- 1Department of Nursing, Graduate School, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea

- 2College of Nursing, Research Institute of Nursing Science, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, Republic of Korea

Objectives: Adolescents exposed to alcohol have increased risky sexual behaviors (RSBs); however, the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs has to be systematically and quantitatively reviewed. We conducted a meta-analysis of the literature to systematically and quantitatively review the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs in adolescents and young adults.

Methods: We searched for qualified articles published from 2000 to 2020 and calculated pooled odds ratios (ORs) using the random-effect model. We also conducted meta-regression and sensitivity analyses to identify potential heterogeneity moderators.

Results: The meta-analysis of 50 studies involving 465,595 adolescents and young adults indicated that alcohol consumption was significantly associated with early sexual initiation (OR = 1.958, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.635–2.346), inconsistent condom use (OR = 1.228, 95% CI = 1.114–1.354), and having multiple sexual partners (OR = 1.722, 95% CI = 1.525–1.945).

Conclusion: Alcohol consumption is strongly associated with RSBs, including early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners among adolescents and young adults. To prevent the adverse consequences of alcohol consumption, drinking prevention programs should be initiated at an early age and supported by homes, schools, and communities.

Introduction

Alcohol consumption in adolescence can affect hormone secretion and the brain, disrupting secondary sex characteristics and damaging brain cells (1). Alcohol consumption at an early age causes disability and accounts for 13.5% of deaths among those aged 20 to 39, causing social and economic losses across our society along with health issues (2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 26.5% of all adolescents aged 15–19 years of age worldwide are current drinkers, which is approximately 155 million adolescents. The highest prevalence rates of current drinking are in the WHO European Region (43.8%), followed by the Region of the Americas (38.2%) and the Western Pacific Region (37.9%). While heavy episodic drinking (HED) is less common among adolescents than in the total population, it peaks at the age of 20–24 years, with prevalence rates among drinkers in this age group higher than in the total population, except in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Among current drinkers aged 15–24 years, prevalence of HED is high among men, with some studies reporting rates as high as 54.2% (3).

Alcohol consumption during adolescence is one of the factors that increase risky sexual behaviors (RSBs) (4, 5). Adolescents with substance abuse issues, specifically alcohol abuse, had approximately twice as many sexual partners and were 70% more likely to be diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) than adolescents without substance abuse issues (6). According to the literature on the relationship between alcohol consumption and early sexual experience in middle school students: Yu et al (7) reported a 2.35-fold increase in early sexual initiation when drinking alcohol, Hong et al (8) reported a 1.43-fold increase, Ayhan et al (9) reported a 2.13-fold increase, and Bersamin et al. (10) reported a 7.4-fold increase.

Depending on the study, the age of first sexual experience among adolescents varies, with Korean adolescents having their first sexual experience at 13.2 years old on average (11), specifically 12.1 years for boys and 13.9 years for girls. Ayhan et al (9) indicated that the first sexual experience occurred before the age of 14 in most studies. In particular, 13.4% of female adolescents had their first sexual experience after drinking alcohol (5). This early sexual debut increases the risk of unwanted pregnancy and STDs (12). Adolescents not using a condom during sexual experiences was reported at 34.4% in a study by Wilson, Asbridge et al (13), 46.9% in a study by Rios-Zertuche et al (14), and 41.1% in a study by Mlunde et al (15), thereby demonstrating that the rate of condom use among adolescents is very low. Alcohol consumption in adolescents is one of the factors for increasing inconsistent condom use, and Sanchez et al (16) reported that 57.1% of adolescents with drinking alcohol experience did not use condoms during sexual intercourse. The most used definition of binge drinking in research is based on the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)’s definition of a pattern of drinking that brings a person’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08 g/dL or higher, which is typically reached after consuming 4 drinks for women or 5 drinks for men within 2 h (17). This definition is consistent with that used by Wilson et al (13) who found that binge drinking, as defined by the NIAAA, increased inconsistent condom use by 1.1 times among adolescents, and Sanchez et al (16) reported this to be 1.27 times. Inconsistent condom use in adolescents can increase the prevalence of STDs and lead to teenage pregnancies (18).

Alcohol consumption in adolescents increases the probability of having more than three sexual partners by 3.37 times (19). Particularly, compared to female adolescents, male adolescents have a 2.9-fold increase in the likelihood of having multiple sexual partners (13). Moreover, the number of sexual partners increased by 2.41 times in current binge drinkers compared to current light drinkers. Drinking alcohol during adolescence increases the likelihood of regretting having sexual intercourse (19), and if they continue to abuse alcohol after adolescence, these sexual behaviors will likely continue into adulthood (20).

Therefore, alcohol consumption during sexual intercourse reduces sexual inhibition and increases RSBs by impacting adolescents’ judgment. However, studies analyzing the relationship between alcohol consumption and RSBs among adolescents have measured alcohol consumption in various ways according to fragmentary questions, amount of alcohol consumption (glass) or frequency of alcohol consumption, and time point (past alcohol consumption and current alcohol consumption). As the results differ by sex, it is difficult to synthesize and summarize the factors affecting alcohol consumption. Additionally, no meta-analysis has integrated each sex behavior by separating early sexual debut, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners for RSBs, which has a higher risk of STDs and teenage pregnancies—rather than integrating alcohol consumption and sexual experience. Thus, this study conducted a meta-analysis to identify the integrated effect of alcohol consumption in adolescents and young adults on the three types of RSBs and to determine whether the effect differs according to sex (male and female). Additionally, this study focused on analyzing the relationship between early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners among RSBs due to alcohol consumption, and aimed to provide the derived results as fundamental data for health education and program development for safe sexual behaviors and prevention of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults.

Methods

Design

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, following the protocol reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) Statement (21). The study protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database under the registration number CRD42022301637.

Search Strategy

Eight electronic bibliographic databases were used: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, EBSCO, PubMed, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Database Periodical Information Academic (DBpia, Korea), and Research Information Sharing Service (RISS, Korea). These were chosen since they comprehensively covered relevant literature in our field of study. Additionally, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO are well-known and widely used databases in healthcare and psychology research, respectively. Korean databases, DBpia and RISS, allowed us to retrieve relevant studies published in the Korean language.

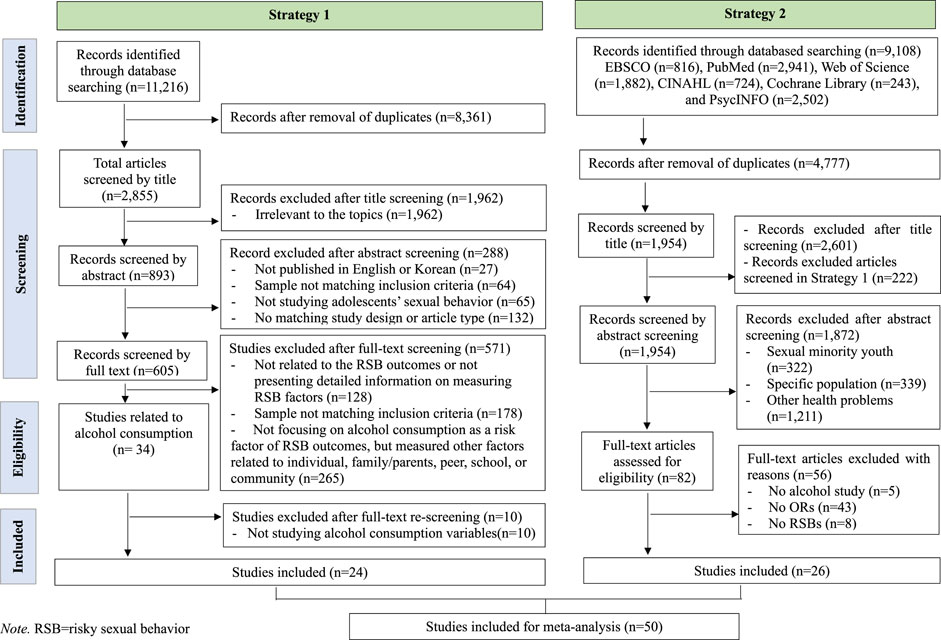

We conducted a comprehensive literature review using two search strategies. The first strategy was to select studies that investigated the relationship between alcohol consumption and RSBs and included alcohol consumption as an independent variable affecting RSBs from large systematic reviews of RSB-related factors in individuals, peers, schools, and communities. We used the general keywords “factor(s) AND sexual behavior” or “risky sexual behavior” and “adolescent(s) or young adult(s)” through the title and abstract fields to identify relevant articles published between January 2000 and July 2020. The process of literature search, screening, and selection is presented in a separate research article (Ahn and Yang, 2022) for more detailed information. In the systematic review (Ahn and Yang, 2022), we included studies that examined the relationship between self-esteem and RSBs. However, for this meta-analysis, we selected studies that investigated the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs. This distinction is highlighted in the study inclusion criteria and is further explained in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. Flow chart of the selection process of studies included in the meta-analysis (Worldwide, 2001–2021).

The second search strategy used specific keywords to identify relevant articles. For example, in PubMed, we searched for articles using the following search terms: “Young Adult” [Mesh] OR “young adult*” OR “Adolescent” [Mesh] OR “adolescent*” OR “teen*” OR “youth*”), AND condom use (“Unsafe Sex” [Mesh] OR “unsafe sex” OR “unprotected sex” OR “high-risk sex” OR “unprotected intercourse” OR “condomless sex” OR “condom use” OR “condom compliance”) OR early sexual initiation (“Coitus” [Mesh] OR “Coitus” OR “First intercourse” OR “Sexual intercourse” OR “early sexual debut” OR “early sex*” OR “early sexual initiation”) OR multiple sexual partner (“Sexual Partners” [Mesh] OR “sexual partner*” OR “sex partner*” OR “multiple sexual partner*” OR “multiple sex partner*”).

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Full-text versions of the retrieved articles were screened based on the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) target population aged 15–24; 2) investigating the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs; and 3) defined early sexual debut as initiation before the age of 14 years. The exclusion criteria were: 1) if the target populations were sexual minority youth (e.g., gay, bisexual, lesbian, homosexual, men who have sex with men, or transgender); specific population (homeless, juvenile, or military); 2) focusing on HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), STI (Sexually transmitted infections), or other mental health problems; 3) did not report the odds ratio of early sexual debut, inconsistent condom use, multiple sexual partners separately; 4) did not report direct alcohol consumption association; and 5) insufficient information to calculate effect size or insufficient effect size to convert to odd ratio. We excluded studies that focused on sexual minority youth because our primary focus was on the general adolescent population. While we acknowledge the importance of understanding the relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behavior among sexual minority youth, we considered that the sexual behavior of sexual minority individuals might differ from that of heterosexual individuals.

Finally, we identified 50 articles through the two search strategies, with 24 and 26 articles selected through the first and second strategies, respectively. This comprehensive approach enabled us to identify all relevant studies published between January 2000 and July 2020 that investigated the relationship between alcohol consumption and RSB.

Data Extraction

Two independent researchers (CS and TK) conducted data extraction and study quality assessment, with a third researcher (YY) providing oversight to ensure accuracy and consistency. Any discrepancies between the two researchers were resolved through discussion and consensus. A standardized form was used to extract the following information: first author, year of publication, study country, total sample size, participant characteristics (e.g., mean age, gender distribution), measurements of alcohol consumption, and RSBs. OR and 95% CI for each type of RSB were abstracted by three researchers using a structured coding sheet. To reduce potential confounding variables and observational bias, adjusted estimates that controlled for demographic, individual, peer, school, and community variables were extracted if available. If multiple models were presented, we selected estimates from the last model that controlled for the most variables. This meta-analysis adhered to the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Checklist, and the study selection flowchart was adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (22, 23).

Quality Assessment

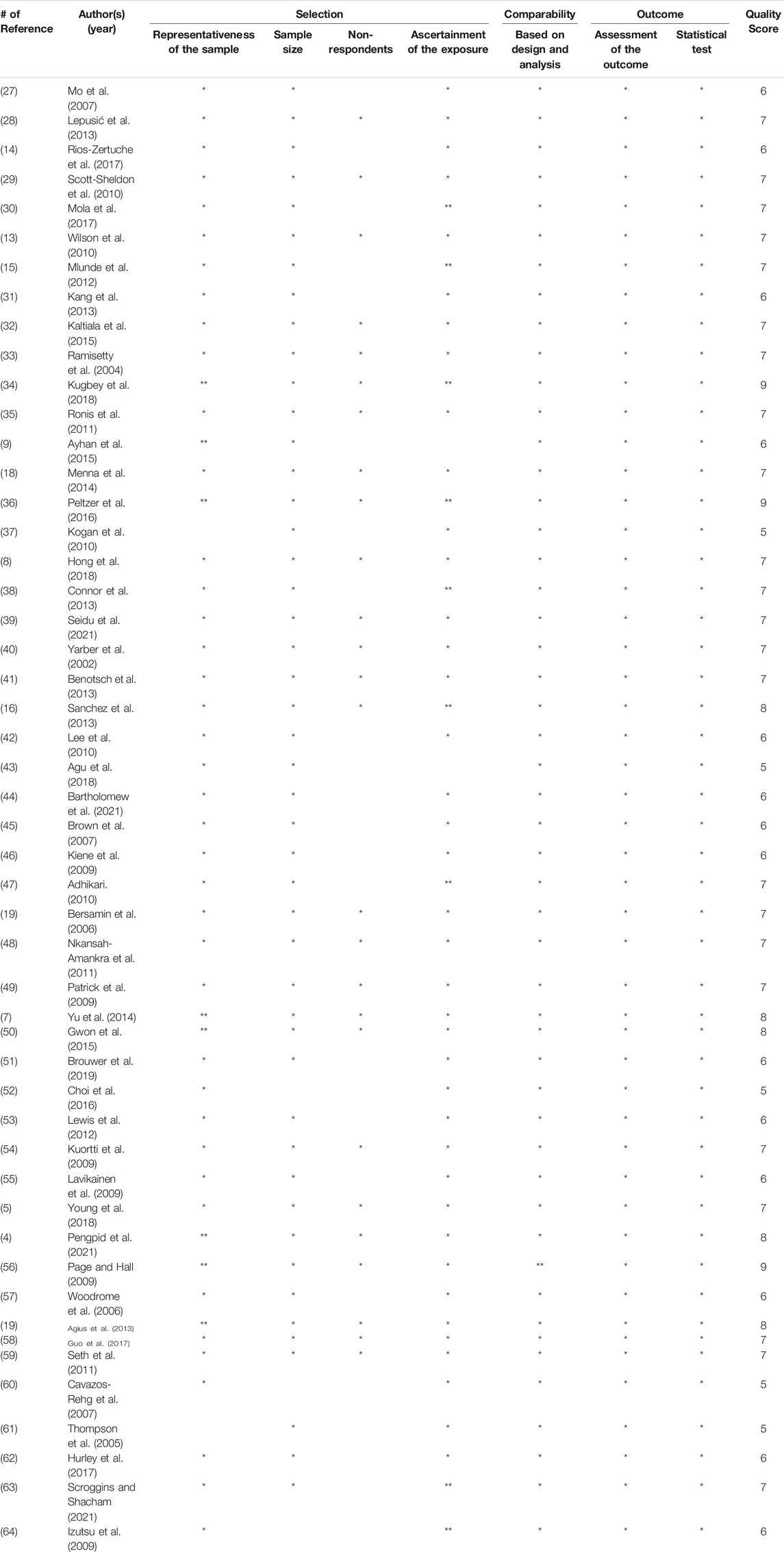

The methodological quality of the primary studies in this meta-analysis was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies (24). The assessment tool consisted of seven items: selection (representativeness of the sample, sample size, non-respondents, ascertainment of the exposure (risk factor), comparability, and outcome (assessment of the outcome and statistical test). For each item criterion, a maximum of five points for selection, two points for comparability, and three points for outcome could be given and then summed to a maximum of 10 points. Quality assessment results were evaluated as “good” if the NOS score was 7 points or higher, “fair” if the score was 5 points or higher or less than 7 points, and “poor” if the score was less than 5 points. Each of the two researchers independently conducted the quality assessment of the studies included in the analysis, and the final assessment scores were obtained after discussing a few discrepancy items.

Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) Version 3 software (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, United States). Odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs (early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners). The extent of heterogeneity among the primary studies was assessed using Cochrane’s Q test (reported with x2 and p values) and Higgins I2 value (25). An I2 value of up to 25% indicated low heterogeneity, 50% indicated moderate heterogeneity, and ≥75% indicated high heterogeneity (25). Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot, trim-fill analysis, and Egger’s regression test. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing each study and examining the effect size (26). The random effects model was used for the meta-analysis, and a meta-regression analysis was performed with sex as a control variable. The level of significance for all analyses in this study was determined using a two-tailed p value of <0.05 with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Characteristics of Primary Studies

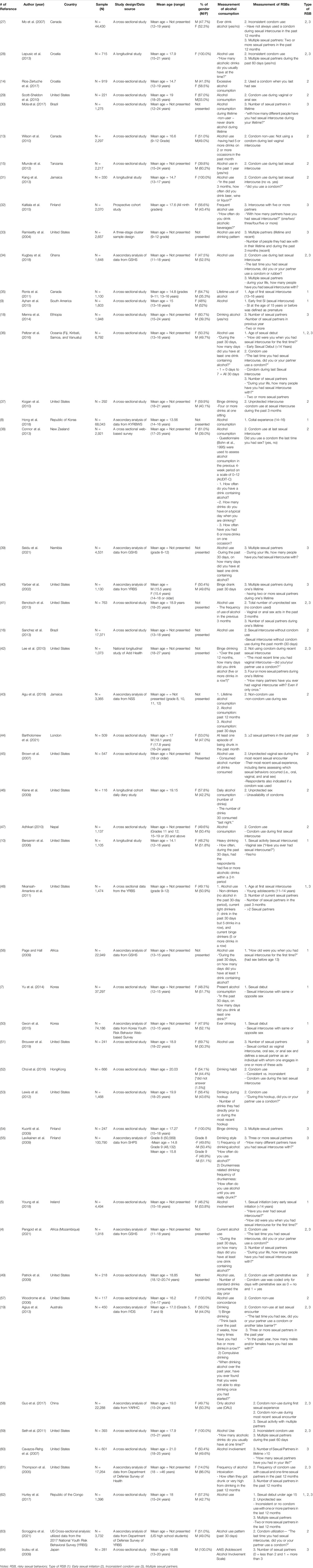

Fifty studies were included in the meta-analysis based on the selection criteria of this study and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) assessment (Table 1). These studies were published between 2002 and 2021, and among the included studies, most were published in 2009, 2013 (n = 6 studies), followed by 2010 (n = 5 studies), 2017 (n = 4 studies), 2018 (n = 4 studies), and 2021 (n = 4 studies). Most published studies were written in English (n = 47 studies), and three were written in Korean; among the 50 articles, most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 23 studies), and seven were conducted in Europe (Croatia, Finland, Ireland, and the United Kingdom) and Asia (South Korea, China, Hong Kong, and Japan).

TABLE 1. Characteristics of the included studies on the relationship between alcohol consumption and RSB (Worldwide, 2001–2021).

The number of participants in 50 studies was 442,909, with sample sizes ranging from 116 to 100,790; whereas others used large-scale data from the School Health Promotion Study (SHPS) in Finland or the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States (55, 63). SHPS is a nationally representative sample of adolescents born between 1987 and 1989, with 374 municipalities out of 448 participating in Finnish municipalities. The YRBS is weighted by respondents to be nationally representative data from the 2017 National YRBS cross-sectional data developed by the US CDC for US high school students (n = 3,732).

The overall mean age of the participants was 17.24 years, and most studies were conducted with both males and females (n = 34 studies). However, some studies focused on a specific sex, such only females (n = 5 studies) and only males (n = 1 study).

Exploring the characteristics of the responses used in the measurement of alcohol consumption, the most common response was a “yes” or “no” for alcohol drinking (n = 28 studies), and the measurement methods of alcohol use were different for each study, such as frequency of alcohol consumption (n = 6 studies), amount of alcohol consumption (glass) (n = 4 studies), alcohol involvement (n = 2 studies), drinking pattern (n = 2 studies), and others (n = 6 studies). Some studies used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) to assess alcohol consumption in the previous 4-week period on a scale of 0–12 (AUDIT-C) (38), while another study used the Adolescent Alcohol Involvement Scale (AAIS) tool (64).

Quality of the Included Studies

Based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale assessment, 31 articles were rated as “good” while the remaining studies were rated as “fair” in terms of methodological quality (Table 2).

Results of Meta-Analysis

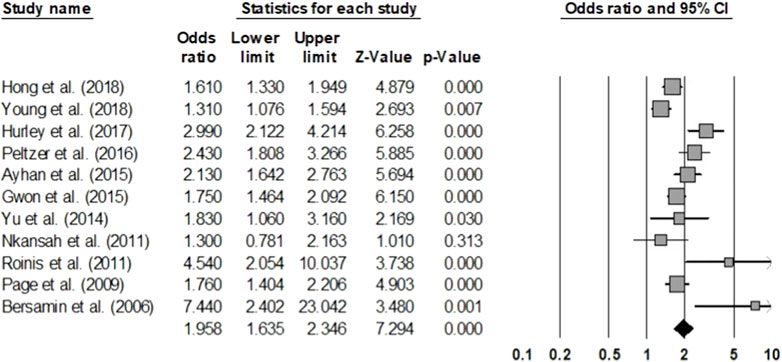

Early Sexual Initiation

After analyzing 11 articles studying early sexual initiation in adolescents, the incidence of sexual experience at an early age was found to be 1.958 times higher in the group that consumed alcohol compared to the group that did not (OR = 1.958, 95% CI = 1.635–2.346) (Figure 2). The analysis was based on 220,439 adolescents across the studies. The homogeneity test resulted in a Q statistic of 38.278 (p < 0.001) and an I2 statistic of 73.88%, demonstrating relatively high heterogeneity. Hence, the effect size was analyzed using a random-effects model.

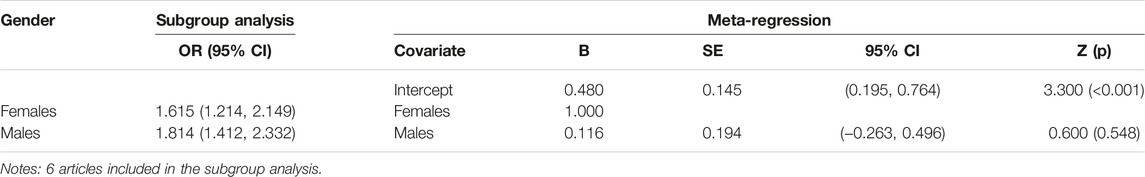

The publication bias test showed that some studies were omitted to the left of the mean effect size in the funnel plot, which seemed to be asymmetric, and Egger’s regression test showed a publication error (t = 2.272, p = 0.049). When the publication error is corrected using the trim-and-fill method, it is still statistically significant even if one more study is added (OR = 1.906, 95% CI = 1.581–2.298). Additionally, the sensitivity analysis showed that there was no substantial difference in the range of the mean effect size even after removing each individual article (1.854–2.056); and all were significant. To explain the heterogeneity of the effect size, a meta-regression analysis with sex as a moderating variable was conducted, indicating that it was statistically insignificant (Z = 0.600, p = 0.548) (Table 3).

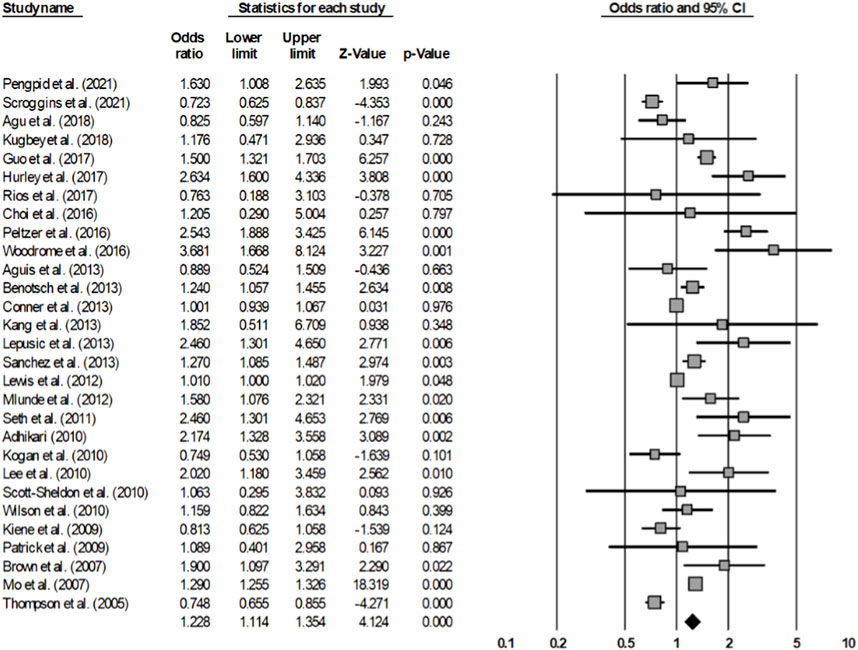

Inconsistent Condom Use

After analyzing 29 articles that investigated inconsistent condom use among adolescents and young adults, the rate of condom non-use during sexual intercourse was found to be 1.228 times higher in the group that consumed alcohol compared to the group that did not consume alcohol (OR = 1.228, 95% CI = 1.114–1.354) (Figure 3). The analysis included 137,064 individuals across the studies. The homogeneity test resulted in a Q statistic of 474.933 (p < 0.001), and an I2 statistic of 94.10%, demonstrating high heterogeneity. Hence, the effect size was analyzed using a random-effects model.

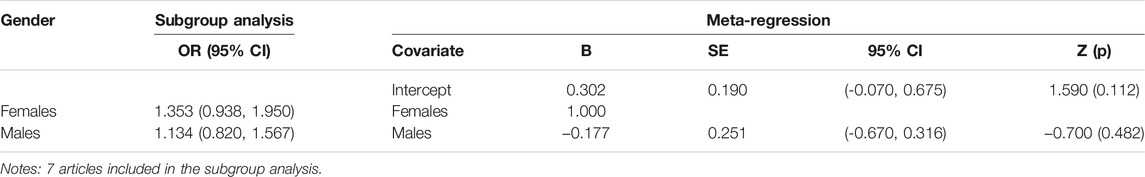

The publication bias test showed that some studies were omitted to the left direction of the mean effect size in the funnel plot, which seemed to be asymmetric; however, it can be determined that there was no publication error according to Egger’s regression test (t = 1.732, p = 0.095). Additionally, the sensitivity analysis showed that there was no substantial difference in the range of the mean effect size, even after removing each article (1.184–1.283); and all were significant. To explain the heterogeneity of the effect size, a meta-regression analysis with sex as a moderating variable was conducted, which indicated that it was statistically insignificant (Z = −0.700, p = 0.4817) (Table 4).

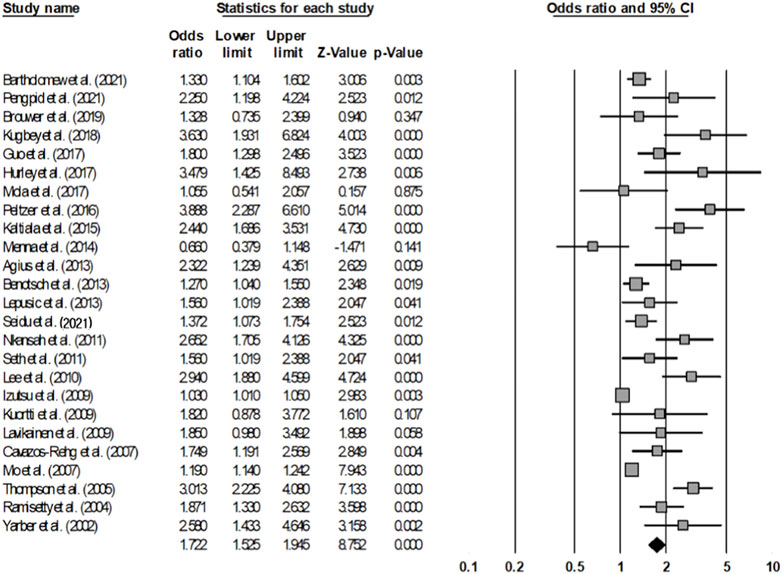

Multiple Sexual Partners

Upon analyzing 25 articles, based on a total of 216,884 adolescents and young adults, that studied multiple sexual partners, the rate of having multiple sexual partners was 1.722 times higher in the group that consumed alcohol than in the group that did not (OR = 1.722, 95% CI = 1.525–1.945) (Figure 4). The homogeneity test resulted in a Q statistic of 253.151 (p < 0.001) and an I2 statistic of 90.52%, demonstrating high heterogeneity. Hence, the effect size was analyzed using a random-effects model.

The publication bias test showed that some studies were omitted to the left direction of the mean effect size in the funnel plot, which seemed to be asymmetric, and there was a publication error according to Egger’s regression test (t = 6.518, p < 0.001). When the publication error is corrected using the trim-and-fill method, it can be seen that it is still statistically significant even if nine more studies are added (OR = 1.367, 95% CI = 1.224–1.527). In addition, the sensitivity analysis showed that there was no substantial difference in the range of the mean effect size even after removing each article (1.653–1.838); and all were significant.

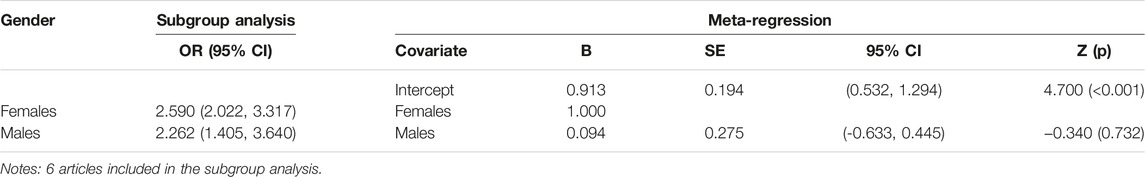

To explain the heterogeneity of the effect size, a meta-regression analysis with sex as a moderating variable was conducted, indicating that it was statistically insignificant (Z = −0.340, p = 0.732) (Table 5).

Discussion

This meta-analysis included 50 independent studies that investigated the relationship between alcohol consumption and RSBs in adolescents and young adults. The RSBs considered in this study were early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners. The odds ratio (OR) was used as the effect size measure, with OR = 1.958 for early sexual initiation, OR = 1.228 for inconsistent condom use, and OR = 1.722 for multiple sexual partners among adolescents and young adults who consumed alcohol, compared to those who did not. No sex-based differences were observed. These findings are consistent with the Alcohol Myopia Theory (65), which posits that alcohol consumption can impair cognitive processing and narrow individuals’ focus of attention rather than long-term goals or consequences, leading to a myopic view of the immediate environment and an over-reliance on cues that are immediately present, which may make individuals less likely to consider the potential consequences of their actions and more likely to engage in risky behaviors (66). By understanding the mechanisms underlying the association between alcohol consumption and RSBs, we can develop more effective prevention and intervention strategies to reduce the negative health outcomes associated with these behaviors.

The age of early sexual initiation among adolescents can vary within and between countries and cultures, but the mean age of sexual intercourse among sexually-experienced adolescents is typically between the ages of 14 and 15 (9, 10, 35). Some studies define early sexual experience as occurring at 14 years of age or younger (5, 36), but it is notable that the trend of sexual initiation age is rising in many countries. For example, a study conducted in the United States found that the proportion of adolescents who have had sexual intercourse before the age of 13 has declined over time from 10.2% in 1991% to 3.4% in 2017 (67). Similarly, a recent study on sub-Saharan Africa found that the age at first sexual intercourse among birth cohorts entering adulthood between 1985 and 2020 had increased over time, with the median age at first sex rising from 17.1 to 18.7 years for men and from 17.6 to 19.1 years for women (68).

The odds ratio of alcohol consumption and early sexual initiation was the highest at 1.958. This phenomenon of early alcohol consumption and risky behaviors seems to be particularly prominent in the United States, where the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) is 21 years old (69). Despite this, a significant number of high school students under the age of 21 still report drinking alcohol, with one study finding that 29% of high school students reported consuming alcohol (67). Mo et al (27) also reported that 43.4% of adolescents between the ages of 14 and 16 had consumed alcohol and were 1.13 times more likely to engage in early sexual initiation. Early alcohol consumption during adolescence can lead to other risky behaviors, such as smoking, substance abuse, and RSBs (17, 69). Thus, implementing policies and strategies to increase the age at which alcohol is initiated, and measures like designating the MLDA and requiring ID for alcohol purchases, could be effective in reducing alcohol consumption among young people. However, it is notable that further research is needed to better understand the complex relationship between alcohol consumption and risky behaviors among adolescents and young adults.

Of the 50 studies analyzed in the meta-analysis, 29 studies examined the relationship between inconsistent condom use and alcohol consumption among adolescents. The results showed that adolescents and young adults who drank were 1.228 times more likely to engage in inconsistent condom use during sexual intercourse that those who did not.

These findings are consistent with the Inhibition Conflict Theory, which suggests that alcohol consumption can lead to a conflict between an individual’s desires and their inhibitions, resulting in a failure to inhibit inappropriate or risky behaviors (70). Dermen and Cooper (70) provides further support for this theory, showing that the quantity of alcohol consumed was negatively associated with condom use only among high-conflict individuals. In sexual behavior, this conflict could result in a failure to use condoms consistently, despite knowledge of the potential risks associated with unprotected sex. Adolescents who consume alcohol may be more likely to prioritize their immediate desires over their long-term health and wellbeing, leading to a failure to use condoms consistently during sexual activity. By understanding the role of inhibition conflict and alcohol expectancy in the association between alcohol consumption and inconsistent condom use, we can develop more targeted prevention and intervention strategies to reduce the gap of desires and conflict.

Although the rate of sexual experience among adolescents aged 13–18 years is increasing, only 65.5% of adolescents who have experienced sexual intercourse reported using condoms for contraception, with 64.6% being male and 67.0% female (11). This indicates that male adolescents are more passive in the practice of contraception compared to female adolescents. However, it is notable that alcohol consumption has a negative impact on condom use during sexual intercourse. The rate of condom use during sexual intercourse is already low at 57.9%, and drops to 51.2% when alcohol is involved (16). RSBs without condom use result in burden and responsibility due to unintended pregnancy among female adolescents. The integrative model of behavioral prediction (71) suggests that female adolescents may find it difficult to ask their partners to use condoms due to the influence of perceived normative pressure, lack of self-efficacy, and perceived control skill (14). To increase condom use among adolescents and prevent unwanted pregnancies or STDs after risky sexual intercourse, sex education should be provided in elementary schools regarding the consequences of not using condoms and how to use them correctly. Such education should be delivered not only within the school system but also at community centers and related institutions. Condoms should be universalized to enable youth to easily purchase them at pharmacies and convenience stores. Additionally, various programs should be implemented to strengthen communication, self-efficacy, and control skills so that female adolescents can confidently demand the use of condoms from their male partners.

The meta-analysis that examined the relationship between alcohol consumption and having multiple sexual partners included 25 studies and found that the risk of having two or more sexual partners was approximately 1.722 times higher for adolescents and young adults who drank alcohol. Among studies that examined the number of sexual partners by sex, Kugbey et al (34) and Mo et al (27) found that 61.1% of male adolescents had multiple sexual partners. However, some studies have reported no significant sex-related differences in the number of sexual partners (27). This study also found no significant sex-related differences depending on sex (male and female). The age at which alcohol consumption is initiated also affects the number of sexual partners. For example, a study found that females and males who began drinking alcohol at the age of 15 had a higher likelihood of having multiple sexual partners compared to those who began drinking at a later age (72). Such risky sexual behavior may expose adolescents to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) through sexual contact with strangers. Therefore, it is important to educate adolescents and young adults on the dangers of having multiple sexual partners while drinking alcohol due to precocious puberty and open sexual culture. This could be accomplished through comprehensive sex education that covers the risks of unprotected sex, the importance of safe sex practices, and strategies for avoiding risky situations. It is also crucial to promote responsible drinking behaviors and discourage underage drinking, as early initiation of alcohol use is associated with a higher risk of engaging in risky sexual behavior. The Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction (73) can be applied to understand the relationship between the intention to engage in RSBs and the actual practice of such behavior. This model may help in the development of a behavioral strategy to promote healthy sexual behavior. As alcohol negatively impacts all forms of RSBs, intervention for controlling adolescent drinking is necessary. However, since the level of risk associated with alcohol consumption varies depending on individual characteristics such as age and gender, it is difficult to apply the same guidelines for developing and implementing alcohol control programs from adolescents to young adults. Therefore, we propose developing intervention guidelines for each age group, considering factors such as age, gender, and educational methods, to develop the most effective guidelines. We also suggest using a tool called AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) to screen and assess risky drinkers among adolescents and young adults and provide different types of intervention based on their risk zone: alcohol education for low-risk drinkers, simple advice for hazardous drinkers, brief counselling for harmful drinkers, and referral for probable dependent drinkers (32).

Limitations and Strengths

The study has several limitations, and we suggest some areas for future research. Firstly, the study did not take into account the frequency and amount of alcohol consumption, which varied among adolescents and young adults in each study. Additionally, the definition of variables such as the number of sexual partners and condom use varied across studies, with some studies measuring over a lifetime, and others measuring within a certain time frame (e.g., the last 60 days or the past 12 months). Therefore, we suggest that future meta-analyses should consider these variations in measurement when examining the relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sexual behaviors. Secondly, although the results indicate a positive association between alcohol consumption and RSBs in this population, it is notable that this association does not necessarily imply causality, as other factors may contribute to both behaviors. To address this limitation and better understand the causal relationship between alcohol consumption and RSBs, we recommend further research using longitudinal cohort studies or experimental designs. By following adolescents and young adults over time and controlling for potential confounding variables, these types of studies could help to establish the temporal sequence of alcohol consumption and RSBs and provide stronger evidence for causality. Finally, we only focused on three RSBs: early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple partners. However, there are other RSBs that can be influenced by alcohol consumption, such as casual sex, sex against the will, and sexual violence. Previous studies have suggested that alcohol can impair judgment and decision-making, increase sexual arousal and desire, and reduce inhibitions and self-control (74, 75). These effects can lead to engaging in sex with unfamiliar or untrusted partners, having unwanted or coerced sex, or being involved in sexual aggression or assault (76). Future research should examine how alcohol consumption affects these other RSBs among adolescents and young adults.

Despite these limitations, this study had several strengths. First, 20,000 articles were screened for studies on alcohol use and RSBs that reported odds ratios using two search strategies, and a large number of articles were comprehensively meta-analyzed. Three types of RSBs were analyzed to provide fundamental data for developing and implementing specific programs by comparing and discussing the risks of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults in early sexual initiation, which leads to inconsistent condom use and multiple sexual partners.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis highlights the significant association between alcohol consumption and early sexual initiation, inconsistent condom use, and multiple sexual partners among adolescents and young adults. The findings suggest that alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults may lead to exposure to unwanted pregnancy and STDs. Therefore, preventive interventions such as education and monitoring to prevent alcohol consumption and increasing the age criteria for drinking alcohol should be implemented. School- and community-based preventive interventions are required, such as education and monitoring to prevent alcohol consumption, and the age criteria for drinking alcohol in each country should be increased. Parents and guardians can provide guidance and support to help their children make healthy choices and avoid risky behaviors. Healthcare providers can also play an important role in preventing alcohol use among adolescents and young adults by screening for alcohol use, providing education on the harmful effects of alcohol, and referring adolescents and young adults to appropriate resources for prevention and treatment. Overall, it is crucial to raise awareness about the risks of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults and implement effective prevention measures to promote healthy behaviors and prevent the negative consequences of alcohol use.

Author Contributions

YY conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. H-SC participated in the design and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A03047080).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bonnie, RJ, Cook, PJ, Cushing, JA, Grube, JW, Halpern-Felsher, BL, Hansen, WB, et al. Reducing Underage Drinking; a Collective Responsibility. In: Commiitte on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (2004). 58–9P.

2.WHO. Alcohol (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/alcohol#tab=tab_1 (Accessed on August 24, 2022).

3.WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 (2018). Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf (Accessed on March 7, 2023).

4. Pengpid, S, and Peltzer, K. Sexual Risk Behaviour and its Correlates Among Adolescents in Mozambique: Results from a National School Survey in 2015. SAHARA-J: Soc Aspects HIV/AIDS (2021) 18(1):26–32. doi:10.1080/17290376.2020.1858947

5. Young, H, Burke, L, and Gabhainn, SN. Sexual intercourse, Age of Initiation and Contraception Among Adolescents in Ireland: Findings from the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Ireland Study. BMC Public Health (2018) 18:1–17. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5217-z

6. Cook, RL, Comer, DM, Wiesenfeld, HC, Chang, C-CH, Tarter, R, Lave, JR, et al. Alcohol and Drug Use and Related Disorders: An Underrecognized Health Issue Among Adolescents and Young Adults Attending Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinics. Sex Transm Dis (2006) 33(9):565–70. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000206422.40319.54

7. Yu, J-O, Kim, H-H, and Kim, J-S. Factors Associated with Sexual Debut Among Korean Middle School Students. Child Health Nurs Res (2014) 20(3):159–67. doi:10.4094/chnr.2014.20.3.159

8. Hong, SW, Suh, YS, and Kim, DH. The Risk Factors of Sexual Behavior Among Middle School Students in South Korea. Int J Sex Health (2018) 30(1):72–80. doi:10.1080/19317611.2018.1429513

9. Ayhan, G, Martin, L, Levy-Loeb, M, Thomas, S, Euzet, G, Van Melle, A, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Early Onset of Sexual intercourse in a Random Sample of a Multiethnic Adolescent Population in French Guiana. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-medical Aspects AIDS/HIV (2015) 27(8):1025–30. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1020282

10. Bersamin, MM, Walker, S, Fisher, DA, and Grube, JW. Correlates of Oral Sex and Vaginal Intercourse in Early and Middle Adolescence. J Res Adolesc (2006) 16(1):59–68. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00120.x

11.Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Report of 2021 Adolescent Health Behavior Survey. Cheongju: KDCA (2021). 66–71. Available at: https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/home.jsp (Accessed on Feb 9, 2022).

12. Pettifor, A, Brien, KO, Macphail, C, Miller, WC, and Rees, H. Early Coital Debut and Associated HIV Risk Factors Among Young Women and Men in South Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health (2009) 35(2):82–90. doi:10.1363/ifpp.35.082.09

13. Wilson, K, Asbridge, M, Kisely, S, and Langille, D. Associations of Risk of Depression with Sexual Risk Taking Among Adolescents in Nova Scotia High Schools. Can J Psychiatry (2010) 55(9):577–85. doi:10.1177/070674371005500906

14. Rios-Zertuche, D, Cuchilla, J, Zúñiga-Brenes, P, Hernández, B, Jara, P, Mokdad, AH, et al. Alcohol Abuse and Other Factors Associated with Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Adolescent Students from the Poorest Areas in Costa Rica. Int J Public Health (2017) 62(2):271–82. doi:10.1007/s00038-016-0859-z

15. Mlunde, LB, Poudel, KC, Sunguya, BF, Mbwambo, JK, Yasuoka, J, Otsuka, K, et al. A Call for Parental Monitoring to Improve Condom Use Among Secondary School Students in Dares Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health (2012) 12(1):1061–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1061

16. Sanchez, ZM, Nappo, SA, Cruz, JI, Carlini, EA, Carlini, CM, and Martins, SS. Sexual Behavior Among High School Students in Brazil: Alcohol Consumption and Legal and Illegal Drug Use Associated with Unprotected Sex. Clinics (2013) 68:489–94. doi:10.6061/clinics/2013(04)09

17.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism(NIAAA). Alcohol Intervention for Young Adults (2022). Available at: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-interventions-young-adults (Accessed on Sep 09, 2022).

18. Menna, T, Ali, A, and Worku, A. Prevalence of “HIV/AIDS Related” Parental Death and its Association with Sexual Behavior of Secondary School Youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a Cross Sectional Study. BMC Public Health (2014) 14(1):1120–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1120

19. Agius, P, Taft, A, Hemphill, S, Toumbourou, J, and McMorris, B. Excessive Alcohol Use and its Association with Risky Sexual Behaviour: a Cross-sectional Analysis of Data from Victorian Secondary School Students. Aust N Z J Public Health (2013) 37(1):76–82. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12014

20. Tapert, SE, Aarons, GA, Sedlar, GR, and Brown, SA. Adolescent Substance Use and Sexual Risk-Taking Behavior. Adolesc Health (2000) 28(3):181–9. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00169-5

21. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DGPRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Plos Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

22. Liberati, A, Altman, DG, Tetzlaff, J, Mulrow, C, Gøtzsche, PC, Ioannidis, JPA, et al. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies that Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ (2009) 339:b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

23. Stroup, DF, Berlin, JA, Morton, SC, Olkin, I, Williamson, GD, Rennie, D, et al. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: a Proposal for Reporting. Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. JAMA (2000) 283(15):2008–12. doi:10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

24. Herzog, R, Álvarez-Pasquin, M, Díaz, C, Del Barrio, JL, Estrada, JM, and Gil, Á. Are Healthcare Workers’ Intentions to Vaccinate Related to Their Knowledge, Beliefs and Attitudes? A Systematic Review. BMC public health (2013) 13(1):154–17. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-154

25. Hwang, SD, and Shim, SR. Meta-analysis: From a forest Plot to a Network Meta-Analysis. Seoul: Hannarae Publishing Company (2018). p. 128–34.

26. Egger, M, Smith, GD, Schneider, M, and Minder, C. Bias in Meta-Analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test. Br Med J (1997) 315(7109):629–34. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

27. Mo, F, Wong, T, and Merrick, J. Adolescent Lifestyle, Sexual Behavior and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) in Canada. Int J Disabil Hum Dev (2007) 6(1):53–60. doi:10.1515/ijdhd.2007.6.1.53

28. Lepušić, D, and Radović-Radovčić, S. Alcohol–a Predictor of Risky Sexual Behavior Among Female Adolescents. Acta Clin Croat (2013) 52(1):3–8.

29. Scott-Sheldon, LAJ, Carey, MP, and Carey, KB. Alcohol and Risky Sexual Behavior Among Heavy Drinking College Students. AIDS Behav (2010) 14(4):845–53. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9

30. Mola, R, Araújo, RC, Oliveira, JVB, Cunha, SB, Souza, GF, Ribeiro, LP, et al. Association between the Number of Sexual Partners and Alcohol Consumption Among Schoolchildren. J Pediatr (2017) 93:192–9. doi:10.1016/j.jped.2016.05.003

31. Kang, SY, Hutchinson, MK, and Waldron, N. Characteristics Related to Sexual Experience and Condom Use Among Jamaican Female Adolescents. J Health Care Poor Underserved (2013) 24(1):220–32. doi:10.1353/hpu.2013.0023

32. Babor, TF, Higgins-Biddle, JC, Saunders, JB, and Monteiro, MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2001).

33. Ramisetty-Mikler, S, Caetano, R, Goebert, D, and Nishimura, S. Ethnic Variation in Drinking, Drug Use, and Sexual Behavior Among Adolescents in Hawaii. J Sch Health (2004) 74(1):16–22. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06596.x

34. Kugbey, N, Ayanore, MA, Amu, H, Asante, KO, and Adam, A. International Note: Analysis of Risk and Protective Factors for Risky Sexual Behaviours Among School-Aged Adolescents. J adolescence (2018) 68:66–9. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.013

35. Ronis, ST, and O'Sullivan, LF. A Longitudinal Analysis of Predictors of Male and Female Adolescents' Transitions to Intimate Sexual Behavior. J Adolesc Health (2011) 49(3):321–3. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.010

36. Peltzer, K, and Pengpid, S. Risk and Protective Factors Affecting Sexual Risk Behavior Among School-Aged Adolescents in Fiji, Kiribati, Samoa, and Vanuatu. Asia Pac J Public Health (2016) 28(5):404–15. doi:10.1177/1010539516650725

37. Kogan, SM, Brody, GH, Chen, Y-f, Grange, CM, Slater, LM, and DiClemente, RJ. Risk and Protective Factors for Unprotected intercourse Among Rural African American Young Adults. Public Health Rep (2010) 125(5):709–17. doi:10.1177/003335491012500513

38. Connor, J, Psutka, R, Cousins, K, Gray, A, and Kypri, K. Risky Drinking, Risky Sex: a National Study of New Zealand university Students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2013) 37(11):1971–8. doi:10.1111/acer.12175

39. Seidu, AA, Ahinkorah, BO, Ameyaw, EK, Darteh, EKM, Budu, E, Iddrisu, H, et al. Risky Sexual Behaviours Among School-Aged Adolescents in Namibia: Secondary Data Analyses of the 2013 Global School-Based Health Survey. J Public Health (2021) 29:451–61. doi:10.1007/s10389-019-01140-x

40. Yarber, WL, Milhausen, R, Crosby, RA, and DiClemente, RJ. Selected Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Two or More Lifetime Sexual intercourse Partners and Non-condom Use during Last Coitus Among US Rural High School Students. Am J Health Education (2002) 33(4):206–15. doi:10.1080/19325037.2002.10603509

41. Benotsch, EG, Snipes, DJ, Martin, AM, and Bull, SS. Sexting, Substance Use, and Sexual Risk Behavior in Young Adults. J Adolesc Health (2013) 52(3):307–13. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.011

42. Lee, J, and Hahm, HC. Acculturation and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Latina Adolescents Transitioning to Young Adulthood. J Youth Adolescence (2010) 39(4):414–27. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9495-8

43. Agu, CF, Oshi, DC, Abel, WD, Rae, T, Oshi, SN, Ricketts-Roomes, T, et al. Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Risk Behaviour Among Jamaican Adolescents. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev (2018) 19(1):1–6. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.S1.1

44. Bartholomew, R, Kerry-Barnard, S, Beckley-Hoelscher, N, Phillips, R, Reid, F, Fleming, C, et al. Alcohol Use, Cigarette Smoking, Vaping and Number of Sexual Partners: A Cross-sectional Study of Sexually Active, Ethnically Diverse, Inner City Adolescents. Health Expect (2021) 24(3):1009–14. doi:10.1111/hex.13248

45. Brown, JL, and Vanable, PA. Alcohol Use, Partner Type, and Risky Sexual Behavior Among College Students: Findings from an Event-Level Study. Addict behaviors (2007) 32(12):2940–52. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011

46. Kiene, SM, Barta, WD, Tennen, H, and Armeli, S. Alcohol, Helping Young Adults to Have Unprotected Sex with Casual Partners: Findings from a Daily Diary Study of Alcohol Use and Sexual Behavior. J Adolesc Health (2009) 44(1):73–80. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008

47. Adhikari, R. Are Nepali Students at Risk of HIV? A Cross-Sectional Study of Condom Use at First Sexual intercourse Among College Students in Kathmandu. J Int AIDS Soc (2010) 13(1):7. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-13-7

48. Nkansah-Amankra, S, Diedhiou, A, Agbanu, HL, Harrod, C, and Dhawan, A. Correlates of Sexual Risk Behaviors Among High School Students in Colorado: Analysis and Implications for School-Based HIV/AIDS Programs. Matern Child Health J (2011) 15(6):730–41. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0634-3

49. Patrick, ME, and Maggs, JL. Does Drinking lead to Sex? Daily Alcohol–Sex Behaviors and Expectancies Among College Students. Psychol Addict behaviors (2009) 23(3):472–81. doi:10.1037/a0016097

50. Gwon, SH, and Lee, CY. Factors that Influence Sexual intercourse Among Middle School Students: Using Data from the 8th (2012) Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey. J Korean Acad Nurs (2015) 45(1):76–83. doi:10.4040/jkan.2015.45.1.76

51. Brouwer, AF, Delinger, RL, Eisenberg, MC, Campredon, LP, Walline, HM, Carey, TE, et al. HPV Vaccination Has Not Increased Sexual Activity or Accelerated Sexual Debut in a College-Aged Cohort of Men and Women. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):821–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7134-1

52. Choi, EP-H, Wong, JY-H, Lo, HH-M, Wong, W, Chio, JH-M, and Fong, DY-T. The Impacts of Using Smartphone Dating Applications on Sexual Risk Behaviours in College Students in Hong Kong. PLoS One (2016) 11(11):e0165394–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165394

53. Lewis, MA, Granato, H, Blayney, JA, Lostutter, TW, and Kilmer, JR. Predictors of Hooking up Sexual Behaviors and Emotional Reactions Among US College Students. Arch Sex Behav (2012) 41(5):1219–29. doi:10.10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2

54. Kuortti, M, and Kosunen, E. Risk-taking Behaviour Is More Frequent in Teenage Girls with Multiple Sexual Partners. Scand J Prim Health Care (2009) 27(1):47–52. doi:10.1080/02813430802691933

55. Lavikainen, HM, Lintonen, T, and Kosunen, E. Sexual Behavior and Drinking Style Among Teenagers: a Population-Based Study in Finland. Health Promot Int (2009) 24(2):108–19. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap007

56. Page, RM, and Hall, CP. Psychosocial Distress and Alcohol Use as Factors in Adolescent Sexual Behavior Among Sub-Saharan Africa Adolescents. School Health (2009) 79(8):369–79. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00423.x

57. Woodrome, SE, Zimet, GD, Orr, DP, and Fortenberry, JD. Dyadic Alcohol Use and Relationship Quality as Predictors of Condom Non-use Among Adolescent Females. J Adolesc Health (2006) 38(3):305–6. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.018

58. Guo, C, Wen, X, Li, N, Wang, Z, Chen, G, and Zheng, X. Is Cigarette and Alcohol Use Associated with High-Risk Sexual Behaviors Among Youth in China? J Sex Med (2017) 14(5):659–65. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.03.249

59. Seth, P, Sales, JM, DiClemente, RJ, Wingood, GM, Rose, E, and Patel, SN. Longitudinal Examination of Alcohol Use: a Predictor of Risky Sexual Behavior and Trichomonas Vaginalis Among African-American Female Adolescents. Sex Transm Dis (2011) 38(2):96–101. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f07abe

60. Cavazos-Rehg, PA, Spitznagel, EL, Bucholz, KK, Norberg, K, Reich, W, Nurnberger, J, et al. The Relationship between Alcohol Problems and Dependence, Conduct Problems and Diagnosis, and Number of Sex Partners in a Sample of Young Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2007) 31(12):2046–52. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00537.x

61. Thompson, JC, Kao, TC, and Thomas, RJ. The Relationship between Alcohol Use and Risk-Taking Sexual Behaviors in a Large Behavioral Study. Prev Med (2005) 41(1):247–52. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.008

62. Hurley, EA, Brahmbhatt, H, Kayembe, PK, Busangu, M-AF, Mabiala, M-U, and Kerrigan, D. The Role of Alcohol Expectancies in Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J Adolesc Health (2017) 60(1):79–86. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.023

63. Scroggins, S, and Shacham, E. What a Difference a Drink Makes: Determining Associations between Alcohol-Use Patterns and Condom Utilization Among Adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol (2021) 56(1):34–7. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agaa032

64. Izutsu, T, Tsutsumi, A, and Matsumoto, T. Association between Sexual Risk Behaviors and Drug and Alcohol Use Among Young People with Delinquent Behaviors. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi= Jpn J Alcohol Stud Drug Dependence (2009) 44(5):547–53.

65. Griffin, JA, Renée Umstattd, M, and Usdan, SL. Alcohol Use and High-Risk Sexual Behavior Among Collegiate Women: a Review of Research on Alcohol Myopia Theory. Am Coll Health (2010) 58(6):523–32. doi:10.1080/07448481003621718

66. Cooper, ML. Alcohol Use and Risky Sexual Behavior Among College Students and Youth: Evaluating the Evidence. Stud Alcohol (2002)(14) 101–17. doi:10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101

67. Kann, L, McManus, T, Harris, WA, Shanklin, SL, Flint, KH, Hawkins, J, et al. Youth Risk Behavior surveillance-United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ (2018) 67(8):1–114. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1

68. Nguyen, VK, Eaton, JW, Devi, AP, Poonsukkho, P, Sangvichien, E, Tran, TN, et al. Eumitrins F-H: Three New Xanthone Dimers from the Lichen Usnea Baileyi and Their Biological Activities. BMC Public Health (2022) 22(1):1–11. doi:10.1080/14786419.2021.2023143

69.CDC. Age 21 Minimum Legal Drinking Age (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/minimum-legal-drinking-age.htm (Accessed on Sep 1, 2022).

70. Dermen, KH, and Cooper, ML. Inhibition Conflict and Alcohol Expectancy as Moderators of Alcohol's Relationship to Condom Use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol (2000) 8(2):198–206. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.8.2.198

71. Fishbein, M, and Yzer, MC. Using Theory to Design Effective Health Behavior Interventions. Commun Theor (2003) 13(2):164–83. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x

72. Kaltiala-Heino, R, Fröjd, S, and Marttunen, M. Depression, Conduct Disorder, Smoking and Alcohol Use as Predictors of Sexual Activity in Middle Adolescence: a Longitudinal Study. Health Psychol Behav Med (2015) 3(1):25–39. doi:10.1080/21642850.2014.996887

73. Ajzen, I, and Albarracín, D. Predicting and Changing Behavior: A Reasoned Action Approach. In: I Ajzen, D Albarracín, and R Hornik, editors. Prediction and Change of Health Behavior: Applying the Reasoned Action Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (2007). 3–21.

74. Lorenz, K, and Ullman, SE. Alcohol and Sexual Assault Victimization: Research Findings and Future Directions. Aggression Violent Behav (2016) 31:82–94. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2016.08.001

75. George, WH, and Stoner, SA. Understanding Acute Alcohol Effects on Sexual Behavior. Annu Rev sex Res (2000) 11(1):92–124. doi:10.1080/10532528.2000.10559785

76.CDC. Substance Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Youth (2019). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/substance-use/dash-substance-use-fact-sheet.htm (Accessed on Mar 7, 2023).

Keywords: meta-analysis, risky sexual behavior, alcohol consumption, adolescent, young adult

Citation: Cho H-S and Yang Y (2023) Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Risky Sexual Behaviors Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Int J Public Health 68:1605669. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605669

Received: 08 December 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2023;

Published: 19 April 2023.

Edited by:

Gabriel Gulis, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkCopyright © 2023 Cho and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Youngran Yang, eW91bmdyYW4xM0BqYm51LmFjLmty

This Review is part of the IJPH Special Issue “Public Health and Primary Care, is 1+1=1?”

Hyang-Soon Cho1

Hyang-Soon Cho1 Youngran Yang

Youngran Yang