- 1Centre for Geographic Medicine Research Coast, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Kilifi, Kenya

- 2School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 3Institute for Human Development, Aga Khan University, Nairobi, Kenya

- 4MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt), Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 5Department of Psychiatry, Warneford Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 6Department of Public Health, Pwani University, Kilifi, Kenya

Objectives: This study explores the perceptions of adults living with HIV aged ≥50 years (recognized as older adults living with HIV—OALWH), primary caregivers and healthcare providers on the health challenges of ageing with HIV at Kilifi, a low literacy setting on the coast of Kenya.

Methods: We utilized the biopsychosocial model to explore views from 34 OALWH and 22 stakeholders on the physical, mental, and psychosocial health challenges of ageing with HIV in Kilifi in 2019. Data were drawn from semi-structured in-depth interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed. A framework approach was used to synthesize the data.

Results: Symptoms of common mental disorders, comorbidities, somatic symptoms, financial difficulties, stigma, and discrimination were viewed as common. There was also an overlap of perceived risk factors across the physical, mental, and psychosocial health domains, including family conflicts and poverty.

Conclusion: OALWH at the Kenyan coast are perceived to be at risk of multiple physical, mental, and psychosocial challenges. Future research should quantify the burden of these challenges and examine the resources available to these adults.

Introduction

The last decade has witnessed a dramatic shift in the demographic profile of people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) globally. Presently, many HIV clinics are caring for a growing number of adults aged ≥50 years (categorized as older adults) due to increased survival in people living with HIV (PLWH) and a steady rise in HIV diagnoses in this age cohort [1]. More than 30% of the PLWH in High-Income Countries (HICs) are now aged ≥50 years [1] compared to 15% in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [2]. These statistics herald a new era in the HIV epidemic response, where the needs and demands of the OALWH can no longer be ignored, especially in Eastern and Southern Africa, home to more than half the number of OALWH globally [1].

Research findings, mainly from HICs, indicate that OALWH present with an average of three comorbid conditions in addition to HIV, including medical diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance use, cognitive problems) and social challenges (e.g., stigma, loneliness, and lack of social support) [3–6]. The observed mental health challenges reduce the quality of life of these adults and have important health implications, e.g., poor HIV treatment [7]. The physical health problems faced by OALWH may also be complicated by environmental and psychosocial challenges such as poverty, food insecurity and lack of support [7].

Despite the evidence of complex health challenges related to ageing and HIV, little research has qualitatively examined how OALWH understand their health and care needs. To date, most studies of ageing and HIV in SSA are cross-sectional studies focusing on biomedical processes and outcomes and rarely provide local insight into the health and wellbeing of these adults [8]. Qualitative studies are needed to better understand the experiences and needs of this diverse population, especially among low-literacy populations. This is especially important as many cohorts of OALWH are emerging for the first time across the SSA region, and the apparent variability in findings among previous studies, e.g., in the prevalence and determinants of chronic comorbidities [8]. Apart from complementing quantitative studies in accurately documenting the burden and determinants of the health challenges in these adults, qualitative studies will shed light on the contextual factors to guide the development or adaptation and subsequent implementation of culturally appropriate interventions in this population. Overall, the few qualitative studies among OALWH in SSA are mainly concentrated in Uganda [9–13] and South Africa [14–18]. Others are from Kenya, Eswatini and Malawi [19–22]. In Uganda, ageing with HIV is seen as a daily challenge financially and socially [9–13]. The key barriers to successful ageing with HIV in this setting include stigma, food insecurity, and unmet healthcare needs, particularly for associated comorbidities such as common mental disorders. In South Africa, the crucial barriers to living with HIV in old age include food insecurity, unemployment, stigma, and access to transportation and healthcare [14–18].

Emerging data suggest that OALWH in Kenya face complex challenges when seeking care, including visits to multiple providers to manage HIV and comorbidities, ageist discrimination, and inadequate social support [20, 21]. However, these data come from the Western region of Kenya. As such, the health and wellbeing experiences of OALWH from other parts of the country is not known. To bridge this research gap, we conducted in-depth interviews to explore the health challenges faced by OALWH at Kilifi, a low literacy setting at the coast of Kenya. Using the biopsychosocial framework, we explore the perceptions of 34 OALWH, 11 healthcare providers and 11 primary caregivers on the physical, mental, and psychosocial challenges of ageing with HIV in this setting.

Theoretical Framework

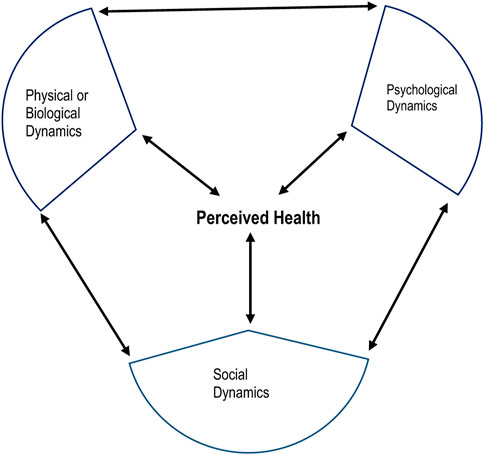

We utilized Engel’s biopsychosocial model of health [23], which provides a logical account of the chronic, complex, and dynamic nature of HIV. This model recognizes healthy ageing as the ability to thrive in an evolving environment influenced by physical/biological, mental/psychological, and social factors (Figure 1). The model provides a holistic approach to understanding the health needs of older adults and is supported by calls for research that positively impact the physical, mental, and social aspects of ageing with HIV [24–26]. According to this model, the cause, manifestation and outcome of wellness and disease are determined by a dynamic interaction between physical, psychological, and social factors [23]. Each model component includes systems that reciprocally influence other dynamics in the model and also affect health.

FIGURE 1. Components of the biopsychosocial model of health (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

Methods

Study Context and Participants

This study was conducted in 2019 at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) located within Kilifi County on the coast of Kenya. By the end of 2019, there were roughly 1.5 million residents in Kilifi County, the majority of whom were rural dwellers (∼60%), and 11% were aged ≥50 years [27]. Kilifi has an HIV prevalence of 38 per 1,000 people [28] in the general population and is currently unknown in those aged ≥50 years. People living with HIV usually receive care in specialized HIV clinics within primary care facilities.

This study involved the following three groups of participants.

a) OALWH aged ≥50 years receiving HIV care and treatment at the HIV Comprehensive Care Clinic of the Kilifi County Hospital (KCH).

b) Healthcare providers attending to OALWH.

c) Primary caregivers of OALWH.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Study participants were selected purposively to represent diversity in the participants’ characteristics, including age, sex, and the cadre of service (for healthcare providers). Initial contact was made via a community health volunteer stationed at the KCH. Recruitment was conducted by a trained research assistant in liaison with the community health volunteer during their routine clinic visits. OALWH had to be ≥50 years old and on HIV treatment to be eligible. Primary caregivers were identified through the OALWH, usually during their scheduled clinic visits. These caregivers had to be directly involved in providing care and support, e.g., medical care to an OALWH. HIV providers were approached at their place of work and invited to participate. We specifically targeted providers who provided direct care to OALWH. Participants who agreed to participate were invited to a face-to-face interview at a convenient place, usually at KEMRI Kilifi.

Data Collection and Tools

The lead author (PM) conducted in-depth interviews lasting, on average 45–60 min with each participant. All the interviews were guided by a pre-tested semi-structured interview schedule developed with guidance from prior work on HIV and ageing. All interviews were conducted in Swahili, English or Giryama. We also sought permission from the participants to take notes and audio record the interviews.

Among OALWH, topic guide themes included: patient illness experiences following diagnoses. These issues were explored using general open-ended questions, followed by additional probing to highlight further the issue raised. For healthcare providers, participants were invited to share their experiences providing care to OALWH. Among caregivers, we explored different issues, including their experiences taking care of OALWH and the challenges these adults faced in their environment. We also collected respondents’ demographic information such as age, sex, educational status, and employment status. For OALWH, we also collected HIV-related information. All participants were given Ksh 350 (about US$3) as compensation for time spent in the research, with transport expenses also reimbursed.

Data Analysis

All the audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by a team of four trained research assistants. Subsequent data management was done using NVivo software (version 11). We applied the framework approach to analyze our qualitative data [29]. Initially, two authors (PM and AA) developed a preliminary coding framework inductively through in-depth reading of transcripts and deductively by considering themes from the interview schedules. These codes were discussed, and consensus reached on how they should be brought together into themes with guidance from the biopsychosocial model. The initial coding framework was progressively expanded to capture emergent themes as coding continued. When the coding was complete in NVivo, the lead author grouped all themes related to a specific concept to form categories and exported this to a word-text processor to produce charts. The generated charts were used to summarize data, look for similarities or differences and explore patterns among the three groups of participants in the analyzed data.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The study also obtained ethical clearance from the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (KEMRI/SERU/CGMR-C/152/3804) and the Kilifi County Department of Health Services (HP/KCHS/VOL.X/171).

Results

Sample Characteristics

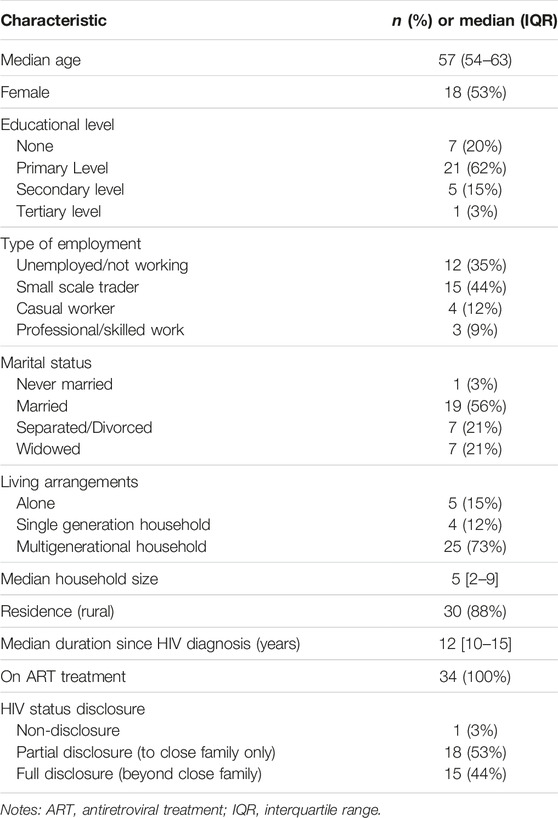

We interviewed a total of 56 participants (34 OALWH, 11 healthcare providers and 11 primary caregivers) in this study. Among OALWH, 53% were women; most (82%) had up to a primary level of education, and their age ranged from 50 to 72 years. All the OALWH were on HIV treatment. Healthcare providers included six registered nurses, two clinical officers, two project managers of community-based organizations and one HIV counsellor. All the primary caregivers were family members, most of whom (73%) were female. Further sociodemographic information and HIV-related characteristics of the OALWH are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of older adults living with HIV (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

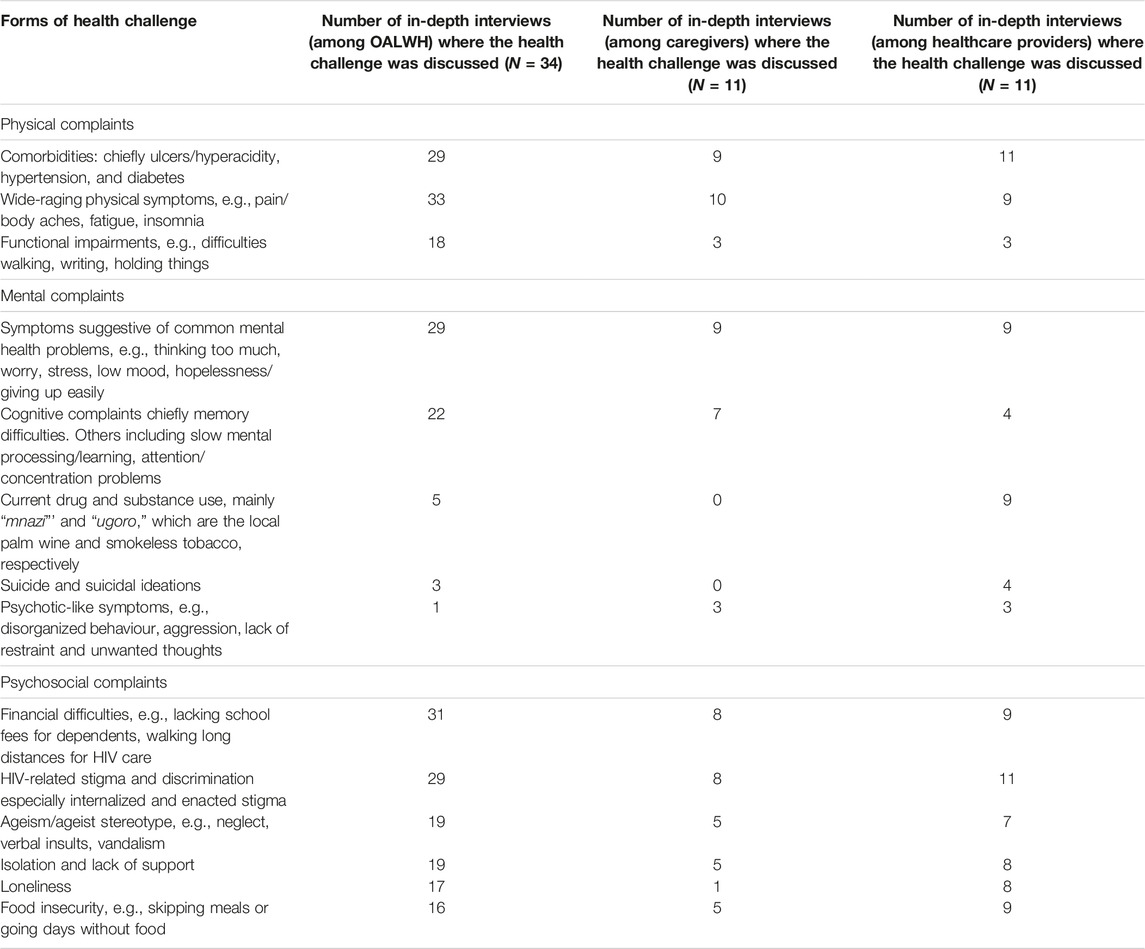

Perceived Biopsychosocial Challenges Confronted by OALWH

The different forms of biopsychosocial challenges faced by OALWH are summarized in Table 2. Overall, most of the OALWH shared their 10-plus years of experience living with HIV, from the time of diagnosis to their current state. The majority of the OALWH described moving from a state of shock, fear, anger, denial, hopelessness, or suicidal ideation upon diagnosis to a state of acceptance and ownership. This transition was not without challenges, as many of the OALWH noted going through traumatic experiences from family members, friends, workmates, and healthcare providers. Thereafter, they narrated moving from a state of ownership to a state of constant survival characterized by an array of health problems which we have conceptualized as physical (biological), mental (psychological) and social in the following sections according to the biopsychosocial model.

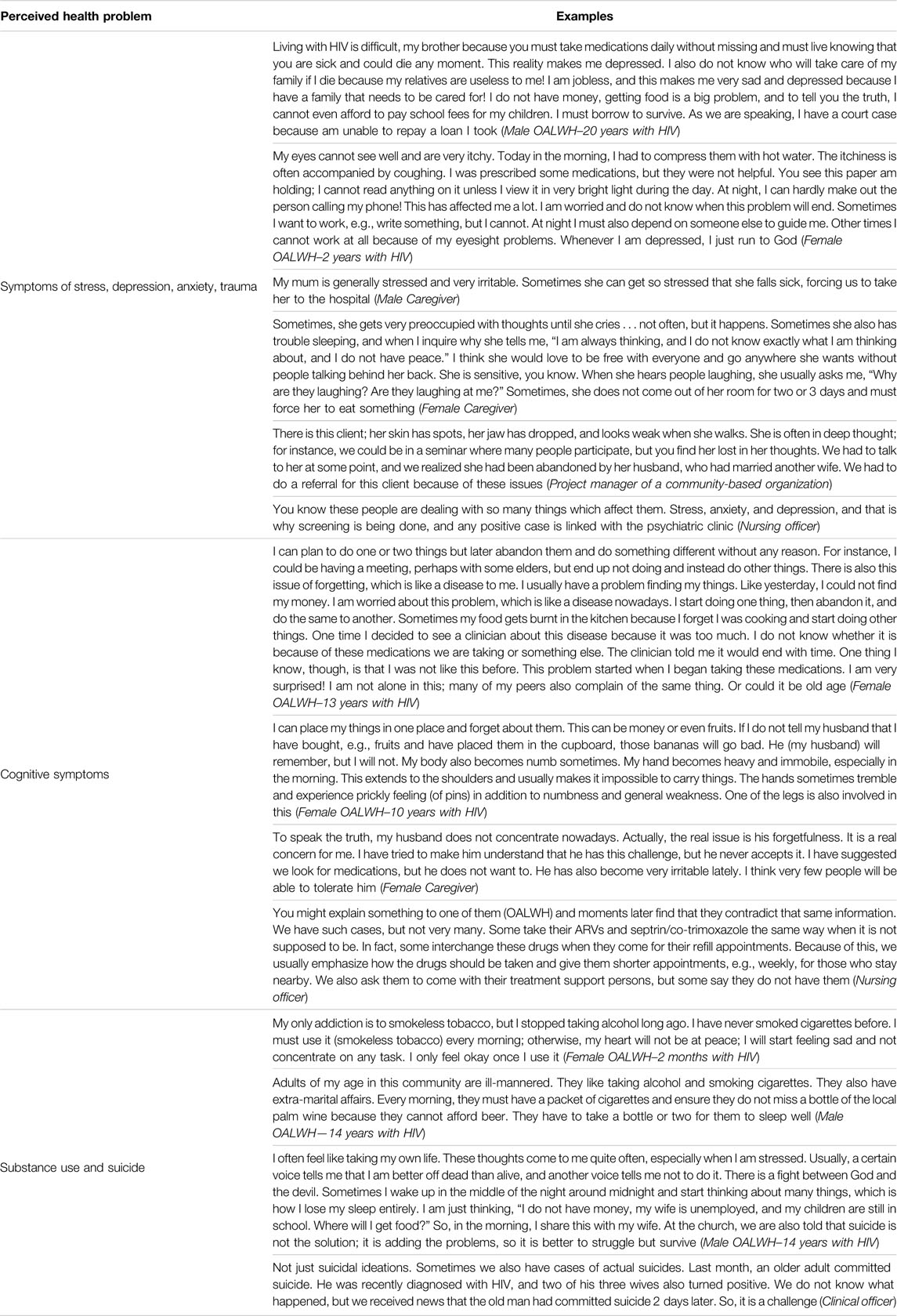

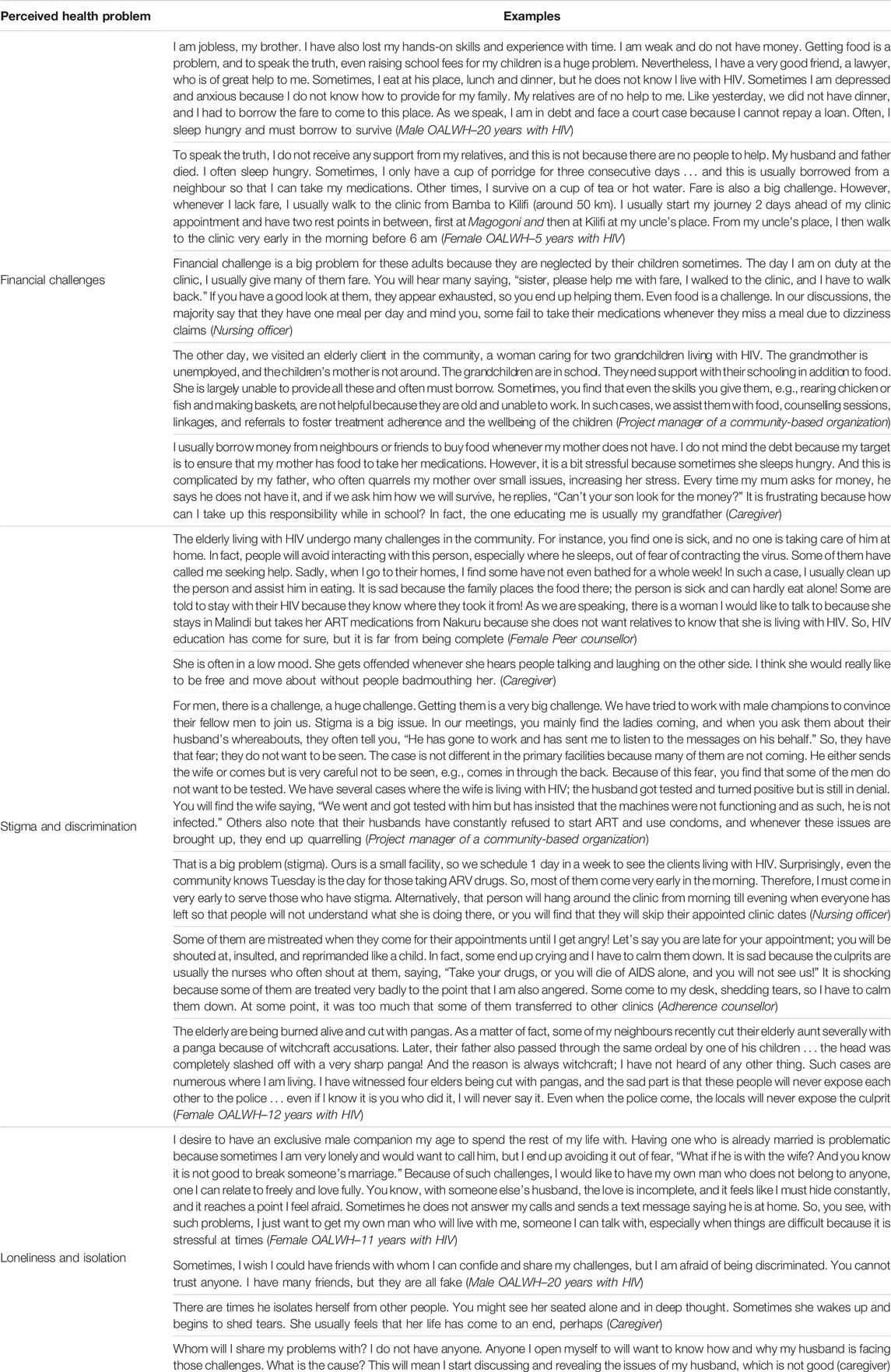

TABLE 2. Perceived forms of physical, mental, and psychosocial health challenges facing older adults living with HIV as discussed by study participants (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

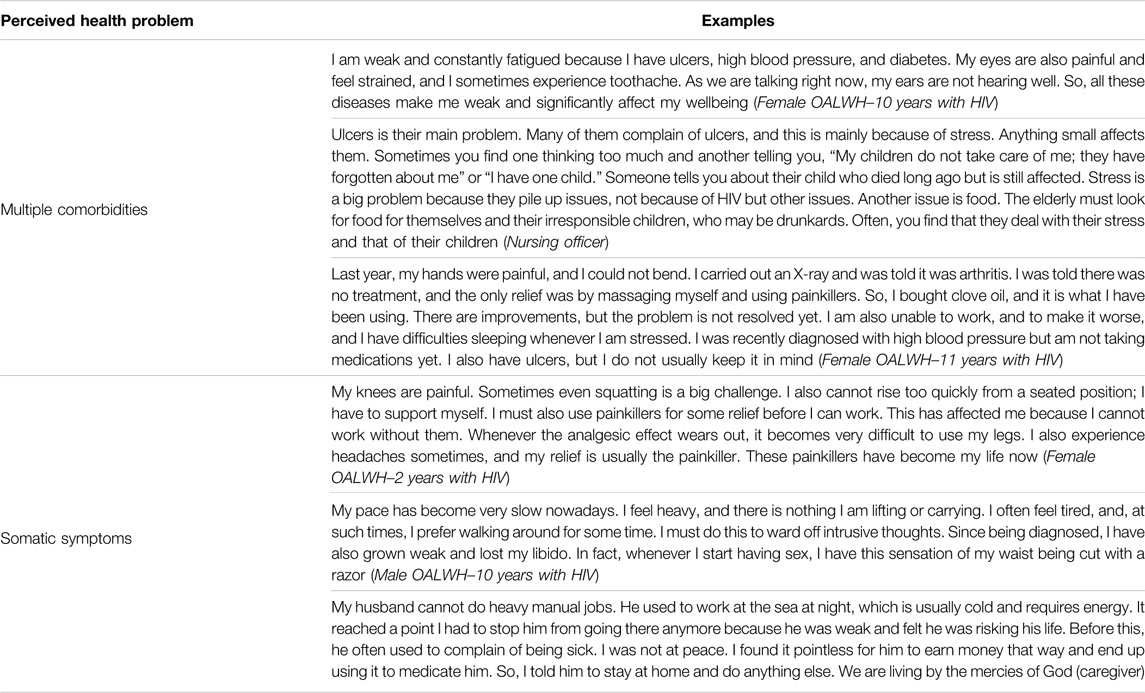

Perceived Physical Health Challenges

Physical complaints were commonly described by several participants. Key among these concerns was the onset of multiple comorbidities in these adults, which was frequently associated with pain, loss of control of one’s body, emotional distress, and increased treatment burden. Hypertension, diabetes, ulcers/hyperacidity, hearing, and visual impairments were the most frequently reported comorbidities across the participants. Other conditions discussed (though to a lesser extent) included obesity, arthritis, stroke, teeth problems, cervical cancer, TB, and pneumonia. Apart from these comorbidities, somatic symptoms were also discussed in several interviews across the groups. Body pain, headaches, insomnia, fatigue or low energy, and limb numbness were also frequently reported. Some participants believed that the onset of the physical challenges was because of HIV-related factors (e.g., HIV infection itself, long-term ART), multimorbidity, old age, food insecurity, emotional distress, substance use, and the nature of someone’s work. Participant quotes are given in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Participants’ physical health challenges quotes (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

Perceived Mental Health Challenges

We have discussed these issues under the following headings: symptoms suggestive of common mental health problems, cognitive symptoms, substance use problems, and others (suicidal ideation and psychotic symptoms). Participant quotes are given in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Participants’ mental health quotes (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

Symptoms Suggestive of Common Mental Health Problems

Emotional and behavioral symptoms, suggestive of anxiety and depression, were described to be prevalent across the participant groups. Key among these symptoms included thinking too much, persistent stress, low mood, anger/irritability, worrying a lot, hopelessness, restlessness, panic attacks, and nightmares. Other prominent symptoms included insomnia, self-isolation, low self-esteem, headaches, and low libido. Overall, these symptoms were described to be on-and-off among the OALWH and were frequently associated with the exacerbation of physical conditions, chronic use of drugs, financial instability, and overall poor quality of life. For many participants, the onset and persistence of physical body changes (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, obesity, body weakness) were considered a significant risk for mental complaints.

Cognitive/Neurological Challenges

The commonly reported complaint in this category was memory difficulty, e.g., difficulties recalling important dates or finding items. Surprisingly, most OALWH reported that they rarely forgot to take their medications. Many healthcare providers corroborated this, although they also noted that there are some OALWH at risk of poor adherence caused by cognitive impairments. Other cognitive symptoms included attention/concentration, processing/learning, movement, and multi-tasking difficulties. Peripheral neuropathy was also reported to be a common neurological problem in these adults and was associated with significant distress. Among OALWH, the cognitive symptoms were viewed as an additional disease, and many did not understand its causes. The few who sought medical attention ended up being disappointed, sometimes being advised that it will resolve on its own or there is medicine, but it is costly.

Drugs and Substance use Problems

Current drug and substance use was mainly discussed by healthcare providers. In contrast, most OALWH reported having a history of drug and substance use, especially alcohol and tobacco but stopped following HIV diagnosis. However, some confessed to being social drinkers. “Mnazi” and “ugoro” (smokeless tobacco or snuff) were the commonly used substances. Many providers emphasized that mnazi drinking is a big problem, noting that some OALWH came for their routine clinic appointments while drunk and sometimes forgot to take their ART drugs. Some providers also associated the mnazi drinking problem with unsuppressed viral loads, treatment default, and sexual risk-taking behaviors, e.g., multiple partners. The key underlying factors for the increased use of mnazi included family conflicts which often led to stress, unstable sexual partners, negative coping skills, culture, and easy access to these substances. Ugoro, the other commonly abused substance, was especially common among women. Beer, cigarettes, khat and marijuana were also discussed, although to a lesser extent.

Suicidal Ideation and Psychotic-like Symptoms

Three OALWH reported having intermittent suicidal ideations. This was corroborated by the healthcare providers. The commonly associated factors included persistent stress (caused mainly by financial difficulties and family conflicts), evil spirits, and HIV-related (e.g., getting tired of taking ART and not getting healed). Though limited, there were also few reports of psychotic-like symptoms (e.g., disorganized behaviour, aggression, lack of restraint and unwanted thoughts) across the three groups of participants. These cases were frequently observed around the time of HIV diagnosis.

Perceived Psychosocial Challenges

We present these issues under the following categories: a) financial challenges, b) stigma and discrimination, and c) loneliness and isolation. Participant quotes are given in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Participants’ psychosocial challenges quotes (HIV-Associated Neurobehavioral Disorders Study, Kilifi County, Kenya 2019).

Financial Challenges

This was discussed in virtually all the interviews we conducted. Many participants felt that financial difficulty was the most crucial issue affecting OALWH in the study setting because of its massive impact on food security, caregiving responsibilities, emotional wellbeing, and management of HIV and other comorbidities. Many OALWH reported skipping meals or going hungry for some days, lacking school fees for their dependents, and walking long distances to access HIV care for lack of money. This was corroborated by the healthcare providers and caregivers, who further stated that many of those who slept hungry tended to skip their medications, complaining of dizziness, headaches, and stomach discomfort. To some extent, this was associated with poor treatment outcomes, including unsuppressed viral load and poor retention in care.

Stigma and Discrimination

This theme incorporates HIV-related stigma and ageism (discrimination based on age). Despite relatively high levels of disclosure, many OALWH experienced HIV-related stigma. Discriminatory behaviour (enacted stigma from malicious gossip to outright discrimination, e.g., neglect, isolation, verbal insults) was reported to be common, especially in the most rural areas of the study setting. The perpetrators were mainly family members. Stigma was also reported to be common in mnazi drinking dens called “mangwe,” burial ceremonies, and HIV clinics. Internalized stigma emerged as an important theme, especially among the OALWH and was frequently associated with self-isolation, anxiety or high consciousness of self, fear of seeking assistance, attending very far HIV clinics, stress, and irritability.

Many participants also highlighted discrimination based on age, which was perceived in multiple settings, including the home (mainly through isolation, neglect, and lack of respect from children), HIV clinic (e.g., scolded openly and verbal insults), and the community level. It also emerged that some community members around the study setting (especially in the most rural areas) regarded older people suspiciously. Many participants narrated hearing or witnessing several older people being beaten, beheaded, or burned alive in their houses for suspected witchcraft, and the perpetrators were mainly close family members.

Loneliness and Isolation

This emerged as an important theme in the conversations with OALWH and healthcare providers. Despite living in multigenerational households, many of the OALWH expressed loneliness and isolation. Some had lost their partners, some their closest relatives and others saw their circle of friends getting smaller. Still, others felt neglected by those around them.

Discussion

Summary of Key Findings

We conducted this study to gain a preliminary understanding of the health challenges facing OALWH on the coast of Kenya. Our study provides insight into the complex challenges of ageing with HIV and opens up opportunities for further epidemiologic research and subsequent development of tailored interventions for OALWH. Overall, our findings reveal that OALWH in this setting are particularly vulnerable to mental health problems, especially symptoms suggestive of common mental conditions. They are also at risk of physical health challenges, including comorbidities and somatic complaints. Mental and physical health impairments are complicated by psychosocial challenges, including poverty, lack of support, stigma, and discrimination. Noteworthily, there was an overlap of perceived risk factors across the three health domains (e.g., family conflicts, poverty, food insecurity), suggesting that OALWH who experience these shared cumulative risk factors are more likely to face multiple health challenges. It also implies that the action taken to mitigate any or some of the shared enabling factors is likely to have a preventive spillover effect across multiple health domains. Most of the views of OALWH on health challenges were corroborated by views from the providers and caregivers. However, a few disparities emerged in some of the perceived health challenges. Current drug and substance use, for instance, was reported mainly by healthcare providers, while cognitive complaints were discussed by OALWH.

Physical Health Challenges

Our discussions clearly showed that physical challenges are important concerns for older adults living with HIV on the coast of Kenya, given their negative impacts on other health domains and overall health. As the number of OALWH increases in many HIV clinics, HIV care will increasingly need to draw on a wide range of medical disciplines besides evidence-based screening and monitoring protocols [30]. Unfortunately, most healthcare providers presently lack guidance and training to identify and manage declines in physical and mental capacities in this population. The siloed provision of HIV care and other comorbidities could also imply that providers are unaware of the patients’ other conditions. Our findings are similar to those reported in a recent qualitative exploration of challenges seeking HIV care services for OALWH [20]. Integration of services for HIV and non-communicable diseases in primary care may enable settings like Kenya to expand healthcare coverage for PLWH.

The current findings also revealed a prominent intersection between ageing and HIV. For most participants, ageing rather than HIV was the primary concern. This is not surprising considering that among PLWH with controlled viraemia, HIV infection often stops being the overriding comorbidity but is simply a key element in the overall milieu of multiple conditions [31, 32]. In a few instances, however, participants discussed that their experiences were associated with HIV, long-term medication use, or side effects, although their providers attributed these conditions to normal ageing. They advised the OALWH to “wait,” and they will improve with time. Disagreements about the cause of a symptom or health condition may contribute to doubts about the effectiveness of treatment or conceal an emerging disease and contribute to delayed diagnoses such as medication side effects and polypharmacy.

Mental Health Challenges

Our finding of substantial symptoms suggestive of common mental health conditions among OALWH is consistent with previous reports of poor mental health among PLWH in the study setting, albeit among younger populations [33, 34]. However, our study does not establish whether the burden among OALWH is higher or lower than that observed among young PLWH. Quantitative studies are needed to confirm this comparison. Nonetheless, OALWH may be facing a higher burden of common mental problems than their younger counterparts for different reasons. Firstly, many of the longest surviving OALWH may be significantly impacted by the legacy of the early years of the epidemic, including multiple bereavements and “survivor guilt” [35]. Secondly, the higher burden may also be attributed to the numerous challenges that OALWH face, e.g., poverty, food insecurity, caregiving responsibility, double stigma, and the onset of physical body changes, as evidenced in our study.

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, the manifestations of cognitive and neurological problems have been ubiquitous and frequently associated with poor treatment outcomes and impairment of activities of daily living [7]. In our study, the most frequently reported cognitive problem—memory difficulty—was commonly associated with stress and shame. Strikingly, healthcare providers seldom suspected cognitive impairments among OALWH and screenings were never done. This observation is similar to what has been reported in South Africa [32, 36]. Despite the reported memory challenges in this study, OALWH rarely forgot to take their medications (from their own self-reports and that of their providers). This finding is not unique in the HIV literature [37]. It is possible that OALWH are more organized and experienced and possibly more motivated after experiencing the initial devastating outcomes of the HIV pandemic. However, it is still essential to monitor the cognitive function of these adults to prevent treatment non-adherence, considering the multiple challenges they face, which are likely to impact their cognitive function and worsen as they grow older.

Our findings also noted a section of OALWH at risk of substance use dependence, especially home-brewed alcohol, called mnazi. This is not surprising given that the consumption of mnazi is common among the inhabitants of Kilifi because it is cheap and often less regulated [38]. The need to address this problem is even more crucial since it was associated with rising cases of sexual risk-taking behaviour and poor treatment outcomes in this cohort.

Psychosocial Challenges

Psychosocial factors are well-known predictors of treatment adherence, disease progression and quality of life for PLWH [39]. Findings from our exploratory study suggest that financial difficulties, loneliness, stigma, and discrimination are prevalent among OALWH in the study setting and are associated with mental complaints and physical health problems. Similar findings have been reported in Western Kenya among OALWH [20]. These findings are not surprising, given the country’s prevailing situation of older adults. According to Help Age Kenya, the majority of older people in Kenya, especially those in rural areas, live in absolute poverty [40]. A recent report, the National Gender and Equality Commission Report, dubbed “Whipping Wisdom,” also established that older adults in Kenya faced various forms of violence, including social stigma, neglect, abandonment, and hindrance from using and disposal of property [41].

Implications

Our study highlights opportunities for interventions and further research. It is important to reiterate that the health challenges faced by OALWH at the coast of Kenya are often interconnected and require a cohesive and collaborative response to achieve maximum benefits. Such interventions should target modifiable factors such as emotional support and integrate needed social and community support, e.g., case management services, food and nutrition support, financial assistance with caregiving responsibilities, and transportation. Context-specific interventions to help OALWH develop and nurture their own coping strategies are also critical in this population. Patient-centred care and patient self-management principles (e.g., self-reliance and empowerment) are critical elements in chronic care and are advocated as universal strategies in international frameworks of chronic care [42]. Integrated care models—which focus on the holistic view of the person by considering both medical and psychosocial needs, e.g., comprehensive geriatric assessment, are likely to improve the patient situation and the treatment outcomes. While OALWH are the primary target of most of the existing interventions in this cohort [43–45], research is required on how to build the capacity of healthcare providers, family members who act as informal caregivers and friends to provide support and care to those ageing with HIV. Future research should also examine the resources and resilience among these individuals to fully understand the vital role of resilience in empowering OALWH to enact processes that buffer health from the identified stressors. Future research is also needed to quantify the existing burden of physical and mental challenges in this population in Kilifi and confirm the risk and protective factors of these challenges. Furthermore, there is an urgent need for research to pilot and test the applicability and effectiveness of interventions underlying the determinants of physical and mental impairments in this setting.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to richly explore the health challenges of OALWH on the coast of Kenya and among the few studies in Kenya. Unlike previous studies, a key strength of this work is that participants comprised a diverse group of stakeholders. This ensured that the views were diverse and contrasted across participant groups. Using a biopsychosocial model helped us obtain a richer insight into the complexity of the identified health challenges. However, our findings emanate from a predominantly rural setting, and circumstances may differ from those in urban areas. Only OALWH who were on long-term HIV treatment were interviewed in this study; thus, their circumstances may also differ from those who are not in care or the newly diagnosed. As is the norm for qualitative studies in general, data collection, analysis, and interpretation are subject to individual influences and researcher biases; nonetheless, we countered this effect by maintaining reflexivity and constant discussion with the research team to provide rigour and credibility to the study.

Conclusion

Our findings provide initial insight into the biopsychosocial challenges confronted by OALWH in a low-literacy Kenyan setting. The participants’ views indicate that mental complaints (especially symptoms suggestive of common mental health conditions and memory difficulties), physical problems (particularly comorbidities and somatic symptoms) and psychosocial challenges (especially poverty, stigma, and discrimination) are of concern among OALWH. Many of the perceived risk factors for these challenges often overlap across the biopsychosocial domains. Our study also highlights several opportunities for interventions and future research to tackle these issues in the study setting. Future research should quantify the burden of these challenges, examine the resources available to these adults, pilot, and test feasible interventions in this setting, and in doing so, aim to improve the lives of older adults living with HIV.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific and Ethics Review Unit. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

PM, CN, and AA conceptualized the study. PM, CN, RW, and AA designed the study. PM programmed the study questions on tablets and managed project data for the entire study period. PM analysed the data. PM, RW, CN, and AA contributed to the interpretation of the data. PM wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all the authors reviewed the subsequent versions and approved the final draft for submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust International Master’s Fellowship to PM (Grant number 208283/Z/17/Z). Further funding supporting this work was from 1) the Medical Research Council (Grant number MR/M025454/1) to AA. This award is jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under MRC/DFID concordant agreement and is also part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union; 2) DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-003). The DELTAS Africa Initiative is an independent funding scheme of the African Academy of Sciences (AAS)’s Alliance for Accelerating Excellence in Science in Africa (AESA) and supported by the New Partnership for Africa’s Development Planning and Coordinating Agency (NEPAD Agency) with funding from the Wellcome Trust (107769/Z/10/Z) and the UK government. The funders did not have a role in the design and conduct of the study or interpretation of study findings.

Author Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of AAS, NEPAD Agency, Wellcome Trust, or the UK government. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this manuscript has been uploaded to medRxiv preprint server [46] ahead of peer review. We would also like to thank all the participants who took part in this study. This work is published with the permission of the director of Kenya Medical Research Institute.

References

1. Autenrieth, CS, Beck, EJ, Stelzle, D, Mallouris, C, Mahy, M, and Ghys, P. Global and Regional Trends of People Living with HIV Aged 50 and over: Estimates and Projections for 2000–2020. PloS one (2018) 13(11):e0207005. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207005

2. Hontelez, JA, de Vlas, SJ, Baltussen, R, Newell, M-L, Bakker, R, Tanser, F, et al. The Impact of Antiretroviral Treatment on the Age Composition of the HIV Epidemic in Sub-saharan Africa. AIDS (London, England) (2012) 26(0 1):S19–30. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283558526

3. Brennan-Ing, M, Ramirez-Valles, J, and Tax, A. Aging with HIV: Health Policy and Advocacy Priorities. Health Edu Behav (2021) 48(1):5–8. doi:10.1177/1090198120984368

4. Milic, J, Russwurm, M, Calvino, AC, Brañas, F, Sánchez-Conde, M, and Guaraldi, G. European Cohorts of Older HIV Adults: POPPY, AGE H IV, GEPPO, COBRA and FUNCFRAIL. Eur Geriatr Med (2019) 10(2):247–57. doi:10.1007/s41999-019-00170-8

5. Rubtsova, AA, Kempf, M-C, Taylor, TN, Konkle-Parker, D, Wingood, GM, and Holstad, MM. Healthy Aging in Older Women Living with HIV Infection: a Systematic Review of Psychosocial Factors. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep (2017) 14(1):17–30. doi:10.1007/s11904-017-0347-y

6. Mwangala, PN, Mabrouk, A, Wagner, R, Newton, CR, and Abubakar, AA. Mental Health and Well-Being of Older Adults Living with HIV in Sub-saharan Africa: a Systematic Review. BMJ open (2021) 11(9):e052810. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052810

7. Brennan-Ing, M. Emerging Issues in HIV and Aging. New York: Sage (2020). Available from: https://www.sageusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/emerging-issues-in-hiv-and-aging-may-2020.pdf; (Accessed August 21, 2021).

8. Siedner, MJ. Aging, Health, and Quality of Life for Older People Living with HIV in Sub-saharan Africa: a Review and Proposed Conceptual Framework. J Aging Health (2019) 31(1):109–38. doi:10.1177/0898264317724549

9. Kuteesa, MO, Wright, S, Seeley, J, Mugisha, J, Kinyanda, E, Kakembo, F, et al. Experiences of HIV-Related Stigma Among HIV-Positive Older Persons in Uganda–a Mixed Methods Analysis. SAHARA-J: J Soc Aspects HIV/AIDS (2014) 11(1):126–37. doi:10.1080/17290376.2014.938103

10. Wright, CH, Longenecker, CT, Nazzindah, R, Kityo, C, Najjuuko, T, Taylor, K, et al. A Mixed Methods, Observational Investigation of Physical Activity, Exercise, and Diet Among Older Ugandans Living with and without Chronic HIV Infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care (2020) 32:640–51. doi:10.1097/JNC.0000000000000221

11. Mabisi, K. The Experiences of Older Women Living with HIV in Northern Uganda. Oxford: Miami University (2018).

12. Schatz, E, Seeley, J, Negin, J, Weiss, HA, Tumwekwase, G, Kabunga, E, et al. “For Us Here, We Remind Ourselves”: Strategies and Barriers to ART Access and Adherence Among Older Ugandans. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):131–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6463-4

13. Kuteesa, MO, Seeley, J, Cumming, RG, and Negin, J. Older People Living with HIV in Uganda: Understanding Their Experience and Needs. Afr J AIDS Res (2012) 11(4):295–305. doi:10.2989/16085906.2012.754829

14. Hlongwane, N, and Madiba, S. Navigating Life with HIV as an Older Adult in South African Communities: A Phenomenological Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(16):5797. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165797

15. Schatz, E, and Knight, L. “I Was Referred from the Other Side”: Gender and HIV Testing Among Older South Africans Living with HIV. PLoS One (2018) 13(4):e0196158. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196158

16. Knight, L, Schatz, E, Lewis, KR, and Mukumbang, FC. ‘When You Take Pills You Must Eat’: Food (In) Security and ART Adherence Among Older People Living with HIV. Glob Public Health (2020) 15(1):97–110. doi:10.1080/17441692.2019.1644361

17. Knight, L, Schatz, E, and Mukumbang, FC. “I Attend at Vanguard and I Attend Here as Well”: Barriers to Accessing Healthcare Services Among Older South Africans with HIV and Non-communicable Diseases. Int J equity Health (2018) 17(1):147–10. doi:10.1186/s12939-018-0863-4

18. Schatz, E, Knight, L, Mukumbang, FC, Teti, M, and Myroniuk, TW. ‘You Have to Withstand that Because You Have Come for what You Have Come for’: Barriers and Facilitators to Antiretroviral Treatment Access Among Older South Africans Living with HIV. Sociol Health Illness (2021) 43(3:624–41. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.13243

19. Harris, TG, Flören, S, Mantell, JE, Nkambule, R, Lukhele, NG, Malinga, BP, et al. HIV and Aging Among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older on Antiretroviral Therapy in Eswatini. Afr J AIDS Res (2021) 20(1):107–15. doi:10.2989/16085906.2021.1887301

20. Kiplagat, J, Mwangi, A, Chasela, C, and Huschke, S. Challenges with Seeking HIV Care Services: Perspectives of Older Adults Infected with HIV in Western Kenya. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):929–12. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7283-2

21. Kiplagat, J, and Huschke, S. HIV Testing and Counselling Experiences: a Qualitative Study of Older Adults Living with HIV in Western Kenya. BMC Geriatr (2018) 18(1):257–10. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0941-x

22. Freeman, E. Neither ‘foolish’nor ‘finished’: Identity Control Among Older Adults with HIV in Rural Malawi. Sociol Health illness (2017) 39(5):711–25. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12531

23. Engel, GL. The Need for a New Medical Model: a challenge for Biomedicine. Science (1977) 196(4286):129–36. doi:10.1126/science.847460

24. Hillman, J. A Call for an Integrated Biopsychosocial Model to Address Fundamental Disconnects in an Emergent Field: An Introduction to the Special Issue on “Sexuality and Aging”. Ageing Int (2011) 36(3):303–12. doi:10.1007/s12126-011-9122-3

25. Halkitis, PN, Krause, KD, and Vieira, DL. Mental Health, Psychosocial Challenges and Resilience in Older Adults Living with HIV. HIV and Aging (2017) 42:187–203. doi:10.1159/000448564

26. Heckman, TG, and Halkitis, PN. Biopsychosocial Aspects of HIV and Aging. Behav Med (2014) 40 (3):81–4. doi:10.1080/08964289.2014.937630

27.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. The 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census: Population by County and Sub-county. Nairobi: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2019). Available from: https://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro=2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-iii-distribution-of-population-by-age-sex-and-administrative-units (Accessed July 23, 2021).

28.Ministry of Health (MOH). Kenya HIV Estimates Report 2018. Nairobi: National AIDS Control Council (2018).

29. Ritchie, J, and Spencer, L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London and New York: Routledge (2002). p. 187–208.

30. Smit, M, Brinkman, K, Geerlings, S, Smit, C, Thyagarajan, K, van Sighem, A, et al. Future Challenges for Clinical Care of an Ageing Population Infected with HIV: a Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis (2015) 15(7):810–8. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00056-0

31. Guaraldi, G, Milic, J, and Mussini, C. Aging with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep (2019) 16(6):475–81. doi:10.1007/s11904-019-00464-3

32. Gouse, H, Masson, CJ, Henry, M, Marcotte, TD, London, L, Kew, G, et al. Assessing HIV Provider Knowledge, Screening Practices, and Training Needs for HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. A Short Report. AIDS care (2021) 33(4):468–72. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1736256

33. Nyongesa, MK, Mwangi, P, Kinuthia, M, Hassan, AS, Koot, HM, Cuijpers, P, et al. Prevalence, Risk and Protective Indicators of Common Mental Disorders Among Young People Living with HIV Compared to Their Uninfected Peers from the Kenyan Coast: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC psychiatry (2021) 21(1):90–17. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03079-4

34. Abubakar, A, Van de Vijver, FJ, Fischer, R, Hassan, AS, Gona, JK, Dzombo, JT, et al. ‘Everyone Has a Secret They Keep Close to Their Hearts’: Challenges Faced by Adolescents Living with HIV Infection at the Kenyan Coast. BMC public health (2016) 16(1):197–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2854-y

35. Cahill, S, and Valadéz, R. Growing Older with HIV/AIDS: New Public Health Challenges. Am J Public Health (2013) 103(3):e7–e15. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301161

36. Munsami, A, Gouse, H, Nightingale, S, and Joska, JA. HIV-associated Neurocognitive Impairment Knowledge and Current Practices: A Survey of Frontline Healthcare Workers in South Africa. J Community Health (2021) 46(3):538–44. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00895-9

37. Ghidei, L, Simone, MJ, Salow, MJ, Zimmerman, KM, Paquin, AM, Skarf, LM, et al. Aging, Antiretrovirals, and Adherence: a Meta Analysis of Adherence Among Older HIV-Infected Individuals. Drugs & aging (2013) 30(10):809–19. doi:10.1007/s40266-013-0107-7

38. Ssewanyana, D, Mwangala, PN, Marsh, V, Jao, I, van Baar, A, Newton, CR, et al. Socio-ecological Determinants of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Drug Use Behavior of Adolescents in Kilifi County at the Kenyan Coast. J Health Psychol (2020) 25(12):1940–53. doi:10.1177/1359105318782594

39. Grov, C, Golub, SA, Parsons, JT, Brennan, M, and Karpiak, SE. Loneliness and HIV-Related Stigma Explain Depression Among Older HIV-Positive Adults. AIDS care (2010) 22(5):630–9. doi:10.1080/09540120903280901

40.Help Age Kenya. Report on Status and Implementation of National Policy on Ageing in Kenya. Nairobi: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2014). Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/workshops/Vienna/kenya.pdf (Accessed December 12, 2021).

41.The National Gender and Equality Commission. Whipping Wisdom: Rapid Assessment on Violence against Older Persons in Kenya. Nairobi: Ministry of Health (2014). Available from: https://www.ngeckenya.org/Downloads/Assessment-on-violence-against-older-persons-in-Kenya.pdf (Accessed December 12, 2021).

42. Thiyagarajan, JA, Araujo de Carvalho, I, Peña-Rosas, JP, Chadha, S, Mariotti, SP, Dua, T, et al. Redesigning Care for Older People to Preserve Physical and Mental Capacity: WHO Guidelines on Community-Level Interventions in Integrated Care. PLoS Med (2019) 16(10):e1002948. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002948

43. Negin, J, Rozea, A, and Martiniuk, AL. HIV Behavioural Interventions Targeted towards Older Adults: a Systematic Review. BMC Public Health (2014) 14(1):507–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-507

44. Knight, L, Mukumbang, FC, and Schatz, E. Behavioral and Cognitive Interventions to Improve Treatment Adherence and Access to HIV Care Among Older Adults in Sub-saharan Africa: an Updated Systematic Review. Syst Rev (2018) 7(1):114–0. doi:10.1186/s13643-018-0759-9

45. Bhochhibhoya, A, Harrison, S, Yonce, S, Friedman, DB, Ghimire, PS, and Li, X. A Systematic Review of Psychosocial Interventions for Older Adults Living with HIV. AIDS care (2020) 33:971–82. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1856319

46. Mwangala, PN, Wagner, RG, Newton, CR, and Abubakar, A. Navigating life with HIV as an older adult on the Kenyan coast: perceived health challenges seen through the biopsychosocial model [Internet]. medRxiv [Preprint] p. 35. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.27.22271072 (Accessed June 09, 2023).

Keywords: older adults, sub-Saharan Africa, HIV, Kenya, biopsychosocial challenges

Citation: Mwangala PN, Wagner RG, Newton CR and Abubakar A (2023) Navigating Life With HIV as an Older Adult on the Kenyan Coast: Perceived Health Challenges Seen Through the Biopsychosocial Model. Int J Public Health 68:1605916. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605916

Received: 21 February 2023; Accepted: 02 June 2023;

Published: 15 June 2023.

Edited by:

Alyson Van Raalte, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, GermanyReviewed by:

Zahra Reynolds, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Mwangala, Wagner, Newton and Abubakar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Patrick N. Mwangala, cG13YW5nYWxhMjdAZ21haWwuY29t, cGF0cmljay5ueml2b0Bha3UuZWR1

This Original Article is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Ageing and Health in Sub-Sahara Africa”

Patrick N. Mwangala

Patrick N. Mwangala Ryan G. Wagner4

Ryan G. Wagner4