given the preliminary evidence that PTSD is related to later CVD, and the parallel trends regarding the elevated risk for women and racial and ethnic minorities to experience traumatic events and be diagnosed with PTSD, we hypothesize that PTSD may be more than a risk factor for CVD but an important mediator in explaining the sex and race differences observed in rates of CVD. The current study reviews the state of the literature to identify trends and gaps in understanding the documented relationships between sex, race, PTSD, and cardiovascular disease.

PTSD

The current definition of PTSD outlined in the current Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) requires that a person must experience a psychologically distressing event that produces feelings of intense fear and helplessness (i.e., a trauma) [11]. Notable symptoms of PTSD include hyperarousal, intrusive thoughts and memories, avoidance of reminders and activities associated with the trauma, and sensations of re-experiencing the traumatic event (e.g., via flashbacks and nightmares) [11]. The DSM-V added a fourth criterion to previous versions requiring that a survivor also experience negative cognitions or mood changes [11, 22–25].

Besides sex and race, several other psychosocial factors influence the development of PTSD: trauma type [26], socioeconomic status [1], limited social support [27], relationship of the perpetrator [28], limited coping strategies [29], perceiving the impact of the event to be severe [30], and biological and psychological comorbidies [31]. There are sex differences regarding the trauma type that individuals with PTSD experienced. Specifically, one study reported that men identified combat exposure (57.7%) whereas women disclosed rape (74.4%) and sexual molestation (61.4%) as the traumatic events they lived through prior to being diagnosed with PTSD [9].

Determinants that were related to the development of PTSD include resilience [32, 33], morale [34], physical activity [35], and low attachment dependency and anxiety as measured by the Adult Attachment Scale [36]. Beyond an elevated CVD risk, the higher rates of PTSD among women and BIPOC groups are concerning because PTSD is also a risk factor for the development of other psychological issues, like mood, anxiety, and personality disorders [37, 38] and substance misuse disorders [37, 39].

Broadly, PTSD is associated with overall poor health [40–42]. A meta-analysis by Pacella et al [43] found PTSD to be associated with a high frequency of pain, gastrointestinal complaints, and a greater number of medical complaints overall. Additional studies have found significant associations between PTSD, chronic pain [44], somatization of symptoms [45, 46], hospitalizations [47], type 2 diabetes [39] and metabolic syndrome (MetS) [48]. This suggests that PTSD may be an important early warning sign for the development of chronic and costly health conditions.

Cardiovascular Health

CVD is an umbrella term used to refer to several conditions that affect the cardiovascular system (e.g., strokes, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, heart murmurs, and coronary artery disease). Several established factors that predict CVD have been linked with a PTSD diagnosis, including high blood pressure and heart rate [49], non-adherence to medications [50], alcohol and nicotine use, use [51, 52], poor sleep quality [53], anger or hostility [54], and lack of physical activity [36]. Biomarkers like autonomic dysregulation (including parasympathetic limitations), heart rate, blood pressure, endothelial function, baroceptor sensitivity, and lipids have also been studied [55].

The association between psychological distress and physiological illness can be partially explained by the Diathesis Stress Model [56]. The Diathesis Stress Model suggests that humans are born with biological factors that place them at higher risk for the development and onset of various diseases [57]. McKever and Huff [56] applied the diathesis stress model to PTSD and described three pathways that Mutually influence each other in the development of PTSD: a) residual stress or long-term trauma (i.e., the primary mechanism); b) ecological factors (e.g., relationships, support systems, and coping mechanisms); c) and biological factors (e.g., genetics, neurological composition, inherited genes) [56]. Most notable is the relationship between traumatic stress and elevated levels of hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA) activation and cortisol [4]. High cortisol levels have been shown to negatively impact blood pressure, insulin levels, and cholesterol and are therefore influential in healthy heart functioning [58–60].

While components of the relationship between PTSD and CVD have been elucidated in the literature, there is a dearth of research investigating PTSD as a potential mediator of the relationship between sex, race, and CVD. The aims of the current study are threefold: to identify trends in the literature regarding the relationships between sex, race, posttraumatic stress, and CVD; highlight disparities in current knowledge; and suggest recommendations for the next steps in the study of posttraumatic stress and cardiovascular health.

Methods

Study Identification and Selection

Literature searches were conducted using Academic Search Complete (ASC), Medline, APA Psych Info, Embase, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, PTSD Pubs, and PubMed databases. Articles from Medline, APA Psych Info, and Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection were retrieved from the ASC search engine. Keywords associated with concept one, post traumatic stress disorder included “Posttraumatic Stress,” “Post-traumatic Stress,” “post-traumatic stress,” “post traumatic stress,” “PTSD,” and “ptsd.” Keyword searches for concept two, cardiovascular disease, included, “stroke,” “congestive heart failure,” “heart disease,” “cardiac death,” “stress cardiomyopathy,” “cardiac event,” “Cardiovascular Disease,” “CVD,” “Cardiovascular Health,” “Cardio*,” “Myocardial Infarction,” “MI,” “Atrial Fibrillation.” “afib,” “Arrythmia,” “stroke,” “and heart infarction.” Reviewers utilized advanced search options to include “OR” to capture all possible articles including these two concepts limiting findings to articles written in English between 1980 and 2020. Articles included research with humans. The following limiters were further applied within the ASC database via the “Narrow by Subject Thesaurus” function: “post-traumatic stress disorder,” “atherosclerosis,” “blood pressure,” “cerebral ischemia,” “stroke patients,” “ischemia,” “cerebrovascular disease,” and “coronary disease.” Applicable titles and abstracts were uploaded to Covidence, an online systematic review resource that we used to conduct our scoping review.

Study Inclusion Criteria and Evaluation

Only empirical research articles were included in this review. Accordingly, selected articles were a) published between 1980 and 2020, b) peer-reviewed, c) available in English, d) involved human participants, and e) had research questions that pertained to PTSD and cardiovascular outcomes. Inclusion criterion A was determined based upon the year that PTSD was officially included in the DSM [22]. Specifically, we included studies that examined prevalence (especially by race and gender), interventions, and the temporal relationship, including mechanisms and mediators between PTSD and CVD.

Studies were excluded if a) the research question contained the inverse of the temporal relationship of our aim (i.e., posttraumatic stress as secondary to cardiovascular disease); b) full text was not available; c) the document was a literature review, meta-analysis, editorial, commentary, or letter; and d) there was not a legitimate measurement tool for PTSD (e.g., clinician administered PTSD scale [CAPS], PTSD checklist [PCL], Davidson trauma scale, a record of PTSD diagnosis from a psychiatrist [ICD-9 code], etc.) or CVD. Additionally, we excluded studies that investigated cardiometabolic disease and hypertension as outcomes of PTSD instead of mediators between PTSD and CVD.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We adopted a conservative approach to our screening process given that our research question involved a specific direction of a relationship and relied on the usage of validated measurement tools for PTSD and cardiovascular health (both of which are difficult to discern based solely on the abstract). Accordingly, we conducted two waves of screening: an initial title and abstract evaluation to ensure that the basic criteria were met followed by a full-text review to analyze the direction of the relation between PTSD and cardiovascular health and to confirm the utilization of appropriate measurement tools.

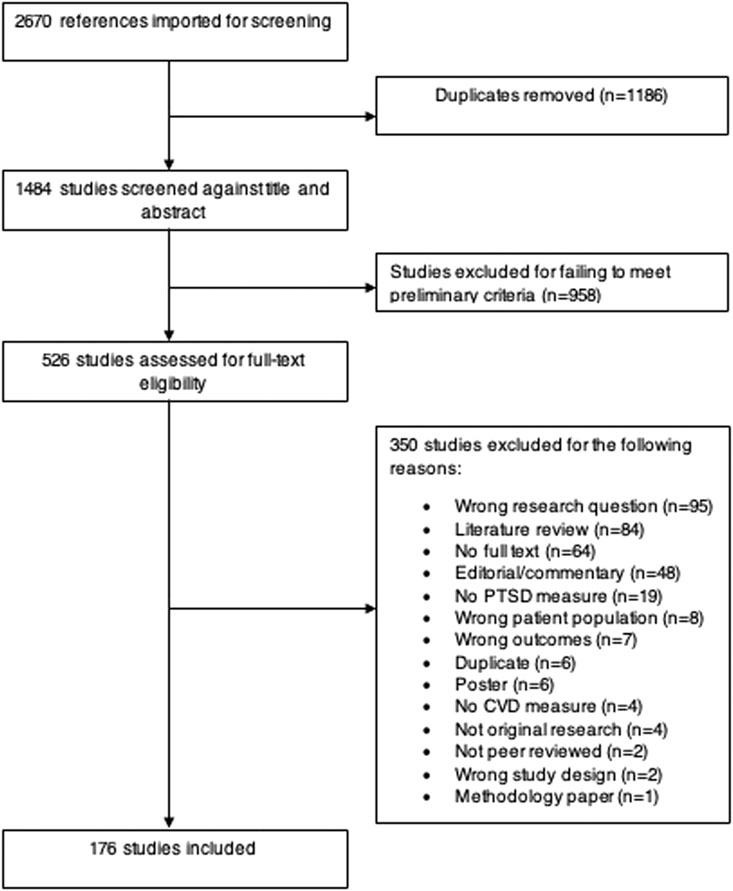

Two reviewers evaluated the retrieved abstracts, applied the inclusion criteria, and voted on “fitness” for the full-text screening. If a discrepancy occurred between votes, a third reviewer was asked to be a “tie-breaker.” A total of 2,670 references were imported to Covidence, an online systematic review resource, and after duplicates were automatically removed (n = 1,186), 1,484 abstracts were screened. 958 abstracts failed to meet preliminary criteria (see above) and 526 studies qualified for full-text review. Covidence tracked our review process via the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework [61].

During the full-text review, 350 studies were further excluded for failing to meet our criteria and a final total of 176 studies were extracted for this scoping review. Cohen’s Kappa for interrater reliability was calculated by Covidence as 0.92 a metric of percent agreement across reviewers. Figure 1 exhibits a flow diagram of our study identification and extraction process.

Results

Study Characteristics

One hundred and seventy-six studies were included in this review. Of these 88 (50%) were published in the biomedical field, 70 (39.77%) in social science, and 18 (10.23%) in public health. We classified studies into four kinds of study design longitudinal (n = 33; 18.75%); cross-sectional (n = 83; 47.16%); intervention (n = 14; 7.95%); and other (n = 46; 26.13%) which included cohort studies, case-control, and prevalence studies. Of these, only 29 (16.48%) identified potential mediators explaining the relationship between PTSD and CVD outcomes. A range of measurement tools was used to assess both PTSD and cardiovascular outputs (reported in Supplementary Table S1).

Sex and Race

We further explored the sex, racial, and ethnic breakdown of the studies included in our sample. Sex data was measured categorically when such information was available. No study supplied any details as to whether the participants had the option to report a sex other than male or female (i.e., a non- binary response). Furthermore, gender and sex language appeared interchangeable or conflated in some cases (e.g., “the male gender” [62]), and gender itself was not directly measured in any of the articles under review. The categorical data on race and ethnicity varied across papers. Some papers only displayed “White” vs. “Non-White” statistics with a majority of studies reporting three or more racial categories.

Sixty-eight (38.64%) of the studies were a complete or predominantly, 85% and above, male sample. Thirty-one studies (17.61%) were a complete, or predominantly, 85% and above, female sample. Overarchingly studies reported participants of both sexes (n = 72; 40.91%) and only five studies (2.84%) did not report respondent sex. Importantly, no studies reported transgender participants. However, it is impossible to conclude that no transgender individuals participated in these studies since gender was not assessed. It may be the case that transgender individuals did participate in this research but their data was simply not captured by the researchers.

Similar patterns were found regarding racial and ethnic diversity among study participants: 101 studies (57.39%) reported racial and ethnic diversity in their study population, 18 studies (10.22%) described a completely or predominantly white (85% and above) sample, and 57 (32.39%) did not report race or ethnicity of the study population.

A total of 72 (40.91%) studies collected data on both sexes and two or more racial or ethnic categories. Of these, 54 (75%) reported including race and/or sex in interaction analyses. 35 studies (19.88%) collected data on both sexes and at least one or no racial category, of which 20 (57.14%) indicated including sex in their interaction analyses. Lastly, 38 papers (21.59%) showed data on at least one or more racial or ethnic groupings and only one or no sex. Of these, 16 studies (42.10%) reported that race or ethnicity was included in interaction analyses.

Discussion

Our review was intended to provide an overview of the state of the literature surrounding the relationship between PTSD and CVD. Our initial search resulted in 1,484 articles suggesting the topic has received a fair amount of attention in the literature. Of these, 958 were excluded largely because they specifically focused on PTSD emerging as a secondary consequence of CVD, illness, and treatment (studies were also excluded for having the wrong population, inadequate measurements, etc.). While this relationship is important, it is qualitatively different from PTSD which precipitates cardiovascular disease. The issue of temporality is an important gap that we identified in the literature. While a few studies (n = 33; 18.75%) in our review firmly establish a temporal order to the relationship between PTSD and CVD, several implied a temporal relationship by examining CVD within a population with PTSD (e.g., veterans). Given the biological and psychosocial capability of a PTSD diagnosis to cause poor health outcomes [41–43, 63] we suggest that this is a key area of exploration that should receive greater attention in the literature using research designs that firmly establish temporal ordering.

While we found greater diversity in study samples than anticipated, only 72 (40.91%) of studies included both sexes, leaving the majority of studies unable to study or identify sex differences regarding PTSD and CVD; both of which are conditions that have demonstrated clear and unique patterns among men and women. Similarly, no studies explored the relationship between PTSD and CVD among transgender participants highlighting the underrepresented nature of transgender and non-binary participants. A more concerning pattern emerged regarding racial and ethnic diversity among study respondents with 32.39% of studies not reporting race and/or ethnicity for study respondents. The lack of racial/ethnic representation in these studies further demonstrates that health disparities begin in research design and that sampling procedures should specifically focus on recruiting racially and ethnically diverse study samples, and that researchers should report demographic characteristics of study participants in their publications.

Only 14 of our final articles (7.95%) were intervention studies. Intervention studies are critical in understanding ways to alleviate not only PTSD symptomology but to improve heart health and decrease risk for CVD among trauma affected populations. Promising therapeutics of note include intranasal oxytocin, respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback, device-guided slow breathing, and variations of exposure therapy. Given the dearth of studies in this arena, future intervention studies should investigate preventative treatment in PTSD patients to reduce risk for CVD as well as expand on retroactive measures. In addition, intervention studies should highlight critical windows of opportunity in which interventions are most effective. Only a small number of studies identified mediation pathways between PTSD and CVD. While there is a plethora of articles that included the word “mediation” in the titles and abstracts, only four studies (2%), to our knowledge, qualified as mediation investigations that were longitudinal and utilized recognized mediation procedures (e.g., Barron and Kenny’s steps for mediation, bootstrapping, etc.). Accordingly, mediation studies may be a promising avenue for those seeking to research the mechanisms between PTSD and CVD.

Limitations

As with all literature reviews, a limitation of this investigation is the finite time frame of our publication inclusion window. Articles in this review were limited to those published between 1980 and September 2020 which naturally leaves out papers published between September 2020 and the time of this publication. We would be remiss if we did not mention at least a few articles that have been published since the time of our study window. These include Korinek et al [64], who investigated the role of PTSD in war stressors and subsequent CVD in older adults, Seligowski et al [65], who examined sex differences in pharmaceuticals in the relationship between PTSD and CVD, and Gavin et al [66], who explored PTSD as a link between racial discrimination and CVD. We recommend readers who are keen on this topic to use this review as a jumping-off point to the ever-growing field of research in PTSD and CVD. Studies were not limited to those conducted in the US but were restricted to those written in English as all authors were only able to assess work in this language. We note that some important work on this topic may be excluded from our analysis due to this limitation. We did include articles from multinational research teams and global populations and note the measurement tools used to assess our outcomes of interest to ensure consistency across regions.

Implications and Future Work

While PTSD and CVD have independently received a significant amount of attention in the literature, there remain gaps in the investigation of the relationship between the two. This review offers a summary of the state of the literature thus far and proposes areas of expansion for the next phase of research. With the emergence of more advanced technology, remote monitoring methods, and awareness regarding the impact of stress on the biological and psychosocial functioning of survivors this line of inquiry has the potential to highlight race and sex-specific trajectories, identify critical windows of opportunity for early intervention, highlight important mediators that should be the focus of interventions to ameliorate deleterious symptomology, and ultimately prevent disease onset.

Author Contributions

All three authors contributed to the conceptualization of the manuscript. LH and TB completed the literature search and coding. All three authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript

Funding

LS’s work was partially supported by Award Number K12HD043451 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/phrs.2023.1605302/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Virani, SS, Alonso, A, Aparicio, HJ, Benjamin, EJ, Bittencourt, MS, Callaway, CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation (2021) 143:e254–e743. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Disease Facts (2020). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm (Accessed June 12, 2022).

3. Kubzansky, LD, Koenen, KC, Jones, C, and Eaton, WW. A Prospective Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Coronary Heart Disease in Women. Health Psychol (2009) 28:125–30. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.28.1.125

4. Michopoulos, V, Vester, A, and Neigh, G. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Metabolic Disorder in Disguise? Exp Neurol (2016) 284:220–9. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.05.038

5. Bangasser, DA, and Valentino, RJ. Sex Differences in Stress-Related Psychiatric Disorders: Neurobiological Perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol (2014) 35:303–19. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.03.008

6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health—United States Infographics (2019). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/spotlight/2019-heart-disease-disparities.htm (Accessed June 12, 2022).

7.Department of Veteran Affairs. How Common Is PTSD in Adults? (2019). Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp (Accessed June 12, 2022).

8.Department of Veteran Affairs. PTSD Basics (2021). Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/what/ptsd_basics.asp#:∼:text=Available%20en%20Espa%C3%B1ol,car%20accident%2C%20or%20sexual%20assault (Accessed June 12, 2022).

9. Kessler, RC, Sonnega, A, Bromet, E, Hughes, M, and Nelson, CB. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1995) 52:1048–60. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

10. Hatch, SL, and Dohrenwend, BP Distribution of Traumatic and Other Stressful Life Events by Race/ethnicity, Gender, SES and Age: A Review of the Research. Am J Community Psychol (2007) 40:313–32. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9134-z

11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. 5th ed Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

12. Tolin, DF, and Foa, EB. Sex Differences in Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Quantitative Review of 25 Years of Research. Psychol Bull (2006) 132:959–92. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959

13. Kessler, RC, Berglund, P, Demler, O, Jin, R, Merikangas, KR, and Walters, EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-Of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2005) 62:593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

14. Roberts, AL, Gilman, SE, Breslau, J, Breslau, N, and Koenen, KC. Race/ethnic Differences in Exposure to Traumatic Events, Development of post-traumatic Stress Disorder, and Treatment-Seeking for post-traumatic Stress Disorder in the United States. Psychol Med (2011) 41:71–83. doi:10.1017/S0033291710000401

15. Breslau, N, Kessler, RC, Chilcoat, HD, Schultz, LR, Davis, GC, and Andreski, P. Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1998) 55:626–32. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626

16. Gill, JM, Szanton, SL, and Page, GG. Biological Underpinnings of Health Alterations in Women with PTSD: A Sex Disparity. Biol Res Nurs (2005) 7:44–54. doi:10.1177/1099800405276709

17. Breslau, N, Davis, GC, Andreski, P, Peterson, EL, and Schultz, LR. Sex Differences in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1997) 54:1044–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012

18. Edmondson, D, and Cohen, BE. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis (2013) 55:548–56. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.004

19. Boscarino, JA. A Prospective Study of PTSD and Early-Age Heart Disease Mortality Among Vietnam Veterans: Implications for Surveillance and Prevention. Psychosom Med (2008) 70:668–76. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817bccaf

20. Felitti, VJ, Anda, RF, Nordenberg, D, Williamson, DF, Spitz, AM, Edwards, V, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med (1998) 14:245–58. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

21. Edmondson, D, Kronish, IM, Shaffer, JA, Falzon, L, and Burg, MM. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Risk for Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analytic Review. Am Heart J (2013) 166:806–14. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.031

22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing (1980).

23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. 3rd ed. rev. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing (1987).

24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing (1994).

25.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing (2000). text rev.

26. Guina, J, Nahhas, RW, Sutton, P, and Farnsworth, SM. The Influence of Trauma Type and Timing on PTSD Symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis (2018) 206:72–6. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000730

27. Harvey, MR. Towards an Ecological Understanding of Resilience in Trauma Survivors. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma (2008) 14:9–32. doi:10.1300/j146v14n01_02

28. Gutner, CA, Rizvi, SL, Monson, CM, and Resick, PA. Changes in Coping Strategies, Relationship to the Perpetrator, and Posttraumatic Distress in Female Crime Victims. J Trauma Stress (2006) 19:813–23. doi:10.1002/jts.20158

29. Pineles, SL, Mostoufi, SM, Ready, CB, Street, AE, Griffin, MG, and Resick, PA. Trauma Reactivity, Avoidant Coping, and PTSD Symptoms: A Moderating Relationship? J Abnorm Psychol (2011) 120:240–6. doi:10.1037/a0022123

30. Gabert-Quillen, CA, Fallon, W, and Delahanty, DL. PTSD after Traumatic Injury: An Investigation of the Impact of Injury Severity and Peritraumatic Moderators. J Health Psychol (2011) 16:678–87. doi:10.1177/1359105310386823

31. Evans, A, and Coccoma, P. Trauma-informed Care: How Neuroscience Influences Practice. New York: Routledge (2017).

32. Lee, JS, Ahn, YS, Jeong, KS, Chae, JH, and Choi, KS. Resilience Buffers the Impact of Traumatic Events on the Development of PTSD Symptoms in Firefighters. J Affect Disord (2014) 162:128–33. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.031

33. Quan, L, Zhen, R, Yao, B, Zhou, X, and Yu, D. The Role of Perceived Severity of Disaster, Rumination, and Trait Resilience in the Relationship between Rainstorm-Related Experiences and PTSD Amongst Chinese Adolescents Following Rainstorm Disasters. Arch Psychiatr Nurs (2017) 31:507–15. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2017.06.003

34. Britt, TW, Adler, AB, Bliese, PD, and Moore, D Morale as a Moderator of the Combat Exposure-PTSD Symptom Relationship. J Traum Stress (2013) 26:94–101. doi:10.1002/jts.21775

35. Oppizzi, LM, and Umberger, R The Effect of Physical Activity on PTSD. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2018) 39:179–87. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1391903

36. Scott, S, and Babcock, JC. Attachment as a Moderator between Intimate Partner Violence and PTSD Symptoms. J Fam Violence (2009) 25:1–9. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9264-1

37. Smith, SM, Goldstein, RB, and Grant, BF. The Association between post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Lifetime DSM-5 Psychiatric Disorders Among Veterans: Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). J Psychiatr Res (2016) 82:16–22. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.022

38. Alastalo, H, Räikkönen, K, Pesonen, AK, Osmond, C, Barker, DJP, Kajantie, E, et al. Cardiovascular Health of Finnish War Evacuees 60 Years Later. Ann Med (2009) 41:66–72. doi:10.1080/07853890802301983

39. Jacobsen, LK, Southwick, SM, and Kosten, TR. Substance Use Disorders in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Review of the Literature. Am J Psychiatry (2001) 158:1184–90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1184

40. Dyball, D, Evans, S, Boos, CJ, Stevelink, SAM, and Fear, NT. The Association between PTSD and Cardiovascular Disease and its Risk Factors in Male Veterans of the Iraq/Afghanistan Conflicts: A Systematic Review. Int Rev Psychiatry (2019) 31:34–48. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1580686

41. Barrett, DH, Doebbeling, CC, Schwartz, DA, Voelker, MD, Falter, KH, Woolson, RF, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Self-Reported Physical Health Status Among U.S. Military Personnel Serving during the Gulf War Period: a Population-Based Study. Psychosomatics (2002) 43:195–205. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.195

42. McFarlane, J, Symes, L, Frazier, L, McGlory, G, Henderson-Everhardus, MC, Watson, K, et al. Connecting the Dots of Heart Disease, Poor Mental Health, and Abuse to Understand Gender Disparities and Promote Women’s Health: A Prospective Cohort Analysis. Health Care Women Int (2010) 31:313–26. doi:10.1080/07399330902893853

43. Pacella, ML, Hruska, B, and Delahanty, DL. The Physical Health Consequences of PTSD and PTSD Symptoms: A Meta-Analytic Review. J Anxiety Disord (2013) 27:33–46. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.08.004

44. Beckham, JC, Crawford, AL, Feldman, ME, Kirby, AC, Hertzberg, MA, Davidson, JR, et al. Chronic Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Chronic Pain in Vietnam Combat Veterans. J Psychosom Res (1997) 43:379–89. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00129-3

45. Andreski, P, Chilcoat, H, and Breslau, N. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Somatization Symptoms: A Prospective Study. Psychiatry Res (1998) 79:131–8. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00026-2

46. Avdibegovic, E, Delic, A, Hadzibeganovic, K, and Selimbasic, Z. Somatic Diseases in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Med Arh (2010) 64:154–7.

47. Jordan, HT, Stellman, SD, Morabia, A, Miller-Archie, SA, Alper, H, Laskaris, Z, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Hospitalizations in Relation to Exposure to the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center Disaster and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Am Heart Assoc (2013) 2:e000431. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000431

48. Rosenbaum, S, Stubbs, B, Ward, PB, Steel, Z, Lederman, O, and Vancampfort, D. The Prevalence and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and its Components Among People with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Metabolism (2015) 64:926–33. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2015.04.009

49. Paulus, EJ, Argo, TR, and Egge, JA. The Impact of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate in a Veteran Population. J Trauma Stress (2013) 26:169–72. doi:10.1002/jts.21785

50. Kronish, IM, Lin, JJ, Cohen, BE, Voils, CI, and Edmondson, D. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Medication Nonadherence in Patients with Uncontrolled Hypertension. JAMA Intern Med (2014) 174:468–70. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12881

51. Dennis, PA, Watkins, L, Calhoun, PS, Oddone, A, Sherwood, A, Dennis, MF, et al. Posttraumatic Stress, Heart-Rate Variability, and the Mediating Role of Behavioral Health Risks. Psychosom Med (2014) 76:629–37. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000110

52. Scherrer, JF, Salas, J, Cohen, BE, Schnurr, PP, Schneider, FD, Chard, KM, et al. Comorbid Conditions Explain the Association between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Heart Assoc (2019) 8:e011133. doi:10.1161/jaha.118.011133

53. Krakow, B, Germain, A, Warner, TD, Schrader, R, Koss, M, Hollifield, M, et al. The Relationship of Sleep Quality and Posttraumatic Stress to Potential Sleep Disorders in Sexual Assault Survivors with Nightmares, Insomnia, and PTSD. J Trauma Stress (2001) 14:647–65. doi:10.1023/A:1013029819358

54. Ouimette, P, Cronkite, R, Prins, A, and Moos, RH. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Anger and Hostility, and Physical Health Status. J Nerv Ment Dis (2004) 192:563–6. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000135650.71761.0b

55. Dedert, EA, Calhoun, PS, Watkins, LL, Sherwood, A, and Beckham, JC. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease: A Review of the Evidence. Ann Behav Med (2010) 39:61–78. doi:10.1007/s12160-010-9165-9

56. McKeever, VM, and Huff, ME A Diathesis-Stress Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Ecological, Biological, and Residual Stress Pathways. Rev Gen Psychol (2003) 7:237–50. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.7.3.237

57. Colodro-Conde, L, Couvey-Duchesne, B, Zhu, G, Coventry, WL, Byrne, EM, Gordon, S, et al. A Direct Test of the Diathesis–Stress Model for Depression. Mol Psychiatry (2018) 23:7. doi:10.1038/mp.2017.130

58. Whitworth, JA, Williamson, PM, Mangos, G, and Kelly, JJ. Cardiovascular Consequences of Cortisol Excess. Vasc Health Risk Manag (2005) 1:291–9. doi:10.2147/vhrm.2005.1.4.291

59. Litchfield, WR, Hunt, SC, Jeunemaitre, X, Fisher, ND, Hopkins, PN, Williams, RR, et al. Increased Urinary Free Cortisol: A Potential Intermediate Phenotype of Essential Hypertension. Hypertension (1998) 31:569–74. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.31.2.569

60. Maduka, IC, Neboh, EE, and Ufelle, SA. The Relationship between Serum Cortisol, Adrenaline, Blood Glucose and Lipid Profile of Undergraduate Students under Examination Stress. Afr Health Sci (2015) 15:131–6. doi:10.4314/ahs.v15i1.18

61. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (2021) 371:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

62. Ahmadi, N, Hajsadeghi, F, Mirshkarlo, H, Budoff, M, Yehuda, R, and Ebrahimi, R. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Coronary Atherosclerosis, and Mortality. Am J Cardiol (2011) 108:29–33. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.340

63. Nichter, B, Norman, S, Haller, M, and Pietrzak, RH. Physical Health burden of PTSD, Depression, and Their Comorbidity in the U.S. Veteran Population: Morbidity, Functioning, and Disability. J Psychosom Res (2019) 124:109744. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109744

64. Korinek, K, Young, Y, Teerawichitchainan, B, Kim Chuc, NT, Kovnick, M, and Zimmer, Z. Is War Hard on the Heart? Gender, Wartime Stress and Late Life Cardiovascular Conditions in a Population of Vietnamese Older Adults. Soc Sci Med (2020) 265:113380. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113380

65. Seligowski, AV, Duffy, LA, Merker, JB, Michopoulos, V, Gillespie, CF, Marvar, PJ, et al. The Renin-Angiotensin System in PTSD: A Replication and Extension. Neuropsychopharmacology (2021) 46:750–5. doi:10.1038/s41386-020-00923-1

66. Gavin, A, Woo, B, Conway, A, and Takeuchi, D. The Association between Racial Discrimination, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Cardiovascular-Related Conditions Among Non-hispanic Blacks: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). J Racial Ethn Health Disparities (2022) 9:193–200. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00943-z

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, scoping review, sex, race, posttraumatic stress disorder

Citation: Hunter LD, Boer T and Saltzman LY (2023) The Intersectionality of Sex and Race in the Relationship Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev 44:1605302. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2023.1605302

Received: 06 August 2022; Accepted: 07 June 2023;

Published: 27 June 2023.

Edited by:

Raquel Lucas, University Porto, PortugalCopyright © 2023 Hunter, Boer and Saltzman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Leia Y. Saltzman, bHNhbHR6bWFuQHR1bGFuZS5lZHU=

Lauren D. Hunter1

Lauren D. Hunter1 Leia Y. Saltzman

Leia Y. Saltzman