- Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Objectives: Complex systems thinking methods are increasingly called for and used as analytical lenses in public health research. The use of qualitative system mapping and in particular, causal loop diagrams (CLDs) is described as one promising method or tool. To our knowledge there are no published literature reviews that synthesize public health research regarding how CLDs are created and used.

Methods: We conducted a scoping review to address this gap in the public health literature. Inclusion criteria included: 1) focused on public health research, 2) peer reviewed journal article, 3) described and/or created a CLD, and 4) published in English from January 2018 to March 2021. Twenty-three articles were selected from the search strategy.

Results: CLDs were described as a new tool and were based upon primary and secondary data, researcher driven and group processes, and numerous data analysis methods and frameworks. Intended uses of CLDs ranged from illustrating complexity to informing policy and practice.

Conclusion: From our learnings we propose nine recommendations for building knowledge and skill in creating and using CLDs for future public health research.

Introduction

There is a trend in public health research for the application of complex systems thinking methods and tools [1–3]. We conceptualize public health research from this perspective in terms of examining systems that are complex webs of sectors, institutions, people, structures, and interventions that aspire to maintain and improve population health. Furthermore, we value public health research that is “based on the principles of social justice, attention to human rights and equity, evidence-informed policy and practice, and addressing the underlying determinants of health” [4].

There are published review articles regarding complex systems thinking methods used in public health research and together these paint a broad landscape [2, 3, 5–10]. In this literature, there is clear support for using qualitative system mapping and in particular, causal loop diagrams (CLDs) as analytical tools to embed complex systems thinking. The origins of the use of CLDs emanate from the system dynamics branch of systems science founded by Forrester [11] and CLDs are needed because “we live in a complex of nested feedback loops” [12]. One example of using a CLD in public health research is a study of factors that influenced health promotion policy and practice in a regional public health system [13]. Here, the CLD was useful because “feedback mechanisms can be seen as leverage points to strengthen systems” and to “identify potential opportunities to disrupt or slow down vicious feedback mechanisms or amplify those that are virtuous cycles.” At the time of this study (2018), there were few examples of CLDs in public health literature [14–21].

To our knowledge there are no published reviews that synthesize public health research in terms of how CLDs are created and used. We were motivated to conduct a literature review to determine how CLD methodology could be used to identify leverage points in local public health systems to strengthen the response to COVID-19 in Canada. The aim of this paper is to address this gap in the literature and synthesize knowledge from recent innovations for our research and contribute to knowledge development. We posed two research questions: 1) How are CLDs created and used in recent (>2018) public health research? 2) What recommendations emerge regarding how to create and use CLDs in public health research?

Methods

A scoping review was chosen for this study in order “to examine how research is conducted” and “to provide an overview or map of the evidence” [22]. A narrative synthesis approach was utilized as the topic required exploration more than explanation and human and time resources were limited [23]. Key issues identified by Byrne [24] to strengthen the review were addressed such as ensuring transparency in search strategy and data extraction, analysis and synthesis.

Search Strategy

Literature was searched using the Scopus and PubMed databases and used the following search terms: causal loop diagram*, complex*, system* thinking, method*, tool, approach, research, and public health. Inclusion criteria were 1) public health research, 2) peer reviewed journal article, 3) described or created a CLD as a research method, and 4) published in English from January 2018 to March 2021. The key objective was to find state-of-the-field examples of CLDs, therefore, extensive hand searches of references was completed. It is important to note that piloting this search strategy uncovered numerous articles that only mentioned CLDs and did not explicitly meet the criteria of “described or created a CLD as a research method.” While we set out to use PRISMA guidelines we deemed it unnecessary given the search strategy quickly became one of including all articles that meet our inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Study selection was conducted by one author (LBL) while appraisal and duplicate independent data extraction and validation was conducted by two authors (LBL and CH). CN provided input throughout the study and facilitated discussion about any differences. Data extraction followed these six categories:

1) Research aim,

2) Description of complex systems thinking,

3) Why a CLD was selected as a method,

4) How the CLD was created,

5) How the CLD was used, and

6) Recommendations for future research using CLDs.

Two authors (LBL and CH) extracted verbatim text that aligned with the extraction categories and these were saved to a spreadsheet. Both authors reviewed the spreadsheet in its entirety, discussed individual articles to gain clarity, and wrote summary paragraphs to identify high level themes. Following this, for each article, summary statements were written for the six extraction categories and a table was created. The two authors reviewed each other’s summaries for accuracy and revisions were made. Finally, directed content analysis was used to interpret extracted data “through systematic classification of coding and identifying themes and patterns” [25].

Results

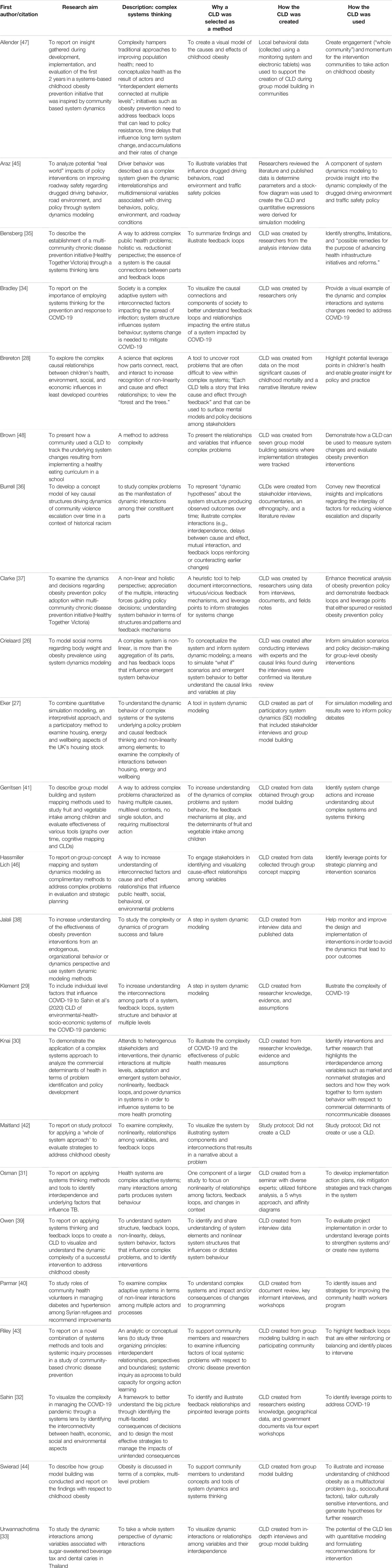

We found 23 articles in total that met our inclusion criteria. A list of these articles and summary statements are provided in Table 1. This section answers our first research question: How are CLDs created and used in recent (>2018) public health research? The organization of this section mirrors the six data extraction categories indicated above.

Research Aims

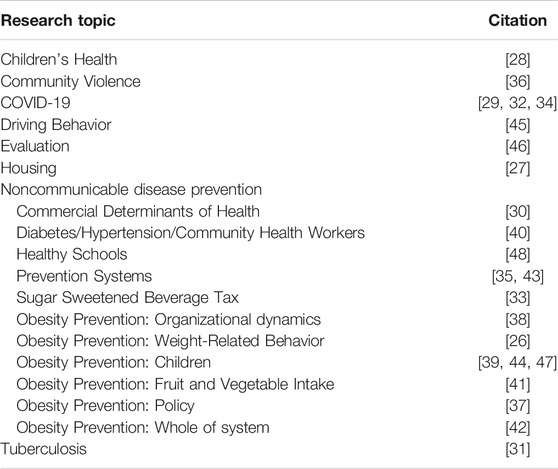

Although the literature addressed a range of public health topics, non-communicable disease prevention was most frequently addressed (15/23) and of those, seven were focused on obesity prevention. Table 2 provides a list of research topics.

In terms of research aims found in the 23 articles, four themes emerged: 1) to examine the complexity of a public health topic and illustrate complex systems thinking [26–34]; 2) to discuss the complexity of a public health intervention [35–40]; 3) to describe study protocol and how CLDs were created [41–44]; and 4) to illustrate how CLDs can be used to monitor and track initiatives to improve population health or evaluate impact of interventions [45–48].

Complex Systems Thinking

Complex systems thinking was discussed in terms of systems, problems, interventions, and key concepts that drive this type of approach. Several articles indicated that the systems they were studying were complex, for example:

A complex system may be characterized by its heterogeneity (various actors and structures at different levels); its dynamic, interactive, and adaptive nature (its ability to respond to or resist external changes, or changes in the interacting parts); and its emergent properties (arising through interactions between processes or factors that alone do not exhibit such properties) [30].

Following on this, feedback loops in complex systems were explicitly discussed in all articles to some extent. Jalali et al. [38] described these in terms of “causal chains of multiple variables in which changes in each variable could be traced back to its historical values.” They go on to define the difference between reinforcing and balancing feedback loops.

Another way complex systems thinking was described was with respect to complex problems and interventions. Burrell et al. [36] discussed community violence in terms of embedded contexts and the lack of holistic understanding of such “dynamic complexity.” Complex problems and interventions were often discussed together. The need to move away from “isolated intervention thinking” to systemic interventions to study systems change was highlighted by Knai et al. [30].

All articles built upon the descriptions reported above in some manner when discussing complex systems thinking. Some articles described this as providing “the opportunity to understand, test, and revise our understanding of how the different components in a system work together” [31] and “to study complex problems as the manifestation of dynamic interactions among their constituent parts” [36]. Furthermore, a few articles expanded the discussion to include such concepts as boundary judgement [38, 43, 47], that is, “establishing boundaries to the system is a fundamental starting point to efforts to change systems” [47].

Why Causal Loop Diagrams?

CLDs were mostly seen as a means or a tool to examine feedback at play in public health issues. Some articles were explicit [28, 32, 33, 40, 43, 44] while others implied this. Both Riley et al. [43] and Parmar et al. [40] labeled this as “causal loop analysis” and the resulting CLDs were a means to understand systems and potential “programming.” Using a CLDs was a new tool for some [42, 46] and as one article related, “business as usual” was not working to address obesity [47]. CLDs were also considered a tool to help tell a story. For example, a CLD was thought to support the development of “a concise narrative about a particular problem” [42] and Brereton et al. [28] stated that “every causal loop tells a story that links cause and effect through feedback.”

How Were Causal Loop Diagrams Created?

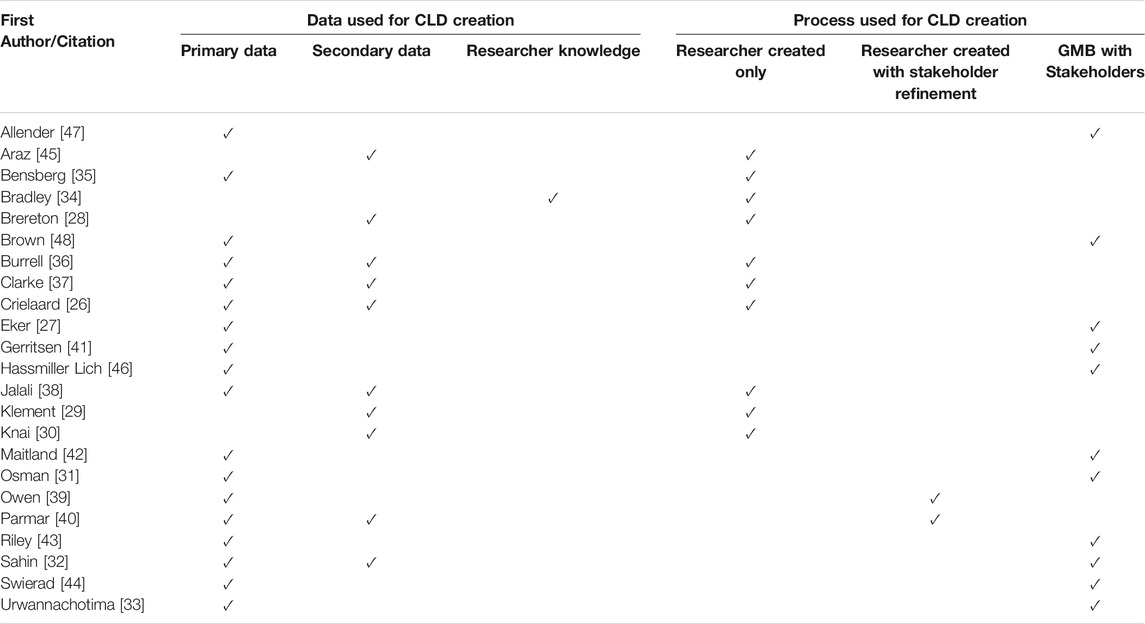

There were many combinations of methods used to create CLDs. In this section we present this diversity in terms of 1) data sources, 2) processes, 3) data analysis, 4) frameworks, and 5) diagramming (Table 3).

Data Sources

Both primary and secondary data were used for creating CLDs (Table 3). Most articles reported on primary data collection (18/23) and this included interviews [26, 27, 33, 35–40], group model building with stakeholders and/or community members [32, 41, 43, 44, 46, 48], behavioral data [42, 47], fieldnotes [37], and workshops with experts [31]. Twelve articles used primary data only.

Secondary data was used in 10 articles [26, 28–30, 32, 36–38, 40, 45] and this consisted of document and/or literature review (Table 3). Of the eighteen articles that reported on primary data collection, six included document review [26, 32, 36–38, 40]. Documents included policy briefings, reports, consultation papers, and evaluation reports [37], documentaries and ethnographies [36], program data [38], geographical information and government documents [32], and data from published databases [28, 37, 45]. Literature reviews were undertaken in four articles and these either supplemented primary data [26], secondary data [28, 45], or both [36]. Document and literature review were utilized in four articles [28–30, 45].

Processes

There were three processes used to create CLDs: group model building, researcher created only, and researcher created with stakeholder refinement (Table 3). Group model building (GMB) was the most common process as reported in 11 articles [27, 31–33, 41–44, 46–48]. Urwannachotima et al. [33] described GMB as “an established methodology for engaging stakeholders to gain mutual understanding of complex relationships and to collectively develop comprehensive systems models that represent the cause and effect relationships of a problem.” They go further to explain that “stakeholders are deeply and actively involved in the process of model construction through the exchange, assimilation, and integration of mental models into a holistic system description.” GMB was generally reported to be a process where participants brainstormed and named potential variables, drew connections and feedback loops between the identified variables, and then mapped these ideas onto a final CLD. However, there was a variety of GMB processes used and was often not clearly described in terms of session design and activities. Beyond GMB, Hassmiller Lich et al. [46] discussed group concept mapping and Gerritsen et al. [41] described graphing over time and cognitive mapping.

CLDs created by researchers only was the second most common process (10/23). Two articles reported that CLDs were presented to stakeholders for refinement [39, 40]. The range of approaches included:

• Using coded interview data to map interactions between key variables [26, 35–38],

• Conducting a literature review to compare causal links uncovered in interview data [26] or a document review [29, 30],

• Completing both a literature review and a document review to identify variables [28, 45],

• Building on an existing CLD [29], and

• Creating a CLD solely from researcher knowledge and expertise [34].

Data Analysis

Overall, we found that description was often lacking regarding qualitative data analysis methods used. However, some articles [35, 37, 39] that collected primary data discussed methods described by Kim and Anderson [49]. Others such as Owen et al. [39] created a table to demonstrate how they used coded interview transcript statements to inform their CLD. Steps in the analysis included 1) using coded text to show causal linkages, 2) translating these to cause-and-effect variables, and 3) creating word-and-arrow diagrams for CLD use. Similarly, Brereton and Jagals [28] presented a table to identify variables and describe influencing links.

Frameworks

Several articles applied specific frameworks to inform research. For example, Allender et al. [47] used Foster-Fishman’s [50] theoretical framework of six elements (i.e., systems norms, financial resources, human resources, social resources, regulations, and operations) to study root causes, system interactions, and levers for change. Similarly, Baugh Littlejohns and Wilson’s [5] framework of seven attributes of effective prevention systems (i.e., leadership, resources, health equity paradigm, information, implementation of desired actions, complex systems thinking, collaborative capacity) was used by Bensberg et al. [35] in their study design.

Diagramming

Many articles reported on the use of software for creating the actual diagram. Vensim [31, 35, 37, 39, 40, 44–46], Stella Architect [28], and STICK-E [43] were the three diagrammatic programs used. Further to the actual diagram, there was a wide array of CLD types and degrees of diagram readability. We found that some CLDs were kept quite simple, with fewer variables, arrows, and loops, while others were very complicated. For example, Brereton et al. [28] created a tightly packed and dense color-coded main CLD and six diagrams of various feedback loops to highlight key variables, relationships, and potential leverage points. Overall, we found that key variables in blocks or shapes, labelled arrows and feedback loops, color coding, legends, and clear diagram interpretation descriptions were important aspects for readability.

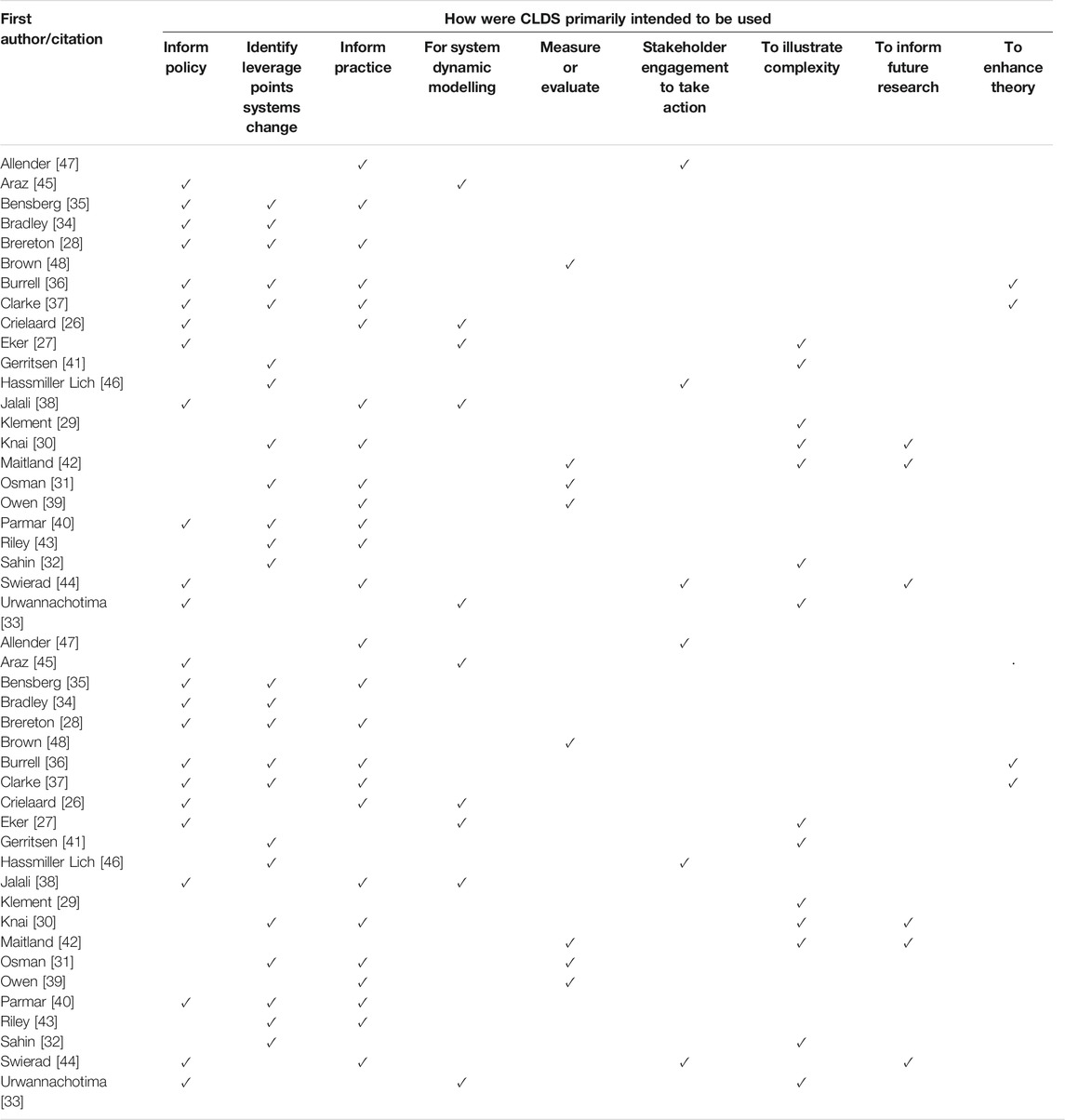

Intended Uses of Causal Loop Diagrams

There were nine ways that CLDs were intended to be used and these are identified in Table 4. The following provides examples of each intended use.

Illustrate Complexity and Identify Leverage Points

Illustrating complexity was aligned with research aims in several articles (Table 4) and was implicit in the other articles with respect to using CLDs. Identifying leverage points was explicitly discussed in twelve articles. Osman et al. [31] found that key variables and their interactions pointed to strategies to enhance leadership “through a reduction in bureaucracy in the health system.” Similarly, Bensberg et al. [35] identified leadership as a leverage point as well as knowledge and data, resources, workforce, and collaborative relationships that need to be “nudged in the desired direction.” One of the more detailed descriptions of leverage points was from Sahin et al. [32]. They adapted Meadows [51] framework of places to intervene in system to identify shallow or deep leverage points to address the “wicked complexity” of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inform Policy and Practice

Informing policy was a reported intended use of CLDs in twelve articles (Table 4). Some articles were detailed in offering policy directions while others simply stated that the CLD could inform policy. Clarke et al. [37] examined “key influences on policy processes, and to identify potential opportunities to increase the adoption of recommended policies” with respect to a state government obesity prevention initiative. Other examples include the need for policies to address population growth, family size, and family planning to improve child health [28], housing, energy and wellbeing [27], and sugar-sweetened beverage tax to reduce sugar consumption and dental caries [33].

Informing practice was also a frequently identified intended use of CLDs (13/23) (Table 4). For example, Osman et al. [31] stated that their CLD could be used “to develop local action plans for implementation and consider strategies for mitigating possible future risks” and Parmar et al. [40] to develop “strategies to enhance capacities, services, and coordination to improve the health of refugees.”

For System Dynamics Modeling

Five articles created CLDs for use in system dynamics modeling [26, 27, 38, 45] (Table 3). This was defined by Araz et al as “a computer-aided approach to model and facilitate analysis of complex system behaviors over time” [45]. They further described the steps in system dynamic modeling, and this was very much in line with other articles:

We first constructed a causal loop diagram (CLD) informed by the existing literature to present the causal relationships between variables in drugged driving behaviors and traffic safety policies. A stock-flow diagram (SFD) was then used to convert these dynamic processes into quantitative expressions and a simulation tool [45].

Mirroring the above descriptions, Crielaard et al. [26] discussed the value of system dynamic modeling in terms of testing policy options from “studying ‘what if’ scenarios using computational modelling approaches.” It was notable that Urwannachotima et al. [33] and Swierad et al. [44] stated that the primary value of CLDs was in quantitative modelling.

Measure and Evaluate Systems Change

Table 4 identifies four articles that used CLDs to help measure and evaluate systems change [31, 39, 42, 48]. For example, Owen et al. [39] reported that “the methods provide a technique to retrospectively evaluate community interventions from a systems perspective and understand the way successful and unsuccessful interventions addressed complexity.” They go further to explain that CLDs go beyond linear cause and effect logic models used in traditional evaluation and lessons regarding unintended consequences provide insights “to increase the chances of success for new prevention initiatives.”

Enhance Stakeholder and Community Participation

As discussed above, group model building (GMB) was a frequently reported process to create CLDs and inherent in these processes was the desire for stakeholder and/or community participation and shared understanding (Table 4). Gerritsen et al. [41] stated what many others did, that is, GMB helped people develop an understanding of the system under study and that “participants learn to see causal connections and how these connections result in patterns of behaviour evolving over time.” They hypothesized that resulting plans for system change would be more successful with this fundamental level of participation and understanding. Another article highlighted that GMB brought diverse stakeholders “together to develop a system understanding of the problem, thus paving the way for further collaboration and community action” [44].

Inform Future Research and Enhance Theoretical Perspectives

The final two intended uses of CLDs were to inform future research and enhance theoretical perspectives (Table 4). These intended uses were not widely discussed and if at all, they were mostly short aspirational statements. However, one example where future research was explicitly discussed was provided by Swierad et al. [44]. Here they reported that “hypotheses” from a CLD of childhood obesity could be used in future research such as “impact of food eaten at school influencing norms and acceptability of western/packaged food, elasticity of grandparents’ food norms, diversity of grandparents’ ideal body image for children, or beliefs in health of traditional foods.”

With respect to using CLDs to enhance theoretical perspectives, Clarke et al. [37] suggested that the CLD “enhanced previously published theoretical analyses of obesity prevention policy decision-making systems by making explicit how underlying feedback loops either spurred policy change or resistance.” Another example is from Burrell et al. [36]. They reported that creating a CLD resulted in “a testable ecologically oriented theory of violence” and “the resulting model conveys new theoretical insights on how racial and economic features of urban settings interact with intrapsychic dimensions to create a self-perpetuating system of violence.”

Discussion

This section answers our second research question: What recommendations emerge regarding how to create and use CLDs in public health research? We offer nine learnings from the results above and interweave ideas from other research to support preliminary recommendations or possible directions to take forward in future research.

Boundary Judgements

We learned that some articles described in detail theoretical orientations with respect to complex systems thinking while others gave brief explanations. The most frequent concepts regarding complex systems were the inherent dynamic interactions among many entities, factors, variables that illustrate whole system structure and behavior. This is consistent with other public health literature on the topic [52–54]. The difference in descriptions was more a matter of comprehensiveness than definitions. For example, boundary judgement was not well articulated in the articles. According to Ulrich [55], drawing boundaries builds in selectivity and partiality and therefore transparency is important in study design. Therefore, we recommend that attention be given to defining boundaries to signal a specific endogenous perspective and a unique, snap-shot-in-time diagram of feedback loops of system behavior [56].

From Theory to Leverage Points

Some articles had strong theoretical coherence with respect to complex systems thinking that was demonstrated in discussions about the reasons for choosing, creating, and using CLDs. We learned that articles were most coherent when they first discussed feedback loops from a theoretical perspective and then carried this through to creating CLDs and to using them to identify leverage points for systems change (see for example 30). Overall, the descriptions of feedback in the articles were aligned with the idea that CLDs are “the applications of the loop concept underlying feedback and mutual causality” and that feedback loops are “powerful unifying notions that illuminate the structure of arguments, explanations, and causal views” [56]. Meadows [51] is well-known for explaining that disrupting or amplifying feedback loops can be effective leverage points in systems change. Therefore, we recommend that future research be designed with this theoretical coherence in mind.

Theoretical Frameworks

Lewin’s famous statement that “there is nothing so practical as good theory” was salient for what we learned [57]. Few articles used theoretical frameworks in research design or discussed the need to advance theory (i.e., complexity, systems) in public health research. The articles that used frameworks appeared to be more robust especially with respect to embedding theoretical constructs in the resultant CLD (see for example 35). While we appreciate that theory is emerging, we recommend that this be given more emphasis to help continue to build a solid foundation for furthering the application of CLDs in public health research.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Knai et al. [30] pointed out that current public health research “concentrates mainly on a system’s elements rather than the interconnections within it, and this is beginning to reveal its intrinsic limitations.” Some articles described data analysis methods to identify variables and examine interconnections to draw CLDs, however, others lacked clear descriptions of the often highly iterative methods and therefore it was difficult to follow a data trail and assess the resultant CLD. We recommend that more clarity be provided as to how researchers innovate in qualitative data analysis to further develop the art and science of creating CLDs.

Mixed Methods

We found a range of research methods used to create CLDs. Ozawa et al. [58] state that mixed methods research is important

because it allows researchers to view problems from multiple perspectives, contextualize information, develop a more complete understanding of a problem, triangulate results, quantify hard-to-measure constructs, provide illustrations of context for trends, examine processes/experiences along with outcomes and capture a macro picture of a system.

We hypothesize that mixed methods may produce more robust CLDs, however, this needs to be examined. We recommend that future research be undertaken to assess the strengths, limitations, and benefits of using mixed methods and determine what methods create greater confidence in the variables and feedback loops illustrated in CLDs.

Participatory Action Research

We found there was a wide range of who was involved in creating CLDs, from researchers only to multiple group model building sessions with stakeholders and community members. We see the latter methodology embedded in the traditions of action research [59] and/or community-based participatory research (CBPR) [60]. The CBPR approach involves “a commitment to conducting research that shares power with and engages community partners in the research process” and is intended “to increase knowledge and understanding of a given phenomena and integrate knowledge gained with interventions and policy and social change” [60]. There was little discussion of CBPR in the articles. We recommend that greater engagement with participatory action research literature be undertaken to embed the theory and philosophy of genuine participation and empowerment in research and action.

Knowledge Translation

There was limited discussion regarding how exactly CLDs were to be used to enhance evidence-informed policy and practice. Few articles explicitly discussed incorporating knowledge users or those able to use research results. As Sturmberg [61] relates, this requires users who are “deeply interested in understanding the highly interconnected and interdependent nature of the issues.” This led us to think about the importance of knowledge translation (KT) and how to strengthen the use of CLDs. Haynes et al. [6] state that KT needs to be conceptualized as not “a discrete piece of work within wider efforts to strengthen public health, but as integral to and in continual dialogue with those efforts.” We recommend that future public health research using CLDs should articulate KT plans that articulates knowledge user engagement in defining outcomes for strengthening public health policies and practices.

Health Equity

We conceptualize public health research to be guided by principles of social justice and human rights to address the goal of reducing health inequities through action on the determinants of health. Although many articles discussed determinants of health, the goal of reducing health inequities was largely absent. Baum et al. [62] discuss the concept of path dependency as “the tendency of institutions to retain policy directions and preferences rather than change or reform them.” They further suggest that disrupting “path dependency that exacerbates health inequities” is critical and we see how CLDs could uncover path dependencies. We recommend that CLDs in public health research should include the examination of leverage points for pro-equity policy and practice.

The Diagram

Senge [63] states that “reality is made up of circles” but often arguments and explanations are linear, therefore, CLDs can provide “a language of interrelationships” to uncover deep patterns in systems. Studying the interrelationships and explanations of each CLD was outside the scope of this paper, however, we learned about some basic elements of reader friendly CLDs. We recommend that the following questions could be used assess CLDs: Are established conventions [56] used effectively for drawing the CLD (e.g., labeling, positive and negative arrows, reinforcing and balancing loops)? Does the diagram illuminate the most significant variables, feedback loops or leverage points? How well does the diagram function as an effective medium for presenting findings to knowledge users? How well does the CLD tell a story of what’s going on in a system?

Strengths and Limitations

In terms of limitations, the 23 articles were not considered to be comprehensive. Since completing the study, we found that Mui and others [64] published an article on a community-based system dynamics approach and suggests solutions for improving healthy food access in a low-income urban environment. We also found Savona et al. [65] identified the views of adolescents regarding the causes of obesity and used CLDs. While this can be considered a limitation, we hope to see a continual building of knowledge and skill in using CLDs in public health research. A strength of this paper is that 23 recent articles were identified that used CLDs and the depth and breadth of discussion in the articles provided good representation. Having three authors conduct the literature review is also a strength because this afforded a high degree of confidence in reporting results and transparency in search strategy and data extraction, analysis and synthesis. Together the results and recommendations can contribute to informing global public health research by highlighting key considerations to help design research and address public health issues through complex systems thinking.

Author Contributions

LB designed the overall research aim and questions and CN provided input throughout the study. Study selection was conducted by LB. Appraisal and duplicate independent data extraction and validation was conducted by two authors (LB and CH). LB and CH completed data analysis and all authors (LB, CH, and CN) provided input into writing the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from Canadian Institutes for Health Research (LB/Postdoctoral fellowship) and the College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan (CH/Dean’s summer research project scholarship). Funding for the open access publication fee will be covered through the Canadian Institutes for Health Research award. The funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Rutter, H, Savona, N, Glonti, K, Bibby, J, Cummins, S, Finegood, D, et al. The Need for a Complex Systems Model of Evidence for Public Health. The Lancet (2017) 390(10112):2602–4. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31267-9

2. Carey, G, Malbon, E, Carey, N, Joyce, A, Crammond, B, and Carey, A. Systems Science and Systems Thinking for Public Health: a Systematic Review of the Field. BMJ Open (2015) 5(12):e009002. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002

3. Chughtai, S, and Blanchet, K. Systems Thinking in Public Health: a Bibliographic Contribution to a Meta-Narrative Review. Health Policy Plan (2017) 32(4):585–94. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw159

5. Baugh Littlejohns, L, and Wilson, A. Strengthening Complex Systems for Chronic Disease Prevention: a Systematic Review. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):729. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7021-9

6. Haynes, A, Rychetnik, L, Finegood, D, Irving, M, Freebairn, L, and Hawe, P. Applying Systems Thinking to Knowledge Mobilisation in Public Health. Health Res Pol Syst (2020) 18(1):134. doi:10.1186/s12961-020-00600-1

7. Egan, M, McGill, E, Penney, T, Meier, PS, Savona, N, de Vocht, F, et al. Complex Systems for Evaluation of Public Health Interventions: a Critical Review. The Lancet (2018) 392:S31. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32053-1

8. McGill, E, Er, V, Penney, T, Egan, M, White, M, Meier, P, et al. Evaluation of Public Health Interventions from a Complex Systems Perspective: A Research Methods Review. Soc Sci Med (2021) 272:113697. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113697

9. McGill, E, Marks, D, Er, V, Penney, T, Petticrew, M, and Egan, M. Qualitative Process Evaluation from a Complex Systems Perspective: A Systematic Review and Framework for Public Health Evaluators. Plos Med (2020) 17(11):e1003368. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003368

10. Rusoja, E, Haynie, D, Sievers, J, Mustafee, N, Nelson, F, Reynolds, M, et al. Thinking about Complexity in Health: A Systematic Review of the Key Systems Thinking and Complexity Ideas in Health. J Eval Clin Pract (2018) 24(3):600–6. doi:10.1111/jep.12856

11. Forrester, JW. Learning through System Dynamics as Preparation for the 21st Century. Syst Dyn Rev (2016) 32(3-4):187–203. doi:10.1002/sdr.1571

12. Forrester, J. Some Basic Concepts in System Dynamics. Boston: Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2009).

13. Baugh Littlejohns, L, Baum, F, Lawless, A, and Freeman, T. The Value of a Causal Loop Diagram in Exploring the Complex Interplay of Factors that Influence Health Promotion in a Multisectoral Health System in Australia. Health Res Pol Syst (2018) 16:126. doi:10.1186/s12961-018-0394-x

14. Paina, L, Bennett, S, Ssengooba, F, and Peters, DH. Advancing the Application of Systems Thinking in Health: Exploring Dual Practice and its Management in Kampala, Uganda. Health Res Pol Sys (2014) 12(1):41. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-12-41

15. Varghese, J, Kutty, VR, Paina, L, and Adam, T. Advancing the Application of Systems Thinking in Health: Understanding the Growing Complexity Governing Immunization Services in Kerala, India. Health Res Pol Sys (2014) 12(1):47. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-12-47

16. Agyepong, IA, Aryeetey, GC, Nonvignon, J, Asenso-Boadi, F, Dzikunu, H, Antwi, E, et al. Advancing the Application of Systems Thinking in Health: Provider Payment and Service Supply Behaviour and Incentives in the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme - a Systems Approach. Health Res Pol Sys (2014) 12:35. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-12-35

17. Biroscak, BJ, Schneider, T, Panzera, AD, Bryant, CA, McDermott, RJ, Mayer, AB, et al. Applying Systems Science to Evaluate a Community-Based Social Marketing Innovation. Soc Marketing Q (2014) 20(4):247–67. doi:10.1177/1524500414556649

18. Allender, S, Owen, B, Kuhlberg, J, Lowe, J, Nagorcka-Smith, P, Whelan, J, et al. .A Community Based Systems Diagram of Obesity Causes. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0129683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129683

19. Homer, J, Milstein, B, Wile, K, Pratibhu, P, Farris, R, and Orenstein, DR. Modeling the Local Dynamics of Cardiovascular Health: Risk Factors, Context, and Capacity. Prev Chronic Dis (2008) 5(2):A63.

20. Brennan, LK, Sabounchi, NS, Kemner, AL, and Hovmand, P. Systems Thinking in 49 Communities Related to Healthy Eating, Active Living, and Childhood Obesity. J Public Health Manag Pract (2015) 21:S55–69. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000248

21. Kopelman, P, Jebb, SA, and Butland, B. Foresight. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices - Project Report. London: Government Office for Science (2007).

22. Munn, Z, Peters, MDJ, Stern, C, Tufanaru, C, McArthur, A, and Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors when Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med Res Methodol (2018) 18(1):143. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

23. Haddaway, NR, Woodcock, P, Macura, B, and Collins, A. Making Literature Reviews More Reliable through Application of Lessons from Systematic Reviews. Conservation Biol (2015) 29(6):1596–605. doi:10.1111/cobi.12541

24. Byrne, JA. Improving the Peer Review of Narrative Literature Reviews. Res Integr Peer Rev (2016) 1:12. doi:10.1186/s41073-016-0019-2

25. Hsiu-Fang, H, and Shannon, SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res (2005) 15(9):1277. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

26. Crielaard, L, Dutta, P, Quax, R, Nicolaou, M, Merabet, N, Stronks, K, et al. Social Norms and Obesity Prevalence: From Cohort to System Dynamics Models. Obes Rev (2020) 21(9):e13044. doi:10.1111/obr.13044

27. Eker, NZ, Carnohan, S, and Davies, M. Participatory System Dynamics Modelling for Housing, Energy and Wellbeing Interactions. Build Res Inf (2018) 46(7):738–54. doi:10.1080/09613218.2017.1362919

28. Brereton, CF, and Jagals, P. Applications of Systems Science to Understand and Manage Multiple Influences within Children's Environmental Health in Least Developed Countries: A Causal Loop Diagram Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18(6). doi:10.3390/ijerph18063010

29. Klement, RJ. Systems Thinking about SARS-CoV-2. Front Public Health (2020) 8(650):585229. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.585229

30. Knai, C, Petticrew, M, Mays, N, Capewell, S, Cassidy, R, Cummins, S, et al. Systems Thinking as a Framework for Analyzing Commercial Determinants of Health. Milbank Q (2018) 96(3):472–98. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12339

31. Osman, M, Karat, AS, Khan, M, Meehan, S-A, von Delft, A, Brey, Z, et al. Health System Determinants of Tuberculosis Mortality in South Africa: a Causal Loop Model. BMC Health Serv Res (2021) 21(1):388. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06398-0

32. Sahin, O, Salim, H, Suprun, E, Richards, R, MacAskill, S, Heilgeist, S, et al. Developing a Preliminary Causal Loop Diagram for Understanding the Wicked Complexity of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Systems (2020) 8(2):20. doi:10.3390/systems8020020

33. Urwannachotima, N, Hanvoravongchai, P, and Ansah, JP. Sugar-sweetened Beverage Tax and Potential Impact on Dental Caries in Thai Adults: An Evaluation Using the Group Model Building Approach. Syst Res (2019) 36(1):87–99. doi:10.1002/sres.2546

34. Bradley, DT, Mansouri, MA, Kee, F, and Garcia, LMT. A Systems Approach to Preventing and Responding to COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine (2020) 21:100325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100325

35. Bensberg, M, Joyce, A, and Wilson, E. Building a Prevention System: Infrastructure to Strengthen Health Promotion Outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18(4):1618. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041618

36. Burrell, M, White, AM, Frerichs, L, Funchess, M, Cerulli, C, DiGiovanni, L, et al. Depicting "the System": How Structural Racism and Disenfranchisement in the United States Can Cause Dynamics in Community Violence Among Males in Urban Black Communities. Soc Sci Med (2021) 272:113469. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113469

37. Clarke, B, Kwon, J, Swinburn, B, and Sacks, G. Understanding the Dynamics of Obesity Prevention Policy Decision-Making Using a Systems Perspective: A Case Study of Healthy Together Victoria. PLoS ONE (2021) 16(1):e0245535. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245535

38. Jalali, MS, Rahmandad, H, Bullock, SL, Lee-Kwan, SH, Gittelsohn, J, and Ammerman, A. Dynamics of Intervention Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance inside Organizations: the Case of an Obesity Prevention Initiative. Soc Sci Med (2019) 224:67–76. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.021

39. Owen, B, Brown, AD, Kuhlberg, J, Millar, L, Nichols, M, Economos, C, et al. Understanding a Successful Obesity Prevention Initiative in Children under 5 from a Systems Perspective. PLoS One (2018) 13(3):e0195141. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0195141

40. Parmar, PK, Rawashdah, F, Al-Ali, N, Abu Al Rub, R, Fawad, M, Al Amire, K, et al. Integrating Community Health Volunteers into Non-communicable Disease Management Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan: a Causal Loop Analysis. BMJ Open (2021) 11(4):e045455. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045455

41. Gerritsen, S, Harré, S, Rees, D, Renker-Darby, A, Bartos, AE, Waterlander, WE, et al. Community Group Model Building as a Method for Engaging Participants and Mobilising Action in Public Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(10). doi:10.3390/ijerph17103457

42. Maitland, N, Williams, M, Jalaludin, B, Allender, S, Strugnell, C, Brown, A, et al. Campbelltown - Changing Our Future: Study Protocol for a Whole of System Approach to Childhood Obesity in South Western Sydney. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):1699. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7936-1

43. Riley, T, Hopkins, L, Gomez, M, Davidson, S, Chamberlain, D, Jacob, J, et al. A Systems Thinking Methodology for Studying Prevention Efforts in Communities. Syst Pract Action Res (2020) 34 (5):555–73.

44. Swierad, E, Huang, TT, Ballard, E, Flórez, K, and Li, S. Developing a Socioculturally Nuanced Systems Model of Childhood Obesity in Manhattan's Chinese American Community via Group Model Building. J Obes (2020) 2020:4819143. doi:10.1155/2020/4819143

45. Araz, O, Wilson, F, and Stimpson, J. Complex Systems Modeling for Evaluating Potential Impact of Traffic Safety Policies: a Case on Drug-Involved Fatal Crashes. Ann Operations Res (2020) 291(1-2):37–58. doi:10.1007/s10479-018-2961-5

46. Hassmiller Lich, K, Urban, JB, Frerichs, L, and Dave, G. Extending Systems Thinking in Planning and Evaluation Using Group Concept Mapping and System Dynamics to Tackle Complex Problems. Eval Program Plann (2017) 60:254–64. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.10.008

47. Allender, S, Brown, AD, Bolton, KA, Fraser, P, Lowe, J, and Hovmand, P. Translating Systems Thinking into Practice for Community Action on Childhood Obesity. Obes Rev (2019) 20:179–84. doi:10.1111/obr.12865

48. Brown, A, Millar, L, Hovmand, PS, Kuhlberg, J, Love, P, Nagorcka-Smith, P, et al. Learning to Track Systems Change Using Causal Loop Diagrams. Obes Res Clin Pract (2019) 13:73–4. doi:10.1016/j.orcp.2016.10.210

49. Kim, H, and Andersen, DF. Building Confidence in Causal Maps Generated from Purposive Text Data: Mapping Transcripts of the Federal Reserve. Syst Dyn Rev (2012) 28(4):311–28. doi:10.1002/sdr.1480

50. Foster-Fishman, PG, Nowell, B, and Yang, H. Putting the System Back into Systems Change: a Framework for Understanding and Changing Organizational and Community Systems. Am J Community Psychol (2007) 39(3-4):197–215. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9109-0

51. Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. Norwich, Vermont: Donella Meadows Institute (1999).

52. Mabry, PL, Marcus, SE, Clark, PI, Leischow, SJ, and Méndez, D. Systems Science: a Revolution in Public Health Policy Research. Am J Public Health (2010) 100(7):1161–3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.198176

53. Finegood, D. The Complec Science of Obesity. In: J Cawley, editor. Handbook of the Social Science of Obesity. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2011).

54. Hawe, P, Shiell, A, and Riley, T. Theorising Interventions as Events in Systems. Am J Community Psychol (2009) 43(3-4):267–76. doi:10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9

55. Ulrich, W. Beyond Methodology Choice: Critical Systems Thinking as Critically Systemic Discourse. J Oper Res Soc (2003) 54(4):325–42. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601518

56. Richardson, G. Feedback Thought in Social Science and Systems Theory. Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications, Inc. (1999).

57. Lewin, K. Action Research and Minority Problems. J Soc Issues (1946) 2:34–46. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x

58. Ozawa, S, and Pongpirul, K. 10 Best Resources on … Mixed Methods Research in Health Systems. Health Policy Plan (2013) 29(3):323–7. doi:10.1093/heapol/czt019

59. Bradbury, H, Reason, P, Publishing, E, and Ebsco, V. The Sage Handbook of Action Research : Participative Inquiry and Practice. 2nd ed. London: SAGE (2012). p. ed2008.

60.B Israel, E Eng, A Schultz, and E Parker, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research in Health. San Fransico, CA: Jossey-Bass (2005).

61. Sturmberg, J. Without Systems and Complexity Thinking There Is No Progress - or Why Bureaucracy Needs to Become Curious. Int J Health Pol Manag (2021) 10(5):227–80. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2020.45

62. Baum, F, Townsend, B, and Fisher, M. Creating Political Will for Action on Health Equity: Practical Lessons for Public Health Policy Actors. Int J Health Pol Manag (2020) x:1–14. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2020.233

64. Mui, Y, Ballard, E, Lopatin, E, Thornton, RLJ, Pollack Porter, KM, and Gittelsohn, J. A Community-Based System Dynamics Approach Suggests Solutions for Improving Healthy Food Access in a Low-Income Urban Environment. PLoS ONE (2019) 14:e0216985–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216985

Keywords: scoping review, causal loop diagrams, public health research, methods, complex systems thinking

Citation: Baugh Littlejohns L, Hill C and Neudorf C (2021) Diverse Approaches to Creating and Using Causal Loop Diagrams in Public Health Research: Recommendations From a Scoping Review. Public Health Rev 42:1604352. doi: 10.3389/phrs.2021.1604352

Received: 16 July 2021; Accepted: 25 November 2021;

Published: 14 December 2021.

Edited by:

Kasia Czabanowska, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Robin van Kessel, Maastricht University, NetherlandsBrian Li Han Wong, Independent Researcher, London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Baugh Littlejohns, Hill and Neudorf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

PHR is edited by the Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) in a partnership with the Association of Schools of Public Health of the European Region (ASPHER)+

*Correspondence: Cory Neudorf, Y29yeS5uZXVkb3JmQHVzYXNrLmNh

Lori Baugh Littlejohns

Lori Baugh Littlejohns Carly Hill

Carly Hill Cory Neudorf

Cory Neudorf