Abstract

Objectives: Migrants and refugee youth (MRY) in Western nations are less likely to participate in sexual reproductive health (SRH) services. Consequently, MRY are more likely to encounter adverse SRH experiences due to limited access to and knowledge of SRH services. A scoping review was conducted to examine MRY’s understanding of and the implications for inclusive sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) programs and policies.

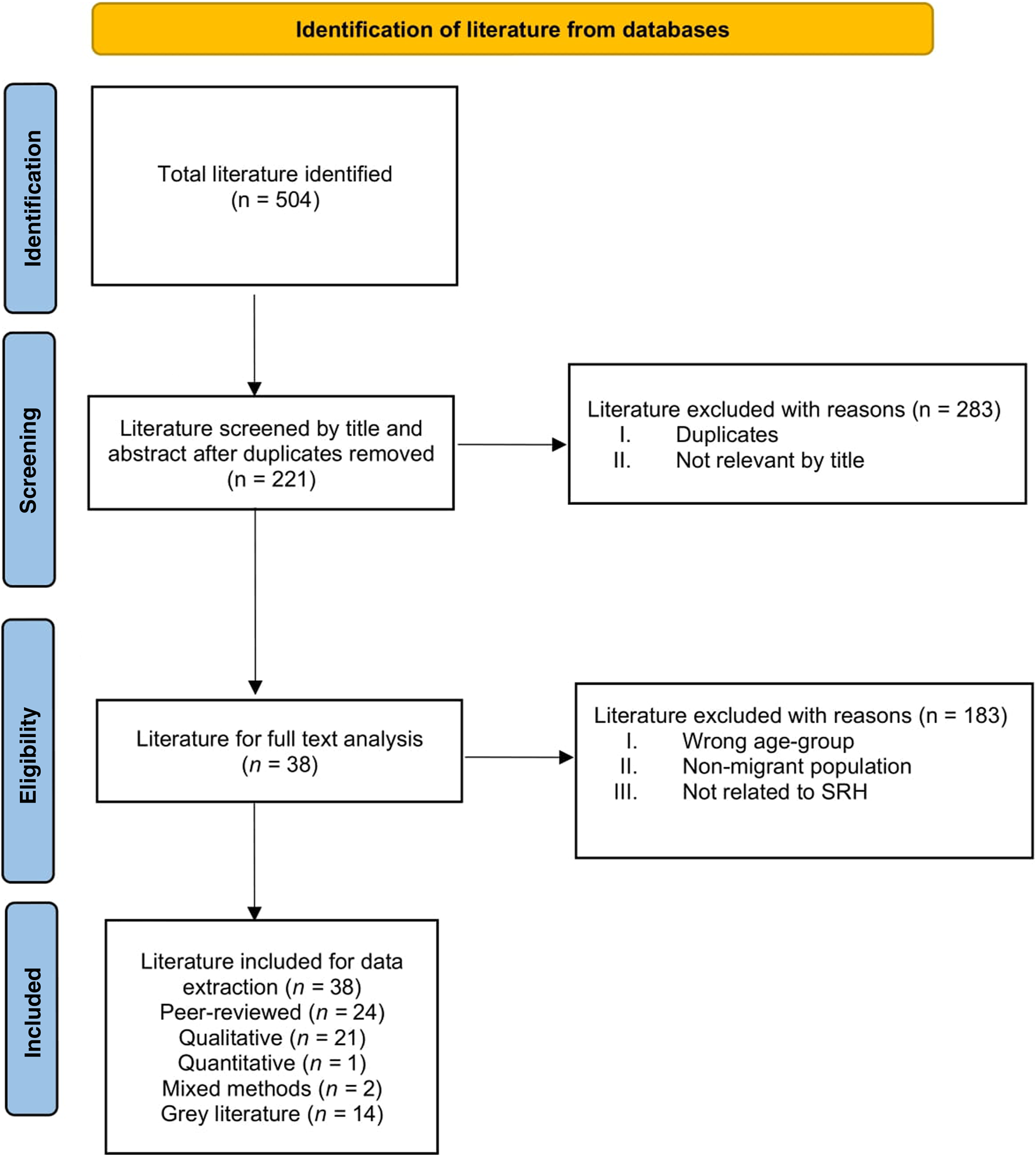

Methods: A systematic search of literature across seven academic databases was conducted. Data were extracted following Partners for Dignity and Rights’ Human Rights Assessment framework and analysed using the thematic-synthesis method.

Results: 38 literature (peer-reviewed, 24 and grey, 14) were considered eligible for inclusion. The findings highlighted significant barriers and the under-implementation of SRHR support and services by MRY. Key policy implications include a need for programs to support MRY’s SRHR education, diversity, equity and inclusiveness and privacy protections.

Conclusion: The review shows that the emerging evidence on MRY SRHR suggests gaps in practices for resourcing policies and programs that promote sustainable SRH for vulnerable populations. Policies for MRY’s SRHR should prioritise programs that focus on diversity, equity and inclusion with targeted education and community resourcing strategies for sustainability.

Introduction

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) is a fundamental human right and central to Migrant and Refugee Youths’ (MRY) knowledge and agency relating to SRHR. Migrant and Refugee Youth (MRY) refers to young individuals (between 10 and 24 years old) who have left their country of origin due to various reasons, such as conflict, persecution, or economic instability, seeking better opportunities and protection [1, 2]. International students (aged 16–24) are included as MRY because they are migrants in the country they choose to study, although their migration experience may differ [3]. The challenges faced by migrant or refugee youth, such as uncertainty regarding the length of time to settle, language barriers, cultural differences and limited knowledge and access to services in a new country, make it imperative to study the sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues that they may face. MRY’s knowledge, experiences and agency are seldom considered [4], especially in low-resource settings [2, 5] due to their experiences of social disparities, discrimination and limited social networks and support systems in their new home country [2, 6–8]. This is despite the fact that it is clear that the pathway to optimising and improving MRY’s SRHR agency, decision-making and wellbeing outcomes can only be achieved by centring youth voices [9].

Literature shows lower levels of SRHR knowledge and literacy, limited access to social and Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) services, higher rates of teenage and unplanned pregnancy, and longer-lasting treatable STIs among MRY compared to their non-migrant counterparts [10, 11]. The 2018 data published by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention [12] shows that STIs were significantly high, with an infection rate of one in five youth aged 15–24 [12]. Another 2018 study reported STI notification among youth represented 10%, 14% and 24% rise in Chlamydia, Gonorrhoea and Syphilis, respectively, with susceptibility higher among youth aged 15–24 (and ages 15–34 high susceptibility to syphilis), representing an estimated 80% of case occurrences despite the under-reporting of cases [13]. Within this age range, women are more likely to be diagnosed than men [13]. Although these data were not disaggregated for MRY, literature [10, 11] suggests that MRY may be disproportionately represented in these statistics. Unlike their non-migrant counterparts, MRYs are less likely to become aware of being infected, the nature and impact of STI, knowledge of and access to support services, and most likely transmit the STI inadvertently to others or suffer complications from an untreated infection as a consequence [14, 15]. This indicates significant human rights inequity, given the disparity between MRY and non-migrant youth.

Human Rights Model and Migrant and Refugee Youth’s SRHR

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1946) outlines thirty fundamental human rights and are essential for holistic SRH and wellbeing. These rights are condensed into five principles in the Partners for Dignity and Rights (PFDAR) framework [16, 17] used to assess a program or action’s compliance with human rights principles. The principles [16, 17] are:

Universality: Affirms that quality healthcare is a fundamental human right for all (Aligns with MIPEX’s health principle) [18, 19].

Equity: Mandates equitable distribution of resources and services eliminating systemic barriers to access.

Accountability: Insists that governments establish mechanisms to enforce human rights standards, holding all entities accountable.

Transparency: Require that governments disclose all information on rights-related decisions and institutional management.

Participation: Insists on the rights of everyone to participate in decisions impacting their rights, with government support for civil society’s involvement in healthcare-related decisions.

Applying the PFDAR framework to SRH underscores the need for a comprehensive consideration of human rights, including sexual rights and obligations, for wellbeing in this area. This enables the formulation of recommendations that recognise diverse identities and experiences, enhancing accessibility and efficiency of health services. It addresses specific needs and challenges faced by MRY in their SRHR context, providing better value for expenditure (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Partners for dignity and rights human rights assessment framework (Scoping Review, International, 2020–2022).

The PFDAR framework, with its human rights emphasis and ability to integrate the strengths of the MIPEX Health strand [18, 19] is a suitable choice for understanding and addressing MRY’s unique SRHR needs. This approach can foster a more inclusive and effective SRHR plan for MRY, ultimately promoting their wellbeing and protecting their rights.

Research Question

This scoping review explored the emerging evidence on MRY’s sexual and reproductive behaviour and outcomes. Our specific research questions were:

1. What SRHR needs do MRY perceive in their life situations?

2. What are the policy implications of the emerging evidence on MRY-inclusive SRHR programs and practices?

Findings may clarify the role and design of MRY-focused SRHR programs that are equitably designed to support the demography.

Methods

Research Design

In line with Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [20], a systematic scoping review was conducted to identify literature (including grey and peer-reviewed literature) that investigated SRHR programs and policies for MRY.

Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted in March 2022 across seven electronic databases, including PsycINFO, ProQuest Central, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL Plus. A primary search on ProQuest Central aided in identifying keywords in titles and abstracts. Following refinement with the research team and university library staff, parameters such as location, population, and related SRH phenomena were established. For exhaustive results, supplementary searches were performed on Australia Policy Online, Google, and Google Scholar, and reference lists from selected literature were examined (Table 1). Grey literature, including reports from organizations like Family Planning and Red Umbrella Sexual Health and Human rights association, was also included to enhance the discussion [21].

TABLE 1

| Parameters | Inclusion | Exclusion | Keywords/steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Australia | Non-western countries | (Abstract) Australia OR Australasia OR Oceania OR OECD |

| Language | Written in English | Other languages | Select for English only |

| Time | Any | None | N/A |

| Population | Literature which includes migrant and refugee youths | Literature which focuses on mainstream populations, older people, non-refugees or non-migrant populations or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander | (Abstract) Refugee* OR Asylum Seeker OR Migrants OR Culturally and Linguistically Diverse OR Ethnic minority OR socially disadvantaged group OR CALD OR Cultural OR Racial OR Vulnerable group OR |

| Immigrant OR Emigrant OR Boat People OR Illegal Immigrant OR Displaced Person* OR Non-Native OR Foreigner OR Foreign National OR Stranger OR Alien OR Visible minority OR Visual minority OR | |||

| OR Non-White OR | |||

| Expatriate OR Exile OR Newcomer OR Settler OR Escapee OR Fugitive OR Runaway OR Outcast OR Returnee OR Stateless Person | |||

| OR Language OR English as Second Language OR Language other than English OR Language Background other than English OR English as an Additional Language or Dialect | |||

| AND | |||

| (Title) Youth OR Young* OR Teen* OR Adolescen* OR Young Adult | |||

| Phenomena/Target | Studies concerned with the participants’ Sexual Health, Reproductive Health and/or Rights | Not concerned with the participants’ Sexual Health, Reproductive Health and/or Rights | AND (Title) |

| Sex* OR Sexually Active OR Family planning OR Sexually transmitted infection OR Sexual relationship OR Sexual prefer* OR Sexual urge OR Contracept* OR Unprotected sex OR Ovulation OR Sexual dysfunction OR Sexual Health OR Reproductive health OR Sexual Education OR Sexual health literacy OR Sexual and reproductive wellbeing OR Sexual reproductive health and wellbeing OR Sexual reproductive rights OR Safe sex OR Sexual activity OR Women and Birth OR Condom OR STI OR Prophylactic OR Pregnan* OR Unwanted Pregnancy OR Teenage Pregnancy OR Termination OR Abortion OR Long active reversible contraception OR | |||

| Rights OR Reproductive Rights OR Sexual Rights OR Access OR Independence OR Personal choice OR Entitle* OR Prerogative OR Privilege OR Sexual Liberty OR Human rights | |||

| Study/literature type | Grey literature and Peer-reviewed academic literature | N/A | |

| Google Modified Search | |||

| Step 1: Refugee* OR Asylum Seeker OR Migrants OR CALD AND Youth OR Young* OR Teen* OR Adolescen* AND Sex* OR Sexually Active OR sti OR std OR sexual right AND Policy OR Policies OR Program* OR Report OR Strateg* AND Australia OR Australasia OR Oceania—first 5 pages = 50 results | |||

| Step 2: Review full article for the above key terms with a particular focus on identifying Migrant and refugee youth specific discussion (e.g., youth, young person, adolescent, teenager) = 5 results | |||

| Step 3: Qualitative analysis of 18 included grey literature | |||

Summary of the inclusion/exclusion criteria and keywords (Scoping Review, International, 2020–2022).

The * is a function added during the search for included articles in the scientific database to include papers that has words related to the search term/s.

The search strategy details, including search terms, combinations, and the use of Boolean operators for population keywords, are summarised in Table 1. Figure 2 shows a PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of identified literature from databases.

FIGURE 2

Article selection flow diagram based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Tricco et al.’s 2018 extension for Scoping Reviews (Scoping Review, International, 2020–2022).

The literature review included English-only publications without date restrictions, focusing on youth (16–24 years) of migrant or refugee background. We used SRHR-related search terms to capture both peer-reviewed and grey literature, ensuring a comprehensive and accurate review of existing evidence [22].

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Using Thomas and Harden’s thematic synthesis method [23] (see Tables 2, 3), data from the included literature was extracted, analysed, and interpreted. This inductive process involved line by line coding of primary studies results, discussions and conclusions, developing descriptive themes, and generating analytical themes for a synthesised results presentation. All authors reviewed and agreed on the final result.

TABLE 2

| Author | Year | Study design | Setting (city not provided) | Outcome/Domain | Sample size | Age group included in review | Gender | Population background | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botfield et al. | 2020 | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | MRY perspectives on pregnancy and abortion | 27 | 16–24 | 16 females; 11 males | Multiple backgrounds (including: African, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese) | 100% |

| Botfield et al. | 2018a | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | MRY engagement with SRH care in General Practice (GPs) | 27 | 16–24 | 16 females; 11 males | Multiple backgrounds (including: African, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese) | 100% |

| Botfield et al. | 2018b | Qualitative | Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States | Promoting SRH among MRY using digital storytelling | 28 | 15–24 | Children, young people 18; Adult, 5; mixed, 5 | Culturally diverse | 100% |

| Botfield et al. | 2018c | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | MRY perspectives on the significance of generation on SRH care | 27 | 16–24 | 16 females; 11 males | Multiple backgrounds (including: African, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese) | 100% |

| Botfield et al. | 2018d | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | MRY SRH information sources, and education | 27 | 16–24 | 16 female, 11 male | Multiple backgrounds (including: African, Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese) | 100% |

| (+34 “key informants”) | |||||||||

| Botfield et al. | 2017a | Qualitative | Sydney NSW | Engaging MRY with SRH promotion and care | 23 | Median: 18 | Multiple backgrounds/Healthcare professionals | 100% | |

| Botfield et al. | 2017b | Qualitative | NSW, VIC & | Complexities of engaging young CALD with SRH promotion | 23 | Median: 18 | 17 female, 6 male | Healthcare professionals | 100% |

| Botfield et al. | 2016 | Qualitative | Australia | CALD youth and their use of services for SRH needs | 120 | 18+ | Multiple backgrounds | 100% | |

| Chung et al. | 2018a | Mixed methods | Western Australia and South Australia | Young African-background women’s understandings of sexual violence and coercion | 17 | Median 22 years | All Female | African background (born: Zimbabwe [5], Kenya [8], Sierra Leone [2] and South Sudan [2]) | 60% |

| [only qualitative relevant to this review] | (+81 agency participants, 23 service providers) | ||||||||

| Dean et al. | 2017a | Quantitative | Queensland | SRH knowledge and practices among young Sudanese Queenslanders | 229 | 16–24 | 80 female, 149 male | Sudanese | 100% |

| Loftus | 2008 | Qualitative | Japan | Sexuality, pedagogy and gender among Japanese teen | NA | Teen | NA | Japanese | 60% |

| Manderson | 2002 | Mixed methods | Queensland | Young Filipina’s SRH issues and understandings | 40 | 14–25 | All Female | Filipino | 60% |

| McMichael | 2010 | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Sexual health risk and protection among MRY | 142 | 16–25 | 67 males, 75 females | Multiple backgrounds | 80% |

| McMichael and Gifford | 2009 | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Promoting Sexual literacy among MRY | 142 | 16–25 | 67 Males, 75 females | Multiple backgrounds: Iraq, Afghanistan, Burma, Sudan, Liberia, and Horn of Africa countries | 100% |

| Meldrum et al. | 2014 | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Young Muslim women’s SRH needs and knowledge | 11 | 18–25 | All female | Mixed-backgrounds: including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Malaysia, Fiji, Somalia, Pakistan | 100% |

| Ngum Chi Watts et al. | 2015a | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Experiences of African background teen/early mothers | 16 | 17–30 years | All Female | African background (born: Sudan [10], Liberia [3], Ethiopia, Burundi, Sierra Leone) | 100% |

| Rawson et al. | 2009 | Qualitative (Grounded Theory methodology) | Australia | Influence of culture on utilisation of SRH services among Vietnamese Youth | 15 | 18–25 | All female | Vietnamese | 100% |

| Rawson et al. | 2010 | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Acquisition of sexual knowledge for Vietnamese-Australian Women | 15 | 18–25 | All female | Vietnamese | 100% |

| Robards et al. | 2019 | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | Healthcare equity and access for marginalised young people | 41 | 12–24 | 9 female, 4 male | Multiple backgrounds: Refugees | 100% |

| Usher | 2019 | Qualitative | Australia, Canada | Sexuality: MRY discourse of silence, secrecy and shame | Childhood (0–12), Adolescent [13–17] | All female | Multiple backgrounds | 100% | |

| Rawson and Liamputtong | 2010 | Qualitative | Melbourne, VIC | Vietnamese-Australian women’s SRH knowledge seeking, education and sources | 15 | 18–25 | All female | Vietnamese | 100% |

| Rogers and Earnest | 2014 | Qualitative | Brisbane, QLD | Intergenerational experiences and knowledge of SRH among Sudanese and Eritrean women | 5 young women, 8 older women, key informants) | 18–30 | All female | Sudanese and Eritrean | 100% |

| Rogers and Earnest | 2015 | Qualitative | Brisbane, QLD | SRE (sexuality and relationships education) and SRH experiences among Sudanese and Eritrean women | 5 young women, (8 older women, key informants) | 18–30 | All female | Sudanese and Eritrean | 100% |

| Wray et al. | 2014 | Qualitative | Sydney, NSW | SRH constructions and experiences of young Muslim migrant women | 10 | 18–25 | All female | Birth country: Iraq [2], Iran [2], Afghanistan [4], Bangladesh [1] and Pakistan [1] | 100% |

Characteristics of peer reviewed literature included in the scoping review (Scoping Review, International, 2020–2022).

TABLE 3

| Author | Year | Article title | Literature type (study design) | Setting (city not provided) | Outcome/domain | Sample size | Age group included in the literature | Gender | Population background | Theoretical/analytical approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oriti, 2017 | 2017 | Experts say sexual slavery disturbingly common in Australia: The plight of a young African woman who sought help at a refugee centre in inner Sydney has shone a light on the problem of sexual slavery in Australia | Newspaper article | Australia | MRY (refugee) challenges (sexual slavery) | 1 | 16–24 | F | Refugee Youth (Young African Women) | N/A |

| U.S. Newswire, 2005 | 2005 | American, European Youth Advocate for Reproductive Health, Rights of Young People at First-Ever US-EU Youth Advocacy Summit in Brussels | Newspaper article | United States of America | Advocacy for youth’s reproductive health rights | N/A | Not stated | Not stated | Youth (American, European) | N/A |

| AAP General News Wire, 2014 | 2014 | NSW: Teen refused bail over sex assault of ex | Wire Feed (News) | Australia | MRY sexual attitude | 1 | 16–24 | M | Refugee Youth (African) | N/A |

| Watts, 2014 | 2014 | Nursing: Contraception knowledge and attitudes: truths and myths among African Australian teenage mothers in Greater Melbourne, Australia | Report/Qualitative (Interview) | Australia | MRY SRH information and attitudes | 16 | 16–24 | F | African Australian Teenage Mothers | Intersectionality, cultural competency and Phenomenology/Thematic Analysis |

| Henderson and Conifer, 2016 | 2016 | Refugee raped on Nauru flown to Papua New Guinea for abortion | Newspaper article | Australia | MRY experiences: sexual violence | 1 | 16–24 | F | African Refugee Youth | N/A |

| Kerin, 2015 | 2015 | Iranian asylum seeker and alleged rape victim moved from Nauru to Brisbane for treatment: A 23-year-old asylum seeker | Newspaper article | Australia | MRY experiences: sexual violence | 1 | 16–24 | F | Asylum Seeker Youth (Iranian) | N/A |

| Walker, 2005 | 2005 | Fed: Old male GPs making teenage contraception difficult | Newspaper article | Australia | Impact of service provider knowledge among MRY | N/A | Not stated | F | Youth | N/A |

| Australian Human Rights Commission, 2019 | 2019 | Australian Human Rights Commission: U.N. Calls for National Action to Protect the Rights of Children and Young People in Australia | Newspaper article | United States | Human rights of Children and Young People | N/A | Not stated | N/A | Youth | N/A |

| Peta, 2015 | 2015 | Abyan to fly back to Australia from Nauru: The young pregnant Somali refugee | Newspaper article | Australia | MRY experiences: Pregnancy and sexual violence | 1 | 16–24 | F | Refugee Youth (Somali) | N/A |

| Carmody, 2013 | 2013 | Young people, sexual violence prevention and ethical bystander skills | Journal/Mixed method | Australia | Young people, sexual violence prevention | 153 | Median: 18 | Mixed | Youth | Social Norm theory/Thematic Analysis |

| Nightingale, 2015 | 2015 | Doctors call for teens to have better access to sexual healthcare: The Royal Australasian College of Physicians | Newspaper article | Australia | Service provider knowledge in healthcare | N/A | Not stated | N/A | Youth (Australian/Marginalised) | N/A |

| Bateson et al. | 2018 | Talking to young people from migrant and refugee backgrounds about sexual and reproductive health: what have we learned and where do we go from here? | Report/Qualitative (Doctoral Research) | Australia | MRY and SRH report | 27 | 17–24 | 16 females; 11 males | Migrant and Refugee Youth (African, Argentine, Asian, Brazilian, Cambodian, Hazara | Not specified/Thematic Analysis |

| Allimant and Ostapiej-Piatkowski, 2011 | 2011 | Supporting women from CALD backgrounds who are victims/survivors of sexual violence | Report | Australia | CALD: Sexual violence | N/A | N/A | F | CALD Women | NA |

| Aiyar, 2020 | 2020 | “It’s better to have support”: Understanding wellbeing and support needs of gender and sexuality diverse migrants in Australia | Thesis/Qualitative (Semi-structured interview) | Bangladesh, Brazil, Central Europe, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan and Philippines | MRY SRH and wellbeing | 15 | Median: 18 | Mixed | Migrant Sexuality Diverse Youth | Intersectionality/Thematic Analysis |

Characteristics of grey literature included in the scoping review (Scoping Review, International, 2020–2022).

Quality Assessment

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [24] was used for quality assessment of peer-reviewed literature. The studies were rated (in percentages) based on the criteria met, each worth 20% [25, 26]. The assessment process identifies potential study limitations or biases, providing a nuanced understanding of the evidence and guiding interpretation and recommendation [26]. It assures the quality and reliability of evidence synthesis on MRY’s SRHR. The assessment revealed high confidence in the scientific merits of the included literature.

Results

Of the 504 potentially relevant articles identified, 38 literature (peer-reviewed n = 24, grey n = 14) were included in the systematic scoping review (Tables 2, 3).

Sample

The characteristics of each literature are summarised in Tables 2, 3. Using the human rights framework [16, 17] the synthesized perspectives and reports concerning MRY cover topics like SRH education scarcity, sexual violence, limited sexual healthcare access, and social and cultural isolation. A female MRY population was the focus of 44.7% of the 17 articles, while the general MRY population comprised 55.3%. Migrant youth from thirty multicultural backgrounds and nationalities appeared in 79% of the literature, with Africa [12], Asia [8], and the Middle East [6], Europe [3] and Melanesia [1]. The review also included nine newspaper articles and three organizational internal reports, providing a well-rounded SRH perspective. These pieces shed light on government policies, SRH awareness impacts, and the social, economic, and cultural isolation of MRY. Young women’s SRHR experiences were emphasized in twelve peer-reviewed and three grey literature, tackling issues like taboos, contraceptive use, education scarcity, and sexual violence. Most of the literature (84%) was set in Australia [32], with the rest from the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, Asia, Brazil, and Central Europe.

Research Foci and Theoretical Approach

Among the 38 included documents, a significant number primarily evaluated or reported on the attitudes of the community and government attitudes towards MRY’s SRH [15], SRH services [9], support to MRY’s SRHR [8] and the impact of existing policy on the MRY [9]. Other literature indirectly or directly explored the impact of existing SRH practices on healthcare outcomes [12]. Most studies implicitly or explicitly aimed to make recommendations about improving SRH support for MRY including enhancing education curriculum to include SRHR, multicultural competency training and practice, and improving SRHR awareness in practice among healthcare professionals. Only 12 documents explicitly indicated the use of a theoretical approach to guide the literature, utilising theoretical frameworks such as intersectionality, cultural competency, phenomenology, narrative, constructive grounded theory and social norm theory.

Research Design and Methodology

Out of the 38 documents, 24 used qualitative methodology with focus groups, surveys, and interviews as common data collection strategies. Three articles [27–29] employed mixed methods, and one [30] utilised quantitative methodologies (see Tables 2, 3).

Major Findings

Four major themes emerged from line-by-line coding of the included literature, aligning with four PFDAR [10] human rights principles (Universality, Equity, Accountability and Participation). The themes are Limitations of Sexual Reproductive Health Education, Systemic Discrimination—Restricted Access to Sexual Healthcare, Inequity–Sexual Violence, Coercion and Exploitation, and Anonymity and Privacy Risks. For clarity, brevity and readability, results are presented collectively with example citations for major findings.

Theme 1: Limitations of Sexual Reproductive Health Education

The literature highlighted limitations of SRH education as central to accessing other rights [27, 28, 31–39], impacting not only migrant youth but also the general youth population [36, 39, 40]. In line with the PFDAR human rights universality and participation measures, which advocates for unrestricted access and MRY involvement in SRH services, sub-themes like exclusionary practices within the health system [27, 32, 40] and inefficient culturally specific programs for MRY were revealed [27, 28, 36, 37, 41–43] breaching the PFDAR’s Participation principle and MIPEX’s education and anti-discrimination policies, as they require education systems to cater to the needs of migrant youth [16–19].

SRH education was often found lacking in cultural understanding, negatively impacting young people’s attitudes and behaviours towards SRH programs such as family planning services and sexual health clinics. The need for culturally safe programs for MRY participation [27, 37, 43, 44] and inclusion of safe sex in national school curriculum by government and policymakers was underscored [31, 35, 45–47]. Some literature associated practices of sexual exploitation, coercion, violence and gender inequality among youth to limited SRH education and non-existent gendered policy, programs and practices [43–45, 48].

Theme 2: Systemic Discrimination—Restricted Access to Sexual Healthcare

Systemic discrimination [40, 49–51] manifesting as limited or delayed access to sexual healthcare and social and cultural isolation, emerged as a theme violating the PFDAR’s Equity principle. Some articles demonstrated that youth either could not access information on SRH topics or were deterred by the stigma associated with accessing sexual health services [27, 32, 34, 37, 38, 42, 45, 51–54]. Marginalized groups, like youth with disabilities and the LGBTQI+ community faced higher SRH discrimination [32, 44, 45, 51, 55]. Particularly, women experienced intersections of racism and sexism, along with the challenges of living on limited incomes, affecting service access [27].

The Accountability principle was violated, evidenced by an instance of systemic discrimination in the form of a discriminatory and inadequate police response towards a refugee youth who had been raped and was found disoriented on the street [50]. The rape survivor was held in police van for 45 min while the officers watched celebratory fireworks before taking her to the hospital. Some articles highlighted government’s negligence toward MRY rape survivors in immigration detention, resulting in higher suicide risks [15, 40, 43, 49, 50, 56].

Literature recommended acknowledging the background (life and experiences) and influences (culture, community, and family) of naturalised migrant youth (e.g., African-Australian youth) in healthcare services and programs development for MRY [28, 34, 41, 57]. This recommendation aligns with the PFDAR’s Participation principle, endorsing the inclusion of migrant youth perspectives in healthcare decision-making.

Theme 3: Inequity–Sexual Violence, Coercion and Exploitation

Inequity, underscored by persistent instances of sexual violence, coercion and exploitation, surfaced as a critical theme [27, 28, 33, 40, 44, 49, 50, 58]. These instances ranged from rape, forced prostitution, sexual slavery, sexual assault, victim-blaming, to trafficking and forced labour, often inhibiting disclosure due to fear of reprisal and anonymity concerns in ethnic minority communities and dissuade a reporting culture among some service providers [28, 40, 50]. Particular report highlighted international students as a vulnerable but overlooked migrant group severely affected by sexual abuse [44]. The nature of mandatory reporting further discourages disclosure among MRY due to potential legal implications and impacts on their settlement [27]. The findings also highlight gaps in government awareness of sexual slavery and forced labour, particularly in migrant and refugee communities, violating the Equity and Accountability principles of the PFDAR framework [33]. These findings illustrate the heightened vulnerability of MRY to human rights abuses due to discrimination and lack of resources, emphasising systemic barriers and inequitable access to services.

Theme 4: Anonymity and Privacy Risks

Findings show that cultural, community, and family taboos shape MRY’s understanding of SRH, impacting their ability to access services due to fears of judgement and breaches of anonymity, especially in closely-knit communities [32, 36, 45]. This is in variance with PFDAR’s Equity and Participation principles. Fear extends to engaging with older or culturally similar health professionals, expecting judgement or unfriendliness [32, 36, 38, 39, 45, 47].

Use of interpreters further discourages help-seeking due to concerns that interpreters could be community figures, thus violating the Equity principle. Literature emphasised youth’s rights to confidentiality in professional interactions [32, 45], aligning with the PFDAR’s Accountability principle. Other literature expressed some health professionals’ unawareness of legal age of consent may negatively impact their services, with women often facing community and practical barriers to help-seeking [27, 34, 45]. Consequently, this may deter MRY from seeking information about STI, pregnancy tests, or contraception [42, 56].

Chung et al.’s [27] focus group (n = 25) suggested a culturally responsive approach to reduce the stigma around discussing sexual topics openly and address violence against women [51]. Reiterating PFDAR’s Participation principle, Carmody [28] proposed using social norm theories to foster supportive normative environments to support individual’s beliefs or attitudes [41]. Further recommendations included emphasizing confidentiality through digital media, creating welcoming environment, promoting discrete waiting areas and discouraging sending confidential mail to youth’s home [36, 44], to align with PFDAR’s Equity and Accountability principles.

Discussion

The review highlight that the challenges, interactions, and behaviours of MRY have not gained sufficient attention to support the development of culturally safe SRHR policies and programs for MRY. Results show significant misalignment with human rights principles in the framework, leading to persistent human rights challenges for MRY in Western countries [59, 60]. In relation to the Universality principle, the Australian Human Rights 2013 snapshot report [61] highlighted a significant human rights gap with respect to the treatment of refugees and people seeking asylum against Australia’s international obligation. In 2019, the Human Rights Commission [48] found that children do not have substantial rights and therefore proposed strategies to advance the rights of children [62] to align with the principle. While the action in 2019 refers to the rights of children in general, by extension, it disproportionately impact MRY due to additional obstacles such as settlement, cultural and language barriers, and education deficit. Additionally, the call for the government to discontinue the arbitrary detention of children who are refugees or seeking asylum, and invest in children’s wellbeing is also an indication of the recognisable SRH risks faced by youth [48]. Essentially, the Universality principle—which maintains human rights for, regardless of race, gender class or socio-economic status—has not been fully realised for MRY [16, 17, 63].

The findings highlight gaps in adherence to the Participation principle which ensures both civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. The findings indicate an apparent neglect of MRYs’ SRHR possibly due to a lack of awareness among governmental agencies (such as the police and other significant stakeholders), and fear of exploitation among victims [64]. While some literature highlighted the endemic nature of the lack of SRHR conversations, the general findings did not highlight significant advocacy or effective communication strategies at governmental or community levels respectively to highlight the plight of MRYs in addressing their SRHR concerns. Discourses identified mainly involve high-level engagements such as judicial cases or human rights conferences, with limited engagement from migrant communities, particularly the youth. This situation contravenes the Participation principle, which affirms people’s right to partake in decisions impacting them [16, 17, 65].

To uphold principles of Universality and Participation, the findings advocate for the education of key stakeholders to enhance awareness about the challenges MRY face [31, 66, 67]. Stakeholder education through organisation-wide campaigns [68] and grassroots engagement initiatives [69] is found to provide common ground for SRH conversations leading to improved programs and policies. Such engagement facilitates understanding and addressing personal biases [70] and promotes reflection on cultural sensitivity and SRH service provision [71]. Being able to access a culturally safe service can positively influence MRY’s SRH decision-making and improve help-seeking behaviour. As Dune et al. [72] suggest, effective SRH strategies should consider MRY’s experiences in a collaborative culture aimed at dismantling SRH stigma across society.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted MRYs’ SRHR issues, exacerbating existing barriers and inequalities in accessing SRH services and information as healthcare systems were overwhelmed [73–76]. Disruptions in education also hindered access to vital SRHR education, making it more difficult for MRY to receive accurate and culturally appropriate information on SRHR topics [74]. Additionally, the pandemic amplified the vulnerability of MRY increasing their susceptibility to sexual exploitation, violence, and other SRHR-related issues as well as heightened mental health concerns [76, 77]. Recent humanitarian crisis occasioned by the war conflicts in Europe have led to a surge in MRY populations seeking refuge in Western countries [75], further emphasizing the importance of addressing their unique SRHR needs. It is essential for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to remain vigilant in monitoring and responding to these changing global dynamics, as they have a direct bearing on MRY’s SRHR. In light of these challenges, it is crucial to consider the MIPEX Anti-discrimination policies when discussing the PFDAR principles, in order to ensure that MRY populations are adequately supported and protected during public health emergencies and beyond.

Additional findings show a deficit in SRHR education in the education curriculum and the gravity of the impact it has on the migrant and refugee population. However, there is no evidence to show a consideration for functional SRHR education that is focused on MRY needs at a community level. The findings reveal that local organisations are working to raise awareness around STIs such as HIV, calling out risky attitudes to sexual behaviour among youth and the importance of safe sex [35, 78], aligning with studies [79, 80] highlighting youth’s minimised perception of sexual health risks and unplanned pregnancy [11, 31, 81]. Furthermore, advocating safe sex or SRH-related practices is thought to be significantly confronting for faith-based institutions, although, religious institutions and communities are best positioned to influence health promotion among adherents [82]. While considering the challenges for faith-based institutions to contemplate a healthy approach to SRH, the same can be said of ethnic minority families, religious communities, and some older generation health professionals with a cultural cringe about contraception [34], thus making access to contraception difficult for youth. Thus, conscious SRH risk acknowledgment and advocacy among these communities concerning MRY is paramount.

In addition to the lack of SRHR awareness, the issue of sexual violence, coercion, and other sex-related practices are seldom discussed because of the complex implications for victims and their families [27, 83]. In tandem with included literature [83, 84], Keygnaert et al.’s [85] work revealed that sexual violence and coercion continue to impact migrant women substantially extending to psychosocial harm such as shame, vilification, community and practical barriers to help-seeking, and mental health complications including anxiety, depression, poor self-image and suicidal ideation [86–88]. This psychosocial impact infringes upon the participation and universality principles, emphasising that lack of SRHR awareness drives vulnerability to sexual vices, hence the need for improved SRHR awareness to prevent such vulnerabilities within migrant and refugee communities, including LGBTQI [33, 44, 84]. Sexual violence risks also apply to international students, a majority of whom are women, who are seldom included in the conversation [88, 89]. The findings which are also supported by Wallace’s [90] work, show that the awareness of sexual slavery in Western industrialized nations is very low despite a high prevalence of such crimes [91, 92]. Therefore, the integration of MIPEX Anti-discrimination policies [18, 19] with the PFDAR principles [16, 17] is necessary to provide support and protection to, thereby reducing their vulnerability to sexual exploitation and violence.

Therefore, addressing the SRHR issues among MRY requires a holistic approach that involves not only policy changes, but also cultural shifts, community engagement, and education. By acknowledging the unique challenges faced by MRY and incorporating PFDAR human rights principles in conjunction with the MIPEX policies, it is possible to create a more inclusive and equitable society where the rights and wellbeing of all individuals, including MRY, are respected and upheld.

Implications for MRY SRHR Policies, Programs and Practices

SRH education curriculum: Findings suggest that incorporating comprehensive SRH education into the national curriculum is crucial for fostering SRH discussions in education and enhancing SRH knowledge and service use among young people, including MRY [93, 94]. Government and policymakers are encouraged to prioritise SRH education, which could inspire service uptake and further research opportunities for improved policy and practice [93, 94].

Workforce training: Service providers can benefit from training to encourage reflective practices that address potential biases or knowledge gaps [95, 96]. Increased cultural representation among educators and service providers, as suggested by Galagan [97] and Mitchell et al. [98] can enhance service quality and uptake.

Co-design and peer-to-peer education: Involving MRY in shaping SRHR policies and programs is potentially beneficial in empowering them, ensuring culturally responsive solutions [85, 86]. Also, peer education can effectively raise SRH awareness and promote healthy behaviours among MRY [99, 100].

Government commitment to children’s human rights obligations: The review shows significant policy gaps affecting young people’s rights, especially MRY populations. This calls for a governmental review of SRH policy to align with human rights and MIPEX anti-discrimination policies. The aim is to encourage youth participation, including MRY, in SRH decisions. Current child protection and mandatory reporting policies do not adequately consider cultural needs, causing privacy concerns and potential vilification. Parton et al. [101] referring to the child protection policy in England which has experienced high-level criticism, deemed it “a moral panic if not a witch-hunt,” [101] while Redleaf [102] holds that it traumatises families. Therefore, a co-design policy approach with migrant communities is essential [99]. Such a policy revamp would boost MRY’s confidence in understanding their rights, reporting SRH crimes, and enhance their trust in lawmakers and government agencies.

Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

The study provides valuable insights into SRH support needs and policies for MRY but has several limitations. Despite its comprehensive blend of peer-reviewed and grey literature, the review does not sufficiently incorporate MRY perspectives or solutions based on their experiences. This gap undermines the potential of policies and services to fully address their needs. The review overlooks certain underrepresented groups within MRY, such as those with physical disabilities or neuro-divergence. This lack of representation could result in biased policy recommendations that do not cater to the diverse needs within the MRY population.

A significant limitation is the lack of intersectional analysis that considers factors like gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and socio-economic status. Without such analysis, it is challenging to develop comprehensive SRHR policies that address the unique challenges MRY face due to the interplay of these factors. The literature reviewed also shows a disproportionate representation of Australian MRY SRH literature, which reflects a specific sociocultural, political, and economic context even though multiculturalism has not been fully represented given Australia’s short, yet growing migration history for the majority of cultural communities. This implies that MRY’s SRH experiences and views in other industrialised countries with varying degrees of histories and experiences of migration are not fully represented in the findings against the Australian context. This over-representation could potentially limit the breadth of understanding and applicability of findings to other cultural contexts or countries with different migration histories.

The potential role of technology and digital media in addressing MRY’s SRHR needs, particularly in the context of COVID-19, is not highlighted. As many young people have access to smartphones and the internet, technology could offer new opportunities for information dissemination, support, and service provision.

Lastly, bias exists where the studies were limited to those only published in English (when trying to make inferences about MRY, or giving consideration to MRY groups in non-English speaking countries such as France, Greece, Spain, Italy, to list a few, due to the large number of migrants they receive) potentially skewing perspectives and limiting a truly global understanding of MRY’s SRH experiences. This is particularly significant as MRY groups often come from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Future research should address these gaps, incorporate a more intersectional approach, engage directly with MRY, consider the role of technology, and broaden linguistic and geographical scope to provide a more comprehensive understanding of MRY’s SRH experiences and needs.

Conclusion

Promoting increased health literacy, safer sex practices, and a strong awareness of MRY rights, requires a comprehensive acceptance and integration of diversity across systems, institutions, and practices. An important consideration involves disrupting the intergenerational perpetuation of ineffective, often western-centric top-down SRH systems in migrants and refugees’ communities. Within the scope of this study, such disruption is achievable by prioritising youth perspectives and collaboratively designing policies and programs that adequately address their SRHR needs and rights. Essentially, healthcare systems, policymakers, and practitioners should adopt culturally competent principles that cater to diverse needs and forge effective alliances [42, 103]. This commitment is key in supporting MRY’s health and wellbeing [104] and fostering global health equity and social justice. Therefore, collaborative efforts from international stakeholders are necessary to develop culturally appropriate and responsive policies addressing MRY’s unique needs globally.

Furthermore, acknowledging the limitations of the existing literature (including the need for intersectional analysis, diverse perspectives, and consideration of technology’s role in SRHR) particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic) is critical. Addressing these limitations can foster effective global policies and improve MRY’s health and wellbeing. Hence, an inclusive approach prioritizing youth perspectives, cultural diversity, and global context is required to effectively address MRY’s SRHR needs.

Statements

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: MA, TD, PL, and VM. Data curation: MA. Formal Analysis: MA. Investigation: MA. Methodology: MA, TD, SM, PL, and EM. Project administration: MA. Resources: MA and TD. Supervision: TD, SM, PL, and EM. Validation: TD, SM, and PL. Writing—original draft: MA. Writing—review and editing: MA, TD, SM, PL, EM, ZH, and RP. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from the Australian Research Council (grant number: DP200103716). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1.

Cheng I-H Advocat J Vasi S Enticott JC Willey S Wahidi S et al Report to the World Health Organization April 2018. World Health (2018).

2.

Wilding R . Refugee Youth, Social Inclusion, and ICTs: Can Good Intentions Go Bad?J Inf Commun Ethics Soc (2009) 7(2/3):159–74. 10.1108/14779960910955873

3.

Migration IOf. International Students. Berlin: IOM GMDAC (2023). Available from: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/international-students (Accessed April 20, 2023).

4.

Ivanova O Rai M Kemigisha E . A Systematic Review of Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge, Experiences and Access to Services Among Refugee, Migrant and Displaced Girls and Young Women in Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(8):1583. 10.3390/ijerph15081583

5.

Tumwine G Palmieri J Larsson M Gummesson C Okong P Östergren P-O et al ‘One-size Doesn’t Fit All’: Understanding Healthcare Practitioners’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Behaviours towards Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Low Resource Settings: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. Plos one (2020) 15(6):e0234658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234658

6.

Rechel B Mladovsky P Ingleby D Mackenbach JP McKee M . Migration and Health in an Increasingly Diverse Europe. The Lancet (2013) 381(9873):1235–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8

7.

Pottie K Dahal G Georgiades K Premji K Hassan G . Do first Generation Immigrant Adolescents Face Higher Rates of Bullying, Violence and Suicidal Behaviours Than Do Third Generation and Native Born?J immigrant Minor Health (2015) 17:1557–66. 10.1007/s10903-014-0108-6

8.

Castañeda H Holmes SM Madrigal DS Young M-ED Beyeler N Quesada J . Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health. Annu Rev Public Health (2015) 36:375–92. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419

9.

Mengesha ZB Perz J Dune T Ussher J . Talking about Sexual and Reproductive Health through Interpreters: The Experiences of Health Care Professionals Consulting Refugee and Migrant Women. Sex Reprod Healthc (2018) 16:199–205. 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.03.007

10.

Mcmichael C Gifford S . Narratives of Sexual Health Risk and protection Amongst Young People from Refugee Backgrounds in Melbourne, Australia. Cult Health Sex (2010) 12(3):263–77. 10.1080/13691050903359265

11.

Mpofu E Hossain SZ Dune T Baghbanian A Aibangbee M Pithavadian R et al Contraception Decision Making by Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Australian Youth: an Exploratory Study. Aust Psychol (2021) 56(6):511–22. 10.1080/00050067.2021.1978814

12.

Prevention CfDCa. Adolescents and Young Adults Online. Atlanta, GA: Centre for Disease Control (2021). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/adolescents.htm (Accessed October 18, 2022).

13.

Healthed. STI Rates in Australia. Sydney, NSW: HealthEd (2019).

14.

Botfield JR Zwi AB Newman CE . Young Migrants and Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Handbook of Migration and Health. Edward Elgar Publishing (2016). 10.4337/9781784714789.00036

15.

Botfield JR Newman CE Zwi AB . Drawing Them in: Professional Perspectives on the Complexities of Engaging 'culturally Diverse' Young People with Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion and Care in Sydney, Australia. Cult Health Sex (2017) 19(4):438–52. 10.1080/13691058.2016.1233354

16.

PFDAR. Human Rights Assessment Tool for Health Care Reform. New York, NY: Factsheet. Partners for Dignity and Rights (2011). Available from: https://dignityandrights.org/resources/human-rights-assessment-tool-for-health-care-reform/.

17.

PFDAR. Human Rights Assessment of the Medicare for All Act of 2019. New York, NY: Partners for Dignity and Rights (2019). Available from: https://dignityandrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/NESRI_MFA_assessment.pdf.

18.

Solano G Huddleston T . Migrant Integration Policy index. Migration Policy Group (2020). Available from: https://www.mipex.eu/.

19.

Ingleby D Petrova-Benedict R Huddleston T Sanchez E . MIPEX Health strand Consortium. The MIPEX Health Strand: a Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Survey of Policies on Migrant Health in 38 Countries. Eur J Public Health (2019) 29(3):458–62. 10.1093/eurpub/cky233

20.

Tricco AC Lillie E Zarin W O'Brien KK Colquhoun H Levac D et al PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med (2018) 169(7):467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850

21.

Paez A . Gray Literature: An Important Resource in Systematic Reviews: PAEZ. J Evidence-Based Med (2017) 10:233–40. 10.1111/jebm.12266

22.

Stern C Lizarondo L Carrier J Godfrey C Rieger K Salmond S et al Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews. JBI Evid Synth (2020) 18(10):2108–18. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169

23.

Thomas J Harden A . Methods for the Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Research in Systematic Reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol (2008) 8(1):45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

24.

Hong QN Pluye P Fàbregues S Bartlett G Boardman F Cargo M et al Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Amsterdam: IOS Press (2018). p. 1148552. Registration of copyright. Available from: https://content.iospress.com/articles/education-for-information/efi180221.

25.

Pluye P Gagnon M-P Griffiths F Johnson-Lafleur J . A Scoring System for Appraising Mixed Methods Research, and Concomitantly Appraising Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Primary Studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud (2009) 46(4):529–46. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

26.

Grant MJ Booth A . A Typology of Reviews: an Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf Libraries J (2009) 26(2):91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

27.

Chung D Fisher C Zufferey C Thiara RK . Preventing Sexual Violence against Young Women from African Backgrounds. Woden: Australian Institute of Criminology (2018). p. 1–13.

28.

Carmody M . Young People, Sexual Violence Prevention and Ethical Bystander Skills. Conf Pap -- Am Sociological Assoc (2013) 1–25.

29.

Manderson L Kelaher M Woelz-Stirling N Kaplan J Greene K . Sex, Contraception and Contradiction Among Young Filipinas in Australia. Cult Health Sex (2002) 4(4):381–91. 10.1080/1369105021000041034

30.

Dean J Mitchell M Stewart D Debattista J . Sexual Health Knowledge and Behaviour of Young Sudanese Queenslanders: a Cross-Sectional Study. Sex Health (2017) 14(3):254–60. 10.1071/SH16171

31.

Botfield JR Zwi AB Rutherford A Newman CE . Learning about Sex and Relationships Among Migrant and Refugee Young People in Sydney, Australia: ‘I Never Got the Talk about the Birds and the Bees. Sex Edu (2018) 18(6):1–16. 10.1080/14681811.2018.1464905

32.

Nightingale T . Doctors Call for Teens to Have Better Access to Sexual Healthcare: The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2015).

33.

Oriti T . Experts Say Sexual Slavery Disturbingly Common in Australia: The Plight of a Young African Woman Who Sought Help at a Refugee centre in Inner Sydney Has Shone a Light on the Problem of Sexual Slavery in Australia. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2017).

34.

Walker K . Fed: Old Male GPs Making Teenage Contraception Difficult: Stone. Sydney, NSW: AAP General News Wire (2005).

35.

Lauder S . Sex Education Group Raises HIV Alarm; A Sexual Health Group Is Raising the Alarm about the Level of Risky Sexual Behaviour Among Young People. Sydney, NSW: ABC Premium News (2011). 11/30/2011.

36.

Bateson D Carmody C Crozier B Bennett K . Talking to Young People from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds about Sexual and Reproductive Health: What Have We Learned and where Do We Go from Here?. Sydney, Australia: UNSW (2018). Available at: https://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:57028/bin625916e8-56a9-406e-b506-9b5110048659?view=true.

37.

Meldrum R Liamputtong P Wollersheim D . Caught between Two Worlds: Sexuality and Young Muslim Women in Melbourne, Australia. Sex Cult Interdiscip Q (2014) 18(1):166–79. 10.1007/s12119-013-9182-5

38.

Botfield JR Newman CE Bateson D Haire B Estoesta J Forster C et al Young Migrant and Refugee People's Views on Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in Sydney. J Health Section Aust Sociological Assoc (2020) 29(2):195–210. 10.1080/14461242.2020.1764857

39.

Rawson H Liamputtong P . Influence of Traditional Vietnamese Culture on the Utilisation of Mainstream Health Services for Sexual Health Issues by Second-Generation Vietnamese Australian Young Women. Sex Health (2009) 6(1):75–81. 10.1071/sh08040

40.

Peta D . Abyan to Fly Back to Australia from Nauru: The Young Pregnant Somali Refugee Who Is Known by the Name Abyan Will Be Returning to Australia for Medical Assistance. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2015).

41.

Watts M . Nursing: Contraception Knowledge and Attitudes: Truths and Myths Among African Australian Teenage Mothers in Greater Melbourne, Australia. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell (2014).

42.

Botfield JR Newman CE Kang M Zwi AB . Talking to Migrant and Refugee Young People about Sexual Health in General Practice. Aust J Gen Pract (2018) 47(8):564–9. 10.31128/AJGP-02-18-4508

43.

Newton D Keogh L Temple-Smith M Fairley CK Chen M Bayly C et al Key Informant Perceptions of Youth-Focussed Sexual Health Promotion Programs in Australia. Sex Health (2013) 10(1):47–56. 10.1071/SH12046

44.

Allimant A Ostapiej-Piatkowski B . Supporting Women from CALD Backgrounds Who Are Victims/survivors of Sexual Violence, 9. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Institute of Family Studies (2011). p. 1–16.

45.

McMichael C Gifford S . “It Is Good to Know Now…Before It’s Too Late”: Promoting Sexual Health Literacy Amongst Resettled Young People with Refugee Backgrounds, before It’s Too Late': Promoting Sexual Health Literacy Amongst Resettled Young People with Refugee Backgrounds. Sex Cult Interdiscip Q. 2009;13(4):218–36. 10.1007/s12119-009-9055-0

46.

Loftus RP . Review of in the Shadows: Sexuality, Pedagogy, and Gender Among Japanese Teenagers. J Gend Stud (2008) 17(2):179–80.

47.

Ussher J Hawkey A Perz J . Sexual Embodiment in Girlhood and beyond: Young Migrant and Refugee Women's Discourse of Silence, Secrecy, and Shame. In: Lamb,SGilbertJ, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Sexual Development: Childhood and Adolescence. Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press (2019). p. 113–38.

48.

Targeted News Service. Australian Human Rights Commission: U.N. Calls for National Action to Protect the Rights of Children and Young People in Australia. Washington, DC: Targetted News Service (2019). 10/04/2019.

49.

Henderson A Conifer D . Refugee Raped on Nauru Flown to Papua New Guinea for Abortion. Sydney, NSW: ABC Premium News (2016). 05/06/2016.

50.

Kerin L . Iranian Asylum Seeker and Alleged Rape Victim Moved from Nauru to Brisbane for Treatment: A 23-Year-Old Asylum Seeker. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2015).

51.

Robards F Kang M Steinbeck K Hawke C Jan S Sanci L et al Health Care Equity and Access for Marginalised Young People: a Longitudinal Qualitative Study Exploring Health System Navigation in Australia. Int J equity Health (2019) 18(1):41. 10.1186/s12939-019-0941-2

52.

Wray A Ussher JM Perz J . Constructions and Experiences of Sexual Health Among Young, Heterosexual, Unmarried Muslim Women Immigrants in Australia. Cult Health Sex (2014) 16(1):76–89. 10.1080/13691058.2013.833651

53.

Allotey P Manderson L Baho S Demian L . Reproductive Health for Resettling Refugee and Migrant Women. Health issues (2004) 78:12–7.

54.

Aiyar R . It’s Better to Have Support”: Understanding Wellbeing and Support Needs of Gender and Sexuality Diverse Migrants in Australia. Thesis. Adelaide, SA: The University of Adelaide (2020).

55.

Zevallos Z . 'That's My Australian Side': The Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality of Young Australian Women of South and Central American Origin. J Sociol (2003) 39(1):81–98. 10.1177/0004869003039001321

56.

Botfield J Newman C Anthony ZWI . P4.51 Engaging Young People from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds with Sexual and Reproductive Health Promotion and Care in Sydney, australia. Sex Transm Infections (2017) 93. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053264.548

57.

Ngum Chi Watts MC McMichael C Liamputtong P . Factors Influencing Contraception Awareness and Use: The Experiences of Young African Australian Mothers. J Refugee Stud (2015) 28(3):368–87. 10.1093/jrs/feu040

58.

The Spectator. Australian Gets 17 Years for Sex with Young Girl: [Final Edition]. Hamilton, ON: The Spectator (1996). 05/08/1996.

59.

Creek TG . Starving for freedom: An Exploration of Australian Government Policies, Human Rights Obligations and Righting the Wrong for Those Seeking Asylum. Int J Hum Rights (2014) 18(4-5):479–507. 10.1080/13642987.2014.901967

60.

Buller AM Schulte MC . Aligning Human Rights and Social Norms for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Reprod Health Matters (2018) 26(52):38–45. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1542914

61.

Australian Human Rights Commission. Asylum Seekers, Refugees and Human Rights: Snapshot Report 2017. Sydney, NSW: Australian Human Rights Commission (2017). Report No.: 1921449829. Available from: https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/AHRC_Snapshot%20report_2nd%20edition_2017_WEB.pdf.

62.

Isaacs D Triggs G . Australia's Immigration Policy Violates United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. J Paediatrics Child Health (2018) 54:825–7. 10.1111/jpc.14145

63.

Nussbaum MC . Capabilities and Human Rights. Fordham L Rev (1997) 66:273.

64.

Nair VS Banerjee D . “Crisis within the Walls”: Rise of Intimate Partner Violence during the Pandemic, Indian Perspectives. Front Glob women's Health (2021) 2:614310. 10.3389/fgwh.2021.614310

65.

Jones M . Critical Perspectives on Human Rights and Disability Law. In: Inclusion, Social Inclusion and Participation. Brill Nijhoff (2010). p. 57–82.

66.

Ekstrand M Tydén T Darj E Larsson M . Preventing Pregnancy: a Girls' Issue. Seventeen-Year-Old Swedish Boys' Perceptions on Abortion, Reproduction and Use of Contraception. Eur J Contraception Reprod Health Care (2007) 12(2):111–8. 10.1080/13625180701201145

67.

Ayika D Dune T Firdaus R Mapedzahama V . A Qualitative Exploration of post-migration Family Dynamics and Intergenerational Relationships. Sage Open (2018) 8(4):215824401881175. 10.1177/2158244018811752

68.

Chakraborty S . Talking about Gender and Sexual Reproductive Health Rights of Adolescents and Youth in Jharkhand. Asian J Women's Stud (2019) 25(3):468–81. 10.1080/12259276.2019.1647638

69.

Rahman T Khan I . Fathers Involvement in Maternal Health: Need of Father’s Friendly SRHR Consultation Services in Rural Bangladesh. In: PROCEEDINGS of 3rd KANITA POSTGRADUATE, Bangladesh (2016) 16:253.

70.

Sieverding M Schatzkin E Shen J Liu J . Bias in Contraceptive Provision to Young Women Among Private Health Care Providers in South West Nigeria. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health (2018) 44(1):19–29. 10.1363/44e5418

71.

Solo J Festin M . Provider Bias in Family Planning Services: a Review of its Meaning and Manifestations. Glob Health Sci Pract (2019) 7(3):371–85. 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00130

72.

Dune T Liamputtong P Hossain SZ Mapedzahama V Pithavadian R Aibangbee M et al Participatory Action Research: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Young Refugees and Migrants. In: LiamputtongP, editor. Handbook of Social Inclusion: Research and Practices in Health and Social Sciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 1–23.

73.

Mukherjee TI Khan AG Dasgupta A Samari G . Reproductive justice in the Time of COVID-19: a Systematic Review of the Indirect Impacts of COVID-19 on Sexual and Reproductive Health. Reprod Health (2021) 18(1):252–25. 10.1186/s12978-021-01286-6

74.

Lokot M Avakyan Y . Intersectionality as a Lens to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for Sexual and Reproductive Health in Development and Humanitarian Contexts. Sex Reprod Health Matters (2020) 28(1):1764748. 10.1080/26410397.2020.1764748

75.

Shrestha N Shad MY Ulvi O Khan MH Karamehic-Muratovic A Nguyen U-SD et al The Impact of COVID-19 on Globalization. One Health (2020) 11:100180. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100180

76.

Frawley T Van Gelderen F Somanadhan S Coveney K Phelan A Lynam-Loane P et al The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Systems, Mental Health and the Potential for Nursing. Irish J Psychol Med (2021) 38(3):220–6. 10.1017/ipm.2020.105

77.

Nakhaie R Ramos H Vosoughi D Baghdadi O . Mental Health of Newcomer Refugee and Immigrant Youth during COVID-19. Can Ethnic Stud (2022) 54(1):1–28. 10.1353/ces.2022.0000

78.

Hirani K Cherian S Mutch R Payne DN . Identification of Health Risk Behaviours Among Adolescent Refugees Resettling in Western Australia. Arch Dis Child (2018) 103(3):240–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313451

79.

Homma Y Saewyc EM Wong ST Zumbo BD . Sexual Health and Risk Behaviour Among East Asian Adolescents in British Columbia. Can J Hum Sex (2013) 22(1):13–24. 10.3138/cjhs.927

80.

Petersson C Peterson U Swahnberg K Oscarsson M . Health and Sexual Behaviour Among Exchange Students. Scand J Public Health (2016) 44(7):671–7. 10.1177/1403494816665753

81.

Botfield JR Newman CE Zwi AB . Engaging Migrant and Refugee Young People with Sexual Health Care: Does Generation Matter More Than Culture? Sexuality Research and Social Policy. A J NSRC (2018) 15(4):398–408. 10.1007/s13178-018-0320-6

82.

Mpofu E . How Religion Frames Health Norms: A Structural Theory Approach. Religions (2018) 9(4):119. 10.3390/rel9040119

83.

Cameron ES Almukhaini S Dol J Aston M . Access and Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Among Resettled Refugee and Refugee-Claimant Women in High-Income Countries: a Scoping Review Protocol. JBI Evid Synth (2021) 19(3):604–13. 10.11124/JBIES-20-00054

84.

Hawkey AJ Ussher JM Liamputtong P Marjadi B Sekar JA Perz J et al Trans Women’s Responses to Sexual Violence: Vigilance, Resilience, and Need for Support. Arch Sex Behav (2021) 50:3201–22. 10.1007/s10508-021-01965-2

85.

Keygnaert I Guieu A . What the Eye Does Not See: a Critical Interpretive Synthesis of European Union Policies Addressing Sexual Violence in Vulnerable Migrants. Reprod Health Matters (2015) 23(46):45–55. 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.11.002

86.

Iglesias-Rios L Harlow SD Burgard SA Kiss L Zimmerman C . Mental Health, Violence and Psychological Coercion Among Female and Male Trafficking Survivors in the Greater Mekong Sub-region: a Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol (2018) 6(1):56–15. 10.1186/s40359-018-0269-5

87.

Keygnaert I Vettenburg N Temmerman M . Hidden Violence Is Silent Rape: Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. Cult Health Sex (2012) 14(5):505–20. 10.1080/13691058.2012.671961

88.

Hutcheson S . Sexual Violence, Representation, and Racialized Identities: Implications for International Students. Edu L J (2020) 29(2):191–221.

89.

Bonistall Postel EJ . Violence against International Students: A Critical gap in the Literature. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse (2020) 21(1):71–82. 10.1177/1524838017742385

90.

Wallace MR . Voiceless Victims: Sex Slavery and Trafficking of African Women in Western Europe. Ga J Int'l Comp L (2001) 30:569.

91.

Leishman M . Human Trafficking and Sexual Slavery: Australia’s Response. Aust Feminist L J (2007) 27(1):193–205. 10.1080/13200968.2007.10854392

92.

Davy D . Human Trafficking and Slavery in Australia: Pathways, Tactics, and Subtle Elements of Enslavement. Women and Criminal Justice (2016) 26(3):180–98. 10.1080/08974454.2015.1087363

93.

Walker R Drakeley S Welch R Leahy D Boyle J . Teachers’ Perspectives of Sexual and Reproductive Health Education in Primary and Secondary Schools: a Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Sex Edu (2021) 21(6):627–44. 10.1080/14681811.2020.1843013

94.

Hindin MJ Kalamar AM Thompson T-A Upadhyay UD . Interventions to Prevent Unintended and Repeat Pregnancy Among Young People in Low-And Middle-Income Countries: a Systematic Review of the Published and gray Literature. J Adolesc Health (2016) 59(3):S8–S15. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.021

95.

Tsuruda S Shepherd M . Reflective Practice: Building a Culturally Responsive Pedagogical Framework to Facilitate Safe Bicultural Learning. Adv Soc Work Welfare Edu (2016) 18(1):23–38.

96.

Spatt I Honigsfeld A Cohan A . A Self-Study of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Reflective Practice. Teach Edu Pract (2012) 25(1):52–67.

97.

Galagan PA . Tapping the Power of a Diverse Workforce. Train Dev (1991) 45(3):38–45.

98.

Mitchell DA Lassiter SL . Addressing Health Care Disparities and Increasing Workforce Diversity: the Next Step for the Dental, Medical, and Public Health Professions. Am J Public Health (2006) 96(12):2093–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082818

99.

Villa-Torres L Svanemyr J . Ensuring Youth's Right to Participation and Promotion of Youth Leadership in the Development of Sexual and Reproductive Health Policies and Programs. J Adolesc Health (2015) 56(1):S51–S7. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.022

100.

Botfield JR Newman CE Lenette C Albury K Zwi AB . Using Digital Storytelling to Promote the Sexual Health and Well-Being of Migrant and Refugee Young People: A Scoping Review. Health Edu J (2018) 77(7):735–48. 10.1177/0017896917745568

101.

Parton N Berridge D . Child protection in England. In: Child protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations (New York, NY: Oxford University Press) (2011). p. 61.

102.

Redleaf DL . They Took the Kids Last Night: How the Child protection System Puts Families at Risk. ABC-CLIO (2018).

103.

Mengesha ZB Dune T Perz J . Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Women’s Views and Experiences of Accessing Sexual and Reproductive Health Care in Australia: a Systematic Review. Sex Health (2016) 13(4):299–310. 10.1071/sh15235

104.

Fong R . Culturally Competent Practice with Immigrant and Refugee Children and Families. Guilford Press (2004).

Summary

Keywords

youth, human rights, reproductive health, migrant, sexual health, refugee youth

Citation

Aibangbee M, Micheal S, Mapedzahama V, Liamputtong P, Pithavadian R, Hossain Z, Mpofu E and Dune T (2023) Migrant and Refugee Youth’s Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights: A Scoping Review to Inform Policies and Programs. Int J Public Health 68:1605801. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605801

Received

21 January 2023

Accepted

23 May 2023

Published

05 June 2023

Volume

68 - 2023

Edited by

Gabriel Gulis, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Reviewed by

Manuel García-Ramírez, Sevilla University, Spain

Margaret Haworth-Brockman, University of Manitoba, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Aibangbee, Micheal, Mapedzahama, Liamputtong, Pithavadian, Hossain, Mpofu and Dune.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michaels Aibangbee, 19877828@student.westernsydney.edu.au

This Review is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Public Health and Primary Care, is 1+1=1?”

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.