- 1Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Al-Balqa Applied University, Al-Salt, Jordan

- 2Department of Public Health, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

- 3Department of Maternal and Child Health Nursing, School of Nursing, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

- 4Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

- 5Department of Physiology and Biochemistry, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

- 6Faculty of Nursing, Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan

- 7Department of Health Management and Policy, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Objectives: To compare obstetric and neonatal characteristics and birth outcomes between Syrian refugees and native women in Jordan.

Methods: We used the Jordan Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths Surveillance System to extract sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the mothers and birth characteristics of newborns. Multivariate analysis was used to compare the characteristics of 26,139 Jordanian women (27,468 births) and 3,453 Syrian women refugees (3,638 births) who gave birth in five referral hospitals (May 2019 and December 2020).

Results: The proportions of low birthweight (14.1% vs. 11.8%, p < 0.001) and small for gestational age (12.0% vs. 10.0%, p < 0.001) newborns were significantly higher for those born to Syrian women compared to those born to Jordanian women. The stillbirth rate (15.1 vs. 9.9 per 1,000 births, p = 0.003), the neonatal death rate (21.2 vs. 13.2 per 1,000 live births, p < 0.001), and perinatal death rate (21.2 vs. 13.2 per 1,000 births, p < 0.001) were significantly higher for the Syrian births. After adjusting for sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of women, only perinatal death was statistically significantly higher among Syrian babies compared to Jordanian babies (OR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.7, p = 0.035).

Conclusion: Syrian refugee mothers had a significantly higher risk of adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes including higher rate of perinatal death compared to Jordanian women.

Introduction

Forced migration occurs globally for various reasons, including wars and political conflicts, economic circumstances, or environmental crises [1]. Women refugees of all nationalities are a particularly vulnerable group of displaced people. Having a higher reported prevalence of adverse maternal-neonatal outcomes than native women [2, 3] makes them a unique population in host communities in terms of needed humanitarian and healthcare services. Stillbirths, delayed arrival at the hospital for birth [4, 5], inappropriate weight for gestational age [2], low birthweight infants [6], and higher rates of neonatal intensive treatments for neonatal comorbidities [2] are a few adverse pregnancy outcomes that are commonly reported among women refugees. However, contemporary research and knowledge on women refugees’ health during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes is limited in the international literature. Therefore, further understanding of how their health is compared to non-refugee counterparts is needed [3].

Since March 2011, Syria has been in a state of political instability that has resulted in about 13.5 million Syrians being forcibly displaced to escape the war, out of which 6.8 million sought refuge in their country [7]. The neighbouring country of Jordan has been the host of more than one million Syrian refugees [8], of which only 673,957 have registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as of February 2022 [9]. Women and girls constitute 49.6% of all registered refugees in Jordan, and 30% of them are above the age of 12 years [9]. Further, reports indicate that the majority (>85%) of registered Syrian refugees live outside camps, in urban, peri-urban, or rural regions of Jordan [9]. According to recent assessments of the needs of refugees for financial and non-financial services [10, 11], more than 86% of Syrian refugees live under the Jordanian poverty line [11] despite the substantial response by government and humanitarian partners.

In Jordan, healthcare services, including pregnancy and delivery services, are available to all registered refugees from all nationalities at the non-insured Jordanian rate at public health centres and governmental hospitals [12]. However, because most Syrian refugees are not insured and must pay health-related fees for hospitals and clinics, Syrian refugees identified cost as the main barrier to healthcare access [13]. The UNHCR supports healthcare services for all refugees. However, research has shown that Syrian women refugees in Jordan continue to have significant unmet needs and barriers to access, utilisation, and implementation of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) in comparison to their host community counterparts [14, 15].

There is limited research assessing the reproductive health status and service delivery among Syrian refugees in Jordan [14]. Currently, there is little understanding of the risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes among Syrian women refugees in Jordan and the extent to which disparities exist regarding pregnancy outcomes. The adverse maternal and neonatal pregnancy outcomes and disparities need to be addressed first, and their contributing factors should be systematically investigated to improve the maternal healthcare utilisation and health services provided to Syrian women refugees.

The Jordan Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths Surveillance System (JSANDS) is an electronically secure surveillance system to register and disseminate reliable, comprehensive, individual-level data on stillbirths and neonatal deaths, the causes and the risk factors most commonly associated with perinatal mortality in Jordan [16–18]. The system record events for women prospectively after giving their births. The surveillance system automatically and accurately transfers the data on births, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths from five maternity hospitals to the Ministry of Health [16]. These hospitals are among the most significant and primary referral hospitals in Jordan that cover most births and deaths in all regions in the north, east, and south of Jordan. Khader, Alyahya [16] examined the JSANDS attributes, including its data quality and sensitivity. The system users rated the usefulness of JSANDS as excellent (percentage score = 85.6%). The overall acceptability (percentage score = 82.3%), flexibility (percentage score = 80.2%), stability (percentage score = 80.0%), and representativeness (percentage score = 86.6%) were also rated excellent. All variables in JSANDS had complete data with no missing values for clinical variables because these data are entered by nurses who were trained to enter data completely and because the system has automated quality checks. The overall simplicity was scored well (percentage score = 75.4%) [16].

The purpose of this study is to explore the adverse birth outcomes among Syrian women refugees and Jordanian women using data from the JSANDS. Specifically, in this study we identified disparities of the obstetric and neonatal characteristics and birth outcomes between Syrian and Jordanian women, and explored the factors determining adverse neonatal birth outcomes among Syrian women in Jordan.

Methods

Study Design

All births, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths in five hospitals from May 2019 to December 2020 were completely registered in JSANDS. The five hospitals, including one university teaching hospital, three public hospitals, and one private hospital, were selected for pilot testing of the JSANDS. The criteria for the selection of hospitals and JSANDS usability and functionality were described in previous studies [17, 19, 20]. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of Jordanian and Syrian women and their birth outcomes were retrieved from JSANDS and compared.

Variables

The extracted data consisted of sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the mothers, including age, education, employment status, income, gestational age, mode of delivery, and multiplicity. Other data included information on neonatal characteristics and birth outcomes, such as birthweight and status (born alive, stillbirth, and neonatal death).

Definitions

Birthweight was categorised into low (1,500 g–<2,500 g), very low (<1,500 g–1,000 g), and extremely low birthweight (<1,000 g) [21]. The gestational age was categorised into extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28–<32 weeks), and moderate or late preterm (32–<37 completed weeks of gestation) [22]. The definition of stillbirths and neonatal deaths used in this study was based on the international standards set by the World Health Organization [23]. Neonatal mortality was defined as any death that happened at or after 24 gestational weeks within the first 28 days of life. The neonatal mortality rate was calculated as the number of neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births (LB). Stillbirth was defined as any foetal death that occurred at or after 24 gestational weeks. Stillbirths were categorised as antepartum (deaths occurring prior to labour) and intrapartum (deaths that occur after the onset of labour but prior to birth). The stillbirth rate was calculated as the number of stillbirths per 1,000 total births. The foetal weight percentile was determined based on birthweight and foetal age. Foetal growth was categorised as small for gestational age (SGA) if <10th percentile, appropriate for gestation if between 10th and 90th percentile, or large for gestation if >90th percentile.

Ethical Considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was ethically approved by Jordan University of Science and Technology Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Ethical approval number 20170033) to conduct the study at King Abdulla University Hospital, Jordan Ministry of Health Review Committee to conduct the study in the three public hospitals, and the Irbid Speciality Hospital (private hospital) Ethical Committee. Permission from the Ministry of Health was received to access the data and use it for research purposes. To ensure the confidentiality of the data, the data were exported without identifying information, such as the name or phone number.

Data Analysis

Data were described and analysed using IBM SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Percentages were used for categorical data. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of Jordanian and Syrian women and their birth outcomes were compared and analysed using the Chi-square test. Multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression was performed to compare the birth outcomes of Jordanian and Syrian women after adjusting for women’s characteristics. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Women’s Characteristics

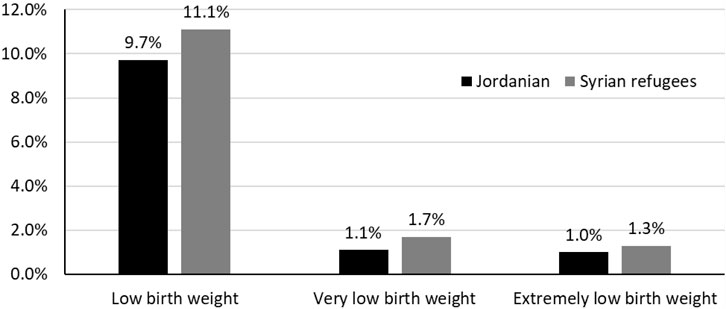

This study included a total of 26,139 Jordanian women (27,468 births) and 3,453 Syrian women refugees (3,638 births). Of the total Jordanian and Syrian births, 271 and 55 were stillbirths, and 360 and 76 died before 28 days of life, respectively. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of Jordanian and Syrian women are shown and compared in Table 1.

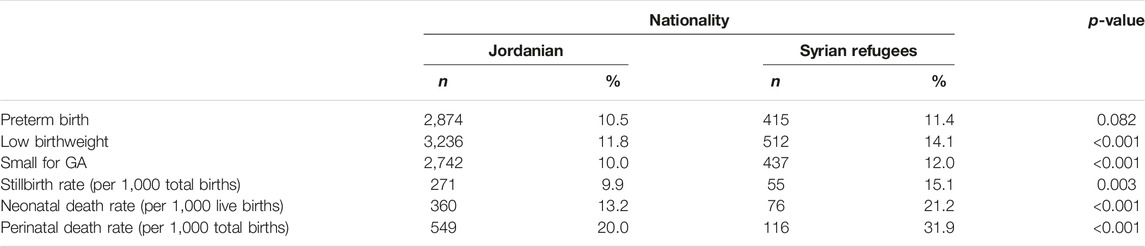

TABLE 1. The sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of Jordanian and Syrian women (Jordan, May 2019 and December 2020).

Syrian women were statistically significantly younger than Jordanian women (12% and 4% under age 20 years, respectively, p < 0.001). The mean (SD) age was 29.3 (6.0) year for Jordanian mothers and 27.3 (6.7) year for Syrian women. Only 11.0% and 1.6% of Jordanian and Syrian women were employed, respectively (p < 0.001). Jordanian women had a higher level of education than Syrian women (31.4% and 5.3% of Jordan and Syrian women had bachelor’s or higher degrees, respectively). Moreover, monthly income was statistically significantly higher for Jordanian women than for Syrian women. Jordanian and Syrian women differed statistically significantly in terms of multiplicity rate, parity, and mode of delivery. The mean (SD) parity was 2.8 (1.7) for Jordanian mothers and 3.3 (2.0) year for Syrian women.

Birth Outcomes

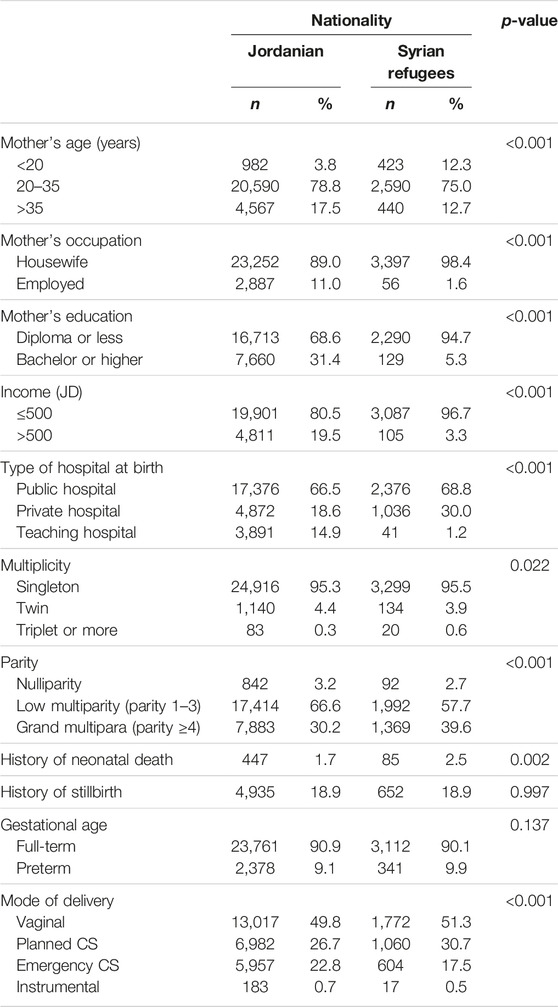

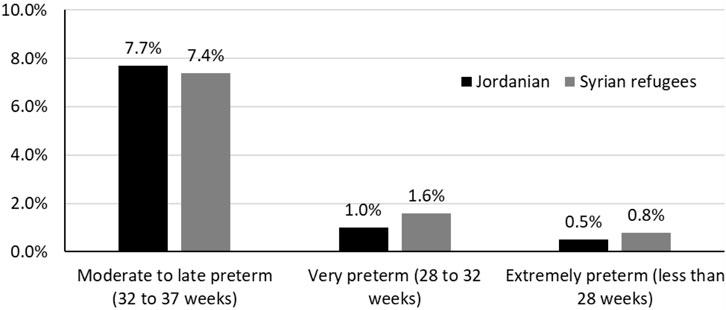

Table 2 shows the birth outcomes for Jordanian and Syrian newborns. In comparison to the babies born to Jordanian women, the proportion of babies born with low weight was statistically significantly higher for Syrian women (11.8% vs. 14.1%, p < 0.001). About 10.0% and 12.0% of babies born to Jordanian and Syrian women were SGA (p < 0.001), respectively.

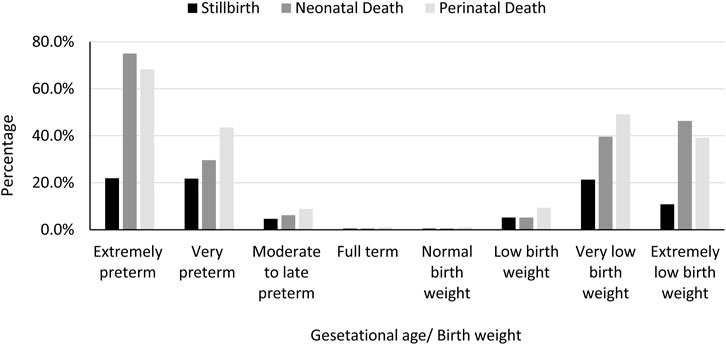

The distribution of preterm delivery and birthweight for Syrian and Jordanian babies is shown in Figures 1, 2, respectively. The stillbirth rate (15.1 vs. 9.9 per 1,000 total births, p = 0.003), the neonatal death rate (21.2 vs. 13.2 per 1,000 live births, p < 0.001), and perinatal death rate (21.2 vs. 13.2 per 1,000 total births, p < 0.001) were statistically significantly higher among Syrian births compared to Jordanian births. The distribution of stillbirths, neonatal deaths and perinatal deaths for babies born to Syrian women according to gestational age and birth weight are shown in Figure 3. The vast majority of deaths occurred among babies born prematurely or with low birth weight.

FIGURE 1. The distribution of preterm delivery among Jordanian and Syrian women (Jordan, May 2019 and December 2020).

FIGURE 2. The distribution of low-birth-weight babies born to Jordanian and Syrian women (Jordan, May 2019 and December 2020).

FIGURE 3. The distribution of stillbirths, neonatal deaths and perinatal deaths for babies born to Syrian women according to gestational age and birth weight (Jordan, May 2019 and December 2020).

Multivariate Analysis

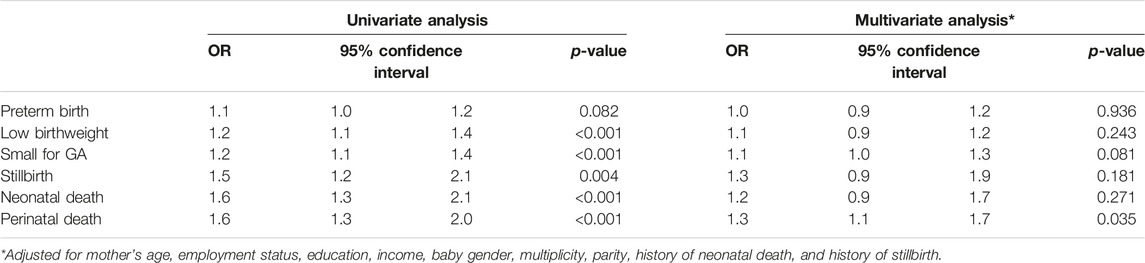

In the bivariate analysis, the proportion of babies born with low birthweight or SGA, stillbirth rate, neonatal death rate, and perinatal death rate was statistically significantly higher among babies born to Syrian women than those born to Jordanian women. After adjusting for sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of women (Table 3), only perinatal death was statistically significantly higher among Syrian babies compared to Jordanian babies (OR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.7, p = 0.035).

TABLE 3. Multivariate analysis of differences in birth outcomes for Jordanian newborns versus Syrian newborns (Jordan, May 2019 and December 2020).

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically assess and compare wide-ranging birth outcomes and disparities among Syrian women in the host community of Jordan. Using comprehensive multicentre data, our analysis specifically provided information about the discrepancies in LBW (<2,500 g), SGA, preterm delivery, birthweight, stillbirth, and perinatal death rate among Syrian and Jordanian women’s births.

Our findings indicate remarkable disparities in pregnancy outcomes among the Syrian women refugees in the host communities of Jordan. Compared to the Jordanian women, the adverse pregnancy outcomes were remarkably higher among the Syrian women refugees, a gravely concerning finding that resonated with a previous retrospective study conducted at two governmental hospitals in northern Jordan [24]. The previous study documented a significant inequality in terms of the rate of caesarean section, anaemia, and lower neonates’ APGAR scores and birthweight among Syrian women deliveries compared to those from Jordan [24]. When summed together, these findings indicate a priority for more effective and tailored maternal-newborns healthcare services directed toward the refugee mothers in Jordan. Transformation is required in the current healthcare policies and interventions implemented in Jordan to improve women refugee’s access to and quality of antenatal, birth, and postnatal healthcare services.

Neonatal health outcomes, in general, have improved considerably in Jordan, as indicated by a slow but progressive decline in neonatal death rates over the past 20 years [25]. According to international reports, Jordan’s overall neonatal mortality rate is recorded at 9 per 1,000 LB [25], and above 14 per 1,000 LB, according to research-based information conducted nationally [19, 26]. Comparing our findings to these national reports, the neonatal and perinatal death rates recorded among Syrian births are remarkably higher than those reported nationally and internationally [19, 25, 26]. Adverse pregnancy outcomes are significantly high among Syrian women refugees on all measured parameters in this study. Our analysis showed that the overall birth outcomes among the Syrian women refugees in Jordan are poor and create a threat to achieving Jordan’s national and international development sustainability goals [27, 28].

Our findings regarding certain birth outcomes (e.g., weight at birth, SGA, low birthweight) were in agreement with those that have been reported among displaced Syrian women in a few comparable studies from Lebanon [6, 29] and Turkey [2, 5, 30]. However, in opposition to our findings, numerous studies from Turkey demonstrated no disparities affecting Syrian women concerning caesarean birth rates [2, 30–33], preterm delivery [30, 32, 33], stillbirth [5, 34], abortion [32, 33], LBW (<2,500 g) [33, 35], and small for gestational birthweight [5]. These discrepancies could suggest that health policies and interventions that facilitate women refugees’ access to and the provision of quality maternal and neonatal services could positively reduce the prevalence and disparities of adverse pregnancy outcomes among women refugees. An international conclusion should be drawn with caution and should be interpreted within its terrestrial context, considering the variations in the quality of healthcare services across countries.

Our findings also showed that other disparities also existed in the sociodemographic characteristics that are related to birth outcomes of the mothers from Syria compared to those from Jordan, specifically in terms of younger age, income, unemployment, and educational attainment. The results showed that the difference can be attributed to the background variables among the Jordanian and Syrian women. After controlling for these factors, the difference between the two groups of women seems to become not significant. These sociodemographic discrepancies could have contributed to worsening pregnancy outcomes and widening the healthcare disparity gap among the Syrian women refugees in Jordan. Low socioeconomic state [6], early-age/adolescent pregnancy [35], infrequent antenatal visits [6, 32, 34, 35], and the late arrival to skilled maternal care at birth [5, 24, 35] are contributing factors to adverse pregnancy outcomes that were prevailing among women refugees from Syria in other countries. The adverse birth outcomes are multifactorial, and this should be considered when designing and delivering care services to women refugees in the host countries.

Adolescent pregnancy, in particular, has been consistently observed to be prevalent among Syrian displaced women compared to native women in host countries [2, 35–38], which is in accordance with our comparison in Jordan. Adolescent pregnancy is one crucial factor associated with adverse birth outcomes worldwide [39, 40], which is similar to the case of Jordan [41]. The socioeconomic and healthcare needs, risks and pregnancy outcomes of Syrian adolescents and young women should receive further attention through humanitarian field assessments and research work. Our findings sheds light on the importance of designing healthcare policies and services to provide additional support for the vulnerable groups of women refugees.

Strengths and Limitations

Retrospective studies on expositing data are efficient means of gathering data in public health studies; however, researchers are limited with the nature and amount of the data excited. Although the current analysis was conducted in five leading referral hospitals in Jordan, the findings might only be transferred to some Jordanian women and Syrian refugees that might receive care outside these hospitals in the country. Despite this limitation, this study is the first multicentre study in Jordan to compare wide-ranging sociodemographic and birth outcomes between displaced Syrian refugees and Jordanian women. This study pave the way for future improvement in obstetric, neonatal, and birth outcomes and there related surveillance system.

Conclusion

Syrian refugee mothers had higher rates of adverse birth outcomes and inequalities than women in Jordan’s host communities. Ongoing evaluation of pregnancy outcomes is essential to enhance our understanding of the healthcare disparities among refugees in the host communities. However, it is more important to foster a comprehensive understanding of the multilevel contributing factors to help develop strategies on micro and macro levels for controlling these factors. Our findings suggest a healthcare priority for better improvement in the policies and provision of maternal-neonatal care services to women refugees in Jordan. Healthcare policies and services may be designed to provide additional support for these vulnerable groups of women refugees.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Jordan University of Science and Technology. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Giovetti, O. Forced Migration: 6 Causes and Examples2019 (2021). Available From: https://www.concernusa.org/story/forced-migration-causes/ (Accessed August 12, 2021).

2. Çelik, İH, Arslan, Z, Ulubaş Işık, D, Tapısız, ÖL, Mollamahmutoğlu, L, Baş, AY, et al. Neonatal Outcomes in Syrian and Other Refugees Treated in a Tertiary Hospital in Turkey. Turkish J Med Sci (2019) 49(3):815–20. doi:10.3906/sag-1806-86

3. Harakow, HI, Hvidman, L, Wejse, C, and Eiset, AH. Pregnancy Complications Among Refugee Women: A Systematic Review. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scand (2021) 100(4):649–57. doi:10.1111/aogs.14070

4. Gibson-Helm, ME, Teede, HJ, Cheng, IH, Block, AA, Knight, M, East, CE, et al. Maternal Health and Pregnancy Outcomes Comparing Migrant Women Born in Humanitarian and Nonhumanitarian Source Countries: A Retrospective, Observational Study. Birth (2015) 42(2):116–24. doi:10.1111/birt.12159

5. Ozel, S, Yaman, S, Kansu-Celik, H, Hancerliogullari, N, Balci, N, and Engin-Ustun, Y. Obstetric Outcomes Among Syrian Refugees: A Comparative Study at a Tertiary Care Maternity Hospital in Turkey. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet (2018) 40(11):673–9. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1673427

6. Elshal, H, Chour, M, Halim, SA, Kharpoutli, S, and Raad, H. Factors Affecting Pregnancy Outcome in Refugee Mothers in Lebanon. BAU J - Health Well-Being (2021) 3(2):1–7. doi:10.54729/2789-8288.1128

7. World Vision. Syrian Refugee Crisis: Facts, FAQs, and How to Help WA. USA: World Vision, Inc (2021).

8. Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan. Regional Strategic Overview 2021-2022: RSO (2021). Available From: http://www.3rpsyriacrisis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/RSO2021.pdf (Accessed July 24, 2021).

9. Operational Data Portal. Refugee Situation. Syria Regional Refugee Response -Jordan: Operational Data Portal 2021 (2021). Available From: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/36 (Accessed July 24, 2021).

10. Brown, H, Giordano, N, Maughan, C, and Wadeson, A. The 2019 Vulnerability Assessment Framework (VAF). The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Action Against Hunger UK’s Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Services. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organisation (2019).

11. Grameen Crédit Agricole Foundation (GCAF), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (GCAF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Assessing the Needs of Refugees for Financial and Non-Financial Services—Jordan (2018). Available From: https://www.unhcr.org/fr-fr/en/media/assessing-needs-refugees-financial-and-non-financial-services-jordan (Accessed July 24, 2021).

12. UNHCR. Health-Refugees From All Nationalities: UNHCR; 2021 (2021). Available From: https://help.unhcr.org/jordan/en/helpful-services-unhcr/health-services-unhcr/ (Accessed July 24, 2021).

13. Al-Rousan, T, Schwabkey, Z, Jirmanus, L, and Nelson, BD. Health Needs and Priorities of Syrian Refugees in Camps and Urban Settings in Jordan: Perspectives of Refugees and Health Care Providers. East Mediterr Health J (2018) 24(3):243–53. doi:10.26719/2018.24.3.243

14. Amiri, M, El-Mowafi, IM, Chahien, T, Yousef, H, and Kobeissi, LH. An Overview of the Sexual and Reproductive Health Status and Service Delivery Among Syrian Refugees in Jordan, Nine Years Since the Crisis: A Systematic Literature Review. Reprod Health (2020) 17(1):166–20. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-01005-7

15. Clark, CJ, Spencer, RA, Khalaf, IA, Gilbert, L, El-Bassel, N, Silverman, JG, et al. The Influence of Family Violence and Child Marriage on Unmet Need for Family Planning in Jordan. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care (2017) 43(2):105–12. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101122

16. Khader, YS, Alyahya, M, El-Khatib, Z, Batieha, A, Al-Sheyab, N, and Shattnawi, K. The Jordan Stillbirth and Neonatal Mortality Surveillance (JSANDS) System: Evaluation Study. J Med Internet Res (2021) 23(7):e29143. doi:10.2196/29143

17. Khader, YS, Shattnawi, KK, Al-Sheyab, N, Alyahya, M, and Batieha, A. The Usability of Jordan Stillbirths and Neonatal Deaths Surveillance (JSANDS) System: Results of Focus Group Discussions. Arch Public Health (2021) 79(1):29–10. doi:10.1186/s13690-021-00551-1

18. Khader, YS, Alyahya, M, Batieha, A, and Taweel, A. JSANDS: A Stillbirth and Neonatal Deaths Surveillance System. In: 2019 IEEE/ACS 16th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA); Nov. 3 2019 to Nov. 7 2019; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (2019).

19. Al-Sheyab, NA, Khader, YS, Shattnawi, KK, Alyahya, MS, and Batieha, A. Rate, Risk Factors, and Causes of Neonatal Deaths in Jordan: Analysis of Data From Jordan Stillbirth and Neonatal Surveillance System (JSANDS). Front Public Health (2020) 8:595379. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.595379

20. Shattnawi, KK, Khader, YS, Alyahya, MS, Al-Sheyab, N, and Batieha, A. Rate, Determinants, and Causes of Stillbirth in Jordan: Findings From the Jordan Stillbirth and Neonatal Deaths Surveillance (JSANDS) System. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2020) 20(1):571–8. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03267-2

21. World Health Organization. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems ICD-10: Tenth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2004).

22. Howson, CP, Kinney, MV, McDougall, L, and Lawn, JE. Born Too Soon: Preterm Birth Matters. Reprod Health (2013) 10(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S1

23. World Health Organization. The WHO Application of ICD-10 to Deaths During the Perinatal Period: ICD-PM. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2016).

24. Alnuaimi, K, Kassab, M, Ali, R, Mohammad, K, and Shattnawi, K. Pregnancy Outcomes Among Syrian Refugee and Jordanian Women: A Comparative Study. Int Nurs Rev (2017) 64(4):584–92. doi:10.1111/inr.12382

25. UNICEF. Country Profiles: Jordan 2021 (2021). Available From: https://data.unicef.org/country/jor/ (Accessed March 27, 2022).

26. Batieha, AM, Khader, YS, Berdzuli, N, Chua-Oon, C, Badran, EF, Al-sheyab, NA, et al. Level, Causes and Risk Factors of Neonatal Mortality, in Jordan: Results of a National Prospective Study. Matern Child Health J (2016) 20(5):1061–71. doi:10.1007/s10995-015-1892-x

27. World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030): early childhood development (2018). Available From: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/276423/A71_19Rev1-en.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed July 24, 2021).

28. United Nations. United Nations Jordan; 2022 (2022). Available From: https://jordan.un.org/en/sdgs/3 (Accessed July 24, 2021).

29. Abdulrahim, S, El Rafei, R, Beydoun, Z, El Hayek, GY, Nakad, P, and Yunis, K. A Test of the Epidemiological Paradox in a Context of Forced Migration: Low Birthweight Among Syrian Newborns in Lebanon. Int J Epidemiol (2019) 48(1):1024–86. doi:10.1093/ije/dyz087

30. Vural, T, Gölbaşı, C, Bayraktar, B, Gölbaşı, H, and Yıldırım, AG. Are Syrian Refugees at High Risk for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes? A Comparison Study in a Tertiary Center in Turkey. J Obstet Gynaecol Res (2021) 47(4):1353–61. doi:10.1111/jog.14673

31. Güngör, ES, Seval, O, İlhan, G, and Verit, FF. Do Syrian Refugees Have Increased Risk for Worser Pregnancy Outcomes? Results of a Tertiary Center in İstanbul. Suriyeli Mültecilerin Daha Kötü Gebelik Sonuçları Açısından Artmış Riskleri Var Mıdır? İstanbul'da Tersiyer bir Merkezin Sonuçları (2018) 15(1):23–7. doi:10.4274/tjod.64022

32. Kiyak, H, Gezer, S, Ozdemir, C, Gunkaya, S, Karacan, T, and Gedikbasi, A. Comparison of Delivery Characteristics and Early Obstetric Outcomes Between Turkish Women and Syrian Refugee Pregnancies. Niger J Clin Pract (2020) 23(1):12–7. doi:10.4103/njcp.njcp_10_18

33. Sayili, U, Ozgur, C, Bulut Gazanfer, O, and Solmaz, A. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics and Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes Between Turkish Citizens and Syrian Refugees With High-Risk Pregnancies. J Immigrant Minor Health (2021) 24:1177–85. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01288-3

34. Kanmaz, AG, İnan, AH, Beyan, E, Özgür, S, and Budak, A. Obstetric Outcomes of Syrian Refugees and Turkish Citizens. Arch Iranian Med (2019) 22(9):482–8.

35. Erenel, H, Aydogan Mathyk, B, Sal, V, Ayhan, I, Karatas, S, and Koc Bebek, A. Clinical Characteristics and Pregnancy Outcomes of Syrian Refugees: A Case-Control Study in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2017) 295(1):45–50. doi:10.1007/s00404-016-4188-5

36. Bacanakgl, BH, Kaban, I, Yildirim, SG, and Sinaci, E. Birth Characteristics of Syrian Refugees at a Tertiary Medical Center in Istanbul, Turkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2019) 234:e140–e. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.08.466

37. Dopfer, C, Vakilzadeh, A, Happle, C, Kleinert, E, Müller, F, Ernst, D, et al. Pregnancy Related Health Care Needs in Refugees—A Current Three Center Experience in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(9):1934. doi:10.3390/ijerph15091934

38. Turkay, Ü, Aydın, Ü, Çalışkan, E, Salıcı, M, Terzi, H, and Astepe, B. Comparison of the Pregnancy Results Between Adolescent Syrian Refugees and Local Adolescent Turkish Citizens Who Gave Birth in Our Clinic. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med (2020) 33(8):1353–8. doi:10.1080/14767058.2018.1519016

39. Wong, SP, Twynstra, J, Gilliland, JA, Cook, JL, and Seabrook, JA. Risk Factors and Birth Outcomes Associated With Teenage Pregnancy: A Canadian Sample. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol (2020) 33(2):153–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2019.10.006

40. Karataşlı, V, Kanmaz, AG, İnan, AH, Budak, A, and Beyan, E. Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes of Adolescent Pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod (2019) 48(5):347–50. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.02.011

Keywords: Jordan, mortality, Syrian refugee, pregnancy outcomes, neonates

Citation: Al-Shatanawi TN, Khader Y, Abdel Razeq N, Khader AM, Alfaqih M, Alkouri O and Alyahya M (2023) Disparities in Obstetric, Neonatal, and Birth Outcomes Among Syrian Women Refugees and Jordanian Women. Int J Public Health 68:1605645. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605645

Received: 01 December 2022; Accepted: 19 October 2023;

Published: 03 November 2023.

Edited by:

Andrea Madarasova Geckova, University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, SlovakiaReviewed by:

Ankit Anand, Institute for Social and Economic Change, IndiaOne reviewer who chose to remain anonymous

Copyright © 2023 Al-Shatanawi, Khader, Abdel Razeq, Khader, Alfaqih, Alkouri and Alyahya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nadin Abdel Razeq, bi5hYmRlbHJhemVxQGp1LmVkdS5qbw==

Tariq N. Al-Shatanawi1

Tariq N. Al-Shatanawi1 Yousef Khader

Yousef Khader Nadin Abdel Razeq

Nadin Abdel Razeq