- 1Institute of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine, Université de Genève, Geneva, Switzerland

- 2Research for Impact Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 3School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines

Objective: To provide a comparative analysis of current tobacco and alcohol control laws and policies in the Philippines and Singapore

Methods: We used a public health law framework that incorporates a systems approach using a scorecard to assess the progress of the Philippines and Singapore in tobacco and alcohol control according to SDG indicators, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and the WHO Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol. We collected data from the scientific literature and government documents.

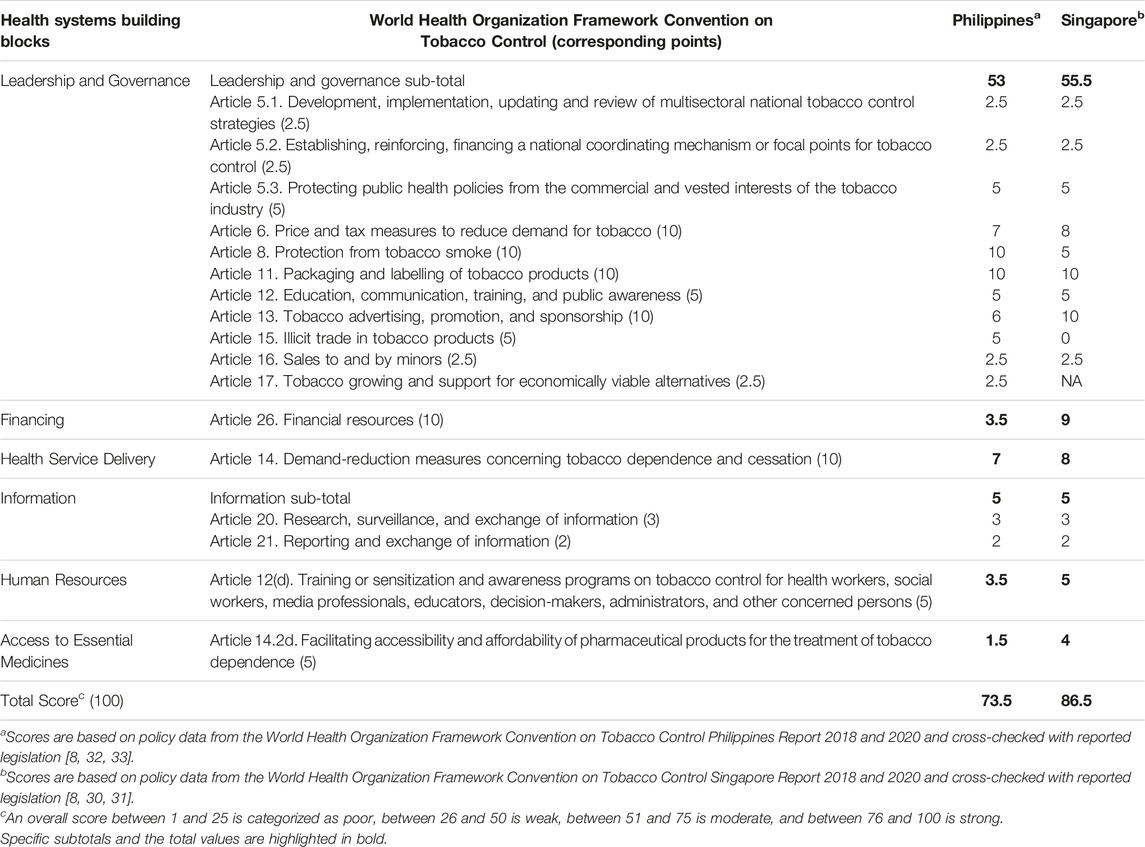

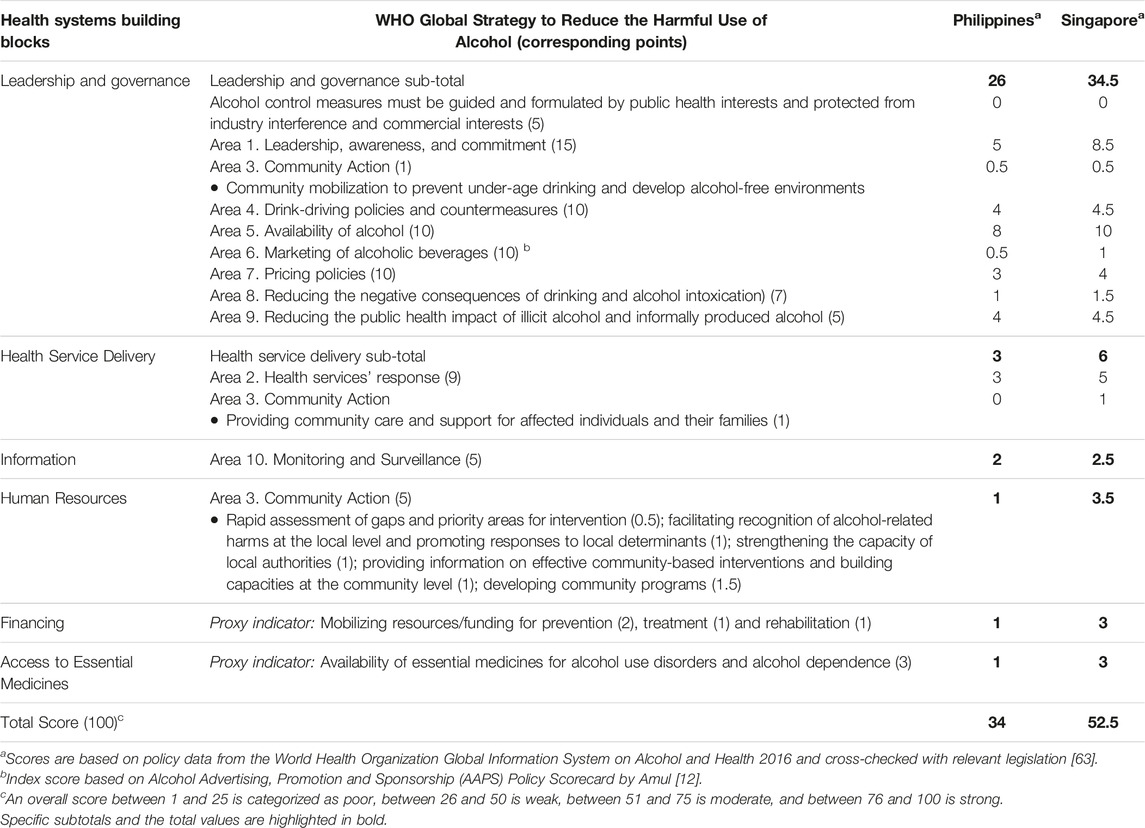

Results: Despite health system differences, both the Philippines (73.5) and Singapore (86.5) scored high for tobacco control, but both countries received weak and moderate scores for alcohol control: the Philippines (34) and Singapore (52.5). Both countries have policy avenues to reinforce restrictions on marketing and corporate social responsibility programs, protect policies from the influence of the industry, and reinforce tobacco cessation and preventive measures against alcohol harms.

Conclusion: Using a health system-based scorecard for policy surveillance in alcohol and tobacco control helped set policy benchmarks, showed the gaps and opportunities in these two countries, and identified avenues for strengthening current policies.

Introduction

The burden of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) is now pervasive in both high-income and low- and middle-income economies. In a high-income country like Singapore, NCDs account for an estimated 84% of the burden of disease and about 83% of deaths, and even in a lower-middle-income country like the Philippines, NCDs already account for more than 64% of the burden of disease and 70% of deaths [1]. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, tobacco and alcohol use remained the top risk factors for disease and death burden in the Philippines and Singapore since 1990, for both males and females [2]. When disaggregated by gender, males bear a higher tobacco-attributable and alcohol-attributable burden of disease than females in both the Philippines and Singapore [2].

From a global health perspective, the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has been a powerful legal framework and a foundation for the development and implementation of tobacco control policies in countries at various economic development levels [3, 4]. While tobacco control implementation has been assessed using the World Bank’s Tobacco Control Scale, the WHO FCTC and health systems frameworks, alcohol control policies vis-à-vis the WHO Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol (Global Alcohol Strategy hereafter) have yet to be assessed using a systems perspective [5–9].

The methods of public health law, including policy surveillance, have also been used to assess tobacco and alcohol measures, and have been invariably adopted by the WHO in monitoring international health law, including the FCTC [10, 11]. Despite the growth in comparative mechanisms, alcohol policy surveillance has yet to be institutionally adapted for the rigorous evaluation of legislation for alcohol control in any of the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The Philippines and Singapore offer case studies of two different health systems in ASEAN with recent reforms in their tobacco and alcohol control policies. While both countries face the increasing burden of NCDs and the expansion of the alcohol and tobacco industry [12], both countries offer policy lessons on alcohol and tobacco control towards the development of a regional framework for alcohol control [13].

This study aims to provide a comparative analysis of tobacco and alcohol policies in the Philippines and Singapore from a public health law and systems approach. This study offers a comparative policy surveillance framework that acknowledges the complexity of both alcohol and tobacco control and assesses countries on their progress in tobacco and alcohol control beyond demand and supply-reduction measures, by looking into the WHO health system building blocks—with particular focus on leadership and governance, financing, human resources, information, service delivery and access to essential medicines [8].

Methods

We used a systems approach to develop a scorecard measuring the progress of the Philippines and Singapore in tobacco and alcohol control, based on the WHO’s health system’s six building blocks (leadership and governance, financing, human resources, information, service delivery and medical products and technologies) vis-à-vis Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Health and Well-Being) outcome indicators, the FCTC, and the Global Alcohol Strategy [14–17].

We drew on methodology from transdisciplinary public health law, particularly policy surveillance, which involves the empirical tracking of law and policies of disease, and global health law which focuses on international law and health [11, 18].

For the policy surveillance, we conducted an online document search to include official English versions of policy documents (legislation, implementing rules and subsidiary regulations and related guidelines specific to tobacco and alcohol) and reports from the websites of the WHO, websites of various Philippine and Singapore government agencies and online policy databases. Both the Philippines and Singapore use English as one of their official languages. These were cross-checked with official English versions in the Singapore Statutes Online and in the Philippines’ Official Gazette available online. We supplemented this with reports in English from non-governmental organisations, corporate documents and news articles.

Additionally, we supplemented this with a review of the peer-reviewed literature in English on PubMed published from January 2009 to December 2020. Please see Supplementary Figure S1 for the search strategy. We included articles that specifically refer to alcohol and tobacco policies in the Philippines and Singapore. We excluded epidemiological, clinical, and behavioural studies with no reference to alcohol or tobacco policies in the Philippines and Singapore.

Scorecard

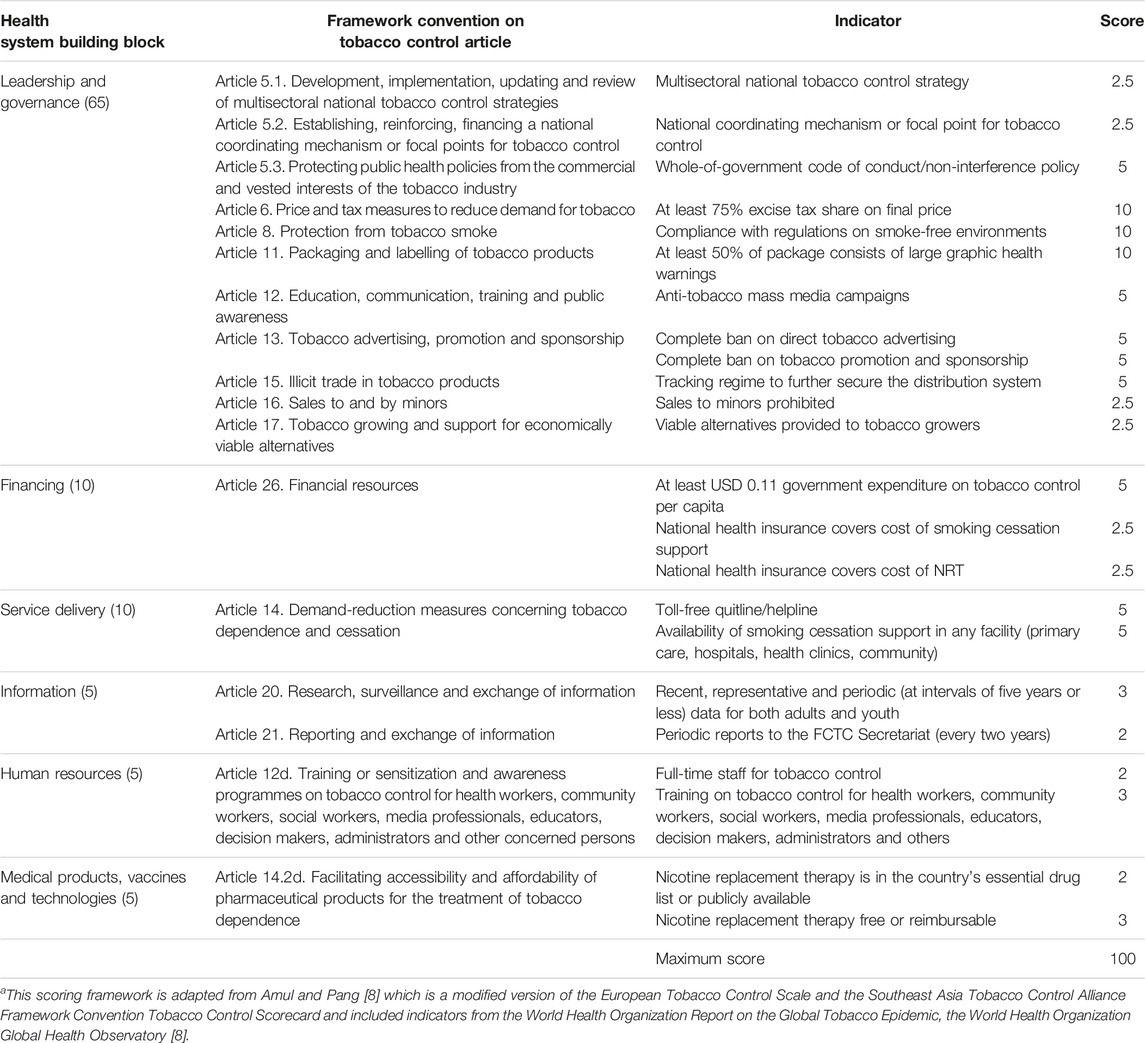

We adapted the tobacco control scorecard and the indicators developed by Amul and Pang [8]. They assessed the implementation of tobacco control using the health system building blocks by assigning scores for each article in the WHO FCTC, with the highest scores (10 points) allotted for MPOWER measures which include monitoring tobacco use, protecting people from tobacco smoke, offering help to quit tobacco, warning about the dangers of tobacco, enforcing tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) bans, and raising taxes on tobacco (See Table 1). The scorecard incorporated indicators from the FCTC Implementation Database and the WHO Global Health Observatory.

TABLE 1. Scoring framework for the tobacco control scorecard based on the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control according to the health system building blocks (Singapore and the Philippines, 2022)a.

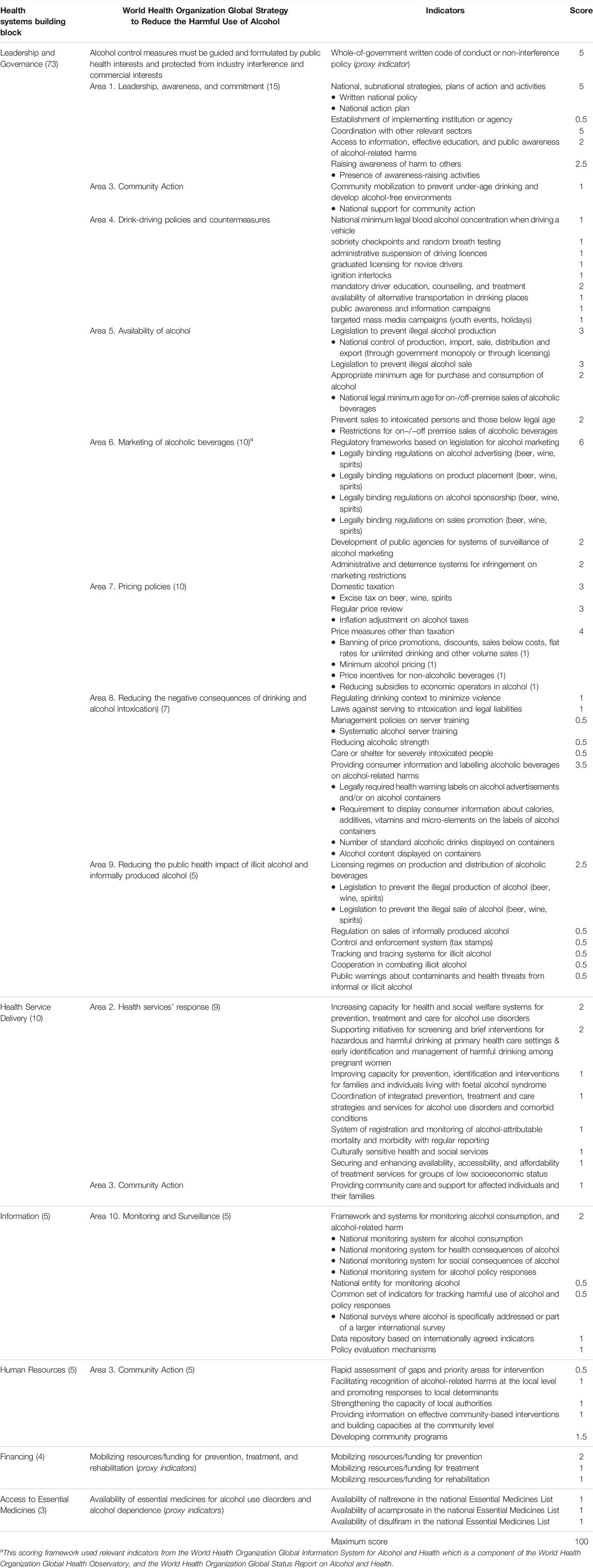

Existing alcohol policy assessment tools focused only on five domains—physical availability, drinking context, alcohol prices, alcohol advertising and drivers of motor vehicles [19–21]. A detailed AAPS policy scorecard for Southeast Asia is also incorporated into the scorecard for alcohol control policies [12]. For the alcohol control scorecard, we incorporated indicators and also compiled policy data (where available) from the WHO Global Information System for Alcohol and Health, and the country profiles in the most recent WHO Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health [22, 23]. We assigned scores for each policy recommendation in the Global Alcohol Strategy, with the highest scores (10 points) allotted for measures in the WHO SAFER Initiative (SAFER) [24]. These policies included restrictions on alcohol availability, drink-driving countermeasures, access to screening, brief interventions and treatment, restrictions on alcohol advertising, promotion and sponsorship (AAPS), and raising alcohol prices through excise taxes and other pricing policies [24] (See Table 2).

TABLE 2. Scoring framework for the alcohol control scorecard based on the World Health Organization Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol according to the health systems building blocks (Singapore and the Philippines, 2022)a.

To incorporate policies that go beyond the health system for implementation and enforcement including taxation, illicit trade, marketing restrictions, community action, smoke-free environments, and drunk-driving countermeasures, we adapted the concept of health system governance as a process that involves “ensuring strategic policy frameworks exist and are combined with effective oversight, coalition-building, regulation, attention to system design and accountability” and is determined by the interaction of the State, health service providers, and citizens [25]. Additionally, we also adapted the principle of health in all policies which recognize “the policy practice of including, integrating or internalizing health in other policies that shape or influence the social determinants of health [26]”.

GGA devised the scoring system based on an existing tobacco control scorecard which used the WHO health system building blocks as a framework [8]. GGA compiled the policy data from the document search and allotted the scores for each country. Based on the results of the document search for policy data, GGA generated the scores for each policy in each country based on the extracted policy data. Each indicator has allotted points and when there are policy data that meets the indicator’s full scope, a full score is tabulated for that indicator. When the policy only covers a partial scope of the indicator, the tally of points scored for each partial scope is tabulated. When there is no policy for that indicator, no points are tabulated for that indicator. Total scores for both the tobacco and alcohol control scorecard range from 0 to 100. An overall score between 1 and 25 is categorized as poor, between 26 and 50 is weak, between 51 and 75 is moderate, and between 76 and 100 is strong.

Tables 1, 2 show the breakdown of the indicators and the scoring system used in this study. There were fewer data sources for alcohol control than for tobacco control, and where data is not available, we used proxy indicators for financing and access to essential medicines.

Results

In the peer-reviewed literature, we found 93 articles on tobacco control and 94 articles on alcohol control in the Philippines, and 200 articles on tobacco control and 139 articles on alcohol control in Singapore. We used Endnote to compile all search results for various combinations of the search terms and removed duplicates using the ‘find duplicates’ function; after screening the remaining 211 titles and abstracts for articles using the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria, we retained 24 articles on Singapore and 17 articles on the Philippines for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis.

Combining results from the literature and policy data from the document search, the next section offers a snapshot of the policy framework for alcohol and tobacco control in each country, followed by a narrative synthesis based on each country’s strengths and gaps in the health system building blocks, and a discussion on avenues of intervention for both countries.

Policy Framework

The Philippines and Singapore are both parties to the FCTC and both have selectively implemented some policy recommendations from the Global Alcohol Strategy [15, 16, 27]. However, both countries have yet to ratify the FCTC Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products (hereafter “Protocol on illicit trade’’), which came into force in 2018, and they have not yet announced any plans to do so [28]. Table 3 and the following sections show that both countries have implemented most of the WHO FCTC measures [29–32]. Table 4 shows that both countries have implemented only a selection of recommendations from the Global Alcohol Strategy, with a particular focus on alcohol taxation and drunk-driving prevention measures [22]. Both countries implement surveillance on tobacco use; both participate in the Global Tobacco Surveillance System [33]. Both countries also report to the WHO for the Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, albeit these reports show limited surveillance in both prevalence and policy [22]. Tables 3, 4 also show that the Philippines has strong tobacco control, but weak alcohol control. Singapore scored strongly on all health system building blocks for tobacco control but obtained moderate scores for alcohol control.

TABLE 3. Tobacco control score card for the Philippines and Singapore, based on the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control with the health systems building blocks as a framework (Philippines and Singapore, 2020).

TABLE 4. Alcohol control score card for the Philippines and Singapore, based on the World Health Organization Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol with the health systems building blocks as a framework (Philippines and Singapore, 2020).

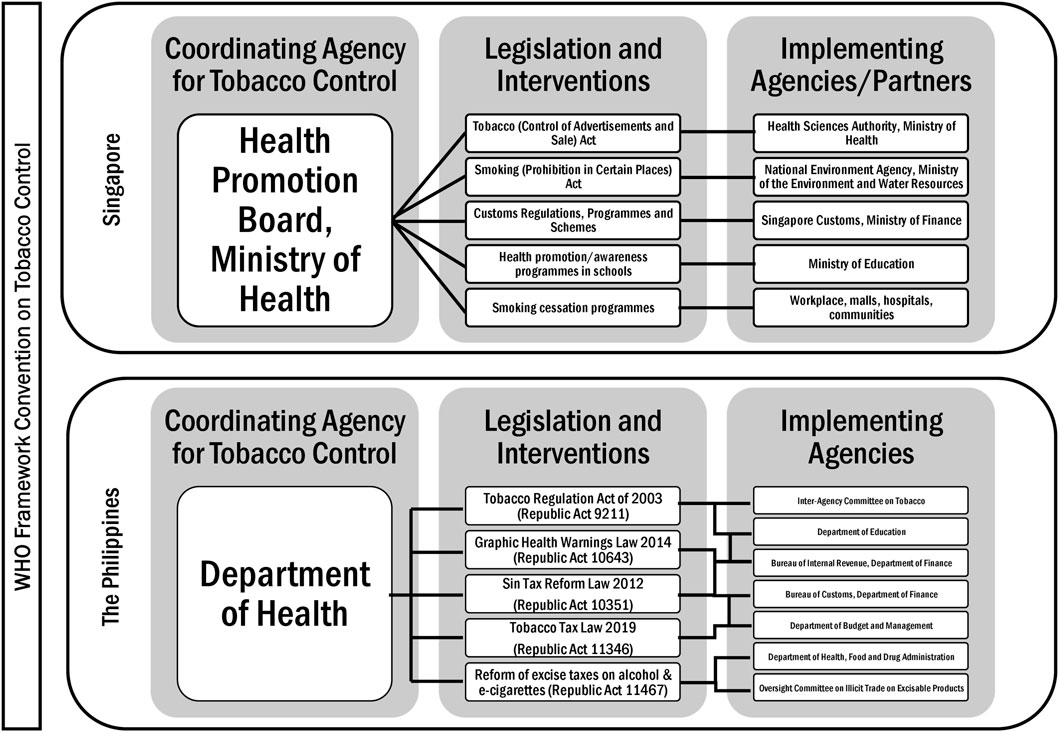

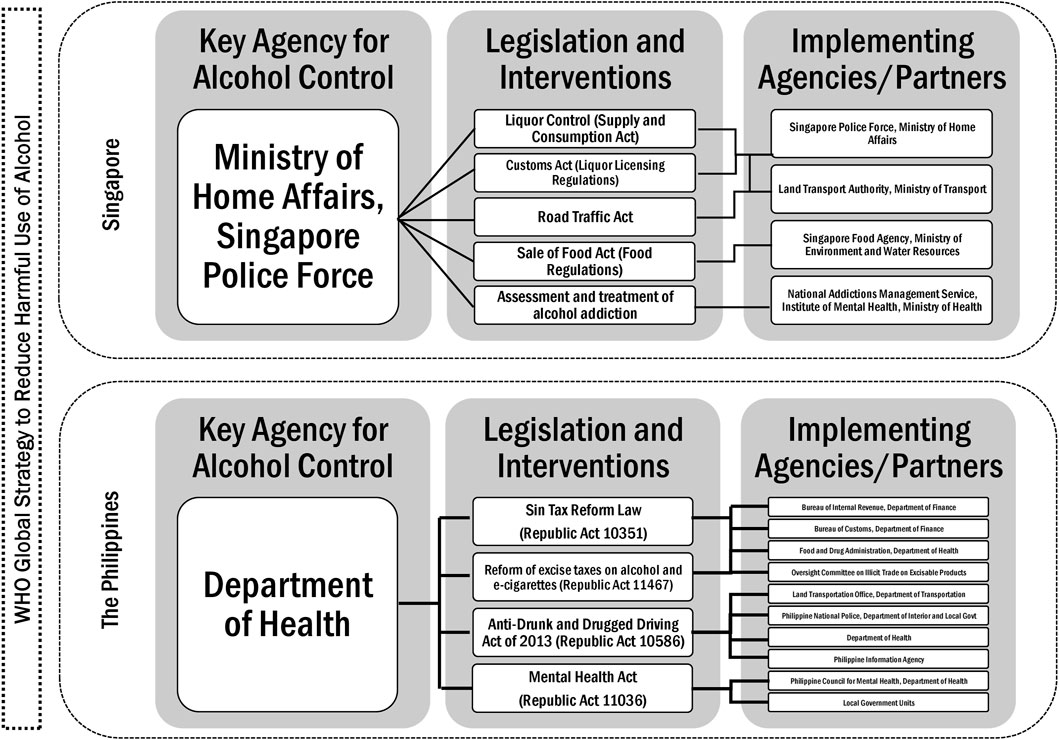

Singapore is historically a strong authoritarian state, and this translates to strong political will and leadership in terms of tobacco control, which began in the 1970s, while alcohol control has mainly been focused on price measures, including taxes and tariffs (Supplementary Table S1), and recently on reducing accessibility, with licensing (Supplementary Table S3), no-liquor zones and sale restrictions, and increasing penalties for drunk driving [34–36]. Figure 1 presents the laws and implementing agencies that govern tobacco control policies in the Philippines and Singapore [37]. Only in the past decade did the Philippine government (particularly the Presidency) show leadership in terms of both tobacco and alcohol control, with consecutive reforms on alcohol taxation and anti-drunk driving laws (Supplementary Tables S2, S4) [38]. Figure 2 shows the legislation and responsible agencies that implement the policies for alcohol control in the Philippines and Singapore [39].

Strengths in Tobacco Control

Table 3 shows that both countries score relatively high on the tobacco control scorecard, but that Singapore (86.5) scored higher than the Philippines (76.5). Singapore’s strengths lie in the strict enforcement of its tobacco control policies including tobacco taxation policies, financing of health promotion, smoke-free policies, a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (TAPS hereafter), packaging and labelling measures (standardised packaging), and access to essential medicines and therapies for tobacco cessation [37, 40] (Table 3). Singapore adjusts its tax rates according to inflation, and it increased its tobacco tax rate to 67.5% in 2018, while it increased alcohol tax rates to SGD88 per litre in 2014 [41]. Singapore has comprehensively banned advertising, promotion, and sponsorship of tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) [42]. Singapore has also progressively raised the minimum legal age for smoking to 21 years [43] and banned the import, distribution, sale or offer for sale of cigarette packs that contain less than 20 sticks, and it does not have any duty-free concessions or goods and services tax relief for cigarettes [37, 44].

Both countries have implemented several measures in compliance with the FCTC article on illicit trade, including the Singapore Duty-Paid Cigarette (SDPC) markings and the Philippines’ tax stamps under the Internal Revenue Stamps Integrated System (IRSIS) to be affixed on all unit packets of cigarettes and alcohol products in 2018 [8, 37].

Singapore also scores high in terms of access to essential medicines, and nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion and varenicline (medications to treat tobacco dependence) are part of Singapore’s essential medicines list (EML), while only varenicline is part of the Philippines’ EML [45, 46]. Nicotine replacement therapy is free or reimbursable through the public health sector in Singapore but not in the Philippines [8, 40]. Singapore’s Health Promotion Board implements public education campaigns that complement multi-sectoral and community-based national smoking cessation programmes [47].

The Philippines’ strengths in tobacco control lie in its tobacco taxation policies (Supplementary Table S1) and its explicit policy of protecting the public administration from tobacco industry interference [48, 49] (Table 3). The Philippines’ recent tax reforms have set tax rates that increase every year from 2020 to 2024, after which tax rates are set to increase annually by 5% for tobacco products and 6% for alcohol products [38].

Gaps in Tobacco Control

Singapore’s weakness in tobacco control lies in the lack of explicit, publicly available guidelines to protect public policies from industry interference, despite the city-state’s otherwise strong anti-corruption measures. Singapore implements a “government-wide code of conduct and internal guidelines for relevant agencies’ governing interaction with the tobacco industry,” but there is no publicly available written policy about these guidelines [30]. Additionally, Singapore’s Prevention of Corruption Act covers such interactions in both the public and private sectors [50].

The Philippines’ key weakness in tobacco control lies in the inclusion of the tobacco industry in the Philippines’ Inter-Agency Committee on Tobacco because this creates a conflict of interest. The Philippines became a party to the FCTC only after legislation established this tobacco control policy-making committee that includes the tobacco industry, which is an infringement of Article 5.3 of the FCTC that obligates the Philippines as a party to the FCTC to protect tobacco control policies from commercial interests of the tobacco industry [51].

Additionally, both countries have weaknesses in terms of illicit tobacco trade control, and both have yet to ratify the FCTC Protocol on illicit trade. The Philippines has less comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions, and there are still loopholes for the protection against advertising and promotion, especially at the point of sale, which the tobacco industry exploits [52]. Moreover, the Philippines still tolerates sales of single-stick cigarettes, although the law requires that cigarettes be sold in 20-cigarette packs [53]. Furthermore, the Philippines still allows duty-free concessions on tobacco products [8].

The two countries vary in their approach to electronic nicotine delivery devices (ENDS), with Singapore being comprehensively restrictive—banning emerging and alternative nicotine products, while the Philippines preferred regulation through taxation [32].

Strengths in Alcohol Control

Singapore (52.5) scored higher than the Philippines (34) on the alcohol control scorecard (Table 4). As shown in Table 4, despite a marked difference in financing capacities, the strengths of Singapore’s alcohol control measures lie in an array of tax measures, licensing regime, restrictions in availability (minimum legal age, zoning, and time of sale), access to essential medicines, and drunk driving prevention measures. Singapore scores high on access to essential medicines for alcohol use disorders. The most common medications for alcohol use disorders and alcohol dependence—naltrexone, acamprosate and disulfiram are available on prescription in Singapore, but not subsidised [54, 55]. Moreover, Singapore’s National Addictions Management Service offers a helpline for those seeking help with their alcohol addiction and runs an inpatient facility and treatment services for adolescents with substance abuse issues [56, 57].

As with tobacco control, the strength of the Philippines’ alcohol control measures particularly lies in its alcohol taxation policy [48]. For tracking and tracing the products (a measure against illicit trade), the Philippines also requires import permits and tax stamps on imported alcoholic beverages. In 2019, to protect children, the government issued guidelines on the commercial display at point-of-sale, and on the sale, promotion, and advertising of alcoholic beverages [58]. In terms of licensing, both Singapore and the Philippines have retail licensing regimes for alcohol, but only Singapore has retail licensing regimes for both tobacco and alcohol.

Gaps in Alcohol Control

Despite the socio-economic differences between them, both countries share weaknesses in alcohol policies. First, both lack comprehensive and legally binding regulations on alcohol advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; both Singapore and the Philippines have voluntary industry measures that are known to be ineffective and thus both countries have poor scores in policies to regulate alcohol marketing [12] (Table 4).

Second, Singapore and the Philippines also score low on alcohol pricing policies with the lack of minimum pricing, lower pricing of non-alcoholic beverages, below-cost and volume discounts ban, or added levy on specific products. Both countries still have duty-free concessions on alcohol at 2 L per person per trip.

Third, both do not have specific and written guidelines on interaction with the alcohol industry to protect policies from commercial interests, a key element of SAFER [24]. Moreover, despite the conflict of interest, both countries’ governments still engage in public-private partnerships (PPPs) with the alcohol industry and promote the alcohol industry’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes [12].

Fourth, Table 4 also shows that both countries still lack measures that help inform the public about alcohol harms on alcohol product packaging and labelling. The Philippines even lacks harmonization of its alcohol labelling regulations to apply for both local and imported alcoholic beverages [12].

Fifth, the Philippines’ lower scores on alcohol control can be attributed in part to the low access to essential medicines for the treatment of alcohol use disorders, as only naltrexone is listed in its EML [46].

Sixth, both countries have similarly low scores on information because of the lack of a national system for monitoring and surveillance of alcohol harms, despite having national surveys on youth and adult alcohol consumption. Singapore has a national system of epidemiological data collection for alcohol use and health service delivery, but the Philippines does not have any of the two; both do not report data from health services on alcohol use and alcohol use disorders.

Seventh, the Philippines scores low (3) in health service response to harmful alcohol use because of the slow implementation of policies which mandate prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation for alcohol use disorders at the community level [53]. There is room to enhance health service delivery for alcohol use disorders, especially with the predominant public-private referral system for treatment and rehabilitation services for alcohol addiction. In a country of about 100 million, there are only 13 private rehabilitation facilities and one government-run rehabilitation centre for alcohol dependence and alcohol addiction [59].

Finally, as a high-income economy with a developed health system, Singapore does not earmark taxes on tobacco and alcohol for prevention and control measures of these products. However, it has invested in health promotion with an average annual budget of SGD186 million (USD133 million) from 2009 to 2019 [37, 60]. On the other hand, as a lower-middle-income economy, the Philippines, with the 2019 tax reforms (Supplementary Table S4), has earmarked revenue from taxes on alcohol, tobacco, heated tobacco and vapour products, and sweetened alcoholic beverages to fulfil its universal health coverage goals (60%), health infrastructure development (20%), and the SDGs (20%) [48].

Earmarking tax revenue for healthcare from 2004 led to a substantive increase in the Department of Health’s budget, explained by an 87.5% increase in excise tax revenue from alcohol and tobacco from 2015 to 2019 [48, 61]. However, the Philippines still has a low score in financing tobacco and alcohol control because the taxes are not earmarked for this purpose.

Discussion

In this study, we described the strengths and weaknesses of tobacco and alcohol control policies in Singapore and the Philippines, using the WHO’s health system building blocks as a framework for analysis. Singapore has always considered tobacco control a critical concern for public health, but alcohol control remains primarily an issue of public order and road safety rather than a public health issue. As shown in the policy framework for alcohol control in Singapore in Figure 2, the key agency for alcohol control is the Singapore Police Force, not the Ministry of Health. In the Philippines, while both alcohol and tobacco control are on the public health agenda, alcohol control policies are reliant on alcohol taxes aimed at revenue generation for universal health coverage. The scorecard shows that when assessed by health system building blocks, most of the alcohol control policies in the Philippines are weak, except when recent tax reforms led to an increase in alcohol taxes earmarked for healthcare.

Various tobacco control scorecards have been used to track the implementation of the FCTC, but assessments of alcohol control policies are less comprehensive [9, 62, 63]. This study’s originality lies in its use of health systems as a framework to assess alcohol control policies in two diverse countries [64].

Avenues for Intervention

The results of the health system scorecard analysis for alcohol and tobacco control suggest various avenues for intervention. First, leadership and governance are critical in tobacco and alcohol control, as the effective implementation of the FCTC and the Global Alcohol Strategy relies on concrete, legally binding and enforceable policy measures [65]. This calls for stronger engagement of various actors—intergovernmental organizations, global health networks, non-government organizations, community organizations, and the academe—to work with governments to pursue, promote and support the implementation of stronger alcohol and tobacco control policies.

Second, given the pervasiveness of self-regulation for the alcohol industry in the Philippines and Singapore and the lack of marketing restrictions, the political influence of the alcohol industry merits a better response from policymakers. This is possible and has been done in Europe and the Americas [12, 66]. This calls for policy approaches that capture the commercial determinants of health [67].

Third, a look into the global policy environment is necessary. While the FCTC requires parties to allot funding for tobacco control, there is no similar financing recommendation for the implementation of the WHO Global Alcohol Strategy. This creates a funding gap for implementing alcohol control policies, in both the Philippines and Singapore.

The two countries diverge in their approach to ENDS with prohibition in Singapore and regulation in the Philippines. While there is initially strong regulation on the minimum legal age of use of ENDS in the Philippines at 21, recent legislation lowered this age to 18, the same minimum legal age for cigarette use in the country. This stands in contrast to the minimum legal age in Singapore where the minimum legal age for the purchase, use, possession, sale, and supply of cigarettes was raised to 21 [43].

The Global Alcohol Strategy is not legally binding, but its policy recommendations are cost-effective and are included in the WHO’s Best Buys for NCDs which includes alcohol and tobacco control measures [68]. These evidence-based and cost-effective measures are encapsulated in the WHO’s SAFER initiative, through which the country cases were assessed in this study but have yet to be adopted and implemented globally [24].

However, governance and leadership are hindered by policymakers’ lack of recognition of emerging but preventable public health issues. For example, while recent studies have pointed out the problem of binge drinking in Singapore, there have been no attempts to assess the potential of legally binding policies that can help prevent, if not minimize, the harmful effects of binge drinking, not only to the consumer but also to others around them, beyond increasing penalties for violating drunk driving regulations [69, 70]. Both countries are still hindered by a disease-based model for policymaking for NCDs instead of a risk-based public health model that is focused on disease prevention and health promotion [71].

The SDGs, the FCTC and the Global Alcohol Strategy provide a distinct policy window for further integration of disease prevention and health promotion not only in tobacco control but also in alcohol control. The relevant literature from low- and middle-income economies points out how interventions focused more on the detection and treatment of alcohol dependence rather than on harmful alcohol use, which is responsible for more alcohol-related harm, lead to delayed identification and care for harmful and hazardous drinkers [72]. Treatment gaps for alcohol use disorders even in a high-income economy like Singapore are due to delayed identification of the cases, often exacerbated by stigma [73].

An opportunity that both countries should consider is on implementing legally binding restrictions and regulations on AAPS, CSR and PPPs. There is pending legislation in the Philippines promoting and financially incentivizing CSR with no restrictions to health harmful industries, which has drawn opposition from public health advocates [74]. However, there is no robust evidence that the alcohol industry’s CSR initiatives aimed at reducing harmful drinking contribute to such goals and further complicated by a conflict of interest [74–76]. Such policy blind spots increase the alcohol industry’s power and influence, which are still evident even in institutions of global health governance [77].

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of its findings. It does not attempt to comparatively assess policy outcomes, stringency or effectiveness. Moreover, this study cannot provide a basis to generalize tobacco and alcohol control policies across middle- and high-income countries because of the small number of countries that were included for comparison.

Conclusion

This study shows that using a health system-based scorecard for policy surveillance in alcohol and tobacco control can help set policy benchmarks, show the gaps and opportunities, and contribute to strengthening current policies. By using a public health law framework to assess tobacco and alcohol policies, we also identified neglected and new avenues for interventions. These opportunities include additional restrictions and regulations on alcohol marketing, financing of prevention (not just treatment) of tobacco and alcohol harms, and measures to protect policies from industry interference.

This in-depth comparative case study of two countries can be a useful framework to assess tobacco and alcohol control in other countries at various stages of economic and health system development. This study also provides opportunities for policymakers to assess a country’s progress over time vis-à-vis its national health agenda and global voluntary targets.

Author Contributions

GGA conceptualized and designed the study, collected, and analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J-FE contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. GGA and J-FE provided approval for the version of the manuscript submitted for publication. GGA and J-FE agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

The authors received no external financial support for the research and authorship of this article. The Swiss School of Public Health (SSPH+) covered part of the publication charges. SSPH+ was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication. The University of Geneva paid JFE’s salary and also part of the publication charges. GGA also paid part of the publication charges.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2022.1605050/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Global Health Data Exchange. GBD Results Tool. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (2018). Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool (Accessed November 1, 2020).

2. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. GBD Compare, Viz Hub (2021). Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/(Accessed March 2, 2021).

3. Craig, L, Fong, GT, Chung-Hall, J, and Puska, P. Impact of the WHO FCTC on Tobacco Control: Perspectives from Stakeholders in 12 Countries. Tob Control (2019) 28(2):s129–35. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054940

4. Zhou, SY, Liberman, JD, and Ricafort, E. The Impact of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in Defending Legal Challenges to Tobacco Control Measures. Tob Control (2019) 28(2):s113–8. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054329

5. World Health Organization. MPOWER: A Policy Package to Reverse the Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization (2008). Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/mpower_english.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

6. Joossens, L, and Raw, M. The Tobacco Control Scale: a New Scale to Measure Country Activity. Tob Control (2006) 15(3):247–53. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.015347

7. Levy, DT, Yuan, Z, Luo, Y, and Mays, D. Seven Years of Progress in Tobacco Control: an Evaluation of the Effect of Nations Meeting the Highest Level MPOWER Measures between 2007 and 2014. Tob Control (2018) 27(1):50–7. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053381

8. Amul, GGH, and Pang, T. The State of Tobacco Control in ASEAN: Framing the Implementation of the FCTC from a Health Systems Perspective. Asia Pac Pol Stud (2018) 5(1):47–64. doi:10.1002/app5.218

9. Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance. Seatca Fctc Scorecard: Measuring Implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Bangkok, Thailand: Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (2016). Available from: https://seatca.org/dmdocuments/SEATCA/FCTC/Scorecard.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

10. Marks-Sultan, G, Tsai, F-j, Anderson, E, Kastler, F, Sprumont, D, and Burris, S. National Public Health Law: a Role for WHO in Capacity-Building and Promoting Transparency. Bull World Health Organ (2016) 94(7):534–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.164749

11. Burris, S, Ashe, M, Levin, D, Penn, M, and Larkin, M. A Transdisciplinary Approach to Public Health Law: The Emerging Practice of Legal Epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health (2016) 37:135–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021841

12. Amul, GGH. Alcohol Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship: A Review of Regulatory Policies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. J Stud Alcohol Drugs (2020) 81(6):697–709. doi:10.15288/jsad.2020.81.697

13. ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Health Cluster 1: Promoting Healthy Lifestyle. Revised Work Programme (2017). Available from: https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Agd-8.3_1.-ASEAN-Health-Cluster-1-Work-Programme_Endorsed-SOMHD.pdf (Accessed November 1, 2020).

14. United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015). Available from: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (Accessed November 1, 2019).

15. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization (2005). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/50793/retrieve (Accessed November 1, 2019).

16. World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Reduce Harmful Use of Alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010). Available from: https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/alcstratenglishfinal.pdf (Accessed November 1, 2019).

17. World Health Organization. Everybody's Business -- Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO's Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization (2007). Available from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf (Accessed November 1, 2019).

18. Gostin, LO, Monahan, JT, Kaldor, J, DeBartolo, M, Friedman, EA, Gottschalk, K, et al. The Legal Determinants of Health: Harnessing the Power of Law for Global Health and Sustainable Development. Lancet (2019) 393(10183):1857–910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30233-8

19. Carragher, N, Byrnes, J, Doran, CM, and Shakeshaft, A. Developing an Alcohol Policy Assessment Toolkit: Application in the Western Pacific. Bull World Health Organ (2014) 92(10):726–33. doi:10.2471/BLT.13.130708

20. Casswell, S, Morojele, N, Williams, PP, Chaiyasong, S, Gordon, R, Gray-Phillip, G, et al. The Alcohol Environment Protocol: A New Tool for Alcohol Policy. Drug Alcohol Rev (2018) 37(S2):S18–S26. doi:10.1111/dar.12654

21. Brand, DA, Saisana, M, Rynn, LA, Pennoni, F, and Lowenfels, AB. Comparative Analysis of Alcohol Control Policies in 30 Countries. Plos Med (2007) 4(4):e151. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040151

22. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018). https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1151838/retrieve (Accessed February 1, 2019).

23. Drope, J, Schluger, N, Cahn, Z, Hamill, S, Islami, F, Liber, A, et al. The Tobacco Atlas (2018). Available from: https://tobaccoatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/TobaccoAtlas_6thEdition_LoRes_Rev0318.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2019).

24. World Health Organization. SAFER: A World Free from Alcohol Related Harms. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2018). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329931 (Accessed February 1, 2019).

25. World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization (2007). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43918/1/9789241596077_eng.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2019).

26. McQueen, DV, Wismar, M, Lin, V, Jones, CM, and Davies, M. In: Intersectoral Governance for Health in All Policies: Structures, Actions and Experiences. Geneva: World Health Organization on behalf od the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2012). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1241778/retrieve (Accessed February 1, 2022).

27. United Nations. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. New York: Treaty Series: United Nations (2005). p. 166. Available from: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IX-4&chapter=9&clang=_en (Accessed November 1, 2020).

28. WHO FCTC. Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/284810/retrieve (Accessed February 1, 2019).

29. WHO FCTC Secretariat. Core Questionnaire of the Reporting Instrument of WHO FCTC - Singapore (2020). Available from: https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/wp-content/uploads/Singapore_2020_WHOFCTCreport.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2021).

30. WHO FCTC Secretariat. Core Questionnaire of the Reporting Instrument of WHO FCTC – Singapore (2018). Available from: https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/wp-content/uploads/Singapore_2018_report.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

31. WHO FCTC Secretariat. Core Questionnaire of the Reporting Instrument of WHO FCTC - Philippines (2018). Available from: https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/wp-content/uploads/Philippines_2018_report.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

32. WHO FCTC Secretariat. Core Questionnaire of the Reporting Instrument of WHO FCTC - Philippines (2020). Available from: https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/wp-content/uploads/Philippines_2020_WHOFCTCreport.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2021).

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global Tobacco Control, about Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data (GTSSData). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2021). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gtss/gtssdata/index.html (Accessed November 1, 2021).

34. Singapore Police Force. Overview of Liquor Licence (2020). Available from: https://www.police.gov.sg/e-Services/Police-Licences/Liquor-Licence (Accessed February 1, 2021).

35. Singapore Police Force. Extension of Trading Hours for Liquor and Beer Deliveries Made to Non-public Places: Frequently Asked Questions (2020). Available from: https://www.police.gov.sg/-/media/Spf/Images/Licences/Liquor-Licence-Exemption-FAQs.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2021).

36. Singapore Police Force. Liquor Licence: Types of Liquor Licence and Fees (2020). Available from: https://www.police.gov.sg/e-Services/Police-Licences/Liquor-Licence (Accessed February 1, 2021).

37. Amul, GGH, and Pang, T. Progress in Tobacco Control in Singapore: Lessons and Challenges in the Implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Asia Pac Pol Stud (2018) 5(1):102–21. doi:10.1002/app5.222

38. Congress of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 11467 (2019). Available from: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/01jan/20200122-RA-11467-RRD.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2020).

39. Congress of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 7160 (1991). Available from: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1991/10/10/republic-act-no-7160/ (Accessed December 1, 2020).

40. Teo, J. Parliament: Smokers to Get Subsidies for Nicotine Replacement Therapy. The Straits Times, March 5, 2020 (2020). Available from: https://str.sg/Jxk9 (Accessed March 31, 2020).

41. Singapore Customs. Change in Liquor Tax Rates. INSYNC, Issue 2. Singapore Customs (2008). Available from: https://www.customs.gov.sg/-/media/cus/files/insync/issue02/updates/liquor.html (Accessed February 1, 2020).

42. Health Sciences Authority Singapore. Overview of Tobacco Control: Regulatory Overview: Key Tobacco Control Laws (2019). Available from: https://www.hsa.gov.sg/tobacco-regulation/overview (Accessed February 1, 2020).

43. Ministry of Health Singapore. Minimum Legal Age for Tobacco Raised to 21 Years Old from January 2021, 30. December: Ministry of Health Singapore (2020). p. 2020. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/minimum-legal-age-for-tobacco-raised-to-21-years-old-from-1-january-2021 (Accessed February 1, 2021).

44. Tobacco (Control of Advertisement and Sale) (Licensing) Regulations. Singapore Statutes Online (2017). Available from: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/SL/TCASA1993-S763-2017?DocDate=20181221 (Accessed February 1, 2020).

45. Health Promotion Board Singapore. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Health Promotion Board-Ministry of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines 1/2013. Health Promotion Board (2013). Available from: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/pdf/hpb-moh-clinical-practice-guidelines-treating-tobacco-use-and-dependence-2013.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2020).

46. Department of Health Philippines. Philippine National Formulary, 8th Ed. (2019). Available from: https://pharma.doh.gov.ph/the-philippine-national-formulary/(Accessed February 1, 2020).

47. Health Promotion Board Singapore. Many Pathways to a Healthy Nation: Annual Report 2018/2019. Singapore: Health Promotion Board Singapore (2019). Available from: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/annual-reports/hpb-annual-report-2018_2019.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2020).

48. Kaiser, K, Bredenkamp, C, and Iglesias, R. Sin Tax Reform in the Philippines: Transforming Public Finance, Health, and Governance for More Inclusive Development. Washington, DC: World Bank Group (2016). Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/638391468480878595/Sin-tax-reform-in-the-Philippines-transforming-public-finance-health-and-governance-for-more-inclusive-development (Accessed December 1, 2019).

49. Assunta, M, and Dorotheo, EU. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: a Tool for Measuring Implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Tob Control (2016) 25(3):313–8. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051934

50. Prevention of Corruption Act. 1960, Revised 1993. Singapore Statutes Online (2021). Available from: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/PCA1960 (Accessed December 22, 2021).

51. Lencucha, R, Drope, J, and Chavez, JJ. Whole-of-government Approaches to NCDs: the Case of the Philippines Interagency Committee-Tobacco. Health Policy Plan (2015) 30(7):844–52. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu085

52. Amul, GGH, Tan, GPP, and van der Eijk, Y. A Systematic Review of Tobacco Industry Tactics in Southeast Asia: Lessons for Other Low- and Middle-Income Regions. Int J Health Pol Manag (2021) 10(6):324–37. doi:10.34172/IJHPM.2020.97

53. Congress of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 11346 (2018). Available from: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2019/07/25/republic-act-no-11346/ (Accessed December 1, 2019).

54. Institute of Mental Health Singapore. Patient Information Leaflet on Naltrexone (2012). Available from: https://www.pss.org.sg/sites/default/files/public-resource/pil-naltrexone_edited.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

55. Ministry of Health Singapore. Drug Food Administration Instructions (2022). Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/default-document-library/drug-food-admin-instructions-(15-feb-2022).xlsx?sfvrsn=4e38a173_0 (Accessed March 1, 2022).

56. National Addictions Management Service Singapore. Our Services/Inpatient Detoxification (2020). Available from: https://www.nams.sg/our-services/Pages/inpatient-detoxification.aspx (Accessed February 1, 2021).

57. National Addictions Management Service Singapore. Our Services/ReLive - Clinic for Adolescents (2020). Available from: https://www.nams.sg/our-services/relive/Pages/default.aspx (Accessed February 1, 2021).

58. Food and Drug Administration Philippines. Food and Drug Administration Circular No. 2019-006 - Guidelines in Commercial Display, Selling, Promotion and Advertising of Alcoholic Beverages and Beverages that Contain Alcohol (2019). Available from: https://www.fda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FDA-Circular-No.2019-006.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2019).

59. RehabPath Philippines. Find a Rehab Center in the Philippines (2020). Available from: https://rehabs.ph/ (Accessed December 1, 2020).

60. Ministry of Finance Singapore. Singapore Budget. Singapore: Ministry of Health (2009). Available from: https://www.mof.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/singapore-budget/budget-archives/2009/fy2009_revenue_expenditure.zip (Accessed December 1, 2020).

61. Department of Finance Philippines. Sin' Tax Collections Almost Double to P269.1-B in 2019. February 21 (2020). Available from: https://taxreform.dof.gov.ph/news_and_updates/sin-tax-collections-almost-double-to-p269-1-b-in-2019/ (Accessed December 1, 2020).

62. World Health Organization. Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (2018). Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.GISAH?lang=en (Accessed February 1, 2020).

63. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Southeast Asia. Making South-East Asia SAFER from Alcohol-Related Harm: Current Status and Way Forward (2019). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326535 (Accessed February 1, 2020).

64. Petticrew, M, Shemilt, I, Lorenc, T, Marteau, TM, Melendez-Torres, GJ, Mara-Eves, A, et al. Alcohol Advertising and Public Health: Systems Perspectives versus Narrow Perspectives. J Epidemiol Community Health (2017) 71(3):308–12. doi:10.1136/jech-2016-207644

65. Au Yeung, SL, and Lam, TH. Unite for a Framework Convention for Alcohol Control. Lancet (2019) 393:1778–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32214-1

66. Noel, JK, Babor, TF, and Robaina, K. Industry Self-Regulation of Alcohol Marketing: a Systematic Review of Content and Exposure Research. Addiction (2017) 112(S1):28–50. doi:10.1111/add.13410

67. World Health Organization. Commercial Determinants of Health. WHO Fact Sheets. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health (Accessed November 10, 2021).

68. World Health Organization. Tackling NCDs: 'best Buys' and Other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases (2017). Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232 (Accessed February 1, 2019).

69. Lee, YY, Wang, P, Abdin, E, Chang, S, Shafie, S, Sambasivam, R, et al. Prevalence of Binge Drinking and its Association with Mental Health Conditions and Quality of Life in Singapore. Addict Behav (2020) 100:106114. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106114

70. Lim, W-Y, Fong, CW, Chan, JML, Heng, D, Bhalla, V, and Chew, SK. Trends in Alcohol Consumption in Singapore 1992–2004. Alcohol Alcohol (2007) 42(4):354–61. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agm017

71. Butler, S, Elmeland, K, Nicholls, J, and Thom, B. Alcohol, Power and Public Health: A Comparative Study of Alcohol Policy. London and New York: Routledge (2017). p. 214.

72. Benegal, V, Chand, PK, and Obot, IS. Packages of Care for Alcohol Use Disorders in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Plos Med (2009) 6(10):e1000170. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000170

73. Subramaniam, M, Abdin, E, Vaingankar, JA, Shafie, S, Chua, HC, Tan, WM, et al. Minding the Treatment gap: Results of the Singapore Mental Health Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2020) 55(11):1415–24. doi:10.1007/s00127-019-01748-0

74. Fonacier, K, and Manongdo, P. Is the Philippines' CSR Bill a Trojan Horse for Corporate Interests? Eco-Business (2021). Available from: https://www.eco-business.com/news/is-the-philippines-csr-bill-a-trojan-horse-for-corporate-interests/ (Accessed June 30, 2021).

75. Mialon, M, and McCambridge, J. Alcohol Industry Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives and Harmful Drinking: a Systematic Review. Eur J Public Health (2018) 28(4):664–73. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky065

76. Collin, J. Taking Steps toward Coherent Global Governance of Alcohol: The Challenge and Opportunity of Managing Conflict of Interest. J Stud Alcohol Drugs (2021) 82(3):387–94. doi:10.15288/jsad.2021.82.387

Keywords: tobacco control, health systems, alcohol control, Philippines, Singapore, health policy, public health law, policy surveillance

Citation: Amul GGH and Etter J-F (2022) Comparing Tobacco and Alcohol Policies From a Health Systems Perspective: The Cases of the Philippines and Singapore. Int J Public Health 67:1605050. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1605050

Received: 06 May 2022; Accepted: 09 September 2022;

Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited by:

Nino Kuenzli, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Cuong Pham, Hanoi University of Public Health, VietnamCopyright © 2022 Amul and Etter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gianna Gayle Herrera Amul, R2lhbm5hLkFtdWxAZXR1LnVuaWdlLmNo

Gianna Gayle Herrera Amul

Gianna Gayle Herrera Amul Jean-Francois Etter

Jean-Francois Etter