- 1Department of Psychology, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, China

- 2Shanghai Pudong New Area Mental Health Center, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Objectives: Family atmosphere is a significant predictor of internet addiction in adolescents. Based on the vulnerability model of emotion and the compensatory internet use theory, this study examined whether self-esteem and negative emotions (anxiety, depression) mediated the relationship between family atmosphere and internet addiction in parallel and sequence.

Methods: A total of 3,065 Chinese middle school and high school students (1,524 females, mean age = 13.63 years, SD = 4.24) participated. They provided self-reported data on demographic variables, family atmosphere, self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and internet addiction through the Scale of Systemic Family Dynamic, Self-Esteem Scale, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, Self-Rating Depression Scale, and Internet Addiction Test, respectively. We employed Hayes PROCESS macro for the SPSS program to scrutinize the suggested mediation model.

Results: It revealed that self-esteem, anxiety, and depression mediated the relationship between family atmosphere and internet addiction in parallel and sequence. The pathway of family atmosphere-self-esteem-internet addiction played a more important role than others.

Conclusion: The present study confirmed the mediating role of self-esteem and negative emotions between family atmosphere and internet addiction, providing intervention studies with important targeting factors.

Introduction

Science and technology have made the internet more accessible to the general public. In particular, the virtual world has become an indispensable part of life for teenagers born during the internet age. According to China Minors’ Internet use Report 2020 [1], the internet penetration rate of minors in China reached 99.2%. Furthermore, the age of their first exposure to the internet declined over the year, with 78% having internet use experience before 10 years old. While the internet has brought some advantages to adolescents, such as attending online courses, the negative effects of excessive internet use should not be overlooked. Additionally, excessive internet use can lead to Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) [2]. Internet addiction (IA) was coined by American psychiatrist Goldberg in 1994. It was characterized by continuous desires to surf the internet, out-of-control over internet use, withdrawal symptoms after removal, etc.

Scholars have made continuous attempts to investigate the social and physiological factors associated with IAD, and there is supporting evidence suggesting that family environment, negative emotions, and self-esteem play a significant role. Family atmosphere, or family environment, has long been recognized as an essential predictor of problematic internet use [3]. However, the pathways through which they are associated with each other remain unclear. In the meantime, negative emotions such as anxiety and depression have always been considered a result of improper family atmospheres [4] and a related issue to internet addiction among adolescents [5, 6]. Similarly, self-esteem is another potential mediator between family atmosphere and internet addiction among adolescents, as indicated by preceding literature [7, 8]. In brief, the present study explored the intermediate mechanisms that may rationalize the association between family atmosphere and internet use in adolescents by considering the role of negative emotions and self-esteem. The results may enlighten relevant intervention work.

Family Atmosphere and Internet Addiction

The term “family atmosphere” pertains to the conditions and surroundings in which a child grows up. As a dimension of family characteristics, it was usually assessed by the Family Dynamic Scale and the Scale of Systemic Family Dynamic (SSFD) [9]. A study proposed that family atmosphere consists of three specific relational dimensions: the mother-child relationship, the parental relationship, and the parents’ restriction on children’s behavior [10].

Previous studies have indicated that the presence of an unsatisfactory family atmosphere, characterized by low levels of family satisfaction and cohesion and a high level of conflict between parents and children, is significantly associated with the development of internet addiction amongst adolescents [3, 11]. Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that good family atmosphere can predict a substantial reduction of IAD in adolescents 2 years later [12], verifying their causal relationship. According to the compensatory internet use theory (CIUT [13]), adolescents who experience unsatisfactory family environments may turn to the internet as a means of escaping their reality and fulfilling unmet emotional needs, leading to the emergence of internet addiction [14]. This assumption has been confirmed by some preliminary studies conducted among Chinese middle school students [15]. Albeit these initial findings, the intermediate mechanisms that may account for the association of family atmosphere and internet use have not been examined empirically, amongst which are self-esteem and negative emotions (i.e., depression, anxiety).

Self-Esteem as a Potential Mediator

Self-esteem is the positive or negative attitude towards oneself through social comparisons [16]. Accordingly, the main component of self-esteem is worthiness, such that high self-esteem implies that one thinks s/he is good enough [17]. The positive relationship between family atmosphere and self-esteem has been well-established among teenagers from different cultures [7, 18]. Meanwhile, self-esteem and problematic internet use were negatively associated, supported by both cross-sectional [19–25] and longitudinal study findings [26].

Researchers in the past have only indirectly verified the mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between family atmosphere and internet addiction due to the use of various measures to assess family atmosphere. For instance, Yao et al. [22] found that self-esteem mediated parents’ warmth and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Similar findings were confirmed when family function was served as the independent variable [15]. The underlying mechanism may be that good family atmosphere promotes high self-esteem in adolescents, reducing their intention of seeking compensation on the internet and consequently decreasing the risks of internet addiction. According to Griffiths [27] and Niemz et al. [19], individuals with low self-esteem may derive great satisfaction from using the internet and treat it as a coping strategy to compensate for deficiencies, such as low self-esteem [19, 27].

Anxiety and Depression as Potential Mediators

Negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, typically refer to extreme emotional reactions and persistent maladaptive emotions that negatively evaluate one’s situation [28, 29]. Though anxiety and depression often co-occur, they are independent of each other and represent distinguishable categories of negative emotions [30].

Adolescents with unhealthy family atmosphere are likely to experience anxiety and depression. For instance, Berryhill and Smith [31] found a positive relationship between chaotically disengaged family functioning and anxiety symptoms. Similarly, poor systematic family dynamics, lack of intimacy and disharmony were predictors of depression and suicidal ideas in adolescents [32–36].

Adolescents’ negative emotions were proven to predict internet addiction over time. For example, high anxiety [37] and depression [38] were risk factors of problematic internet use [39]. According to the compensatory internet use theory, adolescents may use the internet to alleviate these negative emotions [13].

To sum up, adolescents may attempt to alleviate anxiety and depression caused by negative family environments by turning to the internet, a topic that necessitates empirical examination.

Chain Mediation of Self-Esteem and Negative Emotions

The two sources of mediators proposed above are also closely associated with each other [40]. Specifically, individuals with low self-esteem were more susceptible to negative emotions, potentially because being in a state of low self-esteem for a long time weakened their ability to regulate emotions [41–43]. This is in line with the vulnerability model of emotion, suggesting low self-esteem increases the likelihood of experiencing depression and anxiety (see meta-analysis [44]).

Though the two negative emotions of concern often co-occur in adolescents [45], anxiety was found more robustly predicted depression than the other way around [46, 47]. The potential reason is that anxiety creates a sense of helplessness [48], which in turn precipitates depressive signs of despair and perceived loss [49]. In sum, family atmosphere may be associated with internet addiction via four chain mediation pathways: self-esteem—anxiety, self-esteem—depression, self-esteem—anxiety—depression, and anxiety—depression.

The Present Study

In sum, there is a lack of literature investigating the mediating role of self-esteem and negative emotions between family atmosphere and problematic internet use. The present study aims to fill this research gap by conducting a relatively large-scale survey among Chinese adolescents. Furthermore, in line with previous studies, factors that may confound the examination of the proposed model were controlled, including age, gender, and self-rated family financial status [24, 50]. We hypothesized that: 1) good family atmosphere is negatively associated with internet addiction; 2) self-esteem and negative emotions partially mediate (1) in parallel and sequence.

Methods

Participant

We employed a multi-stage stratified sampling technique to obtain our data. Initially, we randomly chose two districts out of the 16 districts situated in Shanghai. Subsequently, we randomly selected three middle and three high schools from each district. Finally, we randomly picked two classes from every grade level of each school. Participants filled out the paper-pencil test under the guidance of their psychological teachers in school, and 3,358 complete copies were received (response rate of 81.7%). The answers of 293 students were discarded due to high missing data rates, resulting in 3,065 participants (1,527 girls, 13.63 ± 4.24 years) included in the data analyses. Approval from the school principals was obtained before the survey, and written consent was obtained from all participants and their parents.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Form

Sociodemographic information was collected, including age, gender, grade, and self-rated family financial satisfaction (0: not at all satisfied to 10: completely satisfied).

Family Atmosphere

Family atmosphere was measured by the Self-rating Scale of Systemic Family Dynamic (SSFD [51]), which contains 23 items and four dimensions (i.e., family atmosphere, individualization, system logic, and illness concept). Adolescents rated items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). The eight items that belong to family atmosphere dimension were included in the analysis. A higher score indicates a better family atmosphere. The validated Chinese version was used [52], and Cronbach’s alpha of the family atmosphere dimension was 0.87 in the present study.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was measured by the Self-Esteem Scale (SES) developed by Rosenberg [17]. It consists of 10 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). After reversely scoring items 3, 5, 9, and 10 and adding them up with the rest, a higher SES total score indicates high self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of SES was good (0.89) in the present study.

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured by the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) developed by Zung ([53]). It consists of 20 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no or little time) to 4 (most or all of the time). A total SAS score was calculated by first reversely scoring items of 5, 9, 13, 17, and 19, then adding up each item and multiplying it by 1.25. A score below 50, between 50 and 59, between 60 and 69, and above 70 indicates free from anxiety, mild anxiety, moderate anxiety, and severe anxiety, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of SAS was good (0.82) in the present study.

Depression

Depression was measured by the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) developed by Zung [54]. It consists of 20 items, rated on a 4-point scale from 1 (no or little time) to 4 (most or all of the time). A total SDS score was calculated by first reversely scoring items of 2, 5, 6, 11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 18, and 20, then adding up each item and multiplying it by 1.25. A score below 53, between 53 and 62, between 63 and 72, and above 73 indicates free from depression, mild depression, moderate depression, and severe depression, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of SDS was good (0.84) in the present study.

Internet Addiction

Internet addiction was measured by the Internet Addiction Test (IAT-20) developed by Young [55]. The questionnaire comprises 20 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (always true), with higher total scores representing higher degrees of internet addiction. The validated Chinese version was used in the present study, which has good reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents [56]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of IAT was excellent (0.90) in the present study.

Analytic Plan

We examined the missing data rate for all variables and used mean score imputation for variables with less than 10% missing data [57]. Two demographic variables, namely, parent’s education level and the number of siblings, were excluded from the analyses because they contained over 10% missing data. Afterward, descriptive statistics and correlations between variables were calculated. Lastly, Hayes’ PROCESS macro, version 4.0, model 6 (a linear model) [58] was used to test the chain mediation model through which family atmosphere was hypothesized to influence internet use. Mediators examined included self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. In addition, demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, and self-rated family financial satisfaction) that may confound the mediation model were controlled by adding them as covariates. Bootstrapping procedures with 5,000 replications were used to calculate confidence intervals for estimates of the indirect effects, with the confidence interval did not include zero indicating a significant indirect effect. Pairwise contrasts compared the relative strength of the indirect pathways involved in a mediation model. Furthermore, the effect sizes of the mediation effects were represented by the proportion of the total effect explained by the indirect effect [59].

Result

Participant Characteristics

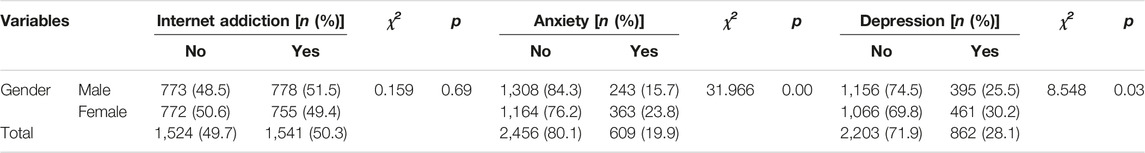

In the present study, the average score of family atmosphere, self-esteem, anxiety, depression, internet addiction, and self-rated family financial satisfaction was 65.46 (SD = 22.59), 30.84 (SD = 6.11), 41.83 (SD = 33.59), 46.49 (SD = 29.88), 41.75 (SD = 11.31), and 7.82 (SD = 1.98), respectively. As was shown in Table 1, 50.3%, 19.9%, and 28.1% of the participants had experienced internet addiction, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, respectively. Furthermore, the detection rate of anxiety and depression was higher in females than in males (anxiety: χ2 = 31.97, depression: χ2 = 8.55), thus gender was controlled in the mediation analysis.

TABLE 1. The detection rate and gender difference of internet addiction, anxiety, and depression in adolescents (China, 2022).

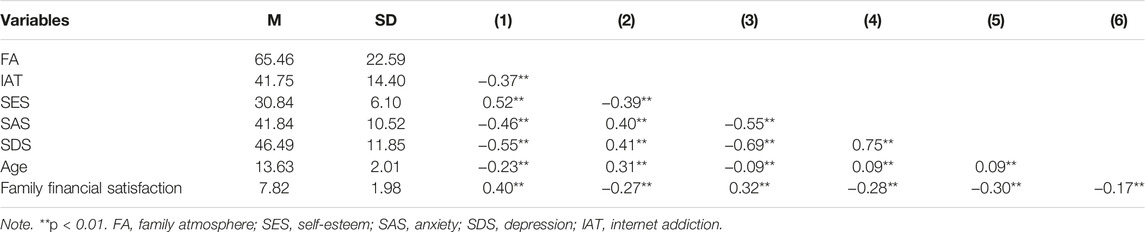

Correlation Analyses Between Main Variables

As expected, family atmosphere was positively associated with self-esteem (r = 0.522, p < 0.01) and negatively associated with internet addiction (r = −0.37, p < 0.01), anxiety (r = −0.457, p < 0.01) and depression (r = −0.551, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Internet addiction was negatively associated with self-esteem (r = −0.393, p < 0.01) and positively associated with anxiety (r = 0.402, p < 0.01) and depression (r = 0.405, p < 0.01). In addition, age and family financial satisfaction was significantly associated with all the examined variables (Table 2), and thus were controlled in the mediation model.

TABLE 2. Correlations between family atmosphere, internet addiction, self-esteem, anxiety, depression, age, and family financial satisfaction (n = 3,065) (China, 2022).

Chain Mediation Model

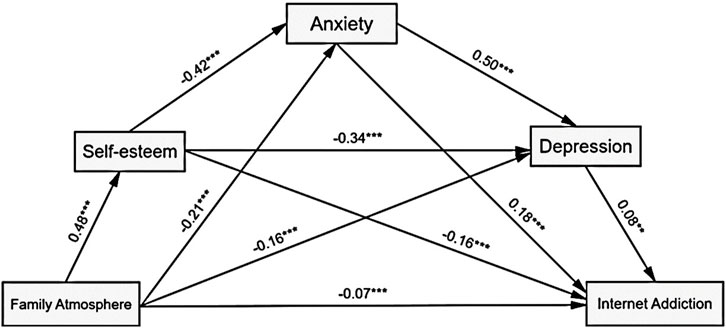

The overall model accounted for 53.5% of the variance in the internet addiction total score (R2 = 0.29, F (7, 3,029) = 173.28, p < 0.001). As presented in Figure 1, family atmosphere had a significant positive predictive effect on self-esteem (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), and it negatively predicted anxiety (β = −0.21, p < 0.001), depression (β = −0.16, p < 0.001), and internet addiction (β = −0.07, p < 0.001). Furthermore, self-esteem negatively predicted anxiety (β = −0.42, p < 0.001), depression (β = −0.34, p < 0.001), and internet addiction (β = −0.16, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, anxiety had a positive relationship with depression (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and internet addiction (β = 0.18, p < 0.001), and depression also positively predicted internet addiction (β = 0.08, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 1. The chain mediation model of the association between family atmosphere and internet addiction with self-esteem, anxiety, and depression as mediators. The path estimation shown with each arrow is the standardized coefficient after adjusting for age, gender and self-rated family financial satisfaction. ***p < 0.001, **0.001 < p < 0.01 (China, 2022).

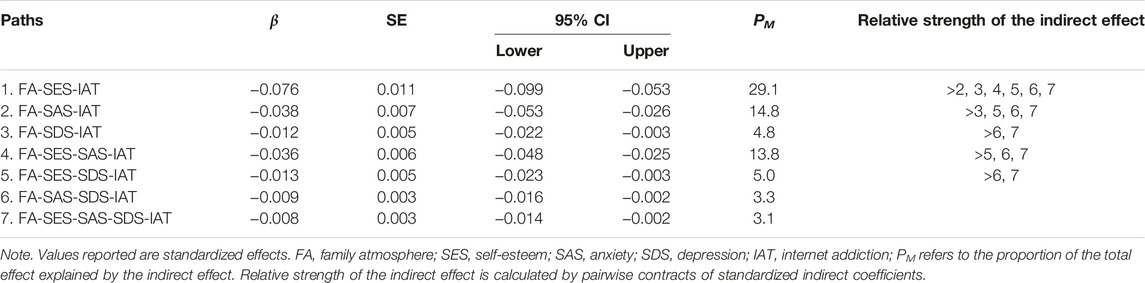

The direct effect of family atmosphere on internet addiction was significant (β = −0.0580, SE = 0.0124, 95% CI = [−0.0824, −0.0336]), as were the seven indirect pathways (Figure 1; Table 3). Roughly 73.9% of the variance in internet addiction accounted for by family atmosphere was explained by self-esteem (PM = 29.1%), anxiety (PM = 14.8%), depression (PM = 4.8%), self-esteem-anxiety (PM = 13.8%), self-esteem-depression (PM = 5.0%), anxiety-depression (PM = 3.3%), and self-esteem-anxiety-depression (PM = 3.1%). In particular, the indirect effect of “family atmosphere—self-esteem—internet addiction” was considerably more significant than the other six indirect pathways (Table 3). Two important secondary pathways were family atmosphere-anxiety-internet addiction, and family atmosphere-self-esteem-anxiety-internet addiction.

TABLE 3. The model for the mediating effect of self-esteem, anxiety, and depression on the association of family atmosphere and internet use (n = 3,065) (China, 2022).

Discussion

The present study examined the mediating chain of self-esteem—anxiety—depression in the relationship between family atmosphere and internet addiction within a large sample of Chinese adolescents. We found that family atmosphere was positively associated with self-esteem, and negatively associated with internet addiction, anxiety and depression. Secondly, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression mediated the relationship between family atmosphere and internet use in parallel and sequence, which was in line with our hypotheses. Next, we start with explanations and implications of the main findings, followed by limitations and suggestions for future studies.

Family Atmosphere and Internet Addiction

Consistent with previous studies, we found that inferior family atmosphere increased the risk of adolescents’ internet addiction [60, 61]. As one of the earliest and most intimate growing environments [62], family atmosphere profoundly affects adolescents’ mental health [63]. According to the compensatory internet use theory [13], adolescents exposed to long-term familial stress and conflict are likely to use the internet to meet their unmet needs (e.g., satisfaction and pleasure [64, 65]). In contrast, warm and harmonious family atmosphere provides adolescents with a sense of security and belonging, which help meet their psychological needs and protect them from internet addiction [66].

The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem

As one of the examined mediators, self-esteem was found partially mediated the relationship between family atmosphere and internet addiction. Moreover, we found that the pathway solely mediated by self-esteem had a greater influence than the other six pathways. Consequently, it can be inferred that an adverse family environment primarily diminishes one’s self-esteem rather than eliciting negative emotions to trigger internet addiction. Thus, implementing interventions that focus on enhancing self-esteem is likely to yield more positive results. The sociometric theory of self-esteem suggests that long-term exposure to an environment full of rejection, social exclusion and indifference reduces one’s self-esteem [67, 68]. Meanwhile, the cognitive-behavioral model of internet addiction proposed that low self-esteem constitutes a risk factor for internet addiction [69], which was validated by empirical findings in adolescents [8, 25]. The underlying mechanism of this mediation relationship may be that adolescents with low self-esteem due to inferior family atmosphere find it difficult to realize their values in real life but the virtual world, which may exacerbate their internet use and further increase the risk of internet addiction over time [70].

The Mediating Role of Negative Emotions

The two examined negative emotions (i.e., anxiety and depression) mediated the association between family atmosphere and internet addiction in parallel and sequence. Previous studies showed that family atmospheres such as tension, lack of intimacy, and indifference led to anxiety and depression in adolescents [71, 72]. As a result, adolescents turned to internet use to escape reality and gain pleasure. This matched well with the self-medication model [73] and the compensatory theory of internet use [74], which assumes that internet use is an outlet for negative emotions caused by interior family atmospheres. Furthermore, the chain emotion-mediated pathway from anxiety to depression is consistent with previous models and findings [74, 75], implying anxiety may cause depression and later-on internet addiction. In addition, the relative strength of pathways with anxiety involved was larger than that of depression, emphasizing a more central role of anxiety than depression in the proposed mediation model.

The Chain Mediation

It was also found that self-esteem, anxiety, and depression mediated the association between family atmosphere and internet addiction in sequence. Notably, the pathway of “family atmosphere—self-esteem—anxiety—internet addiction” was more important than the other three chain pathways. This is in line with the vulnerability model of emotion, indicating low self-esteem as a risk factor for anxiety [44]. Together with the salient effect of pathways with only self-esteem and anxiety as mediators found in the model, the present findings emphasized the critical roles of self-esteem and anxiety between inferior family atmosphere and internet addiction.

Altogether, the present findings confirmed and expanded the cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use [69] by showing that not only environmental (i.e., family atmosphere) and psychopathological factors (i.e., anxiety, depression), but negative perceptions (i.e., self-esteem) play a key role in making individuals seek success and escape from reality through the internet [76, 77].

Implications

The present study has significant clinical implications. It suggests that addressing family atmosphere, self-esteem, anxiety, and depression may help adolescents reduce the risk of internet addiction. For instance, systemic family therapy (SFT [78, 79]) can improve family atmosphere and give warmth and mutual support, which may help promote adolescents’ self-esteem and further reduce the risk of internet addiction. As to negative emotions, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT [80, 81]) and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT [82, 83]) were found effective in boosting emotions and arming people with effective emotion regulation skills.

Limitations

This pioneering study used a relatively large sample to investigate the mediating role of self-esteem and negative emotions between family atmosphere and internet use in Chinese adolescents. Albeit the implications of our research findings, some limitations should be realized. Firstly, the sampling approach employed in this study guaranteed a representative sample of adolescents in Shanghai. However, it is imperative to recognize that these findings may not be universally applicable to all Chinese teenagers, much less to those worldwide. To improve the generalizability of these findings, future studies should explore more varied samples. Secondly, although the Hayes’s approach was eligible to test the proposed chain mediation model, the model’s goodness of fit cannot be established, necessitating the use of alternative software like AMOS to perform the model. Thirdly, although previous longitudinal studies generally supported that the mediators examined here are consequences rather than causes of inferior family atmosphere [12, 26, 35], their causal relationship with internet use remains relatively unclear. Specifically, anxiety and depression may interact with pathological internet use in a mutually self-enhancing way. Future longitudinal studies can help clarify their relationship beyond correlation. Lastly, Young’s internet addiction test (IAT-20 [55]) assesses internet use severity in general, while leaving the various purposes of use undistinguished. Of note, using the internet for some purposes (e.g., gaming, cyberbullying, sexting) may be more hazardous than others (e.g., searching literature, remote studying), and they are associated with different antecedent factors [84]. Hence, studies in the future can refine the present model by differentiating various internet use purposes.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated a strong negative relationship between adolescents’ family atmosphere and internet addiction, suggesting that an inferior family atmosphere posed a risk factor for internet addiction. More importantly, we found that this relationship was partially mediated by self-esteem and negative emotions (i.e., anxiety and depression) in parallel and sequence. And the pathway of family atmosphere—self-esteem—internet addiction played a more critical role than others. The present study revealed the pathogenesis of internet use from a comprehensive environment-personality-emotion perspective, which provides future intervention studies with important targeting factors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Mental Health Center affiliated with Tongji University in Shanghai (No. PDJWLL2019008). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and data collection, YS and MH; formal analysis, YS, ZT, and ZG; writing—original draft, YS, ZT, and ZG; writing—review and editing, YL; funding acquisition, MH and YL; All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Foundation granted to MH (Grant Number: 201940161). The publication fee was supported by “A survey on the growth and development index of adolescents in Shanghai” granted to YL and “Research on Ideological and political elements of Academic norms and thesis writing” granted to YL by the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ji, WM, Shen, J, Yang, BY, and Ji, L. A Report on the Internet Use of Chinese Minors. China: China Internet Network Information Center (2021).

2. Shaw, M, and Black, DW. Internet Addiction: Definition, Assessment, Epidemiology and Clinical Management. CNS Drugs (2008) 22(5):353–65. doi:10.2165/00023210-200822050-00001

3. Huang, RL, Lu, Z, Liu, JJ, You, YM, Pan, ZQ, Wei, Z, et al. Features and Predictors of Problematic Internet Use in Chinese College Students. Behav Inf Technol (2009) 28(5):485–90. doi:10.1080/01449290701485801

4. Li, J, Wang, X, Meng, H, Zeng, K, Quan, F, and Liu, F. Systemic Family Therapy of Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression with Epilepsy in Adolescents. Psychiatry Investig (2016) 13(3):305–10. doi:10.4306/pi.2016.13.3.305

5. Yu, L, and Zhou, X. Emotional Competence as a Mediator of the Relationship between Internet Addiction and Negative Emotion in Young Adolescents in Hong Kong. Appl Res Qual Life (2021) 16(6):2419–38. doi:10.1007/s11482-021-09912-y

6. Gao, T, Liang, L, Li, M, Su, Y, Mei, S, Zhou, C, et al. Changes in the Comorbidity Patterns of Negative Emotional Symptoms and Internet Addiction over Time Among the First-Year Senior High School Students: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. J Psychiatr Res (2022) 155:137–45. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.08.020

7. Kanie, N, Iwasaki, K, and Makino, K. Effects of Parents Academic Background and Child’s Gender on Educational Resources in the Family: in Relation to Child’s Perception of Family Atmosphere and Self-Esteem. Res Monogr (2006) 105–8.

8. Aydm, B, and San, SV. Internet Addiction Among Adolescents: The Role of Self-Esteem. Proced - Soc Behav Sci. (2011) 15:3500–5. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.325

9. White, MA, Elder, JH, Paavilainen, E, Joronen, K, Helgadóttir, HL, and Seidl, A. Family Dynamics in the United States, Finland and Iceland. Scand J Caring Sci (2010) 24(1):84–93. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00689.x

10. Kerr, DCR, Leve, LD, Harold, GT, Natsuaki, MN, Neiderhiser, JM, Shaw, DS, et al. Influences of Biological and Adoptive Mothers’ Depression and Antisocial Behavior on Adoptees’ Early Behavior Trajectories. J Abnorm Child Psychol (2013) 41(5):723–34. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9711-6

11. Gao Wenbin, CZ. A Study on Psychopathology and Psychotherapy of Internet Addiction. Adv Psychol Sci (2006) 14(04):596.

12. Yu, L, and Shek, DTL. Internet Addiction in Hong Kong Adolescents: A Three-Year Longitudinal Study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol (2013) 26(3):S10–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.03.010

13. Kardefelt-Winther, D. A Conceptual and Methodological Critique of Internet Addiction Research: Towards a Model of Compensatory Internet Use. Comput Hum Behav (2014) 31:351–4. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

14. Lee, VWP, Ling, HWH, Cheung, JCS, Tung, SYC, Leung, CMY, and Wong, YC. Technology and Family Dynamics: The Relationships Among Children’s Use of Mobile Devices, Family Atmosphere and Parenting Approaches. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2022) 39(4):437–44. doi:10.1007/s10560-021-00745-0

15. Shi, X, Wang, J, and Zou, H. Family Functioning and Internet Addiction Among Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Self-Esteem and Loneliness. Comput Hum Behav (2017) 76:201–10. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.028

16. Kirkpatrick, LA, and Ellis, BJ. An Evolutionary-Psychological Approach to Self-Esteem: Multiple Domains and Multiple Functions. In: Brewer MB,, and Hewstone M, editors. Self and Social Identity. Blackwell Publishing (2004). p. 52–77. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-00232-003 (Accessed November 9, 2022).

17. Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Accept Commit Ther Meas Package (1965) 61(52):18.

18. Huamán, DRT, Cordero, RC, and Huamán, ALT. Phubbing, Family Atmosphere and Self-Esteem in Peruvian Teenagers in the Context of Social Isolation. RIMCIS Rev Int Multidiscip En Cienc Soc (2021) 10(3):1–21. doi:10.17583/rimcis.7096

19. Niemz, K, Griffiths, M, and Banyard, P. Prevalence of Pathological Internet Use Among University Students and Correlations with Self-Esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and Disinhibition. Cyberpsychol Behav (2005) 8(6):562–70. doi:10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562

20. Widyanto, L, and Griffiths, M. An Empirical Study of Problematic Internet Use and Self-Esteem. Int J Cyber Behav Psychol Learn IJCBPL (2011) 1(1):13–24. doi:10.4018/ijcbpl.2011010102

21. Park, S, Kang, M, and Kim, E. Social Relationship on Problematic Internet Use (PIU) Among Adolescents in South Korea: A Moderated Mediation Model of Self-Esteem and Self-Control. Comput Hum Behav (2014) 38:349–57. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.005

22. Yao, MZ, He, J, Ko, DM, and Pang, K. The Influence of Personality, Parental Behaviors, and Self-Esteem on Internet Addiction: A Study of Chinese College Students. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw (2014) 17(2):104–10. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0710

23. Naseri, L, Mohamadi, J, Sayehmiri, K, and Azizpoor, Y. Perceived Social Support, Self-Esteem, and Internet Addiction Among Students of Al-Zahra University, Tehran, Iran. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci (2015) 9(3):e421. doi:10.17795/ijpbs-421

24. Mei, S, Yau, YHC, Chai, J, Guo, J, and Potenza, MN. Problematic Internet Use, Well-Being, Self-Esteem and Self-Control: Data from a High-School Survey in China. Addict Behav (2016) 61:74–9. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.009

25. Seabra, L, Loureiro, M, Pereira, H, Monteiro, S, Marina Afonso, R, and Esgalhado, G. Relationship between Internet Addiction and Self-Esteem: Cross-Cultural Study in Portugal and Brazil. Interact Comput (2017) 29(5):767–78. doi:10.1093/iwc/iwx011

26. Ko, CH, Yen, JY, Yen, CF, Lin, HC, and Yang, MJ. Factors Predictive for Incidence and Remission of Internet Addiction in Young Adolescents: A Prospective Study. Cyberpsychol Behav (2007) 10(4):545–51. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.9992

27. Griffiths, M. Does Internet and Computer" Addiction" Exist? Some Case Study Evidence. CyberPsychol Behav (2000) 3(2):211–8. doi:10.1089/109493100316067

28. Kristjánsson, K. On the Very Idea of “Negative Emotions”. J Theor Soc Behav (2003) 33(4):351–64. doi:10.1046/j.1468-5914.2003.00222.x

29. Tannenbaum, LE, Forehand, R, and Thomas, AM. Adolescent Self-Reported Anxiety and Depression: Separate Constructs or a Single Entity. Child Study J (1992) 22:61–72.

30. Wang, JS, Qiu, BW, and He, ES. Study on the Relationship between Depression and Anxiety of Middle School Students. Adv Psychol Sci (1998) 3(4):62–5.

31. Berryhill, MB, and Smith, J. College Student Chaotically-Disengaged Family Functioning, Depression, and Anxiety: The Indirect Effects of Positive Family Communication and Self-Compassion. Marriage Fam Rev (2021) 57(1):1–23. doi:10.1080/01494929.2020.1740373

32. Hu, M, Xu, L, Zhu, W, Zhang, T, Wang, Q, Ai, Z, et al. The Influence of Childhood Trauma and Family Functioning on Internet Addiction in Adolescents: A Chain-Mediated Model Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2022) 19(20):13639. doi:10.3390/ijerph192013639

33. Liu, Y, Wang, Q, Zhou, WH, Yao, XM, Fang, ZH, Ihsan, A, et al. Application of a Modified Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for 3-Amino-2-Oxazolidinone Residue in Aquatic Animals. Chin J Drug Abuse Prev Treat (2010) 664(03):151–7. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2010.02.010

34. Kouros, CD, and Garber, J. Trajectories of Individual Depressive Symptoms in Adolescents: Gender and Family Relationships as Predictors. Dev Psychol (2014) 50:2633–43. doi:10.1037/a0038190

35. Zhang, H, and Wang, J. Influence of Parental Marital Status and Family Atmosphere on the Adolescent Depressive Symptoms and the Moder-Ating Function of Character Strengths. Guangdong Med J (2017) 38(4):598–603.

36. Sela, Y, Zach, M, Amichay-Hamburger, Y, Mishali, M, and Omer, H. Family Environment and Problematic Internet Use Among Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Depression and Fear of Missing Out. Comput Hum Behav (2020) 106:106226. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.106226

37. Cole, SH, and Hooley, JM. Clinical and Personality Correlates of MMO Gaming: Anxiety and Absorption in Problematic Internet Use. Soc Sci Comput Rev (2013) 31(4):424–36. doi:10.1177/0894439312475280

38. Marciano, L, Schulz, PJ, and Camerini, AL. How Do Depression, Duration of Internet Use and Social Connection in Adolescence Influence Each Other over Time? an Extension of the RI-CLPM Including Contextual Factors. Comput Hum Behav (2022) 136:107390. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2022.107390

39. Li, G, Hou, G, Yang, D, Jian, H, and Wang, W. Relationship between Anxiety, Depression, Sex, Obesity, and Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents: A Short-Term Longitudinal Study. Addict Behav (2019) 90:421–7. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.009

40. Orvaschel, H, Beeferman, D, and Kabacoff, R. Depression, Self-Esteem, Sex, and Age in a Child and Adolescent Clinical Sample. J Clin Child Psychol (1997) 26(3):285–9. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_7

41. Leary, MR, Schreindorfer, LS, and Haupt, AL. The Role of Low Self-Esteem in Emotional and Behavioral Problems: Why Is Low Self-Esteem Dysfunctional? In: The Interface of Social and Clinical Psychology: Key Readings. Key readings in social psychology. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press (2004). p. 116–28.

42. Ozyesil, Z. The Prediction Level of Self-Esteem on Humor Style and Positive-Negative Affect. Psychology (2012) 03(08):638–41. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.38098

43. Brown, JD, and Marshall, MA. Self-Esteem and Emotion: Some Thoughts about Feelings. Pers Soc Psychol Bull (2001) 27(5):575–84. doi:10.1177/0146167201275006

44. Sowislo, JF, and Orth, U. Does Low Self-Esteem Predict Depression and Anxiety? A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol Bull (2013) 139:213–40. doi:10.1037/a0028931

45. Axelson, DA, and Birmaher, B. Relation between Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Depress Anxiety (2001) 14(2):67–78. doi:10.1002/da.1048

46. Belzer, K, and Schneier, FR. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders: Issues in Conceptualization, Assessment, and Treatment. J Psychiatr Pract (2004) 10(5):296–306. doi:10.1097/00131746-200409000-00003

47. Jacobson, NC, and Newman, MG. Anxiety and Depression as Bidirectional Risk Factors for One Another: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol Bull (2017) 143:1155–200. doi:10.1037/bul0000111

48. Darwin, C. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. In: Ekman P, editor. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. 3rd ed., xxxvi. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press (1872). p. 472.

49. Alloy, LB, Kelly, KA, Mineka, S, and Clements, CM. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders: A Helplessness-Hopelessness Perspective. In: Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Association (1990). p. 499–543.

50. Zhang, Q, Wang, Y, Yuan, CY, Zhang, XH, and Li, YJ. The Gender Effect on the Relationship between Internet Addiction and Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol (2014) 22(6):1004–9.

51. Yang, JZ, Kang, CY, and Zhao, XD. The Self-Rating Inventory of Systematic Family Dynamics: Development, Reliability and Validity. Chin J Clin Psychol (2002) 10(4):263–5.

52. Yang, YF, Liang, Y, and Zhang, YH. Revision, Reliability and Validity Evaluation of Self-Rating Scale of Systemic Family Dynamics-Students Testing Version. Chin J Public Health (2016) 32(2):4.

54. Zung, WWK. A Self-Rating Depression Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1965) 12(1):63–70. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008

55. Yong, . Caught in the Net. Available from: https://sc.panda321.com/extdomains/books.google.com/books/about/Caught_in_the_Net.html?hl=zh-CN&id=kfFk8-GZPD0C (Accessed November 20, 2022 ).

56. Bao, Z, Zhang, W, Li, D, and Wang, Y. School Climate and Academic Achievement Among Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model. Psychol Dev Educ (2013) 29:61–70.

57. Little, RJA, and Rubin, DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons (2019). p. 462.

58. Hayes, AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford publications (2017).

59. Shrout, PE, and Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol Methods (2002) 7(4):422–45. doi:10.1037/1082-989x.7.4.422

60. Schneider, LA, King, DL, and Delfabbro, PH. Family Factors in Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming: A Systematic Review. J Behav Addict (2017) 6(3):321–33. doi:10.1556/2006.6.2017.035

61. Zhang, W, Pu, J, He, R, Yu, M, Xu, L, He, X, et al. Demographic Characteristics, Family Environment and Psychosocial Factors Affecting Internet Addiction in Chinese Adolescents. J Affect Disord (2022) 315:130–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.053

62. Shek, DTL. A Longitudinal Study of the Relationship between Family Functioning and Adolescent Psychological Well-Being. J Youth Stud (1998) 1(2):195–209. doi:10.1080/13676261.1998.10593006

63. Kingon, YS, and O’Sullivan, AL. The Family as a Protective Asset in Adolescent Development. J Holist Nurs (2001) 19(2):102–21. doi:10.1177/089801010101900202

64. Yen, JY, Yen, CF, Chen, CC, Chen, SH, and Ko, CH. Family Factors of Internet Addiction and Substance Use Experience in Taiwanese Adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav (2007) 10(3):323–9. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9948

65. Park, N, Kee, KF, and Valenzuela, S. Being Immersed in Social Networking Environment: Facebook Groups, Uses and Gratifications, and Social Outcomes. Cyberpsychol Behav (2009) 12(6):729–33. doi:10.1089/cpb.2009.0003

66. Wąsiński, A, and Tomczyk, Ł. Factors Reducing the Risk of Internet Addiction in Young People in Their home Environment. Child Youth Serv Rev (2015) 57:68–74. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.022

67. Leary, MR, and Downs, DL. Interpersonal Functions of the Self-Esteem Motive. In: Kernis MH, editor. Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem. The Springer Series in Social Clinical Psychology. Boston, MA: Springer US (1995). p. 123–44. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1280-0_7

68. Krauss, S, Orth, U, and Robins, RW. Family Environment and Self-Esteem Development: A Longitudinal Study from Age 10 to 16. J Pers Soc Psychol (2020) 119:457–78. doi:10.1037/pspp0000263

69. Davis, RA. A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of Pathological Internet Use. Comput Hum Behav (2001) 17(2):187–95. doi:10.1016/s0747-5632(00)00041-8

70. Hall, NC, Jackson Gradt, SE, Goetz, T, and Musu-Gillette, LE. Attributional Retraining, Self-Esteem, and the Job Interview: Benefits and Risks for College Student Employment. J Exp Educ (2011) 79(3):318–39. doi:10.1080/00220973.2010.503247

71. Washington, T, Rose, T, Coard, SI, Patton, DU, Young, S, Giles, S, et al. Family-Level Factors, Depression, and Anxiety Among African American Children: A Systematic Review. Child Youth Care Forum (2017) 46(1):137–56. doi:10.1007/s10566-016-9372-z

72. Luebbe, AM, and Bell, DJ. Positive and Negative Family Emotional Climate Differentially Predict Youth Anxiety and Depression via Distinct Affective Pathways. J Abnorm Child Psychol (2014) 42(6):897–911. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9838-5

73. Boumosleh, JM, and Jaalouk, D. Depression, Anxiety, and Smartphone Addiction in university Students- A Cross Sectional Study. PLOS ONE (2017) 12(8):e0182239. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182239

74. Cummings, CM, Caporino, NE, and Kendall, PC. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: 20 Years after. Psychol Bull (2014) 140:816–45. doi:10.1037/a0034733

75. Epkins, CC, and Heckler, DR. Integrating Etiological Models of Social Anxiety and Depression in Youth: Evidence for a Cumulative Interpersonal Risk Model. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev (2011) 14(4):329–76. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0101-8

76. Deleuze, J, Maurage, P, Schimmenti, A, Nuyens, F, Melzer, A, and Billieux, J. Escaping Reality through Videogames Is Linked to an Implicit Preference for Virtual over Real-Life Stimuli. J Affect Disord (2019) 245:1024–31. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.078

77. Whang, LSM, Lee, S, and Chang, G. Internet Over-users’ Psychological Profiles: A Behavior Sampling Analysis on Internet Addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav (2003) 6(2):143–50. doi:10.1089/109493103321640338

78. Cottrell, D, and Boston, P. Practitioner Review: The Effectiveness of Systemic Family Therapy for Children and Adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (2002) 43(5):573–86. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00047

79. McWey, LM. Systemic Family Therapy with Children and Adolescents. In: The Handbook of Systemic Family Therapy. John Wiley & Sons (2020). p. 732.

80. Young, KS. CBT-IA: The First Treatment Model for Internet Addiction. J Cogn Psychother (2011) 25(4):304–12. doi:10.1891/0889-8391.25.4.304

81. Dusong, Y, Jiang, W, and Vance, A. Longer Term Effect of Randomized, Controlled Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Internet Addiction in Adolescent Students in Shanghai. Aust N Z J Psychiatry (2010) 44(2):129–34. doi:10.3109/00048670903282725

82. Iveson, C. Solution-focused Brief Therapy. Adv Psychiatr Treat (2002) 8(2):149–56. doi:10.1192/apt.8.2.149

83. Kim, JS, and Franklin, C. Solution-focused Brief Therapy in Schools: A Review of the Outcome Literature. Child Youth Serv Rev (2009) 31(4):464–70. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.10.002

84. Machimbarrena, JM, Calvete, E, Fernández-González, L, Álvarez-Bardón, A, Álvarez-Fernández, L, and González-Cabrera, J. Internet Risks: An Overview of Victimization in Cyberbullying, Cyber Dating Abuse, Sexting, Online Grooming and Problematic Internet Use. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(11):2471. doi:10.3390/ijerph15112471

Keywords: negative emotion, internet addiction, self-esteem, family atmosphere, chain mediation model

Citation: Shi Y, Tang Z, Gan Z, Hu M and Liu Y (2023) Association Between Family Atmosphere and Internet Addiction Among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Negative Emotions. Int J Public Health 68:1605609. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2023.1605609

Received: 21 November 2022; Accepted: 14 June 2023;

Published: 26 June 2023.

Edited by:

Daniela Husarova, University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik Kosice, SlovakiaReviewed by:

Yu-Te Huang, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaJoanna Mazur, University of Zielona Góra, Poland

Copyright © 2023 Shi, Tang, Gan, Hu and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yang Liu, yliux@outlook.com

Yijian Shi

Yijian Shi Zijun Tang

Zijun Tang Zhilin Gan

Zhilin Gan Manji Hu

Manji Hu Yang Liu

Yang Liu