- 1Institute of Health and Society (IRSS), Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

- 2Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 3Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Sciensano, Brussels, Belgium

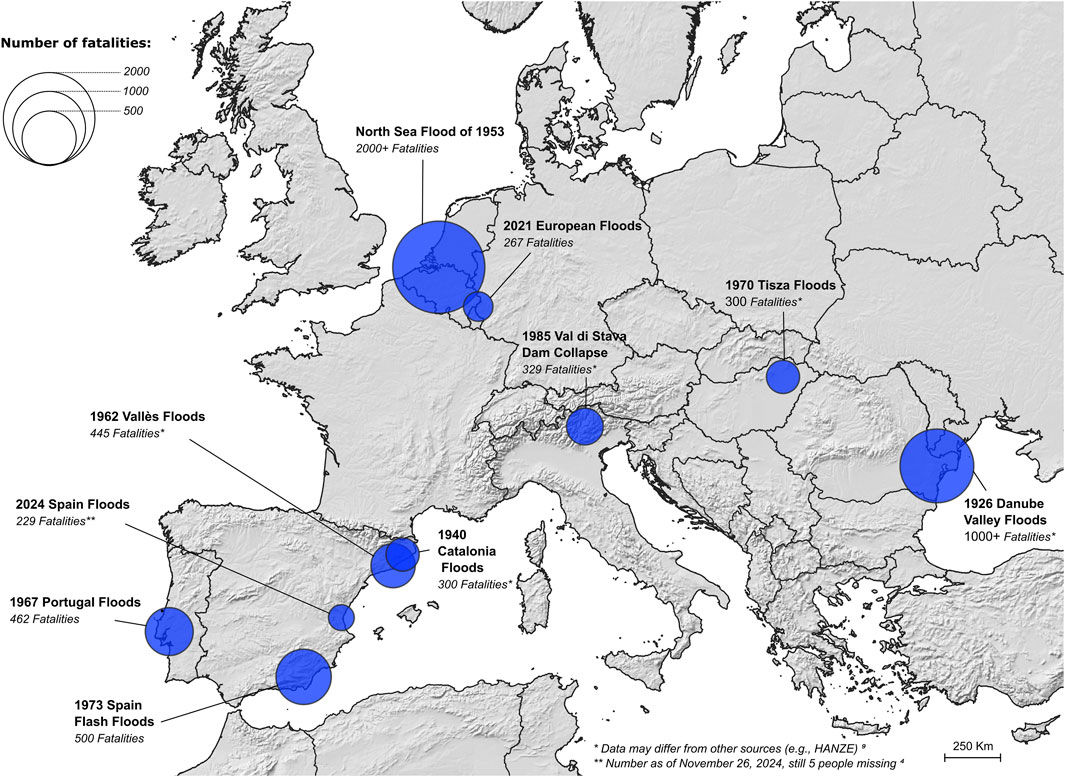

Floods have become increasingly frequent globally, driven by rising sea levels, urbanisation, changes in land use and extreme precipitation [1]. Over the past three decades, floods have caused over 218,000 fatalities, with a third occurring in South-East Asia [2, 3]. Europe has witnessed various severe flooding events, such as the 1926 Danube Valley Floods in Romania, with likely more than 1,000 fatalities; the 1953 North Sea Flood, which inundated the Netherlands, the UK, Belgium, and Luxembourg, resulting in over 2,000 fatalities; and the 1973 Spain Flash Floods, which caused 500 fatalities (Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1. Top-10 deadliest flood events in Europe, 1900–2024, from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) [3].

Most recently, the October-November 2024 Valencia floods in Spain are reported to have caused over 220 deaths, displaced thousands [4], and are considered the deadliest Spanish flood since 1973 (Figure 1). These floods were triggered by gota fría (or “cold drop”), a phenomenon where cold air meets warm Mediterranean waters, leading to intense rainfall.

Flood disasters stem from complex interactions of environmental and human factors. In Spain, as in much of Europe, floods often coincide with other hazards like storms, landslides, or infrastructure failures, causing significant economic and human loss. Preventing future disasters requires understanding the interplay of exposure, vulnerability, and capacity, alongside effective risk communication throughout all stages of disaster management, from emergency response to public awareness. Advancements over recent decades, such as the United Nations’ 2015–2030 Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction [5], the European Union’s 2007 Flood Directive [6], and tools like the European Flood Awareness System [7] have improved preparedness and early warning capabilities.

However, flood risks continue to grow, necessitating stronger evidence-based practices. Databases such as the Emergency Events Database [3, 8] and HANZE [9] are invaluable for analysing past events and identifying links between human, economic and environmental factors.

The 2024 Spain Flood is stark reminder of the need to nurture a culture of proactive risk management, a commitment already established 35 years ago during the 1990 International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction [10]. While tragic, disasters can inspire cultural and governmental dedication to prevention through preparation, coordination and documentation. In embracing resilience through remembrance, we fulfill our duty to honour those affected—both the deceased and the living—with compassion and commitment to a safer future.

Author Contributions

PC and DD developed the first draft with substantial input from NS, JvL, and GP. PC and DD contributed to the subsequent and final versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The EM-DAT project, mentioned in the paper, received financial support from USAID/BHA (Grant number: 72OFDA20CA00072).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Generative AI Statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

1. Sayers, PB, Horritt, M, Penning-Rowsell, E, and McKenzie, A. Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017: Projections of Future Flood Risk in the UK. London: Committee on Climate Change (2015).

2. Liu, Q, Du, M, Wang, Y, Deng, J, Yan, W, Qin, C, et al. Global, Regional and National Trends and Impacts of Natural Floods, 1990–2022. Bull World Health Organ (2024) 102(6):410–20. doi:10.2471/BLT.23.290243

3. CRED. Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) (2024). Available from: http://www.emdat.be (Accessed November 5, 2024).

4. Gobierno de España. Actualización de datos del Gobierno de España. La Moncloa. Available from: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/info-dana/Paginas/2024/261124-datos-seguimiento-actuaciones-gobierno.aspx (Accessed November 26, 2024).

5. UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Geneva, Switzerland: UNISDR (2015).

6. European Parliament and Council. Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the Assessment and Management of Flood Risks (Text with EEA Relevance). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union (2007). http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2007/60/oj.

7. European Flood Awareness System. Data Access. Available from: https://www.efas.eu/en/data-access (Accessed November 11, 2024).

8. Delforge, D, Wathelet, V, Below, R, Sofia, CL, Tonnelier, M, Loenhout, J, et al. EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database. Res Sq Preprint (2025). doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3807553/v2

9. Paprotny, D, Terefenko, P, and Śledziowski, J. HANZE v2.1: An Improved Database of Flood Impacts in Europe From 1870 to 2020. Earth Syst Sci Data (2024) 16(11):5145–70. doi:10.5194/essd-16-5145-2024

Keywords: disaster preparedness, floods, emergency health, climate change, Spain, disaster risk reduction, disaster loss database, Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT)

Citation: Charalampous P, Speybroeck N, van Loenhout JAF, Pluen G and Delforge D (2025) The 2024 Spain Floods: A Call for Resilience and the Duty of Memory. Int J Public Health 70:1608236. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2025.1608236

Received: 10 December 2024; Accepted: 31 January 2025;

Published: 12 February 2025.

Edited by:

Raquel Lucas, University Porto, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Charalampous, Speybroeck, van Loenhout, Pluen and Delforge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Damien Delforge, ZGFtaWVuLmRlbGZvcmdlQHVjbG91dmFpbi5iZQ==

This Editorial is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Disaster Health Convergence: Better Integration of Public Health and Disaster Medicine”

Periklis Charalampous

Periklis Charalampous Niko Speybroeck

Niko Speybroeck Joris A. F. van Loenhout

Joris A. F. van Loenhout Gurvan Pluen1

Gurvan Pluen1 Damien Delforge

Damien Delforge