- 1Institute of Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2School of Design and Creative Arts, Loughborough University, Loughborough, United Kingdom

Objectives: Studies of storytelling (ST) used as a research tool to extract information and/or as an intervention to effect change in the public knowledge, attitudes, and behavior/practice (KAB/P) were sought and analyzed.

Methods: Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, ERIC, Web of Science, Art and Humanities database, Scopus, and Google Scholar were searched, and a basic and broad quantitative analysis was performed, followed by an in-depth narrative synthesis of studies on carefully selected topics.

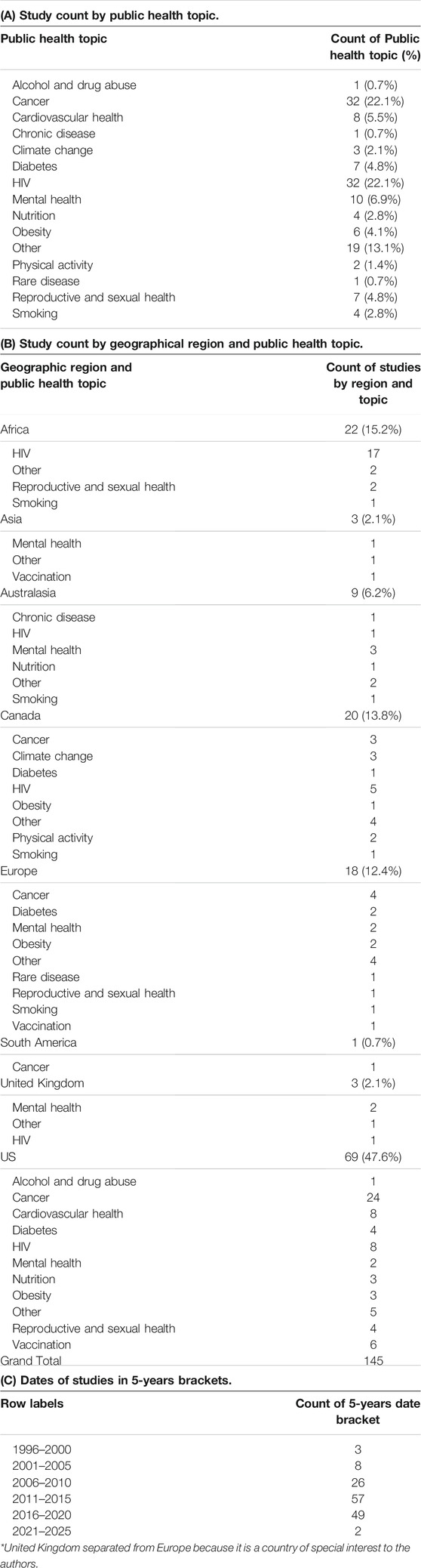

Results: From this search, 3,077 studies were identified. 145 studies entered quantitative analysis [cancer and cancer screening (32/145), HIV (32/145), mental health (10/145), vaccination (8/145), and climate change (3/145)]. Ten studies entered final analysis [HIV/AIDs (5), climate change (1), sexual health (3), and croup (1)]. ST techniques included digital ST (DST), written ST, verbal ST, and use of professional writers. Of the ten studies, seven used ST to change KAB/P; the remainder used ST to extract insights. Follow-up and evaluation were very limited.

Conclusion: ST reveals insights and serves as an intervention in public health. Benefits of ST largely outweigh the limitations, but more follow-up/evaluation is needed. ST should play a more significant role in tackling public health issues.

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019124704

Introduction

The properties of storytelling (ST) are such that a personal experience, told with nuanced detail, resonates with the listener and may even validate their own experiences, helping them and the teller make sense both retrospectively and prospectively of real-life events [1].

Back in 1964, phenomenologist Maurice Merleau Ponty wrote that the making of stories, “reveals things to us that we know but didn’t know we knew”, suggesting that ST provides access to a richness of information not necessarily available via other means [2].

Increasingly, ST is used as a methodological tool in research, including that of health and social science [3–6]. It is likely that many incidences of ST in health research remain undocumented for reasons of confidentiality.

In many contexts, storytelling might be considered as lying outside the arena of entertainment. Lugmayr et al refer to such “serious storytelling” as narration that “progresses as a sequence of patterns impressive in quality, relates to a serious context, and is a matter of thoughtful process.” [7] ST with purpose beyond entertainment is one focus of this review, that is, ST as a research tool in public health.

It also addresses both the development of a story and the process of telling it. Many ST studies have employed narrative-as-message (story as text without detail on the process of telling) but few have explored how people identify, craft, and tell their personal stories. Fewer still are studies on the assessment of ST as a tool for change in knowledge, attitude and, behavior/practice (KAB/P).

ST formats vary and include verbal, written, “photovoice” (use of photos as prompts), or, increasingly, digital storytelling (DST), which captures lived personal experiences through the creation of 3–5-min digital films.

DST may manifest as digital video, gaming, Instagram stories (or “Instastories”), or interactive television as examples. Within the boundaries of this review, DST primarily refers to the production of a short (3–4 min) digital video where participants craft personal experiences, possibly using photo, music, and voice recordings [8].

As a research tool, ST generates more nuanced, contextualized, and culturally-reflective information than some other qualitative research methods, e.g., interview, but it can also be used as an intervention to facilitate change in KAB/P. In this respect, the transformative properties of ST can be conceived as relating to the stimulation of human emotions to engage with new knowledge and, as such, influence attitude and ultimately behavior, as illustrated by Wong J. P. et al in the prevention of HIV/sexually transmitted infections (STIs). ST contextualizes health-related information to one’s own situation, potentially encouraging beneficial behavioral change [9].

Conventionally, social and health research largely uses quantitative cross-sectional surveys to measure change in KAB/P, while most qualitative work exploring KAB/P involves interviews and/or focus groups. For example, with antimicrobial resistance (AMR), most research on the KAB/P adopts health behavior surveys [10], interviews, and focus groups [11, 12]. The researchers are particularly interested in AMR and intend to use ST as a future research tool on the topic. No studies were identified using ST to explore AMR.

ST largely remains an emergent research method and its validity has not been established. However, this does not justify dismissing the potential value of ST in this capacity, and this review aimed to identify evidence of the validity of ST as used in the research context whether to gather information and/or used as an intervention to change KAB/P.

In summary, this systematic review aimed to, firstly, conduct a basic quantitative evaluation of the distribution of peer-reviewed, published studies that use ST as a research tool across a broad range of public health issues and, secondly, to qualitatively analyze 10 carefully selected studies that use ST as 1) a research tool to gain insight into KAB/P, and/or 2) an intervention to effect change. Essentially, the public health issues selected for final analysis were defined as bearing a personal cost in the immediate term but potentially providing a population-level health benefit in the long-term, for example, vaccination or AMR (foregoing an antibiotic in the short-term to help prevent the development of resistance at a population level in the long-term). The review was conducted using the process of narrative synthesis and was designed to inform future research using ST in AMR.

Methods

Sources

Peer-reviewed and published studies were identified from eight major databases: Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC (Proquest), Web of Science, Art and Humanities database (ProQuest), Scopus, and Google Scholar. Two librarians aided formulation of the search strategies. Key words and synonyms can be found in Table 1.

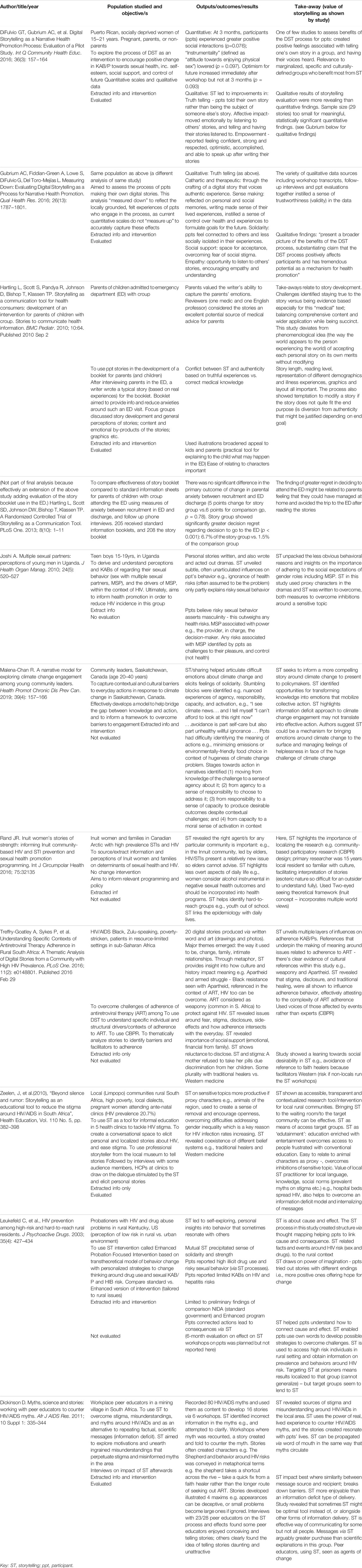

TABLE 1. Search terms comprised of concepts and synonyms (broadly based on PICO), United Kingdom, 2021.

Study Selection and Screening

Endnote reference management software was used to organize studies and systematic review management software (SUMARI) [13] aided initial title and abstract screening (BM and CF). Full texts were reviewed and reference lists checked (BM and CF). The recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) were followed.

Inclusion Criteria

The stage 1, basic, quantitative analysis included all studies that met the following inclusion criteria: qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method, peer-reviewed, primary public health studies using ST within the context of research and in the English language; publication 1990–present; all ages and demographic backgrounds; and ST (verbal or written or digital) used as a research tool to understand and/or effect change in KAB/P.

The stage 2, qualitative analysis included studies that primarily addressed public health topics involving a personal cost in the immediate term but population-level health benefit in the longer term e.g., HIV involves individual sacrifice of testing in the short-term but reduced HIV population-level spread in the long-term. This criterion parallels the nature of AMR–an area of research interest to the authors. Other inclusion criteria are in Supplementary File S1.

Definitions used in screening and selection were: story–a story derived from interviews, role model stories, or narrative accounts; storytelling–DST, “Photovoice”, plays, theatre, or film, usually involves the crafting and telling of a story; and personal narrative–personal experience not formatted as a story.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies where health was a secondary consideration, or subject matter was more clinical than public health, were excluded.

Critical Appraisal of Selected Studies

Critical appraisal of included studies used the 16-item QATSDD tool for qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies [14]. This provides a score (0 = very poor, 3 = very good) for each criteria in each study, and an overall score.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

JBI SUMARI [13] software helped data extraction from the 145 studies in the quantitative analysis, and the 10 final studies (Supplementary Files S2A, S2B respectively). The latter included phenomena of interest, overall design/methods (using ST) and analysis, location, setting including context/culture, participant characteristics, sample size, and description of main results.

Data synthesis used the narrative synthesis approach developed by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) [15], comprising an initial description of study results describing patterns observed (preliminary synthesis), followed by an exploration of relationships within and between studies, as well as interpretations and possible explanations (narrative synthesis).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the narrative synthesis review of the 10 final studies. Secondary outcomes were drawn from the 145 studies for quantitative review and included, for example, frequency of the public health topics by storytelling method, the geographical spread stratified by topic, and study dates.

Results

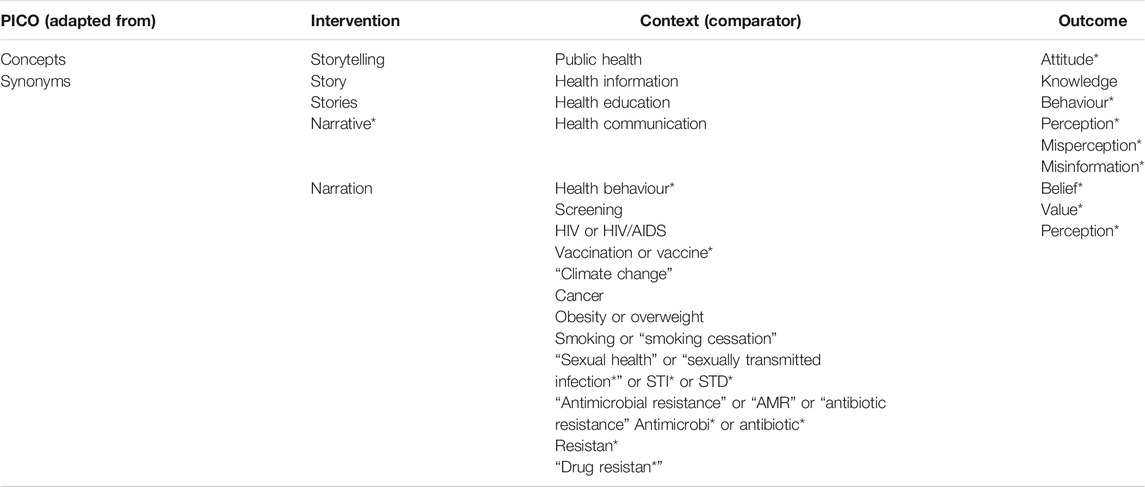

The initial search for studies using stories, ST, or personal narrative in the public health arena provided a total of 3,077 studies, after removal of duplicates. All of these were title and abstract screened (necessary for sufficient information), and 2,852 were removed due to the following (Supplementary File S3: Reasons for exclusion): being off topic (1072), having an unsuitable method (439), subject matter a poor fit for the inclusion criteria (1,073), study paper unobtainable or a conference abstract only (13) not a primary study (160), or topic not associated with short-term personal sacrifice and long-term population level gain (95). Full text review involved 216 studies.

Insert: Figure 1: PRISMA flow chart representing selection process for the use of storytelling as a tool to extract information or as an intervention across a range of public health issues. Studies (145) in the quantitative analysis are in blue, while those (10) in the final analysis are in black. United Kingdom, 2021.

FIGURE 1. PRISMA flow chart representing selection process for the use of storytelling as a tool to extract information or as an intervention across a range of public health issues. Studies (145) in the quantitative analysis are in blue, while those [10] in the final analysis are in black. United Kingdom, 2021.

Critical Appraisal of Studies in the Final Analysis

Critical appraisal of the 10 studies included for final analysis was challenging due to the heterogeneity of methods and the subjectivity of the qualitative content (8/10 studies contained qualitative data only; 2/10 contained qualitative and quantitative data). See Supplementary Files S4A, S4B for critical appraisal scores.

Each study was scored according to the relevant criteria. Qualitative studies were assessed using 13/16 total criteria, while mixed-method studies used 16/16 criteria. Qualitative only (8/10 studies) generated an overall score of 64%, and mixed method (2/10 studies) generated the highest overall score of 70%. The overall score for all studies combined reflected a weighting towards qualitative data at 66% that drew strength from detailed descriptions of context and setting and articulated thematic descriptions and interpretations.

Study Characteristics

Quantitative Analysis

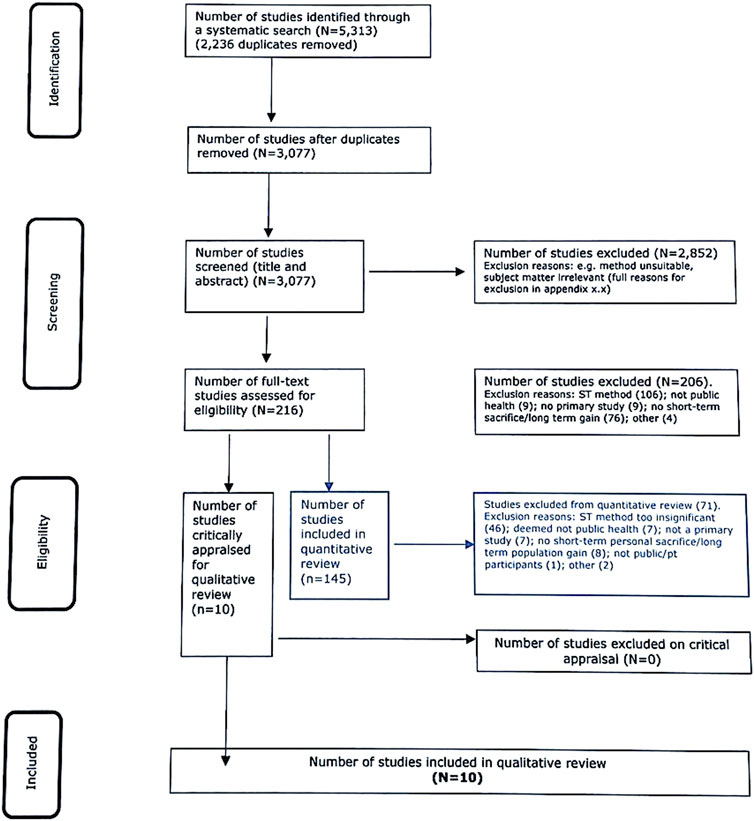

Of 145 studies identified, ST comprised 80/145 (54.8%), story 44/145 (30.1%), and personal narrative 21/145 (14.4%) as research tools to address a total of 16 public health topics.

Cancer/cancer screening comprised most studies 32/145 (22.1%) matched by HIV 32/145 (22.1%); the remaining studies focused on mental health 10/145 (6.8%), cardiovascular health 8/145 (5.5%), and vaccination 8/145 (5.5%). No studies referred to AMR.

Analysis by study location showed that 69/145 (47.6%) were based in the United States (US), 22/145 (152%) in Africa, 20/145 (13.8%) in Canada, 18/145 (12.4%) in Europe, 9/145 (6.2%) in Australasia, and only 4/145 (2.8%) in the United Kingdom (UK).

Study dates showed a leap in the number of studies from 8 in 2001–2005, to 26 in 2006–2010, and then doubling to 57 studies in 2011–2015 and 49 in 2016–2019 see Table 2 for a breakdown of quantitative findings.

TABLE 2. Number of studies by public health topic, geographical region, and dates of studies, United Kingdom, 2021.

Final Qualitative Analysis of 10 Storytelling Studies

Study Characteristics

The 10 studies included in the final analysis all used ST as a qualitative research method. Two papers referred to one study, but were distinct enough to be counted as two studies [16, 17]. Use of ST was heterogeneous: as an intervention to effect change in 7/10 studies [18–22], and as a means to extract information (3/10) [23–25]. Topics included HIV (5/10 studies) [18, 20, 22, 23, 25], sexual and reproductive health (3/10) [16, 17, 24], climate change (1/10) [21], and emergency care of croup (1/10) [19]. Of the studies, three out of ten used DST [16, 17, 25], two out of ten employed a professional storyteller to craft and perform participants’ stories [19, 22], two employed ST by written word [21, 24], and three used verbal ST [18, 20, 23]. Two out of ten studies used mixed methods using both quantitative and qualitative data [16, 17] while eight primarily used qualitative data only [18–25]. The locations used were Uganda (1/10) [24], the US (3/10); [16, 17, 20], Canada (3/10) [19, 21, 23], and South Africa (3/10) [18, 22, 25]. Participant numbers ranged from six to 200, with most involving around 25–30 participants. See Table 3 for key characteristics of the 10 studies and Supplementary File S5 for the list of studies for final analysis.

The Process of Storytelling

Considerable heterogeneity in ST methods remained within the 10 final studies. ST involves a process of triggering participant memories and crafting these into a story, e.g., in the climate change study, participants jotted down memories of personal experiences which were incorporated into their story [21]. Thought-mapping (nodes representing feelings, thoughts, and actions with lines between them denoting cause and effect) was a technique used to stimulate thinking around risk-taking behaviors [20].

Proxy characters including cards featuring characters of similar demographic to participants or animals instead of humans were used [22, 24]. South African miners aimed to dispel HIV stigma by gathering 300 local myths and using them to inform stories [18]. Images recorded pivotal moments to aid DST [17].

Storytelling as Agent of Change or Exploratory Tool

The majority (7/10) of studies served to both extract information and serve as an intervention.

The study exploring young Ugandan men’s attitudes towards multiple sexual partners (MSP) mainly sourced insights but briefly touched on intervention [24]. Changing the stigma around HIV/AIDS and STIs was central to a number of studies [18, 22, 25]. ST acted as an agent of change to correct misinformed, stigmatizing myths with factually correct stories [18]. ST was used to overcome challenges around adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV treatment [25].

Malena-Chan used Ganz’s narrative framework to gain a deeper understanding, through ST, about how barriers (narrative dissonance) and opportunities (narrative fidelity) arise and contribute towards the translation of knowledge on climate change into action [21].

ST by teenage Latino women encouraged positive change in sexual health attitudes and behaviors via DST. The impact of ST on participants found that women experienced improvement in positive social interactions, sense of empowerment, optimism, and control over their futures [16, 17].

Information and insights on the determinants of, and potential ways to, improve sexual health and HIV was sourced via ST in Inuit communities [23].

Reported Benefits of Using Storytelling as a Research Tool

The benefits of ST were evident from direct participant feedback or from feedback from authors. The teenage Latino women said DST provided them with a voice when they had so often felt shamed into silence, and an opportunity for them to reflect on their personal memories and make sense of their lives [16, 17].

ST also revealed nuanced insights, e.g., Ugandan young men revealed that ignorance of health risks was not the primary driver of STIs/HIV risk. Instead they felt that having MSP asserted their masculinity through entrenched cultural views, and this was the dominant factor in determining their health outcomes [24].

ST with respect to mitigating climate change uncovered various social, cultural, and structural barriers to taking action in the everyday lives of the residents of Saskatchewan, Canada. For example, the authors write “dissonance may result from a lack of perceived power to intervene meaningfully through individual roles,” such as struggling to find meaning behind personal actions which seemed insignificant given the scale and scope of the challenge of climate change.

A study exploring HIV stigma in South Africa used ST as an intervention in clinic waiting rooms to open a dialogue on the issue [22]. Interestingly, the stories generated by South African miners based on dispelling myths could easily be shared via word of mouth (effectively, via the same communication route that spread the misinformation initially) [18].

ST Aims, Methods, and Analysis of Stories

Only one study explicitly articulated a clear aim to their ST research project, comprising the use of stories as booklets to help patients understand the management of croup in the emergency department [19]. The aims of other studies were less clear but included informing future policy, e.g., on climate change [21], or sexual health/HIV [23], and improving understanding around health risks of unprotected sex and HIV risks of injectable drug use [20].

Thematic analysis was used by 8/10 studies to identify common themes across a number of stories [16, 17, 21–25]. Other methods of analysis included visual text analysis [25]; coding using participant input to develop over-riding themes [23]; analyses of descriptive statistics e.g., age, gender, and birthplace from surveys [16, 17]; and content analysis–the presence, meanings, and relationships between certain words, themes, or concepts to analyze a story about croup [19]. The study on climate change identified points of narrative dissonance (barriers) and narrative fidelity (facilitators) in the ST data to help frame challenges, choices, and outcomes regarding climate change action [21].

Discussion

In determining the value of ST as a qualitative research method in public health, a narrative synthesis was conducted.

Frameworks to guide the use of ST in research were noticeably absent across most studies, other than one used by Ganz in the study on climate change, which referred to the nestling of personal stories within public narratives based on relationships with others, cultural context, and shared values to convey meaning [21].

Storytelling’s Value in Extracting Information and Insights on KAB/P

ST elicits nuanced information and emotions that might be inaccessible via other means of qualitative or quantitative investigation, especially given the personal and public sensitivities around some topics e.g., HIV stigma. ST can reveal subtle insights on behavior e.g., those related to STI/HIV in Inuit communities that found men in the community were the hard-to-reach ones (for public health messages) and who lacked the social networks that women have through sewing groups and ante-natal groups [23]. Young men in Uganda at high risk for HIV through a lifestyle with MSP were more concerned about things that challenge their pleasure and masculinity than health risks, possibly indicating a need to consider gender power dynamics in any potential health intervention [24].

Storytelling’s Value as an Intervention to Change KAB/P

Follow-up time, across all studies, was too short to draw conclusions about the impact of ST in changing KAB/P. Changing behavior over the short and long-term is complex and any evaluation would need to reflect that [26].

However, marked positive effects of group ST were documented in the studies by Difulvio, Gubrium, Leukefeld, and Dickinson: women in the studies by Difulvio and Gubrium reported feeling enhanced positivity when telling their own story in a group setting, feeling less socially isolated, discovering more empathy, and, in particular, having the opportunity to have their voices heard [16, 17]. Likewise, positive change in KAB/P in probationers was reported, as structured ST led to insights into personal behavior that sometimes resonated with others [20].

All participants in the 10 studies were members of marginalized groups, and insights into the benefits of ST in changing KAB/P speaks to the finding elsewhere that marginalized groups often reap optimal benefit from ST activities. Researchers find personal stories can illuminate the nuances and the human aspects that underpin challenging social issues often involving marginalized groups [27].

Dickinson defines stories as agents of change that have the power to overcome stalemates around KAB/P relating to stigma, misunderstanding, and myths around HIV and AIDS [18].

The Storytelling Process and its Value as a Unique Research Tool

The 10 studies revealed that multiple processes could be followed to elicit a meaningful story.

Sensitivities around the public health topic of concern, as well demographics and cultural and/or social norms, were all instrumental in determining the nature of the ST process followed, including the actors deployed. Use of a professional storyteller can facilitate interactions around sensitive topics, e.g., Zeelen used a professional storyteller who created dialogues between animals as a metaphor for real people discussing HIV stigma in their community. Arguably, use of an intermediary agent might diminish the authenticity of the story eventually told because stories can adopt a new form with each telling. That stories are multiplicities, and ST is temporary in nature, whereby stories resist definition and documentation, is supported by core ST literature [28].

The significance of story authenticity also played out with respect to the inherent conflict between the accuracy of medical content versus authenticity of a personal story in the study on children with croup, where details around an X-ray were omitted for not being standard clinical practice [19].

The study in South African ante-natal clinic waiting rooms used a storyteller who knew the local language and culture, and referred to local animals to help listeners find meaning and internalize the messages about protective health behavior rather than just receive information, as per the information deficit model of imparting knowledge [29]. Joshi overcame inhibitions around discussing MSP and risk of HIV/STIs by using written stories and proxy characters [24].

ST reveals insights not necessarily accessible by other means, e.g., subtle cultural influences in health decision-making, providing something potentially additive to other qualitative or quantitative research. The study on climate change unearthed how barriers manifest within the narratives of people who appear to accept climate science, uncovering novel nuances of emotional and moral reasoning, and insights that might not have been readily available via other research methods [21].

Thought-mapping used with ST around drug use and sexual practices helped participants work through problems and solutions/strategies, providing the opportunity to create an alternative, more positive story end [20].

Data from the study by Gubrium supports the role of qualitative data as complementary to quantitative data. The author argues for the importance of reflecting the “locally grounded, felt experiences” of participants, as current quantitative scales do not measure up to accurately capture these effects [17].

The majority of studies in the quantitative review (145 studies) were from a chronic disease background that play out over an extended period of time, e.g., HIV and cancer together that comprised the majority of public health topics covered, followed by mental health. The quantitative analysis also showed that most studies were conducted in the US (47.6%) with cancer and cancer screening being most often studied (24/68 studies), possibly reflecting a dominant health concern in that country.

Cardiovascular health featured in only 8/68 studies, possibly suggesting a trend for ST in some areas of public health and scope to extend the range of public health areas which use ST as a research tool.

Finally, the study by Rand illustrates how ST and stories forge a bridge between the intricate realities of everyday lives (qualitative research) and quantitative epidemiology to provide both a close-up and wider view of the public health issue at stake and ultimately help formulate more effective public health interventions [23].

ST Lends Itself to Teasing out Nuanced Personal Experience

ST thrives on the nuances and non-explicit influences of cultural or ethnic nature. Here, studies featured participants defined by social deprivation, employment status, criminal record, local prevalence of HIV, teenage pregnancy or STIs, and descriptions of community hierarchies, to name a few.

Many of the ST cohorts belonged to hard-to-reach or vulnerable communities, for example, the probationers in rural Kentucky, US, of whom 61% had a history of drug convictions [20], or the teenage Puerto Rican women from an inner city in New England, US [16, 17].

Sensitive or controversial topics frequently form the focus of ST research projects because discussion around them is often avoided in communities precipitating misunderstanding and stigma. ST among probationers created a secure space for open discussion of drug use and HIV risk [20]. In the study in African ante-natal clinics, ST facilitated access to otherwise hard-to-reach members of the community [22].

Choice of facilitators and storytellers was also found to influence ST success. In the Inuit study, the workshop facilitator, a local settler and resident, had an ingrained understanding of the cultural nuances of participants’ lives, e.g., importantly, highly revered Inuit elders were included in the ST study [23].

Stories in the study of ART adherence in South Africa drew on cultural references and social norms, e.g., a belief that HIV medication echoes a subtheme around armed struggle, which alludes to the historical fight in South Africa against Apartheid. Weaponry was also referred to in the struggle to defeat HIV [25].

Prior reference to drawing on culture to tailor narrative research to the study population is made by Larkey and Hecht with their culture-centric, narrative theory-Narrative Communication Prevention Model [30]. This refers to how people structure reality, including health decisions, by telling stories that tap into implicit local cultural values and codes. This approach through the medium of ST can be more effective at reaching certain audiences who might be less involved, or even resistant to, the relevant message, and that narrative or ST might appeal where information provision does not.

Limitations of ST as a Research Method

The ‘validity’ of data generated by the studies is fundamental to the use of ST as a research tool, but interpretation of the term “validity” as used in qualitative studies is a challenging concept. Noble et al. parallel reliability and “consistency” with trustworthiness, suggesting a need for clarity around the methods undertaken with a “decision-trail” that is transparent enough for reproducibility. In the 10 studies chosen for final qualitative review, few studies satisfied these requirements. Gubrium came closest to a measure of trustworthiness or validity of the qualitative ST data generated by cross-referencing findings to a variety of data sources, for example, transcripts of key DST activities, individual interviews with participants, field notes from workshops, and workshop evaluations [17].

Treffry-Goatley attempted to “validate” storytelling by using triangulation with drawings and music [25].

The value of ST resides in taking the data on their own merit, without generalizing, unlike quantitative research. However, the study by Hartling demonstrates how authenticity can be lost in the effort to meet project objectives, when the story was modified to fit the end purpose-an information booklet [19].

Most ST studies lacked rigorous follow-up and evaluation even over the short term. Going forward, if ST is to be recognized as an effective research method, especially within health and medicine, far greater emphasis needs to be placed on evaluation. Some quantitative analysis might have value in assessing the impact of ST as a tool for research or as an intervention, as seen in the studies by Gubrium and Difulvio [16, 17]. Generally, health and medical research lends to quantitative analysis, e.g., assessing change in a certain clinical parameter, but in contrast, ST often comprises an individual’s perceived truth, and as such it is difficult to construct a measure of such a variable entity.

Strengths and Limitations of this Systematic Review

This review has several strengths. It was conducted transparently, following established guidelines and a prospectively specified protocol. Multiple databases were searched–covering science, humanities, and arts. To reduce the risk of missing relevant studies, two reviewers were involved (BM and CF).

Limitations to this review include that the topics entered into the full review (stage 2) had to satisfy the key criterion of short-term personal sacrifice with long-term population level gain in order to reflect aspects of the public health scenario presented by AMR. This excluded many studies that may have contained valuable information on ST process and value. ST is also a broad term that might have included stories as told via social media or in the mainstream and specialist media. This review was limited to the telling of personal stories.

A few studies using story, ST, or personal narrative were found in the last 18–24 months and were included in the quantitative analysis, for example, a study on beliefs and intentions behind flu vaccination uptake, however, none of these met the tight criteria for the final selection.

Conclusion

This review found evidence to support ST as having inherent value in revealing nuanced insights on a wide variety of public health topics and played an active role in participants making sense of real-life events and changing KAB/P. The review found most ST studies relate to chronic conditions, specifically HIV and cancer/cancer screening. By uncovering subtle influences on the development of KAB/P, ST lends itself to intractable public health issues that are strongly influenced by peripheral factors e.g., social norms and culture, specific to different communities.

Also, the review suggests that ST could play a more robust and formalized role in public health research. However, in this respect much greater attention is needed in ensuring solid evaluation of ST studies. The value of ST as additive to other qualitative and quantitative data cannot be overstated if a fully rounded and balanced perspective on a public health situation is sought to either inform an intervention or to serve as an intervention itself.

Author Contributions

The study was conceived by BM. BM developed the eligibility criteria, search strategy, risk of bias assessment strategy, and data extraction plan with guidance from AH, LS, and MW. Search and screening were conducted by BM and CF helped at the full-text review stage. BM wrote the manuscript, to which all authors contributed.

Funding

Medical Research Foundation (MRF) grant number MRF-145-0004-TPG-AVISO.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.ssph-journal.org/articles/10.3389/ijph.2021.1604262/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bruner, J. The Jerusalem-Harvard lectures.Acts of Meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.le (1990).

2. Merleau-Ponty, M, and Edie, JM. The Primacy of Perception : And Other Essays on Phenomenological Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History, and Politics. p. 228.

3.The Challenges of Being an Insider in Storytelling Research [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 12]. Available from: www.nurseresearcher.co.uk (Accessed March 25, 2020)

4. Lenette, C, Cox, L, and Brough, M. Digital Storytelling as a Social Work Tool: Learning from Ethnographic Research with Women from Refugee Backgrounds. Br J Soc Work (2015) 45(3):988–1005. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct184

5. Taylor, B. Hospice Nurses Tell Their Stories about a Good Death: the Value of Storytelling as a Qualitative Health Research Method. Annu Rev Health Soc Sci (1993) 3:97–108. doi:10.5172/hesr.1993.3.1.97

6. Bird, S, Wiles, JL, Okalik, L, Kilabuk, J, and Egeland, GM. Methodological Consideration of story Telling in Qualitative Research Involving Indigenous Peoples. Glob Health Promot (2009) 16(4):16–26. doi:10.1177/1757975909348111

7. Lugmayr, A, Sutinen, E, Suhonen, J, Sedano, CI, Hlavacs, H, and Montero, CS. Serious Storytelling – a First Definition and Review. Multimed Tools Appl (2017) 76(14). doi:10.1007/s11042-016-3865-5

8. Fiddian-Green, A, Kim, S, Gubrium, AC, Larkey, LK, and Peterson, JC. Restor(y)ing Health: A Conceptual Model of the Effects of Digital Storytelling. Health Promot Pract (2019) 20(4):502–12. doi:10.1177/1524839918825130

9. Wong, JP, Kteily-Hawa, R, Chambers, LA, Hari, S, Vijaya, C, and Suruthi, R. Exploring the Use of Fact-Based and story-based Learning Materials for HIV/STI Prevention and Sexual Health Promotion with South Asian Women in Toronto, Canada. Health Educ Res (2019) 34(1):27–37. doi:10.1093/her/cyy042

10. Haenssgen, MJ, Charoenboon, N, Zanello, G, Mayxay, M, Reed-Tsochas, F, and Lubell, Y. Antibiotic Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices: New Insights from Cross-Sectional Rural Health Behaviour Surveys in Low-Income and Middle-Income South-East Asia. BMJ Open (2019) 9:e028224. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028224

11. Van Hecke, O, Butler, CC, Wang, K, and Tonkin-Crine, S. Parents' Perceptions of Antibiotic Use and Antibiotic Resistance (PAUSE): a Qualitative Interview Study. J Antimicrob Chemother [Internet] (2019) 74(6):1741–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dkz091

12. Jones, LF, Owens, R, Sallis, A, Ashiru-Oredope, D, Thornley, T, and Francis, NA. Qualitative Study Using Interviews and Focus Groups to Explore the Current and Potential for Antimicrobial Stewardship in Community Pharmacy Informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework. BMJ Open (2018) 8(12):e025101–11. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025101

13.Joanna Briggs Institute. Checklist for Qualitative Research. Systematic Review Management Software (SUMARI) [Internet] (2017). [cited 2018 Dec 12]. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.htmlwww.joannabriggs.org (Accessed March 25, 2020).

14. Sirriyeh, R, Lawton, R, Gardner, P, and Armitage, G. Reviewing Studies with Diverse Designs: The Development and Evaluation of a New Tool. J Eval Clin Pract (2012) 18(4):746–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x

15. Rodgers, M, Arai, L, Britten, N, Petticrew, M, Popay, J, and Roberts, H. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews : A Comparison of Guidance-Led Narrative Synthesis versus Meta-Analysis" A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Version 1 (2006). p. 1–92.

16. Difulvio, GT, Gubrium, AC, Fiddian-Green, A, Lowe, SE, Marie, L, and Toro-Mejias, D. Digital Storytelling as a Narrative Health Promotion Process: Evaluation of a Pilot Study.

17. Gubrium, AC, Fiddian-Green, A, Lowe, S, DiFulvio, G, and Del Toro-Mejías, L. Measuring Down. Qual Health Res (2016) 26(13):1787–801. doi:10.1177/1049732316649353

18. Dickinson, D. Myths, Science and Stories: Working with Peer Educators to Counter HIV/AIDS Myths. Afr J AIDS Res (2011) 10(Suppl. 1):335–44. doi:10.2989/16085906.2011.637733

19. Hartling, L, Scott, S, Pandya, R, Johnson, D, Bishop, T, and Klassen, TP. Storytelling as a Communication Tool for Health Consumers: Development of an Intervention for Parents of Children with Croup. Stories to Communicate Health Information. BMC Pediatr (2010) 10(1):64. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-10-64

20. Leukefeld, C, Roberto, H, Hiller, M, Webster, M, Logan, T, and Staton-Tindall, M. HIV Prevention Among High-Risk and Hard-To-Reach Rural Residents. J Psychoactive Drugs (2003) 35(4):427–34. doi:10.1080/02791072.2003.10400489

21. Malena-Chan, R. A Narrative Model for Exploring Climate Change Engagement Among Young Community Leaders. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can (2019) 39(4):157–66. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.39.4.07

22. Zeelen, J, Wijbenga, H, Vintges, M, and de Jong, G. Beyond Silence and Rumor. Health Educ (2010) 110(5):382–98. doi:10.1108/09654281011068531

23. Rand, JR. Inuit Women's Stories of Strength: Informing Inuit Community-Based HIV and STI Prevention and Sexual Health Promotion Programming. Int J Circumpolar Health (2016) 75(1):32135. doi:10.3402/ijch.v75.32135

24. Joshi, A. Multiple Sexual Partners: Perceptions of Young Men in Uganda. J Health Org Mgt (2010) 24(5):520–7. doi:10.1108/14777261011070547

25. Treffry-Goatley, A, Lessells, R, Sykes, P, Bärnighausen, T, De Oliveira, T, and Moletsane, R. Understanding Specific Contexts of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence in Rural South Africa: A Thematic Analysis of Digital Stories from a Community with High HIV Prevalence. PLoS ONE (2016) 11(2):e0148801–19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148801

26. Ory, M, Lee Smith, M, and Mier, NWM. The Science of Sustaining Health Behavior Change: the Health Maintenance Consortium. Am J Health Behav (2010) 34(6):647–59. doi:10.5993/ajhb.34.6.2

27. Hancox, D. Stories with Impact: The Potential of Storytelling to Contribute to Cultural Research and Social Inclusion. M/C J (2011) 14(6). doi:10.5204/mcj.439

28. Wilson, M. “Another Fine Mess”: The Condition of Storytelling in the Digital Age. Narrative Cult (2014) 1(2):1. doi:10.13110/narrcult.1.2.0125

29. Dickson, D. The Case for a ‘deficit Model’ of Science Communication. London, United Kingdom: Science and Development Network (2005).

Keywords: Public Health, intervention, HIV, storytelling, insight, methodological tool, review

Citation: McCall B, Shallcross L, Wilson M, Fuller C and Hayward A (2021) Storytelling as a Research Tool Used to Explore Insights and as an Intervention in Public Health: A Systematic Narrative Review. Int J Public Health 66:1604262. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604262

Received: 26 May 2021; Accepted: 05 October 2021;

Published: 02 November 2021.

Edited by:

Erica Di Ruggiero, University of Toronto, CanadaReviewed by:

Sandra Ribeiro, Instituto Superior de Contabilidade e Administracao do Porto, PortugalCopyright © 2021 McCall, Shallcross, Wilson, Fuller and Hayward. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Becky McCall, YmVja3kubWNjYWxsLjE4QHVjbC5hYy51aw==

Becky McCall

Becky McCall Laura Shallcross1

Laura Shallcross1