- 1Department of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań, Poland

- 2Department of Organization and Management in Health Care, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznań, Poland

Objectives: This study was designed to determine the relationship between religion and healthcare practitioners’ attitudes towards conscience clauses in Poland.

Methods: We developed a survey assessing impact of religion on attitudes healthcare professionals towards the conscience clause. These questions were explored using a sample of 300 Polish healthcare professionals.

Results: The results indicate that religiosity was a significant predictor of acceptance of conscience clauses. It also influenced healthcare practitioners’ opinions on medical professionals that should be granted the right to conscience clauses and medical services that may be denied on moral grounds. There was also a significant relationship between healthcare practitioners’ religiosity and their eagerness to use conscience clauses in a situation of moral conflict. Finally, religious healthcare practitioners were more concerned about the personal consequences of using this right in a medical environment.

Conclusion: This study shows that at the same time, both religious and non-religious healthcare professionals believed that the Polish regulations regarding conscience clause are unclear and inaccurate, therefore leading to misinterpretation and abuse regulation of law.

Introduction

One of the pillars of democratic order is the freedom of thought, conscience and religion, guaranteed by international human rights documents [1–3] and national constitutions [4, 5]. Similarly, pursuant to art. 53, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland “Everyone shall be guaranteed freedom of conscience and religion.” This right includes the freedom to choose one’s religion or moral beliefs, the freedom to manifest them individually or with other people, privately or publicly, through worship, prayer, and participation in rituals [6].

Respect for the principle of religious diversity and pluralism of values leads to the idea that everyone has the right to choose any religious, moral or philosophical beliefs he or she identifies with. Problems arise, however, when personal moral beliefs influence social discourse on such bioethical topics as abortion, contraception or euthanasia, which, in turn, may cause moral conflicts among healthcare professionals (HCPs). This may, in turn, hinder the individual right to healthcare. Consequently, every time such issues emerge in public discourse in Poland they provoke a heated debate on the legal sanctioning of the conscience clause (CC) for various medical professions.

The CC itself is a legal norm that, under certain circumstances, allows selected healthcare professionals to refuse to provide a medical service that is permitted by law, but which offends their conscience [7]. It should be noted, however, that the right to the conscience clause differs from the freedom of conscience. While the former is a legal norm that permits the individuals to refuse to perform a medical act that offends their moral beliefs [8], the latter is an ethical norm and a fundamental value which results directly from human dignity [9].

While in the internal realm of thought (forum internum) freedom of conscience and religion remains a matter of individual choice and belief, subject to no restrictions, in the external realm (forum externum) one’s right to manifest these beliefs may be subject to legal restrictions, but only when “public security or order, public health and morality or the freedom and rights of other people are at risk” [6]. Indeed, while there may be good religious, moral, legal reasons to accommodate CC in the context of healthcare practice, it is often argued that the exercise of rights and beliefs of the HCPs may influence patients’ health or access to care services. It is also often claimed that as a result of CC the line between the public and the private space becomes blurred [10, 11].

CC has been included in the provisions of Polish medical law since 1996 and is regulated by art. 39 of the Act on the Professions of Doctors and Dentists, art. 12 of the Act on the Professions of Nurse and Midwife and the Code of Medical Ethics [12–15]. The scope of its application, however, is narrow, as it applies only to selected groups of healthcare professionals: physicians, nurses and midwives.

Although the conditions for using CC are included in the provisions of Polish medical law, this topic continues to be a contentious subject. In fact, the problem comes to the fore every time abortion, contraception and IVF are discussed. It gained momentum, however, in 2014 when nearly four thousand Polish doctors and medical students signed the Declaration of faith of Catholic doctors and students of medicine on the sexuality and fertility of human beings, in which they affirm the Catholic Church’s teaching that all human life is sacred from the moment of conception and declare their refusal to provide abortions, contraception or in vitro fertilization on religious grounds [16, 17].

Unsurprisingly, the document provoked a heated debate and great concerns among Polish society, and, according to the Center for Public Opinion Research, the majority of Poles (73%) believed that even in the case of a conflict of conscience, the physician should not refuse to refer to prenatal tests when there is an increased risk of a genetic or developmental defect in a fetus. Similarly, 62% of respondents believed that a physician should not refuse a referral for abortion if it is not restricted by the law. According to 55% of respondents a physician should not refuse to prescribe contraceptives and 52% believed that he or she should not refuse to perform an abortion when it is legal [18].

Although previous research focused on the opinions of the physicians and medical students much less is known about the attitudes of nurses and pharmacists regarding the conscience clause. While physicians coordinate patient care, other HCPs, including nurses, midwifes and pharmacists face moral dilemmas related to patient care [18–25].

The objective of the study was therefore to examine the association between religion and physicians’, nurses’ and pharmacists’ attitudes towards conscience clauses in Poland. The rationale for choosing these groups rests on the fact that, while in current Polish law CC applies to physicians and nurses, there is an ongoing debate whether pharmacists should also have the right to refuse to dispense drugs related to contraception, and the “morning-after pill” in particular.

At the same time, it should be noted that at the time of this research abortion was legal in Poland on three conditions: when pregnancy poses a threat to the life or health of the pregnant woman, when prenatal tests or other medical indications suggest a high probability of a severe and irreversible impairment in the fetus or an incurable life-threatening disease and when there is a justified suspicion that the pregnancy resulted from a prohibited act, i.e., rape [26]. After the judgment of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal in October 2020 the second premise for allowing legal abortion has been declared unconstitutional and is no longer allowed [27].

According to Polish medical law, a physician is obliged to provide immediate medical assistance to a patient, especially when a failure to do so would pose a threat to the patient’s health or life [12]. The first justification for legal abortion, i.e., when the pregnancy threatens the mother’s life or health, may be considered a compulsory service, which causes no HCPs to invoke CC. There are, however, differences among Polish medical lawyers on this subject [28–30]. The other cases mentioned in the act raise similar doubts. Since there is no clear decision as to whether the above-mentioned legal cases should be treated as mandatory or permitted benefits, we have decided to investigate the opinion of HCPs on this subject.

Methods

Study Design

This research included data from an anonymous, self-administered questionnaire regarding HCPs’ attitudes towards the conscience clause. While it examines the association between religion and HCPs’ attitudes towards CC it was designed as a pilot survey aimed to test questionnaire and see they would respond to the survey design and whether our questions will generate useful results.

Participants and Setting

The study was conducted between January and March 2020 among practicing physicians, nurses and pharmacists in Poznan, Poland. Respondents were recruited during specialization courses or training sessions organized by the Poznan District Chamber of Nurses and Midwives, the Wielkopolska Regional Chamber of Pharmacy and the Department of Gynecological Oncology, Poznan University Hospital of Lord’s Transfiguration. After receiving the final approval an online survey was distributed to physicians, nurses and pharmacists taking their specialization courses and trainings. Each of these courses consisted of 100 participants who agreed to took part in the survey.

Research Tools

A standard questionnaire was used, comprising topics based on literature reviews and the objective of the study. The survey questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part dealt with the demographic characteristics of the study participants. The second part gathered information on the respondents’ opinions regarding the legal aspects of the CC. We asked whether the current law precisely defines a set of rules for HCPs who use the conscience clause, the subject areas of which are not fully regulated, which HCPs should be able to use the CC and for excludes respondents using the CC in cases of legal abortion. The third part of the questionnaire concerned the HCPs’ personal experiences with CC. We therefore asked whether respondents had ever invoked the CC or whether they intended to do so. Respondents were also asked whether they have ever found themselves in a situation that required them to perform professional activities inconsistent with their conscience, and whether employers should have the right to ask about the moral beliefs of the candidates applying for jobs.

Religiosity was measured with one item: the role of religion in personal life. Based on their responses, HCPs were divided into two groups: religious (HCPs for whom religion was important in their life decisions and choices) and ambivalent/nonreligious (HCPs who either declared separation of their religious beliefs from their life decisions and choices or who felt religion was irrelevant to them).

Data Collection

The final version of the questionnaire was distributed among HCPs in several healthcare facilities in Poznan, Poland. All HCPs, received an invitation letter and were informed about the study’s purpose, as well as the voluntary, anonymous, and confidential character of the study. Participants completed self-administered paper-pencil survey. Questionnaires took approximately 20 min to complete and were collected anonymously.

Ethical Issues

The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Although in accordance with local legislation and national guidelines on research involving human subjects, ethical approval was not required it was obtained from the Department of Gynecological Oncology Poznan University Hospital of Lord’s Transfiguration (LBK/63/2018), from the Wielkopolska Regional Chamber of Pharmacy in Poznan (Wlkp. OIA/2711/2018), and from Poznan District Chamber of Nurses and Midwives (OIPIP 15/3/2019). Additionally, ethics approval and research governance approval were obtained from the Poznan University of Medical Sciences Bioethics Committee. Informed consent was also obtained from all respondents enrolled in the study.

Data Analysis

The data collected in the questionnaires were verified and checked for completeness, quality and consistency, and exported into the statistical packages JASP (Version 0.16.1.0) and Dag-stat. The results were presented as descriptive statistics. Tables 2, 6 display the number of responses to individual questions along with the corresponding percentages of the total. A Likelihood Ratio Chi-square was used to assess the differences in the distribution of answers among the groups. A 5% level of significance was used for all the hypothesis tests.

Results

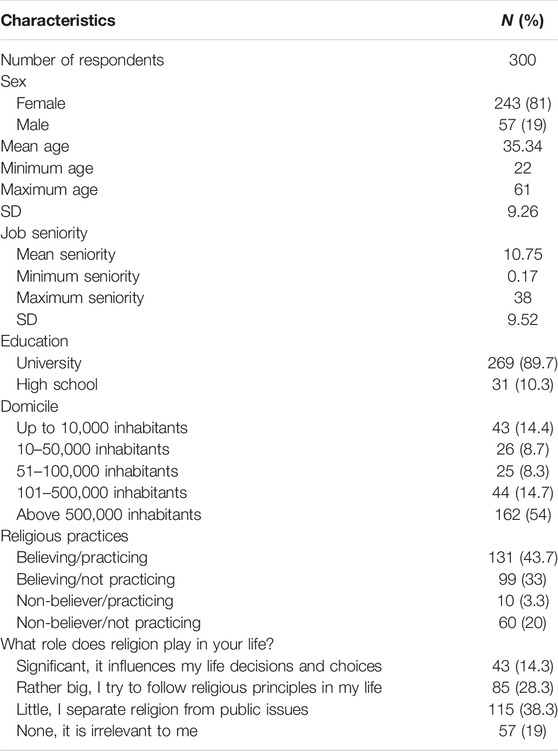

The study group consisted of representatives of three healthcare professionals groups, 100 each of physicians, nurses and pharmacists (Table 1). The majority of respondents were women (81%) with a mean seniority of 10.75 years. Most of our respondents (89.7%) hold a university degree, as, since 2004, the Bologna Process has determined that all HCPs must be university graduates, so only those who began work earlier, e.g., as nurses, may have other qualifications. More than half of respondents (54%) were living in cities of over 500,000 inhabitants. Although the largest group of respondents declared themselves practicing believers (43.7%) only 14.3% declared that religion played a significant role in their life.

At the same time based on HCPs’ declarations regarding their religious beliefs and the role of religion in their life, the respondents were divided into two groups: religious (HCPs who declared that religion influences their life decisions and choices) versus ambivalent/non-religious (HCPs who had no religious allegiences or felt religion was irrelevant to them). The comparison between these two groups showed that they did not differ in terms of sex; however, respondents who declared that religion played an important role in their life tended to come from smaller towns and villages and were older. Nurses were also overrepresented.

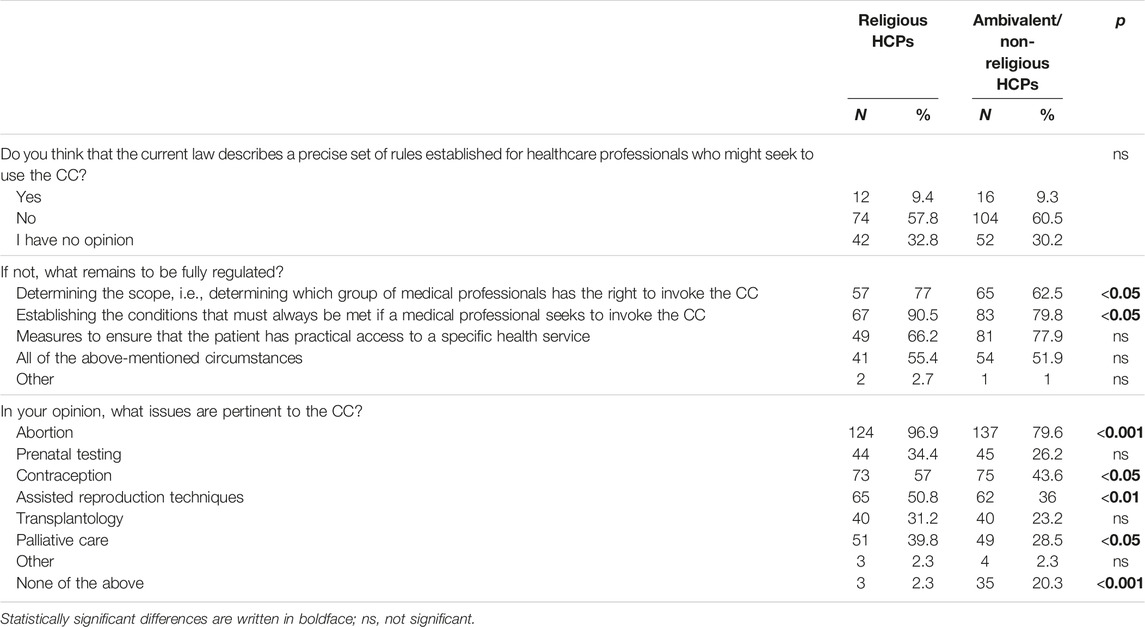

The majority of HCPs in both groups believed that the current Polish law is too imprecise in its definition of the rules that guide their use of the conscience clause (57.8% and 60.5%, respectively) (Table 2). Religious HCPs in particular, however, complained that it remains rather unclear what groups of HCPs have the right to invoke the conscience clause. They also stressed that the conditions necessary for using it should be more precise.

At the same time, HCPs who defined themselves as religious argued that the provision of the conscience clause should mostly be enacted in connection with issues relating to abortion, reproduction, contraception, assisted reproduction techniques and palliative care. Non-religious HCPs, however, frequently declared that none of issues mentioned in the survey should be covered by the CC (20.3% and 2.3%, respectively).

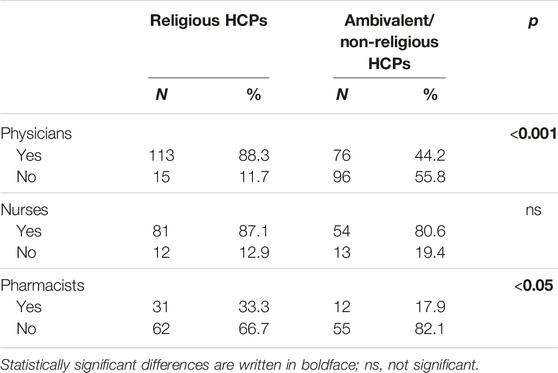

Both groups differed in their opinion regarding which professional groups should be covered by the conscience clause (Table 3). Religious respondents indicated physicians (88.3% vs. 44.2%) and pharmacists (33.3% vs. 17.9%) more often. In reference to nurses no statistically significant difference was found (87.1% vs. 80.6%).

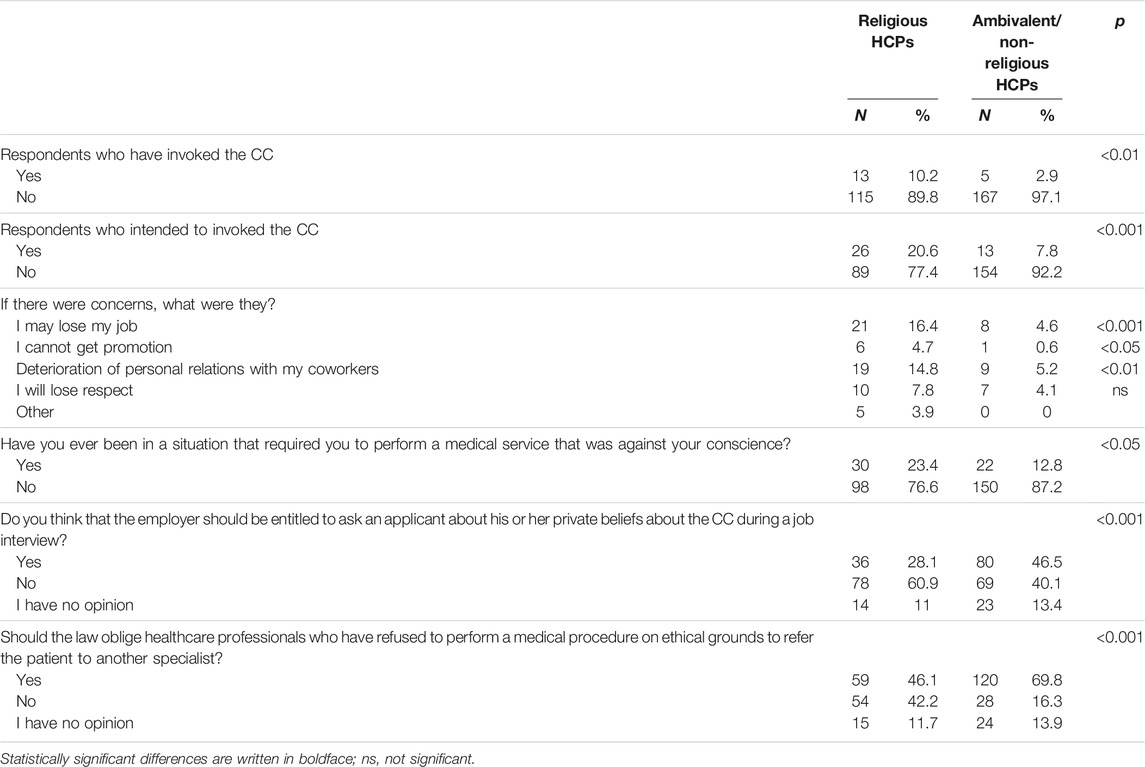

When asked about their personal experience with the CC, it was religious HCPs who declared having exercised the conscience clause more often (10.2% vs. 2.9%). They also intended to do so more frequently (20.6% vs. 7.8%) (Table 4). Religious HCPs were also more concerned about the personal consequences of using this right both in terms of losing their job or being passed over for promotion and deterioration of relations with coworkers. Finally, more religious respondents declared having been in a situation that required them to act against their conscience (23.4% vs. 12.8%)

On the other hand, ambivalent/nonreligious HCPs agreed that the employer should have the right to ask an applicant about his or her private beliefs about the conscience clause during a job interview (46.5% vs. 28.1%), and that the law should oblige those HCPs who have refrained from performing a medical procedure due to ethical objections to refer a patient to another specialist (69.8% vs. 46.1%).

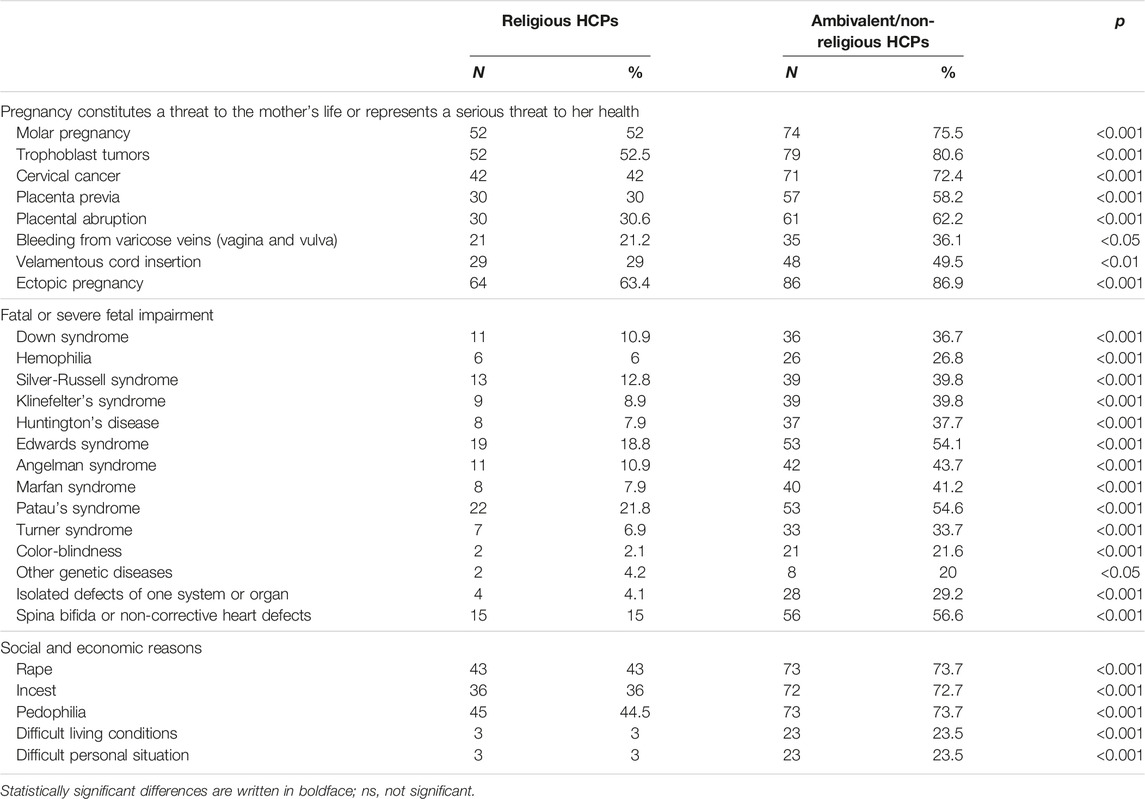

Some significant differences were also found in relation to the reasons both groups felt were legitimate for performing obligatory abortions (Table 5). Ambivalent/non-religious HCPs supported abortion in all three legal cases permitted by Polish law more often. They also supported the procedure for all eventualities.

TABLE 5. Cases in which in the respondents’ opinion HCPs should be unable to invoke the CC (Poland, 2020).

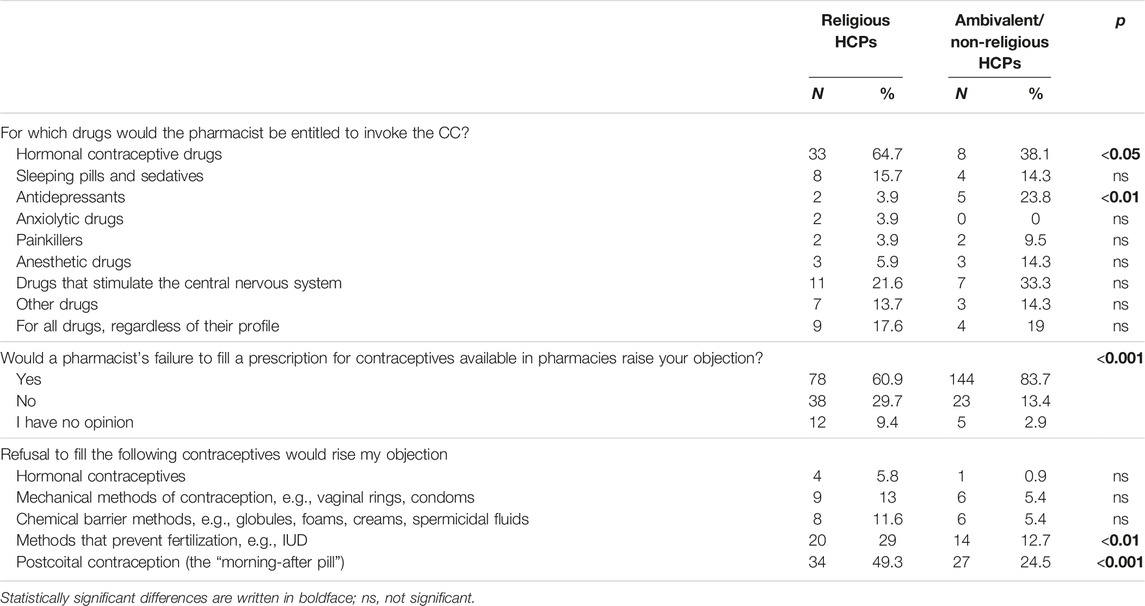

In the case of the CC regarding pharmacists, significant differences have been observed (Table 6). While religious HCPs argued that pharmacists should be granted the right to refuse to dispense drugs related to contraception on moral or religious grounds more often (64.7% vs. 38.1%), ambivalent/nonreligious respondents declared that a pharmacist’s refusal to fill a prescription for birth control would incur their objection (83.7% vs. 60.9%). At the same time, the former indicated an intrauterine device (IUD) (29% vs. 12.7%) and the “morning-after pill” (49.3% vs. 24.5%).

Discussion

Although over the last two decades, there has been a shift in religiosity among Poles, Poland remains an overwhelmingly religious Roman Catholic nation. Indeed, even though the percentage of those who practice regularly has decreased to 43%, still 91% of Poles declare themselves Catholics [31, 32]. Simultaneously, due to secularization and the privatization of religion many Poles are moving towards a more secular view of life, one with a greater separation between the Church and the state, and a rejection of Church mandates on individual morality. Consequently, although religion remains at the core of the value system for many Poles and a source of cultural identification, a “secularization of morality” is to be observed, as the increasing number of Poles feel no need to justify the moral rules of conduct with reference to religion and espouse moral opinions in sharp contrast with their religion [33]. A growing trend towards moral relativism and “situational morality,” may be noticed, as many Poles argue that in some situations moral rules are suspended, that decisions about good and evil are a personal matter and depend on particular circumstances [34]. However, this should not surprise since similar situation was observed in other countries where churches influenced discussion and legislation on such issues as (sexual) education, abortion, divorce, stem cell research, or same-sex marriage, often despite mass social protests [35, 36].

At the same time studies suggest that religiosity still influences HCPs’ attitudes towards patients. For example, Pawlikowski et al. showed that religious faith influences physicians’ professional decisions and is an important coping resource in difficult professional situations. While religious ideas may inspire some to become physicians, religiosity correlates positively with altruism, empathy and holistic encounters with patients, they may clash with respect for patients’ autonomy [37].

The importance of religiosity in making therapeutic decisions and empathetic approaches was also found among nurses [38]. Wenger and Carmel also demonstrated that physicians’ religiosity might affect their end-of-life views which, in turn, directly translate into attitudes towards end-of-life care and influence the way their patients die. Very religious physicians were more likely to continue life-sustaining treatment and were also less eager to withdraw care from their patients. They were also less likely to approve prescribing necessary analgesia if it might hasten patients’ death [39]. Both Balslev van Randwijk et al. and Emanuel et al. found that religiosity and spirituality determine physicians’ attitudes toward such end-of-life procedures as euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, sedation into unconsciousness in dying patients and withdrawal of life support [40, 41]. These conclusions were also confirmed by research from Canada. Brown et al. believe that faith and spiritual beliefs are an important factor influencing the lack of participation of the surveyed physicians and nurses in formal medical assistance in dying processes. Some HCPs have advocated aligning their clinical practice with faith or spiritual beliefs because they provide a source of moral responsibility as well as inner strength and comfort with dying and death [42].

Other research suggest that religiosity is a powerful predictor of HCPs’ willingness to perform abortions [43]. Davidson et al. found that pharmacists’ religiousness affected their willingness to dispense contraceptives and abortion medications [44]. Davis et al. showed that nurses who declared their ethical beliefs to be founded on their religion experienced higher levels of moral anxiety than nurses whose beliefs were shaped by more secular factors, such as family values, political views or a professional code of ethics [45]. Finally, a study by Domaradzki and Walkowiak showed that medical students’ religiosity played a key role in determining their motivations to join the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, as those who declared themselves religious tended to be inspired by altruistic motivations rather than by personal or selfish motives [46].

This research confirms findings from other European countries, such as Italy, where approximately 70% of HCPs including physicians, nurses and midwives, and medical students support the CC [25, 47]. For example, over 45% of medical students in the United Kingdom [20], 79.2% in Spain supported HCP’s right to CC [22], as did 89.0% of Slovakian pharmacists and pharmacy students [48]. A Polish study conducted by Baranowska et al. showed that 65% of pharmacy students and 50% of practicing pharmacists were in favour of introducing CC for pharmacists [49].

According to the participants of the study, CC is rarely utilized in Poland. Respondents also declared that they find it extremely hard to use CC in the context of healthcare practice. While in Slovakia, too, only 32.5% of pharmacists declared having implemented CC in practice [48], studies conducted by Lamb et al. also showed that, although Canadian nurses in Ontario expected the right to CC, they complained over lack of support, especially in situations related to conflicting viewpoints with colleagues and professionally sanctioned practices, such as medical assistance in dying [50, 51]. Many HCPs enrolled in this study would nevertheless be willing to use their right to CC. Piecuch et al. similarly showed that, although 92% of Polish pharmacists have never refused to fill a prescription due to their beliefs, 15% would exercise this right if it were legal [52].

Another important finding is that in accord with previous studies this research shows that among the reasons for accepting HCPs’ right to CC were carrying out or assisting in (early) abortions, euthanasia and assisted reproduction [48, 53]. At the same time, according to our respondents, contraception came second to abortion as a reason HCPs should be entitled to invoke CC. This right was also recognized by both religious and non-religious respondents (57% and 43.6%, respectively). Post-coital contraception or the “morning-after pill” and intrauterine contraceptive devices (ICD) were therefore indicated as products pharmacists should have the right to refuse to sell on the basis of their conscience. This supports findings from a previous study conducted by Piecuch et al. who demonstrated that, according to Polish pharmacists, medical products that should be subjected to CC were primarily emergency contraception (65%), vaccines (46%), intrauterine devices (27%) and hormonal contraception (21%). Similar results were also found in other European countries, such as England, Italy, Portugal and Norway which have similar provisions regarding the legal regulation of CC [54].

On the other hand, this research shows that many HCPs in Poland still believe that HCPs should not be allowed to refuse to perform a medical service which is permitted by the law, but which offends their conscience or personal beliefs. For example, although the majority of Norwegian medical students would object to participating in euthanasia (89%), abortion (55%) or ritual circumcision for boys (52%), many believed that physicians should not be allowed to refuse to participate in such procedures on the grounds of conscience and their general tolerance towards CC was low [21]. Similarly, 70.8% of Spanish students would not invoke CC in cases of abortion; 70% believed that it might have harmful consequences for pregnant women [22]. According to Shaw and Downie, nurses who declare themselves to be religious tend to consider their right to CC more important than the patients’ healthcare rights [55].

Respondents therefore seemed to be aware of their dual commitment toward their conscience and HCPs’ obligations towards patients’ health and rights. For that reason many declared that HCPs must somehow safeguard both HCPs’ right to CC and patients’ (reproductive) rights and health [10]. Piecuch et al. also found that, while 73% of Polish pharmacists believed that pharmacists should not have the right to CC, respondents who supported the implementation of the CC would grant this right only if the pharmacists were obliged to present other real options to the patient about obtaining a specific product. Similarly, the majority of Polish society argues that in the case of a conflict of conscience the physician cannot refuse to prescribe contraceptives or perform an abortion when it is legal [18].

While in some European countries, i.e., United Kingdom, an additional system for monitoring healthcare services has been implemented, respondents from this study claimed that during the job interview employers should not have the right to ask HCPs about their personal beliefs and medical services or pharmaceutical products to which they may have ethical objections [56–59]. They were also concerned that refusal to perform some procedures might cost them their jobs and provoke conflicts with other HCPs.

Most importantly, this research shows that religion has the greatest influence on shaping HCPs’ attitudes towards CC. For example, studies conducted among pharmacists in the United Kingdom by Cooper et al. and Maxwell et al. revealed that religion might affect their ethical attitudes towards selling emergency hormonal contraception [60, 61]. A study by Toro-Flores et al. conducted among Spanish nurses also demonstrated that nurses who declared themselves believers supported CC much more often, in thirteen out of eighteen possible cases, including abortion within the first 14 weeks of pregnancy, voluntary sterilization, the dispensing of the morning-after pill, voluntary abortions in cases when the pregnancy occurred due to rape or when there is the assumption of fetus malformation or when there is a health risk to the mother [53]. A recent study among Greek nurses by Voultsos et al. also showed that religion, along with the quality of education received and upbringing, were the factors that had the greatest impact on the choice of values shaping the morality of the respondents, also in the field of conscientious objection. However, raising ethical objections in the workplace is related to the experience of lack of support and suboptimal communication, which increase fears of bullying and negative gossip, creating a barrier to exercising the principle of conscience clause [62].

At the same time, Bouthillier and Opatrny showed that physicians’ refusal to participate in medical aided dying was not based on moral or religious grounds, but rather resulted from the emotional burden related to this act and the fear of psychological repercussions [23]. Strickland also demonstrated that while 45.2% of future doctors believed that physicians should be entitled to conscientiously object to any procedure for which they have a moral, cultural or religious disagreement, the majority of the objections were for non-religious reasons [20]. Finally, a systematic review conducted by Fleming et al. indicated that the main reasons for or against CC to abortion provision expressed by nurses or midwives were moral reasons which exceeded practical, religious and legal reasons [63, 64].

Although this research showed that of twenty seven possible reasons for abortion there were significant difference in all of them, and that religion was the main predictor for those differences, it should also be noted that neither religious nor non-religious respondents accepted or rejected all the indications. Just as religious HCPs did not close their minds to mandatory abortion for all reasons, so non-religious respondents were unwilling to accept the procedure in all situations approved be the law.

This study therefore shows, that HCPs’ attitudes towards CC is much more complex and cannot be explained solely on the basis of the respondents’ attitudes towards religion. A detailed analysis of their answers indeed suggests that respondents opinions on the admissibility of abortion depends on particular circumstances and reflect what was said about situational morality. HCPs’ acceptance or rejection of abortion is some situations, i.e., ectopic pregnancy, certainly does not automatically entail their acceptance or rejection of other situations, i.e., cervical cancer. This supports findings from a previous study, which demonstrated that, while many Polish gynecologists accepted performing abortions due to lethal defects (46%) or serious diseases in the mother (34%), only 21.1% referred to the religious aspect of abortion and 6% claimed that the procedure offended their conscience [24].

Study Limitations

Although to the best of our knowledge this is one of the few studies on the attitudes of Polish HCPs towards CC, it has limitations which may have an impact on their generalizability and interpretation. Firstly, although this survey was designed as a preliminary study, still only 300 HCPs, which may have an impact on whether the results might be extrapolated and interpreted. Consequently, while this study represents solely the opinions of those HCPs who agreed to participate in the study it would be desirable to compare the findings with those from a survey conducted on a larger sample size. Secondly, HCPs from only one Polish city were enrolled in the study. The study therefore has a local dimension. Thus, it would be desirable to compare the findings from other parts of the country. Thirdly, because the COVID-19 pandemic hindered the recruitment process and reduced the number of respondents who took part in the specialization courses or training sessions the results cannot therefore be extrapolated for the entire population of HCPs either in Poznan or in Poland as a whole. Consequently, it would be desirable to compare the findings from larger group. Fourthly, since this study rests on the quantitative method only, to understand better the association between religion and healthcare practitioners’ attitudes towards conscience clauses further in-depth studies using qualitative methods would be required. Finally, because respondents were not asked specific questions regarding their religious beliefs, their religiosity was assessed on their declarations alone. Thus, future studies should also use well-validated instruments to measure religiosity.

Despite these limitations, however, this study also enjoys some advantages. Most importantly, as there is a scarcity of previous work on the topic, this research helps fill the gap in the research on the attitudes of Polish HCPs towards CC and it may stimulate further research on the topic.

Conclusion

While this study shows that HCPs’ religiosity was a significant predictor of acceptance of CC, it also influenced their opinions on healthcare professions who they feel should hold the right to CC and medical services that might be denied on moral grounds. None of these groups, however, was homogeneous, as, while some religious HCPs believed that some medical services, i.e., contraception, assisted reproduction techniques or palliative care should be excluded from those that might permit HCPs from invoking CC, some non-religious HCPs supported the right to conscious objection. Religious HCPs also admitted to having used CC more often and being willing to do so in a situation of moral conflict. Finally, they were more concerned over the personal consequences of using the right to CC in a medical setting. At the same time, both religious and non-religious HCPs believed that the Polish regulations regarding CC are unclear and inaccurate.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and, in accordance with local legislation and national guidelines on research involving human subjects, ethical approval was not required. Since some participants asked for such approval, however, it was obtained from the Department of Gynecological Oncology Poznan University Hospital of Lord’s Transfiguration (LBK/63/2018) from the Wielkopolska Regional Chamber of Pharmacy in Poznan (Wlkp. OIA/2711/2018) and from Poznan District Chamber of Nurses and Midwives (OIPIP 15/3/2019). Ethics approval and research governance approval were also obtained from the Poznan University of Medical Sciences Bioethics Committee. Informed consent was also obtained from all respondents enrolled in the study.

Author Contributions

JC supervised the conceptualization of the study, designed the research questionnaire and collected the data. DW performed the statistical analyses. JC and JD conducted the literature search and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant obtained for young scientists in the Faculty of Health Sciences, Poznan University of Medical Sciences: The right to freedom of belief and the professional liability of healthcare professionals (502-14-44065120-10593).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the HCPs who participated in the study.

References

1. United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Available From: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/udhr.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

2. Council of Europe. European Convention on Human Rights (1953). Available From: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

3. United Nations. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976). Available From: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/ccpr.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

4. Safjan, M. Wolność Religijna W Konstytucjach Państw Europejskich. In: J Krukowski, and O Theisen, editors. Kultura I Prawo: Materiały III Międzynarodowej Konferencji Na Temat „Religia I Wolność Religijna W Unii Europejskiej” (2003). Warszawa: Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego (2022).

5. Waszczuk-Napiórkowska, J. Opinia Prawna Dotycząca Wolności Sumienia W Konstytucjach Krajów Unii Europejskiej. Zeszyty Prawnicze (2012) 3(35):231–3.

6. KONSTYTUCJA. Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej (1997). Available From: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/prawo/konst/polski/kon1.htm (Accessed August 9, 2023).

7. Galewicz, W. Jak Rozumieć Medyczną Klauzulę Sumienia? Diametros (2012) 34:136–53. doi:10.13153/diam.34.2012.503

8. Głusiec, W. Klauzula Sumienia dla Farmaceutów: Analgia Opinii Wydanej Przez Comitato Nazionale pre la Bioethica. Diametros (2012) 32:62–76. doi:10.13153/diam.32.2012.477

9. Orzeszyna, K. Klauzula Sumienia Jako Gwarancja Realizacji Prawa Do Wolności Sumienia. Medyczna Wokanda (2017) 9:17–29.

10. Chavkin, W, Leitman, L, and Polin, K. Global Doctors for Choice. Conscientious Objection and Refusal to Provide Reproductive Healthcare: A White Paper Examining Prevalence, Health Consequences, and Policy Responses. Int J Gynecol Obstet (2013) 123(3):41–56. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(13)60002-8

11. Shanawani, H. The Challenges of Conscientious Objection in Health Care. J Religion Health (2016) 55(2):384–93. doi:10.1007/s10943-016-0200-4

12. USTAWA. Ustawa O Zawodach Lekarza I Lekarza Dentysty (1996). Available From: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19970280152/U/D19970152Lj.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

13. USTAWA. Ustawa O Zawodach Pielęgniarki I Położnej (2011). Available From: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20111741039/U/D20111039Lj.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

14. Kodeks etyki lekarskiej. Kodeks Etyki Lekarskiej (2004). Available From: https://nil.org.pl/uploaded_images/1574857770_kodeks-etyki-lekarskiej.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

15. Czekajewska, J. Ethical Aspects of the Conscience Clause in Polish Medical Law. Kultura i Edukacja (2018) 4(122):206–20. doi:10.15804/kie.2018.04.13

16. Półtawska, W. Declaration of Faith of Catholic Doctors and Students of Medicine, on the Sexuality and Fertility of Human Beings. Linacre Q (2015) 82(2):99–100. doi:10.1179/0024363914Z.000000000111

17. Olszówka, M. Analgia Projektu Ustawy O Zmianie Ustawy O Zawodach Lekarza I Lekarza Dentysty, Ustawy O Diagnostyce Laboratoryjnej Oraz Ustawy O Zawodach Pielęgniarki I Położnej, Zawartego W Druku Senackim Nr 1034/IX Kadencja (Sprzeciw Sumienia). Studia z Prawa Wyznaniowego (2019) 22:349–77. doi:10.31743/spw.4788

18. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Klauzula Sumienia Lekarza I Farmaceuty (2014). Available From: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2014/K_094_14.PDF (Accessed August 9, 2023).

19. Pellegrino, ED. The Physician's Conscience, Conscience Clauses, and Religious Belief: A Catholic Perspective. Fordham Urban L J (2002) 30(1):221–44.

20. Strickland, SL. Conscientious Objection in Medical Students: A Questionnaire Survey. J Med Ethics (2012) 38(1):22–5. doi:10.1136/jme.2011.042770

21. Nordstrand, SJ, Nordstrand, MA, Nortvedt, P, and Magelssen, M. Medical Students’ Attitudes Towards Conscientious Objection: A Survey. J Med Ethics (2014) 40(9):609–12. doi:10.1136/medethics-2013-101482

22. Soengas, AM, and Ramos, AC. Percepción del Alumnado de Medicina Sobre la Objeción de Conciencia a la Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo en Galicia. Gaceta Sanitaria (2019) 34(2):150–6. doi:10.1016/j.gaceta.2019.02.007

23. Bouthillier, ME, and Opatrny, L. A Qualitative Study of Physicians’ Conscientious Objections to Medical Aid in Dying. Palliat Med (2019) 33(9):1212–20. doi:10.1177/0269216319861921

24. Zaręba, K, La Rosa, VL, Kołb-Sielecka, E, Ciebiera, M, Ragusa, R, Gierus, J, et al. Attitudes and Opinions of Young Gynecologists on Pregnancy Termination: Results of a Cross-Sectional Survey in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(11):3895. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113895

25. Autorino, T, Mattioli, F, and Mencarini, L. The Impact of Gynecologists’ Conscientious Objection on Abortion Access. Soc Sci Res (2020) 87:102403. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102403

26. USTAWA. Ustawa O Planowaniu Rodziny, Ochronie Płodu Ludzkiego I Warunkach Dopuszczalności Przerywania Ciąży (1993). Available From: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19930170078/U/D19930078Lj.pdf (Accessed August 9, 2023).

27. Makowska, M, Boguszewski, R, and Sacharczuk, K. A Study of Opinions About the Polish Constitutional Tribunal’s Judgement Strengthening Polish Abortion Laws. Eur J Contraception Reprod Health Care (2021) 27(1):39–44. doi:10.1080/13625187.2021.1980872

28. Boratyńska, M. O Łamaniu Przepisów Dopuszczających Przerywanie Ciąży. Prawo i Medycyna (2008) 10(2):88–103.

29. Nawrot, O. Prawa Człowieka, Sprzeciw Sumienia I Państwo Prawa. In: P Stanisz, J Pawlikowski, and M Ordon, editors. Sprzeciw Sumienia W Praktyce Medycznej – Aspekty Etyczne I Prawne. Lublin: KUL (2014). p. 105–16.

30. Bosek, L. Problem Zakresowej Niekonstytucjonalności Art. 39 Ustawy O Zawodach Lekarza I Lekarza Dentysty. In: P Stanisz, J Pawlikowski, and M Ordon, editors. Sprzeciw Sumienia W Praktyce Medycznej – Aspekty Etyczne I Prawne. Lublin: KUL (2014). p. 87–104.

31. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Religijność Polaków W Ostatnich 20 Latach (2020). Available From: https://cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2020/K_063_20.PDF (Accessed August 9, 2023).

32. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Źródła Zasad Moralnych (2022). Available From: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2022/K_001_22.PDF (Accessed August 9, 2023).

33. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Zasady Moralne a Religia (2017). Available From: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2017/K_004_17.PDF (Accessed August 9, 2023).

34. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. Stosunek Polaków Do Wybranych Zjawisk I Zachowań Kontrowersyjnych Moralnie (2021). Available From: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2021/K_165_21.PDF (Accessed August 9, 2023).

35. Grzymata-Busse, A, Nations Under God: How Churches Use Moral Authority to Influence Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2015). doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0sfx

36. Calkin, S, and Kaminska, ME. Persistence and Change in Morality Policy: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Politics of Abortion in Ireland and Poland. Feminist Rev (2020) 124:86–102. doi:10.1177/0141778919894451

37. Pawlikowski, J, Sak, JJ, and Marczewski, K. Physicians’ Religiosity and Attitudes Towards Patients. Ann Agric Environ Med (2012) 19(3):503–7.

38. Lankau, A, Krajewska-Kułak, E, Jankowiak, B, Baranowska, A, and Bejda, G. Effect of Nurses’ Religious Beliefs on Their Empathy and Life Satisfaction. Prog Health Sci (2017) 7(2):18–25. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0010.5717

39. Wenger, NS. Physicians' Religiosity and End-Of-Life Care Attitudes and Behaviors. Mount Sinai J Med (2004) 71(5):335–43.

40. Balslev van Randwijk, C, Opsahl, T, Assing Hvidt, E, Bjerrum, L, Kørup, AK, and Hvidt, NC. Association Between Danish Physicians’ Religiosity and Spirituality and Their Attitudes Toward End-Of-Life Procedures. J Religion Health (2020) 59(5):2654–63. doi:10.1007/s10943-020-01026-3

41. Emanuel, EJ, Fairclough, D, Clarridge, BC, Blum, D, Bruera, E, Penley, WC, et al. Attitudes and Practices of U.S. Oncologists Regarding Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide. Ann Intern Med (2000) 133(7):527–32. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-133-7-200010030-00011

42. Brown, J, Goodridge, D, Thorpe, L, and Crizzle, A. What Is Right for Me, Is Not Necessarily Right for You: The Endogenous Factors Influencing Nonparticipation in Medical Assistance in Dying. Qual Health Res (2021) 31(10):1786–800. doi:10.1177/10497323211008843

43. Awoonor-Williams, JK, Baffoe, P, Aboba, M, Ayivor, P, Nartey, H, Felker, B, et al. Exploring Conscientious Objection to Abortion Among Health Providers in Ghana. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health (2020) 46:51–9. doi:10.1363/46e8920

44. Davidson, L, Pettis, C, Joiner, A, Cook, D, and Klugman, C. Religion and Conscientious Objection: A Survey of Pharmacists’ Willingness to Dispense Medications. Soc Sci Med (2010) 71(1):161–5. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.027

45. Davis, S, Schrader, V, and Belcheir, M. Influencers of Ethical Beliefs and the Impact on Moral Distress and Conscientious Objection. Nurs Ethics (2012) 19(6):738–49. doi:10.1177/0969733011423409

46. Domaradzki, J, and Walkowiak, D. Does Religion Influence the Motivations of Future Healthcare Professionals to Volunteer During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland? An Exploratory Study. J Religion Health (2021) 60:1507–20. doi:10.1007/s10943-021-01231-8

47. Kobyliński, A. Aspekty Etyczno-Prawne Sporu O Klauzulę Sumienia We Włoszech W Latach 2014-2015. Studia Ecologiae et Bioethicae (2015) 13(3):25–48. doi:10.21697/seb.2015.13.3.02

48. Ambrus, T, Kolář, J, and Krempaská, R. Výhrada Svědomí Při Výkonu Profese Lékárníka Ve Slovenské Republice. Ceska a Slovenska Farmaciei (2016) 65(5):176–81.

49. Baranowska, J, Baranowski, S, Kuchta, J, and Liwińska, Z. Stanowisko Farmaceutów I Studentów Farmacji Wobec Klauzuli Sumienia. Pielęgniarstwo Polskie (2012) 4(46):187–9.

50. Lamb, C, Babenko-Mould, Y, Evans, M, Wong, CA, and Kirkwood, KW. Conscientious Objection and Nurses: Results of an Interpretive Phenomenological Study. Nurs Ethics (2019) 26(5):1337–49. doi:10.1177/0969733018763996

51. Lamb, C, Evans, M, Babenko-Mould, Y, Wong, CA, and Kirkwood, KW. Nurses' Use of Conscientious Objection and the Implications for Conscience. J Adv Nurs (2019) 75(3):594–602. doi:10.1111/jan.13869

52. Piecuch, A, Gryka, M, and Kozłowska-Wojciechowska, M. Attitudes Towards Conscientious Objection Among Community Pharmacists in Poland. Int J Clin Pharm (2014) 36(2):310–5. doi:10.1007/s11096-013-9878-5

53. Toro-Flores, R, Bravo-Agüi, P, Catalán-Gómez, MV, González-Hernando, M, Guijarro-Cenisergue, MJ, Moreno-Vázquez, M, et al. Opinions of Nurses Regarding Conscientious Objection. Nurs Ethics (2019) 26(4):1027–38. doi:10.1177/0969733017731915

54. Chavkin, W, Swerdlow, L, and Fifield, J. Regulation of Conscientious Objection to Abortion: An International Comparative Multiple-Case Study. Health Hum Rights (2017) 19(1):55–68.

55. Shaw, J, and Downie, J. Welcome to the Wild, Wild North: Conscientious Objection Policies Governing Canada's Medical, Nursing, Pharmacy, and Dental Professions. Bioethics (2014) 28(1):33–46. doi:10.1111/bioe.12057

56. Balmer, L. Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Conscientious Objectors. Lancet (2006) 367(9527):1980. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68884-3

57. Deans, Z. Conscientious Objections in Pharmacy Practice in Great Britain. Bioethics (2013) 27(1):48–57. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01918.x

58. Merks, P, Szczęśniak, K, Świeczkowski, D, Blicharska, E, Paluch, A, Olszewska, A, et al. Klauzula Sumienia Dla Farmaceutów W Środowisku Farmaceutów Praktykujących W Polsce I Wielkiej Brytanii. Farmacja Polska (2015) 71(8):2–9.

59. Christopher, C. Conscientious Objection and Healthcare in the UK: Why Tribunals Are Not the Answer. J Med Ethics (2016) 42(2):69–72. doi:10.1136/medethics-2015-102692

60. Cooper, RJ, Wingfield, J, and Bissell, P. Ethical, Religious and Factual Beliefs About the Supply of Emergency Hormonal Contraception by UK Community Pharmacists. BMJ Sex Reprod Health (2008) 34(1):47–50. doi:10.1783/147118908783332122

61. Maxwell, C, McKendrick, J, Hanlon, C, Penson, P, and Fleming, V. Exploring Pharmacists’ Views Surrounding Conscientious Objection to Abortion and Implications in Practice. Int J Pharm Pract (2021) 29(3):258–64. doi:10.1093/ijpp/riab009

62. Voultsos, P, Zymvragou, CE, and Raikos, N. Perceptions and Experiences of Female Nurses When Confronted With Expressing a Conscientious Objection Towards End-of-Life Care in Greece. BMC Nurs (2023) 22:372. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01555-8

63. Fleming, V, Frith, L, Luyben, A, and Ramsayer, B. Conscientious Objection to Participation in Abortion by Midwives and Nurses: A Systematic Review of Reasons. BMC Med Ethics (2018) 19(1):31. doi:10.1186/s12910-018-0268-3

Keywords: conscience clause, healthcare professionals, nurses, pharmacists, physicians, religion

Citation: Czekajewska J, Walkowiak D and Domaradzki J (2023) The Association Between Religion and Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes Towards the Conscience Clause. A Preliminary Study From Poland. Int J Public Health 68:1606526. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1606526

Received: 18 August 2023; Accepted: 20 November 2023;

Published: 01 December 2023.

Edited by:

Calogero Guccio, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Aleksandar Višnjić, University of Niš, SerbiaOne reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Copyright © 2023 Czekajewska, Walkowiak and Domaradzki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Justyna Czekajewska, anVzdHluYWN6ZWthamV3c2thQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Justyna Czekajewska, orcid.org/0000-0003-2833-8815; Dariusz Walkowiak, orcid.org/0000-0001-8874-2401; Jan Domaradzki, orcid.org/0000-0002-9710-832X

Justyna Czekajewska

Justyna Czekajewska Dariusz Walkowiak

Dariusz Walkowiak Jan Domaradzki

Jan Domaradzki