- 1Ningbo Kangning Hospital, Ningbo, China

- 2Ningbo Medical Centre Li Huili Hospital, Ningbo, China

Objective: Parental and peer support are both associated with mental distress and unhealthy behaviour indices in adolescents.

Methods: We used the Global School-Based Student Health Survey data (n = 192,633) from 53 countries and calculated the weighted prevalence of individual and combined parental and peer support. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the adjusted associations between combined parental and peer support with mental distress and unhealthy behaviours.

Results: The prevalence figures for having all four categories of parental support and two peer-support were 9.7% and 38.4%, respectively. Compared with no parental support, adolescents with all four parental support negatively associated with all five mental distress and eight unhealthy behaviours factors, and the ORs ranged from 0.19 to 0.75. Additionally, adolescents with two peer support were negative association with all mental distress and four health risk behaviours, and positively associated with a sedentary lifestyle.

Conclusion: Parental and peer support were lacking in some countries, while greater parental and peer support were negative associated with mental distress and most unhealthy behaviours in adolescents, and the relationships were independent.

Introduction

Adolescents represent nearly a quarter of the world’s population, and approximately 90% live in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). Adolescence is a vital period in life—with changes in physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development [1], and families exert the primary influence on child development [2]. Family support—such as parental respect and attention—is the most important factor that protects against poor health outcomes in adolescents by helping them adopt effective measures to cope with stress and adverse life events [3]. Adolescents might, as a result, drive toward self-involvement and independence, and tend to make friends and rely on them [1]. Therefore, friendships are also very important to the health of adolescents.

Mental distress was shown to be prevalent in adolescents [4], especially in LMICs. Half of mental health distress in adulthood starts by age 14, but most cases go undetected [5]. A study of LMICs showed that the overall pooled prevalence of anxiety in 82 countries was 9.0% (7.0%–12.0%) [6]. Unhealthy behaviours (tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, and physical inactivity) contribute to the incidence of non-communicable diseases in adults, and increase the short-term or long-term likelihood of morbidity and mortality [7]. For example, in individuals older than 60 years of age, tobacco use accounted for 10% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), alcohol use for 7%, marijuana use for 2%, and physical inactivity accounted for 7% [8]. Premature sexual activity contributes to epidemics of HPV and HIV, and can result in adolescent pregnancy that affects adolescents’ present and future health, and accounts for 4% of DALYs [8]. The reduction in mental distress and unhealthy behaviours is thus important in improving childhood development.

Previous studies that explored individual parental and peer support all entailed protective factors related to some mental distress and unhealthy behaviours in LMICs [6, 9–11]. Moreover, in some developed countries adolescents who reported more family connections also delayed sexual initiation and exhibited lower levels of substance use [3, 12]. However, investigators have not previously been able to examine the effects of combined parental support (where parents checked homework, understood problems, concerned with adolescent free time, and where parents respected privacy) and peer support (having close friendships and supportive classmates)—all of which concentrates on investigating the relationship between individual parental or peer support and mental health factors.

In order to help shape adolescent mental distress and unhealthy behaviour-prevention strategies, we investigated the associations between a comprehensive panel of parental and peer support with mental distress and unhealthy behaviours using 53 country-representative samples from the GSHS—varying in gender, World Bank country-income classification, and WHO regions.

Methods

Data Sources

We used the publicly available data from the GSHS. GSHS is a self-administered, school-based survey jointly developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The details of the survey methodology and questionnaires can be found at the websites of the WHO and CDC (http://www.who.int/chp/gshs and http://www.cdc.gov/gshs, respectively). The primary aim of the GSHS was to assess and quantify the risks and protective factors involved in major non-communicable diseases—including alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, hygienic practices, sexual behaviours, mental health, violence, and unintentional injury [13]. The survey uses a standardized two-stage probability sampling design for the selection process within each participating country. In the first stage, schools were randomly sampled from all schools in the country according to probability proportional to size sampling. In the second stage, classes with targeted-age students in each selected school were randomly sampled from systematic equal-probability sampling. All students in the selected class were then ultimately eligible to participate in the survey [13], and all data collection was performed during regular class time. The questionnaire was translated into the local language of each country and finished by students using a self-report, computer-scannable form. All GSHS surveys were approved by the Ministry of Health or Education and Ethics Committee, and informed consent was received from students, parents, and/or school officials, where necessary.

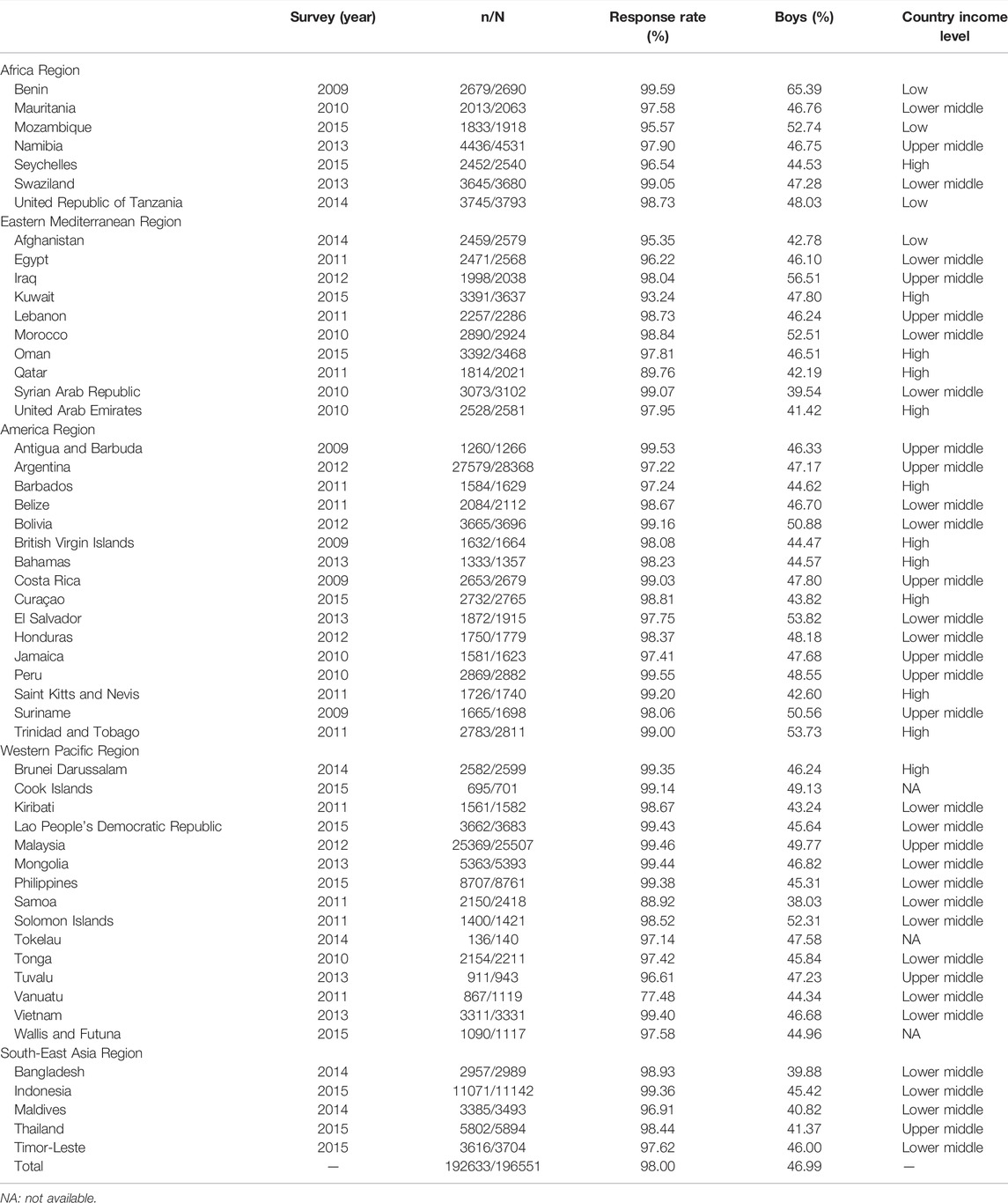

We selected nationally representative datasets that included all parental and peer-support variables. The GSHS entailed three historical surveys, such that if a particular country already had two or more datasets, we chose the most recent dataset. Finally, a total of 53 countries with the survey conducted between 2009 and 2015 were included in the current study. Our study populations restricted to in-school adolescents for aged 13–17 years. The corresponding country-income levels of the included countries were also obtained based on their World Bank classifications at the time the survey was conducted [14]. The detailed characteristics of included countries are listed in Table 1.

Measures

Parental and Peer Support

Parental support was assessed by four components (parents checked homework, parents understood problems, parents concerned free time, and parents respected for privacy). “Parents checked homework” was examined with the question “Percentage of students whose parents or guardians check to see if your homework was done most of the time or always during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no”. “Parents understood problems” was examined with the question “Percentage of students whose parents or guardians understand your problems and worry most of the time or always during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no”. “Parents concerned free time” was examined with the question “Percentage of students whose parents or guardians really know what you were doing with your free time most of the time or always during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no.” “Parental respect for privacy” was examined with the question, “Percentage of students whose parents or guardians go through your things without your approval never or rarely during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no.” Peer support was assessed by two components (close friendships and supportive classmates). “Close friendships” was examined with the question “Percentage of students who had no close friends?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no”. “Supportive classmates” was examined with the question “Percentage of students who reported most of the students in your school as kind and helpful most of the time or always during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no” (Supplementary Table S1). An individual answering “yes” meant a question score of 1; otherwise, the score was 0—except for the question of close friendships, where the answer “yes” meant a score of 0. The combined parental and peer support of the young adolescents was calculated by summing the aforementioned four parental support question scores and the two peer support question scores.

Mental Health Factors

We also selected five mental health outcome variables to evaluate their associations with parental and peer support. These were loneliness (yes, no), insomnia due to anxiety (yes, no), suicidal ideation (yes, no), suicidal planning (yes, no), and suicide attempts (yes, no). The completed questions regarding mental health factors, their answers, and coding are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Health Risk Behaviours

We also selected eight health-risk behaviour outcome variables to evaluate their associations with parental and peer support. These were violence (yes, no), hygienic practices (yes, no), premature sexual activities (yes, no), current tobacco use (yes, no), current alcohol use (yes, no), current marijuana use (yes, no), sedentary lifestyle (yes, no), and school truancy (yes, no). The completed questions regarding health-risk behaviours, their answers, and coding are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Confunding Factors

We also selected age, sex, BMI and hunger status as confunding factors. Hunger status was examined with the question “Percentage of students who went hungry most of the time or always because there was not enough food in your home during the past 30 days?” with a binary response of “yes” or “no,” and hunger status was defined as socioeconomic status of adolescents family.

Statistical Analyses

The frequencies of individual and combined parental and peer support were based on individual data from each country survey, and we calculated the overall prevalence of individual and combined parental and peer support for all participants. As the GSHS uses a complex sampling design, data analyses should take this into account. We thus calculated the weighted prevalence estimates and corresponding 95% CIs using the SURVEYMEANS procedure in SAS (version 9.4). We added weights, stratum, and a primary sampling unit (PSU) to every school-attending child to reflect the weighting process and the two-stage sampling design. The weighting allowed the results to be generalized to the study population and the national student population, the stratum reflected the first stage of the GSHS sampling (at the school level), and the PSU reflected the second stage (the classroom level).

Pooled regional and country-income levels and overall estimates were calculated by random-effects meta-analysis using STATA (version 12.0), and we used the I2 statistic to estimate heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were stratified by gender (boys vs. girls). We used logistic regression models to analyse the relationships between combined parental and peer support and mental health factors and health risk behaviours, adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and food insecurity. The food insecurity variable was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) [15]. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States) and STATA version 12.0 (Stata Corporation; College Station, TX, United States) were used to perform statistical analyses.

Results

Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the survey and participants from the included GSHS datasets. Ultimately, fifty-three countries or regions were included from five WHO regions: 7 from the African Region; 10 from the Eastern Mediterranean Region; 16 from the Region of the Americas; 15 from the Western Pacific Region; and 5 from the South-East Asia Region (Supplementary Figure S1). According to the World Bank country-income classification based upon the years of the survey, included surveys were categorized into 4 low-income countries, 22 lower middle-income countries, 12 upper middle-income countries, 12 high-income countries, and 3 countries or regions with no classification information in the World Bank. This distribution corresponded to a total of 192,633 young adolescents who attended school (46.99% boys and 53.01% girls) in our analysis. The median sample size for each country was 2471 (1665–3391), and the overall response rate was 98.00% (range, 77.48%–99.57%).

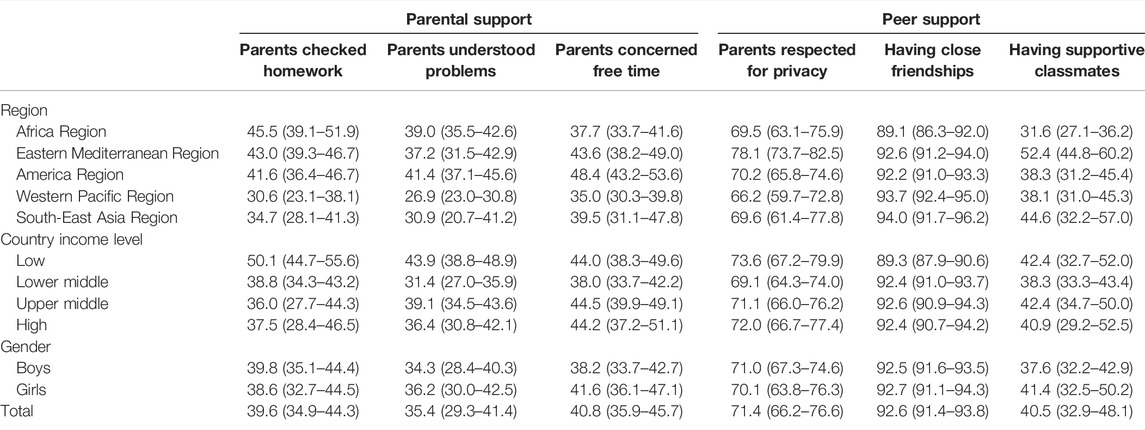

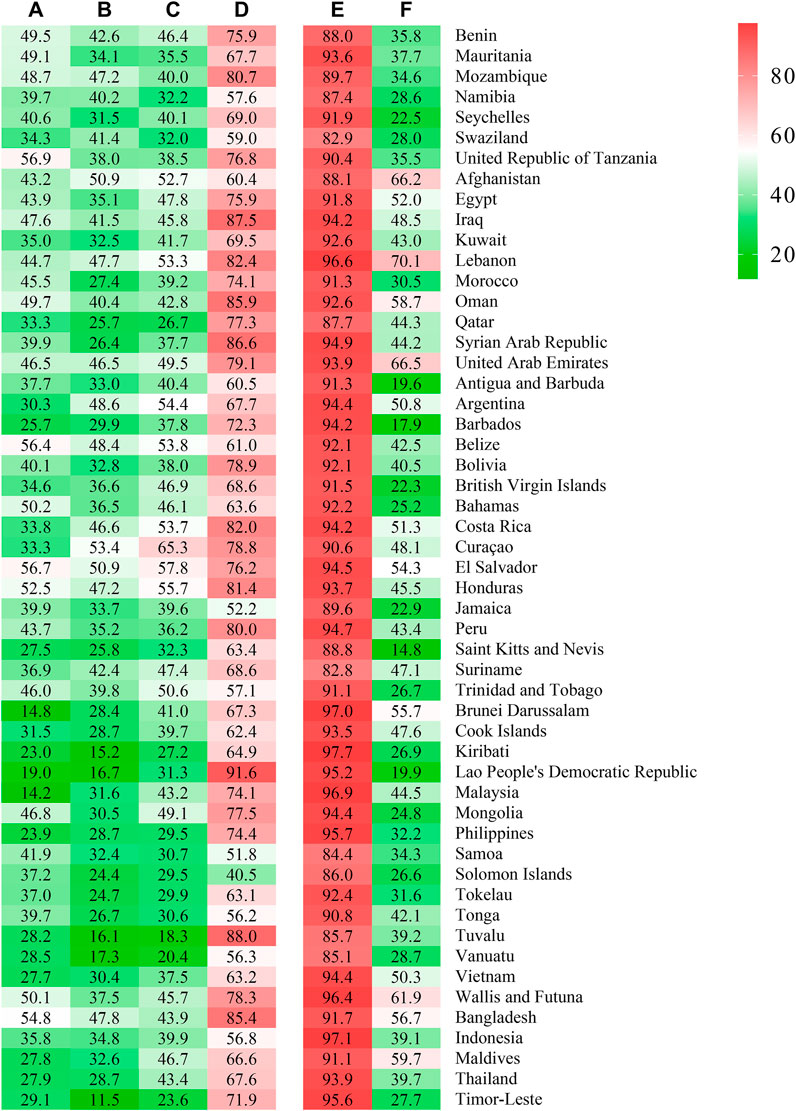

The overall prevalence of the categories parents checked homework, parents understood problems, parents concerned free time, and parents respected for privacy was 39.6%, 35.4%, 40.8%, and 71.4%, respectively (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). There were 92.6% of school-attending adolescents who reported having one or more close friends and 40.5% who reported having supportive classmates (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). Girls more frequently stated that parents understood problems and parents concerned free time than did boys (36.2% vs. 34.3% and 41.6% vs. 38.2%, respectively) (Table 2; Supplementary Tables S3, S4), and girls reported having slightly more supportive classmates compared with boys (41.4% vs. 37.6%). Low socioeconomic status more frequently stated low parental and peer support (Supplementary Tables S5, S6). The adolescents from the Western Pacific Region exhibited the lowest individual parental support (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2), and adolescents from the Africa Region reported the lowest prevalence in possessing close friendships and supportive classmates. According to the World Bank country-income classification, adolescents from low-income countries manifested the highest prevalence of individual parental support, while they showed the highest prevalence of having no close friendships (Table 2). At the country level, the overall prevalence of parents checking homework was highest in the United Republic of Tanzania (56.9%) and lowest in Malaysia (14.2%). The highest overall prevalence of parents understanding students problems and concerned students free time was in Curaçao (53.4% and 65.3%), with the lowest in Timor-Leste (11.5%) and Tuvalu (18.3%). The overall prevalence of parents respected for privacy was highest in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (91.6%), and lowest in the Solomon Islands (40.5%). The adolescents from Kiribati reported the highest prevalence of having one or more close friendships (97.7%), while Suriname exhibited the lowest (82.8%). The adolescents from Lebanon reported the highest prevalence of having supportive classmates (70.1%), while this index was lowest in Saint Kitts and Nevis (14.8%) (Supplementary Table S2; Figure 1).

TABLE 2. The prevalence of individual parental and peer support among young in-school adolescents by region, country income level, and gender groups (Low-income and middle-income countries, 2009–2015).

FIGURE 1. Individual parental and peer support in adolescents across country (Low-income and middle-income countries, 2009–2015). (A): Parents checked homework; (B): Parents understood problems; (C): Parents concerned free time; (D): Parents respected for privacy; (E): Having close friendships; (F): Having supportive classmates.

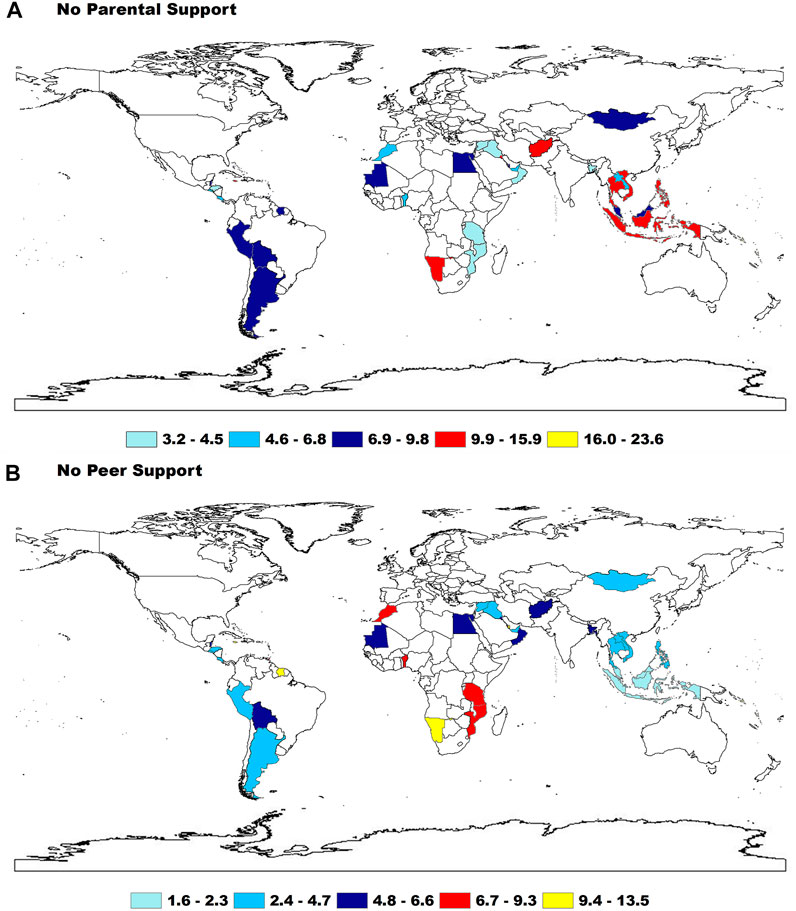

The overall prevalence of having no parental supportive was 8.8%, with the lowest in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (6.4%) and the highest in the Western Pacific Region (12.5%); with respect to country, it was lowest in Iraq (3.2%) and highest in Vanuatu (23.6%). The prevalence of having all four categories of parental support was 9.7%, with the lowest in Western Pacific Region (5.3%) and the highest in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (14.0%); with respect to country, the lowest was in Vanuatu (1.3%) and the highest in El Salvador (24.9%). The prevalence of having no peer support was 5.3% overall, with the lowest in the South-East Asia Region (4.1%) and the highest in the Africa Region (8.2%): for countries, the lowest was in Kiribati (1.6%) and the highest was in Swaziland (13.5%). The prevalence of having two peer-support mechanisms was 38.4%, with the lowest in the Africa Region (29.0%) and the highest in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (49.9%): for countries, the lowest was in Barbados (17.2%) and the highest was in Lebanon (68.7%) (Figure 2; Supplementary Tables S7, S8).

FIGURE 2. The prevalence of having no any parental and peer support among adolescents by WHO regions (Low-income and middle-income countries, 2009–2015).

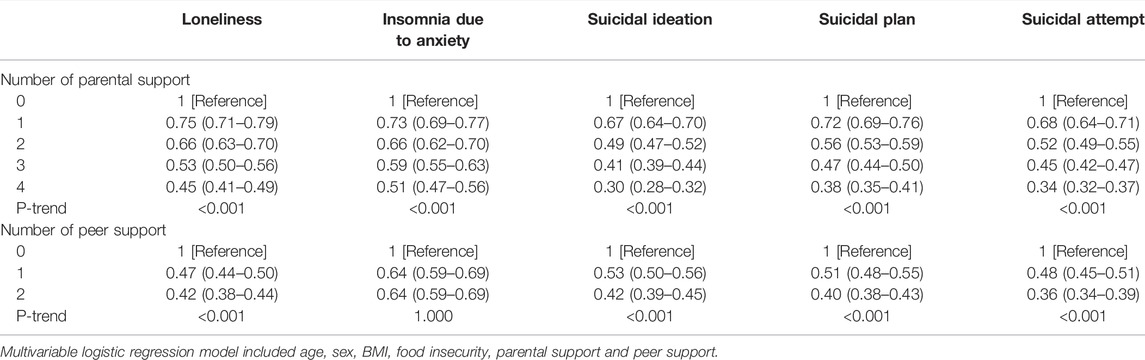

Overall, regarding the proxy of mental health factors, loneliness, insomnia due to anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicidal attempts were associated with parental support, and the associations were significantly enhanced by the increased number of parental support, as demonstrated by the significant ptrend value. Compared with adolescents who received no parental support, adolescents who received support in all four parental categories had the lowest ORs, with the ORs ranging from 0.30 (0.28–0.32) for suicidal ideation to 0.51 (0.47–0.56) for insomnia due to anxiety. Also, all mental health factors were associated with peer support. Additionally, the associations were significantly enhanced commensurate with increased numbers of parental support mechanisms, except for insomnia due to anxiety. The ORs of adolescents who had two peer support ranged from 0.36 (0.34–0.39) for suicidal attempts to 0.64 (0.59–0.69) for insomnia due to anxiety (Table 3). In addition, boys and girls had no difference in relationships between parental and peer support and mental health factors (Supplementary Tables S9, S10).

TABLE 3. The relationship between the number of parental and peer support and mental distress (Low-income and middle-income countries, 2009–2015).

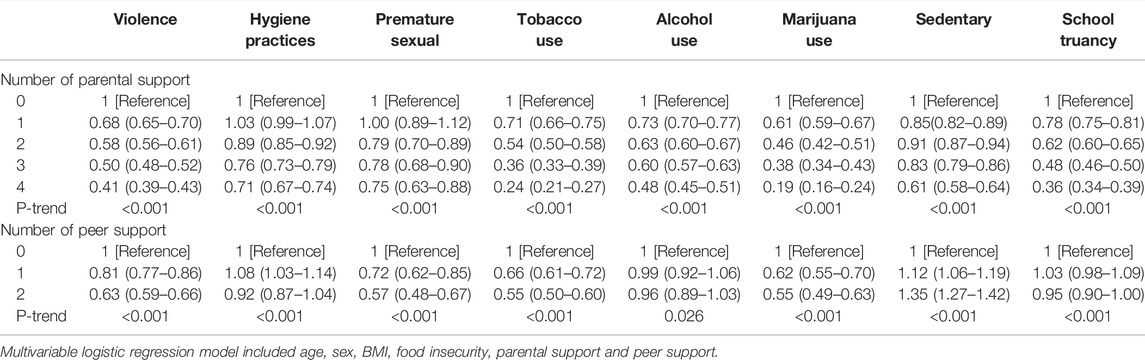

In terms of health risk behaviours—violence, hygienic practices, premature sexual activities, tobacco use, alcohol use, marijuana use, sedentary lifestyle, and school truancy were all associated with parental support, and the associations were significantly enhanced with increasing number of parental support. Adolescents who received all four parental support had the lowest ORs, with the ORs ranging from 0.19 (0.16–0.24) for marijuana use to 0.75 (0.63–0.88) for premature sexual activity. Parental support mechanisms were strongly associated with tobacco use, marijuana use, and school truancy. Moreover, five of eight health risk behaviours (violence, premature sexual activity, tobacco use, marijuana use, and sedentary lifestyle) were associated with peer support, and the association was significantly enhanced with an increased number of peer support. For sedentary lifestyles, the OR was 1.35 (1.27–1.42) in adolescents who received both peer-support mechanisms, while the ORs for the other four health risk behaviours were all approximately 0.60 (Table 4). Boys and girls also had no difference in relationships between parental and peer support and health risk behaviours (Supplementary Tables S9, S10).

TABLE 4. The relationship between the number of parental and peer support and health risk behaviours (Low-income and middle-income countries, 2009–2015).

Discussion

From this multi-country study based on nationally representative school-attending adolescents, only 40% of adolescents reported that parents checked homework, parents understood problems, and parents concerned free time—and that they had supportive classmates, while nearly 7 of 10 adolescents reported having parents who respected their privacy, and 9 of 10 adolescents reported having close friendships. Overall, the prevalences of having no parental support vs. having all four categories of parental support were 8.8% and 9.7%, respectively. The prevalence figures for having no vs. both peer-support mechanisms were 5.3% and 38.4%, respectively. Parental support was strongly associated with a lower odds of manifesting mental health factors and health risk behaviours independent of peer support, and adolescents demonstrating higher numbers of individual parental support exhibited stronger associations. Peer support was also strongly associated with mental health factors and major health risk behaviours independent of peer support, and the association was significantly enhanced commensurate with increasing numbers of individual peer support.

With this global study, we reported the prevalence of individual and combined parental and peer support carry substantial variations across countries and regions. At the regional level, adolescents from the Western Pacific Region and South-East Asia Region had the lowest parental support, and the Africa Region reported the lowest peer support. Parenting styles played the pivotal factor in the well-being of the adolescents [16–18]. We assumed that the variations in parenting styles may in part be due to the large differences across diverse economic, cultural, and religious beliefs globally [17]. In fact, parental involvement and support were vital behaviours reflecting parenting style and were usually related to the local socio-political system [18, 19]. In general, the parents who belonged to socially conservative or undemocratic countries were inclined to show more controlling parenting patterns than those in democratic and liberal political systems [18]. In addition, in most Southeast Asian countries, adolescents were used to being asked to respect their elders from childhood on due to Confucian ethics [19], and this relationship might be one reason for the lower parental support. Educational level and socioeconomic status of the parents might also be related to parental support: a family with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status would usually be more inclined to communicate openly with their children and to help their children understand the effects of behaviours and improve their self-efficacy [20]. In addition, the lowest peer support in the Africa Region might be due to poverty, political instability, and social unrest [21].

Mental health factors were all shown to clearly align with parental and peer support, with the associations being independent, and in our study, suicidal behaviours exhibited the strongest association. Previous investigators also described individual parental and peer-support associations with mental health problems (e.g., loneliness, insomnia due to anxiety, suicidal behaviours) in LMIC adolescents [9, 10]. In addition, the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study in the United States showed that adolescents aged 9–10 years with lower parental monitoring were more likely to manifest suicidal ideation and to attempt suicide [22]. The French iShare cohort also revealed that those participants who lacked perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence were more likely to exhibit occasional or frequent suicidal thoughts [23]. Adolescence is a vital period of human development due to the physical and psychological changes that take place and the accompanying establishment of self-identity, and, simultaneously, it is also a vulnerable period because of the need to deal with new interpersonal relationships independently [1]. Parental support mechanisms constitute the primary component of positive parent-adolescent relationships, and can confer resilience in combating suicidal behaviours by attenuating the impacts of the risk factors—such as peer victimization and bullying, and feelings of depression, loneliness, and hopelessness [24]. The perception of being cared for, having one’s privacy respected, and parental involvement in the education and lives of adolescents are associated with less adolescent mental distress [19]. Notably, parental support to adolescents can help them manage stress better and keep a healthy physical and mental status [9]. Also, peer support demonstrates a strong independent association with mental disorders by offering positive effects such as increased self-esteem [25], increased resilience [26], increased competence in solving problems, and improved physical and mental health. In our study, mental health factors were all associated with an increase in the number of parental and peer support mechanisms; i.e., those adolescents with a greater number of parental and peer support were less likely to manifest mental health concerns. The findings of our study may therefore present important public health implications in lowering the increasing incidence of mental distress in adolescents. It is vital for parents to realize the importance of parental and peer support to adolescent mental health, to encourage parents to pay more attention to care surrounding parent-adolescent relationships, and to encourage their children to cultivate more friendships.

Common health risk behaviours all showed a clear gradient that aligned with the increasing number of parental support, especially in the use of tobacco and marijuana. Substance use in adolescents exerts great harm on adolescent physical and mental health and also increases the risk for many diseases, such as respiratory illness and digestive system disease. Parents thus play a vital role in the development of health risk behaviours in adolescents. Our results corroborate previous research that concluded that parental monitoring exerts an effective positive influence on smoking intentions and willingness [27]. The observations from the Three Diverse Island Nations also show that lower rates of parental monitoring were significantly associated with more adolescent tobacco use [28]. Therefore, it is important for governments and parents to raise awareness on the effects of increasing parental support so as to decrease adolescent substance use and other health risk behaviours. In our study, we also noted a lack of any significant association between peer support and hygienic practices, alcohol use, or school truancy. Hygienic health practices are related to parental example and instruction, as adolescents principally imitate the behaviour of their parents [29]. Interestingly, those adolescents with a greater number of peer support exhibited risk factors for sedentary lifestyle. Indeed, sedentation is now very popular among adolescents from LMICs [30]. Adolescents spend more time watching TV and playing computer games, which entail long periods of sitting, and they are more likely to conduct these activities with their close friends [30]. Therefore, adolescents with more peer support exhibit more sedentary behaviour. In fact, parental and peer support were highly effective in diminishing health risk behaviours of adolescents, suggesting that parents pay more attention to parent-adolescent relationships.

There were several limitations to the study. First, the data in the GSHS was from school-attending, self-reported information, and recall bias can be problematic. In addition, the study’s validity might also be affected by the children’s ability to understand the questions. Second, due to the loss of some important question variables and high levels of heterogeneity across countries, the possibility of biases in overall prevalence estimates was inevitable. Third, this is a cross-sectional study, and the associations between parental and peer support and mental health factors and health risk behaviours should be interpreted with caution with respect to feasible reverse causation. Finally, in the multivariate logistic regression model, we only included age, sex, BMI, food insecurity, parental support, and peer support—with other confounding factors potentially lost in some countries.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in our study we demonstrated that there were important differences in the prevalence estimates of individual and combined parental and peer support across countries, regions, and country-income classifications. We have also shown that greater parental and peer support for adolescents was associated with mental health factors and components of the health risk behaviours, and the associations increased with increased parental and peer support. We therefore recommend that policy makers and parents adapt to the importance of parental and peer support to adolescent health, and create and promulgate global and national policies and take related actions to improve both parent-adolescent and peer relationships. Parents and teachers should participate in psychological education programs to aware the important of parental and peer support for reducing mental health problems and increaing the health behaviors, and them should promote a healthy home and school environment for adolescents together.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study will be availabled on https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/GSHS and http://www.cdc.gov/gshs.

Author Contributions

GB and LL conceived and designed the study. GX and PS compiled and prepared the study data for analysis. GX analysed the data. LL and YW wrote the first draft. GB and DZ reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to writing and review of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for submission for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Program of Social Development of Ningbo Science and Technology Bureau (2017C510012), Ningbo medical and health brand discipline (PPXK2018-08) and Ningbo medical & health leading academic discipline project (2022-F28).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control for making Global School-based Student Health Surveys (GSHS) data accessible for analysis, and the country survey participants and participating researchers involved in conducting GSHS.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604648/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sawyer, SM, Afifi, RA, Bearinger, LH, Blakemore, SJ, Dick, B, Ezeh, AC, et al. Adolescence: a Foundation for Future Health. Lancet (2012) 379(9826):1630–40. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

2. Jenssen, BP, Walley, SC, and Section On Tobacco, C. E-cigarettes and Similar Devices. Pediatrics (2019) 143(2):e20183652. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3652

4. Kieling, C, Baker-Henningham, H, Belfer, M, Conti, G, Ertem, I, Omigbodun, O, et al. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Worldwide: Evidence for Action. Lancet (2011) 378(9801):1515–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

5. Christiansen, L, Beck, MM, Bilenberg, N, Wienecke, J, Astrup, A, and Lundbye-Jensen, J. Effects of Exercise on Cognitive Performance in Children and Adolescents with ADHD: Potential Mechanisms and Evidence-Based Recommendations. J Clin Med (2019) 8(6):E841. doi:10.3390/jcm8060841

6. Biswas, T, Scott, JG, Munir, K, Renzaho, AMN, Rawal, LB, Baxter, J, et al. Global Variation in the Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation, Anxiety and Their Correlates Among Adolescents: A Population Based Study of 82 Countries. EClinicalMedicine (2020) 24:100395. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100395

7. Beaglehole, R, Bonita, R, Horton, R, Adams, C, Alleyne, G, Asaria, P, et al. Priority Actions for the Non-communicable Disease Crisis. Lancet (2011) 377(9775):1438–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0

8. Gore, FM, Bloem, PJ, Patton, GC, Ferguson, J, Joseph, V, Coffey, C, et al. Global burden of Disease in Young People Aged 10-24 Years: a Systematic Analysis. Lancet (2011) 377(9783):2093–102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6

9. Tian, S, Zhang, TY, Miao, YM, and Pan, CW. Psychological Distress and Parental Involve- Ment Among Adolescents in 67 Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Population-Based Study. J Affect Disord (2021) 282:1101–9. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.010

10. Kushal, SA, Amin, YM, Reza, S, and Shawon, MSR. Parent-adolescent Relationships and Their Associations with Adolescent Suicidal Behaviours: Secondary Analysis of Data from 52 Countries Using the Global School-Based Health Survey. EClinicalMedicine (2021) 31:100691. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100691

11. Khan, SR, Uddin, R, Mandic, S, and Khan, A. Parental and Peer Support Are Associated with Physical Activity in Adolescents: Evidence from 74 Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(12):E4435. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124435

12. Viner, RM, Haines, MM, Head, JA, Bhui, K, Taylor, S, Stansfeld, SA, et al. Variations in Associations of Health Risk Behaviors Among Ethnic Minority Early Adolescents. J Adolesc Health (2006) 38(1):55. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.017

13. Ma, C, Bovet, P, Yang, L, Zhao, M, Liang, Y, and Xi, B. Alcohol Use Among Young Adolescents in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: a Population-Based Study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health (2018) 2(6):415–29. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30112-3

14. Park, JS, Choi, YJ, Suh, DI, Jung, S, Kim, YH, Lee, SY, et al. Profiles and Characteristics of Bronchial Responsiveness in General 7-Year-Old Children. Pediatr Pulmonol (2019) 54(6):713–20. doi:10.1002/ppul.24310

15. Ashdown-Franks, G, Vancampfort, D, Firth, J, Veronese, N, Jackson, SE, Smith, L, et al. Leisure-Time Sedentary Behavior and Obesity Among 116, 762 Adolescents Aged 12-15 Years from 41 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Obesity (2019) 27(5):830–6. doi:10.1002/oby.22424

16. Uji, M, Sakamoto, A, Adachi, K, and Kitamura, T. The Impact of Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Styles on Children’s Later Mental Health in Japan: Focusing on Parent and Child Gender. J Child Fam Stud (2014) 23(2):293–302. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9740-3

17. Khodabakhsh, MR, Kiani, F, and Ahmadbookani, S. Psychological Well-Being and Parenting Styles as Predictors of Mental Health Among Students: Implication for Health Promotion. Int J Pediatr Otorhi (2014) 2:39–46. doi:10.22038/ijp.2014.3003

18. Dwairy, M, Achoui, M, Abouserie, R, Farah, A, Sakhleh, A, Fayad, M, et al. Parenting Styles in Arab Societies: A First Cross-Regional Research Study. J Cross Cult Psychol (2006) 37:230–47. doi:10.1177/0022022106286922

19. Nguyen, HTL, Nakamura, K, Seino, K, and Al-Sobaihi, S. Impact of Parent-Adolescent Bonding on School Bullying and Mental Health in Vietnamese Cultural Setting: Evidence from the Global School-Based Health Survey. BMC Psychol (2019) 7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40359-019-0294-z

20. Assadi, S, Zokaei, N, Kaviani, H, Mohammadi, M-R, Ghaeli, P, Gohari, M, et al. Effect of Sociocultural Context and Parenting Style on Scholastic Achievement Among Iranian Adolescents. Soc Dev (2007) 16:169–80. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00377.x

21. Cluver, L, Orkin, M, Boyes, ME, and Sherr, L. Child and Adolescent Suicide Attempts, Suicidal Behavior, and Adverse Childhood Experiences in South Africa: A Prospective Study. J Adolesc Health (2015) 57(1):52–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.001

22. DeVille, DC, Whalen, D, Breslin, FJ, Morris, AS, Khalsa, SS, Paulus, MP, et al. Prevalence and Family-Related Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, and Self-Injury in Children Aged 9 to 10 Years. JAMA Netw Open (2020) 3(2):e1920956. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956

23. Macalli, M, Tournier, M, Galera, C, Montagni, I, Soumare, A, Cote, SM, et al. Perceived Parental Support in Childhood and Adolescence and Suicidal Ideation in Young Adults: a Cross-Sectional Analysis of the I-Share Study. BMC Psychiatry (2018) 18(1):373. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1957-7

24. Gallagher, ML, and Miller, AB. Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior in Children and Adolescents: An Ecological Model of Resilience. Adolesc Res Rev (2018) 3(2):123–54. doi:10.1007/s40894-017-0066-z

25. Kleiman, EM, and Riskind, JH. Utilized Social Support and Self-Esteem Mediate the Relationship between Perceived Social Support and Suicide Ideation. A Test of a Multiple Mediator Model. Crisis (2013) 34(1):42–9. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000159

26. Herrenkohl, T. Book Review: The Context of Youth Violence: Resilience, Risk, and Protection. J Interpers Violence (2002) 17:228–30. doi:10.1177/0886260502017002008

27. Mahabee-Gittens, EM, Xiao, Y, Gordon, JS, and Khoury, JC. The Role of Family Influences on Adolescent Smoking in Different Racial/ethnic Groups. Nicotine Tob Res (2012) 14(3):264–73. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr192

28. Shaikh, MA, Zare, Z, Ng, KW, Celedonia, KL, and Lowery Wilson, M. Tobacco Use and Parental Monitoring-Observations from Three Diverse Island Nations-Cook Islands, Curacao, and East Timor. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 17(20):E7360. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207360

29. Smith, L, Butler, L, Tully, M, Jacob, L, Barnett, Y, López-Sánchez, G, et al. Hand-Washing Practices Among Adolescents Aged 12-15 Years from 80 Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2020) 18:E138. doi:10.3390/ijerph18010138

Keywords: adolescents, mental distress, parental support, peer support, unhealthy behaviours

Citation: Li L, Xu G, Zhou D, Song P, Wang Y and Bian G (2022) Prevalences of Parental and Peer Support and Their Independent Associations With Mental Distress and Unhealthy Behaviours in 53 Countries. Int J Public Health 67:1604648. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604648

Received: 29 November 2021; Accepted: 27 September 2022;

Published: 10 October 2022.

Edited by:

Tibor Baska, Comenius University, SlovakiaReviewed by:

Joko Adianto, University of Indonesia, IndonesiaBarbara Settles, University of Delaware, United States

Copyright © 2022 Li, Xu, Zhou, Song, Wang and Bian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yucheng Wang, NDYyNjA1OTA1QHFxLmNvbQ==; Guolin Bian, YmlhbmdsMTIzQDE2My5jb20=

Lian Li

Lian Li Guodong Xu2

Guodong Xu2 Guolin Bian

Guolin Bian