- 1Accident Research Centre, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

- 2Department of Health, State Government of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 3Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, Monash University, Frankston, VIC, Australia

- 4Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC, Australia

- 5School of Primary and Allied Health Care, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, Monash University, Frankston, VIC, Australia

- 6National Centre for Healthy Ageing, Faculty of Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, Monash University, Frankston, VIC, Australia

Objectives: Effective public policy to prevent falls among independent community-dwelling older adults is needed to address this global public health issue. This paper aimed to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement of future policies to increase their likelihood of success.

Methods: A systematic scoping review was conducted to identify policies published between 2005–2020. Policy quality was assessed using a novel framework and content criteria adapted from the World Health Organization’s guideline for Developing policies to prevent injuries and violence and the New Zealand Government’s Policy Quality Framework.

Results: A total of 107 articles were identified from 14 countries. Content evaluation of 25 policies revealed that only 54% of policies met the WHO criteria, and only 59% of policies met the NZ criteria. Areas for improvement included quantified objectives, prioritised interventions, budget, ministerial approval, and monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusion: The findings suggest deficiencies in a substantial number of policies may contribute to a disconnect between policy intent and implementation. A clear and evidence-based model falls prevention policy is warranted to enhance future government efforts to reduce the global burden of falls.

Introduction

Falls among older adults living independently in the community are associated with thousands of fatalities and injuries around the world, and are recognised as a persistent and growing public health issue by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1, 2] and the Global Burden of Disease Study [3]. Falls are also relevant to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [4] and there are opportunities to embed and align falls prevention efforts within broader development agendas [5]. The vast majority of older adults live independently in the community and the falls-related injuries they experience are tremendously costly to the older person, their families and communities, as well as to social, health and aged care systems worldwide [1, 3, 6–12]. These costs are projected to increase in the coming decades as populations of older adults above the age of 65 years are expected to more than double from 700 million to over 1.5 billion by 2050 [13]. Falls prevention for community-dwelling older people (FPC) is achieved through implementation of evidence-based interventions and strategies [2, 14–19]. For the most part, interventions are underpinned by government public health policy.

Effective government policy is needed to achieve FPC objectives, to inform political decision making for successful implementation of interventions, and to support a systems-approach to falls prevention [1, 20–22]. The WHO highlighted promising public policy approaches in Canada, USA and Europe [1] to stimulate governments to develop effective public policies for falls prevention, especially in countries with ageing populations. Despite this innovation, its effect on the development of effective policies is unclear. Notwithstanding, there is some suggestion that falls prevention policy has not received sufficient political priority to impact on population health [23, 24], but it is unclear why. Indeed, the global burden of falls, which is now greater than transport injury, poisoning, drowning and burns combined, gave the impetus for the WHO’s latest release of the Step Safely Technical Package and its renewed call that “Now is the time to push the prevention and management of falls higher up the planning, policy, research and practice agenda…”[2] (p.vii).

Policy formulation comprises a process of discrete steps involving problem identification, agenda setting, adoption, implementation and evaluation [25, 26]. This process, often referred to as the “policy cycle” is rarely linear or sequential due to complexities of politics, policy and administration [20, 27–29]. Evidence from public health policy analysis can improve the progression of policy through the policy cycle and potentially increase policy impact on population health [30–37].

While the quality of public policies ultimately lies in their successful implementation [38–40], quality can also be inferred from the content of published policy documents [23, 41–44]. The WHO guideline for Developing policies to prevent injuries and violence [45] and several more recent frameworks provide guidance for policy content evaluation according to systematic criteria [41, 46–50], however FPC public policies appear not to have been reviewed in this way to date.

Given the importance of robust policy analysis in facilitating effective FPC, this paper aims to map and describe international public policy related to FPC and to identify gaps, strengths, weaknesses and opportunities for improvement of future FPC policy to increase the likelihood of their success.

Methods

A two-phased approach was adopted to address the objectives of the study, described below.

Phase 1: Exploration and Mapping of Policy Documents

This phase used a systematic scoping review methodology [51–54] to address the research question “What is the extent and nature of literature relating to international government policy for falls prevention among older adults living independently in the community from 2005 to 2020?” A protocol was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Scoping Review Guidelines and the PRISMA-SCR Checklist [54] to identify, select and chart the data.

Identification of Policy Documents

Publicly available literature on policies related to FPC published between 2005–2020 was identified in a primary search using two sources including 1) bibliographic databases and grey literature repositories, and 2) a desktop search of the websites of the World Health Organization and relevant government and health ministries (of Australia, New Zealand, UK, Europe, Canada and USA, and Asia) and Google. Bibliographic databases included MEDLINE (Ovid Interface); PUBMED (Ovid Interface); EMBASE (Ovid Interface); Cochrane Library (Ovid Interface); Global Health (Ovid Interface); SCOPUS; Web of Science; CINAHL; ProQuest (including ProQuest Policy File Index and PAIS Index); Open Access Theses and Dissertations (OATD). Grey literature repositories included Research Professional, ResearchGate, OpenGrey, GreyLit, InformIT, and SafetyLit platforms. A secondary search was conducted using a snowball method [55–57] of checking the narratives and references of articles found in the primary search and contacting key authors and experts in falls prevention for any other documents.

This search adopted a broad and inclusive definition of “public policy” that included policies authored or enacted by systems of government for the population they serve [25, 27, 58]. Public policy can include political agendas or statements of strategic plans or implementation and action plans, and “policy instruments” of laws and regulations, agreements, standards or guidelines, funded programs or services, public advocacy or education campaigns, or government networks or collaborations [27, 33]. Based on the WHO guideline [45], “public policy related to FPC” was deemed to be a publicly available document outlining the vision, goals, objectives, actions and mechanisms for government to prevent or reduce falls and fall-related injuries, deaths or their health consequences, among older adults living independently in the community setting.

An inclusive syntax of search terms was used (Supplementary Table S1 showing key concepts and keywords), with Boolean operators and truncation (Supplementary Table S2). The index year of 2005 was chosen based on the Australian 2005 National Falls Prevention Plan [59]. All study designs were included, and the search was limited to literature with English-language abstracts due to study time and resource limitations.

Selection of Policy Documents

Published and grey literature was selected using inclusion and exclusion eligibility criteria (Supplementary Table S3) and the COVIDENCE literature screening online tool (web-based systematic review management system). Two independent reviewers (AN and KT) systematically screened the identified literature for relevance, first by title and abstract and then by full-text. Literature identified with an English-language abstract that had non-English full-text were translated using Google Translator. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) scores were calculated. To increase consistency and inter-rater reliability between the reviewers’ screening of the literature, the first 100 articles were independently screened by two reviewers (AN and KT) and conflicts were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third reviewer (JO).

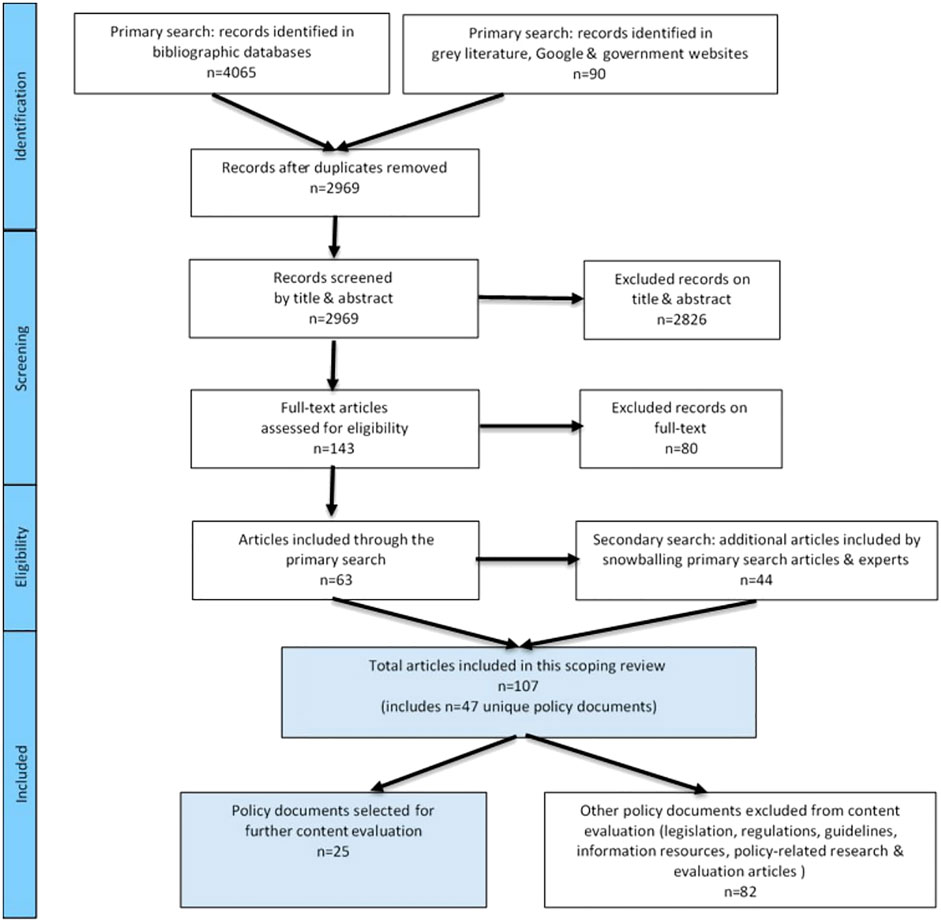

4,155 articles were identified (4,065 sourced from bibliographic databases and 90 from grey literature) (Figure 1), Following the screening and inclusion/exclusion process, the primary search for literature yielded 63 articles, and the secondary search found a further 44 articles, hence a total of 107 articles were included in the review, 47 of which were unique public policy documents.

FIGURE 1. Flow diagram showing selection of public policies for this scoping review and content evaluation (Melbourne, Australia, 2020–21).

Data Extraction and Assessment

Relevant data was extracted from the included 107 articles and imported into a Microsoft Excel (2019) spreadsheet. The chart was iteratively refined as data were extracted, and as secondary search articles were found. Data of interest included broad characteristics of author, year of publication, type of publication, search source, name of policy, country of origin, jurisdiction of policy, type of policy document, policy framing, and evidence of evaluation. These characteristics were collated and descriptive statistics applied.

Phase 2: Content Evaluation of Selected Policy Documents

In addition to identifying and mapping policy documents, a content evaluation was undertaken to assess the quality of policies and address the research question “What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing FPC policies?”

Data Source

From the 107 identified articles, a sub-set of FPC public policies, strategic plans, action plans and position statements (n = 25) were selected for further content evaluation using our novel framework. Other documents such as legislation and regulations, guidelines and information resources, policy-research and evaluation articles, and those not written in English were excluded. For the national and state policies that had multiple iterations, only the most recent published policy version was included.

Data Extraction

There is no one internationally agreed method for policy content analysis [23, 41–44]. Hence, to assess the quality of FPC policies identified in this scoping review, a novel content evaluation framework was constructed that included 20 policy criteria adapted from two internationally recommended guidelines developed by the WHO for policy development in injury and violence prevention [45] and the Government of New Zealand (NZ) Policy Quality Framework [50] and checklist [60] that were designed to increase the quality of policy development across all government sectors.

Microsoft Excel (2019) worksheets were developed to allow two reviewers (AN and KT) to independently read the selected 25 policy documents and record categorical scores (YES = 1, NO = 0, UNCLEAR = 0.5) for the presence or absence of text in the documents that met each of the pre-defined criteria. IRR scores were generated. Discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer (JO).

Data Analysis

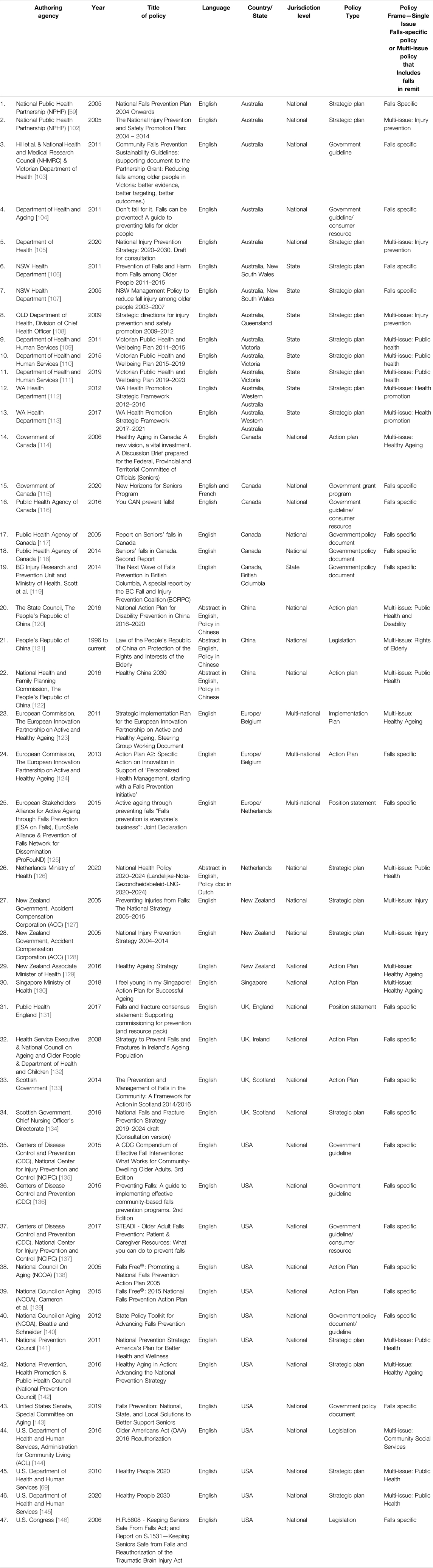

Quantitative and qualitative analyses of policy content were undertaken. The proportion of policies that met each of the criteria were summed and expressed as percentages. Percentage scores of the two reviewers were averaged and aggregate percentages for the 20 criteria for the evaluated 25 policies were generated. In addition, reviewer observations were thematically assessed. Excel radar charts were generated to illustrate the policy relationships with the criteria.

Results

Overview of Policy Documents

A total of 107 articles were selected for inclusion in the review. Assessment of their broad characteristics revealed that the majority of articles originated from the USA (n = 47), followed by Australia (n = 26), and Canada (n = 14). Additional articles were identified from the UK (n = 4), New Zealand (n = 3), China (n = 3), Singapore (n = 1), Switzerland (n = 1), Netherlands (n = 1), European Region (n = 5), and included two global-oriented WHO reports. The majority of articles (72%) were descriptive reviews and research commentaries (20 from bibliographic databases, 57 from grey literature) and the remaining articles (28%) related to policy evaluations (14 from bibliographic databases and 16 from grey literature).

Further assessment of these articles identified 47 unique government policies relating to FPC, i.e., some policies were described by multiple articles. An operational definition of “policy” was provided in only four articles [21, 61–64]. These policy definitions were broadly consistent with the policy definition used in this scoping review. Only eight articles specified the guiding theoretical or conceptual framework on which the policies were based, and these included the public health approach [65–67], social and environmental determinants of health [68, 69], prevention continuum [62], quality improvement [70] and a legal framework [71].

Table 1 outlines the key characteristics of 47 policies included in this review. These policy documents represented Australia (n = 13), Canada (n = 6), China (n = 3), European region (n = 3), Netherlands (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 3), Singapore (n = 1), UK (England, Ireland, Scotland) (n = 4), and USA (n = 13). Of these policies, the majority (75%) were national, 19% were from state government jurisdictions, and 6% were multi-national in the European region. Policy authors included national or state government health ministries or agencies, government-funded national advisory organisations (e.g., National Council of Aging (NCOA) in the USA) or multi-agency consortia (e.g., British Columbia Fall and Injury Prevention Coalition (BCFIPC) in Canada and the Prevention of Falls Network for Dissemination (ProFouND) and EuroSafe in Europe).

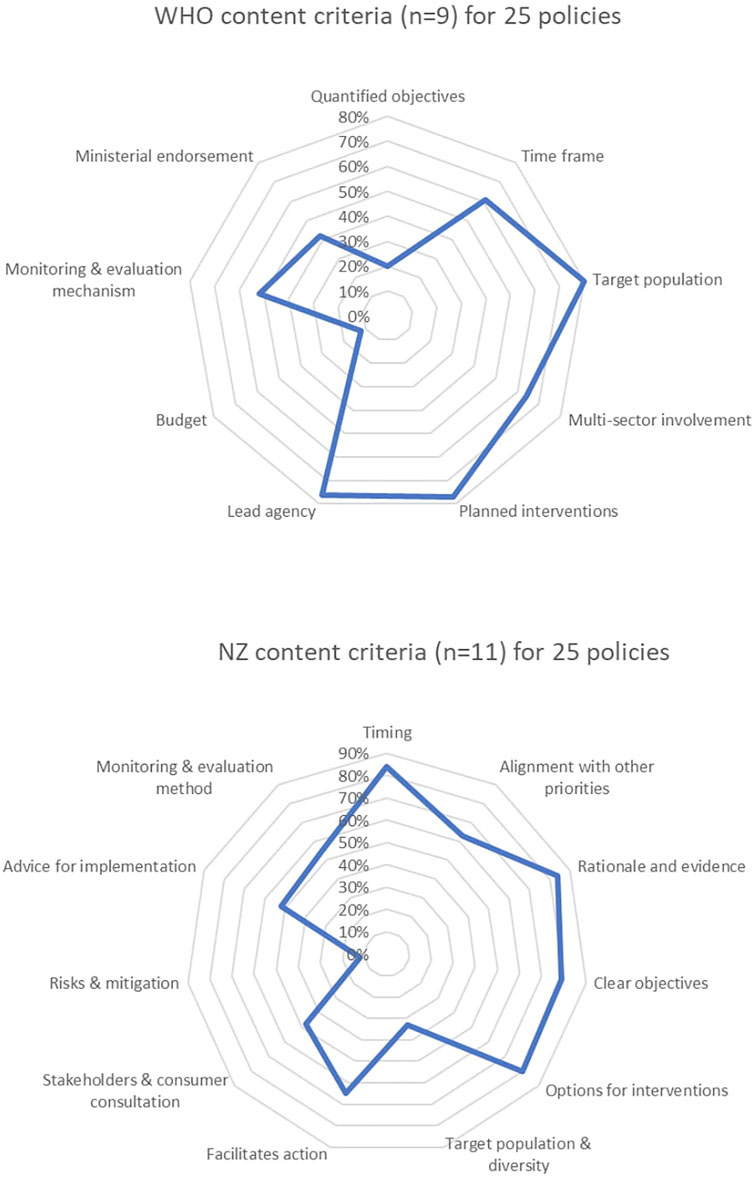

TABLE 1. Details of 47 policy documents identified in the scoping review and their key characteristics (sorted alphabetically by Country/State), (Melbourne, Australia, 2020–21).

The policies included strategic plans and action/implementation plans, position statements, and other policy documents such as legislation, guidelines and information resources for consumers, practitioners and organisations in the community and government grant funding program. Twenty four of the policies (51%) were single-issue policies specifically for falls prevention, whereas the other 23 policies (49%) were multi-issue policies that included falls prevention in their remit. All of the multi-issue policies were from the health sector, and related to injury prevention, healthy ageing, health promotion or public health, and none were from the aged care sector.

Content Evaluation of Selected Policy Documents

The results of our content evaluation of the selected 25 FPC policy documents are presented in Table 2. Overall proportions of the policy documents that met the 20 criteria are expressed as aggregate percentages of all policies. In addition, reviewer observations for each criteria are included. A traffic light system was applied to benchmark and highlight strengths and weaknesses of the policies. Green areas indicate well met criteria, i.e., 75 percent or more policies included the criteria (such as planned interventions, lead agency, timing and rationale). Yellow areas show the criteria that were included in 50–75 percent of the policies, and included stakeholder diversity and consumer involvement, and monitoring and evaluation. Red areas represent the criteria most deficient in the policies, namely quantified objectives, ministerial/ministry approval, allocated budget and risk and mitigation.

TABLE 2. Policy content evaluation framework showing aggregate results for selected 25 policy documents, (Melbourne, Australia, 2020–21).

The findings of the content evaluation for both the WHO and New Zealand criteria are further visually illustrated using Excel radar charts (Figure 2). Overall, only 54% of policies met the WHO recommended 9 criteria, and only 59% of policies met the NZ recommended 11 criteria.

FIGURE 2. Radar charts showing percentage of public policies that met the 20 criteria of the policy content evaluation framework (Melbourne, Australia, 2020–21).

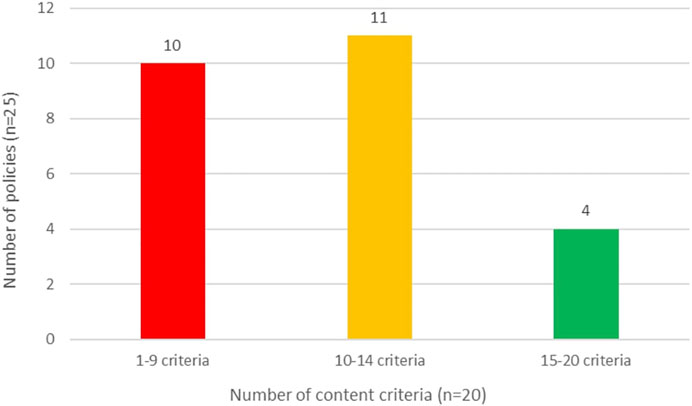

Figure 3 provides a high-level summary of the FPC policy content evaluation results. Only 4 (16%) policies met at least 75% of the criteria, while 10 (40%) met less than 50% of the criteria. It is important to note that no single policy was found to be a model policy meeting 100% of the criteria.

FIGURE 3. Summary of 25 public policies meeting 20 criteria in the policy content evaluation framework (Melbourne, Australia, 2020–21).

Discussion

We have identified numerous policies from around the world indicating considerable effort by multiple governments to tackle falls-related morbidity and mortality. Our review provides an international policy map that has previously only been commented on for individual countries at one time [62, 63, 67, 71–73]. The documents provide a rich source of information about policy approaches, jurisdictions, stakeholders, processes and intended implementation actions that can assist policy makers in future policy development [41]. However, we identified that no single policy addressed all of the recommended policy criteria as recommended in either the WHO or NZ guidelines. There were inconsistencies in structure, duration, policy framing and other characteristics which suggest countries may be at different levels of maturity in addressing falls and falls-related injury. The heterogenous nature of the FPC policies identified also suggests individual country context factors may play a strong role in how they are designed [20]. For example, countries with national policies and corresponding sub-national/state policies (USA, Canada and Australia) may reflect their federated systems of government. This implies that administrative and non-mandatory FPC policies identified in this review have shared responsibility by multiple layers of government, making them potentially difficult to implement [38, 39].

Falls prevention in the community setting appears to have been a priority in many countries at some point, however, whether it is still a priority is unclear. We found several FPC-related policy iterations in Canada, USA, Scotland and Australia’s state of New South Wales, which may suggest these jurisdictions have had continued political attention on the issue of falls. However, some policies were expired (Australia, Ireland), which may imply that FPC may have lost status as a priority public health issue. Our evidence does not provide enough information to know the trajectory of published policies, so it is difficult to ascertain if the expired policies have ceased or simply lapsed, or been modified to take a different approach. We suggest the latter may be more likely as we found some evidence of embedding falls prevention in more recent multi-issue public health policies (NZ, Singapore, Switzerland, USA). USA and New Zealand had concurrent single-issue falls policies and embedded policies. Stand-alone falls prevention policies are by nature focused and more “niche” public health policies, and could be vulnerable to changing agendas of elected governments [27], hence embedding into other policy priorities allows for strategic alignment with more mass-appealing issues [74]. Embedded FPC policies may have better prospects of attracting political attention [75, 76] and ideally more resources for implementation. Despite the presence of these policies, previous research notes that adequate political priority has not been given to falls prevention policies [22, 23, 77, 78]. We postulate that, if political priority is to be achieved, the quality of falls prevention policy formulation needs to be improved.

Some of the common deficiencies found in policy content suggest that FPC policies may be too broad in scope, lack important detail and therefore open to misinterpretation, confusion and delay in action [27, 79]. Specifically, while all of the policies aimed to prevent falls in their communities or reduce falls-related injury and their consequences, the majority lacked quantified objectives for falls-injury incidence reduction. While over three-quarters of policies stipulated target populations of “older people” (predominantly over the age of 60 or 65 years), only one-third adequately defined their size of this population or diversity of sub-groups most at risk of falls-related injury—these are important considerations for targeting and scaling of implementation interventions [80–85]. This is supported by Ma et al. [5] who have identified opportunities for falls prevention targets to be made explicit in the SDGs to address the global burden of falls.

Only half of falls policies reported inclusion of consumer consultation during development which may imply that older people as citizens and direct beneficiaries of the policies are not always front and centre of ministerial decisions and the preventable human cost of falls is not mitigated by ministers whom have power to enable system change [86, 87]. Similarly, although over three-quarters of policies articulated comprehensive intervention options, half lacked prioritisation and even fewer provided definitive timeframes, which are necessary for workable and decisive action [29, 81].

Only 42% of the policies articulated formal approval by a government minister or ministry, and only 3 policies (12%) identified risks and mitigations of potential positive or negative consequences of the policy. We highlight that attention to funding was shown by only 12% of policies specifying or implying a budget to finance the policy, limiting the allocation of resources [88]. FPC policies, which are typically siloed health sector policies, may also be missing opportunities for a systems approach and collaborative funding from equally relevant sectors (i.e., aged care, housing and transport) to raise the political priority of FPC [2, 5].

These lost opportunities may contribute to a disconnect between policy intent and implementation [24]. It is plausible that governments intentionally publish broad “high level” policies for FPC to allow some discretion to the multi-stakeholders who implement them [27] and to allow long lead times to demonstrate outcomes. However, evidence of successful implementation of other public health policies, such as road safety and suicide prevention [89–92], suggests that falls prevention policy would benefit from setting more specific objectives. This recommendation was also highlighted by prominent injury prevention researchers, in calls for national institutions to play a greater role in “precision prevention” to reduce preventable deaths and injuries, such as from falls [93].

Many policies appear to have been designed with little capacity to be evaluated. Only half of the policies we assessed met the content criteria of having a dedicated monitoring and evaluation mechanism to evaluate implementation and effectiveness in achieving objectives in place, and outcome measures were rarely clearly specified. This may suggest that some governments do not have well-developed falls surveillance information systems in place [94–96] and/or that reliable monitoring of falls among older people in the community setting is challenging [97, 98]. It may also suggest that some policies are designed without these accountability mechanisms being put in place even when data monitoring systems are available, making it impossible to evaluate the impact of the policy [99, 100].

Limitations

The strength of this scoping review is that it is the first study to identify and examine the content of a considerable number and variety of international policies governing FPC at national and state jurisdictional levels, hence it fills an important gap in public health policy addressing the health, safety and wellbeing of community-dwelling older people. Our retrospective content evaluation of FPC reveal how intertwined policy content is, and where there is scope to enhance the comprehensiveness of policy documents in ways that are likely to increase the impact of these policies. Future use of evidence-based policy development checklists and criteria is encouraged, particularly to strengthen policies during development and to review them when in evaluation stage.

A limitation of this scoping review is its reliance on published government policy documents in the English language, hence our findings may not be generalisable to all countries, particularly those low to middle income countries. Our search strategy made considerable effort to comprehensively and systematically identify relevant policy documents with at least an English-language abstract, and Google Translator was used for policies with non-English full text, such as policies for China and the Netherlands. Some governments may not have published their policies, or may have outsourced them to non-government organisations, so they may have been missed by the search strategy we employed. To the best of our knowledge, the identified policy documents from a large range of countries is the most comprehensive collection to date and will provide a good starting point for further research.

This review excluded government policy authored by local/provincial government jurisdictions and for falls prevention directed at non-community setting older people, i.e., those in primary/acute/hospital settings and residential aged care/nursing home settings, so it is possible that our quality assessment of this group of policies might reveal different results. The policies reviewed in this study were high-level national and state jurisdictional documents and due to the nature of their content may have lacked the details we were assessing, hence affecting the results. Although the content criteria were adapted from internationally recommended policy development guidelines they were limited and open to interpretation and our low-moderate inter-rater reliability (IRR) scores reflected the reviewers’ differing levels of knowledge and familiarity with the topics of falls prevention, public policy, as well as the guidelines. While we assessed whether recommended criteria were stated in the policy documents, it is also important to acknowledge that published policy documents might not reflect the totality of the policy process [40].

Finally, we note that although this review focused on good quality policy content, the quality of policy is ultimately determined by its effective implementation and impact [34, 41, 101]. This warrants further research to understand which of the FPC policies identified in this scoping review may have effectively led to delivery of the intended interventions for community-dwelling older people and ultimately led to a reduction in falls, fall-related injuries and other costs associated with falls.

Conclusion

This scoping review has shown, encouragingly, that governments around the world are actively pursuing the prevention of falls in community settings by developing a variety of national and state-level public policies. Benchmarking policy content using broad internationally recommended criteria for policy development revealed several content deficiencies in FPC policies which may contribute to a disconnect between policy intent and implementation. While application of these criteria may assist policy makers to improve future falls prevention policies, there is a need for a more focused, clear and evidence-based model policy for falls prevention among community-dwelling older people to enhance future government efforts.

Author Contributions

Policy scoping review concept and design, AN; Protocol development, AN; Protocol review, JO, TH, and LB approved on 11/09/2020; Literature search, AN; Literature screening and selection, AN, KT, and JO; Data charting, AN; Policy content evaluation framework design, AN; Policy content evaluation according to criteria, AN, KT, and JO; Analyses and interpretation, AN; Manuscript drafting, AN; Critical revision of the manuscript, JO, TH, LB, and BB.

Funding

This review was conducted as part of the lead author’s Doctoral study as part of the MUARC Injury Prevention Graduate Research Industry Partnership (IP-GRIP) Program, and is supported by a scholarship jointly funded by the Victorian Department of Health and Monash University.

Author Disclaimer

The findings and conclusion are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of MUARC or the views of the Victorian Department of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Milica Markovic for guidance and support, and to Penelope Presta and Dr Carlyn Muir for their valuable comments on the literature search and policy quality evaluation methods.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604604/full#supplementary-material

References

1.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age. Geneva: World Health Organization (2007).

2.World Health Organization (WHO). Step Safely: Strategies for Preventing and Managing Falls across the Life-Course. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

3. James, SL, Lucchesi, LR, Bisignano, C, Castle, CD, Dingels, ZV, Fox, JT, et al. The Global burden of Falls: Global, Regional and National Estimates of Morbidity and Mortality from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Inj Prev (2020) 26(Suppl. 1):i3–i11. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043286

4.United Nations (UN). Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals (2021). [Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

5. Ma, T, Peden, AE, Peden, M, Hyder, AA, Jagnoor, J, Duan, L, et al. Out of the Silos: Embedding Injury Prevention into the Sustainable Development Goals. Inj Prev (2020) 27(2):166–71. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2020-043850

6. Burns, ER, Stevens, JA, and Lee, R. The Direct Costs of Fatal and Non-fatal Falls Among Older Adults - United States. J Saf Res (2016) 58:99–103. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2016.05.001

7. Davis, JC, Robertson, MC, Ashe, MC, Liu-Ambrose, T, Khan, KM, and Marra, CA. International Comparison of Cost of Falls in Older Adults Living in the Community: a Systematic Review. Osteoporos Int (2010) 21(8):1295–306. doi:10.1007/s00198-009-1162-0

8. Moller, J, National Ageing Research Institute (NARI). Australian Department of Health and Ageing A, Substance Misuse and Injury Prevention Section, National Falls Prevention for Older People Initiative. Projected Costs of Fall Related Injury to Older Persons Due to Demographic Change in Australia. Report to the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing under the National Falls Prevention for Older People Initiative. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia (2003). Contract No.: ISBN 0 642 82313 8.

9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Centre for Clinical Practice. Falls: Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older People. NICE Clinical Guideline 161. London, UK: NICE (2013).

10. Pin, S, and Spini, D. Impact of Falling on Social Participation and Social Support Trajectories in a Middle-Aged and Elderly European Sample. SSM - Popul Health (2016) 2:382–9. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.004

11. van der Meulen, E, Zijlstra, GAR, Ambergen, T, and Kempen, GIJM. Effect of Fall-Related Concerns on Physical, Mental, and Social Function in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: a Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc (2014) 62(12):2333–8. doi:10.1111/jgs.13083

12. Zhang, Y, Zhang, L, Zhang, L, Zhang, X, Sun, J, Wang, D, et al. Fall Injuries and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults and the Mediating Effects of Social Participation - China, 2011-2018. CCDC Weekly (2021) 3(40):837–41. doi:10.46234/ccdcw2021.207

13.United Nations (UN). World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD (2019).

14. Andersen, M, Ma, T, Bhamuik, S, Nguyen, H, Lim, ML, Lukaszyk, C, et al. Synthesis of Evidence to Inform a Technical Package on Falls Prevention and Management. Newtown, NSW, Australia: The George Institute for Global Health (2020).

15. Gillespie, LD, Robertson, MC, Gillespie, WJ, Sherrington, C, Gates, S, Clemson, L, et al. Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2012) 2021:CD007146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3

16. Hopewell, S, Adedire, O, Copsey, BJ, Boniface, GJ, Sherrington, C, Clemson, L, et al. Multifactorial and Multiple Component Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2018) 7:CD012221. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012221

17. McClure, RJ, Turner, C, Peel, N, Spinks, A, Eakin, E, and Hughes, K. Population-based Interventions for the Prevention of Fall-Related Injuries in Older People. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2005) 2005:CD004441. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004441

18. Sherrington, C, Fairhall, NJ, Wallbank, GK, Tiedemann, A, Michaleff, ZA, Howard, K, et al. Exercise for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2019) 2019:CD012424. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012424

19. Goodwin, VA, Abbott, RA, Whear, R, Bethel, A, Ukoumunne, OC, Thompson-Coon, J, et al. Multiple Component Interventions for Preventing Falls and Fall-Related Injuries Among Older People: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Geriatr (2014) 14(15):15. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-14-15

20. Foster, M, Mitchell, R, and McClure, R. Chapter 17: Making Policy. In: McClure, R, Stevenson, M, and McEvoy, S, editors. The Scientific Basis of Injury Prevention and Control. Melbourne: IP Communications (2004).

21.ScottWorld Health Organization (WHO). Falls Prevention: Policy, Research and Practice (2007). Backgroound Paper for the WHO Report on Falls in Older Age.

22. Swahn, MH, Hankin, A, and Houry, D. Using Policy to Strengthen the Reach and Impact of Injury Prevention Efforts. West J Emerg Med (2011) 12(3):268–70.

23. Parekh, N, Mitis, F, and Sethi, D. Progress in Preventing Injuries: a Content Analysis of National Policies in Europe. Int J Inj Control Saf Promot (2014) 22(3):232–42. doi:10.1080/17457300.2014.909498

24. Stephenson, J. Gap between Falls Prevention Policies and Practice Revealed. Nurs Times (2015) 111(43):6–incomplete.

25. Birkland, T. An Introduction to the Policy Process: Theories, Concepts and Models of Public Policy Making. 4th ed. New York and London: Routledge (2016).

26. Palmer, G, and Short, S. Health Care and Public Policy: An Australian Analysis. 5th ed. South Yarra, VIC: Palgrave Australia Print. (2014).

27. Althaus, C, Bridgman, P, and Davis, G. The Australian Policy Handbook. 4th ed. Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin (2007).

28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Using Evaluation to Inform CDCs Policy Process. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services (2014).

29. Moller, J. Changing Health Resource Demands for Injury Due to Falls in an Ageing Population. N S W Public Health Bull (2002) 13(1-2):3–6. doi:10.1071/nb02003

30. Cheung, KK, Mirzaei, M, and Leeder, S. Health Policy Analysis: a Tool to Evaluate in Policy Documents the Alignment between Policy Statements and Intended Outcomes. Aust Health Rev (2010) 34(4):405–13. doi:10.1071/AH09767

31. Collins, T. Health Policy Analysis: a Simple Tool for Policy Makers. Public Health (2005) 119:192–6. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.006

32. Gilson, L. Qualitative Research Synthesis for Health Policy Analysis: what Does it Entail and what Does it Offer? Health Policy Plan (2014) 29:iii1–iii5. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu121

33. Levine, S, and Lilienfeld, AM, editors. Epidemiology and Health Policy. London: Tavistock Publications (1987).

34. Morestin, F, National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (NCCHPP). A Framework for Analysing Public Policies: Practical Guide. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy (2013).

35. Oh, A, Abazeed, A, and Chambers, DA. Policy Implementation Science to advance Population Health: the Potential for Learning Health Policy Systems. Front Public Health (2021) 9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.681602

36. Porche, DJ. Public Health Policy Analysis and Evaluation, Chapter 25. In: Public & Community Health Nursing Practice: A Population-Based Approach. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2004).

37. Rütten, A, Lüschen, G, von Lengerke, T, Abel, T, Kannas, L, Rodriguez Diaz, JA, et al. Determinants of Health Policy Impact: A Theoretical Framework for Policy Analysis. Soz.-Präventivmed. (2003) 48(5):293–300. doi:10.1007/s00038-003-2118-3

38. Hudson, B, Hunter, D, and Peckham, S. Policy Failure and the Policy-Implementation gap: Can Policy Support Programs Help? Pol Des Pract (2019) 2(1):1–14. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378

39. Knoepfel, P, Larrue, C, Varone, F, and Hill, M. Public Policy Analysis. Bristol, England: Bristol University Press (2007).

40. Walt, G, and Gilson, L. Reforming the Health Sector in Developing Countries: the central Role of Policy Analysis. Health Policy Plan (1994) 9(4):353–70. doi:10.1093/heapol/9.4.353

41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC). Step by Step - Evaluating Violence and Injury Prevnetion Policies. Brief 3 - Evaluating Policy Content. Washington, D.C, US: US Department of Health and Human Services (2013).

42. Kristianssen, A-C, Andersson, R, Belin, M-Å, and Nilsen, P. Swedish Vision Zero Policies for Safety - A Comparative Policy Content Analysis. Saf Sci (2018) 103:260–9. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2017.11.005

43. Walt, G, Shiffman, J, Schneider, H, Murray, SF, Brugha, R, and Gilson, L. 'Doing' Health Policy Analysis: Methodological and Conceptual Reflections and Challenges. Health Policy Plan (2008) 23:308–17. doi:10.1093/heapol/czn024

44. Zardo, P, and Collie, A. Measuring Use of Research Evidence in Public Health Policy: a Policy Content Analysis. BMC Public Health (2014) 14. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-496

45. Schopper, D, Lormand, J-D, and Waxweiler, R, World Health Organization. Developing Policies to Prevent Injuries and Violence: Guidelines for Policy-Makers and Planners. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2006). 74.

46. Brajshori, B. Public Policy Analysis and the Criteria for Evaluation of the Public Policy. Eur J Econ L Soc Sci (2017) 1(2):50–8.

47. Frieden, TR. Six Components Necessary for Effective Public Health Program Implementation. Am J Public Health (2014) 104(1):17–22. doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301608

48. Lesh, M. Evidence Based Policy Research Project - 20 Case Studies. Institute of Public Affairs Research (2018).

50. Washington, S, and Mintrom, M. Strengthening Policy Capability: New Zealand's Policy Project. Pol Des Pract (2018) 1(1):30–46. doi:10.1080/25741292.2018.1425086

51. Arksey, H, and O'Malley, L. Scoping Studies: towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol (2005) 8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

52. Levac, D, Colquhoun, H, and O'Brien, KK. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implementation Sci (2010) 5(69):1–9. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

53. Peters, MDJ, Marnie, C, Tricco, AC, Pollock, D, Munn, Z, Alexander, L, et al. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid Synth (2020) 18(10):2119–26. doi:10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

54. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med (2018) 169:467–73. doi:10.7326/M18-0850

55. Hadfield, R. Mediwrite. Pearl Growing in Systematic Literature Searching - what, Why and How (2020). Available from: https://www.mediwrite.com.au/medical-writing/pearl-growing/.

56. Vedula, S, Mahendraratnam, N, Rutkow, L, Kaufmann, C, Rosman, L, Twose, C, et al. A Snowballing Technique to Ensure Comprehensiveness of Search for Systematic Reviews: A Case Study. In: Abstracts of the 19th Cochrane Colloquium; 19-22 Oct 2011; Madrid, Spain (2011).

57. Wohlin, C. Guidelines for Snowballing in Systematic Literature Studies and a Replication in Software Engineering. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering - EASE '14; May 13 - 14, 2014; London, England (2014). p. 1–10.

58. Colebatch, H. Policy: Concepts in the Social Sciences. Buckingham: Open University Press (2002).

59.National Public Health Partnership (NPHP). The National Falls Prevention Plan 2004 Onwards. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2005).

60.Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC). Developing Papers with the Policy Quality Framework: Checklist for Reviewing Papers in Development. In: The Policy Project. Wellington: Government of New Zealand (2019).

61. Beattie, BL. The National Falls Free Initiative, Working Collaboratively to Affect Change. J Saf Res (2011) 42(6):521–3. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2010.11.009

62. Clemson, L, Finch, CF, Hill, KD, and Lewin, G. Fall Prevention in Australia: Policies and Activities. Clin Geriatr Med (2010) 26(4):733–49. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.07.002

63. Kennedy, A. A Critical Analysis of the NSF for Older People Standard 6: Falls. Br J Nurs (2010) 19(8):505–10. doi:10.12968/bjon.2010.19.8.47635

64. Schneider, EC, Smith, ML, Ory, MG, Altpeter, M, Beattie, L, Scheirer, MA, et al. State Fall Prevention Coalitions as Systems Change Agents. Health Promot Pract (2015) 17(2):244–53. doi:10.1177/1524839915610317

65. Lord, SR, Sherrington, C, Cameron, ID, and Close, JCT. Implementing Falls Prevention Research into Policy and Practice in Australia: Past, Present and Future. J Saf Res (2011) 42(6):517–20. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2010.11.008

66. Pynoos, J, Siciliano, M, and Beattie, BL. States Stand up for Fall Prevention: A Progress Report. Generations (San Francisco, Calif) (2008) 32(3):16–21.

67. Scott, V, Herman, M, Gallagher, E, and Sum, A. The Evolution of Falls and Injury Prevention Among Seniors in British Columbia, Canada. Open Longevity Sci (2011) 5:16–25.

68. de Jonge, D, Ainsworth, E, Tanner, B, Mann, WC, and Helal, A. Home Modifications Down under. Promoting Independence Old Persons Disabilities (2006) 18:155–68.

69.Department of Health and Human Services US. Healthy People 2020. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2010). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2020.htm.

70. Gormley, KJ. Falls Prevention and Support: Translating Research, Integrating Services and Promoting the Contribution of Service Users for Quality and Innovative Programmes of Care. Int J Old People Nurs (2011) 6(4):307–14. doi:10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00303.x

71. Beattie, BL. NEW LAW, FALLS FREE INITIATIVE, HELP STOP SENIORS' FREE FALL. Aging Today (2008) 29(4):9–10.

72. Campbell, AJ, and Robertson, MC. Comprehensive Approach to Fall Prevention on a National Level: New Zealand. Clin Geriatr Med (2010) 26(4):719–31. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2010.06.004

73. Hua, F, Yoshida, S, Junling, G, and Hui, P. Falls Prevention in Older Age in Western pacific Asia Region (Includes Japan & Australia) (2007).

74. Zaidi, A, and Howse, K. The Policy Discourse of Active Ageing: Some Reflections. Popul Ageing (2017) 10:1–10. doi:10.1007/s12062-017-9174-6

75. Oliver, TR. The Politics of Public Health Policy. Annu Rev Public Health (2006) 27:195–233. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123126

76. Zahariadis, NE. Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar (2016). p. 512.

77. Mitchell, R, and McClure, R. The Development of National Injury Prevention Policy in the Australian Health Sector: and the Unmet Challenges of Participation and Implementation. Aust N Z Health Pol (2006) 3(11):6. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-3-11

78. Sethi, D, and Mitis, F. APOLLO Policy Briefing: Using Advocacy for Injury Prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2009).

79. Davies, N, Atkins, G, and Sodhi, S. Using Targets to Influence Public Services. London, UK: Institute for Government (2021).

80. Day, L, Finch, CF, Hill, KD, Haines, TP, Clemson, L, Thomas, M, et al. A Protocol for Evidence-Based Targeting and Evaluation of Statewide Strategies for Preventing Falls Among Community-Dwelling Older People in Victoria, Australia. Inj Prev (2011) 17(2):e3. doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030775

81. Finch, CF, Stephan, K, Shee, AW, Hill, K, Haines, TP, Clemson, L, et al. Identifying Clusters of Falls-Related Hospital Admissions to Inform Population Targets for Prioritising Falls Prevention Programmes. Inj Prev (2015) 21:254–9. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041351

82. Kelsey, JL, Procter-Gray, E, Hannan, MT, and Li, W. Heterogeneity of Falls Among Older Adults: Implications for Public Health Prevention. Am J Public Health (2012) 102(11):2149–56. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300677

83.Department of Health and Human Services US. HHS Strategic Plan 2018-2022 - Strategic Goal 3: Strengthen the Economic and Social Well-Being of Americans across the Lifespan. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018).

84. Vu, TDT. Falls Prevention in Community-Dwelling Older People with Co-morbidity - a Targeted Approach. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University (2012).

85. Ward, H. Should Injury Prevention Programmes Be Targeted? Inj Prev (1997) 3:160–2. doi:10.1136/ip.3.3.160

86. Curtain, R. Good Public Policy Making - How Australia Fares. J Pol Anal Reform (2000) 8(1):33–46.

87. Holmes, B. Citizens' Engagement in Policymaking and the Design of Public Services: Research Paper no.1: Commonwealth of Australia. Australia: Department of Parliamentary Services. (2011).

88. Mooney, G, Angell, B, and Pares, J. Priority-setting Methods to Inform Prioritisation: An Evidence Check Rapid Review Brokered by the Sax Institute for the NSW Treasury and the Agency for Clinical Innovation. Glebe, Australia: The Sax Institute (2012).

89. Baggott, R. Policy Success and Public Health: The Case of Public Health in England. J Soc Pol (2012) 41(2):391–408. doi:10.1017/s0047279411000985

90.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Ten Great Public Health Achievements — United States, 2001–2010. Report No.: 0149-2195 Contract No.: 19. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services (2011).

91.Public Health Association of Australia (PHAA). Top 10 Public Health Successes over the Last 20 Years. Canberra, Australia: Public Health Association of Australia (2018).

92.World Health Organization (WHO) Europe. Successes and Failures of Health Policy in Europe. Four Decades of Divergent Trends and Converging Challenges. New York, NY: World Health Organization and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (2013).

93.Victorian Institute for Forensic Medicine (VIFM), Hyder, AA. Professory Adnan A. Hyder Gives the Graeme Schofield Oration: Injury Prevention and Public Health Research in the 21st Century. 19 September 2018. Unpublished. Melbourne, Australia: Graeme Schofield Oration (2018).

94.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). Clinical Data Systems and Older Adult Falls Surveillance. Arlington, VA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2017).

95.Injury Surveillance Workgroup on Falls (ISW4). Consensus Recommendations for Surveillance of Falls and Fall-Related Injuries. Atlanta, GA: State and Territorial Injury Prevention Directors Association (2006).

96. Mirani, N, Ayatollahi, H, and Khorasani-Zavareh, D. Injury Surveillance Information System: A Review of the System Requirements. Chin J Traumatol (2020) 23(3):168–75. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2020.04.001

97. Ganz, DA, Higashi, T, and Rubenstein, LZ. Monitoring Falls in Cohort Studies of Community-Dwelling Older People: Effect of the Recall Interval. J Am Geriatr Soc (2005) 53(12):2190–4. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00509.x

98. Hannan, MT, Gagnon, MM, Aneja, J, Jones, RN, Cupples, LA, Lipsitz, LA, et al. Optimizing the Tracking of Falls in Studies of Older Participants: Comparison of Quarterly Telephone Recall with Monthly Falls Calendars in the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Am J Epidemiol (2010) 171(9):1031–6. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq024

99. Campbell, S, Harper, G, and Treasury, HM. Quality in Policy Impact Evaluation: Understanding the Effects of Policy from Other Influences (Supplementary Magenta Book Guidance). London: HM Treasury (2012).

100. Chriqui, JF, O'Connor, JC, and Chaloupka, FJ. What Gets Measured, Gets Changed: Evaluating Law and Policy for Maximum Impact. J L Med. Ethics (2011) 39(S1):21–6. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00559.x

101. Peters, DH, Adam, T, Alonge, O, Agyepong, IA, and Tran, N. Republished Research: Implementation Research: what it Is and How to Do it. Br J Sports Med (2014) 48(8):731–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6753

102.National Public Health Partnership (NPHP). National Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion Plan 2004-2014. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2005).

103. Hill, KD, Vrantsidis, F, Clemson, L, Lovarini, M, and Russell, M, and Department of Health Victoria. Community Falls Prevention Program Sustainability Guidelines. In: Supporting Document to the NHMRC Partnership Grant 'Reducing Falls Among Older People in Victoria: Better Evidence, Better Targeting, Better Outcomes'. Melbourne, VIC: Department of Health Victoria. (2011).

104.Department of Health and Ageing. Don't Fall for it. Falls Can Be Prevented! A Guide to Preventing Falls for Older People. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2011).

105.Department of Health. National Injury Prevention Strategy 2020-2030: Draft for Consultation. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (2020).

106.NSW Health Department. Prevention of Falls and Harm from Falls Among Older People, 2011-2015. Sydney: Government of New South Wales (2011).

107.NSW Health Department. NSW Management Policy to Reduce Fall Injury Among Older People 2003-2007. Sydney: Government of New South Wales (2005).

108.QLD Department of Health, Division of the Chief Health Officer. Strategic Directions for Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion 2009-2012. Brisbane: Government of Queensland (2009).

109.Department of Health and Human Services Victoria. Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2011-2015. Melbourne: State of Victoria (2011).

110.Department of Health and Human Services Victoria. Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2015-2019. Melbourne: State of Victoria (2015).

111.Department of Health and Human Services Victoria, Prevention and Population Health Branch. Victorian Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2019-2023. Melbourne: State of Victoria (2019).

112.WA Health Department. WA Health Promotion Strategic Framework 2012-2016. Perth: Government of Western Australia (2012).

113.WA Health Department. WA Health Promotion Strategic Framework 2017-2021. Perth: Government of Western Australia (2017).

114.Government of Canada. Healthy Aging in Canada: A New Vision, a Vital Investment. A Discussion Brief Prepared for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Committee of Officials (Seniors). Government of Canada (2006).

117.Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on Seniors' Falls in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Public Health Agency of Canada (2005).

118.Public Health Agency of Canada. Seniors' Falls in Canada. Second Report. Ottawa: Government of Canada (2014).

119.BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit, Ministry of Health, Scott, V, Fiala, B, Yassin, Y, and Fekdman, F, The Next Wave of Fall Prevention in British Columbia: A Special Report by the BC Fall and Injury Prevention Coalition. Vancouver, BC: BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit and Ministry of Health (2014).

120.People's Republic of China, The State Council. National Action Plan for Disability Prevention in China 2016-2020. China: The State Council (2016).

121.People's Republic of China. Law of the People's Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly (1996). [Available from: http://www.china.org.cn/government/laws/2007-04/17/content_1207404.htm.

122.National Health and Family Planning Commission, Zhuang, N. Outline of the Healthy China 2030 Plan. People's Republic of China: National Health and Family Planning Commission (2016).

123.European Commission. European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP-AHA), A2 Falls Prevention Group. Belgium: European Commission (2011).

124.European Commission. European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP-AHA), A2 Falls Prevention Group. In: Action Plan A2 on Specific Action on Innnovation in Support of 'Personalised Health Management, Starting with a Falls Prevention Initiative'. Belgium: European Commission. (2013).

125.European Stakeholders Alliance for Active Ageing through Falls Prevention (ESA on Falls Alliance), Prevention of Falls Network for Dissemination (ProFouND). Alliance. E. Active Ageing through Preventing Falls: "Falls Prevention Is Everyone's Business. In: Joint Declaration. Netherlands: EuroSafe. (2015).

126.Netherlands Ministry of Health. Landelijke Nota Gezondheidsbeleid LNG 2020-2024 (National Health Policy 2020-2024). Netherlands, Europe: Government of Netherlands (2020).

127.Controller and Auditor-General NZ. The Accident Compensation Corporation's Leadership in the Implementation of the National Falls Prevention Strategy. In: Performance Audit Report. Wellington: Office of the Auditor-General (2008).

128. Smeh, D, and Bonokoski, N. New Zealand Injury Prevention Strategy. In: Casebook of Traumatic Injury Prevention. Switzerland: Springer Nature (2020). p. 519–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27419-1_35

129.Associate Minister of Health. Healthy Ageing Strategy. Wellington: Government of New Zealand (2016).

130.Singapore Ministry of Health. The Ministerial Committee on Ageing. I Feel Young in My Singapore. Action Plan for Successful Ageing. Singapore: Ministry of Health (2018).

131.Public Health England. Falls and Fracture Consensus Statement: Supporting Commissioning for Prevention (And Resource Pack). London: Crown (2017).

132.Health Service Executive. National Council on Ageing and Older People, Department of Health and Children. Strategy to Prevent Falls and Fractures in Ireland's Ageing Population. In: Report of the National Steering Group on the Prevention of Falls in Older People and the Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis throughout Life. Ireland, Europe: Government of Ireland (2008).

133.Scottish Government. The Prevention and Management of Falls in the Community: A Framework for Action in Scotland 2014/2016. Edinburgh: Crown (2014).

134.Scottish Government, Chief Nursing Officer's Directorate. Fall and Fracture Prevention Strategy for Scotland, 2019-2024: Consultation Version. Edinburgh: Crown (2019).

135.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), Stevens, J. A CDC Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. Altanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015).

136.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementation of Effective Community-Based Falls Prevention Programs. 2nd ed. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. (2015).

137.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC). STEADI - Older Adult Falls Prevention: Patient & Caregiver Resources: What You Can Do to Prevent Falls. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017).

138.National Council on Aging (NCOA). Falls Free: Promoting a National Falls Preventions Action Plan. Washington, DC: NCOA (2005).

139.National Council on Aging (NCOA), Cameron, K, Schneider, ES, Childress, D, and Gilchrist, C. Falls Free: 2015 National Falls Prevention Action Plan. Washington, DC: NCOA (2015).

140.National Council of Aging (NCOA), Beattie, BL, and Schneider, ES. State Policy Toolkit for Advancing Fall Prevention. Washington, DC: NCOA (2012).

141.National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy: America's Plan for Better Health and Wellness. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services US, Office of the Surgeon General (2011).

142.National Prevention Council. Healthy Aging in Action: Advancing the National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General (2016).

143.United States Senate. Special Committee on Aging. Falls Prevention: National, State, and Local Solutions to Better Support Seniors. Washington, DC: Congressional Publications (2019).

144.Department of Health and Human Services US. Administration for Community Living (ACL). 2016 Older Americans Act (OAA) Reauthorization Act (P.L. 114-144). ACL's Overview of Key Changes. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016).

145.Department of Health and Human Services US. Healthy People 2030. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2020). [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_people/hp2030/hp2030.htm.

Keywords: older adults, injury prevention, falls prevention, community setting, public health policy, policy analysis

Citation: Natora AH, Oxley J, Barclay L, Taylor K, Bolam B and Haines TP (2022) Improving Policy for the Prevention of Falls Among Community-Dwelling Older People—A Scoping Review and Quality Assessment of International National and State Level Public Policies. Int J Public Health 67:1604604. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604604

Received: 11 November 2021; Accepted: 16 May 2022;

Published: 27 June 2022.

Edited by:

Gabriel Gulis, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkReviewed by:

Tuo-Yu Chen, Taipei Medical University, TaiwanNiki Fairhal, The University of Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Natora, Oxley, Barclay, Taylor, Bolam and Haines. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aleksandra H. Natora, YWxla3NhbmRyYS5uYXRvcmFAbW9uYXNoLmVkdQ==; Jennifer Oxley, amVubmllLm94bGV5QG1vbmFzaC5lZHU=

Aleksandra H. Natora

Aleksandra H. Natora Jennifer Oxley1*

Jennifer Oxley1*